Moving Targets: An Analysis of Global Forced Migration investigates the historical and contemporary causes of forced migration as well as both the challenges and capacities of national and international refugee protections and resettlement efforts.

Written by Othering & Belonging Institute researchers Elsadig Elsheikh and Hossein Ayazi, this report develops a framework of global forced migration that accounts for how experiences of displacement across the globe, and the set of institutional norms and values surrounding “refugeehood,” are inseparable from not only historical and contemporary formations of colonialism, imperialism, and militarization, but also momentary and ongoing environmental changes. It argues that neoliberalization, securitization, and the climate crisis describe these dynamics of global forced migration in the present moment.

The report uses as a starting point what is today commonly referred to as the “European refugee crisis." Despite popular notions that frame the US and Europe as the primary regions impacted by the refugee crisis, the authors illustrate how these areas, with the exception of Sweden and Germany, actually host the fewest refugees relative to their population and wealth—yet have the potential to provide greater support to vulnerable displaced persons and refugees from around the world.

Aimed at advocates, practitioners, policymakers, and researchers, Moving Targets was written to provide a conceptual framework for understanding forced migration, support improvements in local, national, and international refugee policy, and identify research-based interventions to facilitate fairer refugee support mechanisms.

With ten case studies in four “mega-regions” of the world, Moving Targets not only identifies the major dynamics causing massive waves of migration today but also traces the colonial histories of these dynamics and why nations that may seem far removed from the current crises may still have a hand in their creation and exacerbation.

Seeking to envision a set of policy interventions that can not only help establish a more comprehensive and equitable global refugee regime, but also help prevent the future production of refugees, Moving Targets serves as an all-encompassing guide to understanding historical and contemporary dynamics of global forced migration and the obligations of actors at various levels.

Click here to Download a PDF of report. Or find the text version of report below.

Glossary of Terms

ASYLUM SEEKER Individual seeking international protection but whose claims for refugee status has not yet been determined.

CLIMATE CRISIS A term used to describe climate-induced abrupt environmental disasters and slowly occurring environmental changes, as well as the hardship faced by certain communities because of such changes. The climate crisis has disproportionately affected communities in the Global South.

CLIMATE REFUGEE Individual forcibly displaced people by natural disasters, such as typhoons, hurricanes, and tsunamis, as well as long-term environmental changes triggered by rising temperatures, rising sea levels, water shortages, deforestation, and desertification.

COLONIALISM The deliberate extension of a nation’s power and influence over other peoples and lands, including the use of territorial seizure, legal justifications for occupation, regimes of racialization, labor exploitation, and forced assimilation. Such dynamics become the conditions from which more indirect forms of rule, military action, and economic control can be established.

ETHNOCIDE Refers to the erasure of culture, spatial segregations, and the reorganization of social space; and the legal formations that undergird such processes.

FOOD REFUGEE While difficult to separate from climate refugees, food refugees are those who have been forcibly displaced due to growing food insecurity caused by: foreign military intervention, armed conflict, political and civil unrest, and/or environmental challenges, as well as circumstances perpetuated by land grabs, seed monopolies, natural resource grabs, global warming, the increased commodification of food, and structures and arrangements of international free trade agreements.

FORCED MIGRATION The movement of people from their lands or places of origin due to conflict, natural or environmental disasters, famine, or development projects. Conflict-induced displacement occurs when people are forced to flee their homes as a result of armed conflict, generalized violence, and persecution on the grounds of nationality, race, religion, political affiliation, or social group. Development-induced displacement occurs when people are compelled to move as a result of projects implemented to advance development efforts, such as the building of a large-scale infrastructure project. Disaster induced displacement occurs when people are displaced due to natural disasters, environmental change, and human-made disasters.

GLOBAL NORTH, GLOBAL SOUTH These terms do not describe a geographical divide but a social, political, and economic divide between formally colonial and colonized countries, while also accounting for ongoing indirect forms of rule, military measures and encampments, and global economies. The use of the term emphasizes the limitations of other terms such as first world vs. third world, or developed vs. developing countries. Global North comprises the countries of Australia, Europe, Japan, New Zealand, and North America (excluding Mexico). Global South describes the rest of the world and includes countries of Africa, Asia (excluding Japan), Latin America, and other island countries in the Indian and Pacific Ocean.

GLOBAL REFUGEE REGIME The set of norms that define who is a refugee, the rights to which that person is entitled, and the norms that define who is expected to support that person. Within this global refugee regime, refugees officially include individuals recognized under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, persons recognized under the 1969 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, those recognized in accordance with the UNHCR Statute, individuals granted complementary forms of protection, and individuals granted temporary protection, and individuals in refugee-like situations.

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Persons or groups forced to leave their home or place of habitual residence as a result of, or in order to avoid, the effects of armed conflict, situations of violence, violations of human rights, or natural or human-made disasters, yet who have not crossed an international border.

LAND GRABS The acquisition of local, community, or communal land by foreign governments, foreign firms, or local entities, and also the displacement and expulsion of people living and working on that land.

MIGRANT UNESCO defines the term migrant as “any person who lives temporarily or permanently in a country where he or she was not born, and has acquired some significant social ties to this country.” The term migrant should be understood as “covering all cases where the decision to migrate is taken freely by the individual concerned, for reasons of ‘personal convenience’ and without intervention of an external compelling factor.” Although we argue in this report that most migration is forced, this definition indicates that the term migrant differs from refugees in that it does not refer to those forced or compelled to leave their homes.

NEOLIBERALISM/NEOLIBERALIZATION This term refers to the late twentieth century, and still ongoing, reinterpretation and exercise of state and political power modeled on market economy values. Neoliberalism is the extension and dissemination of market economy values to all institutions, displacing or weakening the role of the government and state as the representation of the people. Neoliberalization is the strengthening of dynamics that expel and ecxclude many people from participating in the economy and society.

PALESTINIAN REFUGEES Individuals and their descendants whose residence was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, who lost their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict. Following that war, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) was established by United Nations in 1949, and began operations in 1950, to carry out direct relief and work programs for Palestinian refugees. UNRWA is unique in terms of its long-standing commitment to one group of refugees, and in the absence of any international solution for Palestinian refugees, the General Assembly has repeatedly renewed UNRWA’s mandate, most recently extending it until 30 June 2017.

REFUGEE According to the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), a refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. Most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so.

RETURNEE A returnee, also called voluntary repatriate, is a refugee who returns home. This can only happen when the factors that caused someone to flee are no longer an issue in the country of origin. Returning may take place over a period of time beginning with visits to the home country. Assistance may be needed for legal issues and for reunited returnees and family members.

SECURITIZATION Broadly refers to a state’s “condition of heightened security” and need to strategically manage expulsions,deportations, and resource and power conflicts. These security concerns have taken on a number of forms, such as the proliferation of surveillance technologies, increased military presence and activities on national borders. Securitization is exacerbated by and linked to rhetoric and policies that exacerbate anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment, often leading to the conflation of migrants and those seeking refuge with supposed "terrorists" or those who pose threats to national security.

UNEVENNESS OF FORCED MIGRATION The longstanding and presently exacerbated mass displacement of people from the Global South in particular, the hosting of the vast majority of the forcibly displaced within countries in the Global South, and the reality of how some nations within the Global North have disregarded the terms and norms of international refugee conventions.

Introduction

REPORT OUTLINE

PART 1 addresses the origins and evolution of the global refugee regime—the set of norms that define who is a refugee, the rights to which that person is entitled, and the norms that define who is expected to support that person. It also addresses the support that person has actually received, attending to the significance of their country of origin and intended host country, the cause of their displacement, and the broader social and political context within which their journey has taken place.

PART 2 offers our analysis of the central dynamics of forced migration in the present day—neoliberalization, securitization, and the climate crisis, to explain larger trends in the causes of contemporary forced migration, as well as how responses by the international community operate as triggers and feedback loops for such processes.

PART 3 elaborates upon regional experiences of neoliberalization, securitization, and the climate crisis by offering histories of Asia-Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa. This section highlights the significance of European and US colonial and imperial influence in shaping the politics of these regions and the experience of forced migration patterns in these regions.

Policy Interventions, the last section, concludes the report by laying out practices and policies that can help establish a more equitable and comprehensive framework for identifying, supporting, and humanizing refugees.

THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY has fallen short in fully reckoning with the historical and contemporary dynamics of global forced migration, and creating equitable and sustainable solutions to accommodate millions of forcibly displaced people seeking refuge from war, political instability, and environmental change. In this report, Moving Targets: An Analysis of Global Forced Migration, we interrogate the many social, political, economic, and environmental forces that constitute global forced migration, past and present, as well as how these forces have shaped the realities of millions of displaced peoples around the world.

Moving Targets aims to develop a framework of global forced migration that accounts for how the experiences of displacement across the globe and the set of norms that define who is a refugee, the rights to which that person is entitled, the norms surrounding who is expected to support that person, and the support that person actually receives, are all inseparable from not only historical and contemporary formations of colonialism, imperialism, and militarization, but also momentary and ongoing environmental changes. The framework we seek to develop also accounts for how these dynamics are collectively underpinned by processes of Othering—whether along markers of race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, religion, nationality, geography, or a combination of these dimensions.

The Haas Institute has long believed that the frame of “Othering” provides a critical perspective to our common objective of building a more inclusive and equitable society. It is in the responses to the experiences of displacement across the globe that we seek to counteract such processes, expose the power structures that generate them, and also to find and elevate strains of Belonging—enough, perhaps, to generate hope for a more inclusive world.

As part of this larger framework, Moving Targets aims to:

- Outline the causes of forced migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, from the mass displacement in the World War II era, to the current mass displace- ment of people primarily from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa;

- Recount the origins and evolution of refugee protection mechanisms;

- Account for why displaced peoples largely come from the Global South, why the Global South hosts the vast majority of the displaced, why so many seek long-term refuge in the Global North, and why the response in the Global North has been limited;

- Attend to the different histories and dynamics of forced migration in the Americas, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific;

- Account for the ways in which climate change has shaped the current refugee landscape and forced migration more broadly;

- And envision a set of policy interventions that can not only help establish a more comprehensive and equitable global refugee regime, but also help prevent the future production of refugees.

THE WORLD IS CURRENTLY WITNESSING the largest wave of forced migration seen in nearly a century. In 2015, large numbers of predominately Syrian, Afghan, and Iraqi people who were fleeing war, political instability, and military action captured the attention of the European public, leading to the what began to be commonly described as the "European refugee crisis."

Yet major migratory waves and patterns are happening across the entire globe, and while many are due to violence and instability, those are not the only circumstances leading to displacement. Austerity measures, economic precarity, land dispossession, and, increasingly, environmental disasters due to climate change are also forcing many to migrate.

In this report, we will critically engage with the multiple crises of global forced migration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These crises encompass the many causes and experiences of displacement, as well as the set of norms that define who is a refugee, the rights to which that person is entitled, the norms that define who is expected to support that person, and the support that person actually receives. Our analysis in this report includes:

- The mechanisms that lead to the forcible displacement of people and the various and often problematic responses to the plight of the displaced;

- The colonial past of the Global North, with a focus on Europe and the US in particular;

- The disproportionate burden to house refugees placed upon countries in the Global South due to political resistance and lack of political will from countries within the Global North;

- The social, political, economic, and environmental nature of such dynamics that encompass the various types of displaced peoples, from economic migrants, to asylum seekers, to climate refugees.

After developing a framework for understanding the interrelatedness of the crises of forced migration, we ultimately envision a set of policy interventions that, if enacted, can help establish a more equitable and comprehensive social, political, economic, and legal framework for identifying and supporting refugees.

IN 2015 AN INFLUX OF PEOPLE seeking asylum made the journey to Europe by way of the Aegean Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, and Southeast Europe. Most of these people came from Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia: according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the top three nationalities of the over 1.3 million arrivals by the Mediterranean Sea in 2015 were Syrian (49 percent), Afghan (21 percent), and Iraqi (8 percent), making up 78 percent of all refugees and migrants arriving in Europe by sea that year.

By April of 2015, the plight of these refugees became highly visible to the public when five boats carrying almost 2,000 people fleeing to the European Union sank in the Mediterranean Sea—more than 1,200 people were estimated to have died. By the end of 2015, the total scale of the mass movement had become even clearer: the total number of forcibly displaced people worldwide had reached 63.9 million, the highest level since World War II and the greatest proportion of displaced people to world population since 1951 when the UNHCR began collecting statistics.1 The “crisis” therefore came to signal not only the massive influx of migrants and refugees, but also the inability and lack of desire of European states to swiftly and safely facilitate their intake. The tragic fate that many people, including thousands of children, have experienced on their journey and at Europe’s borders has been the sharpest expression of the “European refugee crisis.”

Yet this crisis also came to illustrate the many crises of forced migration. The first crisis is the dire and longstanding nature of the factors that have forced so many to flee from their homes in countries across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Pacific, and Latin America in the first place. These factors are both internal and external to the countries and regions from which such people have fled, though the two are often difficult to separate. Internal factors include the capture of state institutions by corporate elites, internal civil conflict, extreme indiscriminate acts of violence, and exclusionary political and economic policies.2 External factors include imperial and post-colonial policies and practices from actors largely in the Global North, including military interventions and encampments, to economic and trade policies, to other indirect forms of influence. These have laid the ground for and exacerbated the internal mechanisms of displacement. There are factors that conjoin the myriad social, political, and economic, dynamics, most notably the global climate crisis.3 In their totality, these multiple factors make life unbearable, particularly for those already marginalized.

The second crisis is related to the role that the neighbors of many countries have played in resettling these displaced populations. Those leaving Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, for example, have largely been forced to seek asylum near their home country despite the lack of any sort of guaranteed long-term safety and material wellbeing in those neighboring countries. While media attention has focused on Europe opening or closing its borders to refugees, the impacts of such causes of displacement have been felt far more locally than generally understood. For example, 60 percent of those displaced in recent years were from just five countries, and 77 percent of the world’s Internally Displaced Peoples live in just ten countries, all within the Global South.4

The majority of countries that host the greatest number of refugees are in the Global South and are primarily countries that border the most affected countries. As of 2016, out of the top 10 countries hosting refugees, four are in the Middle East (Turkey, Lebanon, Iran, and Jordan), one is in South Asia (Pakistan), and four are in Africa (Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda).5 Only one European country—Germany—falls within the top ten in terms of numbers of refugees hosted.6

Most of these countries cannot adequately accommodate the refugee populations they are hosting. Smaller countries such as Lebanon and Jordan have up to one quarter of their population comprised of documented refugees. Major constraints are placed on the economies of these countries as refugees are not allowed by law to be employed and therefore have difficulty supporting themselves financially, or are unlicensed to work in the fields or professions they had in their home countries. On the other hand, larger and more prosperous countries, including Brazil, China, Hong Kong, India, Russia, and the US have sufficient financial and human resources to accept large numbers of refugees. In addition, prosperous Gulf Arab states have only accepted a very limited number of refugees over the past several years.

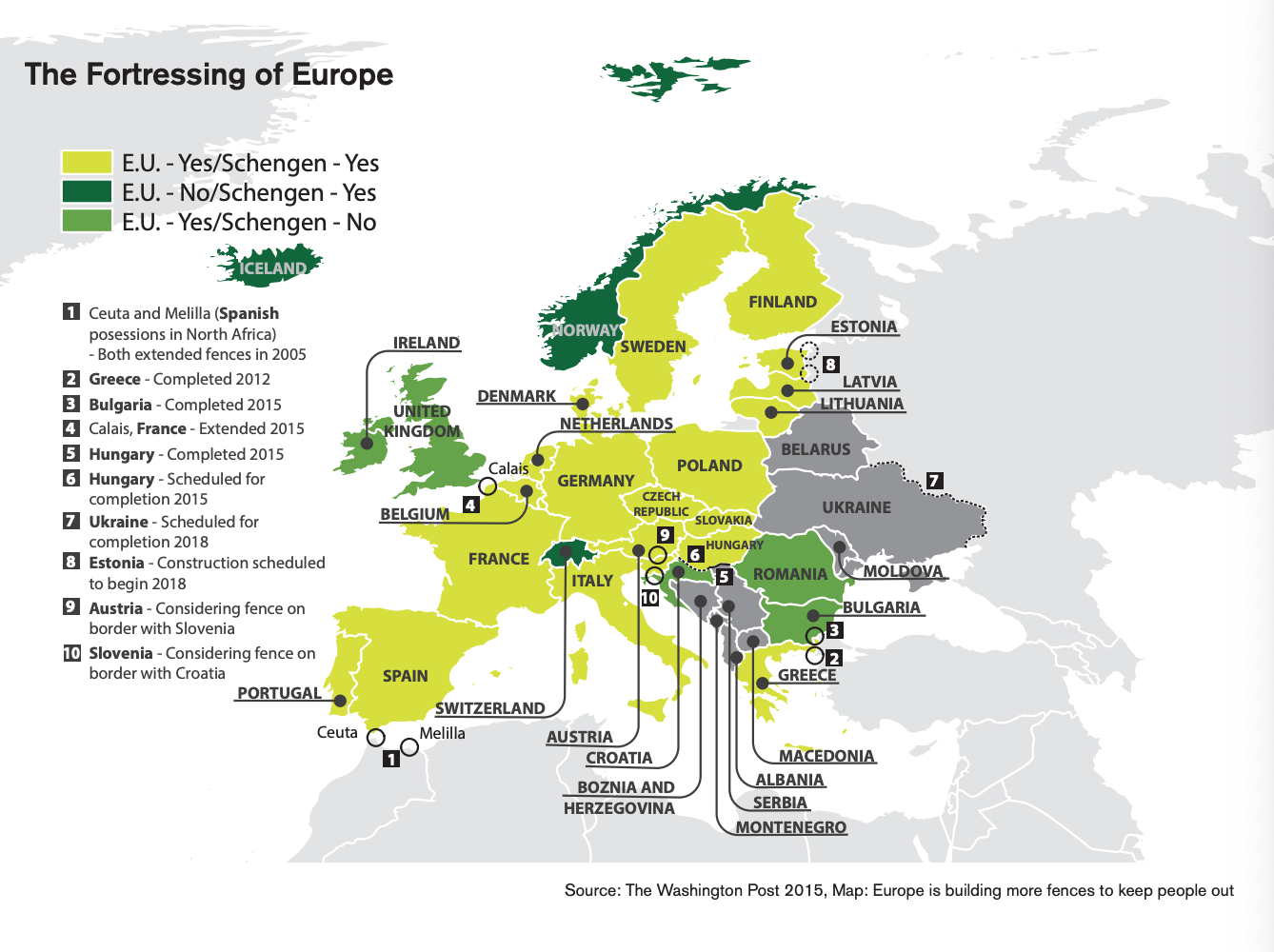

A third crisis is related to the experiences of those seeking refuge in the Global North, many of whom have been met with responses that are far too often neither inclusive nor humane. Across Europe, governments have ignored their obligations to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in order to justify deporting Syrians back to Turkey, a country where most cannot work legally and when deportation back to Syria is a major risk. The Italian, German, and British governments have called for refugees to be returned to Libya, where many migrants work in perilous and inhumane conditions and where conflicts continue. In Greece, Western European leaders have forced the Greek government to detain arriving asylum seekers en route to Germany and elsewhere on the continent, yet have gone back on their promise to move them to such better-resourced countries. In Denmark, asylum seekers have been forced to give up their valuables in order to pay for their stay, and volunteers that have given gifts to them have been prosecuted as smugglers.

These cases are not limited to Europe. In the US, by spring 2016 more than 30 governors refused to accept Muslim refugees.7 In Australia, the decision to turn back many boats full of asylum seekers has been supported by both main political parties, resulting in breaches of international law and tensions with Australia’s neighbors. Despite the thousands of refugees who have officially been accepted by these and others countries, stories and sentiments like these are all too common within the context of the current refugee crisis.

Thus, the current “European refugee crisis” is actually part of a larger set of crises of global forced migration. These range from the crises that have caused the mass displacement of peoples largely from across Africa and Asia, to the crisis of resettlement and the selective and uneven abidance of existing refugee protection mechanisms, particularly within Europe and the US, as well as the climate crisis linked to the droughts and famines that trigger and exacerbate conflict.

Such crises highlight the need for a more holistic approach to understanding forced migration, which necessitates a critical reassessment of the global refugee regime itself—the set of norms that define who is a refugee, the rights to which that person is entitled, and the norms that define who is expected to support that person. Ultimately, this analysis calls for us to envision laws, institutions, and policies that would establish a more equitable and comprehensive response to refugees, so that all those seeking refuge and asylum across the globe are treated with dignity and are afforded belonging.

Part 1: A History of Refugee Protections: Race, Colonialism, and the Unevenness of Forced Migration

In this section we begin our look at forced migration by unpacking the twentieth-century origins and evolution of the global refugee regime: the set of norms that define who is a refugee, the rights to which that person is entitled, and the norms that define who is expected to support that person. We examine the support designated refugees receive, addressing the significance of the person's country of origin, intended host country, the causes of that person's displacement, and the broader social and political context within which their journey has taken place.

Those forced to migrate today are largely from the Global South. Further, the disproportionate burden of accommodating such refugees has also been placed upon the Global South, while many Global North countries have ignored established refugee conventions. These realities illustrate what we call the unevenness of forced migration, which is related to the idea of Europe itself as a "sanctuary"—the relative well-being its populations enjoys, not simply in contrast to regions under former European colonial control, but made possible by way of extractive colonial relations. Our analysis illustrates how these dynamics have been shaped by particular social and political contexts, most notably the Cold War.

World War II and the Origins and Limits of Refugee Protections

With roughly 60 million Europeans fleeing persecution, violence, and poverty during WWII, the extreme vulnerability that characterized the wartime and post-war environment was largely new for Europeans in the modern era.8 As the scale of violence increased, migration continued throughout the war. By 1951, more than five years after the fighting stopped, a million people had yet to find a place to settle.

The Second World War highlighted for many people the ways in which national governments were themselves the cause of the refugee problem. From their origin during the Enlightenment, so-called “human rights” were understood as the rights of national citizens. Yet by the late 1930s, the fact that one’s rights were only as good as the politics of the country they lived in had become apparent9 —for those not under the protection of the racist, homophobic, and ableist ideologies of Germany, for example, this point was quite clear.10

In the wake of WWII, such judicial and political vulnerability motivated the creation of a new universal human rights regime. This included the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 and the Refugee Conventions that followed (in 1951, 1954 and 1961).11 It also included the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.12

A significant major stipulation of the 1951 Refugee Convention was that it was limited to protecting European WWII refugees from only before January 1, 1951.14 Although the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees removed both the temporal and geographic restrictions of the 1951 Refugee Convention, the Protocol gave those states that had previously ratified the 1951 Convention the option to uphold such restrictions.

Given these early Eurocentric limits of international refugee law, for many Europeans WWII was a divergence from the histories of violence that were typically reserved for those areas outside Europe. The war reflected the inward movement of US and European-driven colonial violence and dispossession, racialized expropriations of many kinds, and policies that had virtually ensured that colonized countries across the world would be unable to provide social and economic security for the vast majority of their populations. '

What separates the conditions of World War I from those of World War II are the exclusionary nationalistic and discriminatory ideologies that drove not only mass violence but also the enactment of such violence along new lines of human difference previously experienced primarily by colonized populations. The genocides carried out during World War I, for example, were largely carried out by the Ottoman Empire against Armenians, Assyrians, Lebanese, Kurds, and others, whereas those carried out in World War II were against those people who were part of their respective national populations.

According to the author Hannah Arendt, what the world witnessed during WWII was the experience of violence, death, and displacement by the “civilized” people of Europe that had been previously reserved for the “savages” of the colonial world.15 In the particular tactics used, and within the social and political formations that arose, such links are apparent. According to the African philosopher and political theorist Achille Mbembe, there is a link between national-socialism and traditional imperialism, and as the prominent Martiniquan poet Aimé Césaire stated, fascism is not an aberration in the history of the West, for its brutal tactics and ideas have long been the work of Western empire outside its borders.16 The surprise to Europeans that Europe itself could experience dispossession and violence generally reserved for the colonial world— and, for Europe’s working classes and newly “stateless people” who were themselves compared to the “savages” of the colonial world—speaks to the histories that have created Europe as a place of relative material comfort and supposed “sanctuary” in the world.17 Specifically, territorial acquisition, enslavement and indentured labor, and extractive trade in the colonial world founded the formative wealth of Europe, the US, and elsewhere.18

Violent and extractive colonial relations were sustained so that life within the US and Europe could remain more secure and prosperous. This certain comfort was thrown into question with the rise of authoritarian and far rightwing regimes in Europe—as well as the experience of US blacks in and outside of the Jim Crow-era US South—with violence and displacement taking place on a scale not seen before.

CATEGORIES OF FORCED MIGRATION

International legal mechanisms, some of which are codified in domestic law and others that are generally accepted principles, define various types of people who have been forced from their homes, lands of origin or current place of residence. Here are the most commonly accepted categories of forced migration.

Asylum Seeker is the general term used for people seeking protection in a country different from their country of origin.

Refugee falls within a subset of “asylum seeker”. The basic definition of refugee found in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees is as follows:

"Owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it."

This definition expanded in the 1950 Statute of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees by including persecution on the basis of social group. The 1967 Protocol amended the refugee definition by eliminating geographical and temporal limitations. The EU and Canada have ratified the Convention and Protocol, the US has only ratified the Protocol. In the US, the 1980 Refugee Act defines a refugee as the following:

"(A) any person who is outside any country of such person’s nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable or unwilling to return to, and is unable or unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion, or (B) in such special circumstances as the President after appropriate consultation...may specify, any person who is within the country of such person’s nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, within the country in which such person is habitually residing, and who is persecuted or who has a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion."

International conventions and domestic legislation require a person to be outside their country of origin to be considered a refugee. In contrast, an internally displaced person (IDP) is an individual who remains within their country’s territorial boundaries. The UNCHR Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement define IDPs as:

"persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized border."

Even if IDPs have fled their homes for reasons identical to refugees, they remain under the legal protection of their own government, even if that government is the root cause of their fleeing. IDPs and refugees are subject to the privileges and responsibilities associated with their countries of origin or where they have taken refuge.

There is also a special designated status for those considered stateless. The 1954 Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons defines such a person as someone

“who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law.” Some people are born stateless while others become so later in their lives.

Climate refugee is a term we use for people who are not considered refugees or IDPs, but have been forced to migrate for reasons related to climate change-induced environmental disasters and degradation. The Cancun Adaptation Framework agreed to at the 2010 UN Climate Change Conference called on parties to enhance their understanding and cooperation of “climate-induced displacement, migration and planned relocation.” The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction estimates that more than 19.3 million were displaced by disasters in 2014.

There is also development-induced displacement, another type of forced migration related to the forcing of people out of their homes for economic development such as the building of dams for hydroelectric power and irrigation purposes, mining, creating military installation, airports, industrial plants, weapon testing grounds, railways, road developments, urbanization, conservation projects and forestry, among others. The World Bank estimates that approximately 10 million people are displaced yearly worldwide due to infrastructure programs.13

The Cold War and the Political Utility of Refugee Protections

uropean countries and the US have not always turned their back on migrants and refugees from the Global South (nor do they do so entirely now). Yet during the Cold War, Europe and the United States’ selective acceptance of refugees—dependent upon the country of origin, the receiving country, the cause for displacement, and the social and political context at the time—spoke to how acceptance of refugees has been at times more a matter of political utility than a fundamental belief that such protections should be afforded to all peoples.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the limits of signatories to fully abide by refugee conventions—limits inherent to the origins of such conventions—became especially apparent.

During the Cold War years, the granting of refugee status and protections to asylum seekers became a moral and political tactic. Doing so helped differentiate between the supposed “civilized West” and “uncivilized East”—namely, the Soviet Union.21 As such, the paradigmatic refugee during the Cold War was the Eastern European and Soviet escapee, and the term “refugee” became interchangeable with “defector.” In this way, providing asylum to refugees fleeing communism, who were themselves symbols of communism’s failure, became a foreign policy tool for the US, providing an alleged advantage over the Soviet Union.22 For example, in 1948, following the admission of more than 250,000 displaced Europeans, Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act, which enabled the admission of an additional 400,000 refugees, the vast majority of whom were escaping from Communist governments—namely, Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, Korea, Vietnam, China, and Cuba. Despite conflict not being limited to these selected countries, until the mid-1980s, more than 90 percent of the refugees that the US admitted came primarily from countries in the communist Eastern bloc.23

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the political utility of accepting refugees was severely diminished. It was at this time that the racial and colonial limits of refugee conventions became particularly apparent. During the 1990s there were several prominent refugee emergencies that highlighted not only the shifting geographies of mass displacement but also the negative rhetoric toward about refugees from outside Europe, and the extreme social and political hesitation to accept them. The Kurdish refugee crisis in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War, the displacement resulting from the Balkan wars, the mass exodus resulting from the Rwandan genocide, the waves of refugees from the Horn of Africa and West Africa—all were emergencies that received far less attention than explicitly Cold War crises.24

There was no shortage of stated reasons for refusing to accept non-European refugees. Sadako Ogata, the former UN High Commissioner for Refugees in the 1990s noted that the nature of the refugee crisis was seemingly beyond what the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) could handle.25 Many of the challenges confronted by the agency during the 1990s had political origins and therefore required more than simply humanitarian responses. As such, Ogata has rightly portrayed the nineties as a decade of refugee emergencies. During Ogata’s tenure the average duration of a refugee's situation almost doubled, rising from an average of nine years in 1991 to 17 years by 2003. The decade gave rise to protracted refugee situations, what might be considered the greatest challenge faced in regard to the global refugee protection regime, and forcing the UNHCR to address situations that were seemingly beyond their capacity or mandate to resolve.26 Under such circumstances, Ogata argued that the UNHCR was forced to compromise on a number of its core principles, such as the return of rejected asylum seekers to their place of origin.27

Yet the UNHCR was largely left alone to confront such difficulties during the decade in part because state actors were increasingly unwilling to take action. For example, in Hungary the rise of Victor Orban and his rightwing populist party swept to victory (in 2010 and again in 2014) on the back of xenophobia, Islamophobia, anti-refugee sentiment, and a “keep Europe Christian” platform.28 Hungary’s role in dealing with refugees attempting to get in Europe has been uniquely egregious in its lack of humanitarian response, with in-country asylum-seekers detained, and their applications rejected based largely on their national origin and religion. Amnesty International has documented that “Hungary continued to severely restrict access to the country for refugees and asylum-seekers, criminalizing thousands of people for irregular entry across the border fences put up at its southern border.”29 When Hungary suspended its obligation and refused to accept asylum-seekers other European governments publicly accused the Hungarian government of treating refugees “worse than wild animals.”30

Such anti-refugee sentiment and policy has been at the center of many rightwing European political parties’ push for the formation of more restrictive asylum and refugee policies, and have led many European governments either to inaction or to openly bending under pressure in order to avoid the fulfillment of their international obligations toward refugees.31 These trends pose a fundamental challenge to the rights and support guaranteed within the global refugee regime.

THE EU-TURKEY DEAL: A DECEITFUL AGREEMENT

Changes in international refugee governance are already being made. For example, the EU-Turkey refugee deal, which went into effect March 20, 2016, has been claimed a major victory for the Turkish and German government given its potential to reduce the flow of asylum-seekers into the EU and calm the ongoing refugee crisis. The deal stipulates that: Turkey will work to prevent departures of migrants from Turkey to the EU; in coordination with EU member states, Turkey will return those migrants considered to not be in need of international protection to their country of origin; Turkey will send one Syrian refugee to the EU for every Syrian refugee deported to Turkey; and that Turkey will receive 3–6 billion Euros to aid its own resettlement programs and a promise of easing visa restrictions for Turkish citizens to the EU. In return for Turkey’s agreement, the deal stipulates that the EU would grant visa-free travel to Turkish citizens, accelerate Ankara’s EU membership application, and increase financial aid to help Turkey manage the refugee crisis.

Yet such developments in international refugee governance need be assessed for their larger impacts and precedents they set. The EU-Turkey deal, for example, has introduced a host of new crises: it is arguably illegal under EU law and international law, and it ultimately reflects an entirely wrong framework for new partnerships and measures designed to curb the influx of refugees and adequately process those that do arrive. Despite the stipulations above, for example, only 2,935 Syrian refugees have been resettled to EU member states as of January 17, 2017, while Turkey hosts some 2.8 million Syrian refugees. Additionally, Turkey has not proven to be a safe place for refugees, as many Syrians fleeing violent conflict have been deported from Turkey back to Syria. The borders to other European countries have been closed and are increasingly militarized and securitized, thus creating a bottleneck for all migration to Europe and putting great stress on Greece in particular. Furthermore, as these borders close, other, more precarious paths for human smuggling emerge, leaving refugees with little choice but to make even more perilous journeys across highly surveilled borders. A recent report from Amnesty International calls the EU-Turkey deal “A Blueprint for Despair.

The deal has also nearly frozen the legal process for asylum in Greece. As of March 16, 2017, only around 10,000 asylum seekers were relocated from Greece to another EU member state, out of an initial target of 63,000. Further, since the EU-Turkey deal went into effect, nearly 14,000 asylum seekers have been stuck indefinitely on the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, in prison-like camps that offer little safety or protection, and no clear answers or certainty as to whether their cases will be considered or processed. People fear deportation, which would be a death sentence for the many Syrians who face great risk if sent back to Turkey. Many of the different groups fighting in Syria have extended networks into Turkey, where kidnappings by Syrian regime forces, Jabhat al Nusra, and Daesh have previously occurred. The endless uncertainty and fear of what is to come is the hardest to endure, especially when conditions within the camps continue to worsen.

The camps in Greece are being turned into detention centers, or “hotspots,” complete with fences and barbed wire. There are also plans to build new camps in remote locations that would be completely closed off. Essentially, these refugees are imprisoned with little access to or contact with the outside world. With little access to basic services for physical and mental health, as well as legal needs, the conditions in the camps themselves are abysmal and have continued to worsen.

Such conditions in the camps are essentially a symptom of a deal that is fundamentally flawed. While the world is witnessing the greatest displacement of peoples since WWII, the EU has failed in its responsibility to provide safety and protection for a fraction of the world’s displaced peoples. Instead, it has worked to build walls, borders, and legal regimes to keep people out, in effect, relapsing to a historical period it vowed never to repeat.

Expansion and Contraction of Refugee Protections in the Twenty-first Century

In recent years, however, some progress has been made toward less restrictive asylum policies, and the definition for refugee status has been broadening in some ways under customary international law. According to international law scholar Donald Worster, this is taking place in a few key ways. First, the classification of social group membership appears to be broadening as a result of cultural changes.32 Additionally, some states have begun to recognize non-state actors as potential sources of persecution, rather than only states themselves.33 Finally, the infrequent use of certain exceptions to refugee conventions is also a sign of its broad applicability and dynamic nature.34

At the same time, however, persons and situations covered by customary international law have been contracting.35 For example, internal flight or relocation within the state of nationality has been used as an alternative to seeking official refugee status, as relocation within the state of nationality can seemingly allow for the individual not to face the danger needed for refugee qualification. Additionally, states have applied “safe third country” and “safe country of origin” guidelines—blanket definitions of country’s safety for the purpose of asylum. The recent addition of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia to Germany’s “safe country of origin” list seemingly enables Germany to refuse claims without further review.36

On the one hand, states appear to believe in a humanitarian imperative to protect individuals who are seeking refuge—a seeming shift from the restrictive politics of refugee protections in the wake of the Cold War—while, on the other hand, they are reluctant to permit entry to all those persons falling under their responsibility.37

Even for those who are resettled, the failure to grant citizenship has both contributed to displacement and made it more difficult to resolve. Many states limit the number of viable paths to citizenship. Restrictive framings of national citizenship limit and inhibit local integration. Further, policies that focus on extended detentions in isolated areas—currently highly visible in the practices of Australia, Greece, Turkey, and elsewhere—further undermine efforts of integration. Ultimately, such policies create “separate but equal” systems within the countries where they are seeking asylum. Many refugees can only live in a limited geographic space and are deprived of freedom of movement and protections of the state.38 The International Refugee Rights Initiative states that the proper realization of citizenship is a key factor that determines whether or not a particular person or group will be further displaced; whether they will be able to repatriate; whether they will be accepted by those in their home communities if they do return; how they are perceived in exile both by host communities and those “at home”; whether durable solutions are possible; or whether they will end their lives in exile.39

Taken together, the contracting of those who would be covered by international law and the limiting of pathways to citizenship, despite the seemingly expanding scope of refugee protections, together with the increase of political animosity toward displaced peoples from outside Europe, are trends that we attribute in part to the racialized limits of refugee protections, which have deep roots in the Global North’s history of colonialism. This is not to say that international refugee protections and actions by state actors have not been paramount in providing the possibility for another life for displaced peoples; rather, such protections by international actors have not been as sufficient as should be when the potential political gains were unclear.44

As such, the UNHCR has stated that “the rate at which solutions are being found for refugees and internally displaced people has been on a falling trend since the end of the Cold War.45 This trend is apparent in the treatment of asylum-seekers and other displaced peoples who are part of the current extremity that refugees face, treatment that stands apart from the refugee crises of the past. This treatment includes the mass deportation of Syrians back to Turkey, the call by British, German, and Italian governments for refugees to be sent back to Libya, the Danish government’s demands that asylum seekers hand over valuables to pay for their stay, as well as the stranding of more than 53,000 refugees and migrants in Greece as of April 2016.46

Part 2: Dynamics and Colonial History of Contemporary Forced Migration

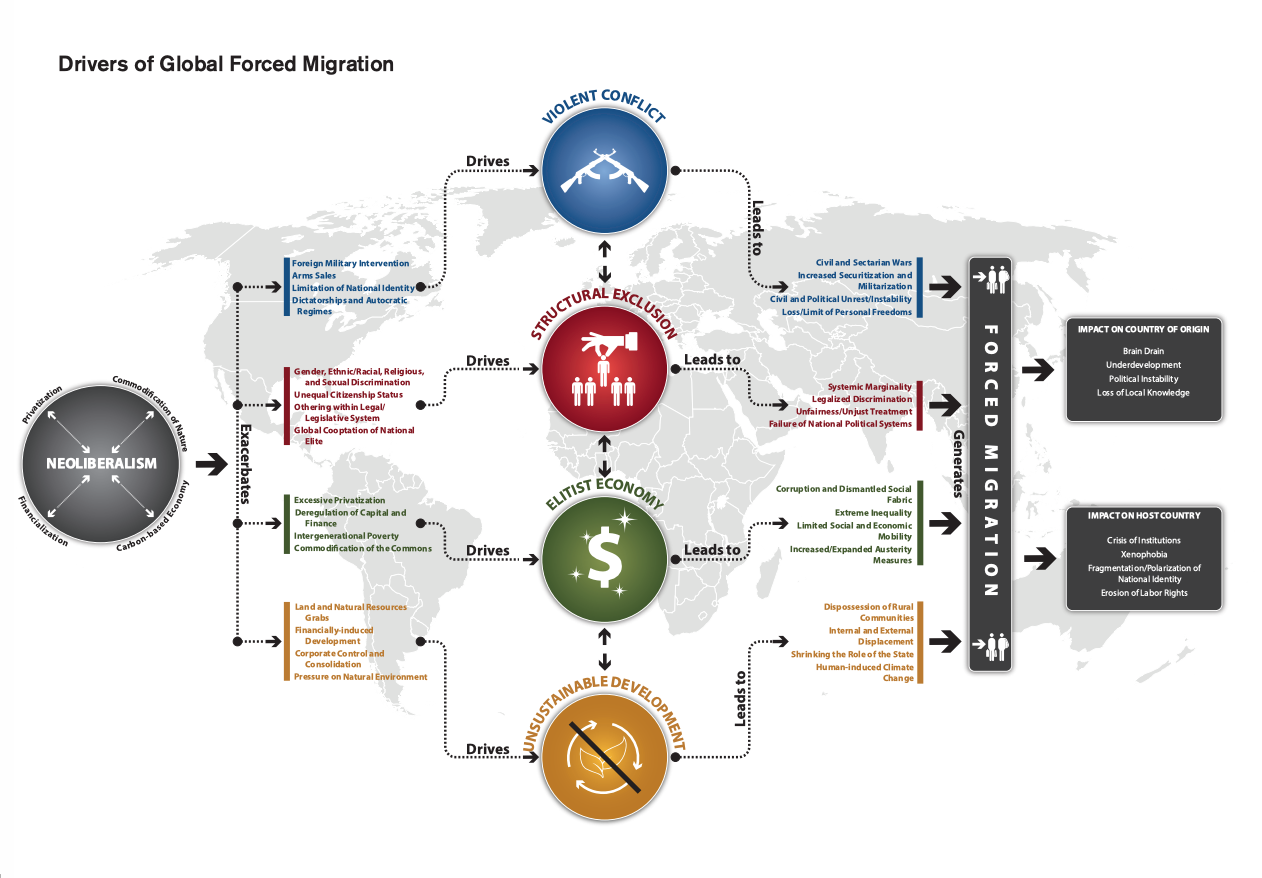

In this section, we extend our analysis of the unevenness of forced migration into the late twentieth century and early twenty-first century. We offer three central dynamics of forced migration in the present day: neoliberalization, securitization, and the climate crisis. These dynamics build upon colonial and imperial histories. Neoliberalization enacts and extends colonial histories of accumulation; securitization enacts and extends colonial histories of militarization; and the climate crisis operates as a trigger and feedback loop and is greatly exacerbated by neoliberalization and securitization. These particular dynamics structure not only the mass displacement of people from the Global South,47 they also structure the anti-refugee and xenophobic response and sentiment in the Global North.

Dynamic 1: Neoliberalization

The first dynamic of global forced migration is neoliberalization. A term often used but rarely defined, neoliberalism or neoliberalization is the late twentieth century reinterpretation and exercise of state and political power modeled on market-based economy values. Political theorist and scholar Wendy Brown describes neoliberalism as the extension and dissemination of market economy values to all institutions and social action, causing the state to further lose its role as the supposed universal representation of people.48 Sociologist Saskia Sassen furthers this analysis by describing how neoliberalization strengthens the particular dynamics that expel people from the economy and from society, dynamics that are now hardwired into the normal functioning of these spheres.49

The historical and institutional rupture in global political economics and governance known as neoliberalism has changed the cause, form, and management of forced migration around the world. Neoliberalism has fomented the further erosion of state support and protections afforded by citizenship within both the Global South and Global North, leading to expulsions of various people within each region. Although a new phenomenon in some ways, neoliberalization has historical roots in the colonial systems of appropriation, expropriation, exploitation, and expulsion.

DIFFERENCES IN NEOLIBERALISM IN THE GLOBAL NORTH AND GLOBAL SOUTH

While it is a global phenomenon, neoliberalization since the 1970s has affected the Global North and the Global South in different ways. As David Lloyd and Patrick Wolfe argue, in the Global North, neoliberalism has manifested in the register of austerity—cuts to, and the privatization of, state-furnished public services, from public utilities, education, healthcare, to social welfare, public space, and other services. This new mode of accumulation reflects the “enclosure” of those public goods historically wrested from the state by social movements during much of the twentieth century—public goods that were fundamental elements of the welfare state itself. To the neoliberal state, according to Lloyd and Wolfe, these public goods “represent vast storehouses of capital, resources, services, and infrastructure” but are now targeted for expropriation and exploitation.50

The outcomes of this enclosure for the general public within the Global North have been far reaching. As Sassen argues, unemployment, out-migration, foreclosures, poverty, imprisonment, and higher suicide rates have become central outcomes of neoliberalism in countries within the Global North. These outcomes can be understood as their own displacements of sorts: displacement from ones’ home and neighborhood vis-à-vis the foreclosure and real estate crises of the 2000s, and from society more broadly vis-à-vis the exponential growth of the prison population in recent decades.51

While many parts of the Global North have experienced austerity measures, the Global South has experienced its own version of neoliberal policies. According to Sassen, the imposition of debt repayment priorities and the opening of markets to powerful foreign firms weakened states throughout the Global South. Such measures ultimately impoverished the middle class and undermined local manufacturing, which could not compete with large mass-market foreign firms.52 These acquisitions were made possible by the explicit goals and unintended outcomes of the IMF and World Bank restructuring programs implemented in much of the Global South in the 1970s, as well as the demands of the World Trade Organization (WTO) from its inception in the 1990s and onward. Sassen argues the resulting mix of constraints and demands “had the effect of disciplining governments not yet fully integrated into the regime of free trade and open borders, and led to sharp shrinkage in government funds for education, health, and infrastructure.”53

There have been many consequences of neoliberalism in the Global South. Principal among them is the exacerbation of resource and power conflicts, which have often taken the form of war, disease, and famine. These have been proximate causes for displacement.54 In other words, the disciplining of countries within the Global South by way of the programs from the 1970s onward is part of the backdrop of the socioeconomic hardships facing many such nations, and, by extension, the current crises of forced migration within and from the Global South.

THE COLONIAL AND IMPERIAL ROOTS OF NEOLIBERALIZATION

Restructuring as experienced in the Global North, which has been primarily in the form of austerity, extends such neoliberal forms of accumulation that the Global South has been subjected to in recent decades. The debt regimes imposed on the Global South are an antecedent to what has begun to take place in the Global North by way of state deficits that have risen sharply in recent years.55

Even further, neoliberalism extends forms of commodification that the Global South has been subjected to long before the 1970s—a reminder that the history of the Global South does not begin with the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization. Specifically, according to Lisa Lowe, “in light of the commodification of human life within slavery, colonialism, as well as contemporary globalization, we can appreciate that what is currently theorized as the financialization of life as 'human capital' in neoliberalism brutally and routinely occurred and continues to occur throughout the course of modern empires.”56 In this way, neoliberalization can be seen as an expansion of those forms of accumulation and expulsions historically associated with racial and colonial difference itself.

Yet the colonial antecedents of neoliberalism are not limited to the Global North’s histories of colonialism that have taken shape outside its own borders. Such antecedents also include the territorial acquisitions that constitute the US, Canada, and other settler colonial states as such. As Lloyd and Wolfe suggest, the fundamental continuity between past formations of settler colonialism and the present-day development of the neoliberal world order “resides in the exigencies of managing surplus populations.”57

Dynamic 2: Securitization

As part of the project of neoliberalism, the role of the state has been redrawn to furnish a conduit for the more rapid distribution of what were once “public goods” into the hands of corporations.58 And in the Global South, alongside the imposition of debt regimes, neoliberalism has forced countless people to be ejected from their homes, communities, and countries. Along with these expulsions, such demands placed upon the state have also fostered a “condition of heightened security.”59 In other words, neoliberalism has taken shape not only in the register of austerity in the Global North and debt regimes in the Global South, but also brought with it the dynamic of securitization. We refer to securitization as the states’ need to strategically manage resource and power conflicts, as well as the manifold displacements, caused by neoliberalism itself.

AUSTERITY, DEBT, AND SECURITIZATION

Examples of the pairing of neoliberalism’s austerity and debt regimes, and new security concerns and measures to deal with the fallout of such regimes, are abound in the US and Europe. According to the Centre for Urban Research on Austerity, examples include:

- Greece’s financial crisis and the disputes regarding polices pushed for from the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (these three entities are the main decision-makers for European Union policy and are commonly referred to as the Troika), alongside what Human Rights Watch has described as the growing crisis of xenophobic violence towards immigrants and political refugees across the country;

- The British austerity narrative promoted by the Conservatives alongside policies and bills preventing terrorism, such as the Government’s Draft Investigatory Power Bill;

- The growing use of force by state actors (e.g., housing eviction officers) and growing control of citizen participation initiatives (e.g., neighborhood renewal partnerships in the UK and the US, or citizen security programs across Latin America where police are a key partner).60

Each of these highlight how Global North austerity and debt regimes are linked with emerging security concerns. Yet given the current increase in forced migrations globally, and the increase in arrivals from the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa in particular, these security concerns within the US and Europe have taken on particularly troubling forms: the anti-immigrant sentiment that conflates migrants, whether driven by economic or political failures, with “terrorist enemies” and other threats to national security; the militarizing of national borders in the name of security; as the proliferation of surveillance technologies; as “ethnocidal” spatial segregations and reorganization of social space; and the legal formations that undergird the dispossession and expropriation of asylum-seekers and economic migrants in particular, and the general population more broadly.61 For example, coinciding with global regimes of austerity and debt has been the so-called global war on terror, which has been used to legitimate an inordinate increase in the development of surveillance technologies and the use of such technologies against the citizenry within the Global North, and has taken the shape of military, political, and surveillance measures against both terrorist organizations and the regimes accused of supporting them in the Global South.62 Yet such links between neoliberalization and securitization can also take on a less explicitly militaristic tone. For example, the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis and the 2008 financial crisis were contemporaneous with the passage of dozens of anti-immigration laws—in 2010 and 2011 alone, US state legislatures passed 164 anti-immigration laws.63

World's Top Ten Host Countries for Refugees

WHO HOSTS REFUGEES? DISPELLING THE MYTHS

As of the end of 2015, there are a total of 65.3 million people forcibly displaced around the world. These are people displaced from their areas of origin or habitual residence. Among this staggering number are an estimated 21.3 million refugees, plus an additional 5.2 million Palestinian refugees. Worldwide there are 10 million stateless people who have been denied access to basic rights such as education, healthcare, employment, and freedom of movement.40

What may seem like a universal phenomenon, the burden of hosting forcibly displaced peoples is not shared equally in the world. The reality is that low and middle income countries host 86 percent of the world’s displaced people while high income countries host only 14 percent.41 The current refugee crisis is too often framed as primarily impacting countries in the European Union and North America, though the number of refugees hosted in countries neighboring the country of departure far exceeds the number of refugees and asylum-seekers hosted in the EU and US. The top 10 hosting countries welcomed more than 60 percent of all refugees and asylum seekers.42

The wealthiest nations in the world, with the exception of Sweden and Germany, host the fewest refugees relative to their population and wealth. Several European countries do host sizeable refugee populations, yet nine out of the top ten refugee hosting countries, per 1,000 inhabitants, are outside of Europe.43 The burden of forced migration has largely been placed upon nations that lack the capacity and resources to effectively integrate and absorb such a large influx of people.

Most Refugees per 1,000 Inhabitants

EASING THE FLOW OF CAPITAL, RESTRICTING THE MOVEMENT OF PEOPLE

Such anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment and heightened security measures speak to a key dynamic linking neoliberalization and securitization with regard to the present “refugee crisis” in particular and forced migration more broadly. Specifically, neoliberalization and securitization are two dynamics work hand in hand to ensure the free flow of capital alongside the limited flow of people.

First, renowned geographer David Harvey states, “the free mobility of capital between sectors, regions, and countries is regarded as crucial. All barriers to that free movement such as tariffs, punitive taxation, planning, and environmental controls are impediments that must be removed.”64

The direction of this free flow of capital between regions and countries is not even nor equitable. According to US-based Global Financial Integrity and the Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics, in 2012, the last year of recorded data, countries in the Global South received a total of $1.3 trillion, including all aid, investment, and income from abroad. Yet, that same year, roughly $3.3 trillion left these countries, meaning they sent a net of $2 trillion to Global North more than they received. Since 1980, these net outflows have totaled $16.3 trillion, contradicting the widely held belief that the Global South merely drains the resources of the Global North through aid of various sorts. According to the study, however, the greatest outflows have to do with unrecorded capital flight, with countries in the Global South having lost a total of $13.4 trillion unrecorded capital flight since 1980.65

Second, alongside the tearing down of barriers for the flow of capital, and the guarantee that such capital flows move uninterrupted from the Global South to the Global North, has been the continual creation of barriers to the movement of people. Such barriers have manifested in the “extreme vetting” of refugees and asylum seekers and the militarization of borders.

The goal of this seeming tension between the free flow of capital and the restricted movement of people and labor is to curb wealth redistribution—even if labor is able to move to areas with better pay and greater benefits, the state can still manage this movement by restricting or increasing immigration.69 Supported by anti-immigrant sentiment, state and private actors have been able to tightly regulate the flow of capital and people. As such, the present moment can be understood as one of both the free flow of capital from the Global South to the Global North, and the mass restriction of the flow of people from the Global South to the Global North.

ONE REFUGEE'S STORY

AHMAD WAS BORN AND RAISED in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Syria. Yarmouk, known as the "capital" of Palestinian refugee camps, was home to over 100,000 Palestinian refugees prior to 2011. Today only about 20,000 residents remain, as most of Yarmouk’s residents have fled violence, siege, and starvation that the Syrian civil war brought since 2011.

Ahmad’s grandparents were the first to come to Yarmouk. They fled their home in northern Palestine in 1948 when the state of Israel was established. During this time over 700,000 Palestinians were expelled from their native lands. They eventually settled in Yarmouk refugee camp, where they, and their children, and their children's children were born and lived until 2012.

In December of 2012, a MIG plane hit the Yarmouk camp with barrel bombs and at the same time the Free Syrian Army invaded the camp. Ahmad and his family fled to a relative's house in Damascus, taking shelter along with 25 other people in a three-bedroom house.

In 2011, after the Syrian war began, Ahmad was arrested by government security forces for writing messages of resistance on the walls of Yarmouk against the Syrian regime. He was tortured and interrogated for two weeks. When he was released, he was in a precarious position: he was not able to travel freely and he was also due for his mandatory conscription in the Syrian army.

At the time of his arrest he had been studying business management in the Damascus Training Center, and working in media at an online news site. Instead of going into hiding, he decided to leave his work and enlist in the army voluntarily, lest he be caught by the regime again. He stayed in the Palestine Liberation Army—the Palestinian faction of the Syrian military for four years—two and a half years longer than required because of the war.

In his fourth year of service, he injured his hand and needed surgery. He was able to leave his army servie. He knew this would be his only chance to escape wartorn Syria.

Ahmad knew that leaving Syria would be extremely dangerous and potentially fatal. He was now a target from all sides—from the Syrian regime for leaving the army and from the rebel groups for having served in the Syrian military. Even without these complications, the prospect of death was a constant given the continual bombing and violence all around him. Under threat of potential arrest and imprisonment.

After being in this position for three months, he met someone who advised him to fly from Damascus to Kamishli, a Kurdish-controlled area, advising that would be the best way to leave Syria. He paid $300 to this person to be able to pass through the airport in Damascus. Everything in Syria could be done with a bribe. After an hour-long flight, he arrived in Kamishli, and got in touch with another smuggler there. Because it is illegal for Palestinian Syrians to go to Kamishli, he had to pay $100 to pass through and another $50 to obtain a fake permit to be there

The first night in Kamishli, the smuggler was to take them across the Turkish border. Ahmad a group of about 15 others were told to get ready in the middle of the night to make the 7 kilometer walk to the border crossing, but were were stopped by Turkish border police before they got past the first kilometer. They were badly beaten and the border police threatened to kill them if they returned.

The second time they tried, they had to climb a wall about 3 meters high to cross into Turkey. As they were climbing, the police shot at them and they were forced to go back to the Syrian side of the border. The third time he tried, Ahmad got into Turkey. By this time he had spent $1,200 to get from Syria to Turkey in smuggler fees and bribes.

Once in Turkey, Ahmad went directly to Izmir, a city on the route to Germany where his sister and younger brother had already fled from Syria.

Ahmad arrived in Izmir in May 2016. The borders to European countires were already closed. He had no idea how severe the security and control at the borders were going to be. Having run out of money, and having heard stories about the incredible hardship faced by refugees in Greece, he decided to stay in Turkey and work on a cattle and goat farm. He did not have any documents proving that he was a refugee in Turkey, despite the fact that he had tried to get a Kimlik (proof of residency in Turkey). When he went to the Kimlik office, he gave them his identity card, and they returned it to him saying that Palestinians were not allowed to obtain a Kimlik.

Because he did not have papers, employers treated him poorly as they knew there would be no repercussions. On the farm, he worked 12 hour days and received about $225 per month, after paying for his board there.

He left for Istanbul to look for better work, although quickly learned how terrible the working conditions were for Syrians there. He was able to live in a small, three-bedroom apartment with nine other young Palestinian men. He worked in a furniture factory six days a week, getting paid a third of what his Turkish coworkers received for the same work, but without any benefits. He was continously filled with anxiety because he did not have employment papers—his main worry that if he were caught he would get deported back to Syria.

After three months, he saved up enough money to go back to Izmir because by September 2016 he had decided to try to go through Greece. He tried to leave Izmir 12 times over twenty days to get on a boat for Greece. He would wait for three hours in the forest in the middle of the night until the raft was ready. Once in the raft, the water would flood up to their waists in freezing cold water.

For the first elevent attempts the Turkish coast guard stopped them, make them get off the raft, which they would then destroy, and returning them to Turkey by coast guard ship. Four of the first eleven times they also beat the driver of the boat badly, who was also a refugee with no experience at sea. Once returned them to the port, they then had to go to the police station where they were photographed and fingerprinted. At the station, they would wait for 8-12 hours with about 30-60 people who were also attempting the journey to Greece. For these attempts, he paid the smugglers $600.

On the eighth attempt, they were in a jet boat. This boat only had capacity for 10 people but they crammed 20 people into the boat. The waves were massive and the boat was going to capsize so the driver made the younger people on the boat get out. The driver stopped on an island to drop them off and said he would come back to pick them up. The driver never came back. The six who got off the boat waited for two hours, but when they understood that he was not returning, they made a big fire to get anyone’s attention. The Turkish coast guard saw them but did nothing to help. It was the middle of the night, they were soaking wet in freezing cold rain, and they had no water, blankets, food, or any idea how to return to safety. When the sun came up, they decided to start walking to try and find help. They walked for hours and had to drink water from the sea. They tried to reach the smuggler and told him where they were but nobody came to help. One of the people had a number for a UN employee who then spoke with the Turkish police, after which the coast guard came back to rescue them. They had been out for 20 hours.

On the twelfth attempt, he was able to make it to Samos island in Greece. He was supposed to go to Chios but there no boats heading that direction.

Upon arriving in Samos, a police car came to get them and they were taken directly to the camp. They dropped them in front of the police office where they were forced to sleep outside on the rocky ground. It was raining. In the morning, they entered the police office where they were registered and fingerprinted. He was then assigned a tent and given clothes by an NGO.

Ahmad was shocked by the camp conditions in Samos. He did not imagine that the conditions could or would be so terrible. But the greatest shock was meeting people who said they had been there for seven months. He couldn't imagine staying in the camp for such a long time under such conditions.

WHEN WE MET HIM, Ahmad had been in Samos for four months. It had been a year since he left Syria. He says all he can think about is how he will not be able to reach Germany to be reunited with his brother and sister. With the borders more tightly controlled than ever, it is nearly impossible to get anywhere beyond the borders of Greece.

Ahmad's case is specially dire and challenging because Palestinians coming from Syria were not being registered for the asylum process. Today many appeals by Syrians for admissibility to Greece are getting denied. They are often imprisoned and await deportation to Turkey.

Currently trapped in Greece and with very little hope, Ahmad still expresses his belief that his story is not so bad especially after witnessing what so many others have endured and do still endure—many refugee children have been denied education for years, elders and the disabled have been forced on perilous journeys with no basic necessities and no help, and women have been taken advantage of and abused, along with the many others who have died along the way.

At this point, all he wants is to be settled somewhere— anywhere—after all the conditions he has endured. Before, he would never have imagined staying in Greece, but now he simply wants to get asylum anywhere.

SECURITIZATION IN THE ERA OF TRUMP

Since entering office, and under the banner of putting the United States “first,” President Trump has put force behind his central campaign pledge to toughen immigration enforcement. For example, he has signed executive orders to start construction of a border wall, expand authority to deport thousands, increase the number of detention cells and hiring of more than 10,000 of Immigration and Customs Enforcements (ICE) employees, and vow to punish cities and states that refuse to cooperate (i.e., “sanctuary cities”). Further, as of June 2017, a watered down version of President Trump’s “immigration ban” went into effect, prohibits for 90 days the entry of travelers from six predominantly Muslim countries—Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen—unless they have a “bona fide relationship" with a person, business or university in the US.70

Taken together, his efforts have highlighted the centrality of securitization to the management of flows of peoples and capital (including labor itself). Yet they have also highlighted the centrality of racial and colonial difference itself to such dual dynamics, as they have targeted immigrants from Latin America and from majority-Muslim countries in the Middle East and Africa.

Such measures have of course been met with fierce opposition from countless labor groups, academic organizations, state and local governments and courts, community organizations, and others. For example, in legal challenges to Trump’s “immigration ban,” plaintiffs have cited legal precedents that state that the government cannot act arbitrarily or without supportive evidence. Further, many cities have made efforts to shield undocumented immigrants from immigration officials. In late March 2017, for example, Los Angeles passed a directive forbidding firefighters and airport police from cooperating with federal immigration agents. On the other hand, several states have been attempting to leverage economic power to force more liberal cities to cooperate with immigration officials, with lawmakers in Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Wisconsin and Texas introduced bills to penalize sanctuary cities.

COLONIAL AND IMPERIAL ROOTS OF SECURITIZATION

Just as neoliberalism’s austerity and debt regimes have their roots in colonial and racialized expropriations of many kinds, neoliberalism’s security regime draws from long histories of colonial counter-insurgency.71 We can understand those security methods deployed alongside, and in service of, neoliberal austerity and debt regimes as elaborations and extensions of the histories of violence constitutive of European and US power and wealth.72 Most recently, such security regimes extend the key strategies of US war-making in the Global South during much of the twentieth century, and the militarized management of displaced peoples in particular.

The explicitly militarized forms of colonial and imperial appropriation from which neoliberalism’s security regime have taken shape have manifested differently depending on the geographic and historical context. For example, as the next section addresses in further detail, for the Asia-Pacific region, it was after World War II that colonialism and militarism converged. US military leaders turned the region’s islands into a Pacific “base network” that would support US military deployment in allied Asian countries as part of the containment of communism.73 Significantly, this network would also be essential in the management of refugees from the region fleeing both political persecution and aggressions by the US government and corporations. Histories such as these laid the groundwork for contemporary strategies for managing unwanted populations, including the militarization of borders, proliferation of surveillance technologies, and the legal formations that undergird dispossession, expropriation, and displacement.