Download a PDF of this report here

Summary

What does it mean to really belong in Richmond? How do our homes shape how we think of who belongs? What solutions and actions are needed to achieve a city where everyone belongs? The stories, poetry, data, images, and policies that make up this report center on these questions.

“To describe housing without understanding belonging is to speak of statistics without people, place without human texture, buildings not homes,” we write in our conclusion. Arts and poetry bring us closer to understanding what is truly at stake when we talk about homes and the housing crisis. Ciera-Jevae Gordon writes in her original poem that:

... having a home is essential

And I ain’t got one

It’s a human right

but do they even think I’m human?

(Find many other pieces from Ciera-Jevae Gordon created as part of the Staying Power fellowship in this book of poetry here)

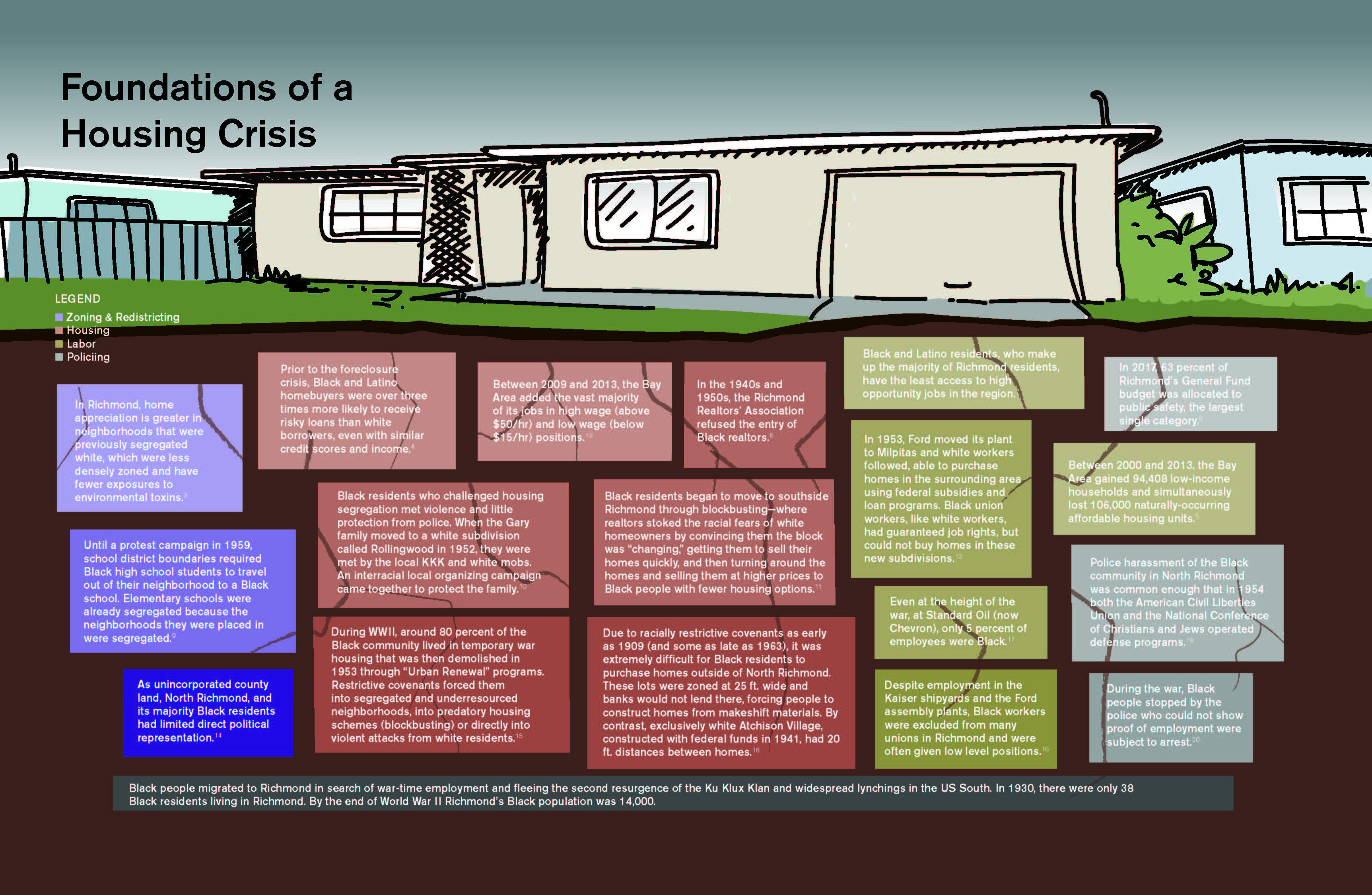

Like this poem, much of the research and creative development of this report was done by the Staying Power Fellows, a group of Richmond residents impacted by the housing crisis who over the past year carried out interviews, analyzed data, read reports and analyzed their own experience. For example, the Foundations of the Housing Crisis diagram comes out of a root-causes analysis that the fellows developed. Fellow Noe Gudino researched the Source of Income Discrimination policy, which lead to the concept of a Reusable Tenant Screening Report. From their research, the fellows wrote and publicly performed poetry, developed a large public mural, drafted policies, and are sharing all of this work with their communities. Sasha Graham-Croner’s preface to the print version of the report provides a powerful framing for the need for leadership and research led by people directly impacted by the housing crisis.

The research in this report also comes from the insights and ongoing work of many Richmond-based organizations and other residents. On June 3, 2017, eight organizations co-sponsored a Citywide Housing Symposium, where over 100 participants discussed housing issues in Richmond and policies to address them. Public spaces for community leaders working on these issues have also been a source and a sounding board for the research, including the GRIP Social Justice Forum and the Richmond Progressive Alliance Housing Action Team.

A rigorous research process that begins with supporting people most impacted by the issues to design and carry out their own analysis, and connects with community-based organizations that organize residents to collectively advocate for themselves, makes for more responsive housing decisions and begins to reverse the power imbalances that perpetuate homelessness, lack of affordability, and other issues. Responsiveness to everyone’s wellbeing must be at the heart of change, as fellow DeAndre Evans writes in one of his poems:

…No one is responsive, feels like I’m talking to myself

When help is asked to restore something simple as a lock on a gate

So I can feel safe

Recognizing that there is no single solution or silver bullet to the housing crisis affecting so many not only in Richmond, but nationwide, we set out to research and develop a comprehensive set of Housing Policies for Belonging that could be implemented at the local level. In the past five years, Richmond has passed, implemented, and explored a number of innovative local policies to address the housing crisis, many of which are covered in our Existing Housing Policy section. This report seeks to build on this inspiring work. There may be gaps where we did not recognize or fully understand an issue, were not able to develop a solution, or could not address issues originating outside the scope of local policy action, so this is ultimately a work in progress and a living document that will only be as valuable as the collective work that goes into adding, refining, and trying out the ideas and strategies here.

The research here also benefits from the insight of numerous policy experts and Richmond residents who have reviewed and provided feedback to the report. The Haas Institute staff carried out quantitative data analysis, mapping, policy analysis, and legal research, and we take full responsibility for the report.

To navigate this online report, you can view individual sections and policies to the right. Brief introductions for each section are below.

The Need for Housing Policies for Belonging

What is clear from our analysis of data on housing in Richmond is that the squeeze on low-income renters, and Black people and Latinos in particular, has been building since the foreclosure crisis some 10 years ago. Foreclosures in Richmond spiked more than 600 percent between 2005 and 2008. One of the effects of the crisis was that many homes lost to foreclosures became rental properties, decreasing the percentage of Richmond households who own their home from 61 percent in 2005 to 49 percent in 2015.

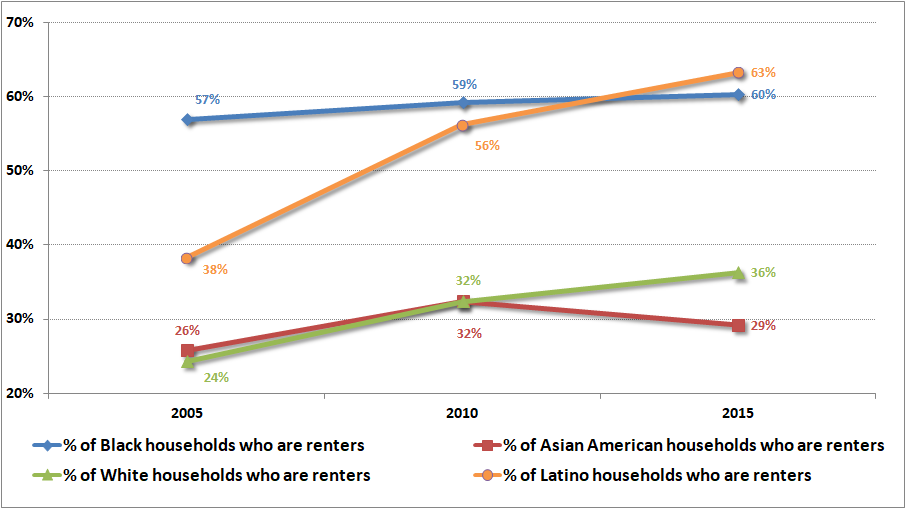

Substantial racial inequities exist in homeownership in the city: A majority of Black (60 percent) and Latino (63 percent) households are renters, compared to 36 percent of white households and 29 percent of Asian households. On the heels of the foreclosure crisis came a rise in speculative investment, with cash purchases making up about half of all home purchases in Richmond between 2009 and 2012. The asking rent in Richmond began to rise dramatically in 2013, going up 9 percent from 2013 to 2014, and 19 percent from 2014 to 2015, then only 4 percent through 2016, and not increasing through November 2017.

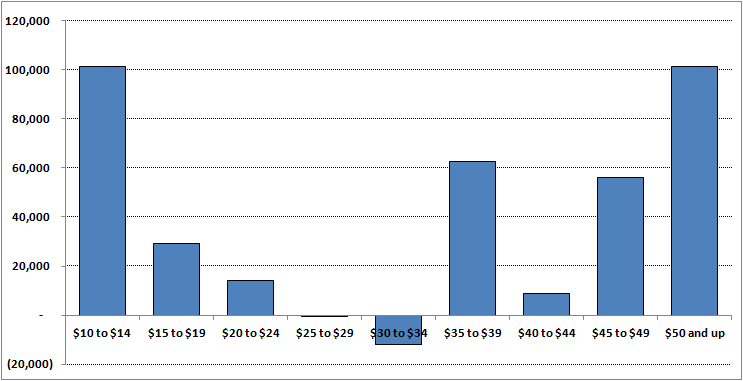

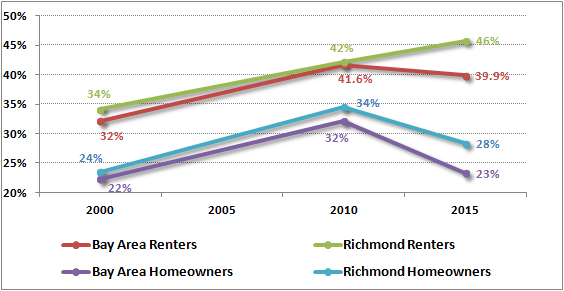

Meanwhile, most of the new jobs that opened in the East Bay were either very low wage or very high wage. Between 2009 and 2016, 100,000 new jobs were added in occupations that have a median wage of less than $15 per hour, and 100,000 jobs opened in occupations with median wages $50 per hour or higher. The unemployment rate in Richmond came down, but the median income didn’t go up. When housing costs go up, but incomes do not, affordability worsens. This has hit low-income renters the hardest: the percentage of Richmond renters who are overburdened by their housing costs increased from 34 percent in the year 2000, to 46 percent in 2015.

The production of housing that is affordable to low- and very low-income households has lagged far behind what is needed, worsening the shortage of affordable housing. From 2007 to 2014 Richmond permitted 31 percent of its target number of low- and very low-income units, and yet most cities in Contra Costa performed even worse, with jurisdictions in the county all together permitting only 22 percent of such units. In addition, most of the affordable units that were built recently were not located in neighborhoods with the resources and amenities to support healthy families. Looking at the affordable housing that was produced in Richmond using the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), all of the units were located in either low or lowest resource neighborhoods. While most of the neighborhoods in Richmond fall into either the moderate or low resource categories, none of the LIHTC affordable housing projects were built in the areas of Richmond with better amenities. This limits access to resources and opportunity for the low-income residents of these units, threatening to reinforce patterns of income and racial segregation.

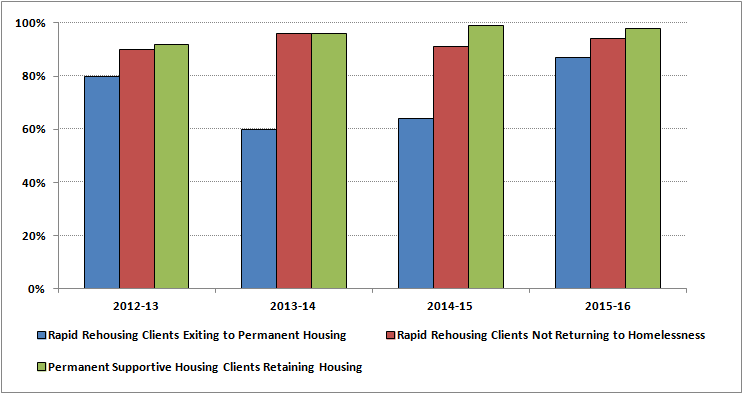

Rapid Rehousing and Supportive Housing programs serving homeless residents in the county over the last four years have had high success rates with the clients they are able to serve, but are not resourced enough to meet the need. Rapid Rehousing and Permanent Supportive Housing programs’ clients avoid homelessness over 90 percent of the time. However, these programs had only 218 beds in the county and were only able to serve about 1,000 people each last year, out of some 8,500 homeless people coming into contact with the county's Continuum of Care system. The chair of the county homeless council concluded that “the sluggish rate in the creation of affordable housing only means that homelessness, and the threat of homelessness, will continue.”

Current Housing Policy in Richmond

At the city level, Richmond is guided by a number of plans that are mandated by state and city laws, including the Housing Element of the General Plan, the Zoning Update Ordinance, the Regional Housing Needs Allocation, and Health in All Policies. The details of these plans are further concretized through local level policy and action. In the past five years, Richmond voters and City Council members passed a series of housing laws and initiatives that support a more equitable housing landscape. These efforts are frequently initiated by community organizations and have passed both by council approval, and at the ballot. While passage of such plans and policies is a critical step, the manner in which they are implemented is shaped by the priorities, resources, and capacity of city government, city residents, organizations, developers, and other actors. These actions ultimately dictate the scope and impact of existing policy on the community.

This section serves as a reference for community advocacy in identifying and prioritizing the elements of these documents that promote a comprehensive housing effort that advances belonging.

Housing Policies for Belonging: Protect, Produce, Preserve, and Build Power

The decisions that shape access to healthy, dignified homes and neighborhoods often are cloaked in complicated jargon and made in exclusive spaces. The structures and systems that result from these actions are frequently unseen and yet they deeply impact our lives. During the foreclosure crisis, for instance, many of us learned about securitization and subprime loans only after the damage had been done. Many decisions made about what kind of development can happen and where it can happen often move through administrative channels that are not easily accessible. Housing policy is most effective when it addresses these more structural forces, advancing structural inclusion. From a policy perspective, structural inclusion means that social, legal, and economic structures are designed to provide everyone access to resources essential for a full sense of belonging and wellbeing.

In analyzing and developing policy, the Haas Institute uses a framework we call targeted universalism. The term “universalism” refers to the idea that there should be a universal goal that will be achieved; for instance, making housing affordable for all residents. But for all to reach that universal goal, the policy must also be “targeted,” meaning it must include strategies specific to the particular barriers that some people face and others do not. For example, ensuring that the goal of affordable housing is achieved for seniors on a fixed income will require different strategies than reaching the goal for middle class homeowners. Richmond’s Health in All Policies ordinance reflects a targeted universalism framework: “Health equity entails focused societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities by equalizing the conditions for health for all groups, especially for those who have experienced socioeconomic disadvantage or historical injustices.” Often, the benefits of a targeted strategy also reach beyond the targeted population, such as how affordable housing for seniors creates stronger intergenerational communities and lessens medical costs.

The universal goals for housing policy must recognize that housing is about much more than just shelter. The home that you live in ties you to place, and this has a profound effect on your access to safe, healthy environments, economic opportunity, education, essential social networks, and other resources. These neighborhood environments can have substantial long-term economic and health effects. In the United States, owning a home is the primary way most working class families build wealth, which can protect them from a temporary loss of income or major expense like surgery or college tuition.

There is growing consensus that a comprehensive approach to housing issues must include strategies that cover “the four P’s”:

-

Protection: protecting tenants and socioeconomically disadvantaged residents

-

Production: developing appropriate additional housing

-

Preservation: preserving existing affordable housing

-

Power: strengthening the power of residents to ensure responsive and equitable housing decisions

Protection policies ensure that residents who are most impacted by housing issues like homelessness, discrimination, or unsafe housing have the rights and support they need. Existing Richmond housing policies that expand protection include rent control, just cause for eviction, and the fair chance housing ordinance. A new policy that advances protection and is discussed in the following section is the ordinance to prevent source of income discrimination. This policy would protect residents with Section 8 vouchers and other subsidized incomes from being discriminated against by landlords. Another policy that could expand protection is a reusable tenant screening report—a measure that provides tenants with an accurate and affordable report that they can reuse with multiple landlords. This saves tenants the money that each landlord typically collects for credit reports and background checks, and also protects tenants from having inappropriate and inaccurate information shared with landlords.

Housing policies that advance production lead to the development of additional housing units to meet the needs of existing residents, a growing population, and any mismatches in the affordability of housing produced. For instance, a housing linkage fee generates additional funds for affordable housing by charging a fee to new commercial, market-rate housing, or other development projects in the city. An affordable housing bond also expands production by using revenue from an increase in property taxes to fund the construction or preservation of affordable housing. A public lands policy can expand production by directing the city to lease or sell its surplus public land in ways that facilitate development of affordable housing and other community goods. Investments in transitional and supportive housing expand housing for residents who would often otherwise be homeless.

Preservation policies support the stability and quality of existing affordable and public housing. Preservation policies can fund needed rehabilitation of dilapidated affordable housing, and change ownership structures or contracts to ensure that affordable housing does not get converted to market-rate housing. The affordable housing bond can help preserve affordable housing by generating funds for rehabilitation of units that are in disrepair. The ordinance to prevent source of income discrimination can also advance preservation by making it easier for Section 8 voucher holders to secure housing on the private market. When voucher holders are discriminated against and cannot find a landlord to accept their voucher, they may lose the voucher, and unused vouchers often lead to the housing authority receiving less funding for affordable housing.

Housing policies that further the power of residents create new pathways and platforms for residents’ voices to be heard and shape housing decisions. For example, the creation of a Community-owned Development Enterprise (CDE) would put residents in the driver’s seat of designing and carrying out housing development projects. A housing speculation tax curbs and deters speculative investment, increasing the power of moderate-income home buyers and tenants in the housing market. The process itself can build the power of residents when they participate in developing, advocating for, and passing policy.

Summary Conclusion

Home is housing-animated— it is where the people, experiences, objects, and memories that make up our day-to-day lives are knotted together with broader relationships to people, places, and moments. Home is like scent, it evokes memory, accessing those parts of the brain that pull at emotions—good, bad, and intense.

Home is where housing and belonging come together. In this report we refer to “belonging” as not merely about having access to opportunities and resources, but being able to make demands upon political and cultural institutions. Belonging means being seen, listened to, and responded to at a structural level.

Housing can be described by any number of nouns and adjectives: shelter, temporary, investment, shortage, segregated, (un)affordable. But to describe housing without understanding belonging is to speak of statistics without people, place without human texture, buildings not homes. As Staying Power fellow DeAndre Evans asked, “How many of us aren’t statistics?”

In the San Francisco Bay Area, discussions on housing are endless—the shortage, the prices, the displacement, the inequality. In Richmond, a campaign to pass rent control and just cause for eviction laws in 2015 brought together Richmond renters, landlords, and local organizations into a powerful campaign to demand tenant protections from rising costs and unjust evictions. In demanding structural protection, they were asserting their belonging.

Their efforts were met with disdain from some elected officials in Richmond and rent control opponents. During one packed council meeting, a council member took the microphone and asked the audience to not be distracted by the stories of residents in the face of the facts that he had compiled. This framing of (his) facts vs. (their) testimony and lived experience was a false one; proponents had also done extensive research that showed statistical and factual justifications for rent control. At the root, his ask was a statement of dis-belonging—the experience of the marginalized is not how to direct the priorities of government. Such asks—and nearly $200,000 spent in opposition to the ballot vote on rent control—ultimately failed; rent control and just cause for eviction won at the ballot in 2016 with 65 percent of the vote and Richmond became the first city in California to pass a new rent control ordinance in over 30 years.

This was followed in late-2016 with another housing policy designed for formerly incarcerated people and advanced by a coalition of organizations such as the Safe Return Project and others. The Fair Chance Housing Ordinance prohibits public, low-income, and affordable housing providers from inquiring about prior convictions of an applicant—a “ban-the-box” for housing.

While only two tools in the broader efforts to make an equitable housing landscape in Richmond, these victories signal the importance and power of housing policies that advance belonging. While making explicit who does belong, they also support the stability of residents by offering some protection from the impacts of the housing crisis—a burden most heavily shouldered by Black, Latino, and low-income residents. Importantly, the victories also reflect the power of residents acting together to shape city policy that reflects their communities, an outcome that is contagious in its action-oriented hopefulness. “This body embody Richmond,” stated an organizer deeply involved in passing Fair Chance Housing. This is a statement of belonging—the experience and collective action of the historically excluded directing the priorities of government for the people.

Housing remains one of the defining factors of our lives. As author Matthew Desmond puts it bluntly, “Rent eats first.” Housing policies for belonging do not only have housing as their sole goal. Housing policies for belonging must address the ongoing impacts of racism and economic exclusion by inverting historical and contemporary place-based disenfranchisement; racial exclusion from homeownership is the single biggest factor in the racial wealth gap that today means the average white household wealth is seven times that of Black wealth and five times that of Latino wealth; education quality is intimately tied to where people live, a factor shaped by housing policy, zoning, and tax code; housing access and zoning have resulted in disproportionate exposure to environmental pollution for low-income people of color; and racial residential segregation can increase toxic stress with long-term negative health outcomes. One of the end results of these inequities is that Black residents in Richmond have been displaced from their historic neighborhoods, whether through the rising costs of housing, in pursuit of better education, or out of safety concerns. In Richmond, the Black population has fallen from 36,600 in the year 2000 to 23,500 in the year 2015 (a 36 percent decrease).

Stable, affordable, quality housing and the ability to move if one wants to—not to be driven out by violence, rising prices, failing schools or exclusionary policies—provide undeniable foundations for the thriving of Richmond residents and the city as a whole. Policies of belonging mean that structurally excluded residents can benefit from the improvements of place and development that are happening, and will continue to happen, in Richmond over the long-term.

By supporting Richmond as home, housing policies for belonging are not an end, but a framework for expanding the health, wealth, and power of Richmond residents.

Preface

By Sasha Graham-Croner, Staying Power Fellow, 2017

I am truly grateful to be part of the Staying Power Fellowship, a six-month participatory action research and art fellowship about housing and belonging in Richmond. It allowed me to speak to the truths of my community. My family and friends have been affected by the issues set forth in this report. To be able to participate in a collaborative manner with others who share the vision of a strong, unified Richmond has brought hope to those assumed forgotten. The opportunity for my fellows and I to work alongside our community to ensure their future through this work is something I will never forget. I will never give up on this place I call home. The mural I helped to envision and create is now for all to see, I am now known as a warrior in my community and I intend to live up to it for as long as I am alive.

According to Abraham Maslow’s "Hierarchy of Needs," the first and second tiers of human need include meeting our physiological needs and basic safety: housing is necessary for both. By providing this foundation, housing creates the opportunity for operating at our full potential.

The need for quality housing for in Richmond has reached a critical point and must be addressed with a multidimensional set of lenses. When we look at housing through different lenses—through stories, histories, policies, statistics, economics, arts—the theme of belonging emerges as central to addressing housing needs. Belonging within a city is not about being born there. It is not even about owning a home there. Belonging represents the communal spaces that are genuinely inclusive and supportive to all.

Many of the issues in Richmond seem to be tied to a disconnection between housing and belonging among its leaders. As residents, there is a need to educate ourselves on the historical, social, economic, and political contexts that have brought the long growing problem of housing to its current critical point. During the Staying Power fellowship, we looked at overlapping factors to design methods of analyzing the conditions and needs of marginalized and oppressed populations in Richmond. Many Black families in Richmond have endured rent increases without limits and eviction without just cause. Many immigrants, particularly undocumented Latinx families in Richmond have endured horrible living conditions because of their status. And for many formerly incarcerated individuals, homelessness is the name of the game. These atrocious realities have left individuals and families with no home and, just as importantly, hopeless and with no sense of belonging.

Research that employs various methods can be very useful here. By engaging directly through oral histories and interviews with populations who have been the most affected, and integrating those with data and statistics, we can create the type of real-world analysis needed to develop and implement real, sustainable solutions.

Ongoing activism around housing issues in Richmond has aided in the passing of laws to help address and rescue many families from displacement and despair. However, laws are ineffective without accountability. Many families have still suffered displacement and harassment from landlords that refuse to acknowledge the new ordinances. Historically excluded from benefits of the legal system, how could a mother know or believe she could challenge her landlord when she was disconnected from a decision made in the halls of the city government? In Richmond it will take accountability from our leaders to step up and give priority to the housing crisis. “Affordable” housing excludes many people who are “low income” or have no income—delving into terminology and the details of development shows the lack of concern for those who have no names behind politically closed doors.

We cannot rest on these successes. We must call for the construction and renovation of even more low-income housing within the city. Laws need to be fully enforced by the powers of the city. In my own experience, in 2017 I was pressured to leave the home I was renting. I was not given a 30-day notice, nor any explanation, just a threat of violence if I did not vacate within a couple days. When the person tried to attack my family and me, the police were called; when they arrived, their only advice was for me to vacate for my safety. Even with the Just Cause for Eviction ordinance, the police suggested that my rights as a renter did not matter and that the only way to keep myself from violence was to leave with my child and be homeless. I did just that. I left, but with nowhere to go. This trial motivated me to keep going with the Staying Power Fellowship and to make sure the mural project I was leading lifted up the rights of those whose voices are not heard by some city leaders or its protectors. To do this requires a sense of belonging that emanates from those who live here and serve here.

The need for community—real community—is an integral part in solving the housing crisis. We must have knowledge and respect for those who we call neighbors, constituents, and leaders. This respect will lead us to think first of stabilizing the homes and lives of those who have been neglected and who deserve to stay in Richmond.

Leaving your home, the place and community where you belong, should be a choice you have made, not an inevitable result of displacement for capitalistic interests.

This is home (poem)

By DeAndre Evans

This is where rodents and roaches are like family

Cause we share da same meals

Top Ramen Cereal Kool Aid

It’s no family complaints everything enjoyed that we refrigerate and put in cabinets

Bathroom sink replace our bathtub so I can wash as well as da shame

We feel 30 below air from cracked windows no heat for when Richmond wind blows

No ac to cool down the weather dat make us sweat

Neglect da only thing we get

Fungus disintegrate da walls intoxicate our breath

No one is responsive, feels like I’m talking to myself

When help is asked to restore something simple as a lock on a gate

So I can feel safe

Microwaves being used as our stove and oven

No fried chicken or fries or anything dat needs to be cooked

We relied on heated up food

Had to learn to go nights without lights and warm showers

Going to school with Goosebumps from da temperature of da water

Tired of these offices blaming me for conditions

Like these conditions weren’t demons living in dis basement of satan

It’s a list people who wait and wait to be rejected to stay here

But when you’re Americas darker skin babies

You’re treated less than a stepchild or even less than a pet

This is home

Where I’m too young to worry but not too young to care

Three kids wasn't enough for us to be late for rent

Put us on the street nine deep sleep in the U-Haul truck

Giving is a foreign word to people better yet a foreign act

It’s easy to be pissed because of living in da gutters

This where we have to be protected by those who protect and serve cause they

serving yea they serving us wit us tasers clubs and bullets

Wit da result of painful scars

Men are quick to raise guns and fists but not nearly as quick to raise our kids

Single mothers are seen on corners more than street signs

Feels like you're saying goodbye to people before hello and you let go

More funerals than birthday parties while prisons become like our graduation

Being pushed and moving to places dat have so called better situations

We ain't knowing only going cause where we at we ain't owning

This is home

Where we don't always have what we want

but always what we need depending on our faith

Some of us believe, worship a higher power over money

We genuinely love one another will give

Some men step to be fathers even to kids who are not theirs

One day we will hear more of sis and bro not just nigga or hoes

Shelter will be provided and no one will be denied it

That five-year-old boy will not be forced to the street

Where the community will see the sunshine

It won’t be clouded by the smoke of guns weed and nicotine

This is tomorrow

I will act on making it today

Introduction

What does it mean to really belong in Richmond? How do our homes shape how we think of who belongs? What actions are needed to achieve a city where everyone belongs? The stories, research, data, poems, images, and policy ideas in this report center on these questions. As we write in the conclusion, “To describe housing without understanding belonging is to speak of statistics without people, place without human texture, buildings not homes.”

Art brings us closer to understanding what is truly at stake. Ciera-Jevae Gordon writes in her original poem found later in the report that:

...having a home is essential

And I ain’t got one

It’s a human right

but do they even think I’m human?

Like this poem, much of the research and development of this report was done by the Staying Power Fellows, a group of Richmond residents impacted by the housing crisis who conducted interviews, analyzed data, and explored their own life experiences. For example, fellow Noe Gudino researched the Source of Income Discrimination policy, which led to the concept of a Reusable Tenant Screening Report (see Housing Policies for Belonging). The fellows wrote and performed poetry, developed a large public mural, drafted policies—and all of this work is being shared with the community.

The research in this report also comes from the insights and ongoing work of many Richmond-based organizations and other residents. On June 3, 2017, eight organizations co-sponsored a Citywide Housing Symposium, where over 100 participants discussed housing issues in Richmond and policies to address them.1 Public spaces for community leaders have also been a source and a sounding board for the research, including the GRIP Social Justice Forum and the Richmond Progressive Alliance Housing Action Team.

A rigorous research process that begins with supporting people most impacted by the issues to design and carry out their own analysis, and connects with community-based organizations that organize residents to collectively advocate for themselves, makes for more responsive housing decisions and begins to reverse the power imbalances that perpetuate homelessness, lack of affordability, and other issues. Responsiveness to everyone’s well-being must be at the heart of change, as fellow DeAndre Evans writes in one of his poems:

...No one is responsive,

feels like I’m talking to myself

When help is asked to restore something simple

as a lock on a gate

So I can feel safe.

Recognizing that there is no single solution to the housing crisis affecting not only Richmond but the whole nation, we set out to research and develop a comprehensive set of solutions. In the past five years, Richmond has passed and explored a number of innovative local housing policies. This report seeks to build on that inspiring work. There may be gaps where we did not fully explain an issue, were not able to develop a solution, or could not address issues originating outside the scope of local policy action; this is ultimately a work in progress and a living document that will only be as valuable as the shared work that goes into adding, refining, and trying out the ideas and strategies here.

The research here benefits from the insight of numerous policy experts and Richmond residents who have reviewed and provided feedback.2

Staff from the Haas Institute at UC Berkeley carried out quantitative data analysis, mapping, policy analysis, and legal research.

About the Staying Power Project

Staying Power is an arts, policy, and participatory action research fellowship coordinated by ACCE, the Haas Institute, RYSE, and the Safe Return Project. The 2017 Fellows were: William Edwards, Safe Return Project; DeAndre Evans, RYSE; Ciera-Jevae Gordon, RYSE; Sasha Graham-Croner, ACCE; Noe Gudino, ACCE; and Satina Shaw, Safe Return Project.

The six-month fellowship began with the fellows sharing personal narratives and then building context around these stories through analyzing the structures and systems that impact their lives. The fellows met weekly to engage in a wide variety of activities including: creative work such as root cause and personal history mapping, photo-stories, tableaus, and collective writing exercises; readings such as the Richmond Marketing Research Report commissioned by the mayor’s office and Richmond Main Street Initiative, and academic or journalistic pieces on housing issues in Richmond; skills trainings including project planning, video training, and interview question development; and project work and group feedback. The group used these activities to identify overlaps, disconnects, core themes, and needs in their own communities' narratives and experiences. This process informed the design and implementation of arts and culture projects, which then informed fellows’ ongoing relationship to these issues.

Highlights of the Staying Power Fellowship include:

• Over six months, held over 35 interviews and informal conversations with current and former Richmond residents about the topics of housing and belonging to inform the different project outcomes and directions of the group.

• Attended community meeting on the closing of the Las Deltas Housing site in North Richmond.

• Designed and implemented interactive activities for the lobby of “Richmond Renaissance,” a play written by Staying Power fellow DeAndre Evans and produced by RYSE.

• Performed a collective poem at the Richmond Citywide Housing Symposium, the Richmond City Council, and a Section 8 homeownership workshop by Richmond Neighborhood Housing Services.

• Hosted two 90-minute workshops on designing the “know-your-rights” mural with Safe Return Project and ACCE. Sixteen attendees gave feedback and input into the mural.

• At Manor Housing (now Monterey Pines), fellow Ciera-Jevae Gordon facilitated eight writing workshops for Richmond children aged five to ten about housing and belonging.

• Fellow Ciera-Jevae Gordon created a book of 10 poems based on interviews with Richmond residents that included images and interviewers notes.

• Fellow Sasha Graham-Croner co-led the design and creation of a large-scale (60’x12’) “know-your-rights” mural about recent housing laws passed in Richmond, including two community paint days.

• Fellow Noe Gudino co-wrote a draft “source of income” ordinance and began exploring possibilities for a “reusable screening report” ordinance.

The Staying Power project was directed by Eli Moore of the Haas Institute and coordinated by Evan Bissell, artist and researcher. For more information, see belonging.berkeley.edu/stayingpower.

Foundations of a Housing Crisis

In Richmond, home appreciation is greater in neighborhoods that were previously segregated white, which were less densely zoned and have fewer exposures to environmental toxins.3

Prior to the foreclosure crisis, Black and Latino homebuyers were over three times more likely to receive risky loans than white borrowers, even with similar credit scores and income.4

Between 2000 and 2013, the Bay Area gained 94,408 low-income households and simultaneously lost 106,000 naturally-occurring affordable housing units.5

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Richmond Realtors’ Association refused the entry of Black realtors.6

Black and Latino residents, who make up the majority of Richmond residents, have the least access to high opportunity jobs in the region.7

In 2017, 63 percent of Richmond’s General Fund budget was allocated to public safety, the largest single category.8

Until a protest campaign in 1959, school district boundaries required Black high school students to travel out of their neighborhood to a Black school. Elementary schools were already segregated because the neighborhoods they were placed in were segregated.9

Black residents who challenged housing segregation met violence and little protection from police. When the Gary family moved to a white subdivision called Rollingwood in 1952, they were met by the local KKK and white mobs. An interracial local organizing campaign came together to protect the family.10

Black residents began to move to southside Richmond through blockbusting—where realtors stoked the racial fears of white homeowners by convincing them the block was “changing,” getting them to sell their homes quickly, and then turning around the homes and selling them at higher prices to Black people with fewer housing options.11

In 1953, Ford moved its plant to Milpitas and white workers followed, able to purchase homes in the surrounding area using federal subsidies and loan programs. Black union workers, like white workers, had guaranteed job rights, but could not buy homes in these new subdivisions.12

Between 2009 and 2013, the Bay Area added the vast majority of its jobs in high wage (above $50/hr) and low wage (below $15/hr) positions.13

As unincorporated county land, North Richmond, and its majority Black residents had limited direct political representation.14

During WWII, around 80 percent of the Black community lived in temporary war housing that was then demolished in 1953 through “Urban Renewal” programs. Restrictive covenants forced them into segregated and underresourced neighborhoods, into predatory housing schemes (blockbusting) or directly into violent attacks from white residents.15

Due to racially restrictive covenants as early as 1909 (and some as late as 1963), it was extremely difficult for Black residents to purchase homes outside of North Richmond. These lots were zoned at 25 ft. wide and banks would not lend there, forcing people to construct homes from makeshift materials. By contrast, exclusively white Atchison Village, constructed with federal funds in 1941, had 20 ft. distances between homes.16

Even at the height of the war, at Standard Oil (now Chevron), only 5 percent of employees were Black.17

Despite employment in the Kaiser shipyards and the Ford assembly plants, Black workers were excluded from many unions in Richmond and were often given low level positions.18

Police harassment of the Black community in North Richmond was common enough that in 1954 both the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Conference of Christians and Jews operated defense programs.19

During the war, Black people stopped by the police who could not show proof of employment were subject to arrest.20

By the Numbers: Housing Needs

What is clear from our analysis of data on housing in Richmond is that the squeeze on low-income renters, and Black and Latino residents in particular, has been building since the foreclosure crisis some 10 years ago. Foreclosures in Richmond spiked more than 600 percent between 2005 and 2008.21 One of the effects of the crisis was that many homes lost to foreclosures became rental properties, decreasing the percentage of Richmond households who own their home from 61 percent in 2005 to 49 percent in 2015.

Substantial racial inequities exist in homeownership in the city: A majority of Black (60 percent) and Latino (63 percent) households are renters, compared to 36 percent of white households and 29 percent of Asian households.22 On the heels of the foreclosure crisis came a rise in speculative investment, with cash purchases making up about half of all home purchases in Richmond between 2009 and 2012.23 The asking rent in Richmond began to rise dramatically in 2013, going up 9 percent from 2013 to 2014, and 19 percent from 2014 to 2015, then only 4 percent through 2016, and not increasing through November 2017.24

Meanwhile, most of the new jobs that opened in the East Bay were either very low wage or very high wage. Between 2009 and 2016, 100,000 new jobs were added in occupations that have a median wage of less than $15 per hour, and 100,000 jobs opened in occupations with median wages $50 per hour or higher.25 The unemployment rate in Richmond came down, but the median income didn’t go up. When housing costs go up, but incomes do not, affordability worsens. This has hit low-income renters the hardest: the percentage of Richmond renters who are overburdened by their housing costs increased from 34 percent in the year 2000, to 46 percent in 2015.26

The production of housing that is affordable to low- and very low-income households has lagged far behind what is needed, worsening the shortage of affordable housing. From 2007 to 2014 Richmond permitted 31 percent of its target number of low- and very low-income units, and yet most cities in Contra Costa performed even worse, with jurisdictions in the county all together permitting only 22 percent of such units. In addition, most of the affordable units that were built recently were not located in neighborhoods with the resources and amenities to support healthy families. Looking at the affordable housing that was produced in Richmond using the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), all of the units were located in either low or lowest resource neighborhoods.27 While most of the neighborhoods in Richmond fall into either the moderate or low resource categories, none of the LIHTC affordable housing projects were built in the areas of Richmond with better amenities.28 This limits access to resources and opportunity for the low-income residents of these units, threatening to reinforce patterns of income and racial segregation.

Rapid Rehousing and Supportive Housing programs serving homeless residents in the county over the last four years have had high success rates with the clients they are able to serve, but are not resourced enough to meet the need. Rapid Rehousing and Permanent Supportive Housing programs’ clients avoid homelessness over 90 percent of the time. However, these programs had only 218 beds in the county and were only able to serve about 1,000 people each last year, out of some 8,500 homeless people coming into contact with the county’s Continuum of Care system. The chair of the county homeless council concluded that “the sluggish rate in the creation of affordable housing only means that homelessness, and the threat of homelessness, will continue."29

Homeownership

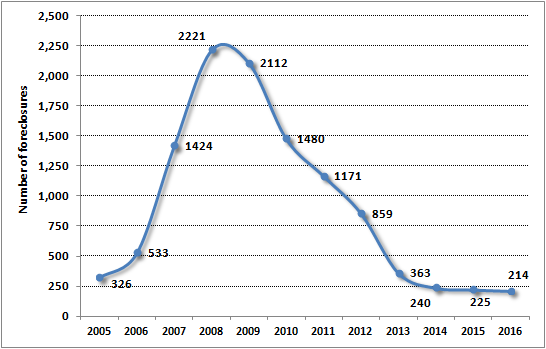

The extreme number of foreclosures has decreased, but the effects of the foreclosure crisis continue to impact Richmond

Chart 1: Number of Foreclosures in Richmond, 2005-2016

During the Great Recession, from 2007 to 2012, 6,300 residential properties in Richmond went into foreclosure.30 The number of foreclosures peaked in 2008 and has decreased each year to levels similar to 2005, before the recession. However, as late as the end of 2013, when the number of foreclosures that year had dropped to pre-recession levels, more than one in four Richmond homeowners were still underwater on their mortgages (meaning they owed more on their mortgage than the fair market value of the property) and the city estimated that 30 percent of homes in Richmond were financed with subprime loans.31 Overall, after the impact of the foreclosure crisis, the percentage of Richmond households who own their homes dropped from 61 percent in 2005 to 49 percent in 2015.32 The subprime lending that drove the foreclosure crisis was disproportionately targeted at Black and Latino homeowners, even when comparing borrowers within the same credit score range.33 Despite the rapidly climbing housing values over the last few years, 4.4 percent of the residential properties in Richmond have underwater mortgages.34

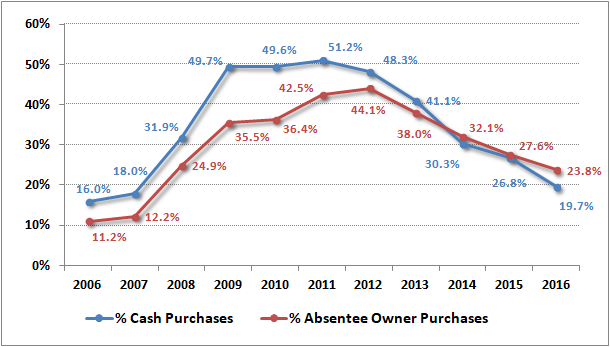

A spike in cash and absentee owner purchases followed the foreclosure crisis in Richmond

Chart 2: Home Purchases with Cash and Absentee Owners in Richmond, 2006-2016

From mid-2009 to mid-2012, a majority of homes sold in Richmond were purchased with cash. The percentage of absentee owner purchases tripled between 2008 and 2012. The percentage of homes purchased by absentee owners or with all cash has come down to around one in five purchases of Richmond homes in 2016, which remains higher than pre-recession levels. These trends point towards speculative investment in the housing market, otherwise known as an economic investment in housing based on the speculation that housing value in a specific area will increase rapidly for a profitable resale or provides the ability to charge increased rents at profit.35

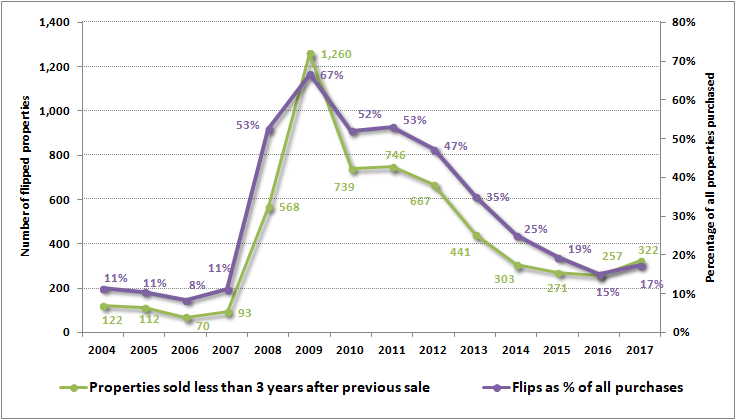

House flipping in Richmond spiked after the foreclosure crisis and remains higher than pre-crisis

Chart 3: Residential Richmond Properties Sold Less than Three Years after Previous Sale, 2004-2017

House flipping is the practice of buying a property and quickly reselling it for a profit and is a form of speculative investment. Between 2000 and 2007, owners sold 589 Richmond properties within three years of purchasing them. In contrast, between 2008 and 2017, there were 3,593 properties resold within three years. The largest increase in house flipping occurred in the early years of the Great Recession. In 2007 there were only 93 Richmond properties sold that had been bought within the previous three years. In 2008, this number rose by over 600 percent to 568, then more than doubled again the next year in 2009. After 2009, flipping decreased, and over the last four years (2013-2017) has been around 300 properties flipped per year, which is three times as high as pre-crisis levels. A 2016 analysis by RealtyTrac found that housing in the Richmond zip code 94801, which includes Central Richmond, Point Richmond, and unicorporated North Richmond, had the highest return on investment of any zip code in the Bay Area.

Renters

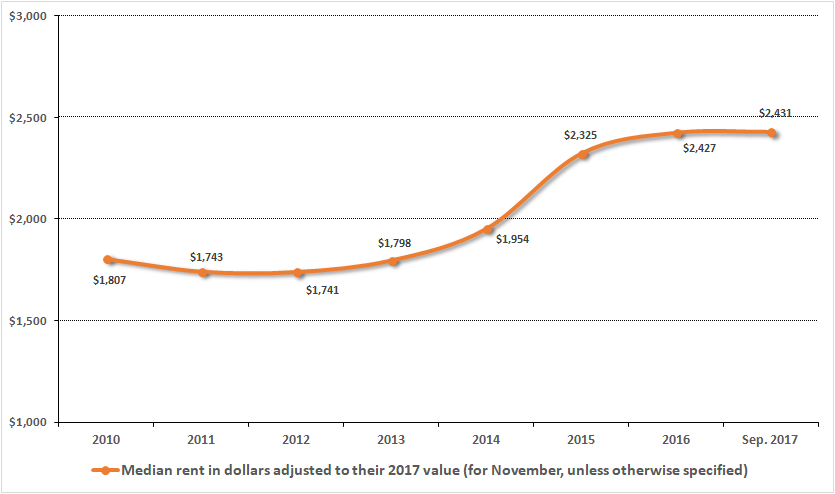

Rent has risen by over a third in Richmond over the last eight years

Chart 4: Richmond Media Rent for All Housing Types in Richmond, 2010-2017

As with the larger Bay Area, Richmond experienced an increase in median rents between 2010 and 2017. This chart displays the median asking rents between November 2010 and September 2017. During this entire time period, rents increased by 35 percent, with the largest single jump occurring between 2014 and 2015 (19 percent during a 12-month period).

Black and Latino households in Richmond represent a disproportionate percentage of renters

Chart 5: Percentage of Renters by Race in Richmond, 2005-2015

Across racial groups, a higher percentage of Richmond households are renters in 2017 compared to 2005. A majority of Black (60 percent) and Latino (63 percent) households are renters, while 36 percent of white, and 29 percent of Asian households are renters. The percentage of Latino households comprised of renters rose from 38 percent in 2005 to 63 percent in 2015, now the highest in the city. The percentage of Black households renting was twice as high as the percentage of white households renting in 2005, and this gap decreased slightly by 2015.36

More people are working but wages of new jobs reflect extreme inequality

Chart 6: Change in Number of Jobs by Hourly Wage Category, Oakland-Hayward-Berkeley MSA, 2009-2017

The current unemployment rate in Richmond is low (under 5 percent for the population overall)37 but the median household income in Richmond ($55,000) has barely risen since 2009.38 Racial disparities in employment also persist, with the 2015 unemployment rate at 5.5 percent for white residents, 8 percent for Asians, 10 percent for Latinos, and 18 percent for Black residents in Richmond.39 The wages of the new jobs reflect extreme inequalities—between 2009 and 2017, most of the new jobs that opened in the East Bay were either very low wage or very high wage jobs. About 100,000 new jobs were added in occupations that have a median wage of less than $15 per hour, and around 100,000 jobs opened in occupations with median wages $50 per hour or higher.40 While Richmond city council voted in 2017 to raise the minimum wage, the wage needed for a single adult working full-time with an infant child to be self sufficient in Contra Costa County is $28 per hour.41 About 145,000 (63 percent) of the new jobs in the East Bay since 2009 have median incomes paying less than this level of self sufficiency. The income inequality generated by this type of economic growth contributes to the housing crisis by creating a large difference in what people can spend on housing, thereby creating unbalanced competition for available housing.

Housing is less affordable in Richmond relative to incomes, and renters are the most burdened by unaffordable housing costs

Chart 7: Overburdened Renters and Homeowners in Richmond and the Bay Area, 2000-2015

Housing affordability refers to the relationship between people’s income and housing costs. Most housing agencies consider a household over-burdened with housing costs if the household pays more than 30 percent of their income towards housing. Despite being one of the most affordable cities in the Bay Area, the percentage of Richmond renters who are over-burdened by their housing costs increased from 34 percent in the year 2000, to 46 percent in 2015.42 In the 2016 Richmond city survey, only 39 percent of residents said they were “not experiencing housing cost stress.” The national survey company conducting the survey compared this response to other communities where a similar question was asked and found that Richmond had the lowest positive rating regarding housing cost stress of the 240 communities surveyed.43 In Richmond and throughout the rest of the Bay Area, a higher percentage of renter households are over-burdened by their housing costs when compared to homeowners.

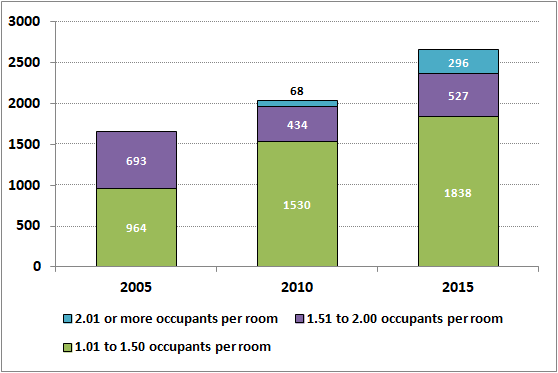

Tenants are responding to unaffordable rents by crowding more people into less housing

Chart 8: Crowding in Renter-Occupied Homes in Richmond, 2005-2015

Among homeowners in Richmond, over-crowding decreased between 2005 and 2015, but among renters, over-crowding has increased substantially. The number of over-crowded renter households with one to 1.5 people per room nearly doubled from 2005 to 2015, increasing from 960 to 1,840.44 Compared to other cities in the Bay Area, Richmond had one of the highest rates of over-crowded households in the Bay Area in 2013, according to ABAG.45 Crowding more people into less housing is often a response to unaffordable housing. Crowding more than one person per room is associated with worsened respiratory conditions, stomach cancer, psychiatric symptoms, mental illness, and other worsened health conditions. Crowding at the higher rate of 1.5 people per room can lead to worsened child mortality, reading and mathematical testing, and increased accidents.46

Affordable Housing Production

The county and region are far behind in producing enough affordable housing for population growth

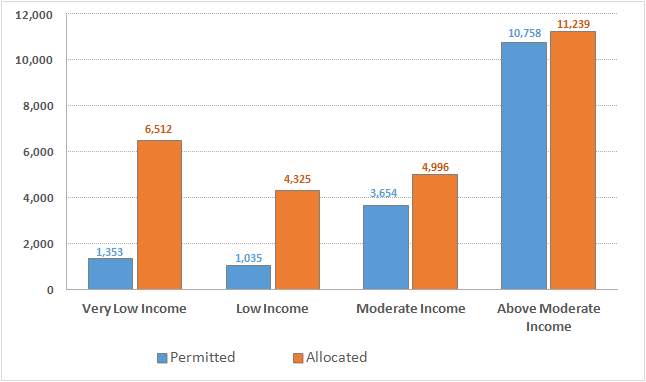

Chart 9: Contra Costa County Housing Units Permitted Relative to Units Allocated (by Income Category), 2007-2014

Housing pressures at county and regional levels impact the mobility of low-income Richmond households and increase affordable housing demand. The region has almost reached its goals for building new higher-income housing, but has fallen far short in developing housing affordable to lower-income households. Between 2007 and 2014, Contra Costa Co. developed 96 percent of the housing units needed for above moderate-income households and 73 percent for moderate-income households, but only 24 percent for low-income households and 21 percent of what was needed for very low-income.47 While Chart 9 displays a timespan that coincided with a construction downturn during the Great Recession, the ability to finance affordable housing in the region was further exacerbated by an overall decrease in funding from state and federal sources during the same time period.48 The trends in Contra Costa Co. mirror those of the entire Bay Area. Contra Costa as a whole permitted more moderate-income housing than the rest of the region.49

Richmond is developing more affordable housing than many other cities in the county, but not nearly enough to meet need

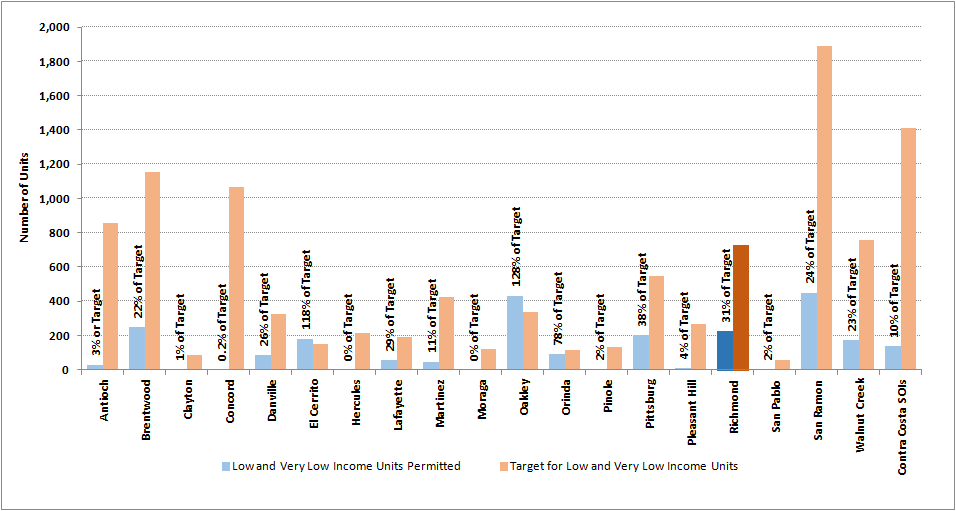

Chart 10: Contra Costa Cities' Progress Towards Affordable Housing Goals, 2007-2014

Every seven years, the regional planning agency in the Bay Area, known as the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), sets affordable housing development goals for each city in the region based on the region’s population growth and housing needs, among other factors. Each city is given a goal for the number of units it should build in the seven-year period at very low-, low-, moderate-, and above moderate-income levels.50 From 2007 to 2014 Richmond only permitted 31 percent (227 housing units) of its target number of very low- and low-income units, which, however, was the fourth highest out of 19 incorporated cities in Contra Costa County in number of units produced and percentage of allocation achieved at those income levels. As a whole, cities in Contra Costa only permitted 22 percent of the very low- and low-income units that were needed in Contra Costa County between 2007 and 2014.

All Low- and Very Low-Income Housing Units Built in Richmond Between 2003-2015 were Built in Low or Lowest Resource Neighborhoods

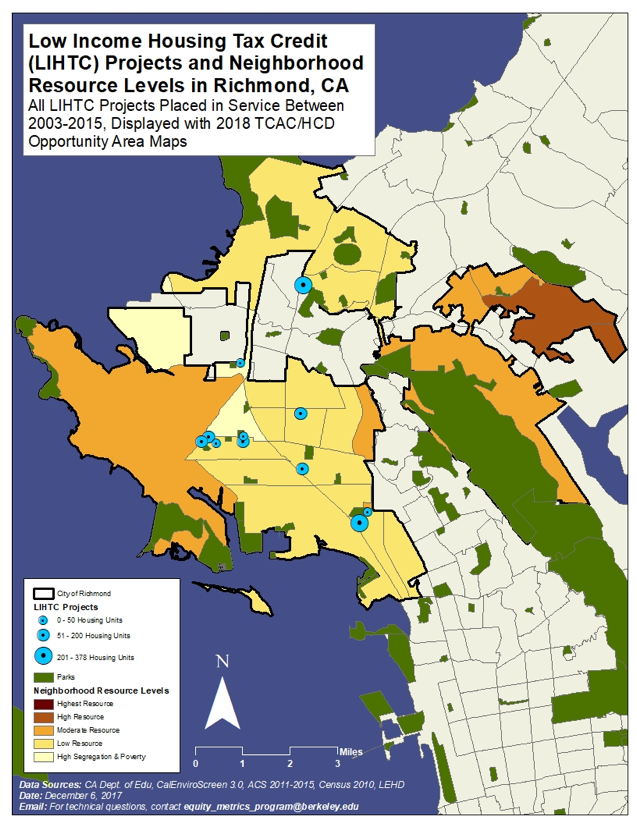

Map 1: Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) Projects and Neighborhood Resource Levels in Richmond

Map 1 shows where many of the housing units that counted towards Richmond’s lower-income housing goals have been built. These projects were all financed through the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, a federal program that is administered by each state and is the largest source of funding for affordable housing in California. The 13 projects represented in the map were placed in service between 2003 and 2015 and account for over 1,500 total units, 97 percent of which were affordable to low-income households.51 Note that most of these units were concentrated in central Richmond, with other projects scattered mostly throughout central and southern Richmond, and that all of the units were located in either Low or Lowest Resource neighborhoods.52 This is part of a broader pattern in the Bay Area; nearly two-thirds of LIHTC projects (64.9 percent) in the nine-county area were sited in Moderate, Low, and Very Low Opportunity neighborhoods during the years for which data was available (1987-2014).53 While most of the neighborhoods in Richmond fall into either the Moderate or Low Resource categories, all of the projects were built in the low and lowest resource areas of Richmond, with none in Point Richmond or Eastern Richmond.

Chronic underfunding sparks transition in the model for providing permanently affordable housing

Nationally, public funding for permanently affordable housing has been cut so dramatically that public housing faces a $26 billion backlog of needed repairs.54 In order to address this lack of funding, HUD developed the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program, through which participating housing authorities (like the Richmond Housing Authority) can convert public housing to private ownership, while ensuring long-term affordability through a contract with affordability restrictions that can be renewed each time they expire.55 The Richmond Housing Authority (RHA) board, which is made up of the members of the City Council, has approved RAD conversion of four of the public housing developments owned by the RHA.56 Management of two of those developments, Friendship Manor and Triangle Court, has already been turned over to the John Stewart Company.57 Temporary tenant relocation at both of these properties took place at the same time as renovations. The other two RHA-owned public housing developments, Nevin Plaza and Nystrom Village, have received RAD funding and are scheduled for renovation in 2017. The $160 million Nystrom Village revitalization project will draw from both public and private funding sources.58 The Richmond Housing Authority has not finalized a relocation plan for neither Nevin Plaza nor Nystrom Village.59 Another challenge facing the RHA's model of providing affordable housing is the difficulty placing Section 8 voucher holders, who must find private landlords willing to accept their subsidized rent payments. Around 300 Section 8 vouchers are going unused, leaving unfulfilled the needs of those 300 extremely low-income households and jeopardizing the future funding of the RHA.60 Mismanagement at the Richmond Housing Authority has drawn criticism and threats of sanctions from HUD.61

Homelessness

Homelessness is persistent but may be coming down in Richmond

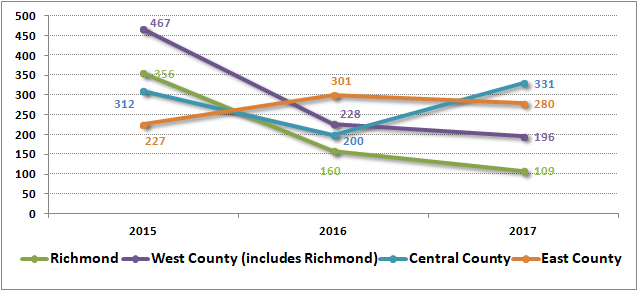

Chart 11: Point in Time Count of Homeless Population in Richmond and Regions of Contra Cosa County, 2015-2017

When the most recent annual count asked homeless people across Contra Costa what city they were in when they lost their permanent housing, 198 were from Richmond out of a total 807 in the county.62 No other city in the county had more homeless people who formerly called it home. Data on homelessness has limited reliability due to the lack of comprehensive surveys, but in a one-night survey, the surveyors documented 109 people experiencing homelessness in Richmond, including 57 percent who were sleeping outside.

This annual survey has found the number of people homeless in Richmond decreasing in each of the last three years, from 356 in 2015, to 160 in 2016, to 109 in 2017.63 The Contra Costa survey found “a significant increase in central county and decrease in west county. Some of these trends may reflect a shift in the homeless population and/or the effectiveness of efforts adopted at the local level to address homelessness.” A recent estimate from the Richmond mayor and the police department put the Richmond homeless figure nearly eight times higher, at 800 individuals and 76 encampments.64 A recent investigation by a Contra Costa Grand Jury interviewed homeless service providers, who thought the number of homeless people at 20 to 50 percent higher than what the one-night survey found.65

Children, LGBT youth, seniors, formerly incarcerated, and people with mental health conditions are disproportionately affected by homelessness

Some 160 children were encountered in homeless families during the county’s annual count, as well as 78 transition age youth (18-24 years old).66 LGBT youth experience homelessness at higher rates than non-LGBT youth for a range of reasons, related to sexuality and gender-based discrimination.67

The county also reports that “the County’s homeless population had a higher proportion of seniors and individuals with chronic or mental health conditions” than it did five years ago.68

Self-reports by the 1,400 homeless individuals served by Rubicon’s West County Economic Empowerment Services between 2012 and 2016 show that 43 percent had been convicted of a crime and 39 percent had served time in prison or jail. County data shows similarly high rates of homeless who were previously incarcerated.69

Supportive housing programs are effective, but don't have necessary resources to place enough people in permanently affordable housing

Chart 12: Effective Rate of Rapid Rehousing and Supportive Housing Programs in Contra Costa Country, 2012-2016

The Rapid Re-housing and Supportive Housing programs in Contra Costa County have high rates of success in helping clients not return to homelessness, but are only able to serve a small portion of the people who are homeless. On average, Rapid Rehousing programs in the county over the last four years have placed clients in permanent housing 73 percent of the time, and helped them avoid homelessness 93 percent of the time. Permanent Supportive Housing programs have had an even higher success rate, with an average of 96 percent of clients retaining their housing.70 However, those two programs had only 218 beds and served about 1,000 people each last year, out of some 8,500 homeless people coming into contact with the county’s Continuum of Care system. The system as a whole has the most difficulty placing people in permanent housing. The chair of the county homeless council concluded that “the sluggish rate in the creation of affordable housing only means that homelessness, and the threat of homelessness, will continue.”71 GRIP, interviewed as one of the only transitional housing programs in Richmond, also reports that it has been highly difficult to move the families in their programs out into permanent housing.

Have you noticed any change lately? (poem)

By Ciera-Jevae Gordon

Have you noticed any change lately?

Granny left,

Tried her luck elsewhere

then came back.

I suppose she learned

leaving doesn’t solve all of your problems.

Or maybe your problems stretch out farther

than your price range will allow you to travel

We teeter between living and waiting to die.

Because we can’t breathe,

it’s hard to see,

hard to feed myself,

let alone any kids that come from this womb

Another home plagued, and I have little control

Living in poverty is bad for your health

Most of us don’t make it past 50

And even that is a luxury where I come from

A whole community losing

wealth and equity

We fill our bellies with emptiness, no hope

Cause we poor and we broke

You can tell by my lack of smile

That I’ve been dead for awhile

But my bones owe somebody something

So we just keep on moving

Someone once told me that my worth

didn’t equate to materials or possessions

But all I could reply is

Prove it.

Because having a home is essential

And I ain’t got one

It’s a human right

But do they even think I’m human

It’s a necessity

But they have been trying to make me disappear

Give me a bus voucher

Just to end up homeless

On somebody else’s streets

But that’s life right.

I have air, but nowhere to sleep

Nowhere to eat

Nowhere to sigh

Nowhere to talk

Cause no one is listening

The price of talking has gone up

And the value of this body is always on the decline

My friends have come and gone

I’ve lost the place where I belong

And Granny won’t be here too long

Got a list full of medical bills

A cabinet full of medical pills

And they wonder why we say poverty kills.

At the city level, Richmond is guided by a number of plans that are mandated by state and city laws, including the Housing Element of the General Plan, the Zoning Update Ordinance, the Regional Housing Needs Allocation, and Health in All Policies. The details of these plans are further concretized through local level policy and action. In the past five years, Richmond voters and City Council members passed a series of housing laws and initiatives that support a more equitable housing landscape. These efforts are frequently initiated by community organizations and have passed both by council approval, and at the ballot. While passage of such plans and policies is a critical step, the manner in which they are implemented is shaped by the priorities, resources, and capacity of city government, city residents, organizations, developers, and other actors. These actions ultimately dictate the scope and impact of existing policy on the community.

This section serves as a reference for community advocacy in identifying and prioritizing the elements of these documents that promote a comprehensive housing effort that advances belonging.

Guiding Laws and Plans

The Housing Element of Richmond's General Plan

The Housing Element lays out how the city will plan to meet the housing needs of all economic levels of Richmond’s population based on projected growth and development (see following section on how this projection is calculated). The current Housing Element was adopted in 2015 and includes an analysis of Richmond’s housing characteristics, including identifying priority development areas and vacant land maps. The Housing Element also states the city’s goals, policies, and programs through 2023 as related to housing. Community engagement in the development of the Housing Element and community efforts to ensure that policies and programs are implemented can help shape the outcomes of this plan. The four housing goals identified in the Housing Element are:

-

A balanced supply of housing

-

Better neighborhoods and quality of life

-

Expanded housing opportunity for special needs groups

-

Equal housing access for all

While broad in scope, the goals are attached to specific programs that identify concrete actions and timelines on some items. This includes actions such as the amendment of Richmond’s Accessory Dwelling Unit ordinance, an Inclusionary Housing Ordinance study to establish impact fees for new developments, which has been completed but the results have not been made public as of the publishing of this report; and a Housing Access and Discrimination study, which has not been initiated yet.

More information

-

Planning Department, City of Richmond, 510-620-6706

-

5th Cycle Housing Element Update, City of Richmond: http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/DocumentCenter/View/31210

The Zoning Ordinance

Passed November 2016 by Richmond City Council

The Zoning Ordinance brings Richmond’s zoning codes into alignment with the City of Richmond General Plan and is required by state law. The ordinance covers all of the rules that govern where in the city different types of developments can be built. The ordinance regulates everything from the proximity of types of development (e.g. heavy industrial in relation to residential) to the scale and density of developments, parking requirements to parks, and transit routes. Discussed in other areas of this report, the ordinance also covers accessory dwelling units, the affordable housing density bonus, inclusionary housing, and in-lieu fees.

More information

-

Planning Department, City of Richmond, 510-620-6706

-

Zoning Ordinance update online: http://www.zonerichmond.com/welcome.html

The Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA)

RHNA guides the creation of the Housing Element by identifying the total number of units, at different income levels, that a city must plan for in a seven year cycle. Richmond’s housing allocation is identified out of a total regional need. The regional need, in this case the nine-county Bay Area, is identified by the state, while the local allocation is identified by the Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission in accordance with the state’s Sustainable Communities Strategy. While setting local goals, at a regional level the RHNA also clarifies who is building enough and who isn’t, and at which income levels of affordability. In Contra Costa, Richmond has been one of the leaders of the development of low-income housing, but has lagged on middle-income and market-rate production—a result of a complex set of factors that include land value, construction costs, availability of affordable housing tax credits,72 rental prices, and perceptions of Richmond. In addition, research shows that in the current RHNA cycle, cities with higher percentages of white people are allocated fewer low- and moderate-income properties than their more diverse counterparts, raising legal questions about the racially disparate impact of the RHNA process.

As of January 1, 2018, new state legislation went into effect that streamlines some multi-family housing developments if jurisdictions have not permitted the target number of very low-, low-, or above moderate-income housing units.73 ,74 Richmond is a jurisdiction that has not reached any of its allocations for these three income categories during the most recent reporting period; for example, during the 2007-2014 housing needs cycle, Richmond permitted 19 percent of its very low-income allocation, 45 percent of its low-income allocation, and 57 percent of its above moderate-income allocation. As a result, any proposed multi-family developments with more than 10 units will be subjected to “streamlining” if they conform to the zoning regulations for the project area, meaning that the project cannot be subjected to additional reviews by the planning department or city council and it will automatically be permitted. These developments, however, will be required to have a minimum of 10 percent of their units dedicated to families earning below 80 percent of area median income.

More information

-

Planning Department, City of Richmond, 510-620-6706

-

Unfair Shares: Racial Disparities and the Regional Housing Needs Allocation Process in the Bay Area. Heather Bromfield and Eli Moore. August 2017. http://belonging.berkeley.edu/unfairshares

Health in All Policies

(HiAP) is a Richmond City ordinance that identifies health equity as a city priority. An outgrowth of community advocacy to include a Community Health and Wellness chapter in Richmond’s General Plan in 2006, the HiAP ordinance and strategy was drafted out of 14 community workshops with residents and the city.75 The policy builds on public health research that when it comes to health outcomes, “your zip code matters more than your genetic code,” and that cumulative toxic neighborhood stressors damage the immune system in multiple ways.76 The ordinance and strategy document includes a wide array of place-based guiding actions, including ones tied to expanding housing stability and quality. The implementation strategy is organized around six areas that reflect opportunities for addressing toxic stress and increasing health equity. One of these six areas addresses the “Residential and Built Environment” and includes a set of housing actions. Some of these that have been met include the establishment of a vacant property registry, proactive code enforcement to address abandoned and vacant properties, and an amended Housing Density Bonus for developers including housing for senior citizens or affordable to moderate-, lower-, very low-, or extremely low-income persons.77 Long-term actions which have not yet been addressed include Action 4H: Develop homelessness prevention program and enhance temporary and emergency shelter for families.

More information:

-

Richmond City Manager’s Office, 510-620-6512

-

Jason Corburn, Department of City and Regional Planning, UC Berkeley

-

Health in All Policies documents, including the ordinance, report, and strategy document: https://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/2575/Health-in-All-Policies-HiAP

Recent Housing Policy Developments

Richmond Fair Rent, Just Cause for Eviction, and Homeowner Protection Ordinance

Passed by popular vote, November 2016

What is it? The law establishes “Just Cause for Eviction” requirements for all rental units in the City, and sets a “Maximum Allowable Rent” for multi-family housing built before 1995. Just Cause for Eviction laws make it such that a tenant can only be asked to move out for specific “just causes.” In some instances, such as if the owner wants to move into the property, or needs to complete substantial repairs, the landlord must provide relocation payments to the tenant(s).

The Maximum Allowable Rent is equal to the base rent (the rent on July 21, 2015 (or the first time a tenant paid rent if they moved in after that date) plus the annual change in the consumer price index (historically around a 3 percent increase per year). For example, for tenancies that began before September 1, 2015, the Maximum Allowable Rent is equal to the base rent plus 6.56 percent. This 6.56 percent includes compounded 2016 and 2017 Annual General Adjustments (3.0 percent and 3.4 percent). Any rent increases (for tenants living in rent-controlled units) in excess of 6.56 percent are illegal. Landlords and tenants may submit a petition to the Rent Program to be granted an increase or decrease in the Maximum Allowable Rent, for reasons such as capital improvements or habitability issues.

The Rent Program’s hearing examiner, or “judge,” will make a determination of how much the rent can be increased or decreased due to the unit’s conditions. Tenants and landlords may appeal the hearing examiner’s decision to the city’s five-member rent board. The ordinance also requires landlords file all rent increase and termination of tenancy notices with the city. A landlord’s failure to file these notices with the city may be used by the tenant as a defense in an unlawful detainer (eviction) lawsuit. Finally, the law establishes a five-member rent board, responsible for hearing appeals to petitions and complaints, approving the Annual General Adjustment (AGA) rent increases, and making important policy decisions about additional fees and policy implementation through the adoption of rent board regulations, which seek to further interpret and implement the ordinance. The Rent Program budget is funded through the Rental Housing Fee, which must be paid annually by all landlords.

Effects? The rent control section of the law covers approximately 10,800 units, or about 60 percent of the city’s total occupied rental units. Just Cause for Eviction covers all rental units in Richmond. Rent control appears to slow the loss of units affordable to low-income renters; Berkeley (with rent control) saw a 26 percent decline in units affordable to low-income renters between 1980 and 1990, while the decline was twice that rate in Alameda County and in the nine-county Bay Area region.78 In addition, evidence shows that rent control does not slow the production of new housing.

Limitations? A California state law known as the Costa-Hawkins Rental Act prohibits rent control on any housing built after 1995 and single-family homes and condominiums built in any year. In Richmond, Costa-Hawkins covers approximately 7,188 existing units,79 and would apply to any new construction. As of November 15, 2016, 1,415 market rate units are in the pipeline.80

Implementation priorities. Raise awareness and inform tenants of their rights. A stronger public campaign can help tenants to challenge illegal rent increases and evictions, and win rent rollbacks on rents raised more than 6.56 percent between July 21, 2015 and 2017.

Expand access to legal representation for unjust evictions. The rent board adopted a budget that includes $150,000 for legal services contracts for housing issues, with services expected to begin in early 2018. This will fill some of the gap between tenant legal needs and available services. The gap mainly affects those who cannot afford private representation but do not qualify for free legal representation. Even for those who qualify for free legal aid, capacity is highly limited. For example, Bay Area Legal Aid which has a location in Richmond had only one housing attorney for all of Contra Costa County until late 2017.

Establish Fair Return regulations and all regulations necessary to administer petition process. The petition process continues to have a number of details that need to be clarified in order to regulate the process. For example, if a tenant hasn’t had heat for two months, what type of rent reduction is warranted? If a landlord makes major upgrades like a new foundation or roof, how much of a rent increase is justified?

Public participation at rent board meetings to ensure the most equitable implementation of the law. The rent board meets on the third Wednesday of every month at 4 p.m. in the City Council Chambers (440 Civic Center Plaza. Minutes and agenda packets can be accessed via http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/3375/Rent-Board

Support statewide organizing efforts to repeal Costa-Hawkins.

More information

-

City of Richmond Rent Program, 510-620-6576 or rent@ci.richmond.ca.us, located at 440 Civic Center Plaza, 2nd Floor. To learn more about the rent program, rent board, and access recently adopted regulations and resources, visit www.richmondrent.org.

-

Tenants Together, 415-495-8100. Tenants Together and Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment host a monthly clinic in Richmond, CA on the 2nd Wednesday of each month at 6 p.m. - ACCE Contra Costa Office: 322 Harbour Way, #25 Richmond, CA 94801

-

The ordinance: http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/DocumentCenter/View/41144

Relocation Requirements for Tenants of Residential Rental Units Ordinance

Passed by City Council, November 2016

What is it? The ordinance, which was required by the Fair Rent ordinance, outlines the requirement of temporary and permanent relocation payments by landlords to tenants. Temporary payments are required when a landlord needs to make substantial repairs to bring a unit into compliance with codes and laws regarding health and safety. Permanent payments are required in the case of owner move-in (OMI) or the withdrawal of the unit from the rental market. Tenants have a right to return if the unit later returns to the market.

Effects? The ordinance covers all rental units in the city. It creates financial support for tenants who must move for the above reasons. These practices are commonly employed by landlords in other local cities with rent control and just cause for eviction ordinances. The amount of payment is determined periodically by a resolution of the city council.