Introduction1

This report is the third in a series investigating the extent of restrictive and exclusionary zoning across the state of California. The first report in this series covered the San Francisco Bay Area. Our initial research on the SF Bay Area examined the extent of restrictive zoning primarily in relation to the problem of endemic racial residential segregation. This research spurred a follow-up report which became the first of our zoning series to probe this problem more deeply, examining the relationship between restrictive zoning and community characteristics and resources, educational outcomes, economic mobility, environmental conditions and much more.

The second report in this series focused on the Greater Los Angeles region, also known as the SCAG region, by its metropolitan planning area organization acronym. In that report, we examined the extent of single-family zoning in the region, the relationship between such zoning and racial composition, and the characteristics of communities based on their degree of single-family-only zoning. As with the Bay Area, we found striking and disturbing patterns of racial and economic exclusion associated with communities with a greater-than-usual degree of single-family-only zoning. Supplemental research also found significant disparities in revenue and expenditure across the Los Angeles region in relation to the degree of single-family-only zoning.

Both regional analyses were based on a careful collection and reporting of municipal zoning maps, knitting together into regional maps. The analyses of both regions found profound and disturbing correlations between the observed extent of single-family-only zoning and racial demographics, segregation, rents, home values, and much more. For instance, in both regions, the degree of single-family-only zoning is inversely correlated with the proportion of Latino residents and lower-income residents, and strongly correlated with rents, property values, and incomes.

This third report continues that research, but with a focus on the greater Sacramento region. The Sacramento region (also known as SACOG) covers six counties featuring 22 municipalities,2 including the seat of California’s state government, Sacramento. This region includes nearly 2.5 million people who reside in diverse areas including the urban hub of Sacramento and extensive agricultural districts,3 as well as smaller jurisdictions stretching into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Increasingly, the Sacramento region faces pressure from a growing population as rising housing costs in the nearby Bay Area and the city of Sacramento itself force residents to more affordable suburbs.

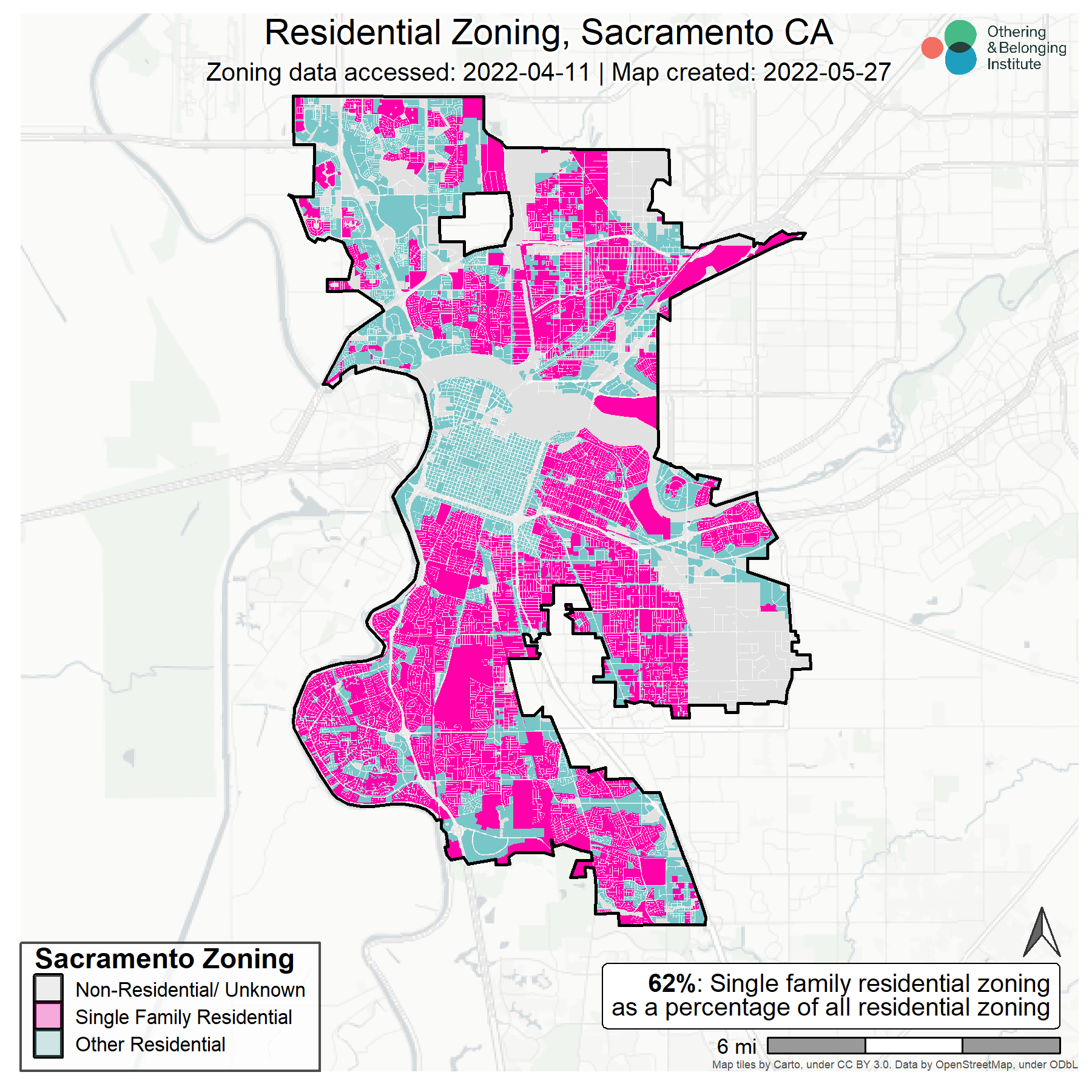

Accompanying this report is a repository of 28 static zoning maps for the SACOG region, one map for each municipality with zoning ordinances in the region, one for each of the six counties, and one for the region as a whole. We have also created an interactive map with a drop-down menu containing each municipality. Each map illustrates the extent of single-family-only residential zoning, multi-family and mixed-use residential zoning, and non-residential zoning by area. It also indicates the percentage of single-family zoning relative to all residentially zoned areas, as well as the date in which the underlying zoning ordinance was accessed and the date the map was created. See Figure 1 below, as an example, of the city of Sacramento.

This report follows an identical methodology to that of the Greater LA report. Rather than reiterate the numerous challenges to creating zoning maps and our methodological approach, we direct your attention to the appendix to this report, where we summarize both. Additionally, all the parcel-level data for each city is shared via a Github repository which includes the original zoning code as well as OBI’s simplified zoning categories for review and analysis.

An Overview of Single-Family Zoning in the Sacramento Region

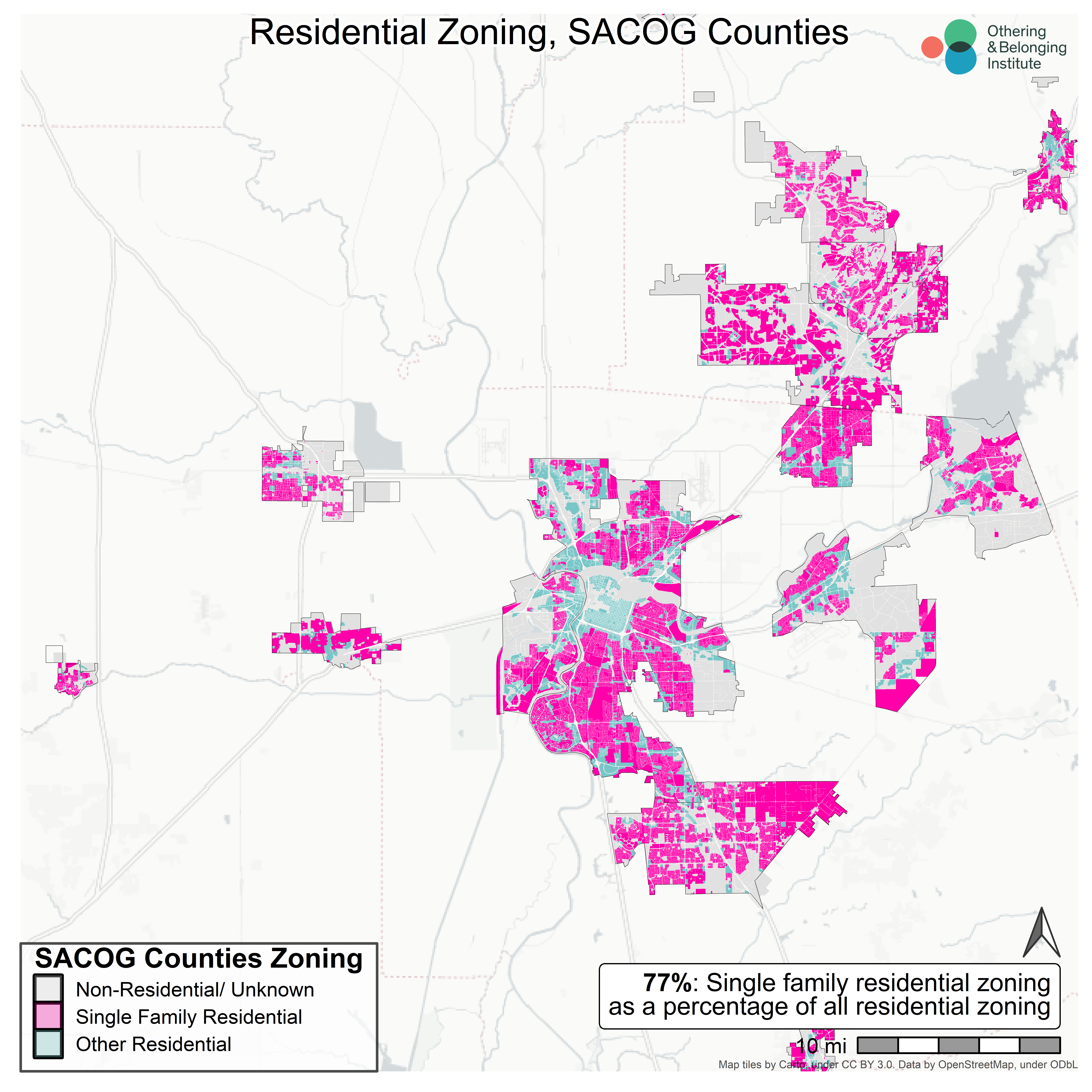

Consistent with the findings of our prior two regional investigations, we find that single-family-only zoning is a predominant form of zoning within the Sacramento region, especially within residential areas. Specifically, we find that 77.10 percent of residential land in the region is exclusively reserved for single-family housing (See Figure 2 below). From a cross-sectional view of local jurisdictions rather than a regional view, we find that, on average, about 81.1 percent of residential land is restricted to single-family homes only, with a median of about 81.2 percent.4 The average amount of total land (including commercial areas and parks) exclusively reserved for single-family housing was 42 percent. In contrast, we also find that only 10.7 percent of total land, and 19.9 percent of residential land, is available for multi-family developments. Zoning ordinances throughout the Sacramento region are exceptionally hostile to density.

These findings are squarely in line with the findings or our previous reports. Our initial analysis of the San Francisco Bay Area (consisting of 101 jurisdictions) found that 82 percent of all residential land was zoned for single-family-only dwellings. When we extended our analysis to include jurisdictions with fewer than 10,000 people, that figure rose to 85 percent. That analysis found that the average amount of residential land in each city is 81 percent, with a median of 86 percent. Although the Bay Area has more single-family zoning than the SCAG region, it has more residentially-zoned land as well.

Our research on the Greater LA region (which includes 191 jurisdictions) found that 78 percent of all residential land was reserved exclusively for single-family homes by zoning designation in that region. All of these findings are also consistent with investigations conducted in other regions of the country. For instance, a report by the Twin Cities’ Star Tribune found that 73 percent of residential land in the Twin Cities (104 jurisdictions) is governed by local zoning ordinances that only allow single-family detached homes.5 Similarly, a statewide analysis of Connecticut (including over 2,600 jurisdictions) found that 70 percent of residential land was zoned exclusively for single-family dwellings.6

As various regional analyses continue to be produced, it appears that the percentage of single-family-only zoned areas of residential land continues to fall within a remarkably consistent range. The SACOG region falls more toward the upper end of that range, but is strikingly similar to our findings in the greater LA region, despite a vastly different context in terms of population, regional sizes, and number of jurisdictions included.

Table 1 below presents each jurisdiction in the SACOG region by its percentage of single-family-only zoning, broken into three categories: Low to Moderate (0-77.4 percent); High (77.4-89.5 percent); and Very High (89.5-100 percent).7 We will use that delineation for our analysis in the next two sections of this report.

Table 1: Degree of Restrictive Zoning by Jurisdiction

|

Low to Moderate (0-77.4%) |

High (77.4% - 89.5%) |

Very High (89.5% - 100%) |

|

Citrus Heights |

Auburn |

Elk Grove |

|

Galt |

Colfax |

Lincoln |

|

Live Oak |

Davis |

Loomis |

|

Marysville |

Folsom |

Placerville |

|

Sacramento |

Rancho Cordova |

Rocklin |

|

West Sacramento |

Roseville |

Wheatland |

|

Woodland |

Yuba City |

Winters |

Single-Family Zoning and Race

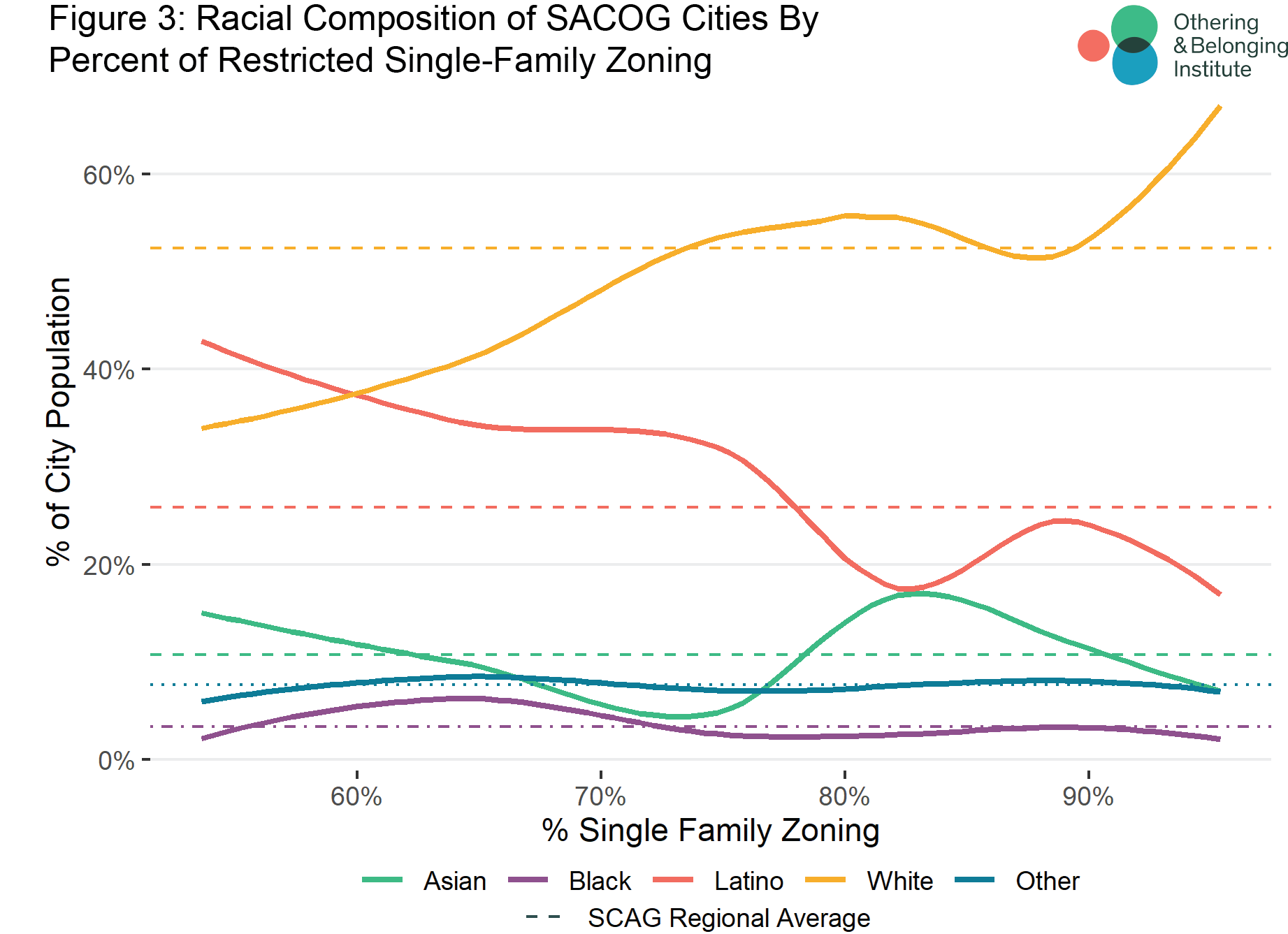

In this section of our report, we present findings regarding the observed relationship between single-family zoning and race, including racial demographics and levels of racial residential segregation, for the SACOG region. Consistent with our prior work, we find a striking relationship between jurisdictions with an extremely high degree of single-family-only zoned residential areas and the racial composition of those communities. Figure 3 below shows the percentage of each racial group represented in each community based on the percentage of single-family-only zoning as a portion of residential land along with a dashed line to show the SACOG regional average for all cities.

What Figure 3 specifically illustrates is that Latinos are most heavily represented in jurisdictions with the smallest percentage of single-family-only zoning, and decline sharply as the percentage of single-family-only zoning exceeds 75 percent of all residential land. Conversely, the percentage of white residents per jurisdiction rises steadily (with the exception of a small downturn in the 80-90 percent range) as the percentage of single-family-only zoning increases, and rises sharply as the percentage of single-family-only zoned residential land exceeds the upper eighties.

This pattern confirms that, for the SACOG region, single-family-only zoning has a racially exclusionary appearance: the more single-family-only zoning, the whiter the jurisdiction and the proportion of Latinos declines relative to the regional population.

It should be noted, however, that the percentage of Black residents does not appear to follow as stark a pattern as was observed in the San Francisco Bay Area, although there is a noticeable decline. Another notable difference from our Bay Area report is that the proportion of Asian residents rises even more sharply in the middle of the range as the percentage of single-family-only zoning increases than that of white residents, although it then declines as the percentage of single-family zoning increases beyond that range.

Table 2 below indicates the racial breakdown and level of segregation according to three groupings of jurisdictions by their extent of single-family-only zoning.

Table 2: Single-Family Zoning and Racial Composition and Segregation

| Low to Moderate SFZ | High SFZ | Very High SFZ | All Zoning | |

| % Asian | 9.33% | 15.10% | 8.45% | 10.76% |

| % Black | 4.31% | 3.41% | 2.35% | 3.35% |

| % Hispanic | 35.29% | 18.68% | 22.45% | 25.82% |

| % White | 43.55% | 54.97% | 59.12% | 52.43% |

| % Other | 7.51% | 7.83% | 7.62% | 7.65% |

| Population | 775,455 | 465,791 | 319,040 | 1,560286 |

| Within City Segregation | 0.036 | 0.049 | 0.039 | 0.041 |

| Divergence from Metro | 0.097 | 0.083 | 0.155 | 0.106 |

| Number of Municipalities | 7 | 7 | 7 | 21 |

This table, perhaps even more clearly, illustrates the relationship between the extent of single-family-only zoning and racial composition. The highest percentage of Latino and Black residents is found in the category with the smallest extent of such zoning. Conversely, the highest percentage of white population is in the category with the greatest extent of such zoning.

Additionally, this chart shows that cities with a low-to-moderate or very high percentage of single-family-only zoning diverge more from the region as a whole in terms of their racial proportions, suggesting a higher degree of inter-municipal racial residential segregation in these communities.8

Single-Family Zoning and Other Community Characteristics

In this section, we present a number of important findings regarding the characteristics of jurisdictions, including household income,9 home value,10 educational attainment,11 educational performance,12 and environmental health13 in relation to their percentage of single-family-only zoned areas.

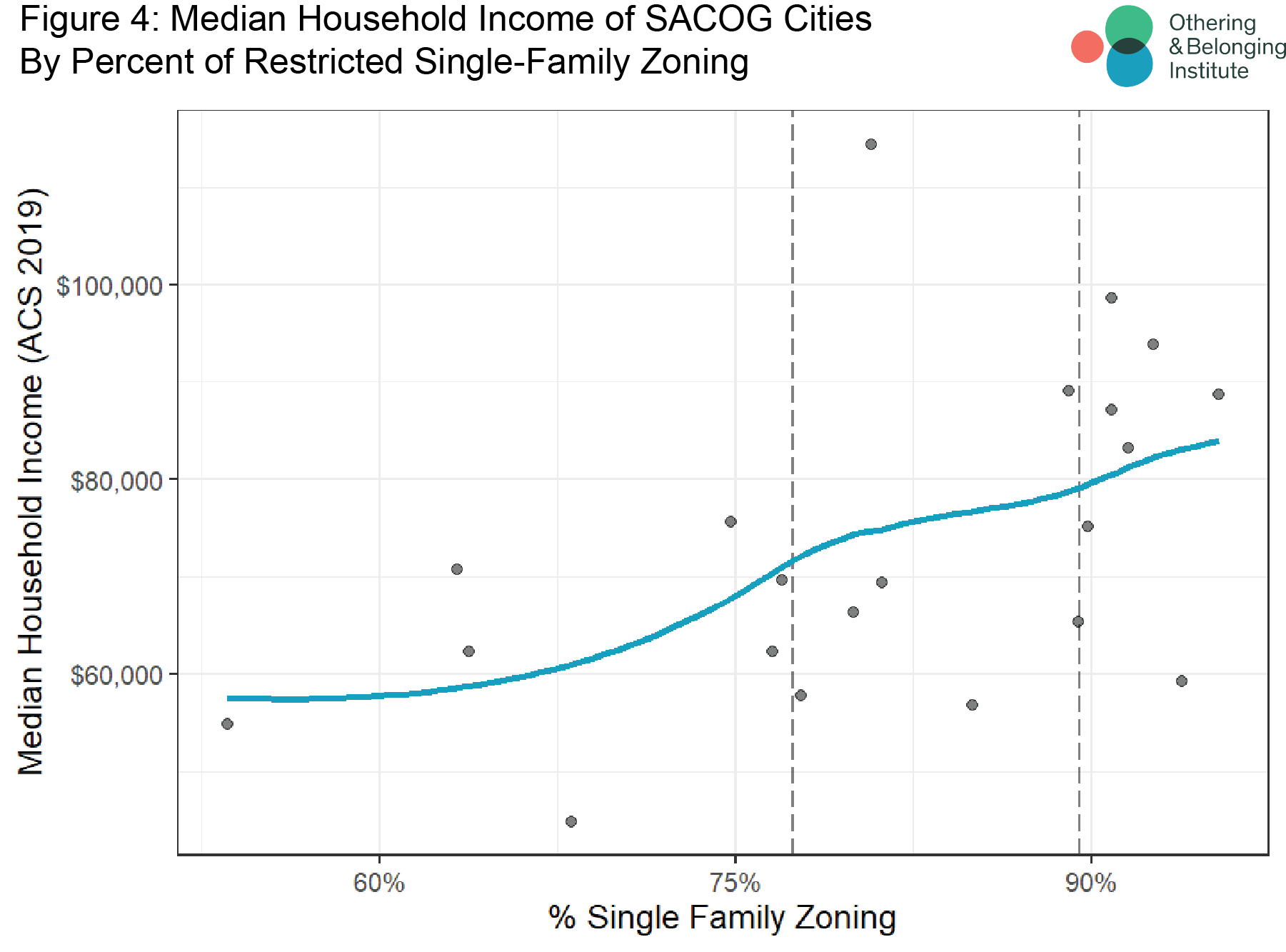

Single-Family Zoning and Household Income

First, we find a direct relationship (a positive correlation) between median household income and the percentage of single-family-only zoning by jurisdiction.14 Household incomes increase as the percentage of single-family-only zoning rises. We interpret this pattern to support the supposition that this type of zoning has an economically exclusionary effect, making residential property more expensive so that lower-income people are unable to afford to live in such jurisdictions. Figure 4, below, illustrates this relationship.

Each dot represents a municipality in the SACOG region. The blue line represents the line of best fit, meaning the line that best expresses the relationship between the two variables, here determined using local polynomial regression. Specifically, we find that incomes are $62,884 on average in the lowest category, $74,148 in the middle category, and $83,658 on average in the highest category.

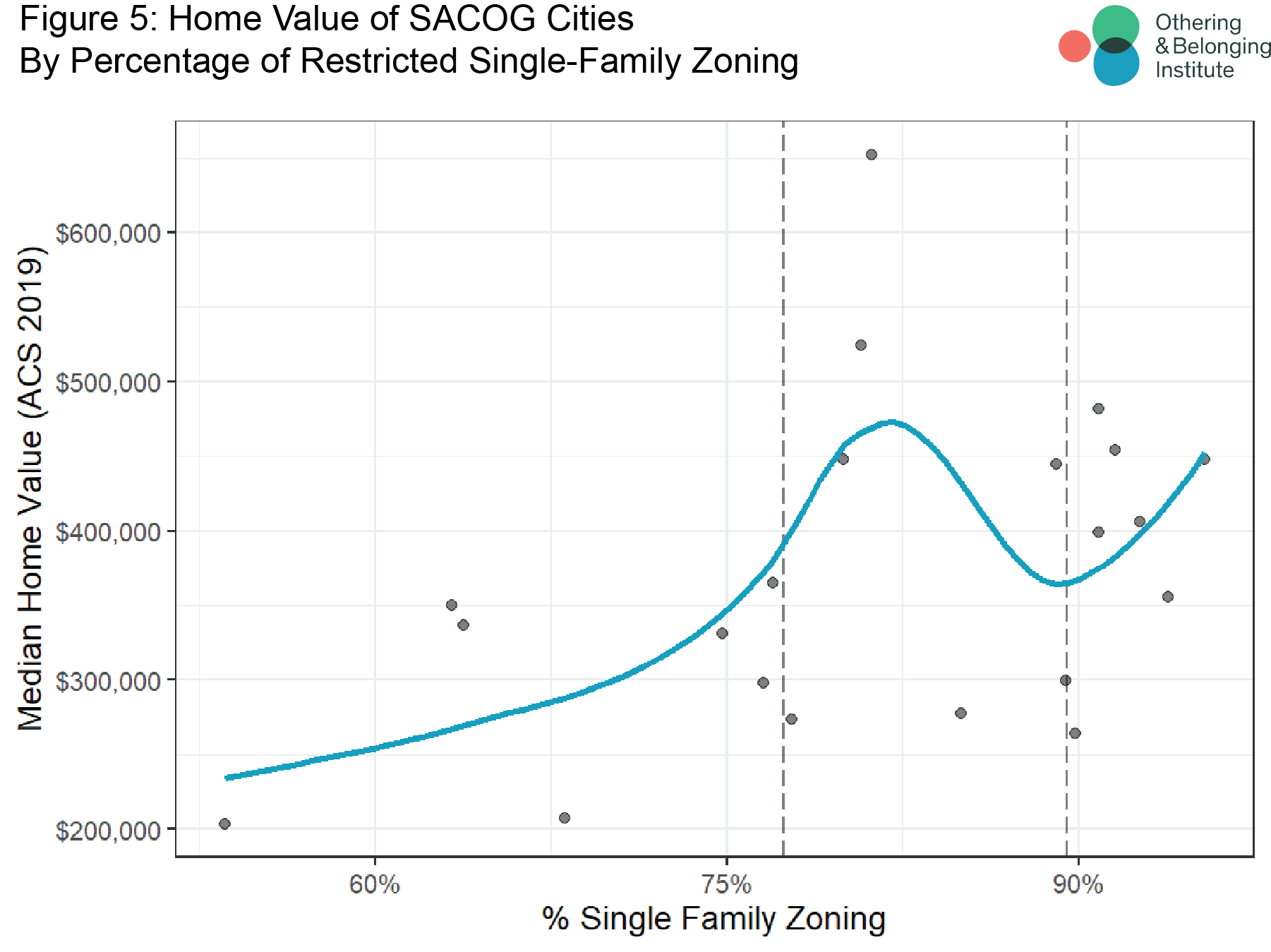

Single-Family Zoning and Home Values

Second, we find a similar relationship between the percentage of single-family-only zoned areas per jurisdiction and median home values. Figure 5 below illustrates this dynamic. Even more than the relationship between zoning and household income, this relationship suggests that restrictive zoning plays a role in making housing more expensive.15

The relationship here is clear, although not quite as stark as our previous reports. We find that median home value generally increases as the percentage of single-family zoning increases in a municipality. An exception to this trend is present in the middle category, which is likely driven by the unique circumstances of the city of Davis, the data point with the highest median home value. Davis is home to the only University of California campus in the SACOG region. Housing development in Davis is limited by extensive floodplains that surround three sides of the city.16 This keeps housing supply low, although demand for housing in Davis is high due to the student population and the perceived desirability of the town. Because there are fewer jurisdictions in the region, Davis plays an outsized role in shaping the overall pattern.

Overall, the average median home value of the Very High category ($401,257) is more than 30 percent greater than that of the Low to Moderate category ($298,729).

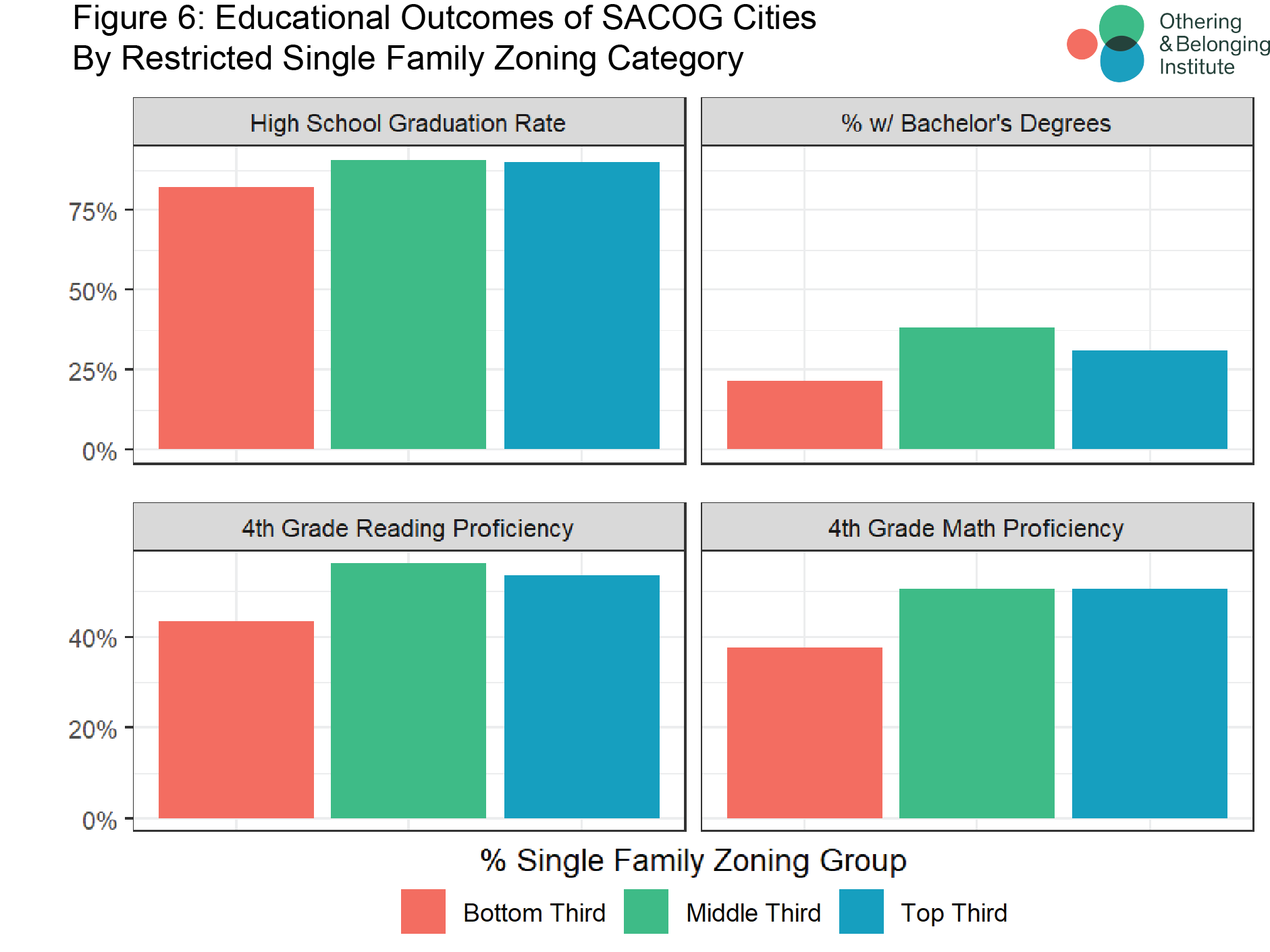

Single-Family Zoning and Educational Outcomes

In the San Francisco Bay Area, we found that single-family zoning appeared to contribute to the sorting of people by educational attainment, which helps explain the sorting by income and wealth (as measured by housing prices) as well. The impact of single-family zoning on educational outcomes is less clear in the SACOG region. Figure 6, below, shows the relationship between the percentage of single-family-only zoning and high school graduation rates, test scores, and the percentage of residents with a college degree.

Municipalities with the least single-family zoning scored the lowest across all four of these educational outcomes, consistent with our findings for the Bay Area and Greater LA. However, the middle category of municipalities are the top performers in all four categories, particularly in the percentage of residents who attain bachelor’s degrees. This result is likely due to the influence of Davis and Folsom, which have the highest (73 percent in Davis) and second highest (51 percent in Folsom) percentage of adults over the age of 25 with bachelor's degrees. For Davis, it is likely that this high educational attainment is related to the presence of the UC. As for Folsom, the multinational computing and technology company Intel employs 17 percent of the entire city’s workforce.17 This may attract highly educated individuals to the city. When these analyses are run without Davis and Folsom, the trend of improved educational outcomes with greater percentage single-family zoning in a city re-appears across all four outcomes.18

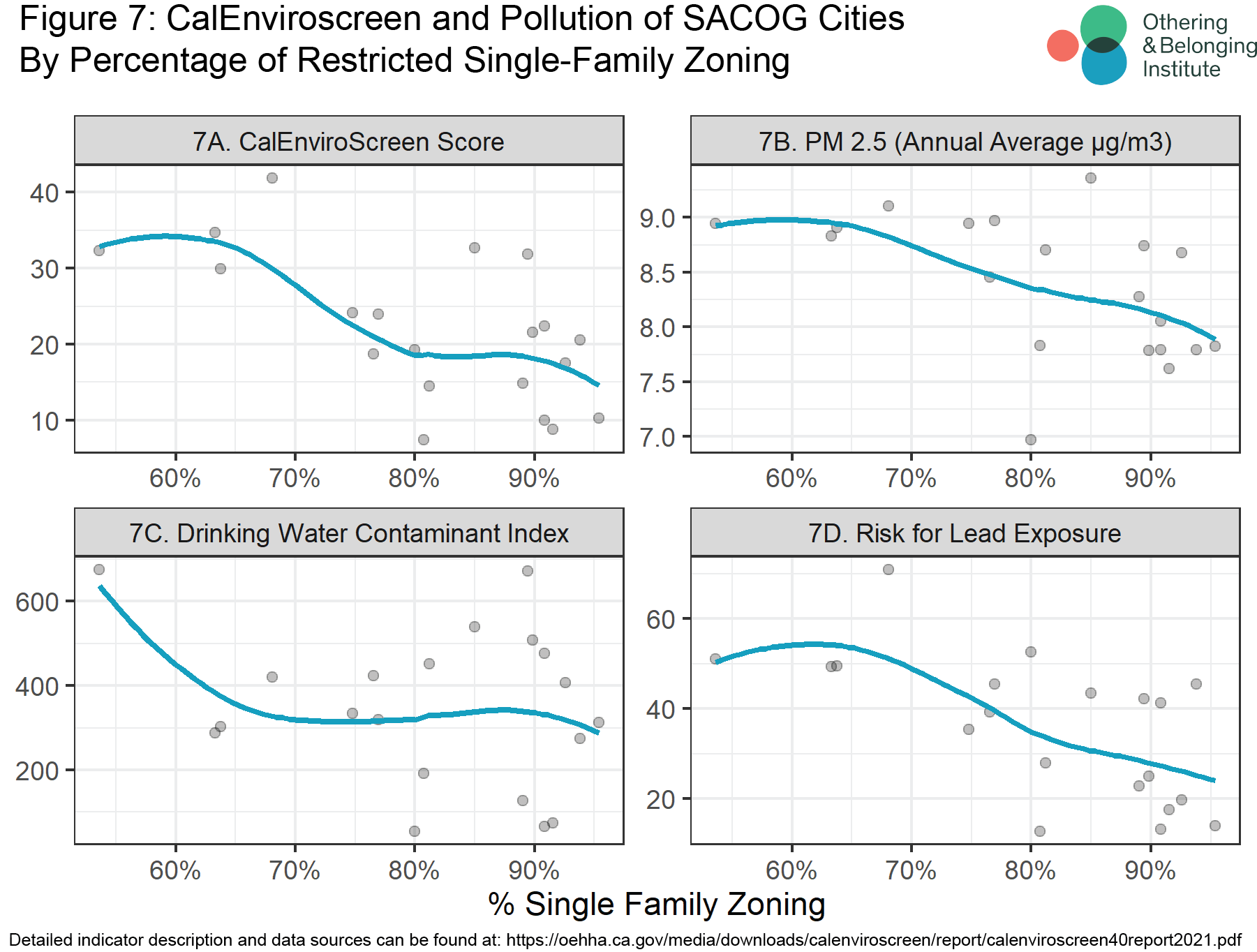

Single-Family Zoning and Environmental Health

Zoning does not just contribute to the sorting of people by class, educational attainment and race, it also appears to shape the quality of the environment. To the extent that zoning is used to hoard or channel resources, it makes sense that environmental conditions would vary with the extent of single-family-only zoning and other restrictive land use regulations.

CalEnviroScreen is a mapping tool that “helps identify California communities that are most affected by many sources of pollution, and where people are often especially vulnerable to pollution’s effects.”19 Figure 7, below, uses indicators from CalEnviroScreen 4.0 (as well as the instrument itself) to show how certain environmental conditions change as the degree of single-family zoning changes.20

As shown in Figure 7A, the vulnerability observed by CalEnviroScreen drops by more than 50 percent in the cities with the highest percentage of single-family zoning, compared to those with the least percentage of single-family zoning. Meanwhile, Figure 7B demonstrates that particulate matter PM 2.5 (a known contributor to asthma) declines as the percentage of single-family-only zoning increases, though the decrease is less dramatic than that of the overall CalEnviroScreen score.

The quality of drinking water (displayed in Figure 7C) follows a similar pattern, except that the decrease levels off at approximately 70 percent single-family zoning. Given the high number of suburban and exurban areas in this analysis, and the prevalence of agriculture in the SACOG region, many of these municipalities may be impacted by fertilizer run-off and other pollutants present in such areas.21 This could explain the similarity in drinking water quality among the SACOG municipalities.

Finally, it is extremely alarming to discover a linear inverse relationship between the levels of lead, a known neuro-toxin,22 and percentage of single-family zoning, as shown in Figure 7D.

Single-Family Zoning and Economic Mobility (Opportunity)

The foregoing analysis examined the relationship between the degree of restrictive zoning and certain community characteristics. This analysis supports the theory that restrictive zoning is used to hoard opportunity and exclude people on the basis of race and class. Perhaps more revealing in this regard are the outcomes for children raised in different environments based on the degree of single-family zoning present.23

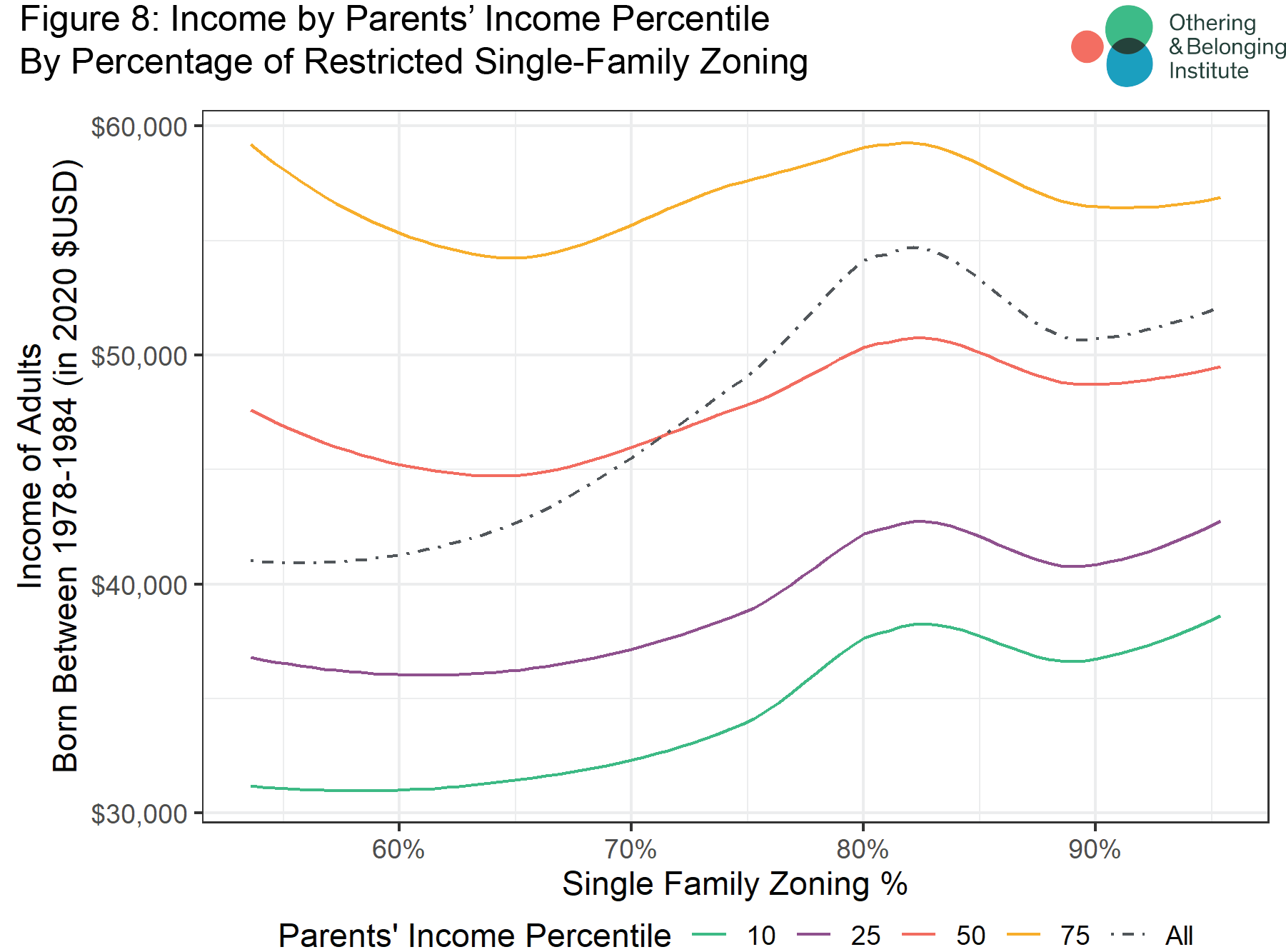

The Opportunity Atlas contains information on childhood outcomes for nearly every American child born between 1978 and 1984.24 Examining tracts in the SACOG region, we are able to see a clear and consistent correlation between single-family zoning and positive outcomes for children across income distribution born in this time frame. Figure 8 below shows that, for these children, there is a direct relationship between the degree of restrictive zoning in their environment and their ultimate income level as an adult. We theorize that this is explained by the degree to which zoning controls communal resources for human capital investment and development.

It appears that for children with parents in the 10th and 25th income percentiles, those who are raised in environments with a higher percentage of single-family zoning appear to have higher annual incomes as adults. This trend is most pronounced when looking at the outcomes for all children cumulatively, although the relationship is tempered as the percentile income of the child’s parents’ increases. Parental income percentile also seems to play a large role in the child's income as an adult.

For example, Figure 8 shows that overall, children born into families who reside in communities with 95 percent single-family-only zoning make approximately $10,000 more per year as adults than children born into families living in areas with less than 60 percent single-family-only zoned residential areas.

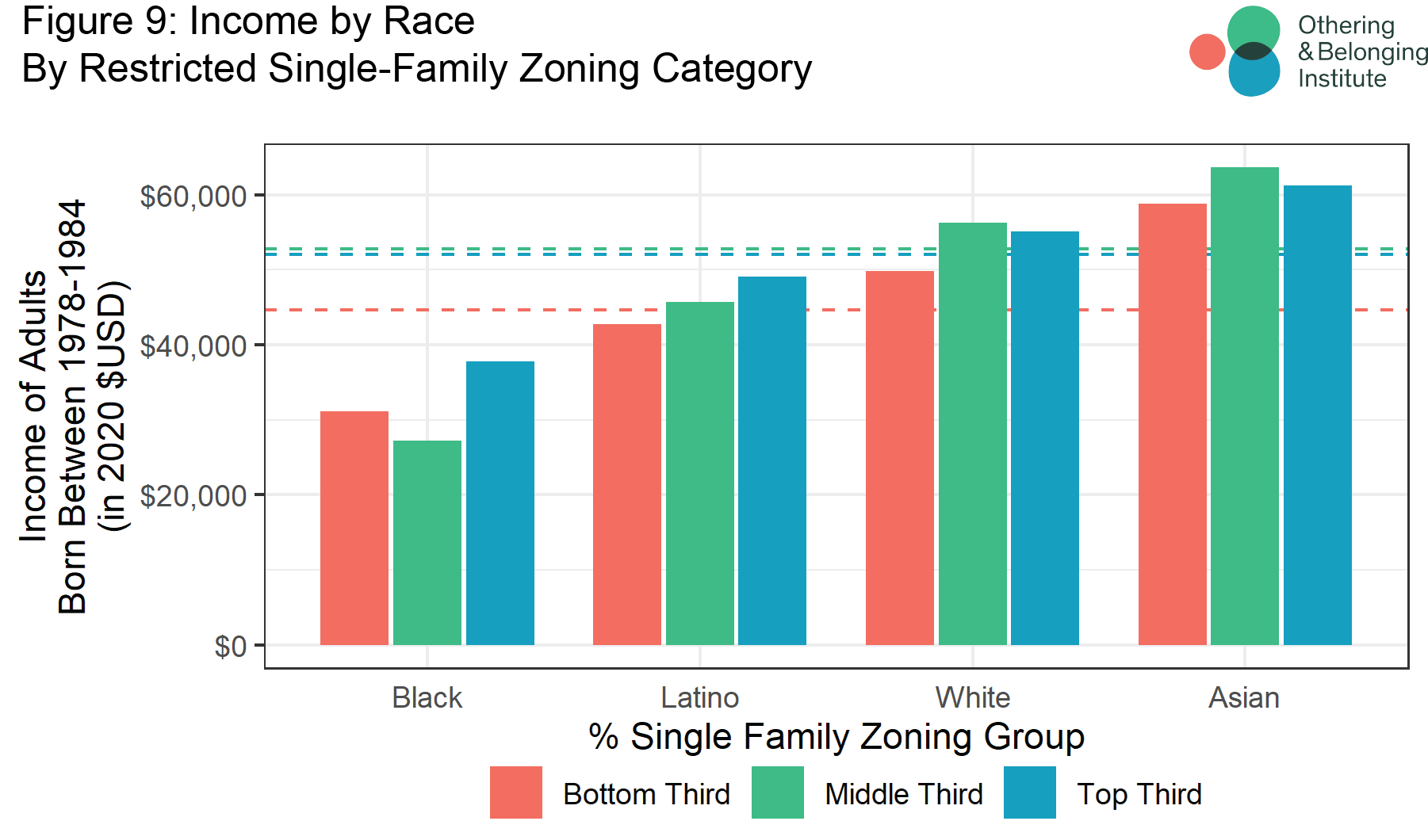

This relationship holds true for some racial groups, specifically among Latinos, as shown in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9 shows the adult annual incomes for children raised in the SACOG region based on the percentage of single-family-only zoning, broken down by race. For all racial groups, individuals raised in jurisdictions with the highest levels of single-family-only zoning out-earn those raised in jurisdictions with the least percentage of such zoning.

It is interesting that White and Asian individuals raised in municipalities with middling levels of single-family-only zoning appear to earn more in adulthood than their counterparts in the top third of jurisdictions, while this does not hold true for other racial groups, a pattern which may be due once again to the influence of Davis and Folsom. Without those cities, increasing levels of single-family zoning correlates with increased income in adulthood for White and Asian children.

Identifying Cities for Reform

As in our previous two regional reports, we attempt to identify cities that may be the stronger candidates for zoning reform. Borrowing the methodology we used in the Los Angeles report, we use four factors to pinpoint such jurisdictions:

1) The percentage of single-family-only zoned residential areas

This indicator selects only jurisdictions with a high or extremely high level of single-family-only zoned areas.

2) The percentage of the jurisdiction that is designated as “high opportunity” on the state’s COG-based opportunity maps25

The Tax Credit Allocation Committee’s official opportunity maps already guide the state’s allocation of federal subsidies for affordable housing, and for that reason are useful indicators for identifying jurisdictions with a high degree of opportunity. Jurisdictions with a greater share of high-opportunity neighborhoods are better targets for reform in relation to equity objectives. Here, we chose municipalities with 85 percent or more neighborhoods designated high-opportunity areas.

3) Distance from regional economic centers (central business districts)

This indicator is a proxy for access to jobs. Upzoning areas that are remote or difficult to access makes far less sense than upzoning neighborhoods that are already accessible and proximate to jobs and businesses. Therefore, we excluded jurisdictions too remote from job centers as places to prioritize reform. We selected municipalities where the commute is 40 minutes or less from the nearest central business district. There are other possibly more direct measures of job proximity, but this measure has the additional benefit of reflecting significant existing transit infrastructure. Central business districts are accustomed to accommodating large numbers of daytime workers. We apply this criteria both in terms of distance and travel time.

4) Poor performance with RHNA targets

The Regional Housing Needs Assessment requires that every jurisdiction in the state plan for housing at five different income levels, "very-low," "low," "moderate," "above-moderate," and “high.”26 Jurisdictions are required to zone for local needs, but in practice, jurisdictions do not meet their RHNA requirements.27 Jurisdictions that perform especially poorly with respect to RHNA targets for low and very-low income housing are excellent candidates for zoning reform because government agencies have already determined that they should shoulder a greater share of affordable housing developments. Table 3 below displays our results.

Table 3: Candidates for Zoning Reform and Selection Indicators

| Cities | Single Family % | % of Neighborhoods in High Opportunity Category | RHNA Low & Very Low Income Completion28 | Minutes from CBD | Miles from CBD29 |

| Elk Grove | 93% | 85% | 5% | 20 | 12.7 |

| Loomis | 92% | 100% | 0% | 30 | 22.5 |

| Rocklin | 91% | 85% | 0% | 32 | 20.5 |

| Folsom | 81% | 94% | 0% | 32 | 19.8 |

In summary, we conclude that Elk Grove, Loomis, Rocklin, and Folsom are the four jurisdictions that appear to be most urgently in need of zoning reform based on our four factor criteria. This does not mean that other jurisdictions should not also consider it. But these four jurisdictions are the most extreme cases within the region.

Conclusion

As with the San Francisco Bay Area and the greater Los Angeles regions, Sacramento’s residential areas are dominated by single-family-only zoning, stifling the development of denser housing options, perpetuating racial and economic segregation, and shaping communities and the distribution of opportunity for millions of Californians.

We hope this report sheds critical light on the pattern and extent of the problem in this region. We will continue our investigation of other regions as we build toward a statewide zoning atlas over the next year.

APPENDIX: CHALLENGES & METHODOLOGY

Challenges

There are many daunting research challenges to studying municipal zoning. Foremost among them is the lack of consistent classifications or base formulae for zoning designations from which they may be derived. Zoning codes are generally dense, technical, and difficult to access. While there may be strong similarities in zoning taxonomies across jurisdictions with land use authorities, the particulars of each zoning code are often idiosyncratic to the jurisdiction. Certain designations may mean different things in different jurisdictions. This means that studying regional zoning patterns requires tedious and time-intensive effort to produce accurate data.

There are shortcuts researchers can use to gather data, but they lack precision. The most common and widely relied upon shortcut is the use of survey instruments (e.g. the Wharton Regulatory Land Use Index). We summarized notable zoning surveys, going back to the 1970s, and their respective strengths and limitations, in our Bay Area report.30 Although there are a number of other proposed methodological shortcuts, including restricting analysis to a sample of cities using American Community Survey samplings of housing units within cities, or drawing inferences about zoned density from property tax records, the vast majority of research conducted on this issue relies upon these survey instruments.31

While these surveys may be generally useful, there is evidence to suggest that their results contain systematic errors, partly due to the inaccurate perception of the survey respondents.32 These surveys also suffer from lack of reliability, since, in many cases, respondents fail to complete the survey, creating holes in the datasets.33 These instruments are also limited and tend to focus on the largest jurisdictions, meaning that smaller municipalities are less likely to be included. This may be another source of systematic bias in such data, since smaller municipalities may have a greater share of restrictive zoning.

Another challenge to studying zoning is that zoning ordinances and codes do not necessarily indicate actual zoning, especially for planned developments. Planned development is typically a designation that allows for more flexible or dynamic zoning and land use, where planners anticipate or intend future development. The intended use for such parcels may not be defined in the municipal zoning code, meaning that it has to be observed directly.34

A related problem is that zoning codes do not always reflect the built environment, and vice versa. This is probably the single biggest source of confusion regarding our zoning maps, as evidenced from inquiries we have received about them. Our maps and analyses are of zoning, not the built environment. While the actual built environment may be the most relevant piece of information for some purposes (such as researchers or policymakers who are primarily concerned with the production of housing), our research is focused on better understanding how zoning designations themselves shape or correlate with certain community characteristics and life outcomes.

So-called “non-conforming uses,” which create a divergence between the built environment and zoning laws, exist for many reasons. Some developments, especially older ones, may have been constructed before zoning codes were adopted or prior to a down-zoning of the neighborhood to prevent new, higher density developments. Developers of more recent developments may petition for, and receive, a “spot variance,” which is permission to build at a higher density or taller than what is permitted by ordinance. Certain state laws, like density bonus laws, may similarly create override mechanisms that generate non-conforming structures. One cannot easily scan an environment and accurately infer a zoning designation.

Methodology

Because we are specifically interested in the effects and/or correlates of restrictive zoning itself, and most of the zoning codes were idiosyncratic across municipalities, for purposes of this report, we simplified zoning designations into three broad categories: Single Family Residential, Other Residential, and Non-Residential/Unknown, defined as follows:

-

Single Family Residential is land designated for detached, single-family residential land use (one or two dwelling units per parcel of land) in both low and high density. This includes single-family homes and two-family detached dwellings, and usually includes single-family zones, low-density zones, agriculture zones (if single-family homes are permitted) or estate zones. The zone is not classified as single-family residential if it only permits the following: caretaker’s residence, employee housing, or live-work units

-

Other Residential includes both multi-family residential and mixed-use residential.

-

Multi-family residential is land designated to allow for multiple dwelling units per parcel of land. This includes apartment buildings, duplexes, triplex, fourplex, townhouses, condos, mobile home parks, and two-family attached dwellings. Additionally, if a zone’s intent allows for both single-family homes and any of the multi-family housing above, it is sorted into the multi-family category. This category does not include employee housing and student housing.

-

Mixed-Use Residential is land designated to blend multiple uses that includes residential use. This includes mixed-use commercial zones permitting residential use, zones allowing multi-family buildings with commercial spaces (e.g., on the group floor), and zones where residential use and other non-residential uses such as commercial or industrial uses are both permitted.35

-

-

Non-Residential is land that is designated for non-residential uses. This includes parks and open space, commercial, industrial, and public land. Non-developable land was removed from the overall land area, including water, waterways, marshland, and highways or streets.

Municipal zoning code documents are the primary source to identify each zoning category for each city, describe the purpose of each, and list what is permitted to be built in each of these zones. We utilized these documents for each city to recode each zone into the typology listed above. Based on city ordinances for each unique zone in each municipality, we recorded the type of housing development permitted and conditionally permitted as follows:

P: permitted as right. We did not include building types that were permitted for accessory use only.

C: conditionally permitted; requires review; requires minor use permit

We prioritized and focused on the intent and the purpose of the zone to sort the zones into one of the three categories: non-residential/unknown, single-family, and other residential. For example, a residential zone intended for both single-family and multi-family developments would be classified in the other residential category (which includes multi-family zones), even if multi-family is only conditionally permitted. This is because the zone’s intention was for both single-family and multi-family developments.

When the intent and purpose of the zone was unclear, we classified the zone based on what is permitted in the zone. For example, consider a “general residential” zone that does not specify whether it is strictly for single-family homes in its intent. If it permits single-family homes but only conditionally permits multi-family homes, it would be classified in the single-family category. And if it permits both single-family homes and multi-family homes, it would be classified in the other residential category. Since we prioritized the zone’s stated intent and purpose in the city ordinance, we would only rely on the permitted use if the intent and purpose was unclear.

For planned development and specific plan zones where the municipal ordinance does not detail the intent and purpose sufficiently for us to classify the entire zone or zones that are missing in the municipal ordinance, we used the standardized land use class from SACOG to categorize the parcels in these zones into one of the three categories above.

We accessed parcel-level zoning data primarily from shapefile repositories maintained by individual municipalities, in addition to the repositories maintained by the SACOG organization itself. We applied our classification of simplified zoning categories to the zones found in the zoning shapefile for each city. In the absence of a zoning shapefile for a particular city either from the SACOG repository or the city planning/GIS department, we searched for these shapefiles from ESRI’s ArcGIS Hub and other online sources.36

Once we obtained the zoning shapefile, we created a list of all zoning codes available within the shapefile. We used the description of each zone in the municipal code document, and re-coded each of those to one of the three categories listed above. We then applied our simplified typology to each of the parcels in the shapefile. We mapped the data to display this typology.

We realize that our simplified taxonomy of myriad zoning designations into three categories (in order to draw out the degree to which single-family-only zoning predominates residential areas) conceals many other aspects of zoning codes that impede or restrict development or certain types of developments. For example, height limitations, setback requirements, discretionary reviews, parking requirements and the like can all inhibit density, even in multi-family residential or mixed-use zones. For that reason, in constructing this tranche of maps, we have separately created a database of additional zoning characteristics for each jurisdiction, which we will release at a future point in completing a statewide “zoning atlas” for California.37 Until then, our focus is on single-family-only residential zoning as the principal form of restrictive and exclusionary zoning.

Additional notes on methodology are below.

Data procurement: Zoning shapefiles for each city in the region were gathered from multiple sources, including the SACOG public data hub, city and county planning/GIS or relevant departments, and ESRI’s ArcGIS Hub in the listed order to ensure we have the most updated shapefiles to conduct our analysis.

Quality check procedures: Human errors could impact the quality of the analysis so it was important to establish data quality checking protocols to reduce any human errors. We followed these procedures at different stages of data collection and classifying our zoning categories:

We checked for updated zoning shapefiles from individual city planning departments for each municipality to ensure we procured the most updated version of each shapefile. Once the zoning codes were extracted from the shapefiles and were re-coded to our three simplified zoning categories, another team member conducted a spot check to ensure the extraction and coding was done properly and with internal consistency. We cross-checked our final maps against the zoning maps provided by the city to ensure our processing was accurate.

Though attempts were made to minimize any human error while interpreting various zoning codes and recoding those to our simplified categories, it was beyond our capacity to check the input data for accuracy. We were not able to check that the zoning shapefiles supplied by SACOG or any city’s planning department had the data entered correctly. We solicit any inputs or suggestions from the general public or city departments to highlight any inconsistencies in identifying the correct zoning categories and/or share updated zoning data to ensure our mapping and analysis are accurate.

- 1 The authors would like to thank Othering and Belonging Institute graduate student researcher Shahan Shahid Nawaz for his invaluable assistance in helping build the repository of municipal maps that made this analysis possible as well as for his insights and analysis, and Chih-Wei Hsu for his guidance on coding and analysis.

- 2One municipality, Isleton, had no zoning data available and consequently was not included in this report.

- 3American Community Survey: 2015-2019 5-Year Data (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020), https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html.

- 4By "cross-sectional" we mean that we averaged or identified the median from the sum of the individual jurisdictions rather than dividing the percentage of single-family-only zoned land out of the percentage of all residentially zoned land in the region as a whole.

- 5MaryJo Webster and Michael Corey, "How Twin Cities housing rules keep the metro segregated," Star Tribune, August 17, 2021, https://www.startribune.com/how-twin-cities-housing-rules-keep-the-metro-segregated/600081529/.

- 6Sara Bronin et al., “Connecticut Zoning Atlas," Desegregate Connecticut, https://www.desegregatect.org/atlas.

- 7Though we considered using Jenks natural breaks to divide the categories used in our analysis, we ultimately chose a division based on percentiles as described. Jenks natural breaks-based groups would have been as follows: 0-68% - low to moderate (32 municipalities), 68-81% - high (7 municipalities, 81-100% - very high (11 municipalities). Due to the highly uneven distribution of cities among these three groups, and the small number of municipalities in this analysis, we chose the percentile division.

- 8For a description of this measure of segregation, the formula and its utility, see Stephen Menendian, Samir Gambhir, and Arthur Gailes, "Technical Appendix," in The Roots of Structural Racism Project (Berkeley, CA: Othering & Belonging Institute, 2021), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/technical-appendix.

- 9“Selected Economic Characteristics,” American Community Survey, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html.

- 10“Selected Housing Characteristics,” American Community Survey.

- 11“Selected Social Characteristics,” American Community Survey.

- 12California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, English Language Arts/Literacy and Mathematics: 2018-2019 (Sacramento, CA: California Department of Education, n.d.), https://caaspp-elpac.cde.ca.gov/caaspp/ResearchFileListSB.

- 13CalEnviroScreen 4.0 (Sacramento, CA: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2021), https://calenviroscreen-oehha.hub.arcgis.com/.

- 14The correlation coefficient between percentage of single-family-only zoning and median household income for the city is 0.506. The blue line in Figures 4 and 5 represent a moving regression which fits local relationships between household income and home value to the single-family portion of the residential land.

- 15The correlation between the percentage of single-family zoning and median home values is 0.426 for all cities, although it is 0.303 for communities with the highest amount of single-family-only zoning and 0.591 in communities with the least percentage of single-family zoning. This means that the theorized impact of highly restrictive zoning on home values is most strongly observed in communities with the lowest level of restrictive zoning.

- 16Department of Community Development, “Flood Zone Update,” City of Woodland, updated 2012, accessed July 5, 2022, https://www.cityofwoodland.org/557/Flood-Zone-Update.

- 17Stacey Tamagni, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, (Folsom, CA: Office of Management & Budget Financial Services Division, 2020), 205, https://www.folsom.ca.us/home/showpublisheddocument/5495/637523463582970000.

- 18In both the Bay Area and Greater LA reports on single-family zoning, outcomes on these four educational metrics improved as the percentage of single-family-only zoning increased. That is, municipalities with the greatest percentage of land reserved for single-family zoning saw the highest number of students meeting 4th grade proficiency benchmarks, the highest high school graduation rates, and the highest percentage of residents with bachelor’s degrees. The group of municipalities with the second highest percentage of single-family zoning saw the next best outcomes, and the group with the least saw the lowest outcomes on these indicators. When Davis and Folsom, CA - two outliers in this analysis on several fronts described above - are removed from the data and the analysis of educational outcomes is run again, the trend seen in the two previous reports is also observed for the Sacramento region. This suggests that the trend of improved educational outcomes among areas with high single-family zoning holds true for most cities in the Sacramento region.

- 19Lauren Zeise and Jared Blumenfeld, CalEnviroScreen 4.0, (Sacramento, CA: California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2021), 8, https://oehha.ca.gov/media/downloads/calenviroscreen/report/calenviroscreen40reportf2021.pdf.

- 20The smoothed lines in Figure 7 are created using LOESS (locally weighted least squares regression). It shows the moving regression which fits local relationships between environmental health factors to the single-family portion of the residential land.

- 21Stephen Menendian et al., “Single-Family Zoning in the San Francisco Bay Area: Characteristics of Exclusionary Communities” (Berkeley, CA: Othering & Belonging Institute, October 7, 2020), citing San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, City of San Francisco 2019 Annual Water Report, (San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, 2019), https://web.archive.org/web/20200516232428/https://sfwater.org/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=15360.

- 22"Lead Poisoning," World Health Organization, October 11, 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health.

- 23 As a caveat, we are measuring the degree of restrictive zoning today, which is not necessarily the same as was the case a generation ago, although there is likely a strong correlation.

- 24The Opportunity Atlas (Boston, MA: Opportunity Insights, Harvard University, 2019), accessed October 2, 2020, https://www.opportunityatlas.org/.

- 25This opportunity map uses the same methodology as the state’s TCAC Opportunity Map but all tracts within Councils of Governments (COGs) are scored against each other. Tracts that do not fall within a COG are scored against tracts within their county. By comparison, the TCAC opportunity map uses TCAC regions as the reference geography. The TCAC/HCD map also scores rural areas separately because rural affordable housing developments compete in a separate funding pool, but such a distinction is not made here.

- 26“Regional Housing Needs Assessment,” Sacramento Area Council of Governments, https://www.sacog.org/regional-housing-needs-allocation-rhna.

- 27Heather Bromfield and Eli Moore, Unfair Shares: Racial Disparities and the Regional Housing Needs Allocation Process in the Bay Area, (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2017), http://belonging.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/haasinstitute_unfairshares_rhnabayarea_publish.pdf.

- 28Division of Housing Policy Development, “Annual Progress Report Permit Summary Table (K2 - AN542),” RHNA 5th Cycle Full Summary, (Sacramento, CA: California Department of Housing and Community Development, 2019), https://www.hcd.ca.gov/community-development/housing-element/docs/annual_progress_report_permit_summary.xlsx. For a grade ranking of cities by RHNA performance, see Nikie Johnson and Jeff Collins, “Report Card: California Cities, Counties Failing Again on Affordable Housing Goals,” The Orange County Register, January 31, 2021, https://www.ocregister.com/2021/01/31/report-card-california-cities-counties-failing-again-on-affordable-housing-goals/.

- 29Central Business District Coordinates Dataset, (2013), distributed by Daniel Hartley, https://www.danielaaronhartley.com/.

- 30For greater detail on notable zoning surveys, see footnote 4 in Stephen Menendian et al., "Single-Family Zoning in the San Francisco Bay Area: Characteristics of Exclusionary Communities," (Berkeley, CA: Othering & Belonging Institute, 2020), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/single-family-zoning-san-francisco-bay-area.

- 31See report the paragraphs that contain footnotes 5-9 in the section “Difficulties with Zoning Research and Limitations of Existing Zoning Datasets” in Menendian et al., "Single-Family Zoning in the San Francisco Bay Area: Characteristics of Exclusionary Communities," (Berkeley, CA: Othering & Belonging Institute, 2020), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/single-family-zoning-san-francisco-bay-area. For an example of a report presenting zoning figures using the ACS sampling, see: Western Economic Services LLC, 2015 Suffolk County: Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice, (Suffolk County Department of Economic Development and Planning, 2015), 39, https://suffolkcountyny.gov/Portals/0/formsdocs/ecodev/Community%20Development/AI%20final%20draft%202015.pdf?ver=2015-10-22-115354-200. As part of the research we conducted for this report, we compared the ACS sampling of the percentage of single-family residential units in the greater LA region with our manually collected zoning data. Given that the unit used for the ACS survey is in housing units as built, the results are very different from ours where we used the unit of residential land as zoned. Here is a link to the scatterplot (https://belonging.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/2022-02/Scatter%20Plot%20LA%20Zoning%20report.png), which illustrates the difference, and should be a warning to researchers relying on such shortcuts.

- 32Menendian et al., “Single-Family Zoning in the San Francisco Bay Area: Characteristics of Exclusionary Communities," citing Moira O’Neill, Giulia Gualco-Nelson, and Eric Biber, Comparing Perceptions and Practice: Why Better Land Use Data is Critical to Ground Truth Legal Reform, (Berkeley, CA: The Terner Center for Housing Innovation, 2019), https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/blog/comparing-perceptions-land-use-data.

- 33Sara C. Bronin, “Zoning by a Thousand Cuts: The Prevalence and Nature of Incremental Regulatory Constraints on Housing,” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy (2021): 23, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3792544.

- 34For planned development and specific plan zones where the municipal ordinance does not detail the intent and purpose enough for us to classify the entire zone, we used the standardized land use class from SACOG to categorize the parcels.

- 35The approach used in the present study differs slightly from our Bay Area single-family zoning study mentioned earlier. In our Bay Area report, mixed-use commercial zones were categorized as part of the “Non-residential” category if the zones were dominated by commercial uses regardless of whether residential uses are allowed. In our present study, commercial mixed-use zones are classified as “Other residential” if these zones permit residential uses according to the city ordinance, regardless of the dominant uses as suggested by the built environment. The rationale behind this divergence is our intention for the results in the present study to reflect the zoning code text even more directly, instead of basing it on the built environment, as was the approach we used in a few ambiguous mixed-use zones in our Bay Area study. We do not believe that this significantly changes the overall results or the comparability of the maps, but we note it nonetheless.

- 36Esri. “ArcGIS Hub”, ArcGIS Hub, accessed July 8, 2022, https://hub.arcgis.com/search.

- 37See e.g. Sara C. Bronin et al., Connecticut Zoning Atlas, (New York, NY: Desegregate Connecticut, 2022), https://www.desegregatect.org/atlas.