This report is a Joint Stakeholder submission to the United Nations Human Rights Council on behalf of the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley and the Council on American-Islamic Relations for the 4th Universal Periodic Review cycle of the United States government. The report was submitted on April 7th 2025 to the United Nations Committee on the 4th Universal Periodic Review (UPR).

This publication is part of the Global Justice Program’s Human Rights Agenda report series. In this series, we collaborate with other human rights, civil rights, and civil society organizations to advance the utility of the rights-based framework as a meaningful organizing tool for impacted communities and social movements to articulate claims of social, cultural, and political rights, and belonging. Our reports are reviewed by the United Nations Human Rights Commission and the Human Rights Council, and inform the UN’s recommendations to hold the US Government and legislative bodies accountable to their obligations as related to the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), the International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Click here to read this report in PDF format.

I. Summary of the Issue: The Consequences of Islamophobia on Civil Liberties and Rights in the United States and its Implications for Muslim Americans

- This joint stakeholder report, submitted on behalf of the Othering & Belonging Institute (OBI) and the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), serves as a written contribution to the 4th Universal Periodic Review cycle to support the UN Human Rights Council’s review of the United States’ human rights obligations and commitments.

- While this submission will focus on the evidence of continuous and increasing violations of Muslim American civil liberties and rights by the US government, the measurable impacts of Islamophobia as affecting the daily lives of Muslim Americans, and the prevalence of institutionalized Islamophobia in state and federal government policies, it must be noted that Islamophobia is a global phenomenon, impacting Muslims around the world.[1] Islamophobia is a form of legal, political, and social othering of, and discrimination against, Muslims and people perceived to be Muslim. In the US, Islamophobia at the interpersonal level is expressed through prejudicial views, discriminatory language, and acts of verbal and physical violence toward Muslims and those perceived to be Muslim. At the structural and institutional levels, Islamophobia manifests through the policing, profiling, surveillance, torture, and detention of people along racial/ethnic and religious lines, US state laws, federal policies, US national security policy, and the militarization of foreign policy. Furthermore, in the United States, Islamophobia is built on the existing foundations of xenophobia, structural racism, and racialization, and has existed well before September 11, 2001. The US federal and state governments and elected government officials are largely responsible for exacerbating and institutionalizing Islamophobia in the United States and have done far too little to address its impacts, or to prevent Islamophobia from spreading in the first place.

A. Islamophobia in the Current Political Climate

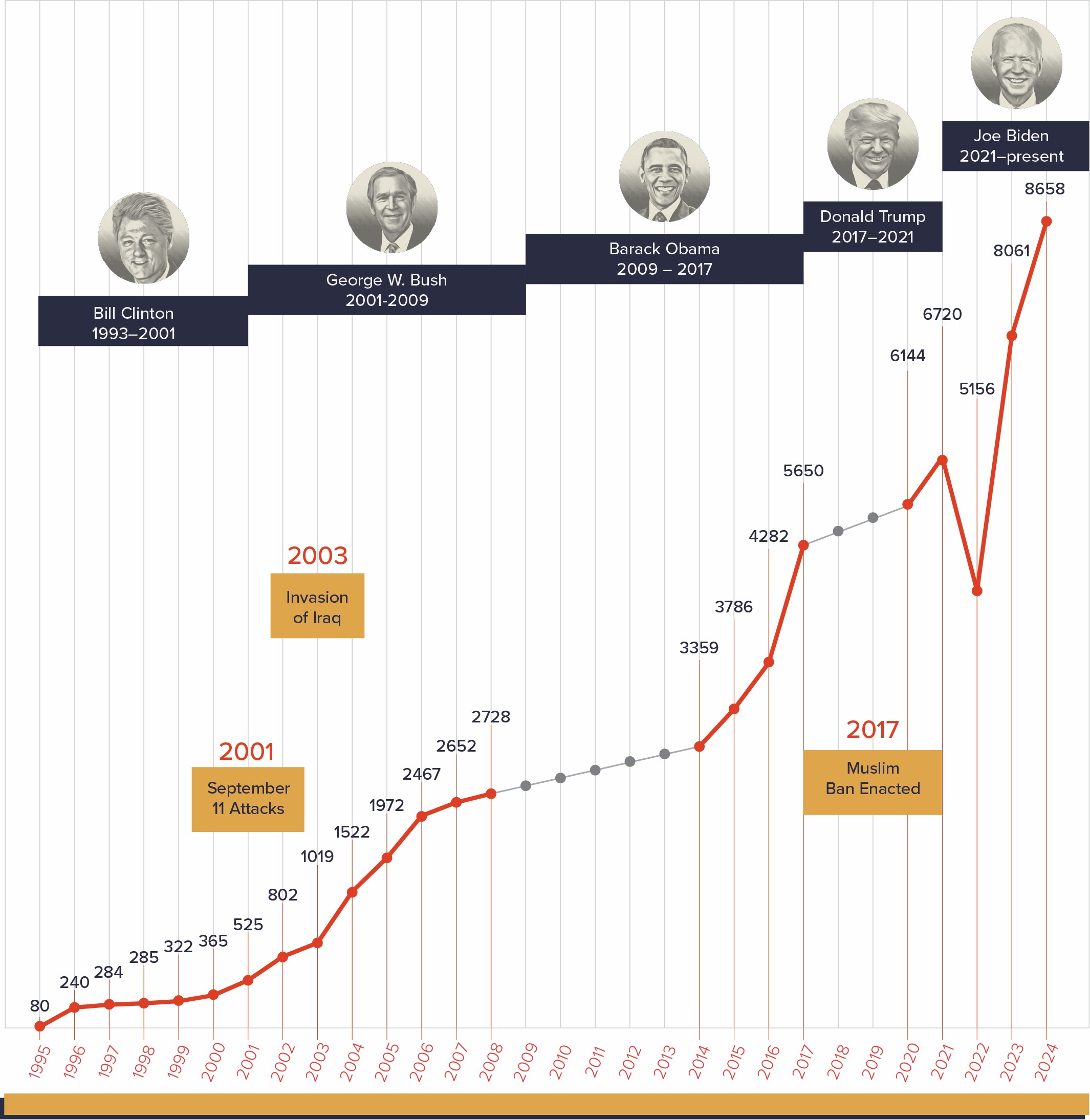

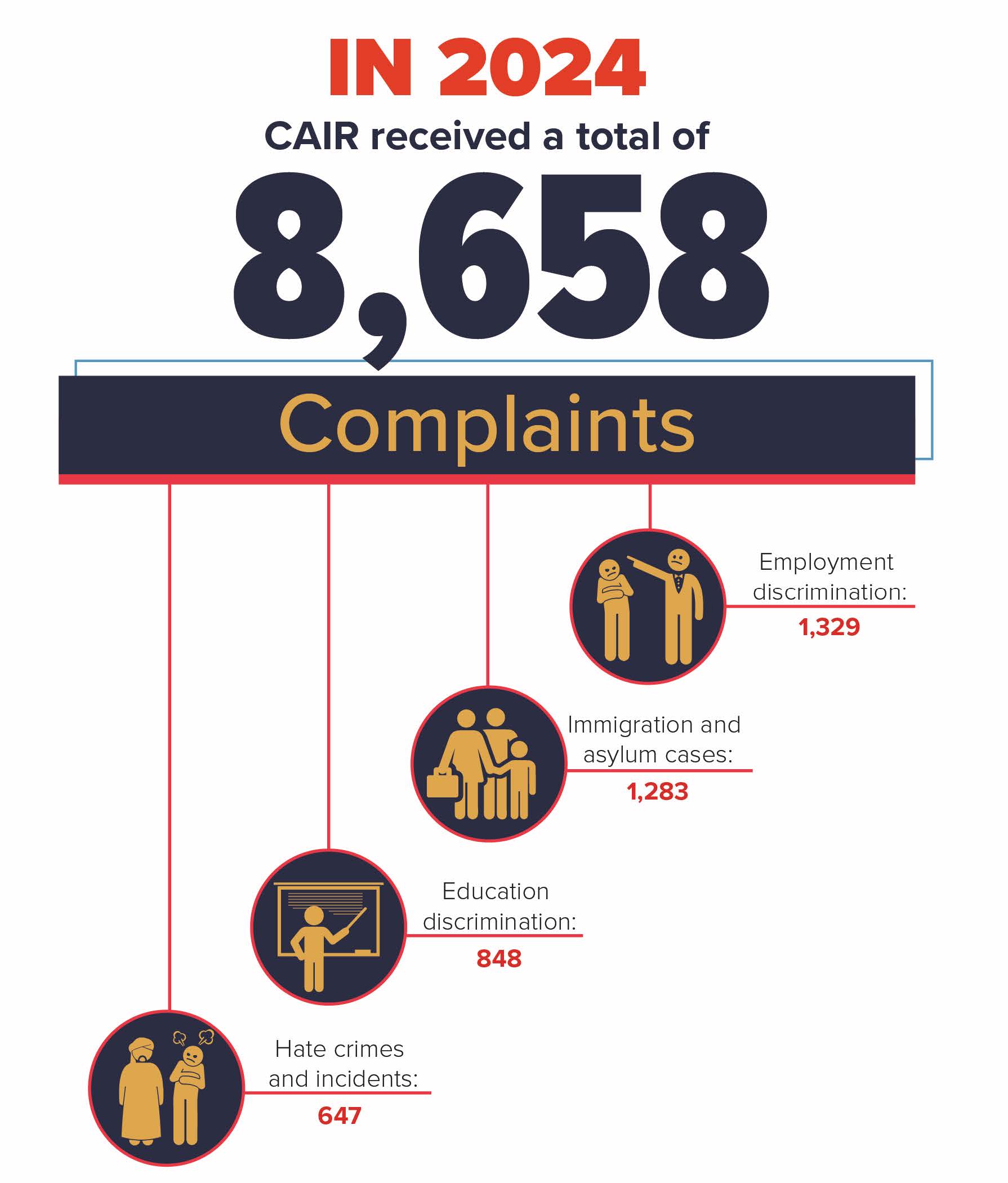

- To provide some context to the current political climate in the United States, for nearly 18 months, the United States government has threatened the civil liberties and rights of Muslim Americans by promoting Islamophobic rhetoric to justify the suppression of American individuals and civil society groups calling attention to the state of Palestinian human rights. In 2024, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) received 8,658 complaints from individuals across the United States, the highest number of complaints ever reported to the organization in its 30-year history, suggesting that Islamophobia has reached a record high across the country.

- In a January 30, 2025 Executive Order, the United States government referred widely to student-led protests for Palestinian rights as “pro-jihadist protests.”[2] In February 2025, Elon Musk, who leads President Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency, falsely labeled numerous Muslim American and Arab American groups as “terrorist organizations” in a post on X.[3] False attempts to conflate nonviolent activism in support of Palestinian rights with notions of violence rely on long-standing tropes that Muslims and Arabs are innately violent, which facilitates Islamophobic and anti-Palestinian sentiment in the United States. On March 8, 2025, explicit attacks on Muslim Americans and Palestinians escalated when, under orders of the Trump administration, Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia University student and legal US resident, was detained by Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) following reports of his participation in peaceful campus protests for Palestinian rights. His detainment appears to rely solely on Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s determination that Khalil’s presence in the United States could have “potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences.”[4]

B. Measuring the Impact and Consequences of Islamophobia on Muslim Americans

- For nearly 18 months, the United States government has, therefore, through its actions, promoted and facilitated nationwide Islamophobic and anti-Palestinian sentiment. The impact of this rhetoric on Muslim American civil liberties is reflected in the data reported to the Council on American-Islamic Relations, which is collected by intake staff and attorneys at 22 offices across the United States. In 2024, CAIR offices received 8,658 incoming complaints nationwide, an all-time high for the organization. May 2024 witnessed the highest number of complaints reported in one month, likely due to increased attacks on peaceful student protesters by government and university officials. The number of complaints received in 2024 is also a 7.4% increase over the 8,061 complaints reported in 2023, which was the highest number ever reported to CAIR. Nearly half, or 44%, of all complaints reported in 2023 were received between October and December 2023, indicating a correlation between the attacks on Palestinian civilians in Gaza and a rise in Islamophobic sentiment in the United States.

- The United States government’s failure to protect Muslim American civil liberties has permeated most clearly in the employment and education sectors, where Muslim, Arab, and Palestinian employees and students report being targets based on their faith, race, ethnicity, and viewpoints. In 2024, employment discrimination was the highest reported category to CAIR at 1,329 complaints, or 15.3% of all reported complaints. This is also a 136% increase over the number of employment discrimination complaints reported in 2022, prior to the war in Gaza and widespread nationwide promotion of Islamophobic and anti-Palestinian rhetoric by government officials. Reports from employees across industries indicate that employers, particularly ones who have expressed commitments to inclusive work cultures, have refused to tolerate identity-related speech from Muslim and Arab employees. Muslim and Arab employees, particularly those who choose to share Palestine-related speech at and outside of the workplace, have therefore been primary targets of disciplinary measures, even as they report that other employees have been free to share or engage in non-Palestine-related identity and political speech with no similar consequences.

- Education-related complaints have also steadily increased. In 2024, 1,143 education-related complaints were reported, including incidents of bullying and education discrimination at the K-12 level and the level of higher education. This also marks a 296% increase over the number of education-related complaints reported in 2022. Throughout 2024, reports emerged that university and college administrators across the United States had failed to protect Muslim, Palestinian, and Arab students from incidents of harassment and discrimination. Moreover, many universities sought to explicitly stifle protests in support of Palestinian human rights, introducing new campus-wide policies with the seeming intent of suppressing free speech following the establishment of Palestine-related demonstrations, calling on local and state law enforcement to disperse peaceful protesters, and deploying institutional disciplinary procedures to suspend, expel, and revoke degrees of student protesters. The Biden administration failed to condemn the use of state violence against peaceful protesters, and the Trump administration appears to now be targeting individuals who have engaged in protest for detainment and deportation. Targeting of foreign students comes amid pressure from state officials for universities to punish student protesters, such as recent demands from the House Committee on Education and the Workforce for Columbia University and Barnard College to disclose student disciplinary records under threat of losing federal funding. In doing so, US government officials appear to be attempting to coerce universities to suppress free speech that the government disfavors.[5]

- Complaints involving encounters with state and local law enforcement have also rapidly increased amid escalating Islamophobic sentiment across the United States. In 2024, CAIR received 506 complaints involving encounters with law enforcement, a 71.5% increase over the previous year. Thirty percent of all complaints involving law enforcement encounters were reported just in May 2024. This increase reflects the widespread deployment of law enforcement to disperse peaceful student protesters following the establishment of student-led sit-ins, or “encampments,” at over 100 colleges and universities across the country. An external analysis of encampment-related demonstrations between October 2023 and May 2024 found that 95% of such demonstrations involved “no reports of encampment protesters engaging in physical violence or destructive activity.”[6] Still, law enforcement had “been involved in over one-fifth of all encampment demonstrations” and had arrested or detained over 3,000 people on campuses as of May 2024.[7]

- Finally, the United States government’s facilitation of widespread Islamophobic sentiment has also threatened the safety of Muslims conducting everyday business in public spaces, as well as Islamic religious and cultural institutions broadly. In 2024, CAIR received 647 complaints of hate crimes and incidents, a 453% increase over the number of complaints received in 2022. Hate crimes and incidents include reports of verbal harassment and physical assault targeting Muslims and vandalism and destruction targeting Islamic institutions. Public examples of such hate crimes include the murder of 6-year-old boy Wadea Al-Fayoume in October 2023[8] and the attempted drowning of a 3-year-old Muslim girl in May 2024.[9]

- In addition to normalizing an atmosphere of Islamophobic and anti-Palestinian sentiment that has restricted the civil liberties of Muslim Americans, the United States government has also directed law enforcement agencies to target Muslims. In 2024, reports to CAIR indicated that the government was using the Threat Screening Center, formerly known as the Terrorism Screening Database and colloquially referred to as the federal watchlist, to target Palestinian and Muslim activists. The federal government appears to be using the watchlist, which has long been suspected of disproportionately targeting Muslim individuals, to suppress Palestinian and Muslim activists’ lawful exercise of their constitutional rights to promote Palestinian rights.[10]

- To better understand and measure the impact of Islamophobia on Muslim Americans, the Othering & Belonging Institute (OBI) developed and administered the first-ever national survey to assess Islamophobia’s prevalence from the perspectives of Muslims. What’s more, the study, Islamophobia Through the Eyes of Muslims: Assessing Perceptions, Experiences, and Impacts, sought to account for the diversity of US Muslims and to assess their societal engagement, worldviews, and belonging as they navigate their lives in the US.[11] OBI’s study, which was conducted in 2020, was groundbreaking as it uplifted and centered the collective experiences and voices of Muslim Americans so the public could hear directly from the affected community. In 2021, OBI’s study and a report by CAIR Remembrance and Resilience: American Muslims Twenty Years After 9/11[12] were referenced by US Representatives (D-MN) Ilhan Omar and (D-IL) Jan Schakowsky as background research and evidence in support of H.R. 5665 - Combating International Islamophobia Act.[13] A total of 1,123 Muslim Americans participated in the survey, and their responses narrate and inform the key findings below[14] which both illuminate a measurable othering of Muslims and the grave repercussions of Islamophobia on Muslim Americans.

- In the assessment of Muslims’ Perceptions of Islamophobia in the US OBI researchers sought to understand Muslim Americans’ beliefs about Islamophobia.[15] The findings indicated that irrespective of age, gender, or if the survey participants were US- or foreign-born, nearly all participants believe that Islamophobia exists in the US (97.8%). In addition, almost all survey participants (95%) agree that Islamophobia is a problem in the US. Close to two-thirds of respondents (60.6%) assess Islamophobia to be a very big problem. Notably, over a third (34.3%) of all participants first noticed the existence of Islamophobia prior to 2001, suggesting that more Muslims who participated in the survey were already aware of Islamophobia prior to September 11, 2001. In assessing those most impacted by Islamophobia, almost three-quarters of participants (74.3%) believe that women are more at risk of experiencing Islamophobia. Significantly, over half of participants (55.4%) have personally encountered an incident but did not report it to the authorities, and 32.1% have never personally encountered it. Only 12.5% of participants have reported an incident to the authorities. What’s more, almost two-thirds of respondents (65.7%) that encountered an Islamophobic incident did not know where to report the incident.

- The assessment of US Muslims’ Experiences with Islamophobia sheds light on the othering of Muslims and the lived experiences of the survey participants in relation to Islamophobia.[16] A staggering two-thirds of participants (67.5%) have personally experienced Islamophobia in their lifetimes. Survey respondents aged 18–29 were more likely to have personally experienced Islamophobia than any other age group (81.2%), and in general, younger respondents were more likely than older respondents to have personally experienced Islamophobia. What’s more, women are more likely than men to have had a personal encounter with Islamophobia (women: 76.7%, men: 58.6%). Regardless of age, gender, or place of birth, almost two-thirds of participants (62.7%) responded that they themselves, or family members, friends, or members of their community, have been affected by federal and/or state policies that disproportionately discriminate against Muslims. Notably, more than half (53.3%) of respondents have been treated unfairly by a law enforcement officer because of their religious identity.

- The study also assessed the Social, Psychological, and Emotional Impacts of Islamophobia on US Muslims.[17] When assessing the psychological and emotional impacts of Islamophobia on US Muslims, most survey participants (93.7%) responded that Islamophobia affects their emotional and mental well-being. In assessing the social impacts of Islamophobia on US Muslims, almost one-third of survey participants (32.9%) at some point in their lives hid or tried to hide their religious identity, while over two-thirds (67.1%) have never done so. In addition, regardless of age, most respondents (88.2%) censor their speech or actions out of fear of how people might respond or react to them. Significantly, women censor themselves at a higher rate (91.8%) than men (84.6%).

- The assessment of the Societal Engagement of US Muslims provides an analysis of survey participants’ efforts toward community building, intercultural mixing, and civic engagement, and how Islamophobia impacts those efforts.[18] Regardless of age, gender, or place of birth, almost all respondents (99.6%) socialize with non-Muslim groups, and more than half (51.5%) very often socialize with non-Muslim groups. Yet, 79.2% of participants said that Islamophobia prevented them from building social connections with non-Muslims. In contrast, 69.9% of respondents find it difficult to build community with other US Muslims because of Islamophobia. In assessing US Muslims’ civic engagement, 76.5% of participants feel uncomfortable making demands on their local authorities or congressperson.

- Lastly, the assessment of US Muslims’ Worldviews and Belonging measures survey participants’ social and religious worldviews, their perspectives on race and relations between Muslims and non-Muslims, and their sense of belonging.[19] Notably, most survey participants (79.4%) agree that Islamic values are consistent with US values, and 40% of participants strongly agree. In considering diversity, irrespective of age, gender, or place of birth, nearly all participants (99.1%) agree — with 91.9% strongly agreeing — that it is a good thing that the US society is made up of people from different cultures. Most participants (97.1%) also agree that racial prejudice is a major problem in the US. What’s more, almost all respondents (99%) agree that all races and ethnicities should be treated equally. On the role of the US media’s portrayal of Muslims, almost all respondents (97.5%) agree that the US mainstream media’s portrayal of Muslims is unfair. In addition, most respondents (93.7%) agree that it is important to them that their children are, or would be, fully accepted as Americans.

C. Institutionalized Islamophobia in US State Legislation and Federal Policies

- For over two decades and spanning five US presidencies, Islamophobia has been institutionalized by both Republican and Democratic administrations, and the US federal government and state governments have infringed on the freedoms of its citizens and lawful residents by systematically enacting federal measures and state legislation that disproportionately discriminate against, and other Muslims. Since 2001, at least 23 federal measures were either introduced or enacted that target and discriminate against Muslim Americans as well as Muslims globally, the most recent of which was President Trump’s Travel Ban which was rescinded in 2021 by former President Biden.[20] These measures subject Muslims to unwarranted surveillance, detention, profiling, exclusion, travel restrictions, and discrimination along the lines of race, ethnicity, national origin, and religion.

- Furthermore, one of the most evident markers of institutionalized Islamophobia is the rise of anti-Sharia legislation in US state legislatures, demonstrating that discriminatory, anti-Muslim sentiment and policy are not limited to the US federal government. Since 2010, 223 anti-Sharia bills have been introduced in 44 state legislatures across the US.[21] Among those introduced, 20 bills have been enacted in 13 states. These bills impose legal barriers that specifically seek to prevent Muslims from engaging fully and freely with their religion by preventing Islamic interpretations that guide ethical and moral life, as outlined in Sharia,[22] from being considered in US state courts and by infringing on the rights of Muslims to enter into contracts based on Sharia.[23] In addition to stoking an unwarranted fear of Islam and Muslims, the most direct legal implication of anti-Sharia legislation is that it bars courts from enforcing individual contracts that call for the application of foreign law, including Sharia. Thus, it infringes on an individual’s right to freedom of contract and prevents wills, marriage contracts, business contracts, etc., that are written according to Sharia from being recognized or enforced. Anti-Sharia legislation, therefore, strips Muslims of their legal rights as afforded by the First Amendment of the US Constitution, infringes on the Establishment Clause, as well as undermines the US Constitution, and sabotages judges’ ability to reasonably consider foreign law in their rulings. The harmful intent of these bills is to single out Muslims by way of barring the application of Sharia in US courts and to proliferate a culture of fear and intolerance towards Muslim Americans. Crucially, anti-Muslim bills are sweeping, and the underlying reality is that anti-Muslim legislation threatens the civil and constitutional rights of not only Muslims but all individuals. The unintended consequences of these laws also undermine the ability of courts to interpret laws and treaties regarding global business and international human rights.[24]

- These federal measures and state legislation are preventing the US from maintaining its obligations and commitments to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), as well as US-ratified international treaties, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

Figure 3. Timeline of Anti-Muslim Federal Measures from 2001 - 2025

Click here to see our full Islamophobia Legislative Database

II. Assessment of and Comments on the Implementation of Recommendations and Developments since the 3rd UPR Cycle

- Regarding recommendations put forth during the 3rd UPR Cycle to the United States government, this report identifies the following recommendations that specifically address the issue of Islamophobia and the infringement of Muslim American civil liberties and rights. We have provided our assessment of the implementation of these recommendations below:

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government does not support Recommendation 26.128 proposed by Pakistan to take significant steps to end Islamophobia as well as hate speech, including by means of criminalization[25] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.8).[26]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports Recommendation 26.134 proposed by Algeria to address Islamophobia and racial profiling on a non-discriminatory basis that would be applicable to all religious groups[27] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.6).[28]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports Recommendation 26.135 proposed by Malaysia to bolster efforts to combat racial profiling, discrimination, incidents of Islamophobia, and religious intolerance, including if these incidents are carried out by the authorities[29] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.6).[30]

- Other recommendations provided during the 3rd UPR Cycle that directly address issues of religious intolerance, law enforcement, xenophobia, and the enforcement of international human rights treaties and that correlate with the consequences of Islamophobia and its impacts on Muslim Americans’ civil liberties and rights include the following:

- On the theme of Treaties, International Mechanisms, and Domestic Implementation, the US government does not support Recommendation 26.100 proposed by Albania to establish a federal mechanism to coordinate compliance in regards to international human rights instruments at the local, state, and federal levels[31] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.22).[32]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.112 proposed by Slovakia to take steps to review policies at the federal, state, and local level to better prevent xenophobia, racism, racial discrimination, and related intolerance[33] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[34]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.113 proposed by Russia to take measures to eradicate discrimination based on race, religion, ethnicity, and sex, as well as to prevent racial profiling by law enforcement[35] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[36]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.126 proposed by South Africa to adopt and promote at the national level a plan to address racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance[37] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[38]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.127 proposed by Qatar to adopt measures to advance equality and eradicate xenophobia and racial discrimination against migrants, refugees, racial, ethnic, and religious minorities[39] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[40]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.129 proposed by Bahrain to protect minorities and vulnerable groups in the US from hate speech and intolerance[41] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[42]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.133 proposed by Mexico to eliminate xenophobic speech, discrimination, and excessive use of force and racial profiling[43] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[44]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports Recommendation 26.139 proposed by Ghana to ensure that domestic and international laws to end all forms of discrimination related to race, sex, and religion are implemented in full and that perpetrators are brought to justice[45] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.6).[46]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports Recommendation 26.258 proposed by Saudi Arabia to combat religious discrimination when conducting investigations, inspections, and other interrogations in regards to law enforcement[47] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.6).[48]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports Recommendation 26.260 proposed by Turkey to counter institutionalized racism, particularly within law enforcement agencies, and to improve the legal framework to hone in on eradicating discrimination and intolerance toward racial, ethnic, and religious groups[49] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.6).[50]

- On the theme of Civil Rights and Non-Discrimination, the US government supports in part Recommendation 26.266 proposed by China to address religious intolerance and xenophobic violence[51] (Source of Position: A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 - Para.7).[52]

- There have been some noteworthy efforts made by the US government to address Islamophobia at the national level, notably, former President Joe Biden's rescission of the Travel Ban, otherwise known as the Muslim Ban, on the day of his inauguration on January 20, 2021. Additionally, in 2023 the US Department of State observed the first International Day to Combat Islamophobia,[53] and in December 2024 the White House released a national strategy to counter Islamophobia and Anti-Arab hate which was intended to counter Islamophobia as well as to ensure that Muslim and Arab Americans enjoy and have access to the same liberties and opportunities as their fellow Americans.[54] However, the strategy was criticized by civil rights organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union for not concretely addressing the bias-infused government laws and programs that disproportionately impact Muslims and those perceived to be Muslim, underscoring how the Biden administration and the national strategy failed to recognize how anti-Muslim discrimination for decades has been institutionalized and embedded in US government policies.[55] There was also a concerted effort in 2021 led by US Congress members Ilhan Omar (D-MN) and Jan Schakowsky (D-Illinois) to enact legislation H.R. 5665 - Combating International Islamophobia Act. On February 28, 2025 US Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ), and US Representatives Ilhan Omar and Jan Schakowsky reintroduced the Combating International Islamophobia Act to address the global uptick in Islamophobic incidents.[56] The Act, if passed, would require the State Department to establish a Special Envoy for Monitoring and Combating Islamophobia and would position the United States as leaders in confronting anti-Muslim bigotry on a global level.[57]

- In conclusion, the firsthand evidence and analysis provided in this report highlights how, since the last UPR review in 2020 and long before then, the United States government has been negligible on the issue of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim discrimination, demonstrating how Islamophobia has in fact increased over the years in the US by way of the US government unlawfully violating Muslim Americans’ civil and constitutional rights, and how Islamophobia greatly infringes on the everyday lives of Muslim Americans, as well as the far-reaching consequences of institutionalized anti-Muslim discrimination by way of state laws and federal policies. Since the 3rd Cycle of the UPR, the US government has failed to fully implement the recommendations it claims to support.

III. Recommendations:

- In order to uphold its constitutional and international commitments to safeguard human rights, the US government must extend and protect human rights of all persons within its jurisdiction, regardless of race, religion, or national origin. To achieve this, the US government must:

- Cease in the detainment and deportation of law-abiding foreign students engaging in constitutionally protected free speech.

- Suspend the FBI’s dissemination of the federal watchlist, which previously leaked documents indicate is almost wholly comprised of Muslim names and which appears to be wielded by the federal government to target individuals engaging in Palestine-related activism.

- Protect the rights of Muslim individuals as enshrined in the US Constitution and rule of law, and recognize Islamophobia as a form of religious discrimination and hatred based on national origin or other manifestations of hatred against ethno-religious groups.

- Prevent the enactment of discriminatory anti-Muslim policies by establishing a single mechanism to coordinate compliance that would apply at state and local levels.

- Prevent the unlawful infringement of Muslim American civil liberties and rights and the enactment of discriminatory anti-Muslim policies by ensuring that the US Constitution, ICERD, and ICCPR are fully implemented at federal, state, and local levels.

- Ensure the federal government addresses the issue of the enactment of anti-Sharia legislation by working with state governments to immediately rescind the 20 anti-Sharia bills that have been passed into law, as well as to implement policies to prevent anti-Sharia legislation from being introduced and enacted.

[1] Ahmed Shaheed, Countering Islamophobia/anti-Muslim hatred to eliminate discrimination and intolerance based on religion or belief: Report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, (United Nations, 2021), https://www.ohchr.org/en/calls-for-input/report-countering-islamophobiaanti-muslim-hatred-eliminate-discrimination-and.

[2] “Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Takes Forceful and Unprecedented Steps to Combat Anti-Semitism,” The White House, January 30, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/01/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-takes-forceful-and-unprecedented-steps-to-combat-anti-semitism/.

[3] Elon Musk (@elonmusk), “As many people have said, why pay terrorist organizations and certain countries to hate us when they’re perfectly willing to do it for free?” X, February 23, 2025, https://x.com/elonmusk/status/1893669748405080313.

[4] Cate Brown, Maria Sacchetti, and Shayna Jacobs, “Effort to Deport Columbia Student Rests Solely on Rubio Decision,” The Washington Post, March 12, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/2025/03/12/marco-rubio-mahmoud-khalil-deportation/.

[5] “Breaking: CAIR-NY, CAIR, Dratel and Lewis Announce Lawsuit on Behalf of Mahmoud Khalil, Others Against House Committee and Columbia U for Compelled Disclosure of Private Student Records,” CAIR, March 13, 2025, https://www.cair.com/press_releases/breaking-cair-ny-cair-dratel-and-lewis-announce-lawsuit-on-behalf-of-mahmoud-khalil-others-against-house-committee-and-columbia-u-for-compelled-disclosure-of-private-student-records/.

[6] Bridging Divides Initiative, “Issue Brief: Analysis of U.S. Campus Encampments Related to the Israel-Palestine Conflict,” Princeton University, May 21, 2024, https://bridgingdivides.princeton.edu/updates/2024/issue-brief-analysis-us-campus-encampments-related-israel-palestine-conflict.

[7] Bridging Divides Initiative, “Issue Brief.”

[8] Nadine Yousif, “Illinois Man Convicted for Hate Crime Murder of Palestinian Boy,” BBC News, February 28, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cyveq30lmdlo.

[9] “CAIR-TX Welcomes Indictment in Attempted Drowning of Palestinian-American Muslim Child,” CAIR, September 3, 2024, https://www.cair.com/press_releases/cair-tx-welcomes-indictment-in-attempted-drowning-of-palestinian-american-muslim-child/.

[10] “CAIR, CAIR-LA Announce Suit Against FBI for Using Illegal, Racist Watchlist Against Palestinian Americans,” CAIR, August 12, 2024, https://www.cair.com/press_releases/cair-cair-la-announce-suit-against-fbi-for-using-illegal-racist-watchlist-against-palestinian-americans/.

[11] Elsadig Elsheikh and Basima Sisemore, Islamophobia Through the Eyes of Muslims: Assessing Perceptions, Experiences, and Impacts (Berkeley, CA: Othering & Belonging Institute, 2021), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/islamophobia-survey.

[12] Remembrance and Resilience: American Muslims Twenty Years After 9/11 (Washington, DC: Council on American-Islamic Relations, 2021), https://www.cair.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/911_survey_report_1.pdf.

[13] “House Foreign Affairs Committee Passes Combating International Islamophobia Act,” omar.house.gov, December 10, 2021, https://omar.house.gov/media/press-releases/house-foreign-affairs-committee-passes-combating-international-islamophobia.

[14] Elsadig Elsheikh and Basima Sisemore, Islamophobia Through the Eyes of Muslims, 4 - 7.

[15] Ibid, 5.

[16] Ibid, 5 - 6.

[17] Ibid, 6.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid, 6 - 7.

[20] “Islamophobia Legislative Database,” Othering & Belonging Institute, March 2025, https://belonging.berkeley.edu/islamophobia/islamophobia-legislative-database.

[21] Ibid.

[22] To challenge the Islamophobic rhetoric and disinformation associated with Sharia, it’s important to note what Sharia actually is. Islamic law experts define Sharia as a moral code or guiding principles founded on the teachings of the Quran and the Hadith (the teachings and actions of the prophet Mohammed). The interpretation of Sharia is called “fiqh,” meaning Islamic jurisprudence, however, Sharia is not the equivalent of Islamic law or an Islamic legal system. It is an evolving methodology for devout Muslims to discern God’s guidance to lead an ethical and moral life. Sharia therefore guides Muslims on how to live and engage with the world, ranging from what they can or cannot eat, to how they conduct business and personal affairs, and more.

[23] Elsadig Elsheikh, Basima Sisemore, and Natalia Ramirez Lee, Legalizing Othering: The United States of Islamophobia (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2017), https://belonging.berkeley.edu/legalizing-othering.

[24] “Oppose – HB 419: The Anti-Sharia Law Bill,” The American Civil Liberties Union – Idaho, Jan. 31, 2018, https://www.acluidaho.org/en/publications/oppose-hb-419-anti-sharia-law-bill.

[25] Human Rights Council, “A/HRC/46/15 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America,” United Nations General Assembly, December 15, 2020, pg. 13, https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/us-index.

[26] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” March 4, 2021, p. 3. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr/us-index.

[27] Human Rights Council, pg. 13.

[28] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[29]Human Rights Council, pg. 13.

[30] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[31] Human Rights Council, pg. 11.

[32] A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 7.

[33] Human Rights Council, pg. 12.

[34] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 3.

[35] Human Rights Council, pg. 12.

[36] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 3.

[37] Human Rights Council, pg. 12.

[38] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 3.

[39] Human Rights Council, pg. 13.

[40] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[41] Human Rights Council, pg. 13.

[42] A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[43] Human Rights Council, pg. 13.

[44] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[45] Human Rights Council, pg. 13.

[46] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[47] Human Rights Council, pg. 19.

[48] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[49] Human Rights Council, pg. 20.

[50] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 2.

[51] Human Rights Council, pg. 20.

[52] “A/HRC/46/15/Add.1 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review* United States of America, Addendum Views on conclusions and/or recommendations, voluntary commitments and replies presented by the State under review,” pg. 3.

[53] Antony J. Blinken, “Observing the First International Day to Combat Islamophobia,” U.S. Department of State, March 15, 2023, https://2021-2025.state.gov/observing-the-first-international-day-to-combat-islamophobia/.

[54] “Biden-Harris Administration Releases First-Ever U.S. National Strategy to Counter Islamophobia and Anti-Arab Hate,” The White House, December 12, 2024, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/12/12/biden-harris-administration-releases-first-ever-u-s-national-strategy-to-counter-islamophobia-and-anti-arab-hate/.

[55] Hina Shamsi, “ACLU Statement on New White House Strategy to Counter Islamophobia,” American Civil Liberties Union, December 13, 2024, https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/statement-on-new-white-house-strategy-to-counter-islamophobia.

[56] “Booker, Omar, Schakowsky Reintroduce Bill to Address Rising Islamophobia Worldwide,” Cory Booker, February 28, 2025, https://www.booker.senate.gov/news/press/booker-omar-schakowsky-reintroduce-bill-to-address-rising-islamophobia-worldwide.

[57] Ibid.