As part of our Single-Family Zoning analysis for the San Francisco Bay Area, Greater LA Region, Sacramento Region and San Diego, we identified the distribution of single-family zoning in each city, unincorporated area and broader region. On those pages, we shared our findings regarding the observed relationship between single-family zoning and socio-demographic indicators, including racial demographics, intergenerational mobility and levels of racial residential segregation. We also identified cities in each region that could benefit from zoning reforms allowing equitable development and mitigating harms of single-family-only zoning.

The Zoning Reform Tracker

The Othering & Belonging Institute is proud to launch the Zoning Reform Tracker and share information on municipal zoning reform efforts across the United States.1 The Zoning Reform Tracker is meant to serve as a hub for documenting zoning reform efforts in the country.2 It is our belief that anti-density zoning ordinances play a powerful role not only in propagating race- and class-based exclusion, but in shaping life outcomes for children in communities, and therefore in furthering patterns of negative intergenerational stratification.3 Restrictive zoning is a powerful mechanism for hoarding resources, with great implications for racial residential segregation,4 and the former will not fundamentally change without reforming or overriding zoning regulations at the municipal level.5

In the first version of the Zoning Reform Tracker, we focus specifically on municipal zoning reform efforts. Throughout this project, we use the phrase zoning reform effort or initiative, because some of the events we track are not merely successful adoptions of zoning reforms, but are their ongoing status, as well as their denials, failures, false starts, and informal legislative tablings.

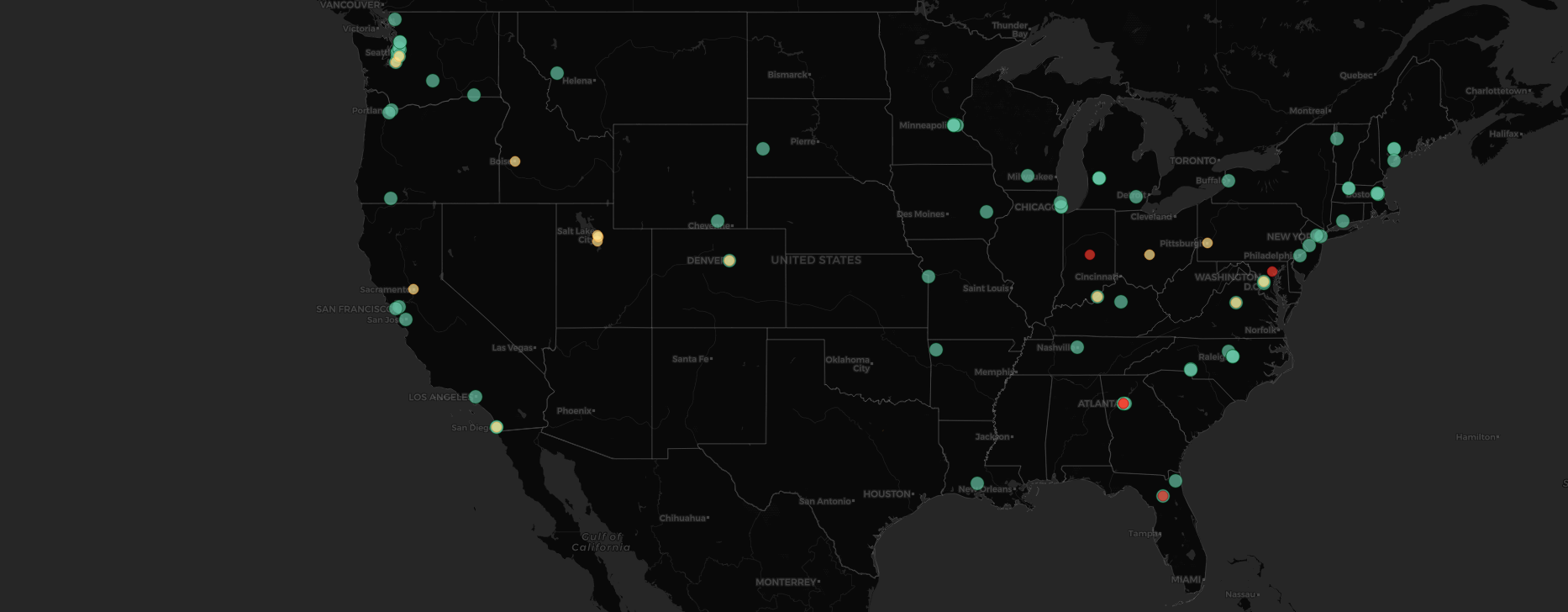

There are two components to the Zoning Reform Tracker: the database, and the webmap. The database is a sortable list of municipalities which have had some character of a zoning reform initiative, and inclusive therein are columns that describe various components of a given reform initiative. The database is then our most detailed collection or representation of zoning reform efforts across the United States. The webmap, on the other hand, is an interactive national map that marks the points of each reform initiative, and allows the user to explore the question of location, in terms of zoning reform initiatives occurring at the municipal level across the United States.

In separate documentation on the navigation menu on the right-hand side of this page, we have subpages that explain the variables used in our tracker, including one which specifically establishes an overview of the variables, as well as others which focus on the zoning reform mechanism, phase, and type. The latter three are the most important classes of how we group zoning reform efforts, and they constitute the triad of typologies which are important for our organization and representation of reform.

We created this tracker because, to the best of knowledge, there is no other single repository tracking such reform.6 The tracker attempts to be comprehensive, and so we will periodically add reform efforts as we become aware of them. Please fill out this Google Form if you feel we are missing something or our information is inaccurate.7 As we update these tracking tools with new data or information, we’ll reflect those changes in our database and webmap, as well as in the supportive documentation.8

Comprehensively, we believe that this is an important tracker that can not only inform the public, but can also provide support for advocacy efforts across the United States.9

Interactive Webmap

Click here to expand the webmap for full-screen viewing. For more information on the webmap fields, look towards the supportive documents at the right hand side of this page. And for an extensive look at the data represented herein, look towards the database below, which has additional fields not represented in the webmap above.

Sortable Database

The sortable database below presents all of the fields that we record in our tracker; please note that you can scroll to the right to see several other columns that aren’t initially visible. Furthermore, you can click and select any of the filter tabs below to narrow your search: either by the name of a jurisdiction or by the subclass of one of our typologies. You can also combine a jurisdiction filter and a typology filter to get more specific results. To reset the results just go back to 'Any' for each filter, or refresh the page.

| Municipality Name | State Name | State Short | Reform Mechanism | Reform Phase | Reform Type | Legislative Number/Policy Name | Time Status | Primary Source | Secondary Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchorage | Alaska | AK | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | AO No. 2022-80(S) | Adopted on 11/22/2022 | https://www.sightline.org/2022/11/23/anchorage-assembly-unites-to-end-parking-mandates/#:~:text=Anchorage%2C%20Alaska%2C%20has%20eliminated%20all,differences%20with%20a%20unanimous%20vote. | https://www.muni.org/Departments/Assembly/PressReleases/SiteAssets/Pages/Parking-Minimum-Ordinance/AO_2022-80%28S%29_1_T21_PARKING_AND_SITE_ACCESS_--_11-16-2022.FINAL.DOCX.DOCX.pdf | The City of Anchorage adopted an ordinance which removed mandatory parking minimums from the city. The policy goals of this reform were threefold. First, the city intends to make multi-family housing more affordable to build. Second, the city intends to encourage adaptive reuse of underutilized and vacant properties. Third, the city intends to encourage non-automobile forms of mobility and walkability. |

| Anchorage | Alaska | AK | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | AO No. 2022-107 | Approved on 1/10/2023 | https://www.sightline.org/2023/03/17/anchorage-adopts-model-adu-reforms/ | https://library.municode.com/ak/anchorage/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=1218166 | The City of Anchorage adopted an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) reform ordinance, and it made three central changes. The first is that it allowed ADUs to be built on single-family zoned districts across the jurisdiction. The second is that it allowed for ADU development on multi-family and commercially zoned districts, which makes the policy more extensive than many others enacted in the US. The third is that it reduced certain owner occupancy requirements for building or renting an ADU. Lastly, it seems that the city has intentions of making the ADU process public-facing and as accessible as possible, to the segment of the public who could utilize the policy. |

| Anchorage | Alaska | AK | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform | AO 2023-103(S) | Approved on 12/19/2023 | https://www.muni.org/Departments/Assembly/PressReleases/Pages/Assembly-Takes-Up-Housing-Action-During-Final-Meeting-of-2023.aspx | https://www.muni.org/Departments/Assembly/PressReleases/SiteAssets/Pages/Assembly-Takes-Up-Housing-Action-During-Final-Meeting-of-2023/14.F.4.--AO%202023-103%28S%29.pdf | The Anchorage City Council approved an amendment to AO 2023-103 (S) to facilitate multi-family housing development. The amendment aligns the regulations for three- and four-unit developments with the same regulations as single-family and duplex in zones where multi-family housing is permitted under the Anchorage 2040 Land Use Plan. The amendment is included in Title 21 – Land Use. |

| Anchorage | Alaska | AK | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform, ADU Reform | Housing Opportunities in the Municipality for Everyone - HOME (AO No. 2023-87) | Approved on 6/25/2024 | https://library.municode.com/ak/anchorage/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=1301222 | https://www.muni.org/Departments/Assembly/Documents/HOME%20Initiative%20Slide%20Show%20-%20Community%20Version.pdf | The City of Anchorage adopted the HOME Initiative, which is an intensive zoning code update that will eliminate single-family zoning in certain parts of their jurisdiction along with other items. There are three important changes here. First, the initiative replaces four low-density districts with the new STFR ('Single and Two Family Residential') zoning district. Second, in addition to this new district, the jurisdiction will continue to allow ADUs on each prior single-family lot that is now redefined under the zoning code update (this is carried over from a prior reform). Third, the zoning code simplifies and reduces 11 other residential districts into other 4 simplified districts: CMR-L, CMR-M, URH and LLR (see source for more information). A caveat and limitation with this measure–and why it was prior marked as potentially constitutive of a denial or rejection of some form–is that this zoning change would exempt some sub-regions of the city, besides the Anchorage Bowl, from the elimination of single-family zoning (in particular: Girdwood and Eagle River). |

| Phoenix | Arizona | AZ | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. G-7160 | Adopted on 09/06/2023 | https://kjzz.org/content/1856841/phoenix-approves-backyard-guest-houses-bans-them-short-term-rentals#:~:text=On%20Wednesday%2C%20the%20City%20Council,along%20with%20Mayor%20Kate%20Gallego. | https://phoenix.municipal.codes/enactments/OrdG-7160/media/original.pdf | The City of Phoenix passed an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) reform which made three principal changes. First, it legalizes detached ADUs throughout all residential parcels in the city. Second, the ordinance prohibits the use of ADUs as short-term rentals. Third, it limits the number of ADUs per lot to 1. |

| Tucson | Arizona | AZ | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance 11890 | Adopted on 12/07/2021 | https://www.tucsonaz.gov/Departments/Planning-Development-Services/Planning-Initiatives/Accessory-Dwelling-Units-Code-Amendment#:~:text=The%20code%20amendment%20adopted%20by,at%20least%20650%20square%20feet. | https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/tucson/latest/tucson_az_udc/0-0-0-5276 | The City Council of Tucson adopted an ordinance to allow Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), or what they also refer to as casitas, in zones that allow residential uses. There are three main parts to this ordinance. The first is that one ADU is permitted per residential lot. The second is that there are height limits for an ADU of either 12ft, or the height of the primary structure. The last is that an ADU requires 1 additional off-street parking, but this can be waived for lots close to transit or cycling infrastructure. An important provision of this ordinance is that it will sunset in late 2026, unless extended by the city. |

| Tucson | Arizona | AZ | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | TOD Reform | Downtown Area Infill Incentive District (IID) (Ordinance No. 10710) | Adopted on 9/09/2009 | https://tucson-infill-incentive-district-iid-cotgis.hub.arcgis.com/pages/iid-background | https://www.tucsonaz.gov/files/sharedassets/public/v/1/government/city-clerks-office/administrative-action-reports/documents/rsep909.pdf | The City of Tucson adopted their Downtown Area Infill Incentive District (IID) in 2009, and it has been updated somewhat regularly in subsequent years. In its first implementation, the downtown district had two main goals. The first was to facilitate infill development. The second was to establish a transit-oriented development (TOD) program for the downtown area of the city. We include this effort into our tracker because it was an early TOD overlay which has allowed for new housing and economic development in the jurisdiction, over time. |

| Tucson | Arizona | AZ | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | TOD Reform | Downtown Area Infill Incentive District (IID) | Approved on 12/20/2022 | https://tucson-infill-incentive-district-iid-cotgis.hub.arcgis.com/pages/latest-information | https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/tucson/latest/tucson_az_udc/0-0-0-4646 | The City of Tucson adopted their Downtown Area Infill Incentive District (IID) in 2009, and it has been updated somewhat regularly in subsequent years. This update in 2022 was a major reformulation of the ordinance, which made several central changes. The first is that it allowed for residential development in industrial areas. The second is that it further incentivized affordable housing through its TOD provision. The third is that it extended the spatial coverage of the overlay. The fourth is that it removed the sunset provision of the ordinance, which would have otherwise removed the ordinance from the code if it wasn't extended by the city after a certain date. We include this effort into our tracker because it was an early TOD overlay which has allowed for new housing and economic development in the jurisdiction, over time. |

| Fayetteville | Arkansas | AR | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 6076 | Approved on 8/07/2018 | https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2018/08/30/gentle-density-making-neighborhoods-transit-ready | https://library.municode.com/ar/fayetteville/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=908253 | The City Council of Fayetteville adopted an ordinance which moderated prior developmental provisions on Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) across the city. There are three main parts to this ordinance, which together constitutes a significant change in the jurisdiction's ADU policy. The first is that two ADUs are permitted per residential lot, one attached and one detached. The second is that the maximum lot size for an ADU is now 1,200 sf (up from the 600 sf of the prior ordinance). The third is that an ADU requires 1 additional off-street parking space for units above 800 sf. |

| Culver City | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 2022-008 | Adopted on 10/24/2022 | https://la.streetsblog.org/2022/10/25/culver-city-abolishes-parking-requirements-citywide | https://culver-city.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=11337428&GUID=A9AFD187-45F5-4F89-879A-C9351BC89C40 | The City Council of Culver City adopted an ordinance that removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The ordinance made three changes. First, it formally removed parking minimums from the zoning code while also specifying that such a removal does not preclude the provision of parking for development. Second, it streamlined administrative processes for alternative parking methods. Third, it shifted bicycle parking requirements throughout the city. The most important change, clearly, and the one most constitutive of zoning reform is the first. |

| Oakland | California | CA | General Plan Update | Approved | Plex Reform, Other Reform | 2023 - 2031 Adopted Housing Element | Approved on 2/17/2023 | https://www.oaklandca.gov/documents/2023-2031-adopted-housing-element | https://cao-94612.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/Oakland-Adopted-Housing-Element-Ch-1-4-21023_2023-02-17-213804_ddow.pdf | The City of Oakland adopted their 2023 - 2031 Housing Element, and it was subsequently approved by CA HCD following an initial request for revision from the department. This general plan update sets the intention and outline for three central changes to the city's zoning, land-use and housing policy. The first is that it identifies ways to work against single-family exclusive zoning through a missing middle housing approach. The second is that it identifies ways to build and maintain more affordable housing units across the city. The third is that it outlines tenant-supportive policy through an anti-displacement and racial justice framework. These intentions will need to be codified through ordinances in the future, and we might expect these codifications to occur within the near future. |

| Oakland | California | CA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Late Process | Plex Reform, Other Reform | Oakland 2045 General Plan | Ongoing as of 2/28/2025 | https://oaklandside.org/2023/03/16/oakland-planning-commission-single-family-zoning/ | https://www.oaklandca.gov/topics/oakland-2045-general-plan-zoning-amendments | The City of Oakland is currently working on refining their 2045 General Plan. This general plan update is slated to make three central changes. The first is that it will implement missing middle housing updates that'll expand the formerly Two-Family district into a Two-to-Four Family district, and allow up to 4-units to be built in more areas across the city. The second is that it will create an affordable housing overlay zone and a housing site overly zone, both of which will expand ministerial approval and height/density incentives for developments that meet certain conditions. The third is that it will approach industrial rezoning through an environmental justice perspective, to reduce impacts on at-risk geographies and communities. According to the city, the public review period for these changes ended in May 2023; though it is unclear when exactly these changes may be adopted and then, further codified, by the city. |

| San Diego | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. O-21254 | Passed on 10/30/2020 | https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/politics/story/2022-01-15/large-package-of-housing-reforms-including-changes-to-adu-rules-heading-to-san-diego-council | https://docs.sandiego.gov/council_reso_ordinance/rao2020/O-21254.pdf | The City of San Diego passed an ADU amendment which was seen as being one of the most progressive in the state of California. This ordinance made three central changes. First, it permitted attached and detached ADUs on single-family zoned lots. Second, it specified that both owner occupancy and minimum parking were not requirements for the establishment of an ADU. Third, a measure which made this ordinance distinct from many others, is that it instituted an affordable housing bonus program for ADUs. Concerning the bonus program, it allows an additional ADU to be permitted for every ADU that meets the low-income or moderate-income affordability bracket, effectively allowing multiple ADUs to be established on a single lot. |

| San Diego | California | CA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | ADU Reform, Other Reform, TOD Reform | Homes for All of Us: Housing Action Package (Ordinance No. O-21439) | Passed on 3/11/2022 | https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/politics/story/2022-02-08/san-diego-oks-large-package-of-housing-incentives-including-accessory-units | https://docs.sandiego.gov/council_reso_ordinance/rao2022/O-21439.pdf | The City of San Diego passed their "Homes for All of Us" housing and zoning amendment package. This package is too large to summarize in brief, but we will focus on its three most significant domains. First, it set the stage for a minor future concession to the city's ADU Bonus program, whereby the deed-restriction for very low and low-income affordability was reduced from 15-years to 10-years. Albeit following this concession, the city's ADU ordinance is still likely the least restrictive and most progressive in the state. Second, the ordinance instituted seven new housing incentive programs, including at least one for transit-oriented development. Third, the ordinance specified that a property owner seeking to build an ADU can either go the route of the city's ordinance, or the route of the state law, or SB 9; but not both. |

| San Diego | California | CA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | Other Reform | Homes for All of Us: Housing Action Package 2.0 Amendments | Passed on 09/21/2023 | https://www.axios.com/local/san-diego/2023/09/22/city-housing-reforms-mayor-gloria | https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/pc-23-009_housing_action_package_2.0.pdf | The City of San Diego adopted a zoning reform, which, though limited compared to its initial ambitious scope – made three central changes. First, it removes parking minimums from parcels that are within 1/2-mile to transit. Second, it allows for a 0.5 floor-area ratio (FAR) bonus for parcels with a commercial base use which are rezoned to multi-family uses. Third, it includes an incentive for off-site affordable housing development. Additionally, quite notable is that the package instituted a first right to purchase for tenants whose residencies are subject to condominium conversions. A prior version of this housing package included a provision which would have made the municipality the first in the state to implement California's SB 10, which allows single-family parcels near transit to accommodate up to 10-units. Sidestepping single-family zoning, this package made a concession to homeowner interests to focus generally on parking and development incentives. |

| San Francisco | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 311-18 | Passed on 12/11/2018 | https://usa.streetsblog.org/2018/12/17/san-francisco-eliminates-parking-minimums/ | https://sfgov.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3709260&GUID=C36405A9-974A-4B08-8EDB-56DDFAC6CEEA | The City of San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance that removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The city's reasoning behind the reform is that: A) a planning department study found that parking minimums add $20-50k more to the cost of an apartment, and B) that excessive parking incentivizes driving, leads to traffic and may form infrastructure which isn't suited for pedestrian safety. The jurisdiction joins a growing list of other jurisdictions who have removed parking minimums from a green-climate and housing perspective. |

| San José | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | ADU Permit Program | Approved on 12/17/2019 | https://sanjosespotlight.com/san-jose-streamlines-approval-for-backyard-homes-accessory-dwelling-unit-adu-housing/ | https://www.sanjoseca.gov/business/development-services-permit-center/accessory-dwelling-units-adus/adu-ordinance-updates | The City of San José passed an ADU ordinance which made three central changes to its zoning code. First, it expanded where ADUs are allowed, now including two-family areas and any lot where a single-family residence is built. Second, it created a provision for allowing junior accessory dwelling units (JADUs) to be established, if they are attached or interior to the principal dwelling. Third, it increased clarity and reduced regulations regarding ADU dimensions, design standards, and parking. |

| San José | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 30857 | Adopted on 12/06/2022 | https://www.sanjoseca.gov/your-government/departments-offices/planning-building-code-enforcement/planning-division/ordinances-proposed-updates/parking-policy-evaluation#:~:text=The%20San%20Jos%C3%A9%20City%20Council,as%20of%20April%2010%2C%202023. | https://records.sanjoseca.gov/Ordinances/ORD30857.pdf | The City Council of San José adopted an ordinance that removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The ordinance made three changes. The first is that it removed parking minimums throughout the entirety of the city. The second is that it implemented a Transportation Demand Management (TDM) requirement for each developmental project, whereby a developer is required to choose a set of measures to reduce vehicle miles travelled and to encourage green alternatives of transport. Third, the removal of parking minimums also coincides with the city affirming an intention of flexibility for land-uses allowed in particular buildings; they have also affirmed their intention of allowing for alternative developments in otherwise unused parking lots. |

| Berkeley | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 7,751-N.S. | Passed on 1/26/2021 | https://www.berkeleyside.org/2021/01/27/berkeley-parking-reform | https://berkeleyca.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021-02-09%20Item%2004%20Ordinance%207751.pdf | The City of Berkeley passed an ordinance which removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The purpose and the intentions of the city with this reform were largely based around removing the minimums in order to: A) promote more housing, and B) disincentivize car infrastructure and promote green forms of mobility, in light of the climate crisis. An important context for this reform, besides the broad consensus in planning research showing that parking minimums are not good policy from a housing or climate perspective, is a study by the city found which that over 50% of parking in the city remains nonutilized and vacant. |

| Berkeley | California | CA | General Plan Update | Approved | Plex Reform | Berkeley 2023-2031 Housing Element | Approved on 2/28/2023 | https://www.berkeleyside.org/2023/01/19/berkeley-housing-element-zoning-demolition-elmwood-shattuck-solano | https://berkeleyca.gov/construction-development/land-use-development/general-plan-and-area-plans/housing-element-update | The City Council of Berkeley approved their Housing Element, following an initial rejection from the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). The plan itself was initially adopted on January 18, 2023 in the Berkeley City Council, but the update was rejected by HCD because it didn't go far enough in: A) specifying how the city would upzone higher opportunity communities, and B) making technical changes in the permitting process which would make fulfilling the city's building goals more feasible. The new housing element made three central changes. The first is that it allowed property owners to establish plex multifamily units in areas which were before only limited to single-family property. The second is that it removed barriers from the approval process by doing away with public hearing provisions. The third is that it intentionally identified certain streets to upzone, and to specifically focus efforts on for future multifamily development, throughout the city (College, Solano and Shattuck Avenues). It may be expected that these directives will be codified through ordinances hereafter. |

| Los Angeles | California | CA | Ballot Measure | Approved | TOD Reform | Build Better LA Initiative | Approved on 11/7/2016 | https://bca.lacity.org/measure-JJJ | https://clkrep.lacity.org/onlinedocs/2016/16-0684_ORD_184745_2-15-17.pdf | In the City of Los Angeles, ACT-LA, a coalition of organizations focused on transit, housing and labor, organized to get Measure JJJ on the 2016 ballot. The measure itself passed in November 2016, and resulted in the amendment of the LA Municipal Code which created the Transit Oriented Communities (TOC) program, which is a part of the larger Build Better LA Initiative. This program itself instituted an incentive system to create more dense construction of rental housing near major transit corridors and stations. An important feature of the program is that it mandated a certain share of affordable housing in each development for residents at different income brackets, which is part and parcel of its inclusionary requirement. Lastly, the program instituted hiring preferences for local labor if the building project meets certain conditions. |

| Sacramento | California | CA | General Plan Update | Approved | Plex Reform, TOD Reform | 2040 General Plan Update | Adopted on 2/27/2024 | https://www.cityofsacramento.gov/community-development/planning/long-range/general-plan/2040-general-plan | https://sacramentocityexpress.com/2024/02/28/new-general-plan-puts-sacramento-at-the-forefront-for-housing-friendly-policies/#:~:text=The%20Sacramento%20City%20Council%20adopted,for%20the%20next%20two%20decades. | The City of Sacramento adopted 2040 General Plan Update. This general plan has provisions for instituting duplexes, fourplexes and other forms of missing middle housing, in all residential zoned land throughout the city. The plan also includes transit-oriented development policies and encourages housing construction near transit to reduce dependence on cars. |

| San Francisco | California | CA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform | Ordinance No. 210-22 | Approved on 10/28/2022 | https://www.sfchronicle.com/sf/article/S-F-housing-crisis-New-fourplex-law-poised-to-17515571.php | https://sfbos.org/sites/default/files/o0210-22.pdf | The City of San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance that allowed single family zoned areas to build fourplexes, and six-units on corner lots. A prior complication with this ordinance was that its earlier text, which removed single-family zoning in the city, may have had the effect of exempting the city from CA state's SB9 lot split and ADU law. Within the current legislative state of the city, a homeowner trying to expand their property can do so through the SB9 ministerial ADU process, or through the process outlined in this municipal ordinance. |

| Denver | Colorado | CO | General Plan Update | Approved | ADU Reform, TOD Reform | BluePrint Denver | Adopted on 4/22/2019 | https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Lessons_in_Land_Use_Reform.pdf | https://www.denvergov.org/media/denvergov/cpd/blueprintdenver/Blueprint_Denver.pdf | The City Council of Denver, as a part of their Comprehensive Plan 2040, created the BluePrint Denver document, which is a land use and transportation supplement of the broader general plan. BluePrint Denver created recommendations to allow Plex development in single-family zoned areas in the city, as well as changes which made ADU construction a target for the city, and a more feasible option for creating housing across greater segments of the city. |

| Denver | Colorado | CO | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | ADU Reform, TOD Reform | Advancing Equity in Rezoning | Enforced on 02/25/2025 | https://www.denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Community-Planning-and-Development/Denver-Zoning-Code/Text-Amendments/Advancing-Equity-in-Rezoning#section-4 | https://www.denvergov.org/files/assets/public/v/1/community-planning-and-development/documents/zoning/text-amendments/advancing-equity-in-rezoning/aeir_strategy_report.pdf | The Denver City Council approved the “Advancing Equity in Rezoning” initiative. This initiative aims to make the rezoning process more transparent, equitable, and accessible by improving public engagement and revising review criteria. It seeks to update and restructure rezoning criteria to remove outdated language, simplify the process, and ensure decisions align with citywide goals, informed by community input. Additionally, it enhances public participation by expanding notification requirements to tenants, improving outreach materials, and making rezoning information more accessible online. “BluePrint Denver,” the city's land use and transportation plan, which is a supplement to the Comprehensive Plan 2040, called for enabling at least three central zoning reforms. The first is allowing plex development on single-family lots, the second is expanding where ADUs are permitted across the city, and the third is creating incentive structures for rental housing development in transit-dense areas. |

| Englewood | Colorado | CO | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | ADU Reform, Other Reform | CodeNext: Unified Development Code | Approved on 09/25/2023 | https://www.engaged.englewoodco.gov/codenext | https://coloradocommunitymedia.com/2023/09/26/codenext-gets-final-approval-in-4-3-vote-by-englewood-city-council/ | The City Council of Englewood adopted “CodeNext,” a comprehensive rewrite of the Unified Development Code that regulates zoning and development in the city.This is the first comprehensive review of the city's regulations on new construction and redevelopment in 20 years. There were many changes in zoning and land use specifically regarding ADUs. These include:allowing ADUs to be built in R-1-A and R-1-B zoning for the first time; allowing up to three ADUs to be built in R2B, MUR3A, MUR3B, MUR3C, and R2A’s corner lots, provided that two ADUs are attached to the main residence; the elimination of owner occupancy requirements for ADUs; the elimination of additional parking requirements for ADUs, and an increase in ADU size allowances. In addition to changes to ADUs, the reform also includes a loosening of the definition of a household to four unrelated adults and their dependents, a lowering of the lot size standard to promote the construction of smaller homes with the aim of increasing affordable housing and rental income, and the design of roads for pedestrians and cyclists. |

| Hartford | Connecticut | CT | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Amendment of 11-28-2017 | Adopted on 11/28/2017 | https://usa.streetsblog.org/2017/12/13/hartford-eliminates-parking-minimums-citywide/ | https://library.municode.com/ct/hartford/ordinances/zoning_regulations?nodeId=1168243 | The City of Hartford adopted an ordinance which removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. This change occurred following more more piecemeal, yet extensive, policy from the city in the past, which saw the removal of parking minimums in downtown, as well as the removal of parking minimums for retail and service commerce across the entirety of the city. |

| New Haven | Connecticut | CT | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Amendments to allow Accessory Dwelling Units in RM-1,RM-2,RS-1 and RS-2: and to reduce Minimum Lot size to 4000 SF | Passed on 10/4/2021 | https://www.newhavenindependent.org/article/adus1 | https://newhaven-ct.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=4931185&GUID=3311B149-7880-4AA3-86DC-A763853E37C7&Options=ID%7CText%7C&Search=accessory | The Board of Alders of New Haven approved an ordinance which made it easier for homeowners in single-family areas to build attached ADUs. The ordinance itself is a part of the city's intention to phase in ADUs into single-family zoned areas, and the ordinance may be a stepping stone towards future legislation allowing detached ADU structures. To conclude, as of yet, the municipal code of the city merely allows ADU construction in the form of garages, attics, and basements, or other 'existing' structures, but not building detached ADUs from scratch. |

| Norwalk | Connecticut | CT | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | Other Reform | Norwalk Zoning Regulations Update | Effective on 2/19/2024 | https://www.thehour.com/news/article/norwalk-passes-citywide-zoning-rewrite-18554225.php | https://zonenorwalk.com/public-draft/ | The Common Council of Norwalk passed and implemented a zoning code update that can primarily be known as a form-based code update (in commercial and multi-family regions). There were plans to make more significant changes to density in single-family zoned areas but this prospective set of reform was removed after communal pushback. It seems that the recommended set of updates largely included increasing the built capacity of certain single-family zoned areas to a two-family ceiling over time, and a recommendation for more parking spots per parcel in such zoned areas. While the passed and implemented intensive zoning code update lacked a substantial change to single-family districts, we may regard the form-based settlement as a minimal advancement in a city that hasn't considered an update of this kind in years. |

| Washington | District of Columbia | DC | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Zoning Regulations Rewrite | Effective on 9/06/2016 | https://dc.urbanturf.com/articles/blog/want-to-build-an-adu-here-are-some-basics/14165 | https://dcoz.dc.gov/page/dc-zoning-history | The District of Columbia (DC) Council passed a zoning code update which permitted ADUs on many residential zoning districts. A caveat of the ordinance is that in order to rent an ADU unit, the owner needs to apply for and attain a Residential Rental Business License from the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs. A limitation with this ordinance may be that it is administratively burdensome, which has limited the extent to which the ordinance has, in actuality, facilitated ADU construction across the district. |

| Jacksonville | Florida | FL | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 2022-448-E | Approved on 11/9/2022 | https://www.jacksonville.com/story/news/politics/government/2022/11/18/jacksonville-city-council-passes-bill-allowing-accessory-dwelling-units/10699346002/ | https://jaxcityc.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=5687568&GUID=78C6D541-91EC-4D9A-AD56-A326DDAA2810&Options=&Search= | The City Council of Jacksonville approved an ordinance, called the "Keeping Families Together Act," which allowed detached or attached ADUs on single-family zoned areas. A limitation with the ordinance is that an ADU is not permitted without exception, and may be denied due to a homeowner association rules for a neighborhood. So while this ordinance allows ADUs, its method of permitting doesn't preempt other local restrictions which may reduce its effectiveness. |

| Gainesville | Florida | FL | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform | Ordinance No. 211358 | Adopted on 10/17/2022 | https://www.gainesville.com/story/news/2022/10/17/exclusionary-zoning-gone-gainesville-after-city-commission-vote/10522673002/ | https://library.municode.com/fl/gainesville/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=1179374 | The City Commision of Gainesville passed two essential ordinances which essentially removed single-family zoning in the jurisdiction. This is the most important ordinance of the two which we include in our tracker, and it did a few things. The first is that it replaced the Residential Single Family districts with a broader Neighborhood Residential (NR) zoning district. The second is that it established that in the NR district, plex development (inclusive of duplexes, triplexes, and in some cases, fourplexes) is permitted. The third is that it established that its provisions aren't subject to a sunset, but will last in permanence, into the future; in line with this, the ordinance amends both the zoning code, as well as the general plan. (The other ordinance which we do not record in our tracker is Ordinance No. 211359.) |

| Gainesville | Florida | FL | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 211262 | Adopted on 11/22/2023 | https://www.mainstreetdailynews.com/govt-politics/gainesville-developers-set-parking-numbers | https://library.municode.com/fl/Gainesville/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=1190188 | The City Commission of Gainesville adopted an ordinance that removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The ordinance made three changes. First, it removed parking minimums throughout the entirety of the city and for all land-use types. Second, it established a parking maximum. Third, it requires that any development exceeding 200 parking spaces needs to construct a structured parking facility along with the main development. |

| Gainesville | Florida | FL | Municipal Ordinance | Denied/Rejected | Plex Reform | File No. 2023-162 | Rejected on 4/19/2023 | https://www.wuft.org/news/2023/04/20/gainesville-commissioners-continue-undoing-single-family-zoning-laws/ | https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-02/how-gainesville-s-yimby-zoning-reform-was-undone | The City Commision of Gainesville, newly seated following the local election, set intentions to reverse the prior ordinances which eliminated single-family zoning in the city. Following the adoption of the ordinances, the city received threats of looming legal challenges from the state of Florida, principally the state's Department of Economic Opportunity. The city also received resistance from local community members. The Commision has formally reversed its prior ordinances with 3-ordinances based around restoring exclusionary zoning, and specifically, with the purpose of removing the formerly instated 'Neighborhood Residential' district from the city's zoning code. Gainesville is likely the most prominent case wherein a jurisdiction instituted a positive zoning reform, and then reversed and/or rejected it eventually, due to political factors. |

| Atlanta | Georgia | GA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 2018-11 (18-O-1023) | Approved on 5/16/2018 | https://www.atlantaga.gov/government/departments/city-planning/zoning-reform | https://www.atlantaga.gov/home/showpublisheddocument/39261/636821161394270000 | The City Council of Atlanta, following a commissioned team that was formed to assess its zoning code, sought to make substantial changes to the Atlanta Zoning Ordinance. This ordinance was a part of the first phase of those changes, which the city defined as "quick fixes" to the code. This ordinance made three central changes, exactly. The first is that it increased the maximum allowable height of ADUs, the second is that it increased the maximum allowable size of ADUs, and the third is that it clarified accessory uses in residential subdivisions. |

| Atlanta | Georgia | GA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 2019-09 (18-0-1581) | Approved on 1/31/2019 | https://www.atlantaga.gov/government/departments/city-planning/zoning-reform | https://library.municode.com/ga/atlanta/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=939835 | The City Council of Atlanta, following a commissioned team that was formed to assess its zoning code, sought to make substantial changes to the Atlanta Zoning Ordinance. This was a part of the second phase of those changes, which the city defined as "medium fixes" to the code. This ordinance did two things, exactly. The first is that it specified the total number of units on a parcel in accommodation of ADUs, and the second is that it removed parking requirements for ADUs. |

| Atlanta | Georgia | GA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Early Process | ADU Reform, Plex Reform | Atlanta Zoning 2.0 | Ongoing as of 2/28/2025 | https://atlzoning.com/ | https://atlzoning.com/explore-and-learn/ | The City of Atlanta is engaging in a multi-year zoning code rewrite project. The purpose of this effort will likely be to secure and make more feasible ADU, and Plex development in single-family zoned areas throughout the city; but the exact details of the rewrite remain unspecified, as they are being established in a forward looking process. This zoning code rewrite itself is projected to conclude sometime in the Summer of 2024. |

| Atlanta | Georgia | GA | Municipal Ordinance | Denied/Rejected | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 21-O-0456 | Rejected on 12/06/2021 | https://whatnowatlanta.com/city-of-atlanta-looks-to-ease-adu-legislation-to-create-more-affordable-housing-options/ | https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c756de44d546e6335d551e0/t/6142311d9a87641d7472ee7f/1631727903825/ACDH+Text+Amendment+Fact+sheet+9.2.21.pdf | The City Council of Atlanta failed to enact an ADU ordinance drafted by Councilmember Farokhi and removed it from consideration. The ordinance would have amended the current language of the zoning code concerning ADUs, and would have made three central changes. First, it would have allowed ADUs to be built or converted throughout a broader scope of the city. Second, it would have increased the maximum allowable size of ADUs. Third, it would have removed the minimum parking requirement. |

| Atlanta | Georgia | GA | Municipal Ordinance | Denied/Rejected | TOD Reform | Ordinance No. 21-O-0454 | Terminated on 12/20/2021 | https://atlantaciviccircle.org/2021/07/20/city-legislation-seeks-to-boost-residential-density-by-transit-stops/ | http://atlantacityga.iqm2.com/Citizens/Detail_LegiFile.aspx?Frame=&MeetingID=3360&MediaPosition=&ID=24426&CssClass= | The City Council of Atlanta was considering an ordinance which would have implemented a Transit Oriented Development (TOD) policy throughout the entire city. Since it was pending in committee at the end of the 2021 quadrennial year, and Charter Section 2-407(a) was provided, this ordinance was automatically terminated at the end of the last City Council meeting in December 2021. This ordinance would have worked principally through rezoning transit stops near high traffic stations. Specifically, Low-Density Residential zones within half a mile of high-capacity transit stations would have been upzoned to Multifamily Residential Multi-Use (MR-MU). The outcome was that the ordinance was essentially "referred," meaning filed away, or softly struck down. |

| Decatur | Georgia | GA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform | "Missing Middle Housing" Ordinance | Approved on 2/06/2023 | https://www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/news/2023/02/07/decatur-city-commission-missing-middle-final-vote.html#:~:text=At%20a%20Monday%20meeting%2C%20Decatur,converted%20into%20those%20new%20uses. | https://www.decaturga.com/sites/default/files/fileattachments/planning_and_zoning/page/16881/missing_middle_one_page_summary_decatur.pdf | The Decatur City Commission, following a recommendation from its Affordable Housing Task Force, approved an ordinance which legalized Plex development on single-family zoned districts. This ordinance made at least two significant changes to the city's prior code. The first is that it allowed duplex and (up to 4-unit) walk-up flats to be built in single-family zoned areas, and the second is that it allowed single-family homes themselves to be converted into these missing middle housing types. |

| Boise | Idaho | ID | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | Plex Reform, ADU Reform, Other Reform | Modern Zoning Code | Approved on 6/15/2023 | https://boisedev.com/news/2023/03/23/boise-zoning-code-rewrite-2/ | https://issuu.com/cityofboise/docs/pds-modernzoningcode-executivesummary-finaldraft-2 | The City of Boise passed a well-rounded zoning reform, which makes three central changes. First, the zone expands development of the R-1C zone (previously confined to single-family dwellings and duplexes) to accomodate ADUs, duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes. Second, the code sought to prevent speculation and assure affordability by requiring that adding more than 2-units in this prior R-1C district must be joined with such units meeting affordability standards (at 80% of the AMI if the new units are rentals). Third, the code update requires a conditional use permit for multi-family dwellings in mixed use districts that displace vulnerable tenants. |

| Chicago | Illinois | IL | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | TOD Reform | Connected Communities Ordinance (Ordinance No. O2022-2000) | Passed on 7/20/2022 | https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/mayor/press_room/press_releases/2022/july/PassesConnectedCommunitiesOrdinance.html | https://chicago.councilmatic.org/legislation/o2022-2000/ | The City of Chicago passed the Connected Communities Ordinance, which is a codification of a selection of equity-based improvements from a study made by the city of its preceding TOD policy. The ordinance itself is intended to make three changes. The first is to more equitably site TOD developments, without commensurately creating displacement. The second is to expand the policy's existent financial incentives. The third is to implement different ways of making streets safer for pedestrians, cyclists and transit users, around TOD sites. |

| Chicago | Illinois | IL | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. SO2020-2850 | Adopted on 12/16/2020 | https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/doh/provdrs/homeowners/svcs/adu-ordinance.html | https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/doh/adu/adu_ordinance.pdf | The City of Chicago adopted an ordinance which permitted ADU construction in 5-pilot areas across the city. According to the ordinance, all R-residential zoned areas, except for the residential single-family zoned areas (RS-1), are permitted to have ADUs. Furthermore, ADUs may be accessory to a primary dwelling unit, or internal to it, or constructed on multifamily zoned districts as well; in the latter case, depending on the density of the lot, the ordinance permits up to 4-interior ADUs. The ordinance also has affordability standards which go into effect after the construction of 2 or more units. |

| Evanston | Illinois | IL | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 86-O-20 | Adopted on 9/29/2020 | https://www.washingtonpost.com/realestate/accessory-dwellings-offer-one-solution-to-the-affordable-housing-problem/2021/01/07/b7e48918-0417-11eb-897d-3a6201d6643f_story.html | https://library.municode.com/il/evanston/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=1048614 | The City of Evanston adopted an ADU ordinance which made three central changes. The first is that it permitted both attached and detached ADUs in single-family zoned areas throughout the city. The second is that it specified a maximum size of 1,000 sqft for ADUs, which is slightly greater than most other jurisdictions. The third is that it specified that no additional parking space is required for adding an ADU to a lot. |

| Carmel | Indiana | IN | Municipal Ordinance | Denied/Rejected | ADU Reform | "Accessory Dwelling Units" Ordinance | Denied on 2/15/2021 | https://www.indystar.com/story/news/local/hamilton-county/2021/02/18/carmel-city-council-rejects-granny-flats-accessory-dwelling-units-proposal/6798672002/ | https://www.youarecurrent.com/2021/02/16/carmel-city-council-votes-not-to-change-process-for-adding-in-law-quarters/ | The City of Carmel was considering an ordinance which would have made ADUs more numerous and easy to build on single-family zoned land in the city. The ordinance would have accomplished this in two main changes. The first is that it would have reduced the difficulty of the ADU application process by removing the requirement to apply to the Board of Zoning Appeals for approval. The second is that it would have required that 20% of new residential lot development have an ADU. Due to conflict in the council, and dilutions of the original ordinance, the amended ordinance was eventually struck down in the council. The current process for constructing or converting an ADU in the city requires a homeowner interested in this form of development, to apply for approval through the Carmel Board of Zoning Appeals. |

| Richmond | Indiana | IN | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | ADU Reform, Other Reform | Ordinance No. 22-2023 | Approved on 8/21/2023 | https://www.richmondindiana.gov/resources/august-2023-udo-update | https://portal.laserfiche.com/Portal/DocView.aspx?id=178240&repo=r-979ae874&preview=ZzbKa7B | The City of Richmond approved an intensive zoning code update which made a variety of changes. These changes range from permitting solar panels in residential areas, to increasing multi-family residential density for certain multi-family districts. Most centrally, they made accessory dwelling units (ADUs) a permitted use in single-family residential parcels in the city. |

| South Bend | Indiana | IN | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Article 21-07: Access & Parking | Adopted on 9/17/2021 | https://www.greaterohio.org/blog/2021/2/9/south-bend-indiana-council-votes-to-eliminate-parking-requirements-citywide#:~:text=Previously%2C%20the%20City%20of%20South,this%20change%20(Guevara%202021). | http://docs.southbendin.gov/WebLink/0/edoc/380145/21-07%20Access%20and%20Parking.pdf | The Common Council of South Bend adopted an ordinance that removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The ordinance applies to both commercial and residential developments and follows an earlier city effort, in the year of the city-wide adoption, which saw the city remove parking minimums in the designated downtown of the jurisdiction. |

| Iowa City | Iowa | IA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 21-4866 | Adopted on 11/05/2021 | https://www.icgov.org/government/departments-and-divisions/neighborhood-and-development-services/development-services/urban-planning/form-based-zones-and-standards | https://www.press-citizen.com/story/news/2021/10/06/iowa-city-council-south-district-zoning-plan-clears-first-hurdle-form-based-code-affordable-housing/5952816001/ | The Iowa City Council adopted an ordinance which instituted a form-based code for 900 acres of residential land in the South District of the city. The ordinance itself was passed with the intention of creating capacity for mixed-use and missing middle housing such as duplex and fourplexes, in the area. A limitation with this ordinance is that it only permits form-based code in a small area of the city, within the South District in particular, and not throughout the entire jurisdiction. |

| Iowa City | Iowa | IA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform, ADU Reform | Case No. REZ23-0001 | Passed on 10/17/2023 | https://www.kcrg.com/2023/10/19/iowa-city-moves-ahead-with-zoning-changes-would-make-accessory-units-more-available/ | https://www.iowa-city.org/WebLink/DocView.aspx?id=2180421&dbid=0&repo=CityofIowaCity&searchid=531c0387-38bc-40c9-84c0-3950b04a5816 | The Iowa City Council adopted an ordinance which made two central changes. First, it made duplexes an allowed use in prior single-family zoned parcels (specifically RS-5 low-density, and RS-8 medium-density single-family districts). Second, it allowed ADUs in single-family zoned parcels and also instituted a series of adjacent ADU changes: removing minimum parking requirements for ADUs, expanding allowable ADU size, and removing ADU owner-occupancy requirements. |

| Louisville | Kentucky | KY | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 092, Series 2021 | Passed on 6/24/2021 | https://louisvilleky.gov/government/planning-design/accessory-dwelling-units-adu | https://louisvilleky.gov/planning-design/document/21-ldc-0004-accessory-dwelling-ordinance | The Louisville Metro Council passed an ordinance which allowed both attached and detached ADU construction by-right in the metro, with special standards. A prior version of the code merely allowed ADUs to be established through a conditional-use permitting process, which made it considerably more difficult for them to be established. The ADU ordinance made three central changes. The first is that it allowed ADUs by-right with certain special standards. The second is that it created a provision deterring ADU construction or conversion for an absentee landlord. The third is that it prohibited ADU construction in environmentally constrained areas. |

| Louisville | Kentucky | KY | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Early Process | Plex Reform, Other Reform | Land Development Code Reform | Ongoing as of 2/28/2025 | https://louisvilleky.gov/government/planning-design/land-development-code-reform | https://louisvilleky.gov/planning-design/document/pdsadvancingequity072220pdf | The Louisville Metro Council is currently in early stages of implementing its Land Development Code (LDC) update, which will codify some of the changes established in their Plan 2040. In this code update, single-family zoning reform is situated as a priority. While it is unclear exactly the extent to which this general plan will considerably change the ubiquity of single family zoning in the jurisdiction, or land-use provisions more generally, the intention established in the planning process appears to be two-fold. First, the zoning code update will focus on missing middle housing, which may be constitutive of Plex reform, whereby the allowed density of single-family zoned areas are increased marginally. Second, the zoning code update will focus on establishing new form-based regions within the jurisdiction. Specified details of these efforts will be confirmed upon the adoption of the code update. |

| Lexington | Kentucky | KY | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 102-2021 | Passed on 10/28/2021 | https://www.imaginelexington.com/adu | https://files.amlegal.com/pdffiles/LexingtonKY/Z-102-2021.pdf | The Urban County Council of the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government, as a codification of their 2018 Comprehensive Plan, passed an ordinance focused on ADU reform in single-family zoned areas. This ordinance specifically allowed for the conversion of detached ADUs such as garages or barns, as well as construction of exterior and internal ADUs that are attached to a primary dwelling. Both types of ADUs are only permitted in single-family zoned areas. An important note is that the ordinance does require a pre-application conference with the planning department, before submitting a building permit application for the ADU. |

| Lexington | Kentucky | KY | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 113-2022 | Adopted on 10/27/2022 | https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2023/1/24/lexington-uses-nationwide-precedent-to-repeal-parking-mandates#:~:text=In%20August%20of%202022%2C%20Lexington,that%20local%20businesses%20may%20suffer. | https://files.amlegal.com/pdffiles/LexingtonKY/Z-113-2022.pdf | The Urban County Planning Commission of Lexington-Fayette County adopted an ordinance that removed mandatory parking minimums from the zoning code. The ordinance made three changes. First, it consolidated all of the disparate locations of the code where parking standards were mentioned. Second, it removed the minimum parking standards for new developmental projects. Third, it increased tree canopy and vehicle use requirements for parking lots. The jurisdiction joins a growing list of others who have removed parking minimums from a green-climate, walkability, and housing perspective. |

| Lafayette | Louisiana | LA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Lafayette Downtown Code | Amended on 3/01/2015 | https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2019/06/18/buffalo-and-lafayette-lead-way-form-based-codes | www.downtownlafayette.org/wp-content/uploads/Downtown-Lafayette-Code-2015-03-01-web.pdf | The Lafayette City Council passed a form-based amendment to their downtown code. The code update implemented a form-based design, which centers the physical form of a place as opposed to a concrete code, to encourage mixed-use development. A limitation with this code update to the Downtown Plan is that the revision itself, clearly, only pertains to the downtown area of the city, and it does not at all alter single-family zoning throughout the entirety of the city. |

| Auburn | Maine | ME | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 18-04052021 | Adopted on 5/03/2021 | https://www.auburnmaine.gov/postings/blogs/detail/Auburn-Approves-Secondary-Dwelling-Units | https://library.municode.com/me/auburn/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIICOOR_CH60ZO_ARTIIGEPR_S60-34BUPELO | The City Council of Auburn Maine adopted an ADU ordinance which made three principal changes. The first is that it expanded permitted ADU types from merely internal or attached ADUs, to detached ADUs. The second is that it removed normal size limits and greatly increased the height limits for established ADUs, so that the accessory unit can ultimately be larger than the principal dwelling. The third is that it specified that these units can be built on both single-family zoned land and also land zoned for duplexes. |

| Auburn | Maine | ME | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 19-07182022 | Adopted on 3/21/2022 | https://better-cities.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/BCP-Auburn-case-study.pdf | https://library.municode.com/me/auburn/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=PTIICOOR_CH60ZO_ARTIVDIRE_DIV3LODECOREDI | The City Council of Auburn Maine adopted a form-based code ordinance, which we have characterized as a reform type of Other, in our type classification. This ordinance made two main changes. The first is that it rezoned just over 1,500 acres in the central part of the city to make the land more amenable to mixed-use development. The second is that, instead of implementing many regulations to this district, the city merely set the density standard of this district to 16 dwelling units per acre - which allows for somewhat dense multifamily housing. |

| South Portland | Maine | ME | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 4-22/23 | Passed on 11/01/2022 | https://www.pressherald.com/2022/11/03/south-portland-removes-restrictions-on-in-law-apartments/ | https://go.boarddocs.com/me/sport/Board.nsf/files/CHZGFC439291/$file/ORDINANCE%20-%20Ch%2027%20ADUs%20Amendments.pdf | The City Council of South Portland passed an ordinance that permitted ADUs on all residential zoned land throughout the city. The ordinance made three changes. The first is that it removed the administrative barrier of a Planning Board public hearing which was prior required to gain approval. The second is that it removed the parking requirements prior associated with ADU construction or conversion. The third is that it specified that owner occupancy is required for establishing an ADU. |

| Baltimore | Maryland | MD | Municipal Ordinance | Denied/Rejected | Plex Reform | Abundant Housing Act (Ord No. 22-0285) | Rejected on 12/4/2024 | https://ggwash.org/view/87994/two-bills-aim-to-tackle-baltimores-housing-shortage | https://baltimore.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=5845395&GUID=14D78850-8A86-4317-AA8C-A9003052FFDB&Options=&Search= | The City Council of Baltimore failed to pass an ordinance that sought to lay the way for missing middle housing, particularly through Plex development. Conditional on its adoption, this ordinance would have instituted three changes. First, it would have allowed for low-density multi-family housing, or duplex to fourplex development, on single-family zoned areas. Second, it would have allowed greater density in locations closer to public transportation hubs. Third, it would have removed parking minimums related to residential development. According to the City Council of Baltimore, the final action on the ordinance is dated December 14, 2024, and its status is “Failed - End of Term.” |

| Cambridge | Massachusetts | MA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Other Reform | Ordinance No. 2022-5 | Passed on 10/24/2022 | https://mass.streetsblog.org/2022/10/25/cambridge-repeals-all-minimum-car-parking-requirements-for-new-buildings/ | https://library.municode.com/ma/cambridge/ordinances/zoning_ordinance?nodeId=1182012 | The City of Cambridge passed an ordinance which removed minimum parking requirements from their zoning code. Specifically, it removed off-street parking requirements that had prior existed as a condition of development. The reasoning for this removal, as much research has shown, is that parking minimums make development more expensive, raise rents, and reduce the total units established for a given project; much research establishes that it is also misuse space, and encourage dependence on automobiles. |

| Boston | Massachusetts | MA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Text Amendment No. 440 | Passed on 5/08/2019 | https://www.boston.gov/departments/housing/addition-dwelling-units/adu-program#:~:text=The%20Additional%20Dwelling%20Unit%20Program,to%20build%20approved%20ADU%20designs. | https://library.municode.com/ma/boston/ordinances/redevelopment_authority?nodeId=955682 | The City of Boston adopted an ordinance, which codified a prior 18-month long pilot program, that allowed internal ADUs in lots that have 1-3 units. The ordinance itself did not allow for the conversion of an external structure on a single-family lot, nor for the construction of an ADU from scratch. Therefore, due to this ordinance only permitting an ADU so long as it works within the existing dimensions of the primary residence, it might be seen as being limited in comparison to other ordinances, which legalize lot splits and detached ADU construction. |

| Greenfield | Massachusetts | MA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. FY 17-024 | Adopted on 8/17/2016 | https://www.recorder.com/First-accessory-dwelling-unit-Greenfield-5099243 | https://berkeley.box.com/s/dfjx4f0efcpvthslnypy79nvowq88o4f | The City Council of Greenfield adopted an ADU ordinance which allowed both attached and detached ADUs in single-family land across the city. The major limitation of this ordinance was that it required a special permit in order for an ADU to be established in any given lot. The special permit process, as opposed to a ministerial review process, is not enclosed from community input - so by its nature, this first ordinance opened up a space in the approval process for community obstruction, which had the outcome of reducing the effectiveness of this measure. |

| Greenfield | Massachusetts | MA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. FY 21-026 | Adopted on 11/18/2020 | https://www.recorder.com/Accessory-dwelling-units-now--by-right--in-Greenfield-35025119 | https://berkeley.box.com/s/qegxjl0uxj8y8117apl593motlth6tao | The City Council of Greenfield adopted an ADU ordinance which amended their prior ADU policy. The main change that this ordinance made was that it removed the requirement for securing a special permit for attached and internal ADUs, which the earlier ADU ordinance had instated, and which generally makes establishing ADUs more difficult. A caveat is that a detached ADU still requires a special permit. This ordinance can be summarized in three parts. First, it allows both attached and detached ADUs on single-family zoned land. Second, it requires owner occupancy for establishing and continuing to rent an ADU. And third, it requires 2 off-street parking spots for a new ADU. |

| Somerville | Massachusetts | MA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | ADU Reform, Other Reform | Ordinance No. 2019-25 | Passed on 12/12/2019 | https://www.somervillema.gov/news/somerville-city-council-administration-pass-citys-first-zoning-overhaul-30-years | https://library.municode.com/ma/somerville/codes/zoning_ordinances?nodeId=01%20-%20Somerville,%20MA%20Zoning%20Ordinance | The City Council of Somerville passed an zoning code update, which was brought to the city by means of a "citizen petition." The ordinance fulfilled numerous directives of its Master Plan, but there are three central and important changes which it made. The first is that it increased the affordability requirements to 20% for many new developments in the city, which improved its prior inclusionary zoning policy. The second is that it permitted backyard cottages on most residentially zoned land. The third is that it implemented a form-based code throughout the entirety of the jurisdiction. |

| Gloucester | Massachusetts | MA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Denied/Rejected | Plex Reform, ADU Reform | RZ2021-003 | Rejected on 05/17/2022 | https://www.gloucester-ma.gov/1196/Zoning-Amendment-Information | https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=cQu4s2b_fqU | The Gloucester City Council rejected RZ2021-003, a series of zoning amendments that would have amended regulations related to residential uses and housing construction requirements. The proposal was initially proposed in line with the goals of the Housing Production Plan, a tool that identifies goals related to the city's housing development targets. Early proposals included increasing the number of affordable housing units, amending regulations related to single-family, multi-family, and ADU housing. The final proposals included reducing the minimum lot size in multifamily zones and increasing the maximum building height for single-family, two-family, and multifamily housing. The City Council voted four months after the initial proposed amendments were made, and rejected all of these proposals. |

| Cambridge | Massachusetts | MA | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | Other Reform | 100%-Affordable Housing Zoning Overlay | Adopted on 10/05/2020 | https://www.cambridgema.gov/CDD/housing/housingdevelopment/aho | https://www.cambridgema.gov/CDD/Projects/Housing/affordablehousingoverlay#:~:text=The%20goal%20of%20the%20100,affordable%20housing%20options%20for%20residents. | The Cambridge City Council approved a 100%-Affordable Housing Zoning Overlay (AHO) designed to allow affordable housing developers to develop affordable housing more quickly, efficiently, and permanently. The overlay was first proposed in 2018 and was discussed and considered through 2019. However, the petition expired on September 30, 2019. Then, the second zoning petition to include the AHO was submitted again in early 2020 and adopted in October 2020. Until this was approved, affordable housing developers faced long and costly permitting issues, often in areas where regulations prevented new affordable development or where they could not compete with market-rate developers who could pay more for land and buildings. The approval of this overlay will allow for the development of higher density, permanent affordable housing than is allowed under existing zoning and has created a review process that will ensure that such housing is approved efficiently. |

| Cambridge | Massachusetts | MA | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform, Other Reform | Ordinance No. 2025-1/Ordinance No. 2025-1 | Approved on 02/10/2025 | https://www.cambridgema.gov/CDD/Projects/Zoning/multifamilyhousing | https://www.boston.com/news/politics/2025/02/11/cambridge-eliminates-single-family-zoning-in-historic-move/ | The Cambridge City Council approved two zoning petitions that allow multifamily housing throughout the city. This eliminates historic exclusive single-family zoning and allows multi-family housing in all neighbourhoods. It also encourages the construction of more housing, particularly income-restricted affordable housing through the city's inclusionary housing program, eliminates requirements that had made it difficult to build multifamily housing, such as minimum lot size, housing unit limits, and maximum floor area, and reduced setback requirements. The Community Development Department indicated that up to 4,800 new units could be created in the proposed zoning. |

| Grand Rapids | Michigan | MI | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | Other Reform | Grand Rapids Zoning Ordinance | Passed on 11/05/2007 | https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Lessons_in_Land_Use_Reform.pdf | https://www.mml.org/pdf/information/form%20based%20code%20-%20Grand%20Rapids%20-%20MMR%20article%202008.pdf | The City Council of Grand Rapids passed a form-based code throughout the entirety of the city. The purpose of this early form-based reform was to allow more multi-family construction in lower density residential areas, and provide more flexible uses for property owners and businesses. While form-based reforms still implicitly depend on exclusionary frameworks of "community character" in order to function, and may therefore be subject to certain limitations, they are generally seen as changes that allow for more flexibility in land use and development, especially when compared with restrictive code-based or Euclidean zoning. |

| Grand Rapids | Michigan | MI | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform | Ordinance No. 2019-09 | Adopted on 3/26/2019 | https://www.mlive.com/news/grand-rapids/2019/03/city-approves-3-measures-aimed-at-increasing-affordable-housing.html | https://library.municode.com/mi/grand_rapids/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=950340 | The City Council of Grand Rapids passed a set of ordinances which changed its zoning code in three considerable ways. This is one of those ordinances, and it focused principally on Plex development on single-family land. This ordinance instituted two major changes. The first is that it permitted the construction or conversion of duplexes on corner lots in single-family zoned areas. The second is that it reduced the square footage requirements for these corner lot duplexes. |

| Grand Rapids | Michigan | MI | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | TOD Reform, Other Reform | Ordinance No. 2019-10 | Adopted on 3/26/2019 | https://www.mlive.com/news/grand-rapids/2019/03/city-approves-3-measures-aimed-at-increasing-affordable-housing.html | https://library.municode.com/mi/grand_rapids/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=950341 | The City Council of Grand Rapids passed a set of ordinances which changed its zoning code in three considerable ways. This is one of those ordinances, and it focused principally on inclusionary zoning and incentivizing rental housing construction near transit. The ordinance established three major sets of bonuses for certain rental housing construction. The first are configured to increase affordable housing construction. The second are configured to increase rental housing construction near transit lines. And the third are configured to increase mixed-income housing. |

| Grand Rapids | Michigan | MI | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 2019-11 | Passed on 3/26/2019 | https://www.mlive.com/news/grand-rapids/2019/03/city-approves-3-measures-aimed-at-increasing-affordable-housing.html | https://library.municode.com/mi/grand_rapids/ordinances/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=950345 | The City Council of Grand Rapids passed a set of ordinances which changed its zoning code in three considerable ways. This is one of those ordinances, and it focused principally on ADU development on single-family land. This particular ordinance has a major limitation, in that it instituted a provision for a public hearing process, which is a process wherein neighbors within 300ft of a prospective ADU development are notified, and can delay the project through public hearings. This provision is likely to reduce the effectiveness of the ordinance, and limit the extent to which ADUs may be realized in the city. Though this is the case, even with the current public hearing provision, the ADU application process is easier than it was earlier in the city, wherein there was a special land use application process required for ADUs. |

| Ann Arbor | Michigan | MI | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Amendments to the Accessory Dwelling Unit Requirement | Passed on 6/07/2021 | https://www.mlive.com/news/ann-arbor/2021/06/ann-arbor-opens-door-to-more-accessory-apartments-in-neighborhoods.html | https://www.a2gov.org/departments/planning/Documents/Planning/ADU%20Ordinance%20Amendments%20(1).pdf | The City Council of Ann Arbor passed an amendment of its zoning code, which reformed the city's ADU provisions. The ordinance made three central updates. The first is that it expanded the total eligible properties wherein one might construct or convert an ADU. The second is that is generally reduced restrictions in the application and approval process. The third is that it reduced the parking minimum, but still requires at least one off-street parking spot for an ADU if the lot isn't within a 1/4 mile of a bus stop. |

| Ann Arbor | Michigan | MI | Intensive Zoning Code Effort | Approved | TOD Reform | Ordinance No. ORD-21-19 | Approved on 7/06/2021 | https://www.michigandaily.com/news/some-ann-arbor-residents-share-concerns-about-tc1-rezoning-proposal-ahead-of-city-council-vote/ | http://a2gov.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=4966621&GUID=4E34C6AE-E4A5-4DC4-B460-124B943D8D79&Options=&Search=&FullText=1 media: https://www.mlive.com/news/ann-arbor/2021/07/ann-arbor-oks-high-density-zoning-for-transit-corridors-but-not-without-drama.html | The City of Ann Arbor approved a transit-oriented development (TOD ordinance). First, the ordinance created a new district, the Transit Corridor (TC1) district, in order to facilitate transit oriented development in the jurisdiction. This district is intended to create at least two-story housing close to transit, with the purposes of encouraging infill development, expanding multi-family housing variety and option, and generate walkable and mobile communities. |

| Saint Paul | Minnesota | MN | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform, Other Reform | Ordinance No. 22-1 (Phase 1 of the 1-4 Unit Housing Study) | Adopted on 1/19/2022 | https://www.stpaul.gov/departments/safety-inspections/building-and-construction/construction-permits-and-inspections/building-permits-inspections/accessory-dwelling-units | https://www.stpaul.gov/sites/default/files/2022-01/CC%20Ordinance%2022-1%201-4%20Unit%20Housing%20Study%20Phase%201.pdf | The City of Saint Paul passed an ordinance which updated their zoning code to be more conducive to ADU development, in line with the recommendations from their earlier 1-4 Unit Infill Housing Zoning Study. The city first allowed a narrow scope of the city to have ADUs in 2016, and then expanded ADUs to the entire city in 2018. This ordinance is an extension of those prior ordinances, and the current state of ADUs in the jurisdiction are as follows. First, ADUs are allowed on all single-family zoned districts throughout the city. Second, the owner occupancy requirement is no longer required for establishing an ADU. Third, a maximum of three ADUs can be built on lots containing one to two-family dwelling, so long as the maximum size is under 1,200sqft. |

| Saint Paul | Minnesota | MN | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | Plex Reform, ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 23-43 (Phase 2 of the 1-4 Unit Housing Study) | Adopted on 10/18/2023 | https://stpaul.granicus.com/DocumentViewer.php?file=stpaul_e26e67002baf572f97b75bb2dc1a0740.pdf&view=1 | https://stpaul.legistar.com/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=6358356&GUID=F8BB8118-1017-44D6-A1D1-029E7621E410&Options=&Search=&FullText=1 | The City of Saint Paul passed an ordinance which updated their zoning code and adopted the recommendations put forward in Phase 2 of the 1-4 Unit Housing Study. This zoning reform makes three central changes. First, it allows duplex to sixplex development throughout various residential districts; there are three districts with different maximums (RL-duplex, H1-fourplex, H2-fiveplex). Second, it instates an incentive in the H-1&2 series parcels that allows developers to build 1-2 additional units if those additional units meet certain affordability requirements (up to 80% AMI). Third, the reform allows up to 2-ADUs to be built on a single parcel for every single-family dwelling on such a parcel. While Phase 1 focused on ADUs, this law focused mainly on Plex reform and removing single-family textual predominance from the municipality. |

| Minneapolis | Minnesota | MN | Municipal Ordinance | Approved | ADU Reform | Ordinance No. 2014-116 | Approved on 12/08/2014 | https://www.minnpost.com/politics-policy/2017/05/inside-one-minneapolis-first-and-coolest-accessory-dwelling-units/ | https://lims.minneapolismn.gov/file/2014-00660 | The City of Minneapolis passed a series of ordinances to permit ADUs throughout the city. Due to the piecemeal nature of these ordinances, and the fact that only comprehensively do they really amount to an ADU reform, we have identified the single most important ordinance out of the series of 7-ordinances present in the broader effort. The ordinance made three central changes. The first is that it allowed ADUs on what was prior single-family zoned land throughout the city. The second is that it specified an owner-occupancy requirement for the construction or conversion of an ADU. The third is that it specified that no additional parking spot need be required for ADUs. |