Click to download a PDF of this report.

This report is published by the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. The Institute engages in innovative research and strategic narrative work that attempts to reframe the public discourse from a dominant narrative of control and fear towards one that recognizes the humanity of all people, cares for the earth, and celebrates our inherent interconnectedness.

The report was submitted on April 26, 2019 to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

This publication is part of the Global Justice Program’s Human Rights Agenda report series. In this series, we collaborate with other human rights, civil rights, and civil society organizations under the umbrella of the US Human Rights Network (USHRN) to advance the utility of the rights-based framework as a meaningful organizing tool for impacted communities and social movements to articulate claims of social, cultural, and political rights, and belonging. Our reports are reviewed by the United Nations Human Rights Commission and the Human Rights Council, and inform the UN’s recommendations to hold the US Government and legislative bodies accountable to their obligations as related to the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), the International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

I. Introduction

This submission is in response to the Request for Early-Warning Measures/Urgent Action Procedures to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, in review of the United States of America and the federal government’s obligation to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). As a signatory to the ICERD, the United States is under an obligation to prohibit and eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms (Article 2, ¶1) as defined by the ICERD. The Convention defines racial discrimination (Article 1, ¶ 1) as distinctions, exclusions, restrictions, or preferences based on race which have “the purpose or effect” of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in any field of public life. The ICERD’s definition of discrimination is unequivocal: effects and racially disparate outcomes caused by individual or institutional practices and policies are of primary concern.

In the United States, racial inequalities and disparities stem from policies and practices that perpetuate structural racialization. Structural racialization is a “set of practices, cultural norms, and institutional arrangements that are both reflective of and simultaneously help to create and maintain racialized outcomes in society.”1 In the context of the US, the outcomes of structural racialization generate and extend preexisting racial and ethnic inequalities that hinder access to equitable services, resources, and opportunities, such as housing, healthcare, drinking water and sanitation, education, economic opportunities, freedoms and rights as enshrined in the US Constitution. As a result, the federal government’s responsibility to provide all its citizens and residents with equal access to adequate life opportunities requires the establishment of a more holistic and equitable treatment in the design of public policy and implementation.

Although racism in the United States is often viewed as a product motivated by individual racial animus, racial inequalities and disparities are ultimately a byproduct of structural racialization, institutionalized by way of policies and practices at the local, state, and federal levels. The three case studies provided in this submission—addressing issues related to water security, housing policy, and Islamophobic measures and policies—offer evidence of the ways in which unjust structures ultimately perpetuate racial and ethnic inequalities in the United States. The policies, practices, cultural norms, and institutional arrangements that establish the foundations for structural inequalities are reflective of, and continue to perpetuate, the cycle of racialized outcomes that obstruct equal opportunity and access to public health, housing, religious freedom, and unbiased treatment in the US.

Importantly, for the US to maintain its commitments to the ICERD, as well as to strengthen its efforts to eliminate all forms of racial and ethnic discrimination, the federal government needs to ensure equitable access—regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or religious beliefs—to social, political, economic, legal, and health related rights and opportunities. This applies to private and public spaces, institutions, government bodies, and programs that implement policies, and practices that have historically disenfranchised, and continue to disenfranchise, people of color, low-income communities, people with disabilities, and other social groups by way of providing unequal treatment and access to fundamental rights. These rights include access to clean water and water sanitation, appropriate housing, as well as freedom of religion, and freedom from discrimination. As such, the executive and legislative authorities are obliged to examine and restructure the ways in which opportunities and resources are provided to the American public. This includes enhancing coordination between federal, state, and local governing bodies to ensure that both targeted and universal interventions are implemented to eliminate racial and ethnic inequalities and discriminatory practices.

The issues addressed in this submission reference the United States’ failure to uphold ICERD Article 2 and Article 5, and evidence how structural inequalities and discriminatory practices are preventing equal access to drinking water and wastewater services, housing, as well as the right to freedom of religion, and freedom from discrimination.

II. Water Security

Affordable Drinking Water and Wastewater Services

Studies have found that areas where people most often experience affordability barriers to accessing water and sewage systems are also areas where there are higher populations of people of color, people in poverty, disabled people, and people with higher rates of enrollment in public service programs.2 These “pockets of water poverty” are consistently characterized in this way. A notable demonstration of this national trend is the regional drinking and wastewater system in southeast Michigan—notable because of the extreme scale of water shutoffs in the city of Detroit and the shifting of the drinking water system away from the regional system in the city of Flint.3

In a United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) study of 795 utilities, 228 utility services offered some form of affordability plan—only 28 percent of the sample.4 Households struggling with affordability are underrepresented in institutions that determine rate structures and other procedures for utilities. These are the same groups that are on the lower side of a number of disparities—in income, wealth, and in political power. Public utilities are natural monopolies that function with ostensibly neutral and objective processes that are universal and “colorblind” with the intention to treat everyone the same. In execution, these universalist policies often perpetuate disparities and end up providing greater outcomes to the groups that are already better served by dominant institutions. The case of southeast Michigan is instructive in this context. If the southeast system’s administration fails to create a targeted rate structure and adequate affordability programs—and if the administration pursues universal policy to treat municipal retail customers and system users with the same brush, it will neglect important differences and fail to respond adequately and fairly to the different ways some places and groups of people relate to their water and sewer services. Such a failure will not only perpetuate households’ water poverty, but will also increase water insecurity throughout the system. The cascading effects of water poverty will undermine public health and environmental quality throughout the region.

Fundamentally, water shutoffs due to an inability to pay the cost of service signal a structural problem. These structural problems include design flaws in local service rate structures and affordability programs. However, a decade of government cuts in funding for public services and widening racial wealth and income inequality have weakened the capacity for local governments to sustain effective rate and affordability programs. This is particularly the case in the aftermath of the Great Recession,5 beginning in 2008, from which many places have yet to recover.6

Public financing of local drinking and wastewater systems falls disproportionately to local governments and the public utility.7 Local governments provide 98 percent of public investment in the nation’s water and sewer systems.8 The federal government is funding only one-third of the nation’s water utility capital needs, estimated to be $123 billion per year over the next 10 years.9 The great demand for investment is clear and many utility systems face difficulty in financing the necessary improvements. The extreme needs for revenue and investment can be hindered by some circumstances that are increasingly common across the US—unfair fees or credit ratings associated with municipal bond markets, declining population numbers in service areas, and decreasing household financial health.

The spread of residential water shutoffs as an incentive to pay assumes that households can afford to pay. Residential water bills have risen consistently since 2010—and annual increases have varied between 3 percent and 9 percent.10 Between 2010 and 2015, there was an overall 41 percent rise in bills for both water and sewer utility services.11 The majority of residential water shutoffs are due to arrears accumulated by households’ inability to pay, not a lack of willingness to pay or the “free rider problem” as articulated in neoclassical economics.12 Water and sewer utilities in the US are considered natural monopolies and rate setting is typically dominated by studies that measure users’ willingness to pay (WTP) for water. However, as wealth, wage, and income inequality accelerates across the US, rates for water and sewer utilities set according to WTP13 is entirely mismatched to the empirical reality that shows some people are simply unable to pay.14 These studies have also shown that lower income households are most sensitive to increasing water rates—meaning that if there are any changes in the rates these are the households most likely to use less. In the context of extreme austerity and a lack of federal funding, the dominant cost recovery rate setting model neglects the profound role of water and sewer utilities in public health and other cascading effects inaccessibility can create.15

Physiological Health Effects of Inaccessible Drinking and Waste Water

Water shutoffs can threaten public health16 and exacerbate or deepen racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes. Studies overwhelmingly confirm the links between water scarcity and a variety of health issues.17 The link between living without access to drinking water or wastewater services and vulnerability to a number of illnesses is well-documented and studied with consistent findings across the globe.

A primary risk associated with water scarcity is dehydration. It can have lasting effects on individuals’ health, including intensifying existing health problems. Moreover, poor hygiene resulting from lack of water access can spread and create a variety of health problems, such as skin diseases and gastrointestinal issues, as handwashing is the first line of defense against several communicable diseases. Lacking water in the home can also negatively impact nutrition, as the preparation of healthier foods is particularly dependent upon water.

In the case of Detroit, there is little scholarly study of the effects of water shutoffs and public health, although there is an abundant body of knowledge on the effects of access to water and the health impacts of water insecurity. An abstract of an unreleased study by the Henry Ford Health System’s Global Health Initiative offers a preliminary analysis of the effects of shutoffs on public health in Detroit. The study examined 37,441 cases of water-related illnesses at Henry Ford Hospital between January 2015 and February 2016. Researchers found that patients with water-related illnesses were 1.48 times more likely to live on a block that had experienced water shutoffs.18 These findings are consistent with the large body of literature of drinking water and wastewater insecurity globally.

There are also a variety of mental health issues associated with water poverty, and water deprivation can exacerbate existing mental health problems as well.19 For example, irregular bathing and sanitation can lead to anxiety as well as other forms of emotional distress, and can create lasting feelings of shame and negatively affect people’s sense of self-worth. In these ways and others, the suspension of residential drinking water and wastewater services creates lasting mental and physical stress for individuals that has measurable effects on the body. The “toxic stress” associated with the cascading effects of shutoffs must be considered when appraising the health costs of water deprivation.

A variety of studies have discussed the way in which toxic stress contributes to disparate health outcomes for people20 —in particular for poor people and people of color.21 The day-to-day stressors of living as a person who is considered “other” and deprived of resources and opportunities have demonstrable physiological effects. This chronic stress may be related to experiencing microaggressions, persistent unemployment, residential segregation, and subpar educational options. While studies have not explicitly examined the relationship between toxic stress and water scarcity, the connection is plausible. This is especially true when considering the way in which water access is a precondition for other negative outcomes associated with “toxic stress” and increased allostatic load, a term used to describe physiological effects of long-term exposure to stressful experiences that change the body’s production of particular hormones. Triggers for increased toxic stress and negative impacts on individual allostatic load include maintaining family cohesion, housing, healthy food, and health.

Additionally, as Child Protective Services (CPS) considers homes without access to running water to be unfit environments for children, water shutoffs can break up families.22 Whether or not the child is actually removed from the house, living with the possibility of separation creates psychic harm and contributes to an individual’s allostatic load. Living as a child without stable and consistent access to water constitutes an adverse childhood experience, and studies of adverse childhood experiences have been shown to correlate with deleterious lifelong physical health outcomes, demonstrating the increase in risk for future problems as related to health and access to opportunity.23

The Impact of Drinking and Waste Water on Social Determinants of Health and Housing

Water access is a precondition of human health, and depriving people of it constitutes a violation of basic human rights. Not only are marginalized groups disproportionately exposed to health risks, but they also often have limited access to health care. These social determinants of health—that is, increased exposure to risk and limited access to care—combine to perpetuate disparate outcomes.24 The wide-ranging health consequences of water deprivation endangers the well-being of individuals, families, and entire communities.

Past due water and sewer service bills are often associated with housing insecurity. In many cities, past due bills can be placed as a lien on a home. These liens accelerate the path to foreclosure. In many cities where the foreclosure crisis still looms large, any additional ingredient leading to foreclosure makes one’s housing precarious.25 In Detroit, research has documented the ways that past due amounts on delinquent water bills are rolled over to liens on homes. This lien can then combine with any other liens and therefore accelerate the process of home foreclosure.26 Foreclosures have a number of negative outcomes for households and communities at large.

Across the US, there are similar problems with the use of shutoffs to increase system revenue from people who cannot pay and a lack of mechanisms to appeal or suspend a shutoff. In the course of our research we have not found any appeal process that effectively prevented a shutoff in the case of an inability to pay—although we did find examples of income-based repayment plans and other arrangements for short-term or one-time reductions. Interviews with people who have had their drinking water shut off demonstrate that many repayment or installment plans do not offer terms that are affordable for residents.

Upscaling the federal government’s investment in the nation’s water and sewer systems can have a macroeconomic expansionary effect.27 The federal government could close the gap between its current investment in drinking and wastewater infrastructure, and the government’s measure of what is necessary over the next 10 years. If the estimated investment gap were closed, it would result in over $220 billion in total annual economic activity to the country. Once established, these investments would generate and sustain approximately 1.3 million jobs over the next 10-year period. Furthermore, the value of safe provision, delivery, and treatment of water to customers results in significant avoided costs for businesses that would otherwise have to provide their own water supplies. These investments would save US businesses approximately $94 billion a year in sales in the next 10 years and as much as $402 billion a year from 2027 to 2040.28

Addressing Water Security and Structural Inequalities through Federal Government Investments

Federal investments should be made, but should also be designed to ameliorate the consequences of structural racism within the US. Designing the scale and scope of large investments can be informed by the funding program’s impact in perpetuating structural racism in the US. In this respect, it is instructive to consider the structural racial implications of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA).29 The ARRA stimulus was among the largest undertaken by the nations belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, helping to pull the US economy out of the ditch of recession. The many programs and subsidies that composed the stimulus provided a laboratory for analysis of policy formulation and implementation.30 The ARRA program is widely thought to have contributed to economic stability in the aftermath of 2008’s economic crisis. However, the program was not designed in such a way that the funding package was also able to address the legacy of structural racialization in the US.31

Channeling the funding through existing program design may meet the technical needs of system upgrades, but it will not contribute to addressing fundamental problems of water poverty that are rooted in the legacy of race in the US. The program design would need to be targeted to different places and designed to build capacity at the local level for groups of people who are currently experiencing the harms of poverty. This would include, for example, designing projects to include job training and expanding educational opportunities to prepare unemployed or underemployed workers with the skills required for these projects.32

This type of funding could be accomplished through a massive expansion of the State Revolving Funds (SRF) administered by the EPA and its state-level counterparts. The design of the funding should be targeted to publicly owned, managed, and operated system infrastructures as an effort to increase the multiplier effect in local economies and to ensure that public dollars are not misdirected to subsidize private corporate enterprise that have acquired exceptionally valuable public assets.

Currently, SRF programs funds are not always fully expended on an annual basis. However, this should not indicate that the financial needs of systems in the state are met. Rather, it is often the case that the terms of funding through SRF programs are such that communities are still unable to afford absorbing the costs of a system improvement—even with the help of SRF. This means that the SRF program itself needs to be redesigned, in addition to substantially increasing the amount of funding for SRF programs. The funding available through such an increase should be able to apply to ordinary costs including operation, management, and replacement.

Recommended Questions

- Given the economic stabilizing effect of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and given the positive multiplier effects of federal investment in drinking and wastewater, how will the United States government design similar legislation that address the problems of drinking and wastewater systems while also addressing the legacy of racial harm associated with water poverty, including health outcomes?

- In regards to the federal government’s investment in drinking and wastewater infrastructure, what steps can be taken by the government to make funding available to support the design of rate systems that accomplish goals of cost recovery, conservation, and affordability?

- . What steps can be taken by the federal government to fund and build job training components for drinking and wastewater infrastructure so that a funding increase could better target employment barriers that exist most acutely in Black communities?

Recommendations

- Massively increase federal funding for only publicly-owned, managed, and operated drinking water and wastewater infrastructure across the country.

- Design funding strategies to expand local adaptation to the climate crisis. The climate crisis will greatly impact the needs for water and sanitation systems throughout the US, and climate crisis mitigation efforts are particularly valuable to Black communities within the US.

- Extend funding to users who are not part of a connected water and sewer system. This accounts for people in rural or remote areas who maintain and build their own wells and septic systems, systems which are difficult for households to update and maintain.

III. Housing Equity

The Disparate Impacts of Inequitable Access to Housing

The disparate impact of housing instability, unaffordability, and access to housing on people of color in the United States is a violation of Article 5 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The concerns previously raised by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination - the persistence of racial discrimination in access to housing, the high degree of racial segregation and concentrated poverty, and discriminatory mortgage lending practices - remain not just inadequately addressed, but even more pressing amidst current crises of involuntary residential displacement and homelessness that disproportionately impact communities of color. Across the US, a lack of affordable housing and adequate protection of tenants’ rights is stripping communities of color of their wealth, harming health and well-being, restricting access to opportunities and resources, generating new patterns of racial and economic segregation, and further entrenching existing racial inequity.

The market and existing public policy do not offer adequate solutions to these injustices, and government has not only failed to protect and provide for those affected, but continues to facilitate racial inequality through laws that encourage the unfettered commodification of housing, which directly undermine the right to an affordable, safe, and stable home.

Racial Disparities in Access to Homeownership, Affordable Rental Housing & Homelessness

In the United States, access to housing, as well as the material benefits of property ownership, remain deeply racialized. As of 2017, white households have significantly higher homeownership rates than all other racial groups (72 percent - compared to 41 percent of Black households, 54 percent of American Indian or Alaska Native households, 60 percent of Asian households, 41 percent of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 47 percent of Latinx households).33 Differential access to homeownership across generations is both a consequence and driver of a widening racial wealth gap. According to a January 2019 report by the Institute for Policy Studies, the median wealth of Black families is $3,600, and the median wealth of Latino families is $6,600 - compared to $147,000 for white families (equivalent to just 2 percent and 4 percent of the median wealth of white families, respectively).34 Furthermore, 37 percent of Black families and 33 percent of Latinx families have zero or negative wealth, compared to just 15.5 percent of white families.35

With homeownership out of reach for many, people of color comprise the majority of the US renter population and are disproportionately affected by the insecurity and lack of affordability facing tenants. Black and Latinx renter households face higher rates of housing cost burden (55 percent and 54 percent) than their white counterparts (43 percent).36 Many face impossible choices - choosing between rent or other necessities like food and healthcare; accepting an extreme rent increase or moving far away, only to spend hours commuting to work; or moving into inadequate or unsafe spaces - often leaving them one unexpected rent hike or additional financial expense away from eviction, displacement, or homelessness. The disparate impact of homelessness on people of color is extreme; according to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), four in ten people (219,809 individuals) experiencing homelessness in 2018 were Black, “considerably overrepresented compared to their share of the US population, 13 percent.” By comparison, HUD notes, “while comprising nearly half of the homeless population, people identifying as white were underrepresented compared to their share of the US population (72 percent).”37

US Government (In)Action Undermining the Equal Right to Housing

Despite the well-documented racial disparities in access to affordable housing, the United States government has reversed much of its progress toward advancing fair housing and the overall right to housing that was reported on in its 2014 report to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

In 2018, US Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson halted the implementation of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule (AFFH), which was only first finalized in 2015 under the administration of President Barack Obama to clarify the responsibility of all levels of government in implementing the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The federal administration has also advocated to further diminish federal investments in affordable and public housing programs that have already been severely underfunded for decades, which is part of a broader budgetary proposal that policy experts from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities state “would make poverty more widespread, widen inequality and racial disparities, and increase the ranks of the uninsured.”38

At the same time, the US government has facilitated the financialization of housing - the treatment of housing as a commodity, investment vehicle, and means of extracting profit, rather than a home and a right - through corporate deregulation, tax breaks and incentives to property owners and Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), and direct fiscal support to private equity firms.39 This directly limits availability of affordable housing supply and promotes instability40 and unaffordability for renters, while increasing wealth of property owners and corporate investors.41

In their March 2019 letter to the US Government, Leliani Farha, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, and Surya Deva, the Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group on Business and Human Rights, point out that the financialization of housing has disparately impacted Black households and neighborhoods. They note that corporate landlords are concentrating their property acquisitions in neighborhoods of color, with some of their highest levels of activity in communities that are over 70 percent African-American.42 Enabling this model, which involves acquiring “undervalued” and/or foreclosed homes, maximizing profits through constant rent increases, and aggressively evicting tenants who are often unable to afford the increased housing costs, directly contradicts the government’s obligation under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.43

This discriminatory system relies upon the vulnerability of tenants, which exists in many cases through government inaction. Instead of proactively safeguarding the right to housing, many states are actually preventing local jurisdictions from taking action themselves. For example, the Local Solutions Support Center reports that 31 of 50 states have some form of legislation that either prohibits or limits local governments’ ability to regulate residential rents,44 and the national government has failed to encourage these states to shift course.45

All levels of government have also failed to adequately respond to the human rights concerns raised regarding the treatment of individuals experiencing homelessness. In a September 2018 report to the UN General Assembly, the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing documented the “cruel and inhuman treatment” of individuals living in US encampments in San Francisco and Oakland, California, who have been denied access to water, sanitation, and basic services in attempts to discourage them from residing in encampments. She noted that this is a “violation of multiple human rights, including the rights to life, housing, health and water and sanitation.” US cities have also criminalized people experiencing homelessness for conducting basic human functions like sleeping and sitting in public places, which both the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing46 and the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights highlight as serious human rights concerns.47

Prioritizing housing as a human right is essential to achieving racial justice. This will require greater commitment by the national government as well as leadership in coordinating with local, regional, and state governments. Through its failure to protect tenants, ensure the dignity of people experiencing homelessness, and affirmatively pursue equitable access to homeownership, the US government currently falls short of its obligations to prohibit and eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction to race, to enjoy the right to housing under Article 5 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Recommended Questions

- . How will the United States government address the growing housing affordability crisis affecting renters throughout the country to ensure that its impacts are not in conflict with the United States’ obligation under the ICERD?

- What specific actions will the United States government take to effectively enforce the national Fair Housing Act of 1968 and continue the implementation of the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule?

- What actions will the United States government take to protect the human rights of all people experiencing homelessness, and more specifically, what targeted approaches will be taken to address the disproportionate impact of homelessness on African Americans?

Suggested Recommendations

- . That the United States government reform national fiscal priorities and tax code in order to promote the stability of tenants, the use of housing as a place to live rather than a commodity, and equitable distribution of public goods and services.

- That the United States government work with state and local governments to protect tenants from exploitative practices of landlords in the rental housing market, including unjust evictions and rent increases beyond fair market return.

- That the United States government prohibit policies that criminalize people experiencing homelessness, and invest in the expansion of social housing - including public housing, community land trusts, and non-profit housing - to ensure that an adequate supply of affordable housing exists for those left out of the market.

IV. Discriminatory Impacts of Islamophobia

The Rise of Islamophobia in the United States

The current political climate in the United States reflects a new reality influenced by a populist leadership that colludes with a reemergence of white supremacy.48 Contemporary political conditions, political rhetoric, state legislation, and government policies are being used to drive a wedge between indigent working-class white people and people of color, while simultaneously increasing fearmongering,49 xenophobia, and anti-Muslim sentiment50 in US society. Collectively, the conditions of economic austerity, as well as the perceived threat and anxiety of a changing demographic, and the growing influence of white nationalist and extreme right movements in the US, have conveniently led to the scapegoating of immigrants and minority populations for economic and social instabilities.51 Consequently, many individuals and groups in the US have been engaged in hostile behavior toward the other in order to preserve an imagined “American” way of life.

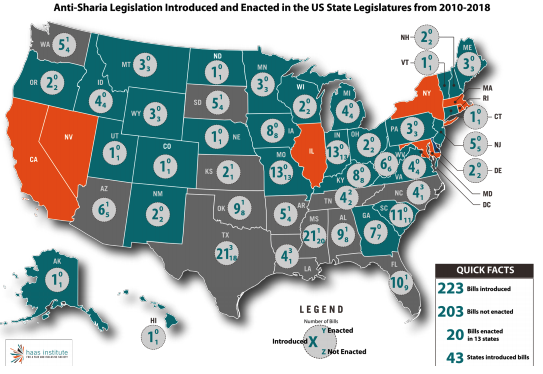

The campaign rhetoric of President Donald Trump, in which he called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”52 and the multiple executive orders known as the Travel Ban, along with the undercurrent of religious and racial anxieties motivated and manipulated by political and cultural leaders, has led to the intensification of anti-Muslim sentiment and Islamophobia in the US. The disparate impacts of Islamophobia range from attempts to undermine Muslim Congresswomen Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib,53 to ushering in anti-Muslim policies at the state and federal levels, such as 223 anti-Sharia bills and President Trump’s Travel Ban. Importantly, these federal and state policies undermine the civil and constitutional rights of Muslims in the United States and compromise the US government’s compliance with the ICERD, notably Article 2, ¶1(c), and Article 5 (d)(vii).

For nearly two decades, and spanning three US presidencies, the federal government, states, and local authorities have infringed on the religious freedoms of its Muslim citizens and lawful residents by enacting policies and practices that disproportionately discriminate against Muslims. These policies subject Muslims to unwarranted surveillance, profiling, exclusion, and discrimination along the lines of race, ethnicity, national origin, and religion.54 President Trump has continued this legacy by emboldening white nationalists and refusing to condemn white supremacy, as evidenced by his response to the Charlottesville “Unite the Right Rally” in 2017 and the Christchurch mosque shootings in 2019, while bolstering anti-Muslim and xenophobic policy proposals at both the federal and state levels.55 This is further substantiated by the 2017 Presidential Proclamation 9645, known as the Travel Ban or otherwise referred to by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and others as the Muslim Ban,56 and is the newest addition to the list of 15 federal measures that attempt to legalize discrimination against Muslims.57 The Travel Ban clearly demonstrates the US government’s violation of its international human rights obligations as the ban disproportionality discriminates against Muslims on the basis of race, religion, and national origin.58

Perhaps one of the most evident markers of increased Islamophobia at the structural level is the rise of anti-Sharia legislation in the US. Since 2010, the increase of anti-Sharia legislation in the US state legislatures has served to violate the rights of Muslim Americans,59 as the laws violate religious freedom as afforded by the First Amendment of the US Constitution and unnecessarily prevent Sharia from being invoked in US courts. Furthermore, the development of organized anti-Muslim efforts and the rise of contemporary Islamophobia in US state legislatures through the collusion of state lawmakers and anti-Muslim activists, portrays Muslims and Islam as both incompatible with, and a threat to, American values. This serves as an indicator that the US government is complicit and failing to adhere to its own obligations under the ICERD as well as ICCPR. As noted in the Human Rights Committee’s Concluding Observations from 2014, the Committee observed that the federal government needs to “give greater effect to the Covenant at federal, state, and local levels, taking into account that the obligations under the Covenant are binding on the State party as a whole.”60

Current US Federal Government Policy and Practice

The US government and state lawmakers have spurred anti-Black, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, and anti-refugee grassroots mobilizations and legislation at an unprecedented level, which has further increased racial prejudice and animosity on the ground.61 For example, on September 24, 2017, President Trump announced the third version of the Travel Ban,62 or what is commonly known as “Muslim Ban 3.0,” which varied from the previous executive orders in regards to the list of banned countries and the immigrant and non-immigrant visa restrictions for those countries.63 The current version of the Travel Ban indefinitely restricts travel to the United States for nationals of seven countries: Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. Five of the seven countries are identified as Muslim majority countries. The nationals of each country are subject to specific country-by-country travel restrictions as is outlined in the Proclamation,64 with exceptions and waivers established by the Proclamation.65

On June 26, 2018, the US Supreme Court upheld the Presidential Proclamation 9645 by a 5-4 vote in the case Trump v. Hawaii. The Travel Ban has received widespread criticism, and a number of UN human rights experts have expressed deep concerns regarding the Executive Order.66 In the most recent round of hearings, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the Supreme Court’s ruling on the ban, stating that “the Proclamation was motivated by hostility and animus toward the Muslim faith” and went on to highlight that the Travel Ban “now masquerades behind a façade of national-security concerns.”67 In her sharp dissent68 Justice Sotomayor drew parallels between the Trump v. Hawaii decision and the case of Korematsu v. United States, 69 the notorious ruling that upheld the detention of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

The numerous iterations of the Travel Ban have made longstanding US immigration laws invalid by creating unwarranted chaos and obstacles for US citizens and lawful permanent residents (LPRs or Green Card holders) to reunite with family members.70 The current Travel Ban restricts more than access and ability to travel, as it endangers the benefits that US citizens and LPRs enjoy by indefinitely separating families, forcing family members to await reunification in conflict zones or other precarious situations, where health, education, and economic stability are compromised.71 As a result, these statutory protections and benefits are no longer available to the majority of US citizens whose family members come from the above-mentioned five Muslim-majority countries.73 Furthermore, the ban circumvents US immigration law, which forbids discriminatory practices, such as nationality-based discrimination, when considering the issuance of immigrant visas.73

For these nationals, the Proclamation provides few exceptions to the Travel Ban restrictions, and the only option available for most new and existing applicants to travel to the United States is through a waiver process.74 The Proclamation contains a waiver provision that specifies authority to consular officers and Customs and Border Protection officials to, at their discretion, grant visa waivers to the Travel Ban on a case-by-case basis for individuals otherwise blocked from entry to the US.75 To qualify for a visa waiver, the applicant must demonstrate to the consular officer or Customs and Border Protection official that: 1) denying entry would cause undue hardship; 2) entry would not pose a threat to national security; and 3) entry would be in the national interest.76 The visa waiver provision has received much condemnation, and several civil rights groups, private citizens, and members of Congress have petitioned the administration to release more information regarding the opaque implementation of the Proclamation’s waiver provision.77

A case in point, which drew international criticism and attention to the validity of the Travel Ban and the visa waiver process was a 2018 lawsuit filed by the Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) on behalf of Shaima Swileh, a Yemeni woman who sued the Trump administration to enter the US and be reunited with her husband and two-year-old son, Abdallah Hassan. Abdallah was receiving medical treatment in the US for a terminal genetic brain disorder. Swileh and her husband, Ali Hassan, a US citizen, were married in Yemen, and in 2016 the couple fled to Egypt to escape the war when their son was eight months old. Since 2017, the couple had been trying to get a visa for Swileh so the family could relocate to the US with their son, whose health was deteriorating.78 In 2018, Ali Hassan brought their son to the US for much needed medical treatment, but Swileh was barred from entering the US due to President Trump’s Travel Ban. Swileh applied for a visa waiver and waited more than a year to receive a decision for her request.79 She was later granted a visa following the emergency federal lawsuit filed by CAIR on her behalf against the US government and arrived to the US with only a matter of days to spend with her son before his death.80 The CAIR lawsuit documented how the US embassy ignored over 28 pleas and attempts for help regarding her request for a visa waiver, including requests filed by the family’s previous attorney to expedite her case, which evidenced medical documentation showing the severity of her son’s illness.81

The UN Human Rights Committee, in their recently-released “List of issues prior to submission of the fifth periodic report of the United States of America,” specifically asks the United States government to address the ability of individuals to obtain visas under the Travel Ban, as well as to address the visa-waiver process, which has a rejection rate of 98 percent.82 The Committee also requests that the US Government indicate how the Travel Ban is congruous with the non-discrimination and nonrefoulement stipulations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.83

Current US State Legislatures’ Policies and Practices

Still, discriminatory, anti-Muslim sentiment and policy is not limited to the US federal government, as has been demonstrated by the rise in anti-Muslim state legislation that has spread across the nation. Since 2010 there have been 223 anti-Sharia bills introduced in 43 state legislatures. Of the 223 bills introduced, 20 bills have been enacted into law. In addition to stoking an unwarranted fear of Islam and Muslims, the impacts of the anti-Sharia legislation strip Muslims of their legal rights as afforded by the US Constitution’s First Amendment, as these laws unnecessarily prevent Sharia from being invoked in US courts by preventing state judges from considering foreign laws in their rulings.84 For example, the laws single out Sharia and violate the First Amendment by treating one belief system as suspect, and therefore prohibiting Muslims from the free exercise of their religion to enter into contracts that are enforced by Sharia regarding family law, estate planning, business dealings, and other agreements. What’s more, the ACLU recognizes that anti-Sharia bills are intolerant of those who practice the Muslim faith, and that such legislation creates significant unintended consequences for all Americans that engage in family matters that involve foreign law—such as international marriages and adoptions—and these laws undermine the ability of courts to interpret laws and treaties regarding global business, as well as international human rights.85 The underlying issue is that anti-Sharia legislation threatens the civil and constitutional rights of all Americans,86 as the laws violate religious freedom, undermine the independence of the US courts, alter routine decisions made by courts, and place a blanket prohibition on courts in recognizing foreign or international laws and treaties.87

The only anti-Sharia legislation to have been reversed was the Oklahoma “Save our State Amendment” which was enacted into law in 2010, and later struck down in August 2013 by a federal court.88 The lawsuit, Awad v. Ziriax, that led to this reversal challenged the amendment on the premise that it violated the right to religious liberty as afforded by the Constitution, arguing that the amendment was framing Muslims as religious and political outsiders and imposing restrictions on Muslims that are not faced by any other individuals of faiths.89 To date, it remains the only anti-Sharia act or amendment to have been struck down.90

Recommended Questions

- . How can the United States government ensure that Presidential Proclamation 9645, including the visa waiver provision, is not in conflict with the non-discrimination and non-refoulement provisions of the ICERD?

- How can the United States government ensure that anti-Sharia laws are not in conflict with the US’ obligations under the ICERD?

- What evidence is there to prove that Presidential Proclamation 9645 is protecting US national security, particularly from foreign nationals of the countries listed in the ban?

Suggested Recommendations

- That the United States government immediately rescind Presidential Proclamation 9645 as the federal measure discriminates on the basis of race, religion, and national origin, and separates families; the Proclamation infringes on the human rights of individuals within and outside US territory, disproportionately affecting Muslims and Muslim refugees.

- That the United States government establish a visa waiver process that is compliant with the ICERD and US immigration law, which forbids discriminatory practices, as well as to reconsider cases that were denied the visa waiver and expedite visas to qualifying families and individuals.

- That state governments immediately rescind anti-Sharia legislation that have been enacted into law and implement policies to prevent anti-Sharia legislation from being reintroduced and enacted as the laws are inherently discriminatory and xenophobic and infringe on the constitutional rights of Muslims and non-Muslims within US territory, but disproportionately affecting Muslims.

V. Conclusion

The United States has a responsibility to provide all of its citizens and residents with equitable access to necessary and adequate life opportunities. Within the US, there are groups and individuals who are denied fundamental rights and benefits on the basis of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or religious beliefs. The task of eradicating structural injustices in the US requires a multifaceted approach that must engage strategies and coordination between federal, state, and local governing bodies to address the largest forms of discrimination in the US as related to health and safety, housing, immigration, and freedom from all forms of discrimination.

The issue of water security in the US is one such example in which structural impediments are preventing equitable access to drinking water and wastewater services. “Colorblind” public utilities systems that administer water access operate on universal policies that perpetuate disparities and structural inequalities, providing greater access and benefits to those already well-served by dominant institutions. Such systems fail to create a targeted rate structure and adequate affordability programs that account for important differences in income, physical and mental health, and geographic location, among other factors that determine how some places and groups of people are able to connect to water and sewer services. These structural impediments unnecessarily deprive places, individuals, and families access to water and sewer utilities, which play a profound role in maintaining and sustaining a healthy, thriving, equitable society. Water security is a necessity for human health, and denying people water access constitutes a violation of basic human rights, a violation which the United States government must address and be held accountable to.

Similar to the structural impediments that undermine water security, racial discrimination is pervasive, and persistent, in access to housing in the United States. Prioritizing housing as a human right is essential to achieving racial justice, and in order to prioritize housing as a human right, a greater commitment is required by the US federal government, as well as coordination with local, regional, and state governments to make this right an achievable reality for all. The government’s inability to protect tenants, eradicate homelessness, or at the minimum, to ensure the dignity of people experiencing homelessness, and to establish a system that offers equitable access to homeownership, is preventing the United States from upholding its obligations to prohibit and eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms in accordance with the ICERD.

In addition to water security and housing equity, structural racialization in the United States has enabled the US federal government to institutionalize policies that disproportionately discriminate against, and “other” Muslims. Since 2001, 15 federal programs and initiatives were implemented that target and discriminate against Muslim individuals and communities, the most recent of which is President Trump’s Travel Ban. What’s more, since 2010, 223 anti-Sharia bills have been introduced and enacted across the US. These bills impose barriers that specifically seek to prevent Muslims from engaging fully and freely with their religion by way of preventing Sharia from being invoked in US state courts and by infringing on the rights of Muslims to enter into contracts that are enforced by Sharia. Such legislation and policies are contributing to racialized structures of exclusion in the United States, and are preventing the US from maintaining its obligations in accordance with the ICERD.

To uphold the United States’ obligations under the ICERD, the federal government and its legislative authority need to employ systemic and targeted intervention programs to address structural inequalities and injustices, as well as cease and rescind discriminatory policies and practices that single out Muslims. Such actions are paramount in order to eliminate racial and ethnic inequalities that impede the right to water security, the right to housing, as well as the right to religious freedom, and freedom from discrimination.

- 1john a. powell, “Post-Racialism or Targeted Universalism?,” Denver University Law Review, Vol. 86 (2009).

- 2Elizabeth A. Mack and Sarah Wrase, “A Burgeoning Crisis? A Nationwide Assessment of the Geography of Water Affordability in the United States,” PloS One 12, no. 1 (2017): e0169488.

- 3Joseph Recchie, Anna Recchie, john a. powell, Laura Lyons, Ponsella Hardaway, and Wendy Ake, Water Equity and Security in Detroit’s Water & Sewer District (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2019).

- 4“Drinking Water and Wastewater Utility Customer Assistance Programs,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2016.

- 5“Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, April 23, 2019, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/….

- 6Peter Dreier, Saqib Bhatti, Rob Call, Alex Schwartz, and Gregory Squires, Underwater America: How the So-Called Housing “Recovery” is Bypassing Many American Communities (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society).

- 7Recchie, Recchie, powell, Lyons, Hardaway, and Ake, Water Equity and Security in Detroit’s Water & Sewer District.

- 8Richard F. Anderson, “Local Government Investment in Water and Sewer, 2000 – 2015,” The United States Conference of Mayors, Jan. 10, 2018.

- 9“The Economic Benefits of Investing in Water Infrastructure,” Value of Water Campaign, 2017, p. 2, http://thevalueofwater.org/sites/default/files/Economic%20Impact%20of%2….

- 10Brett Walton, “Price of Water 2015: Up 6 Percent in 30 Major U.S. Cities; 41 Percent Rise Since 2010,” circle of blue, Apr. 22, 2015.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Ruth Lister, “Water Poverty,” Journal of Royal Society of Health 115, no. 2 (1995): 80 – 83

- 13Water Quality: Guidelines, Standards and Health, (London: IWA Publishing, 2001), pg. 339, accessed Mar. 23, 2019.

- 14Guy Hutton, “Considerations in evaluating the cost effectiveness of environmental health interventions,” World Health Organization, 2000, accessed Mar. 23, 2019.

- 15Elizabeth A. Mack and Sarah Wrase, “A Burgeoning Crisis? A Nationwide Assessment of the Geography of Water Affordability in the United States.”

- 16Barry M. Pomplom, Kristen E. D’anci, and Irwin H. Rosenberg, “Water, Hydration, and Health,” Nutrition Reviews 68, no. 8 (2010): 439-458.

- 17Paul R. Hunter, Alan M. MacDonald, and Richard C. Carter, “Water Supply and Health,” PLOS Medicine 7, no. 11 (2010): e1000361.

- 18Alexander Plum, Kyle Moxley, and Marcus Zervos, “The Impact of Geographical Water Shutoffs on the Diagnosis of Potentially Water-Associated Illness, with the Role of Social Vulnerability Examined,” Henry Ford Global Health Initiative, April 8, 2017.

- 19Martina Guzman, “Exploring the Public Health Consequences of Detroit’s Water Shutoffs,” Model D Media, October 6, 2015.

- 20Hollie L. Jones, William E. Cross Jr, and Darlene C. DeFour, “Race-related Stress, Racial Identity Attitudes, and Mental Health among Black Women,” Journal of Black Psychology 33, no. 2 (2007): 208-231.

- 21Jack P. Shonkoff, Andrew S. Garner, Benjamin S. Siegel, Mary I. Dobbins, Marian F. Earls, Laura McGuinn, John Pascoe, and David L. Wood, “The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress,” Pediatrics 129, no. 1 (2012): e232-e246.

- 22Laura Gottesdiener, “UN Officials ‘Shocked’ by Detroit’s Mass Water Shutoffs,” Aljazeera America, October 20, 2014.

- 23Karen Hughes, Mark A. Bellis, Katherine A. Hardcastle, Dinesh Sethi, Alexander Butchart, Christopher Mikton, Lisa Jones, and Michael P. Dunne, “The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” The Lancet 2, no. 8 (2017): e356-e366.

- 24Kevin Fiscella and David R. Williams, “Health Disparities based on Socioeconomic Inequities: Implications for Urban Health Care,” Academic Medicine 79, no. 12 (2004): 1139-1147.

- 25“Mapping the Water Crisis: The Dismantling of African-American Neighborhoods in Detroit: Volume One,” We the People of Detroit Community Research Collective, accessed March 23, 2019.

- 26Ibid.

- 27The Economic Benefits of Investing in Water Infrastructure, Value of Water Campaign, 2017.

- 28Ibid.

- 29Jason Reece, Matt Martin, Christy Rogers and Stephen Menendian, ARRA & the Economic Crisis – One Year Later: Has Stimulus Helped Communities in Crisis? (Columbus: Ohio State University, 2010), accessed Mar. 29, 2019.

- 30Timothy J. Conlan, Paul L. Posner and Priscilla M. Regan, Governing Under Stress: The Implementation of Obama’s Economic Stimulus Program, (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2017).

- 31Jason Reece, Matt Martin, Christy Rogers and Stephen Menendian, ARRA & the Economic Crisis – One Year Later: Has Stimulus Helped Communities in Crisis?

- 32Ibid.

- 33U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2017 One-Year Estimates, Tables B25003B-B25003I.

- 34Chuck Collins, Dedrick Asante-Muhammed, Josh Hoxie, and Sabrina Terry, Dreams Deferred: How Enriching the 1% Widens the Racial Wealth Divide (Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies, 2019), accessed April 22, 2019.

- 35Ibid.

- 36“Renter Cost Burdens by Race and Ethnicity (1B),” Joint Center on Housing Studies of Harvard University, accessed April 22, 2019.

- 37US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development, The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress (Washington, DC: 2018), page 10, accessed April 22, 2019.

- 38Paul Van de Water, Joel Friedman, and Sharon Parrott, “2020 Trump Budget: A Disturbing Vision,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 11, 2019.

- 39Surya Deva and Leilani Farha to the United States of America, March 22, 2019, https://www.ohchr.org/ Documents/Issues/Housing/Financialization/OL_USA_10_2019.pdf.

- 40Elora Lee Raymond, Richard Duckworth, Benjamin Miller, Michael Lucas, and Shiraj Pokharel, “From Foreclosure to Eviction: Housing Insecurity in Corporate-Owned Single-Family Rentals.” Cityscape 20, no. 3 (2018): 159- 88. This study of Fulton County, Georgia finds that large corporate owners of single-family rentals are 68 percent more likely than small landlords to file eviction notices even after controlling for past foreclosure status, property characteristics, tenant characteristics, and neighborhood.

- 41ACCE Institute, Americans for Financial Reform, and Public Advocates, Wall Street Landlords turn American Dream into a Nightmare (Los Angeles, CA: 2018), accessed April 24, 2019.

- 42Deva and Farha to the United States of America, 2019.

- 43Ibid.

- 44“State Preemption of Local Equitable Housing Policies,” Local Solutions Support Center, accessed April 24, 2019.

- 45Deva and Farha to the United States of America, 2019.

- 46Leilani Farha, Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context (United Nations General Assembly, 73rd session, 2018).

- 47Philip Alston, “Statement on Visit to the USA, by Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, December 15, 2017.

- 48“Transcript of Donald Trump’s Immigration Speech,” The New York Times, Sept. 1, 2016, accessed Jan. 5, 2019

- 49Rachel M. Gillum, “Assessing – And Reducing – Public Fear of Muslims,” Scholars Strategy Network, May 22, 2018, accessed Jan. 10, 2019.

- 50Katayoun Kishi, “Assaults against Muslims in U.S. surpass 2001 level,” Pew Research Center, Nov. 15, 2017, accessed Jan. 11, 2019.

- 51Ian Haney Lopez, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class (Oxford University Press, 2014), 147-158.

- 52Jenna Johnson, “Trump calls for ‘total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States’,” The Washington Post, Dec. 7, 2015, accessed Jan. 10, 2019.

- 53John Eligon, “Unchecked ‘Hate’ Toward Rep. Ilhan Omar Has American Muslims Shuddering,” The New York Times, April 25, 2019.

- 54Islamophobia is recognized as a form of xenophobia and discrimination based on religious and national origin that aims to single out, exploit, and exclude Muslims. This belief forms the basis of a distorted ideology that views Muslims and Islam as inferior to Judaism and Christianity, as well a threat to “Western” civilization.

- 55Amanda Sakuma, “Hate crimes reportedly jumped by 226 percent in counties that hosted Trump campaign rallies,” Vox, March 24, 2019, accessed April 29, 2019.

- 56“Coalition Letter Requesting Muslim Ban Hearings in 116th Congress,” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed Jan. 10, 2019.

- 57Rhonda Itaoui and Basima Sisemore, “Trump’s travel ban is just one of many US policies that legalize discrimination against Muslims,” The Conversation, Jan. 29, 2018, accessed Jan. 5, 2019.

- 58“The Muslim Ban: Discriminatory Impacts and Lack of Accountability,” Center for Constitutional Rights, Jan. 14, 2019.

- 59Elsadig Elsheikh, Basima Sisemore, Natalia Ramirez Lee, Legalizing Othering: The United States of Islamophobia (Berkeley, CA: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, 2017).

- 60“Human Rights Committee Concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of the United States of America,” United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, April 23, 2014.

- 61Carlo A. Pedrioli, “Constructing the Other: U.S. Muslims, Anti-Sharia law, and the Constitutional Consequences of Volatile Intercultural Rhetoric (2012),” Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal, Vol. 22, (2012): 65- 108.

- 62Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry into the United States by Terrorists or Other Public-Safety Threats (Third Muslim Ban), Proclamation No. 9645, Sept. 27, 2017.

- 63“Timeline of the Muslim Ban,” American Civil Liberties Union – Washington, accessed Jan. 7, 2019.

- 64“U.S. Supreme Court Ruling On Muslim Ban 3.0 What You Need to Know,” Advancing Justice-Asian Law Caucus and CAIR California, June 26, 2018.

- 65“Timeline of the Muslim Ban,” American Civil Liberties Union – Washington.

- 66“US travel ban: “New policy breaches Washington’s human rights obligations” – UN experts,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Feb. 1, 2017, accessed Jan. 10, 2019.

- 67Harold Hongju Koh, “Symposium: Trump v. Hawaii—Korematsu’s ghost and national-security masquerades,” Supreme Court of the United States Blog, June 28, 2018, accessed Jan. 7, 2019.

- 68Catie Edmondson, “Sonia Sotomayor Delivers Sharp Dissent in Travel Ban Case,” The New York Times, June 26, 2018, accessed Jan. 7 2019

- 69“Facts and Case Summary—Korematsu v U.S.,” United States Courts, accessed Jan. 7, 2019.

- 70Window Dressing the Muslim Ban: Reports of Waivers and Mass Denials from Yemeni-American Families Stuck in Limbo (New Haven, CT: Center for Constitutional Rights and the Rule of Law Clinic at Yale Law School, 2018), 8, accessed Jan. 6, 2019.

- 71Ibid.

- 73 a b Ibid.

- 74Ibid., 9.

- 75Ibid.

- 76Proclamation No. 9645.

- 77Sirine Shebaya, Nimra Azmi, Diala Shamas and Noor Zafar, “Re: Freedom of Information Act Regarding the Waiver Process Provided for in Presidential Proclamation 9645,” letter submitted on behalf of Muslim Advocates and the Center for Constitutional Rights, Jan. 23, 2018, accessed Jan. 7, 2019.

- 78“Two-year-old son of Yemeni woman who sued to enter US dies in California,” The Guardian, Dec. 29, 2018, accessed April 26, 2019.

- 79“Yemeni mother wins visa fight to see dying son in US, lawyer says,” AlJazeera, Dec. 18, 2019, accessed April 26, 2019.

- 80Ibid.

- 81Ibid.

- 82“List of issues prior to submission of the fifth periodic report of the United States of America,” Human Rights Committee, April 2, 2019, accessed April 26, 2019.

- 83Ibid.

- 84Abed Awad, “The True Story of Sharia in American Courts,” The Nation, June 14, 2012, accessed Jan. 7, 2019.

- 85“Oppose – HB 419: The Anti-Sharia Law Bill,” The American Civil Liberties Union – Idaho, Jan. 31, 2018, accessed Jan. 10, 2019.

- 86Baher Azmy (Legal Director, Center for Constitutional Rights), interview by Basima Sisemore, June 16, 2017

- 87Daniel Mach and Jamil Dakwar, “Anti-Sharia Law: A Solution In Search Of A Problem,” Huffpost, May 20, 2011, accessed April 26, 2019.

- 88Ian Millhiser, “Sorry, Oklahoma—Federal Court Says State Cannot Write Anti-Islamic Bigotry Into Its Constitution,” ThinkProgress, August 16, 2013, accessed Jan. 7, 2019.

- 89Plaintiff-Appellee Awad’s Response Brief, in the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, Appellate Case Number 10-6273, at 18.

- 90Abed Awad (Attorney and Adjunct Professor at Rutgers University School), interview by Basima Sisemore, June 20, 2017.