On Tuesday, June 22 we hosted a half-day forum with fair housing advocates and leading race and housing scholars from across the United States for the unveiling of "The Roots of Structural Racism," our groundbreaking new project which details just how widespread and harmful racial residential segregation remains today, why it matters, who it impacts, and what can be done to reverse this dangerous trend and promote integration. More than half a century has passed since the enactment of the 1968 Fair Housing Act which officially outlawed discrimination in housing, a key victory of the Civil Rights Movement. But new research set to be released during this event shows that in far too many cities, segregation has in fact increased, with deeply consequential impacts in terms of people's physical and mental health, access to well-performing schools, job opportunities, exposure to violent police, and overall life outcomes.

Speakers at this event included:

- Richard Rothstein, author of the best-seller The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

- Lisa Rice, president and CEO of the National Fair Housing Alliance

- Demetria McCain, fair housing advocate and president of the Inclusive Communities Project

- Margery Turner, expert on urban policy and neighborhood issues and fellow at the Urban Institute

- Ajmel Quereshi, Senior Counsel at the Legal Defense Fund; john a. powell, OBI director and housing expert

- Stephen Menendian, OBI assistant director who led the Roots of Structural Racism project

- Samir Gambhir, director of OBI's Equity Metrics program, and co-author of The Roots of Structural Racism project.

This event was organized by the Othering & Belonging Institute and co-sponsored by the National Fair Housing Alliance, the Inclusive Communities Project, Race Forward, the Poverty & Race Research Action Council (PRRAC), California Housing Partnership, the Urban Displacement Project, Fair Housing Advocates of Northern CA, the National Housing Law Project, the Anti-Discrimination Center, the Thurgood Marshall Institute at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Berkeley Geography, African American Studies at UC Berkeley, and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation.

Event Transcript

Marc Abizeid:

All right. Looks like we're getting started. Hello everyone. Sorry. We're a couple of minutes late. We had just a couple of issues in the background. I want to welcome everyone. My name is Marc Abizeid. I work here at the Othering & Belonging Institute with my colleagues, Stephen Menendian and Samir Gambhir, and we're super excited today to launch our groundbreaking national segregation project. This project includes a powerful new mapping tool, which is one of the most comprehensive efforts ever to investigate the persistence of racial residential segregation in the United States. So as we'll discuss, this project has led to some startling, even disturbing findings about ongoing racial segregation in the United States, but it also offers tools that advocates can use to reverse this trend. So let me introduce Stephen Menendian and Samir Gambhir, who led the effort to launch this project.

Marc Abizeid:

Stephen is the Othering & Belonging Institute's, assistant director. He's written extensively on the patterns and impacts of racial residential segregation in the United States. Samir is our equity metrics program director and the technical expertise who helped bring this project to life. I also just want to acknowledge the project's third author, Arthur Gailes, who's, unfortunately, unable to join us today. So just a quick thing about our format. This Q&A session is going to last probably about 20 minutes, followed by two additional panels later in the day. And those panels include some serious heavyweights in the arena of fair housing, and civil rights. So we'll hear from them about why segregation still matters today and what we can do about it.

Marc Abizeid:

We have the full agenda on our website, and you can go to that just by going to belonging.berkeley.edu. And it will be the first thing or maybe the second thing you'll see on our homepage. Also, if you're tuning in from YouTube and Facebook, please be sure to type in your questions in the little chatbox. And if we have time at the end of this first panel, we'll try and get to some of them, but definitely, we'll get to some of them in the second and third panels. So let's just get started. Stephen and Samir, thank you so much for joining. Let me first ask Stephen, what led you to this work? And why did you decide to look into housing segregation in the first place?

Stephen Menendian:

Thank you, Marc. It's great to be here with you and Samir and Nicole and our other interpreters. We had a little bit of technical difficulties getting started because our original moderator's audio went kaput, and then computer went down. So thank you, Marc, for stepping in at the last minute. I was reflecting this morning that Samir and I, we've been colleagues for so long. Haven't we, Samir?

Samir Gambhir:

Sure.

Stephen Menendian:

And Samir and I were both hired at the Kirwan Institute, around the same time by john powell in 2005 and actually Samir, I believe you started the week Katrina hit New Orleans.

Samir Gambhir:

That's correct.

Stephen Menendian:

As I look back on the work, we've done over the preceding decades. Katrina is one of the most important events I think of this century. And I think it was the first event really that Joe Biden likes to use the term the blinders fell off, that the blinders really fell off on race, where we began to see that what was happening with racial inequality in the United States was far beyond the way in which we had previously understood it. That is why were African-Americans disproportionately impacted by Katrina? And the answer we came to was really that it was partly segregation.

Stephen Menendian:

It was why African-Americans disproportionately living in the Lower Ninth Ward on the flood plain, in the damage of flooding in the path of the destruction by Katrina. And you may remember Kanye West had this really famous saying that George Bush doesn't care about black people as the images of people were behind him, right during the telethon. And I think there was a contrast. There was a moment, a really important moment, where Kanye was articulating the interpersonal conception of racism in a context in which structural racism was fully manifesting itself.

Stephen Menendian:

And so I think our work, Samir and I have worked in the rest of that decade, we worked with school districts, we developed student assignment policies. We worked on disciplinary policies and rolling back zero-tolerance punishments on curriculum and teacher recruitment and retention. And we did everything we could. We ended up working on affirmative action cases, filing Amicus briefs in the Supreme court in the two Fischer cases. But in every one of those instances, the Texas 10% plan for those of you who aren't familiar with it. What it does is it essentially promotes diversity in the University of Texas at Austin because of underlying segregated housing patterns. That is to say, it takes the top 10% roughly of graduating seniors from each public high school and automatically mixed them to UT Austin. But the reason that promotes diversity is because of the underlying patterns of racial, residential segregation.

Stephen Menendian:

So everything we're looking at--health, the criminal justice system--john ended up hiring Michelle Alexander around 2008, 2009. And she was working on her book. Every issue we were looking at was undergirded, and then COVID pandemic. What were the neighborhoods that were first hit hardest by this pandemic? In California, it was very clear that Hispanic community was hit hard around the rest of the country in the first wave. It was usually black neighborhoods. In New Orleans and Chicago, and elsewhere. All of this is undergirded by racial, residential segregation. You can't make sense of why some communities are harassed, surveilled, aggressively policed without actually looking at where people live because where people live determines essentially every aspect of their life.

Stephen Menendian:

There was a story in the Washington Post last week about the mortality rates from COVID being a product of segregated hospitals. The hospitals that people have access to are close to where they live, and it wasn't that the care was worse in those hospitals. It was the conditions. It was the funding levels. It was these instruments and so on. So we just kind of fell into this. Samir, we were working on other issues and realize this is really the core issue.

Marc Abizeid:

So Samir, could you tell us a little bit about the findings that you discovered during the course of this project and the report and what you found most surprising about them?

Samir Gambhir:

Sure. So as Stephen mentioned, racial, residential segregation is and has been a mechanism to exacerbate racial inequality. In our analysis in this project has been illuminating, and we've laid out our key findings in the web report, but I'll try and summarize those in three categories. One, we looked at the trends in segregation, number two, analyzing the harms of segregation and looking at the relationship between political polarization and redlining. Our analysis, when we look at the trends, our analysis reveals that more than 80% of our metros in the nation are highly segregated as of 2019 than they were in 1990. In the same time period, the diversity has grown, but unfortunately, that diversity has not translated into integration. Additionally, Rust Belt cities of the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic, such as Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, these feature as the top 10 most segregated cities in the nation. Not surprising Midwest and Mid-Atlantic regions also turn out to be really highly segregated.

Samir Gambhir:

On the analysis side, we see that neighborhood poverty in segregated communities of color is three times higher than in segregated white neighborhoods. Additionally, black and Latino kids raised in integrated communities they earn more than those raised in segregated communities of color highlighting that racial residential segregation is a structural problem. Not surprisingly, median household income, home values, and homeownership rates in segregated white communities is much higher than segregated communities of color. Likewise when you look at the relationship between segregation and political polarization, we see that higher levels of segregation correlate with higher levels of political polarization. The relationship is not causal, but this can lead to political gerrymandering.

Samir Gambhir:

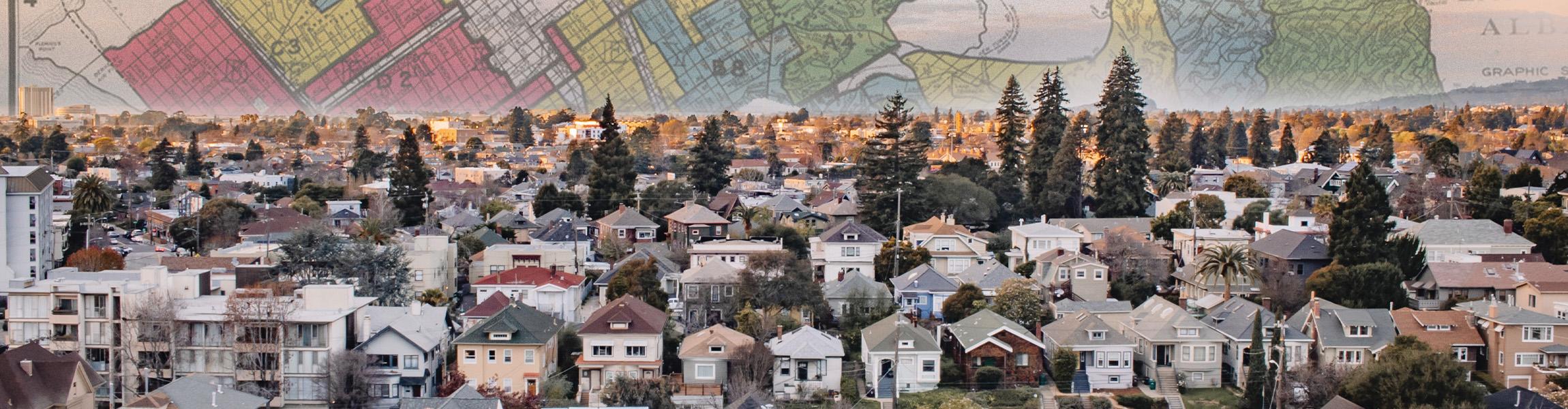

Additionally, we see that more than 80% of our neighborhoods, which were redlined around the 1930s by the federal mortgage policy, turned out to be highly segregated using our 2010 data. So all these are some of the highlights of the findings that we have in this report, but there'll be more. I'll request people to dig into the report and see more. To your question on what are the surprising findings is, the most surprising finding is that the racial residential segregation is still really pervasive. We applied our functional integration measure and the segregation measure to 213 largest cities in the nation. And you'll be surprised to know that only two cities showed up as integrated. This clearly shows that the racial residential segregation is really deep-rooted.

Marc Abizeid:

Thank you, Samir. We only have a few minutes left. Stephen, maybe you can tell us a little bit about this web mapping tool and how you think researchers or housing justice advocates can use it in their work. And what's so special about it. What's different about it from other maps?

Stephen Menendian:

Well, this project is so multifaceted. There's so many interesting components. We have kind of a lit review of local histories of segregation. We have the city snapshots of places we want to highlight. We've got the report and components, but the interactive mapping tool is really the centerpiece of this project to try and illuminate the actual extent of segregation. Unfortunately, over the last 24 hours, because of the media attention, our map crashed last night, and it's been a little buggy this morning, so don't rush to it. Just give it a few days for us to figure that out. But we actually did, for a media briefing last week, we have a small clip I'd like to show. Before that, let me just explain a little bit about what it is. So you're going to be able to use this map to see racial composition, to see the level of segregation and the types of segregation.

Stephen Menendian:

And you can go back and forward in time. So Marc? This is our mapping tool to really show how segregation is occurring across the United States. And let me do a little bit of a zoom-in here. The default map layer actually it divides the country into three areas, highly segregated, low to medium segregation, and racially integrated. And I think what you can really see here is that United States continues to be a place of segregation, not integration. And we can tell exactly how we define that in a bit. We've done so much with this project. We've taken the digitized hook, redlining layers from the 1930s, and we put them into this map. We have the segregation stories from some of the most segregated and most integrated places in the country. We have the ability to change the year over time.

Stephen Menendian:

So you can see the change in the level of segregation, and for housing advocates and experts, you can actually choose between one of basically 35 different measures of segregation. So let me just show you a little bit of an example of how this can work. So let me go into some census tracks. Actually, I'll do the address search, take us into Oakland, Bay Area, which is one of the most diverse regions of the country. Oakland, in fact, it's almost one of the most diverse places in the world, just so you can see how segregated it really is. So this is the Bay Area, the core of the Bay Area. This is East Oakland. These census tracts right here are in the 94th percentile, most segregated. You can see here. It actually gives you our divergence index score. And for each track, you can see the racial composition.

Stephen Menendian:

You can do this, by the way, for anywhere in the country, you can see exactly how segregated it is. You can see the racial composition. You can actually see the change over time. We've also done some interesting disaggregation. You can change the geography from the city to the tract, the Metro area here. I think what you might also be interested in is seeing we changed the measure back to our default. There's a lot here. We've actually disaggregated here between highly segregated, white neighborhoods and highly segregated communities of color, which this more detailed view allows you to see.

Stephen Menendian:

So these neighborhoods up here in Contra Costa County and the suburbs of Oakland, and up here in Marin, these are exclusionary white enclaves. They have the most significant investments in wealth and resources. And these are places where opportunity can culminate. And these are places where many, many kids of color are excluded people of color. So you have lots of Latino, black, and Asian communities and this corridor. And then these are where white people live. So this mapping tool allows us to see segregation in a much more detailed way than it's ever been done before.

Marc Abizeid:

You want to elaborate any more on that map, Stephen?

Stephen Menendian:

Well, we have, I think, high hopes that ordinary people will use the map and find their homes and look at their communities and see how they've changed over time. We hope that fair housing advocates can use it to sort of plug in the numbers. If fair housing advocates or affordable housing advocates are trying to look to see whether a proposed affordable housing development will promote integration or promote segregation. We want people to be able to use the tool without having to hire an expensive $500 an hour expert to get that data. So we are trying to make this publicly accessible so that people have this data and information at their fingertips. I think very useful for journalists as we've seen, we had. I think it was some 50 different stories written about it yesterday and policymakers who want to better understand this issue. And we're going to have some folks in the next few panels who are going to talk about this problem of persistent racial, residential segregation and how it affects these other arenas of life.

Marc Abizeid:

The last question I have for you guys is, talk a little bit about this core of the problem that you see is segregation. It's not necessarily just one of being able to equalize resources. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Stephen Menendian:

It's interesting doing all these interviews the last few days. One of the questions that comes up is what do we mean by segregation? When you say segregation, a lot of people think of Jim Crow type segregation, where you think of public accommodations, you think of separate seating on buses and trains or in restaurants and theaters or pupil assignment in schools. Students by law being sent to black schools or white schools in the Jim Crow's style. When we're talking about segregation, we're talking about something that's quite different. In the 20th century, there was an evolution, especially as during The Great Migration, as African-Americans moved West to the shipyards and war mobilization factories of the North, the steel factories of Pittsburgh, and the car factories of Detroit and out West the rest of the country segregated. But we didn't segregate in a Jim Crow style. We are segregated by where people live.

Stephen Menendian:

African-Americans were only permitted to move into a small number of tightly bound neighborhoods. And those are places that we know in the Bay Area, it's a Hunter's Point. East Oakland, East Palo Alto. And so where people live shapes everything, right, shapes their access to opportunity. But the kind of segregation we live with in the 21st century has evolved yet again. It's no longer about a small number of tightly defined neighborhoods. It's now about a regional pattern. Places like Ferguson, the 1970 were mostly white, today are predominantly black.

Stephen Menendian:

And so we need to be sensitive to the evolution from public accommodation segregation to residential segregation, which by the way, by 1940 was firmly entrenched around the whole country to this new form of segregation, which is really about the municipality you live in, the tax base, the quality of public services, the environment. You live in a place that has healthy and safe drinking water or a place like Flint that can't afford to upkeep the infrastructure or is put under state receivership, like Detroit or Newark that's crumbling schools or mold in the schools. One of the things that I did a lot of work on in the arts was looking at water access, and it's become important again today. So all of these things are really the core of what we mean by systemic and structured racial inequality in the United States.

Marc Abizeid:

We actually have an interesting question from the audience. Let me just put it up on screen and get your thoughts on it. How can school districts use the interactive map to generated policies that create equitable learning conditions?

Stephen Menendian:

One of the things that's unique about our map is it's looking at where people live rather than the schools they attend. But we know that when we talk about segregation, it's mostly in the context of schools because look in New York City, New York City is 75% African-American and Latino students. And it's 70% students on free and reduced lunch. It's one of the largest school districts in the country. It's highly segregated. So in the context of schools, that's the area in which we actually recognize that segregation is harmful, but we don't really talk about it nearly as much in the context of housing. So this map is unique in that we're actually displaying free of charge to the public and hopefully a user-friendly way, the ability to look at segregation and racial composition by housing. There are already plenty of excellent maps for how for school segregation.

Stephen Menendian:

In fact, there are three that I can think of. One is created by Sean Riordan on Stanford. I forget the exact name of it. I think it might be at Build, and there's also another one that Vox created. And a third one, I can't remember the source, but I can dig it up, and we can post a link to it somewhere where you can actually search for a school district and search for a school. And you can actually see to what extent does the surrounding neighborhood create segregation in the school? Or to what extent is your school segregated? And it also includes test scores. So you can see how different racial groups disaggregated by gender as well are performing in those schools. So there are excellent mapping tools for school researchers or people who are working with school districts to help improve and create more equitable learning outcomes. We didn't want to duplicate that. We're trying to supplement that. I would direct your attention to those other mapping tools.

Marc Abizeid:

Here's really quick one, I can't remember if you went over this or not, but Xochitl wants to know if the map shows change over time.

Stephen Menendian:

Definitely, as we showed in the video, very briefly, you can actually toggle from 1980 to 2019. So we have all the decennial census data there, and you can actually observe the change over time that the DC article that covered us yesterday in the media section did a phenomenal job showing change in DC over time. Samir, do you want to add anything before we wrap?

Samir Gambhir:

Well, I just wanted to say that we have also curated a number of stories, segregation/integration stories that are embedded in the map. So those are also very interesting, and we have some histories as well. So if our users can dig into that, that'd be a good resource as well.

Marc Abizeid:

All right, great. So it looks like we're running out of time on this panel. We have a ton of more programming scheduled for the rest of the day. Stephen and Samir, thank you so much for presenting the project. I'm sure there's tons of housing researchers, advocates, and journalists out there who are going to make really good use of this project. And if anyone wants to get in touch with us, please email us at belonging@berkeley.edu. And so right now me and Samir are going to head out. We're going to put a little two-minute intermission card, and then Stephen is going to be back moderating the next two panels that are going to come up in just a couple of minutes. So thank you, everyone. And we'll see you soon.

Samir Gambhir:

Thank you everyone.

Stephen Menendian:

Welcome back, everyone. I am thrilled to be here with everyone. I'm going to introduce our phenomenal panelists here. So starting from below me on the other screen is Richard Rothstein, who is the senior fellow at the Othering & Belonging Institute, and a Distinguished Fellow of the Economic Policy Institute, where he works on policy and procedures regarding race and education, and a senior fellow emeritus at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He's perhaps best known as the author of the 2017 bestseller, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, which recovers a forgotten history of how federal, state, and local policy explicitly segregated metropolitan areas, nationwide creating racially homogeneous neighborhoods and patterns that violate the constitution and require remediation.

Stephen Menendian:

Next, we have Margery Turner, who is a fellow at the Urban Institute and a nationally recognized expert on urban policy and neighborhood issues. She's analyzed issues of residential location, racial and ethnic discrimination, and its contribution to neighborhood segregation and inequality, and the role of housing policies in promoting residential mobility and location choice. She's also the author of the book Public Housing and the Legacy of Segregation. Marge previously served as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Research at the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, HUD, from 1993 through 1996, focusing HUD's research agenda on the problem of racial discrimination, concentrated poverty, and economic opportunity in Americans metropolitan areas.

Stephen Menendian:

And we have my boss, john powell here, who is the director of the Othering & Belonging Institute and a Professor of Law and African-American Studies and Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley. He is an internationally recognized expert in the area of civil rights, civil liberties, structural racism, housing, poverty, and democracy. He is the author of several books, including his most recent Racing to Justice: Transforming Our Conceptions of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society. And he was the lead expert witness in the landmark case of Thompson vs. HUD and the co-creator of the opportunity mapping framework. Welcome, everyone. So I'd like to start with a simple question. Deceptively simple: Does racial residential segregation matter today, and if so, why? Marge, why don't we have you kick us off?

Margery Turner:

Sure. Thanks. Thanks. And I just want to start by congratulating your whole team on this terrific product, huge sprawling and incredibly valuable product. And I see it as so important because I really share your view that our history of residential segregation in the US and the persistence of residential segregation across the whole country. It's produced a system of neighborhoods that are not only separate but structurally unequal in terms of schools, in terms of health, in terms of access to food, parks, and recreation, environmental quality access to jobs, and policing practices.

Margery Turner:

And so those neighborhood disparities are driving inequity in absolutely every other dimension of our lives, safety, health, education, employment, wealth building. They're undermining people's quality of life day-to-day. They're blocking people's access to upward mobility and opportunities for success and progress. And I think they are passing harms from one generation to the next. So this is fundamentally important to equity in our country and the future of our country.

Stephen Menendian:

Thank you. Richard?

Richard Rothstein:

I second everything that Margery just described. Perhaps I can just give a little bit of specific illustration and the framework that she just presented. Let's talk about education for a minute. As you know, we have a big achievement gap in this country between black students and white students. On average, African-American students achieve at much lower levels than white students do. And the primary reason they do so is because they are concentrated in neighborhoods of severe social and economic disadvantage. And then their schools are overwhelmed by the problems that they bring to school. And they're unable to give them the kind of instruction that they deserve. And they're unable to take advantage of that instruction.

Richard Rothstein:

So, for example, as you probably know, in many of the highly segregated neighborhoods that you've described in this mapping exercise, African-American children have asthma as much as four times the rate of middle-class children. And if a child has asthma, that child is more likely than the child who does not to be up at night wheezing and then come to school drowsy the next day. And if you have two groups of children who are identical in every respect, except one group has a higher rate of asthma than the other, that group is going to have lower average achievement by a very small amount because it's drowsier.

Richard Rothstein:

Well, asthma is not the only condition that is disproportionately present in segregated neighborhoods. Lead poisoning, lead poisoning has a measurable impact on IQ, and lead poisoning is a much more prevalent in black urban neighborhoods because there are more ancient pipes, lead line pipes that are bringing water to people's homes, more flaking paint from homes that were painted up prior to the abolition of lead-based paint, homelessness, much more prevalent in low income segregated neighborhoods, economic insecurity. You begin to add all of these up, and you pretty much explained the achievement gap, and then when you concentrate children in schools where every child has one or more of these conditions, it's impossible for a school with that kind of concentration and disadvantage to give the attention to instruction that it would in a school with children who came well rested, healthy, well-nourished from economically secure homes.

Richard Rothstein:

So that's just one illustration of how segregation creates the enormous educational problems that we have. I'll give you one other, and I'll stop up. Margery mentioned health. Well, African-Americans, as you know, have shorter life expectancies on average than whites, greater rates of cardiovascular disease. That's partly attributable to the fact that they live in low-income, segregated neighborhoods. More diesel trucks driving through more trucks, driving through their neighborhood, polluting the air, more stress, less access to grocery stores that sell fresh food. If we didn't have such segregation and such concentration of disadvantage and the hostile environmental conditions, the African-American life expectancy and cardiovascular rates should not be as much different from whites as they are today. So those are just two examples that illustrate what Margery so eloquently described.

Stephen Menendian:

Thanks. john?

john a. powell:

Thanks for the question. I add to Marjery's congratulations to the team and Stephen for pulling this together, and it's great to be with Margery and Richard. So the short answer is it's extremely important as this report documents. Segregation is a way in which we distribute opportunity. Oftentimes, we think of segregation, we think of it in racial terms or even religious terms. So it's like one racial group separated from other racial groups. And oftentimes, that's part of it. But segregation is how we distribute opportunity. And one of the reasons in as your report shows quite segregated areas along a number of indicators actually are doing better, not just in black segregated areas, but sometimes better than integrated areas, meaning that they're hoarding more resources, hoarding more wealth, hoarding higher incomes. So the whole idea of segregation, not necessarily fully conscious, is how do people distribute opportunity?

john a. powell:

And you could do it at an individual level. And we do that, but that's inefficient, so segregation makes creating inequality efficient. It's an efficient way of actually replicating inequality. At a deeper level as well... So we need to think about segregation as segregation from opportunity, not just segregation from people. How do we separate people, certain groups of people, from opportunity? The kinds of things that Rich and Marge already talked about. But it's also doing more work than that. It's also distributing identity itself. In the social science, most social science agree that race is socially constructed, but almost no one pays attention to how it's constructed.

john a. powell:

And segregation plays a large role in terms of creating hard boundaries around social identities. So it really does some very fundamental work. And again, you talk about this in the report. The effort to bring opportunity to low-income disproportionately black and Latino areas is almost always, outpaced by the speed and intensity of creating inequality, creating low-opportunity by segregation. So segregation, in a sense, is more efficient at creating inequality and disparities than investing in low-income communities of color. So it's doing profound work at multiple levels, and there's virtually no reason to believe that that will change.

Stephen Menendian:

Thank you. I want to go off-script with my next question because it strikes me that we are in this unique moment of opportunity in the country where we've had what the media has called a racial reckoning last year, so there's greater public awareness of the structured role of racial inequality. I'm wondering if you could speak, I'll ask the hopeful question or the what's possible question towards the end.

Stephen Menendian:

But for now, could you speak to how you perceive the relationship between these three components, structured racial inequality, racial residential segregation, and the racial reckoning through understanding the police and criminal justice systems. What do you see as the relationships? It's an open question. Who'd like to start? Why don't we go back around, Marge?

Margery Turner:

Sure. It's really hard to focus on where the cycle starts. I think john's point of what an efficient system for separating us, making us identify with our separateness, and distributing both opportunity and threat or danger very efficiently and inequitably, this is a profound point, and it is not clear to me, as I listen to renewed attention to racism and the structures of racism, which is encouraging, I don't hear enough attention to these profound patterns of where we live, where our children grow up, where we have our friends and relationships.

Margery Turner:

I hope that the tool that you've developed brings more attention to the tremendous impact and damage that residential segregation is doing and helps people understand that if we genuinely care about promoting racial equity in our country going forward, we've got to knuckle down and dismantle this system of separate and unequal neighborhoods that we've built.

Stephen Menendian:

Richard. You're muted.

Richard Rothstein:

Well, I mute myself. Can you hear me now?

Stephen Menendian:

Yes.

Richard Rothstein:

Okay. You mentioned structural racism, and it's a term that most people don't understand. I think it's important to make it concrete, so let me give you an example of how it works. One of the ways it works is that once you have two separate and unequal communities, any policy that you implement, any practice you implement is going to affect those two communities differently, and not necessarily to the disadvantage always of African-Americans, but almost always to the disadvantage of African-Americans.

Richard Rothstein:

For example, recently there's been a lot of attention paid to the fact that the property assessment system in this country, and almost every community in this country causes African-American homeowners to pay higher property taxes relative to the value of their home than white homeowners pay relative to the value of their home. This is not because of racially explicit policies, it's structural racism. It's because any property tax system that you adopt almost negatively is going to affect black and white homeonwers differently.

Richard Rothstein:

For example, if you don't reassess properties every year, on a regular basis, if white neighborhoods are appreciating in value faster than black neighborhoods, property assessments in black neighborhoods are going to be closer to the real market value of homes in those neighborhoods than property assessments in white neighborhoods, which are going to be much lower than the real market value of homes in those neighborhoods. It's what the lawyers call a disparate impact of a race neutral property tax assessment system, and there are many, many other reasons why this happens.

Richard Rothstein:

That's what I think you mean by structural racism. Once you have two separate communities with different social-economic characteristics, any race neutral policy is going to have different impacts on each of those communities and in many cases, like the property assessment system, it's going to be much worse on African-American communities than on white communities.

Stephen Menendian:

john.

john a. powell:

Again, agreeing with Marge and Richard, I think the reckoning, the focus on race is actually a positive thing, but there are also, from my perspective, some serious blind spots, and probably even some negative. One of the ways, what happened with George Floyd and Derek Chauvin, important really awakening for the country, but to some extent, not entirely, but it focused on a police officer and the police, not on the larger system.

john a. powell:

There's some, as people talk about the qualified immunity for police and things like that. But there's been a lot of data, including in your report, showing that the black community is policed different than the white community. That there's more likely to be killings in certain communities, so that's spatially. There's a geographic dimension to this that moves beyond just the training of the police or even the police department.

john a. powell:

Several years ago, I was involved in a study looking at racial profiling. Again, very geographic, and some people explain the disproportianate focus on blacks by saying, "Well, blacks are more likely to be in the streets. They may use drugs at the same rates as whites, but they're more likely to be in the streets, in terms of using theirs, while whites are more likely to be in a house."

john a. powell:

Turned out, that's not an explanation. Because in part, the greatest disparity in profiling was when blacks wandered into upper-middle class white communities or lived in those communities, because there was an assumption that those communities are for whites. Literally, it's like people could stop. Why are you in this community? I've been stopped asking, what am I doing here? Not because I was veering in traffic, but it's like just visually.

john a. powell:

I think it's great there's more focus. I think the focus needs to be a little bit more nuanced and it does need to focus on structures. Let me just say one other this about structures, it's not that there isn't structural racism. Structures are almost always biased. Structures carry certain values and assumptions, and they're designed to do something and then the research terminology they're oftentimes built normalizing on a certain population. Think about when we were testing for AIDS, it was normalized on white males and the way AIDS showed up and acted in terms of blacks was not the same. Even in terms of tests. We found out that most recently with COVID, that the test was apparently not enough women were in the tests, women were actually being oversubscribed with the vaccine because their bodies are generally smaller, and so it had a gender bias in it.

john a. powell:

I use the example sometimes of an escalator. If you're in a wheelchair the escalator doesn't work for you. Almost all structures carry certain bias and sometimes deliberate, oftentimes it's not. One of the interesting examples, think about bathrooms at public sporting events. You see men zipping in and out because they have urinals and women are in these long lines. In California now we've said any new public arena has to be built differently. Again, it doesn't necessarily mean that someone did deliberately decided to disadvantage women, but women are disadvantaged in going to use the bathroom in half time at a sporting event in most of America, and the same phenomenon with even more so happens in terms of race and multiple reasons, sometimes it's just economic. Give one last example. Why do we overbuild low-income housing in low-income areas?

john a. powell:

Well, like I say, racism, but what also could say, housing, the land's cheap. It's like, let's look where we can build the most housing because the land is cheap. Oh, it happens to be cheap in areas which are disproportionately black, so we actually concentrate more housing in those same areas and then those kids, if it's family housing, go to schools, which are already overpopulated with kids on free and reduced lunch so that mechanism keeps perpetuating itself and we produce not just what Richard called the achievement gap, we create an opportunity gap and it's perpetuating. There's so many factors that are interrelated and it actually disadvantaged people and with a very strong correlation with race and other factors.

Stephen Menendian:

Continuing to go just off script for another question, many people care a lot about the racial wealth gap and about health outcomes and health inequalities with respect to race and that's become especially acute during this pandemic. I'm wondering if given your extensive writing and research on these topics, if you could speak to either one of those phenomenon and how it's linked to racial residential segregation. Anyone can start.

Margery Turner:

Well, I'll be glad to start with wealth. There's, I think in the introduction, Stephen and Samir talked about how black people moving to Northern and Western cities were not only constrained to live in only a few neighborhoods, but were then denied public sector programs to help buy homes and begin building wealth in those communities. That disadvantage in the early middle part of the 20th century gets passed from one generation to the next, so where white families starting from pretty modest beginnings, have been able to buy homes, build wealth, pass it to their children, buy homes in appreciating neighborhoods, escalating to the point where we can set our children up easily with wealth, transferred from generation to the next, for college, for business investment, for home ownership, black families putting in absolutely equal effort all along the way have been at a widening and widening disadvantage with respect to wealth.

Margery Turner:

The challenge then is that these inequities that we've built are really difficult to disentangle. There is no super easy fix now to expanding access to home ownership, home equity and wealth building, there's no easy fix to that. The solutions are going to have to cut across domains to repair the damage that our public policies have done, and in particular, we need to be sure that when we try to tackle segregation, we're tackling both the separate dimension and the unequal dimension, and we can come back and talk more about that later, but focusing only on remedying the separate, or only I'm remedying the unequal, I think is going to fall short.

Richard Rothstein:

But let me elaborate a little bit, if I may, Margery, it's great to have you set me up like this all the time, but let me elaborate a little bit on this wealth gap issue. As Margery pointed out in the 20th century, the federal government and the real estate industry and banks all conspired to move white working class families that weren't middle-class at the time, white working class families into single family homes and all white suburban areas. At the time, nobody had any idea that this was going to generate wealth. Nobody knew that those neighborhoods were going to appreciate in value the way they did.

Richard Rothstein:

But what happened was that the neighborhoods appreciated in value and the families who own those homes became middle-class because homes that they bought in the mid 20th century for what today's money would be about $100,000 working class homes are now, depending on the part of the country, were 300, 400, $500,000, some places, a million dollars and more, and the difference between $900,000 in the present value of the homes is the wealth those white families gained to send their children to college, to perhaps take care of temporary unemployment or medical emergencies, to subsidize their retirements and to bequeath wealth to their children and grandchildren, who then had down payments for their own home. It's a perpetuating situation.

Richard Rothstein:

However, too many policy advocates, they assume that because the wealth gap was created by this kind of home ownership, the way to fix it is to get more African-Americans into home ownership. That's partly true, but it's not nearly as true as people think. There are two ways you gain wealth from home ownership. One is if you have a longterm amortized mortgage and you stay in your home for the full term of that mortgage over time, more and more of your monthly payments are attributable to principal rather than interest and by the time of the mortgage is paid off, or you sell the home after a lengthy period of time, the wealth you have is that principle that was part of your monthly and increasing part of your monthly payments.

Richard Rothstein:

But the other part of this I mentioned before is you can gain wealth if the homes appreciate in value and that's not guaranteed. If you move African-Americans into more homeownership in neighborhoods that aren't appreciating rapidly in value, and that has been the experience of African-American homeownership. African-Americans have not gained wealth from home ownership, the way that whites have, except through this payment of an amortized mortgage. If you move into a home in a neighborhood that's not appreciating in value, you don't get that extra big boost in wealth that white families got for moving into the homes that unpredictably were in neighborhoods that were going to appreciate in value.

Richard Rothstein:

We have to think much more broadly about the wealth gap. The other way that families gain wealth is by having high enough incomes to save from their incomes and that today for African-Americans is perhaps as important a means of wealth generation as moving into homes and the hope that it's going to be in a neighborhood that's going to appreciate in value, and so we can't separate out racial policy from economic policy, so long as so many African-Americans are working in occupations where the income is too low to support substantial savings. We're not going to be able to address the wealth gap in the way that we would, if they were able to save from their incomes.

john a. powell:

Let me add my voice to this. Thank you Marge and Richard for setting me up. Stephen, I've been playing with the idea of writing something about complexity and nuance because I think that these issues are all complex and nuanced and if we understand that it not only helps us understand the issues better, but it actually helps us move to solutions so we don't make an intervention as Richard suggested and actually continue to perpetuate the problem. Let me just talk a little bit about the problem. First, it is a serious wealth gap, but it's different than we think. If you look at low-income whites, the wealth gap between low-income whites and low-income blacks is much smaller, makes sense.

john a. powell:

It becomes larger up the scale and becomes really big when you get to like 1% on top, or 0.1%. It's both a combination of race and class. You also need to look at not just private wealth, but also public wealth, so the things... To go back... If we were able to equalize the wealth between the poor whites and poor blacks, in some way, we say, "Great, now they're equally poor."

john a. powell:

I don't think that's what we want. We actually also have to look at how much wealth a healthy family society has, and we'll find that yes, there's a racial wealth gap, it's not as big at lower end as it is on the higher end, and so that draws our attention also too low-income whites. But whites, even low-income whites by and large have a different phenomenon than low-income blacks, so that's one. To Richard's point, housing has been the major vehicle for the creation of the white middle class and for the creation of white wealth in a white middle class.

john a. powell:

It's less true now for whites only, I think 49%, I think of white wealth is in housing, a much higher percent is in housing for blacks, but, and I worked on a program in St. Paul, Minnesota, where they were trying to increase home ownership for blacks ... and asked me to advise the community because the community was somewhat skeptical. After looking at it carefully I said, "Great program, you'll get to become a homeowner, but you're not going to have wealth appreciation", because the housing that the city had designated for this experiment was low appreciating housing.

john a. powell:

People said, "We're not doing that. We're not going to spend money on housing that's not going to appreciate. Why would we do that?" The city was very annoyed with me. It's like, "You talked people out of the program." I said, "No, I gave up information about the program." People assume that if you buy a house it's going to appreciate and is relatively equal. It's not. We pay, Russ talks about a segregation tax that if you live in an area that's deeply segregated, a black area, for example, that's deeply segregated, you will not only pay more in terms of taxes and other things, but it will appreciate less, and so you have to attend to that as well.

john a. powell:

As Marge said, there's so many things that are confounding. For example, a case I worked on was American family. It was basically looking at insurance companies refusing to insure homes in segregated black areas, which means your ability to actually, again, decrease the value of your home, your ability to repair the home, the ability to get a mortgage, so it's like all these things are confounding. One last example, people know I'm from a large family, I'm six of nine, and my mom and dad passed, but they were just great, great parents. We grew up in a house and it's actually in a video called, basically looking at RACE - The Power of an Illusion, it's in that video. But that house as Richard indicated, the picture of the house is in the video. If you see the house it's immaculate, my dad and mom were very meticulous people in that regard, and they bought the house some years ago. It was like $20,000, raised nine kids in that house. When they sold the house, the house sold, five bedrooms, three bathrooms, the house sold for $5,000.

john a. powell:

If the house had been in the suburbs, there would have been money to distribute to the nine kids. There was not. Again, the house was in immaculate shape. The location of the house was in an area that was not normally about appreciating was depreciating. So, there's these confounding mechanisms in place that you have to grapple with. I think we have to be clear that we're not just trying to make an intervention so we can make a measure of it by saying, we put so much money into home ownership for blacks. Well, that's great, but we have to look at the outcome. Did it actually produce the change we want? We had to be hardheaded about what we're trying to produce as an outcome, and instead of other areas of schools and other areas to often we say there's more money to schools. That's great.

john a. powell:

The Millicom case, the black kids are falling further behind and the goal was never just to have more money for schools. The goal was to actually do something about that opportunity and achievement gap. I think that with wealth and other things, if we really want to close the gap, we've got to better understand it on one hand and then do whatever it takes. As you know, in terms of making interventions, sometimes there are unintended consequences so we have to be willing to adapt and say that we really are trying to make a difference in terms of outcomes, not just in terms of input.

Stephen Menendian:

Thanks, john. Before I go to the next question, I want to give Marge and Richard an opportunity to add anything I may want to add.

Margery Turner:

I don't want to over-complicate this, but I think the issues that both Richard and john talked about of buying a home, but in a neighborhood that is not appreciating compared to buying a home where property values appreciate maybe faster than you expected, that is also the result, that difference is the result of segregation and discrimination, that because white people still value the separateness of white neighborhoods and because white people start out these days with more wealth, there is more price and demand pressure in white neighborhoods than in segregated black neighborhoods and other neighborhoods of color.

Margery Turner:

This is a self perpetuating cycle that we've built where the fear of integration and the demand really for a wealth hoarding, as john mentioned, continues to drive the wealth disparities that we launched through public policy in the middle of the last century. The reason I'm a little hesitant about talking about that self perpetuating cycle is that it may lead to a conclusion that there's nothing we can do about this, that we're trapped in a negative spiral, and I really resist that conclusion. I think we built this, it's our obligation to repair it, and we are capable of crafting the combination of policies, modifying them over time as they work and don't work and really put our focus on narrowing equity gaps, across domains that are driven and sustained by segregation.

Richard Rothstein:

Well, let me respond a little bit to that and add a point or two. I don't suggest in any way that there's nothing we can do about it. There's a lot we can do about it. But with the intense focus that we have these days very recently on race, we tend to forget that there are other aspects of this that are not specifically racial. The biggest aspect of it is the growing economic inequality in this country and the loss of purchasing power by working class families. That's an economic problem. It's a problem of economic inequality as you probably know, since the early 1970s, the wages of working class families of non-supervisory workers have been a smaller and smaller share of productivity gains over time, and almost all of the productivity gains this economy has made in the last 40 years have gone to the owners of capital rather than to workers.

Richard Rothstein:

That's a problem that is as powerful a way, if we can readdress it, of addressing the wealth gap as what we can do with housing, I'm not saying what we can do with housing is unimportant, but it's as powerful. We need to focus on those kinds of economic policies, as well as on racial policies in order to address it. The second point I would make is that the reason that there's so much demand, greater demand for housing in white neighborhoods and in low income segregated neighborhoods is not only because of whites' preference to live in segregated white neighborhoods. That's part of it, but it's also because segregated black neighborhoods have more industry. There's more pollution, less, as I mentioned before, less access to grocery stores that sell fresh food, less access to transportation that can get you to good jobs. These are all characteristics of segregated neighborhoods that make them less desirable places to live than white neighborhoods, quite aside from the desirability that white neighborhoods have for whites on a racial basis.

Stephen Menendian:

Thanks Richard. One of the questions that I wanted to post for you is what would you say to people who say, and Richard, you were leaning into this a bit, that the problem that we're confronting and you can define the problem however you'd like, isn't segregation and the consequences or effects of segregation, but just inequality, writ large. Do you think it's possible to solve inequality in a segregated society? Anyone.

Richard Rothstein:

Oh, I thought you were asking me. Okay.

Stephen Menendian:

No go ahead. You first.

Richard Rothstein:

Well, no, I would say it's both. Simply addressing the economic inequality will not fix this because of the inherited advantages that whites have in our economic structure over African-Americans. If, for example, john mentioned before St. Paul, that brought to mind Minneapolis that recently in attempt to address racial inequality, abolished single family zoning throughout the city. Well, there's no reason to believe that if you build triplexes in high opportunity areas that were single family zone, that will increase African-Americans access to them because they will be outbid by whites. Unless we have affirmative action in housing policies, in addition to economic reform, we're not going to be able to solve this problem. I think we need to keep in mind that it has to be both, and one of the things I began by saying earlier is because of the wonderful attention that we've had recently on racial inequality, we can make the mistake of thinking that's the only problem that we face.

Margery Turner:

I'm in total agreement, we need to do both, but I want to loop back to a point john made, which is while we do both, we need to be monitoring whether we are making progress on the racial equity gap, and if we're not we may be addressing other kinds of inequality, but it is possible we could make that kind of progress without narrowing racial equity gaps. I really think we're all in agreement do both, which is really do about 15 things at once, but with explicit attention to whether racial equity gaps across are narrowing.

john a. powell:

Yeah, of course I would agree, and I made a small, finer point. When we look at some of the economic things, the $15 an hour wage in Seattle, for example, how that rolled out. It turns out that the group that was most left behind were black women working in the service industry. I think it really is important, not, when we talk about economy, to talk about it in a disaggregated way. There are people who are situated differently and blacks and whites are situated differently and so you can improve people's economic condition, and then we usually talk about income and not wealth, and at the same time either don't address the racial disparities or even exacerbate it. I agree that we need to focus on it, but we need to focus on how race shows up in the economy over and over and over and over again.

john a. powell:

Sometimes we assume that economic intervention is race neutral. It is not and it should not be because of the disparities are not race neutral in terms of jobs people get, the experience they have, the racial and gender gap in terms of pay, all those things have to be attended to as well. Having said that we still need to actually also focus on the fact that white, I wouldn't call them work in class, because usually when we say working class implicitly, be talking about whites, whereas a large percentage of the working class, is not white, but when we're talking about white working class, we do need to attend to their stagnation that Richard talked about, but also the gap between their experience and the work of black and brown working class and women working class as well.

john a. powell:

Again, I agree with... It's a complex problem and as Marge said part of the reason why people avoid complexity is because it's hard, but also sometimes people feel like, "Well, it's too much to do, I can't do everything." We can't do everything, but we can be very smart in what we do and very strategic.

Stephen Menendian:

Two more questions then we're going to get our audience questions in here. During the presidential primaries, there was an exchange between Kamala Harris and Joe Biden about busing in Berkeley. Kamala explained that she benefited from a desegregation plan in schools in Berkeley and Joe at the time had been in government and opposed busing for desegregation. I think that to some extent was emblematic of a debate that people have had about the experience of desegregation and some who feel that it was either a failure and a bad experience, and in our report we cover some of the social science, Rucker Johnson at Berkeley has written about that. How do the three of you think about those narratives and debates? Marge.

Margery Turner:

Richard? Why don't you start this time?

Richard Rothstein:

All right. Okay. We keep on talking about complex issues, so this is another one. Many of the African-Americans who were bused to predominantly white schools during the busing era report that it was a very, very hurtful and terrible experience for them. They suffered nonstop what we now term microaggressions in the schools that they went to. They were discriminated against. We did not have two way busing to a very great extent, because although African-American were willing to participate in the integration program, by being bused busted predominantly white schools, whites used their political power to prevent the busing from bringing their children to predominantly black schools, so it was a bad experience.

Richard Rothstein:

Many of them who were interviewed later, as adults said, they would never subject their children to that experience if they had the opportunity again. However, what the social science research shows is that the children who participated in busing had much more successful adult outcomes than comparable children who didn't, difficult though, the experience was for them. If you look around today at the professional African-American middle-class that participated in busing in the 1970s, they are disproportionately successful. That's where a good part of the African-American professional successful middle-class today comes from, is from children who were bused in the 1970s. It's true, it was a very difficult experience for the people who participated, the African-American children who participated, but they received enormous benefits in terms of their experience, their life success, their adult earnings and so forth. It's a very complicated issue.

Margery Turner:

I've really been an advocate for residential integration for my entire adult life. I don't think our public policies have ever really made the effort, made the investment to advance it. But, I also have been trying to listen and understand better the perspective of African-Americans who are skeptical of, or resistant to the idea of integration.

Margery Turner:

And, as I listen and learn, one of the people I've learned the most from has been john powell. Highlighting the importance of two really profound concepts, and I hope I have absorbed them fully. One is about people's autonomy and power over their circumstances, individual and collective.

Margery Turner:

And, the second is about the sense of dignity and belonging. I think that our earlier half-hearted efforts at integration missed both those concepts. I don't think people of color had autonomy and power in those strategies. And I don't think we considered the values of dignity and belonging.

Margery Turner:

People like me, white people, who were proponents of integration were too quick to think that the neighborhoods in which we lived were unquestionably great places for everybody to live. As I think about this more, I think our next generation of policy in this space has to give more voice, more power, more choice to people of color.

Margery Turner:

And really dig into what it means to respect the dignity of people other than us, and create places where we can all feel like we belong.

john a. powell:

Thank you, I appreciate that. It is complex even as you know. We sometimes look at things at a macro level and then an individual level. At the macro level Rucker Johnson, I think has done an incredible job in his book. And I recommend his book.

john a. powell:

Richard has made reference to it. The data shows that people who have some experience, blacks are better off economically. It doesn't speak to the psychological, emotional scarring that people experience. I've talked to part of the Little Rock Nine, for example, the young people who desegregated Little Rock and, 50 years later, they're still hurting. So I think we have to attend to that. It's interesting, we've talked about busing. Busing is an example that we haven't really taken the problem seriously, because the reason people have to bus, is because they live in segregated housing.

john a. powell:

And so we're saying, we're going to keep the segregation. The parents are going to live completely separate, but you, young black child, you go have an experience and then come back. And it's the young black child, not a young white child. So we're taking all of these social problems and ills and putting them on 10 and 12 years old, two years old. And then we send them into, I think can accurately say a hostile environment. I actually was bused. And literally we fought, from the moment we got off the bus. I only remember learning one thing, I remember the fights. That's not integration, that's not even desegregation. And we, first of all, we conflate the two. And so we've never actually tried integration in a meaningful sense on a large level. There are examples in terms of schools and school districts, but we never really tried it.

john a. powell:

And it's not like... Asking people if they like busing is like asking people if they like chemotherapy, right? Busing, is really from my perspective, a weak solution to a very strong problem. And so, no, I don't like chemotherapy, but is it better than cancer? And so we need to raise the bar, redefine it. And yes so, two of the terms I want to throw out is that, in the Supreme Court case dealing with affirmative action in higher ed, the court asked the question, what is critical mass? Why is that such an important concept? And I felt like maybe the lawyers flubbed it, but the idea of critical mass is that your group is present in a large enough number. So they're not pointed out. They're not sticking out. They're not being noticed all the time. And many of these efforts to desegregate, we didn't ever achieve critical mass.

john a. powell:

So the black students, the Latino students were always aware that they did not belong, that they were at... That they were going to a white school. In my mind, if we had true integration, there would not be a white or black school. And the school wouldn't belong to the white children and the black children are there as a guest. They would fully belong as Marge said. And we haven't really tried that. We know it works, but we haven't really had public policy to support it. And the last thing I'll say is Jim Ryan, who's now the president of Virginia, but was also a law professor. He wrote an article several years ago, saying we in America have given whites a veto over integration. And so, we're willing to do it until the white's say, "No more." Whether it's, "You can't build in my backyard", "You can't..." The way we carved up much problem areas.

john a. powell:

So cities could expand at one point to make the surrounding areas part of the cities, and as cities became increasingly populated by people of color, states rewrote the rules, saying no more expansion unless you get.... So it's like, what Ryan is saying over and over again. You've given whites the right to veto any plan. And the last thing I'll say is, I think, again, it's complicated. It's not... The data shows that more and more whites actually conceptually want to live in integrated neighborhoods, but there are all these caveats, which are real. I have a 12 year old granddaughter, soon to be 12 year old granddaughter. And so, I think with my daughter, I think about schools, and you end up backing up back in to thinking about race. You think about safety. You think about parks. You think about all these other things that are oftentimes associated with race.

john a. powell:

And that's legitimate. In New Jersey, people worry that if black, white people worry that blacks moved in, the value of house will go away and end up creating an insurance policy and they didn't leave, right? I mean the whites didn't, we didn't have 'white flight.' So there are all these issues that are tied to it that are not necessarily molded by a narrow concept of racism. When race is imbued throughout these questions of, value house appreciation, schools, parks. So again, which makes the issue very complex. But busing, no one wants their kids to be bused. Although, the end mark is, in most of America, we do bus kids. You get out of urban areas and there are kids that get on the bus all the time.

john a. powell:

We lived in New York, and we lived in Brooklyn and my daughter went to school in Manhattan, but that is that she was getting a really... She went to Hunter College... Idea that she was getting something really positive. And we were exercising some agency, dignity and power in that process. It wasn't someone saying, you're going to do this and you're going to go to this white school. Anyway, so I think the story is complex. And I think most of the attack on integration is really an attack on a bad desegregation phenomenon, that we experimented with for a short period of time.

Stephen Menendian:

Richard, it looked to me like you wanted to chime back in. So I wanted to give you that...

Richard Rothstein:

No, I don't need to repeat myself. Thanks.

Stephen Menendian:

Okay. I've worked with john for nearly two decades and I learned from him something new every day. Thank you john, that was brilliantly put. So here's the last question then we're going to get to the audience. So given your decades of experience on these issues, issues of racial inequality. Richard, before you became über famous with your book on housing, you were doing a lot of work around school and education. But given all the work you've done on these issues collectively, what gives you hope today? What paths do you see forward? And, feel free to parse that question however you'd like. Let's go around. Marge, why don't you start?

Margery Turner:

So, I'm afraid my answer is going to be somewhat mundane. But, at the end of the Obama administration, I think I said more than once how optimistic I was about the new regulation they established to live up to the longstanding mandate, to affirmatively further fair housing. And I said, at that time, that if HUD could even sort of adequately implement those new rules, mediocre implementation of those new rules over the next 20 years, we might really see separate and unequal neighborhoods being dismantled. A real shift towards both integration and narrowing of disparities between neighborhoods where people of color live and people, where white people live.

Margery Turner:

So I was optimistic about that, and I've been extremely pessimistic for several years. But, I am now optimistic again, that that rule is being brought back to life. Some thinking over the last four years may lead to some refinements of it. But I really think that it is an incentive support mandate to communities to focus both on re-investing in the communities of color that have been starved of resources and opportunity, and on tearing down the barriers that exclude lower-income people and people of color from neighborhoods that are opportunity rich.

Margery Turner:

It calls on communities to tackle both those things at the same time. And again, if we can implement that, if HUD can implement that in even a mediocre level of quality, I think we could be on a 20 year path of significant progress for the country. I hope I get to live to see it.

Richard Rothstein:

Well, I am very hopeful, not confident but hopeful, but I'm not... My hope is not based on what HUD might do in the current administration, because unless there's a new civil rights movement in this country that forces HUD to do those things, it's not going to be able to get away with it. It looks good on paper, but they won't get away with it. There's no political support in this country today for even a modest implementation of the affirmatively furthering fair housing rule. What makes me hopeful? Well, it's two things. One is the process of writing and researching my book, The Color of Law made me hopeful. Because I realized that so long as we thought that the segregation this country happened by accident, happened naturally, what we call de facto segregation, it's very hard to figure out how it's going to be undone.

Richard Rothstein:

Once I came to understand, and many of my readers came to understand, that the segregation that we have in this country is primarily the result of very, very explicit public policy, it's much easier to figure out how public policy can undo it. What was done by public policy can be undone by public policy. So that's the first thing. The second thing that makes me hopeful, and again, not confident, I mentioned a minute ago, that without a new civil rights movement, we are not going to be able to give the political support to well-meaning, you'll forgive me, bureaucrats who want to implement these policies. But, we're having a more accurate and passionate discussion about race. This seminar today, and your work Stephen, show more accurate and passionate discussions about race than we ever have had before in American history, ever before in American history! And that discussion, we had 20 million people participate in black lives matter demonstrations last summer in spring.

Richard Rothstein:

And most of those were whites who were led by African-Americans. Well, we've never had that kind of white participation in racial justice demonstrations before. So there's the potential for a new civil rights movement. It needs to be organized. It needs to take much more careful and deliberate action, it needs to focus on housing. And not only on police abuse, police abuse is a critically important topic, but we need to begin to focus mass pressure, mass movement pressure on, on housing issues. But out of that passionate and accurate discussion that we're having about race in this country today, I think it's possible that a new civil rights movement will emerge. And if it does, then the things that Margery is hopeful about, may actually come to pass.

john a. powell:

Well, and Steven knows that I don't organize much around hope, but I do think that there are some possibilities, and certainly I think there's no cause for despair, or maybe some cause. But, the cause for thinking we can do something I think is even greater. And one Richard mentioned in terms of, the country's at this funny place, as we were saying there is an incredible call to sort of understand and rethink racism in America. And at the same time, an incredible call to go back to an old system of Jim Crow. So both of those things happen at the same time. And there's a lot of support, both in terms of people who are normally associated with power, and people on the streets. So it's a sense of words right. We're sort of like without much of the fire power, meaning guns and bullets. We're, relitigating the Civil War, we're relitigating the idea.

john a. powell:

I mean, there are 30% of white Americans who now strongly identify with being white as a political space. That was not true even 10 years ago. And so there's stuff that's pulling us apart. And they're, in my concern in part is, that even as we focus on racial justice in a way that allows us to come together, they would do it in a way that allows us to build bridges. And so, one of the things I liked about what Richard said is bringing the economy into the discussion and including low-income and poor whites. Not to displace the race question, and not saying low-income whites are in exactly the same position as low-income blacks, they're not, but they deserve some attention. But it's not enough to just have policy. We also have to have a really good story to actually incentivize the movement, so people can see how this relates to their daily life. So one of the things that's problematic, or difficult about these complexities is they seem abstract, and it's easy in a sense to sort of organize around the policy, that's very concrete.

john a. powell:

When I did the case on insurance, most black people didn't realize they were being redlined by an insurance company. They didn't see it. So it's hard to get people excited about something they don't see. I worked, as you know Stephen, we worked on the water case out of Detroit. And when we first started working on it, most people in Detroit didn't understand why that was an issue, until the water turned brown, until the water stopped coming. And by that time we had lost years.

john a. powell:

So part of it is help connect these problems with people's lives in a meaningful way, so that we can have that movement. But the last thing I'll say is that, I think America really is trying to, many Americans, are trying to do something different. We know here in California, for example, that inter-ethnic, interracial families are being formed at an incredibly fast rate, which was unthinkable 30 years ago. There's some projection that in a relatively short period of time, the plurality of family, new family formation in California, and by the end of the century in the country, will be mixed. That's saying something, that's saying that kind of personal animus is not there, at least for some Americans. That's something to build on. We haven't told a story about that.

john a. powell:

And one of the things you worked on Stephen, is that while people are skeptical about the federal government, there are cities all across the country that are rezoning. That are getting rid of zoning or exclusively single-family housing. And part of the reason they're doing that is to try to address racial justice. I agree with Richard, by itself it won't produce that, but then at least there's the goal. And I think we should be helping them say, okay, you need to do this, this, this, this, if you're going to do that, and then you need to follow the data and make interventions. So people are trying. I just think they're not... Because the problem is complex, they want a single answer and there's not a single answer, but I think there's an openness. And I think we should help in terms of helping people take that complexity, and not being paralyzed by it, and figuring out strategies to move forward.

Stephen Menendian:

Thanks, john. I think we actually have a question about zoning from the audience. So Holly says, can you please address zoning changing from single-family to multi-unit zoning? Many believe it is not enough to reduce housing costs without specific requirements for affordability. Thoughts?

john a. powell: