Our new report on the Trans-Pacific Partnership raises serious concerns about the plurilateral, mega-regional trade deal, with an analysis that the TPP puts the interests of corporations before the interests of people and core democratic principles. The Haas Institute’s report analyzes the TPP from three main lenses—democratic participation, transparency, and public accountability—examining the ways in which the TPP is a particular affront to these key principles. This report was revised and re-released on May 9.

Download the revised "Trans-Pacific Partnership: Corporations Before People and Democracy."

Introduction

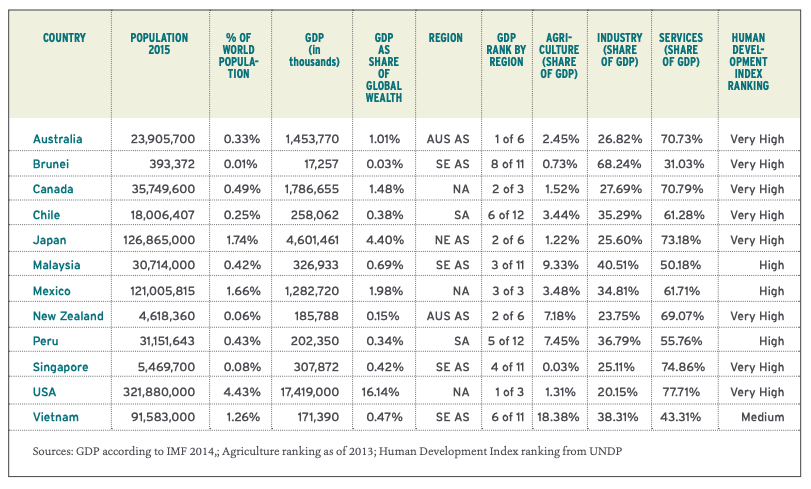

On February 4, 2016, the United States and 11 other Pacific Rim nations signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a massive plurilateral trade and investment agreement that sets rules to which all signatory countries—pending ratification by each—must conform their domestic policies covering financial and other services, intellectual property, government procurement, internet policy, state-owned enterprises and competition, food and other product standards and safety inspections, and more. The pact is designed as an enforceable regime of trade and investment governance in the Pacific Rim that reregulatesi the economic order of signatory nations in Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, geared towards the benefit of corporate interests.

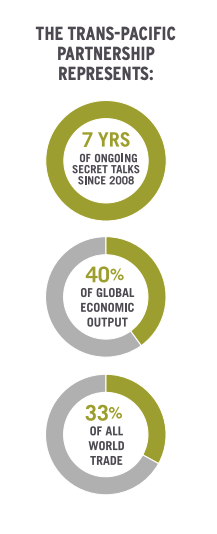

The mega-regional agreement was negotiated by Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States.ii Covering one-third of all world trade—with its signatory member countries producing 40 percent of global economic output—the TPP is the largest regional trade accord in history.1 And, because it is designed as a “docking” agreement, meaning other countries willing to meet its terms can join at any time, the initial 12 TPP countries are not intended to be the only signatories.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is one of two mega-regional trade and investment deals being negotiated simultaneously. The other is the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP)—a proposed trade and investment agreement between the United States and the European Union—which is considered to be the Atlantic counterpart of the TPP. Additionally, negotiations are underway for a major plurilateral sectoral agreement, the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA). It includes 50 countries from across the world and would cover 70 percent of the global services economy.2 iii Among the three, the Trans-Pacific Partnership is particularly significant, as it is designed to be the inaugural agreement for the proposed TPP-TiSA-TTIP triad3 , which would establish binding global rules particularly favorable for multinational and transnational corporations.iv

Underlying Assumptions vs. Reality

Supporters of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) have often argued that the pacts’ regimen of trade liberalization, investor and intellectual property rights, and regulatory policies favorable to commercial interests has far-reaching benefits.v According to the US International Trade Administration, FTAs function to open up foreign markets to US exporters and enhance investment flows to the benefit of all parties and peoples involved: “Trade Agreements reduce barriers to US exports, and protect US interests and enhance the rule of law in the FTA partner country…[via] the reduction of trade barriers and the creation of a more stable and transparent trading and investment environment.”4

Furthermore, proponents of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) have consistently advanced such narratives.5 The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) stated that the TPP is an “upgraded NAFTA” and that it would help “increase Made-in-America exports, grow the American economy, support well-paying American jobs, and strengthen the American middle class” by eliminating more than 18,000 taxes and other trade barriers on American products across the member countries of the agreement.6

Despite the claims by the US Trade Representatives and other FTAs proponents that such pacts promote progress and prosperity, our analysis in this report instead finds that the TPP presents serious challenges to the sovereignty of participating countries and the rights of their populations by increasing the relative power of corporations that, by design, are driven by profit over all else. According to Alfred-Maurice de Zayas, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Promotion of a Democratic and Equitable International Order, the TPP would “transfer regulations of corporations to corporations themselves, and away from democratically elected governments,” with respect to labor and employment, health care and medicine, the environment, and more.7

Were it to be approved by Congress, the TPP would allow corporations greater ability to evade environmental and consumer protections, limit the availability of affordable medicines,vi regulate the Internet on behalf of the content industry, and affect the movement of workers, among other outcomes.vii The TPP would also further entrench an international legal regime that allows corporations to bypass domestic courts to challenge—before extra-judicial tribunals—non-discriminatory domestic policies and government actions that corporations believe violate their new TPP rights and privileges.

The TPP would potentially undermine accountable and democratic governance by imposing binding rules that could not be altered due to consensus of all signatories members. Such rules could threaten a newly elected government with trade sanctions or damages for implementing policies on behalf the public they serve. Furthermore, were the TPP to be implemented, the least economically powerful of the TPP member countries—among them, Vietnam, Malaysia, Chile, and Peru—would have investment, intellectual property, trade, agriculture, procurement, and other policies foreclosed to them.

How could such extreme terms have been negotiated? For the past seven years, the terms of the deal have been a closely guarded secret. Appointed government officials and corporate actors were given more access to the text than elected officials and the public.8 Indeed, in the United States more than 500 official trade advisors—mainly representing corporate interests—had security clearance to access the TPP text and had a special role in formulating the US positions and language for each chapter.

The development and scale of the TPP raises serious questions about how a corporate-driven, heavily privatized, and re-regulated world economy—all of which the deal promotes— would undermine public accountability, thwart democratic mechanisms, and do harm to millions of people whose lives and livelihoods would be impacted.

Our Analysis: Corporate Influence vs. Public Good

The development and scale of the TPP raises serious concerns about how a world economy reregulated to suit corporate interests would undermine public accountability and democratic processes. These concerns prompt us to more fully analyze the context of the TPP agreement and to identify strategies for addressing the concerning trends that the TPP represents. These findings also prompt us to present these concerns to the public, which would be harmed by greater corporate control over the economic rules that have real consequences for peoples’ wellbeing.

The Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society is committed to promoting an inclusive, just, and sustainable society and we do so through conducting engaged research and employing strategic communications to address issues faced by the most marginalized populations. Our research and analysis of the TPP agreement raises serious concerns about the trade deal with respect to the following three principles:

- Democratic Participation. The first among these principles is democratic participation—a response to the TPP’s secrecy from the general public and elected officials, and its relative non-secrecy to corporations and appointed, non-elected government bureaucrats. With regard to such agreements, democratic participation encompasses access to key decision-makers and decision-making processes, and the ability to make meaningful contributions to the decision-making process. A central tenet of this stance is that those who have been historically marginalized from decision-making—from low-income communities and communities of color within the United States, to the most impoverished and vulnerable nations across the world—need to have greater capacity for participation in such processes.

- Transparency.viii The second among these principles is transparency, which is essential for democratic participation. Access to information motivates and empowers the general public to participate in an informed manner. This access to information is vital for holding government agencies and private corporations accountable for decisions that affect the public. Regarding the TPP in particular, transparency is crucial, as every part of society would be affected by this agreement including food safety, healthcare, the environment, migration, and the distribution of wealth, among others.

- Public Accountability. The third among these principles is public accountability, which compels us to question whether public institutions and representatives are accountable to people or to corporations. As part of the system of increasing privatization, which has taken shape since the early 1980s, the overall exercise of political power has been increasingly modeled on principles of the market-based economy. In this way, governments have become more responsive to corporate actors and interests and less to their own people. The case against the TPP must be one that holds democratic institutions and decision-makers accountable to the interests and wellbeing of the general public and not corporations.

Purpose

This report explains how the Trans-Pacific Partnership undermines these key principles. Our analysis of this trade agreement raises serious questions that should be of concern to all who are interested in working towards a free and open society—including local government officials, legal and public interest advocates, labor unions, medical and healthcare workers, environmental advocates, consumer groups, and all social justice advocates more broadly. This report provides an account of the development, scale, scope, and potential implications of the TPP, as well as accounts of ongoing opposition to the agreement. In doing so, this report addresses the ongoing corporatization of US economic, legal, and political systems, of which the TPP is a particularly egregious instantiation.

It is imperative that those interested in fair and equitable public policy are able to have adequate information and informed analyses to engage in the forthcoming US political debate about the TPP and whether it should be approved or rejected by the US Congress. As such, this report also aims to aid in a public response.

Part 1: The History, Scale, and Scope of the TPP

This section outlines the development of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, focusing on the ways in which transparency and democratic participation have been compromised by both corporate power and US foreign policy interests in the formation and negotiation of the agreement.

Trade Agreements, Fast Track, and the Erosion of Congressional Authority

The US Constitution gives exclusive authority over trade to the Congress, while only the executive branch has authority to represent the nation in international negotiations. Thus, negotiation and approval of trade agreements required coordination between the executive and legislative branches—an intentional check and balance created by the Founders. For most of US history, trade agreements were considered to be treaties requiring ratification by a two-thirds vote of the Senate with changes to tariff levels. Throughout the nation’s history, the executive branch has sought increased control over trade, and until recent decades Congress was unwilling to cede its authority.

By 1934, however, the executive branch convinced Congress that it was too burdensome to require a congressional vote on every tariff change. As a result, Congress delegated to the President the authority to cut tariffs on trade in goods and services within certain set bands for certain time periods without requiring Congress to approve the changes or approve a trade agreement. This move prompted changes in how such agreements were established, with elected officials playing a relatively smaller role.

President Nixon moved to consolidate executive branch power over trade. He proposed a much broader delegation of Congress’ constitutional trade authority that would allow him to proclaim changes to US law—not only tariff levels—to comply with trade agreement terms.ix Congress did not go along with the full proposal, but in 1974, Congress passed the Trade Reform Act, which allowed a president to sign and enter into trade agreements that covered more than tariff cuts before Congress voted to approve such terms, and a president to submit legislation to Congress to implement such pacts that would be guaranteed a vote within a set number of days with all committee and floor amendments forbidden and debate limited. Congress then reauthorized the procedure, called “Fast Track” trade authority until it lapsed in 1994.x Congress rejected President Bill Clinton’s effort to reauthorize Fast Track in 1997 and 1998, but it was approved again in 2002, when proponents sought to rename it Trade Promotion Authority (TPA).9

Fast Track is the device used primarily when a president wants to push a trade agreement through Congress when it would not have otherwise made it through via traditional legislative processes.10 Since an epic 1991 Fast Track fight, delegations of the controversial authority have occurred with fierce corporate lobbying efforts.11

At the same time that the role of Congress and the public was reduced by Fast Track, the scope of the agreements began to expand. Starting with a 1988 FTA between the United States and Canada, a broad group of rules were included aimed at eliminating what were dubbed “non-tariff trade barriers”—otherwise known as environmental, food safety, and other regulatory standards. That pact also included rules on procurement, copyrights and patents, and the service sector. Thus, according to David Morris of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, “modern multi-faceted trade pacts have more to do with pre-empting national, state and local rules that could favor communities or regional economies or domestic businesses or the environment.”12 Together, these trends would come to define trade agreements in the latter half of the 20th century.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is thus an over-encompassing trade agreement that has required the executive branch to stretch its power. Even though Fast Track authority had expired in 2007, the US Trade Representative, on behalf of President George W. Bush, notified Congress in September 2008 that he intended to enter into negotiations for what would be known as the “Trans-Pacific Partnership,” as if Fast Track authority still applied. TPP negotiations were within months of completion when, in June of 2015, President Obama’s four-year effort to obtain Fast Track resulted in narrow passage of a new delegation of the authority. Given that a final deal on the over 5000-page agreement would be announced in early November 2015, the absence of democratic participation and transparency in the TPP’s establishment was already a foregone conclusion.

An Agreement Made in Secret

The TPP itself was primarily negotiated in secret and hidden from not only from the general populations of the 12 nations, but also from their elected representatives in their respective legislative branches. Leaders of the TPP member countries kept the full text of the agreement secret until the full package was ready to be released, supposedly fearful—according to proponents—of undercutting their own negotiators. In actuality, the TPP was kept a secret because of the fear that the public becoming aware of the details of the agreement would fuel massive opposition to it.

The TPP text was classified and, until June 2014, not even members of Congress were given access. Even that access was conditioned on additional requirements: members of Congress were not able to bring in non-security cleared staff or any cellular devices; were handed one section of the agreement at a time; were watched over as they read; could not make copies of anything; and, were asked to hand over any notes taken before they left a secure reading room in the basement of the Capitol Visitor Center.13 Until a month after the deal was finalized, the public, press and congressional staff without security clearances were forbidden any access.

In contrast, appointed bureaucrats and hundreds of official US “trade advi - sors” representing corporate interests had access. Many of the US negotia - tors themselves were former corporate attorneys or executives and received financial packages from their former corporate employers before joining the administration as trade advisors.14 For example, United States Trade Repre - sentative Michael Froman, a driving force behind the TPP, received more than $4 million as part of multiple exit payments when he left Citigroup to join the Obama administration. The lead TPP agriculture negotiator previously worked at a trade association representing biotech firms and other USTR officials came from the pharmaceutical and content industries.15 Stefan Selig, a Bank of America investment banker who became the Undersecretary for Internation - al Trade at the Department of Commerce, received more than $9 million in bonus pay when he was nominated to join the Obama administration.16 These are only a few examples of the revolving door between corporations and US government agencies responsible for trade agreement negotiations that results in corporate interests being translated into US economic and foreign policy.17

Public interest advocacy groups, think tanks, and the press have regular - ly called for greater transparency in the process, and have called out the pervasive corporate influence shaping US economic and foreign policy. Despite intensive efforts by the TPP governments to keep the agreement’s text hidden, WikiLeaks published three draft chapters, starting in 2013.18 Until November 5, 2015, a month after the 12 negotiating countries reached an agreement, the remaining 27 chapters of the TPP remained hidden, even though negotiators and corporate actors had been given privileged access. (To circumvent that secrecy and expose the text of the TPP, WikiLeaks launched a campaign to crowdsource a $100,000 reward for the full body of the agreement19 —just before the agreement was finalized in October, almost $114,000 had been pledged.)20

Impact on Public Accountability: Who’s at the Table?

The secrecy of the TPP during the negotiation process was unprecedented, and US legislators responded accordingly. For example, in May 2012, Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) argued that, “the majority of Congress is being kept in the dark as to the substance of the TPP negotia - tions, while representatives of US corporations like Halliburton, Chevron, PHRMA, Comcast, and the Motion Picture Association of America are being consulted and made privy to details of the agreement.”i

In protest of the TPP’s secrecy, Senator Wyden introduced a bill (S.3225) calling for congres - sional oversight over the detail of the TPP negotiations. Though it never gained traction, the bill made requests that members of the Congress should be provided with “access to documents, including classified materials, regarding trade agreement negotiations to which the United States is a party and policies advanced by the USTR to any Member of Con - gress who requests such documents as well as Member staff with proper security clearanc - es.”ii Additionally, in a May 2014 open letter to the Trade Minister Andrew Robb, 46 Australian unions, public health, church groups, and other community organizations called upon the gov - ernment of Australia to reject what they called a “harmful proposal in the TPP which poses unacceptable risks and costs, and should not be traded away in secret negotiations.”iii

The Origins of the TPP and US Influence

The theme of the lack of transparency and equitable participation during the negotiation process of the TPP was also at play among the negotiating parties themselves. The way the TPP was negotiated illustrates how the US dominated the negotiating process, acting in service of its own interests in the Pacific.

The TPP has its roots in the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (TPSEP or P4), a comprehensive agreement between Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore that covered trade in goods, rules of origin, trade remedies, technical barriers to trade, trade in services, intellectual property, government procurement and competition policy.21 The pact included the elimination of all tariffs between member countries by 2015. The TPSEP/P4 had built-in negotiations on the issues they could not agree—namely, investment and financial services. The US joined those sectorial talks in 1998. Only once the US entered did other countries ask to join.

Shortly thereafter, the US took charge of the negotiations, with President Obama reaffirming in November 2009 that the US would engage with the member countries of what would soon be renamed the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The stated goal of doing so was to shape a “regional agreement that will have broad-based membership and the high standards worthy of a 21st century trade agreement.”22 Though the original TPSEP/P4, and the TPP that it would later become, shared many of the same features, the entrance of the US and its centering of its own economic interests under the banner of a “21st century trade agreement” reflected a shifting dynamic in trade among the Pacific nations.

In joining the TPP negotiations and becoming a key mediator for the process, the US took the opportunity to wrest greater concessions from other countries that it held (or desired) bilateral trade agreements with—among them, Chile, Peru, and Malaysia.23 The leading role of the US in the negotiations for an expanded agreement among the Pacific nations raised legitimate fears for Chile and Peru, two South American countries that had prior bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with the US.24 Soon after President Bush announced the intention of the US to join the negotiations in 2008, one Chilean trade official complained that, with an FTA with the US already in place, he could “only expect greater politically and perhaps economically difficult, demands from the Americans in a TPP.”25 Furthermore, as a Chilean economist put it, renegotiation within the TPP of existing commitments on issues such as intellectual property rights, investment and environment—issues that Chile has already made concessions on through an existing FTA with the US—involves for South American countries the risk of “paying twice” in areas of great political sensitivity and which relate to a broad range of public policies.26

Malaysia had been involved in negotiations for a bilateral FTA with the US, which ultimately stalled because of disagreements on some issues. The TPP, in this light, has afforded the US a second opportunity to wrest from Malaysia what it could not secure in bilateral negotiations.27 Such maneuvers are illustrative of longstanding attempts by the US to secure its own interests (influenced as they are by corporate interests) by shaping the terms and conditions of the negotiation process itself.

Scale and Scope: The Largest Trade and Investment Agreement in History

The scale of the TPP is unprecedented. It comprises 40 percent of global economic output while TPP coverage would represent onethird of global trade. Of the TPP’s total GDP—about $27.5 trillion among the original 12 parties—the US accounts for approximately $15.5 trillion, or over 56 percent, thus helping establish the United States’ strategic importance for other TPP parties as the starting point for the negotiations.28 As a “docking” agreement, any country in the region can add themselves to the agreement after the initial 12 member-countries have approved it. New countries could opt in if they agree to meet existing rules, rather than the US Congress or legislative bodies from other TPP countries negotiating new terms appropriate to new joining countries.29 Finally, the TPP, like all modern trade agreements, would have no expiration date.

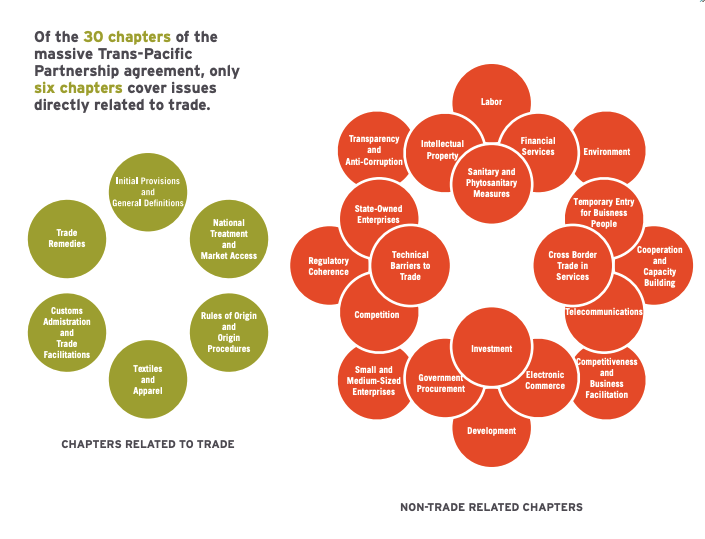

Although it is called a “Free Trade Agreement,” the TPP is not solely, or even primarily, about trade. The scope of the agreement is much broader. As outlined above, the agreement deals with an increasingly broad group of rules called non-tariff trade barriers. For example, of the TPP’s 30 chapters, only 6 chapters deal with traditional trade issuesxi and one chapter would provide incentives to offshore jobs to low-wage countries,xii while many would impose limits on government policies tied to copyrights and patents, labor, product standards, subsidies, health and medicine, environmental standards, and more.30 xiii The scope and reach of the TPP is also unprecedented. For example, the agreement’s rules on tariff and non-tariff trade barriers would be even more stringent than those currently used by the World Trade Organization (i.e., ultimately putting more emphasis on reregulation). As PART II addresses, the policies enacting regulatory, economic, and legal systems of the TPP member countries—from countries with less-developed economies to the US itself—must be conformed to meet the criteria of the agreement.31

Part 2: Implications of the TPP: The Corporations of US Foreign Policy and Erosion of Domestic Protections

Our analysis reveals major implications for public accountability if Congress approves the TPP. This section outlines how the TPP is an extreme example of continued corporatization of US foreign policy and that the deal would not only exacerbate the erosion of public protections, but could also affect the stability of the Asia-Pacific region. Meanwhile, the terms of the TPP set corporations up to benefit the most, with the interests and wellbeing of people faring the worst.

Geopolitical Intentions and Strategies: The TPP and the “Pivot to Asia”

As outlined in PART I, the use of trade and trade agreements by the United States to influence foreign policy has long been the norm. This reality is also apparent in the potential implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Most notable is how the TPP would impact the US’s “Pivot to Asia” strategy and how it could set the stage for major geopolitical implications in the region. Ultimately, despite proponent’s claims of economic growth or job creation, the possible outcomes of the TPP—and its role in the “Pivot to Asia” in particular—do not necessarily serve the interests of American people.

As the center of gravity of US political, economic, and military policy abroad is seen as shifting to the Asia-Pacific region, the TPP can be analyzed as part of that reality.32 By joining economic policy—shaped by corporate interests—with foreign and national security interests in the Asia-Pacific region, the TPP aims to develop partnerships that can be leveraged into geopolitical and military power.33 In a speech in early April 2015, Defense Secretary Ash Carter stressed this aspect of the agreement, stating that, “in terms of our rebalance in the broadest sense,” passage of the TPP is as important as “another aircraft carrier,” and that it would “help us promote a global order that reflects both our interests and our values.”34

The Obama administration’s announcement of a military and diplomatic “pivot” toward Asia points to the continued investment by the US in global leadership. According to a March 2015 paper prepared for members of Congress, “The TPP has potential implications beyond US economic interests in the Asia-Pacific. The region is increasingly seen as being of vital strategic importance to the United States. Throughout the post-World War II period, the region has served as an anchor of US strategic relationships, first in the containment of communism and more recently as a counterweight to the rise of China.”35

In other words, the stated context in which the TPP is being promoted by the United States is to secure dominance in the region in the face of China’s growth. Despite the assertions that are being made by proponents, it is clear that the TPP over-reaches and expands corporate prerogatives in ways that have little to do with China, all the while still securing US dominance in the region as the agent of such corporate prerogatives.

For example, the first way in which the TPP unites corporate prerogatives and military interests with foreign policy is by framing the TPP’s pact as supposedly helping secure trade routes in an increasingly turbulent region. Specifically, China’s territorial ambitions in the regionxiv have seemingly made the US and its regional allies anxious about China’s rise and willingness to project military power, as well as the security of regional trade.37 In May 2015, Secretary Carter clarified the anticipated role of the TPP and stated that the US “will remain the principal security power in the Asia-Pacific for decades to come.”37 Thus, it is under the guise of enforcing freedom of navigation that the agreement may come into play as a major foreign policy “wedge” that secures the interests of the US and its regional allies under the banner of “free trade.”

A major way in which the TPP may uphold US regional and global influence as the agent of corporate interests is by strategically securing Vietnam’s growing economy in a US and Southeast Asia-centric trading bloc that excludes China. Vietnam’s GDP has grown, in part, because of rising wages in China, and because it has had success in attracting the types of low-wage jobs that China aims to move beyond, particularly in sectors such as textiles and low-end assembly.38 Under the banner of facilitating the East Asian development model of export-led growth in manufacturing, proponents of the deal have reported that Vietnam is one of the countries that will supposedly gain the most within the Trans-Pacific Partnership.39 For example, according to the International Trade Administration Office of Textiles and Apparel, in 2015, Vietnam exported roughly $10.5 billion worth of apparel to the United States (12.4 percent of US apparel imports) and roughly $4.3 billion worth of footwear. Under the TPP, Vietnam would be able to export such items to the US at a 0 percent tariff rate, theoretically making Vietnamese exports even more competitive.40

It’s under the guise of enforcing freedom of navigation that the TPP may come into play as a major foreign policy “wedge” that secures the interests of the US and its regional allies under the banner of “free trade.

Despite such justifications for the agreement, were the TPP to be implemented, the least economically powerful of the TPP member countries—among them, Vietnam, Malaysia, Chile, and Peru—would have foreclosed to them investment, intellectual property, trade, agriculture, procurement, and other policies that the rich TPP member countries used to develop their own economies. As Kim Elliott of the Center for Global Development argues, the benefits of the TPP to Vietnam and other clothing exporters would be compromised by the US “yarn forward” rules, which restrict the use of raw materials and textiles from countries outside the agreement—namely, China, a major player in its growing economy.41 Even worse than the issues that arise from the rule of origin are the ways in which Chinese firms, including major state-owned enterprises, are buying up existing Vietnamese production capacity and creating new plants to use Vietnam as an export platform to the US and Japan. Thus, despite the TPP proponents’ push for export-led manufacturing growth, supposedly liberating poor and vulnerable economies, the agreement would instead foreclose particular means of growth while emboldening the US as a key determiner of trade relations in the region.42

Corporate Control and Transnational Power: State-Investor Settlement Disputes and Voluntary Regulations

An alarming reality of the TPP text is that it would significantly expand an international legal and political regime that would allow multinational and transnational corporations to bypass domestic courts and evade public accountability. Additionally, the institutions and mechanisms that corporate actors have used to subvert standard procedures of judicial litigation may themselves be inconsistent with US law, ultimately threatening democratically-elected governments with trade sanctions or cash damages for implementing policies on behalf of the public they serve that do not meet TPP constraints. Principal among these mechanisms invoked within the TPP is the “Investor-State Dispute Settlement” (ISDS), an international arbitration procedure wherein national governments that are member to the particular agreement legally bind themselves to settle “disputes” with “investors” in supra-national tribunals.43 xv Broadly, the tribunals are free standing and ad hoc, with tribunalists coming from a “club” of mainly elite private sector lawyers at firms that specialize in this practice, and that rotate between being arbitrators and using governments.

Various forms of the ISDS arbitration procedure are now a part of almost 2,300 bilateral investment treaties and trade agreements worldwide, of which the United States is party to 50.44 xvi Although there is a wide range of differences in scope and process between each such treaty and agreement, the supra-national tribunal and procedure outlined in the TPP in particular would continue the trend of preferential treatment of corporations.45 For example, if the agreement were to be approved by Congress, the TPP’s ISDS arbitration mechanism would grant foreign investors within TPP member states procedural rights that are not available to domestic firms to “sue” governments outside of national court systems, unconstrained by the rights and obligations of countries’ constitutions, laws and domestic court procedures. The investor can seek compensation from taxpayers not only for actual investments made, but also for the profits that they claim would have been earned where the challenged policy not in place. Significantly, the TPP’s investment protections are extensive and include compensation for “regulatory takings” (in contrast to US law), a guaranteed minimum standard of treatment that extends beyond standard due process rights, free transfer of funds, a ban on performance requirement for foreign investors, and the freedom to appoint people of any nationality to senior management positions, among other protections.

The institutions and mechanisms that corporate actors have used to subvert standard procedures of judicial litigation under democratically-elected governments may well be inconsistent with US law.

Yet, according to an extensive analysis by Public Citizen, the TPP’s investment protections—ostensibly designed to provide foreign investors a means to obtain compensation if a government expropriated their factory or land and the domestic court system did not provide for compensation—are far broader than those provided under any existing Free Trade Agreement to which the various TPP member states are a party.46 For example, by widening the scope of domestic policies and government actions that could be challenged, the TPP would expand US ISDS liability. With Australian, Japanese, and other firms newly empowered to launch ISDS attacks against the United States, the TPP would double US ISDS exposure. More than 1,000 additional corporations in TPP nations, which own more than 9,200 subsidiaries here, could newly launch ISDS cases against the US government, and about 1,300 foreign firms with about 9,500 U.S. subsidiaries are so empowered under all existing US investor-state enforced pacts (most of these are with developing nations with few investors here). Additionally, the TPP would newly empower more than 5,000 U.S. corporations to launch ISDS cases against other signatory governments on behalf of their more than 19,000 subsidiaries in those countries.

At the same time, under pressure from US negotiators, the final text expands the scope of matters that are subject to investor-state enforcement to also include government contracts with foreign investors for natural resource concessions, construction projects and more. According to the analysis by Public Citizen, the final TPP text gives foreign investors greater rights than domestic investors with respect to disputes relating to procurement contracts with the signatory governments, contracts for natural resource concessions on land controlled by the national government and contracts to operate utilities. Finally, the only meaningful new ISDS safeguard or exception included in the final TPP text is a carve-out for tobacco-related public health measures that allows countries to elect to remove such policies from being subject to ISDS challenges, either in advance or once a policy is attacked. Thus, in these and other ways, the TPP unequivocally expands the power of corporations.47

National Policies and Regulations Must Comply with TPP Terms: Labor and Employment, Health and Medicine, and the Environment

The TPP pursues the interests of US foreign policy in such a way that US global leadership is intertwined with and increasingly beholden to the interests of multinational and transnational corporations, while allowing corporations themselves to bypass domestic courts and evade public accountability. Yet, as outlined below, many policies and regulations of the US and other member states of the TPP must comply with TPP terms, and therefore to the corporate interests behind the agreement. There are few protections that the governments and citizenry of TPP member countries can employ when the interests and wellbeing of the public are compromised, despite clearly identified rules codifying benefits for multinational and transnational corporations.48 The principal areas of concern include labor and employment, health and medicine, and the environment and the workers involved in those industries. Specifically, while the TPP includes expansive constraints on government policies to safeguard public health and provide access to affordable medicines, it has weak labor and environmental standards and no rules regarding human rights.

The Impact on Labor: Bad for Working Communities

Many economists warn that if Congress approves the TPP, the US and other member states could see a new austerity regime that could exacerbate existing inequality, and shift more power and wealth from working com - munities to corporations and elites.

Given the threat that a TPP-governed system of global trade and investments would pose to working communities, the presidents of five of the most powerful unions in the US, including the Teamsters, United Steel - workers, Food and Commercial Workers, Machinists, and Communication Workers, issued statements declaring their opposition to the agreement. The leaders framed their opposition in the context of the impact that Free Trade Agreements from the last several decades have had on workers, such as contin - ued deindustrialization and the outsourcing of American manufacturing and service jobs to low-wage countries like Vietnam.i

Labor and Employment

If passed, the TPP would have drastic effects on labor and employment. Among the most significant of such changes for the United States in particular, the TPP would make it far easier for corporations to offshore American jobs. Specifically, the TPP includes investor protections that reduce the costs and risks of relocating production to low-wage countries. Pro-free-trade groups such as the Cato Institute consider such protections a “subsidy” on offshoring, in that these terms lower the risk premium—the return in excess of the risk-free rate of return that an investment is expected to yield—of relocating to venues that American firms might otherwise not consider.49 For example, an initial analysis by labor and public interest experts found that the TPP’s rules of ori - gin would provide further incentives for US companies to outsource produc - tion and offshore jobs, and use countries such Vietnam as export platforms to send their products back to the US.50

Additionally, by facilitating further corporate exploitation of foreign work - ers and increasing downward wage pressure on US workers, the TPP would accelerate the “race to the bottom” spurred by other free trade agreements, such as the NAFTA and CAFTA.51 For example, after NAFTA, US manufac - turing firms fired thousands of US workers and shut down operations in the US and relocated to Mexico in order to take advantage of the low wages and lax restrictions in the country’s “maquiladora” zone.52 The TPP would drive down the wages of US workers by putting them into competition with, for example, Vietnamese workers with abysmal wages. Broadly, a major result of such agreements is that US middle-class wages have remained flat in real terms since the 1970s, despite US worker productivity doubling. Economist now widely name “increased globalization and trade openness” as a key explanation for the unprecedented failure of wages to keep pace with productivity, as noted in recent Federal Reserve Bank research.53 Even economists who defend status-quo trade policies attribute much of the wage-productivity disconnect to a form of “labor arbitrage” that allows multinational firms to continually offshore jobs to lower-wage countries.54 /55

To promise a number of benefits to TPP member countries through privatized trade while not requiring countries to comply with a firm set of labor standards would be a devastating blow for some of the member states’ most marginalized populations, such as low-wage workers, while being a boon for corporate interests.

The TPP also does not strengthen international labor rights protections. A 2014 Government Accountability Office report found that the terms of key labor reforms put into place in May 2007—which are similar to some of those within the TPP—had failed to improve workers’ conditions.56 Further, according to the AFL-CIO, there are extensive, well-documented labor problems in at least four TPP countries (Mexico, Vietnam, Brunei and Malaysia)57 though there is no commitment to requiring all TPP countries to be in full compliance with international labor standards before they receive the supposed benefits of the agreement. Worker rights obligations have never been fully enforced under existing free trade agreements, which have provided a great deal of discretion for worker complaints to be delayed for years or indefinitely.58

Many of the TPP recommendations made by organized labor groups in the US were completely disregarded, particularly those tied to the rights of laborers under international labor conventions. Among such demands was the need to: improve compliance and enforceability, and define the core labor standards, e.g., by referring to International Labor Organization (ILO) Conventions; 59 require that Parties not waive or derogate from any of their labor laws (laws implementing either ILO Core Conventions or acceptable conditions of work), regardless of whether the breach occurred inside or outside of a special zone;60 define “acceptable conditions of work” more broadly to include such concepts as payment of all wages and benefits legally owed and compensation in cases of occupational injuries and illnesses; and increase compliance with labor obligations such as effective labor inspections.61 Rather than incorporate these demands, the TPP fails to set any standards for acceptable conditions of work. To promise a number of “benefits” to TPP member countries through liberalized trade while not requiring countries to comply with a firm set of labor standards would be a devastating blow for some of the member states’ most marginalized populations, such as low-wage workers, and a success for corporate interests.

A separate but related issue is that of public procurement and the promotion of further offshoring of US tax dollars. That is, the TPP and other Free Trade Agreements also undermine the right of nations to set and maintain purchasing preferences that ensure that taxpayer dollars re-circulate domestically.62 For example, during the negotiation process for the TTP’s potential successor, the TTIP, the European Union has been mounting pressure to open public procurement contracts to bids from foreign firms at all levels of government—federal, state and local—thereby treating foreign bidders as if they were local bidders. The TPP already features such a chapter on government procurement (though TPP procurement rules cover only federal procurement) as well as annexes for the US and other member countries, despite the American labor union giant AFL-CIO having urged the omission of that provision. Ultimately, commitments and constraints upon public procurement—which would otherwise be some of the most significant job creation and economic stimulus tools—undermine domestic fiscal policy, and make procurement trade into a private market and not a government tool. Governments should not be required to spend their stimulus funds to create jobs outside of their country, nor should developing countries be prevented from using their funds on domestic stimulus. Rather, governments should be able to use stimulus funds to create jobs at home.63

The Impact on Health: The Cost of Medicine

If approved by Congress, the TPP’s provisions on Intellectual Property (IP) and Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) would undermine existing national laws that provide some protections for generic drug manufacturers and help guarantee the relatively low medicine costs. Groups like Médecins sans Frontières and Oxfam warn, for example, that the agree - ment could threaten the lives of millions of people in developing countries.i As such, in an open letter to the trade ministers, prime minis - ters, and presidents of TPP member countries, key nurse, midwife, and healthcare worker organizations from eight TPP countries voiced strong concerns about the power that the TPP would grant to multinational pharmaceutical manufactures, as well as the role that such manufacturers have had in the negotiation process itself.ii

Health and Medicine

If passed, the TPP could have a substantially negative effect on the health and wellbeing of the population of the US and other TPP member countries, ultimately extending monopoly rights and undermining the potential for affordable health care and medicine. Regarding Intellectual Property (IP), for example, the TPP contains provisions for “soft linkage” between the patent system and US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval process.xvii Under “soft linkage,” according to Public Citizen, a Party must either create a system to provide notice to a “patent holder” (essentially the authorized holder of marketing approval) or allow for notification prior to the marketing of a competing product, or a product for an approved use, claimed under a patent.64 The TPP’s “soft linkage” provisions, though placing restrictions upon manufacturers of generics and biosimilars (products not identical to the original product, unlike generics), are not the worst provisions that the agreement has in store for the health and wellbeing of the population of the US and other TPP member countries.

Particularly devastating among the TPP’s Intellectual Property provisions that extend monopoly rights for corporations and undermine the potential affordable health care and medicine are provisions that ensure marketing exclusivity for biologics. According to Public Citizen, “market exclusivity rules delay generic drug registration for a specified period of time, by limiting the ability of generics manufacturers and regulatory authorities to make use of an originator companies’ data and grant generics marketing approval.” Specifically, such rules allow for “at least five years” of market exclusivity for new pharmaceutical products, where Parties can accept generic medicine applications during those five years, but cannot grant the marketing approval before five years pass from the date of marketing approval in the territory of the Party.65 Ultimately, such measures provide the inventor with a monopoly over the invention for the patent term and have the effect of keep generic competitors off the market.

Ultimately, the TPP gives the food industry a powerful new weapon to wield against the nationwide efforts for affordable health care, safe food, consumer awareness, as well as environmental protections.

Furthermore, according to Public Citizen, marketing exclusivity for new forms and uses of old medicines could be considered a form of “evergreening.” Since marketing exclusivity would apply regardless of the patent status of a drug, even off-patent medicines presented in particular forms and uses outlined by the TPP would not have a generic competitor.66 Among other evergreening rules is the TPP provision requiring all countries to adopt second-use patents that would give another 20-year monopoly to a new use of the same chemical formulation, allowing brand-name companies to re-patent old medicines.

Another damaging provision within the TPP is the mandatory extension of patent terms, also known as “adjustments,” if patent prosecution or drug regulatory reviews exceed a certain period. By delaying market entry for low-cost generic alternatives, longer pharmaceutical patent terms increase cost burdens on patients and government health programs and constrain incremental innovation.67

In these ways, the TPP would ultimately extend monopoly rights and compromise the availability of relatively affordable health care and medicine. For example, generic drugs have saved the US population an estimated $239 billion in 2013 and $1.5 trillion within the past 10 years, yet these and other restrictions would have drastic effects on their costs.68 Considering these provisions, furthermore, it is unsurprising that PhRMA, the lobbying arm of the pharmaceutical industry, is among the top supporters of the TPP.69

In addition to potential impact of the TPP’s Intellectual Property provisions, the health and safety of the general public are compromised by key food safety measures in chapter 7 (Sanitary and Phytosanitary). According to the US Trade Representatives, the chapter aims to give “American farmers and ranchers a fair chance to feed the region’s people; ensure that America’s food supply remains among the safest in the world; and help all TPP partners to better protect the health and safety of their food through modern, science-based food safety regulation.”70 Critics argue, however, that the TPP would allow unsafe food to be imported to the US by allowing new challenges to the US border food safety inspection system not provided for in past trade agreements.71 According to the agreement, border inspections must be “limited to what is reasonable and necessary” and “rationally related to available science,” which, according to Public Citizen, allows challenges to the manner inspections and laboratory tests are conducted.72 According to Food and Water Watch, such provisions mean that agribusiness and biotech companies can now more easily use trade agreements to challenge countries that test for GMO contamination, do not promptly approve new GMO crops or even require GMO labeling, or that ban GMO imports altogether.73

The language in the TPP is far more expansive and powerful than existing trade deals that have already been used to weaken or eliminate country of origin labels, GMO labels, dolphin-safe tuna, and other regulations.74 Ultimately, the TPP gives the food industry a powerful new weapon to wield against the nationwide efforts for affordable health care, safe food, consum - er awareness, as well as environmental protections.

The Impact on Environment and Climate Change: Protecting the Fossil Fuels Economy

The language of environmental protection within the TPP is dangerously vague, has no mention of climate change, and provides no legally biding mechanisms to reduce the social and environmental impacts of extractive fossil fuel-based economies. Instead, the TPP simply calls upon member countries to transition to a low-emissions economy and to “cooperate and engage in capacity-building activities.” As such, many environmental organizations have opposed the TPP on the basis of weak environmental protections and the ability of the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) arbitration mechanism to further relieve corporations of their responsibility to social and environmental wellbeing.

Environmental Protections

The region covered by the TPP faces an array of environmental challeng - es, including illegal logging, wildlife trafficking, illegal fishing, marine pollution, and the effects of global climate change—challenges that would ultimately devastate the environment and threaten human health and the wellbeing of communities. As such, the TPP Environment chapter (Chapter 20) includes “commitments by all TPP Parties to effectively enforce their environmental laws and not to waive or derogate from environmental laws in order to attract trade or investment.”75 Yet, in addition to the fact that such commitments would be enforced through the same dispute settlement pro - cedures and mechanisms available for disputes arising under other chapters of the TPP, there are many other issues with the chapter that undermine international and domestic environmental protections.

Principal among these issues is that the TPP actually erodes some of the in - ternational environmental protections of all US Free Trade Agreements since 2007, particularly with respect to Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs). The TPP limits cooperation on environmental protections among its member states to one MEA—the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora76 —rather than the seven MEAs of other major Free Trade Agreements.77 The chapter is considered to have weak conservation rules and other environmental protections, and is ultimately, according to Naomi Klein, “the latest and largest in a series of international agreements that have attacked working women and men, fueled mindless and carbon-intensive consumption, and prevented governments from enforcing their own regulations to cut greenhouse gas emissions.”78 When addressing fishing and trade in flora and fauna, for example, the TPP merely suggests that (using the loose terminology of the text itself ) member countries “combat” illegal trades, “endeavor” to follow existing measures, and “promote” conservation, thus continuing the trend of excluding provisions that enforce environmental obligations within US-crafted trade agreements.79 Perhaps the most egregious omission is that the TPP makes absolutely no mention of climate change or any international measures to combat it.

The TPP would also greatly erode domestic environmental protections. According to an initial analysis of the TPP that compiled contributions by labor and public interest experts, the TPP would empower foreign fossil fuel corporations to undermine environmental and climate safeguards: “The TPP’s extraordinary rights for foreign corporations virtually replicate those in past pacts that have enabled more than 600 foreign investor challenges to the policies of more than 100 governments, including a moratorium on fracking in Quebec, Canada, a nuclear energy phase-out in Germany, and an environmental panel’s decision to reject a mining project in Nova Scotia, Canada. In one fell swoop, the TPP would roughly double the number of firms that could use this system to challenge US policies.”80 Finally, according to 350.org, the TPP would “greatly enhance the ability for fossil fuel companies to sue local governments that try to resist such extractive industries (e.g., if a province puts a moratorium on fracking) and overrule community resistance (e.g., if a community tries to stop a coal mine).81

Conclusion

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is the latest and perhaps most egregious extension of the corporatization of the US economic, legal, and political system. With political power increasingly modeled on the market-based economy, national governments are selling out the universal representation of the people they serve for the benefit of corporate interests. It is the general public that is left to suffer from such trade and investment agreements, particularly the most marginalized populations. As such, countless communities within the US are mobilizing against the approval of the TPP by Congress, with similar movement across other TPP member countries. Despite it being cloaked in secrecy for over seven years, advocates, scholars, journalists and the public have already begun to clearly see it for what it is—an agreement that puts the interests of corporations before the interests of people.

Our report outlined three major principles that the TPP violates: democratic participation, transparency, and public accountability.

- PART I addressed how democratic participation and transparency have been compromised by both corporate power and US foreign policy during the formation and negotiation of the agreement. Specifically, over the last 40 years, what little democratic participation and transparency there was in trade agreements have all but disappeared, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership is no exception. That the US controlled much of the negotiation process also speaks to how, even among the participating countries, the formation of the agreement was non-democratic.

- PART II addressed some of the major implications of the TPP. It accounted for the TPP’s role as part and parcel of the corporatization of US foreign policy, such as the United States’ concerted “Pivot to Asia.” It also accounted for the TPP’s role in the continued erosion of public protections and policies within the United States and other TPP member countries, including those tied to labor and employment, health and medicine, and the environment. Together, these characteristics of the TPP highlight how public accountability is virtually non-existent within the agreement—in other words, how the United States’ allegiance to multinational corporations trumps any such investment in the wellbeing of its own population or the wellbeing of the populations of the other TPP member countries.

Recommendations

It is imperative that there is public awareness of the terms of the TPP, its implications, and its potential harms. Our analysis urges a deep consideration of the threats to the wellbeing of people in all sectors of society by the TPP agreement. While we have identified important points of the TPP, the reality is that, due to Fast Track, Congress only requires an up or down vote on the TPP, meaning the deal must be accepted or rejected in its entirety—a reality that illustrates the problematic nature of Fast Track itself. In this light, our analysis here raises the following specific three approaches to engage in the forthcoming US political debate about the TPP and whether it should be approved or rejected by the US Congress.

- Question the TPP on ethical terms: As outlined throughout the report, the ethical case against the TPP—an affront to democratic participation, transparency, and public accountability—is a strong one with far-reaching socio-economic implications. The Government Procurement chapter in the TPP, for example, requires national governments to spend stimulus funds to create jobs elsewhere, and prevents such institutions from using their limited funds on stimulus at-home. That is why the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations recommended omitting the Government Procurement chapter from the TPP.82 Locating central pieces of the TPP that undermine public accountability and shift power from communities to corporations, are key to making sure that governments are accountable to their own people and not to corporations.

- Examine the TPP on Constitutional terms: Perhaps the strategy with the greatest potential is that of challenging the TPP in terms of its constitutionality. There are two possible areas where the TPP might be vulnerable:

- The Arbitration Provision: The first weak point is the arbitration provision of the TPP. Specifically, Chapter 9 of the agreement sets out a series of rules and provisions for investor claims and suits, as outlined above.83 In general, the TPP allows investors (which are defined at the beginning of Chapter 9) to bypass federal courts (and therefore US legal protections, potentially) and go directly into arbitration to seek monetary damages. The concern is that, although treaties are considered, under the Constitution, part of the “supreme law of the land,” a trade agreement may or may not be able to assign private arbitrators the judicial function consistent with Article III of the US Constitution. Although the Supreme Court has never ruled on this particular question, there are a number of previous decisions that raise serious doubts about it.84 Additionally, the US Justice Department issued an opinion two decades ago on whether and when arbitration can replace court adjudication. The US government tries to mask these concerns by noting a number of protections, including transparent proceedings and permitting amicus brief submissions.85

- The Standing Doctrine: The second general issue is “Standing,” apparent in the definition of who can bring claims or is a party at the beginning of Chapter 9 of the agreement. Specifically, as outlined in PART II, only investors have standing under the ISDS ar- The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Corporations Before People and Democracy HAAS INSTITUTE FOR A FAIR & INCLUSIVE SOCIETY 28 bitration system (i.e., the ability to bring claims for breaches of certain investment protections to the tribunal), which means that affected people, like workers or the public, can not bring claims for breaches. Significantly, this provision potentially contravenes US Standing Doctrine and is a key weak point for a major part of the agreement.

- Challenge the institutional roots of the TPP: Evan Greer, the Fight for the Future campaign director, perhaps stated it well when he argued that “[a]t this point, the only true course of action, for members of Congress who still believe in democracy, would be to completely defund and do away with the office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR).”86 The USTR is responsible not only for developing and recommending US trade policy to the president, it is also responsible for conducting trade negotiations between the US and other nations, and for coordinating trade policy domestically. Yet, according to Greer, the USTR is “largely responsible for the TPP and its extremist contents,” and is recognized by many as a key part of the revolving door between industry and government. Pinpointing the institutional origins of the TPP in agencies such as the USTR, as well as focusing on corporations with undue control over these government institutions, is key to engaging in the forthcoming US political debate about the TPP and whether it should be approved or rejected by the US Congress.

Ultimately, our findings about the TPP reveal it as the latest iteration of a global trend of political power being modeled almost entirely after the market-based economy, of national governments selling out the interests of the people they serve in order to instead serve the interest of corporations, and an agreement that, if passed, would threaten key democratic principles in the United States and would have harmful effects on the livelihood of huge numbers of people across the world.

- i a b c d In this report, we use the terms “reregulated” and “reregulation” instead of the more common terms “deregulated” and “deregulation” because it is important to note that the TPP is not focused on deregulation. Rather, it is actually a proliferation of a whole new set of regulations and rules, except these rules are written to benefit corporate interests. Additionally, the term deregulation is typically used to connote freedom from government regulation, with the implication that government is doing something that we need to be “free” from. Our analysis of the TPP finds that the terms are actually a reregulation and recalibration of the rules that govern the world economy

- ii a b c Korea, Colombia, Indonesia, and the Philippines have also publicly expressed their countries are considering joining the TPP

- 1“Outlines of TPP,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, n.d., https://ustr.gov/tpp/outlines-of-TPP.

- 2Daniel R. Russel and Xenia Dormandy, “Transatlantic Interests In Asia” (Chatham House, London, January 13, 2014), http://www.state.gov/p/eap/rls/rm/2014/01/219881.htm.

- iii a b While the TPP and TTIP are trade and investment agreements that also include services, the TiSA only covers the service sector. TiSA includes rules on cross border trade in services, service sector investment, and regulatory standards.

- 3“WikiLeaks’ Most Wanted,” WikiLeaks, n.d., https://wikileaks.org/pledge/

- ivThe difference between the two is that transnational corporations are borderless and without any particular “home” country, while multinational corporations have a parent country despite having a unique selling strategy for the countries where it has investments. Use of the term “corporations” in the remainder of this report refers to both such entities.

- vThough the TPP is not primarily about trade (only 6 of its 30 chapters deal explicitly with trade), it is often regarded as such

- 4“Free Trade Agreements,” International Trade Administration, n.d., http://www.trade.gov/fta/.

- 5“Enforcement and Compliance: How We Help Eliminate Foreign Trade Barriers,” Trade Compliance Center, n.d., http://tcc.export.gov/Report_a_Barrier/how-we-workwith-you.asp.

- 6“The Trans-Pacific Partnership,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, accessed December 15, 2015, http://www.ustr.gov/tpp.

- 7Alfred-Maurice de Zayas “TPP ‘fundamentally flawed,’ should be resisted-UN Human Rights Expert, https://dezayasalfredwordpress. com/2016/02/04/tpp-fundamentally-flawed-should-be-resisted-un-human-rights-expert-media-coverage/

- viThis is only part of the issue. Among the larger impacts of the TPP on medicine would be the limiting of bulk purchasing and negotiated pricing of drugs under patent, and extension of exclusivity on biosimilars.

- viiThe TPP would directly control the movement of workers by allowing certain temporary entry visas for workers.

- 8“Wikileaks Releases Final Negotiated Text of TPP Intellectual Property Chapter Exposing Grave Threat to Internet Freedom, Free Speech, Access to Medicine,” Fight for the Future, October 9, 2015, http://tumblr.fightforthefuture.org/post/130815248738/breaking-wikileaks-releases-final-negotiated-text.

- viiiThe TPP forbids release of the draft texts and negotiating notes and background papers for five years after it is implemented or abandoned.

- ixAldo Beckman, “Nixon Turning to Trade as World Power Force,” Chicago Tribune, December 3, 1972, sec. 1; http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1972/12/03/page/3/article/display-ad-457-no-title

- xThere were several Fast Track delegations with modified version of the authority relative to the 1974 version in separate legislation in 1978, 1980, 1984, and 1988

- 9Todd Tucker and Lori Wallach, The Rise and Fall of Fast Track Trade Authority (Washington, D.C.: Public Citizen, 2013).

- 10Ibid.

- 11Ibid.

- 12David Morris, “Treaties, Trade and Government by the People,” The Huffington Post, June 16, 2016, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-morris/treaties-trade-andgovern_b_7588678.html.

- 13Edward-Isaac Dovere, “Extreme Secrecy Eroding Support for Obama’s Trade Pact,” POLITICO, May 4, 2015, http://www.politico.com/story/2015/05/secrecy-eroding-support-for-trade-pact-criticssay-117581.html.

- 14Dave Johnson, “Now We Know Why Huge TPP Trade Deal Is Kept Secret From the Public,” The Huffington Post, March 27, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dave-johnson/now-we-know-whyhuge-tpp_b_6956540.html.

- 15Lee Fang, “Obama Admin’s TPP Trade Officials Received Hefty Bonuses From Big Banks,” Republic Report, February 17, 2014, http://www.republicreport.org/2014/big-banks-tpp/; “TPP Treaty: Intellectual Property Rights Chapter,” WikiLeaks, October 9, 2015, https://wikileaks.org/tpp-ip3/.

- 16Ibid.

- 17Evan Greer, “Fight for the Future Statement on Conclusion of Secret Trans-Pacific Partnership Negotiations,” Fight for the Future, October 5, 2015, http://tumblr.fightforthefuture.org/post/130555120213/fight-for-thefuture-statement-on-conclusion-of.

- 18Secret Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP)_IP Chapter; https://wikileaks.org/tpp/#start

- 19“WikiLeaks Issues Call for $100,000 Bounty on Monster Trade Treaty,” WikiLeaks, June 2, 2015, https://wikileaks.org/WikiLeaks-issues-call-for-100-000.html.

- 20“WikiLeaks’ Most Wanted.”

- 21T. Rajamoorthy, “The Origins and Evolution of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP),” Global Research, November 10, 2013, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-origins-andevolution-of-the-trans-pacific-partnership-tpp/5357495

- 22“TPP Statements and Actions to Date,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, December 2009, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2009/december/tpp-statements-and-actions-date.

- 23Rajamoorthy, “The Origins and Evolution of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).”

- 24Ibid.

- 25Deborah Elms, “From the P4 Agreement to the Trans-Pacific Partnership: Explaining Expansion Interests in the Asia-Pacific Region,” Studies in Trade and Investment (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), 2011), https://ideas.repec.org/h/unt/ecchap/tipub2618_chap8.html; Rajamoorthy, “The Origins and Evolution of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).”

- 26 Sebastián Herreros, “The Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement: A Latin American Perspective,” Text (Santiago: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, October 27, 2014), http://www.cepal.org/en/publications/4332-trans-pacific-strategic-economic-partnership-agreement-latin-american-perspective; Rajamoorthy, T. “The Origins and Evolution of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Nov. 11, 2013, https://www.transcend.org/tms/2013/11/the-origins-and-evolution-of-the-trans-pacific-partnership-tpp/.”

- 27Rajamoorthy, T., “The Origins and Evolution of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP),” Nov. 11, 2013, https://www.transcend.org/tms/2013/11/the-origins-and-evolution-of-the-trans-pacific-partnership-tpp/.

- 28Joshua Meltzer, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, the Environment and Climate Change,” The Brookings Institution, accessed December 15, 2015, http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2013/09/trans-pacific-partnership-meltzer.

- 29Lori Wallach, “TPP Presentation” (Washington Joint Legislative Oversight Committee on Trade Policy, Washington, D.C., November 2012), http://leg.wa.gov/JointCommittees/LOCTP/Documents/2012Nov14/TPP%20Presentation.pdf.

- xiThose chapters are: chapter 1 on Initial Provisions and General definitions, chapter 2 on National Treatment and Market Access, chapter 3 on Rules of Origin and Origin Procedures, chapter 4 on Textiles and Apparel, chapter 5 on Customs Administration and Trade Facilitation, chapter 6 on Trade Remedies. Additionally, non-trade chapters are: chapter 7 on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, chapter 8 on Technical Barriers to Trade, chapter 9 on Investment, chapter 10 on Cross Border Trade in Services, chapter 11 on Financial Services, chapter 12 on Temporary Entry for Business Persons, chapter 13 on Telecommunications, chapter on 14 Electronic Commerce, chapter 15 on Government Procurement, chapter 16 on Competition, chapter 17 on State-Owned Enterprises, chapter 18 on Intellectual Property, chapter 19 on Labour, chapter 20 on Environment, chapter 21 on Cooperation and Capacity Building, chapter 22 on Competitiveness and Business Facilitation, chapter 23 on Development, chapter 24 on Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, chapter 25 on Regulatory Coherence, chapter 26 on Transparency and Anti-Corruption. Finally, the TPP’s standard administrative chapters include: chapter 27 on Administrative and Institutional Provisions, chapter 28 on Dispute Settlement, chapter 29 on Exceptions, and chapter 30 on Final Provisions

- xiipecifically, the TPP’s Investment Chapter provides special benefits to firms that offshore American jobs and removes many of the risks that would otherwise deter firms from moving to low-wage countries. See Public Citizen’s brief analysis of the TPP’s potential role in offshoring and lower wages: http://www.citizen.org/documents/tpp-wages-jobs.pdf

- 30“Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): More Job Offshoring, Lower Wages, Unsafe Food Imports,” Public Citizen, n.d., http://www.citizen.org/TPP.

- xiiiAccording to the Office of the United State Trade Representative, the full list of commercial relations covered by the TPP includes: competition, cooperation and capacity building, cross-border services, customs, e-commerce, environment, financial services, government procurement, intellectual property, investment, labor, legal issues, market access for goods, rules of origin, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, technical barriers to trade, telecommunications, temporary entry, textiles and apparel, trade remedies. See: “Outlines of TPP” published by the Office of the United States Trade Representative. https://ustr.gov/tpp/outlines-of-TPP.

- 31Gabrielle Canon, “Here’s What You Need to Know About the Trade Deal Dividing the Left,” Mother Jones, April 21, 2015, http://www.motherjonescom/mojo/2015/04/trans-pacific-partnership-negotiations-explainer-obama.

- 32Rajamoorthy, “The Origins and Evolution of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)”; Fergusson, McMinimy, and Williams, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Negotiations and Issues for Congress.”

- 33Canon, “Here’s What You Need to Know About the Trade Deal Dividing the Left.”

- 34Ibid.; Ash Carter, “Remarks on the Next Phase of the U.S. Rebalance to the Asia-Pacific (M” (U.S. Department of Defense, April 6, 2015), http://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech-View/Article/606660/remarks-on-thenext-phase-of-the-us-rebalance-tothe-asia-pacific-mccain-instit.

- 35Ian F. Fergusson, Mark McMinimy, and Brock R. Williams, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Negotiations and Issues for Congress” (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, March 20, 2015).

- xivFor example, increasing tensions between Japan and China over a strategically located group of islands, the Senkaku-Diaoyu Islands, in the East China Sea

- 37 a b Stephen Benavides, “How the Trans-Pacific Partnership Is the Core of the U.S. Pivot to China,” Daily Kos, June 1, 2015, http://www.dailykos.com/story/2015/6/1/1389611/-How-theTrans-Pacific-Partnership-is-theCore-of-the-U-S-Pivot-to-China; Collinson, “Obama’s Pivot to Nowhere.”

- 38Alan Beattie, “Export-Led Growth and the False Promise of TPP,” Financial Times, May 28, 2015, http://on.ft.com/1G1uWaU; Steve Johnson, “Vietnam Defies Emerging Market Slowdown,” Financial Times, September 22, 2015, http://on.ft.com/1G14w4d.

- 39Hunter Marston, “What the Trans-Pacific Partnership Means for Southeast Asia,” The Diplomat, July 27, 2015, http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/what-the-transpacific-partnership-means-forsoutheast-asia/; “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment,” Policy Analyses in International Economics (Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute, November 2012)

- 40“TPP: What’s at Stake with the Trade Deal?,” BBC News, April 22, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/business-27107349; Beattie, “Export-Led Growth and the False Promise of TPP,” May 28, 2015.

- 41Dylan Matthews, “Why Obama’s Big Trade Deal Isn’t a No-Brainer for the World’s Poor,” Vox, April 30, 2015, http://www.vox. com/2015/4/30/8517787/tpptrade-global-poor; Alan Beattie, “Export-Led Growth and the False Promise of TPP,” Financial Times, May 28, 2015, http://on.ft.com/1G1uWaU.

- 42Beattie, “Export-Led Growth and the False Promise of TPP,” May 28, 2015.

- 43“Secret Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) - Investment Chapter,” WikiLeaks, October 9, 2015, https://wikileaks.org/tpp-investment/press.html.

- xvWhile the TPP defines “investment” broadly to mean “every asset that an investor owns or controls, directly or indirectly,” it is qualified by a normative criteria that an investment must have “the characteristics of an investment, including such characteristics as the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk”—thus leaving the definition for who can establish a dispute, and under what terms, dangerously broad. See: Tung, Ko-Yung. “Investor-State Dispute Settlement under the Trans-Pacific Partnership.” The California International Law Journal 23, no. 1 (Summer 2015).

- 44“Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS),” Office of the United States Trade Representative, March 2015, https://ustr.gov/aboutus/policy-offices/press-office/fact-sheets/2015/march/investor-state-dispute-settlement-isds.

- xviSpecifically, as of January 1, 2015, the United States has 14 FTAs in force with 20 countries: Australia, Bahrain, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Israel, Jordan, Korea, Mexico, Morocco, Nicaragua, Mexico, Oman, Panama, Peru, and Singapore. The remainders of the ISDS pacts are bilateral investment treaties.

- 45Investor-State Attacks: Empowering Foreign Corporations to Bypass our Courts, Challenge Basic Protections. http://www.citizen.org/investorcases.

- 46Alex Baykitch, Daisy Mallet, and Aleks Sladojevic, “Investor State Dispute Settlement in the TPP,” King & Wood Mallesons, October 9, 2015, http://www.kwm.com/en/au/knowledge/insights/investor-state-dispute-settlement-tpp-isds-20151009.

- 47Lori Wallach, “Secret TPP Investment Chapter Unveiled: It’s Worse than We Thought.” Washington, D.C.: Public Citizen, November 2015..

- 48Pete Dolack, “Now That We Can See the TPP Text, We Know Why It’s Been Kept Secret,” CounterPunch, November 13, 2015, http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/11/13/now-that-we-cansee-the-tpp-text-we-know-why-itsbeen-kept-secret/.