Download this report here. Read the press release here.

In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed a bipartisan commission and charged it with analyzing the underlying causes and conditions that led to over 150 race-related riots during that summer. The Kerner Commission sent field teams to cities that had experienced race-related uprisings to interview residents and conduct detailed demographic and sociological analyses. In a more than 600-page report, the Commission constructed 10 “profiles of disorder” that examined each city’s media and police response to the unrest, and the historical conditions that created neighborhoods of racially concentrated poverty.

Many of the important Kerner Commission recommendations to address systematic inequality identified in the 1960s were subsequently ignored due to the cost of the Vietnam War, which absorbed federal discretionary funds and sapped the Johnson administration’s political capital. A backlash to the civil rights movement also made substantial policy reforms politically unattainable. Although in some respects racial equality has improved in the intervening years, in other respects today’s Black citizens remain sharply disadvantaged in the criminal justice system, as well as in neighborhood resources, employment, and education, in ways that seem barely distinguishable from those of 1968.

In the spring of 2018 the Othering & Belonging Institute (then known as the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society), in partnership with the Economic Policy Institute and the Johns Hopkins University’s 21st Century Cities Initiative, hosted “Race and Inequality in America: The Kerner Commission at 50,” a national conference to review and commemorate the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, whose ominous warning stunned the nation: “Our Nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white–separate and unequal.”

Watch a video recap of the conference above

The conference examined the history, legacy, and contemporary significance of the Kerner Commission. More than 30 experts in the realm of housing, education, health, and criminal justice convened in Berkeley to investigate why so few of the Kerner Commission’s recommendations were implemented, and how we might envision a similar and equally bold policy agenda for this moment.

This report memorializes key findings of the conference, focusing on two issues that the Kerner Commission addressed—policing and housing—to gauge what progress we have made toward advancing the recommendations made by the Commission and to examine where we have fallen short.

Introduction

In the last five years nearly 100 unarmed African Americans have been killed by police.1 Too often, there was no apparent plausible justification, including in the widely publicized cases of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Walter Scott in North Charleston, Freddie Gray in Baltimore, and Eric Garner in New York. In other cases, although the victims were lightly armed (sometimes with a pocketknife, or even a toy gun), police action was also excessive.

In the aftermath of many of these deaths, protests led by enraged residents, predominantly African American, arose and grew into a movement known as Black Lives Matter (BLM). These uprisings in Ferguson, North Charleston, Baltimore, and New York reflected not only outrage over the individual killings by police, but also decades of discriminatory treatment throughout the criminal justice system, as well as in housing, employment, and education.

Profiles of Racial Disorder Today

BLM traces its beginnings to 2013 when George Zimmerman was acquitted after fatally shooting Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old unarmed Black teenager in Sanford, Florida. Founded by activists Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, BLM began as a hashtag on social media but quickly evolved into a nationally recognized movement in 2014 after the killings of Eric Garner and Michael Brown.2

Garner, an unarmed man selling untaxed single cigarettes on a street corner in Staten Island, New York, was killed after a police officer tackled him and pinned him down as Garner choked and gasped, “I can’t breathe.”3 Less than a month later, Brown, an 18-year-old college bound African American was fatally shot multiple times by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, after a confrontation. Robert McCulloch, St. Louis County's prosecuting attorney who declined prosecuting police officer Darren Wilson, blamed the 24-hour news cycle and its “insatiable appetite” for spreading rumors and inciting protests.4

The deaths of Brown and Garner prompted thousands of individuals to take to the streets in protests across the country. Notably, in Ferguson the police department responded to all demonstrations, including peaceful rallies, with force and the use of military grade equipment such as tear gas, armored vehicles, sound cannons, and rubber bullets.5 More than 400 people were arrested in Ferguson, and 150 people were taken into custody on “failure to disperse” charges.6

In the following months, BLM protests also responded to other apparently unjustified police killings of African American men. In North Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, Walter Scott, a 50-year-old unarmed African American US Coast Guard veteran was shot eight times as he ran away from a police officer who had stopped him for a broken taillight.7 Two weeks later in Baltimore, Maryland, Freddie Gray died from injuries he sustained, including a broken spine, when he was tackled, put in a police van, and given a “rough ride.”8

Subsequently, the Baltimore State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby revealed that the ostensible charge against Gray, that he had an illegal switchblade, was false and that at the time of his arrest, Gray was legally in possession of a pocketknife.9 Again, intense rallies organized by BLM erupted in reaction to Scott and Gray’s deaths. In Baltimore, the reaction was intensified by the lack of information that police and local government provided about the circumstances surrounding Gray’s death. While there were large nonviolent demonstrations in Baltimore, in some gatherings there were reports of individuals smashing and burning vehicles, looting stores, and throwing bricks and rocks at officers. Police arrested a number of protesters, including members of the press, and beat at least one protester.10 All six officers involved were either acquitted or had the charges against them dropped.11

Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were at the center of the next wave of national BLM protests. In July 2016 Sterling, selling homemade CDs outside a convenience store in Baton Rouge, was shot and killed at close range by a police officer.12 Just one day later in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, a suburb of St. Paul, Castile was pulled over on a traffic stop with his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter. Castile informed the officer he was legally in possession of a gun and told him he was not reaching for it, but the officer shot him seven times.13 Castille’s girlfriend, who filmed the incident on her cell phone, said Castille had been reaching for his identification at the time he was shot, but the officer involved said that he had reason to fear Castille was reaching for the gun in the car.14

These incidents spurred a wave of protests—some violent—in dozens of cities across the country in July 2016,15 leading to the arrest of nearly 200 demonstrators.16 The widespread sense of injustice precipitated national anthem protests led by then-NFL player Colin Kaepernick to take a knee as the anthem played to express solidarity with the BLM movement.17 Sporadic protests continued through the rest of the year.18

Recent Police Killings Are the Catalyst for, rather than the Root Cause of, Black Lives Matter Uprisings

Investigations conducted by the US Department of Justice (DOJ), the Ferguson Commission (created through an executive order issued by the governor of Missouri in the aftermath of Michael Brown's killing), and others into the protests, and the police practices that precipitated them, have attributed BLM uprisings to the continued pervasive discrimination Black communities face throughout the criminal justice system, as well as in employment, education, and housing.19

In recent years, only a handful of police officers involved in seemingly unjustified police killings have been criminally charged.20 At the same time, evidence that these killings are part of broader schemes of racial targeting have been brought to light. For example, in 2015 the DOJ issued a scathing report about Ferguson, stating that the city’s law enforcement practices were “shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs.”21 Specifically, the DOJ found that Ferguson officials had put pressure on the police and the city manager to ramp up ticket writing and court fees to garner money for the city.22 As a result, the largely white Ferguson police force targeted African American neighborhoods, viewing these individuals as “potential offenders and sources of revenue” rather than constituents in need of protection.23

The DOJ’s 2016 investigation of Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray shed light on another city’s discriminatory practices. The report found that the Baltimore Police Department’s (BPD) legacy of zero tolerance enforcement led to an unconstitutional pattern of stops, searches, and arrests, which disproportionally impacted African American residents.24 BPD made 44 percent of its pedestrian stops in two small, predominantly African American districts that contained 11 percent of the city’s population, resulting in hundreds of individuals—nearly all of them African American—being stopped from 2010 to 2015. Seven Black men were stopped over 30 times each during this period.25 The DOJ also found that BPD routinely used excessive force, failed to adequately train police, and did not hold police accountable for serious misconduct.26 The DOJ noted that this behavior was particularly problematic in a city with a long legacy of economic and housing discrimination, causing over 100,000 African American Baltimore residents to live in poverty in the present day.

Today’s Racial Injustice Is a Continuation of the “Profiles of Disorder” Analyzed in the 1968 Kerner Commission Report

Public unrest, sometimes violent, precipitated by police killings is not a recent phenomenon. In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed a bipartisan commission and charged it with analyzing the underlying causes and conditions that led to over 150 race-related riots during that summer. Headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, with Mayor John V. Lindsay of New York as vice chairman, the Commission issued its report on February 29, 1968.

The Kerner Commission sent field teams to cities that had experienced race-related uprisings to interview residents and conduct detailed demographic and sociological analyses. In a more than 600-page report, the Commission constructed 10 “profiles of disorder” that examined each city’s media and police response to the unrest, and the historical conditions that created neighborhoods of racially concentrated poverty. The Commission’s final report was the most extensive assessment of racial inequality and the most robust policy agenda seeking to address these issues that any US government entity has released to date.27

Many of the Kerner Commission’s profiles bear striking resemblance to accounts of recent cases of police brutality. Consider, for example, the July 1967 killing of Martin Chambers, an unarmed Black teenager in Tampa.28 Police chased after Chambers, who was suspected of robbing a camera equipment store, and trapped him at a high fence. At that point, Chambers put his hands up to surrender, but was fatally shot by an officer, according to eyewitness reports. Later, the officer claimed, and the Florida state attorney agreed, that the shooting was necessary to prevent a felon from fleeing police apprehension.29 Chambers’s killing set off three days of intense protests that involved violence, looting, and setting property on fire. Approximately 1,000 law enforcement agents were called to assist the local police, including National Guardsmen and Highway Patrol troopers.30

In a manner similar to both the Ferguson and Baltimore DOJ reports, the Kerner Commission found that the “precipitating event”—Chambers’ death—was merely the latest incident in a litany of grievances in Tampa, ranging from Black unemployment to the lack of educational opportunities. In a city where African Americans comprised 20 percent of the population in 1967, no African Americans had ever served on the city council, school board, fire department, or in a high-ranking position on the police force.31 Out of every 10 Black homes, six were deemed uninhabitable.32 A majority of Black children had not attained an eighth-grade education.33 More than half the city’s Black families had incomes of less than $3,000 a year (just over $22,000 in 2017 dollars).34

Many of the important Kerner Commission recommendations to address systematic inequality identified in the 1960s were subsequently ignored due to the cost of the Vietnam War, which absorbed federal discretionary funds and sapped the Johnson administration’s political capital. A backlash to the civil rights movement also made substantial policy reforms politically unattainable. Although in some respects racial equality has improved in the intervening years, in other respects today’s Black citizens remain sharply disadvantaged in the criminal justice system, as well as in neighborhood resources, employment, and education, in ways that seem barely distinguishable from those of 1968.

Kerner at 50: The Road Not Taken

In the spring of 2018 UC Berkeley’s Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, in partnership with the Economic Policy Institute and the Johns Hopkins University’s 21st Century Cities Initiative, hosted “Race and Inequality in America: The Kerner Commission at 50,” a national conference to review and commemorate the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, whose ominous warning stunned the nation: “Our Nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white–separate and unequal.”35

The conference examined the history, legacy, and contemporary significance of the Kerner Commission. More than 30 experts in the realm of housing, education, health, and criminal justice convened in Berkeley to investigate why so few of the Kerner Commission’s recommendations were implemented, and how we might envision a similar and equally bold policy agenda for this moment.

This report memorializes key findings of the conference, focusing on two issues that the Kerner Commission addressed—policing and housing—to gauge what progress we have made toward advancing the recommendations made by the Commission and to examine where we have fallen short.

Part I: Then and Now

Amid Some Improvements, Inequality Persists in American Systems

We have mostly fulfilled the Kerner Commission warning that without dramatic reform, the nation would become “two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” Since the 1960s, in important respects, the lives of African Americans have improved. In many respects, they have remained unchanged. And in some respects, they have deteriorated. In almost all respects, unacceptable levels of racial inequality have persisted.

The Black Middle Class

Perhaps the most important area of improvement has been the growth of the Black middle class, and its significant incorporation into the mainstream of American life. The most obvious symbol of this was the election and reelection of a Black president. The most obvious symbol of its limitations was the reaction in the subsequent election of a president whose campaign and subsequent actions emboldened white supremacists.36

In 1966, shortly before the Kerner Commission began its deliberations, one of us participated in a study of policymaking in Chicago’s corporate sector. We identified 4,000 such corporate leadership positions: not a single one was held by an African American. The only executives who were African American worked at insurance firms or neighborhood banks for which the segregated Black community provided a customer base.37 Today few, if any, mainstream corporations could function without racially diverse management.

This improvement has relied upon the growth of the well-educated African American population. In 1980, only 10 percent of young African American adults old enough to have completed college did so. Subsequently, this share grew steadily and by 2017, 23 percent had college degrees, an increase of 128 percent.

Although the growth in the share of African Americans who are college-educated represents progress, racial inequality in higher educational attainment has also increased. While the share of young adult. African Americans who had completed college grew by 128 percent, the growth for whites was 143 percent (from 17 to 42 percent of young adults). As a result, the college graduation gap has grown, not diminished. In 1980, for every young adult African American who had completed college, seven whites had done so. In 2017, for every young adult African American who had completed college, eight whites had done so.38

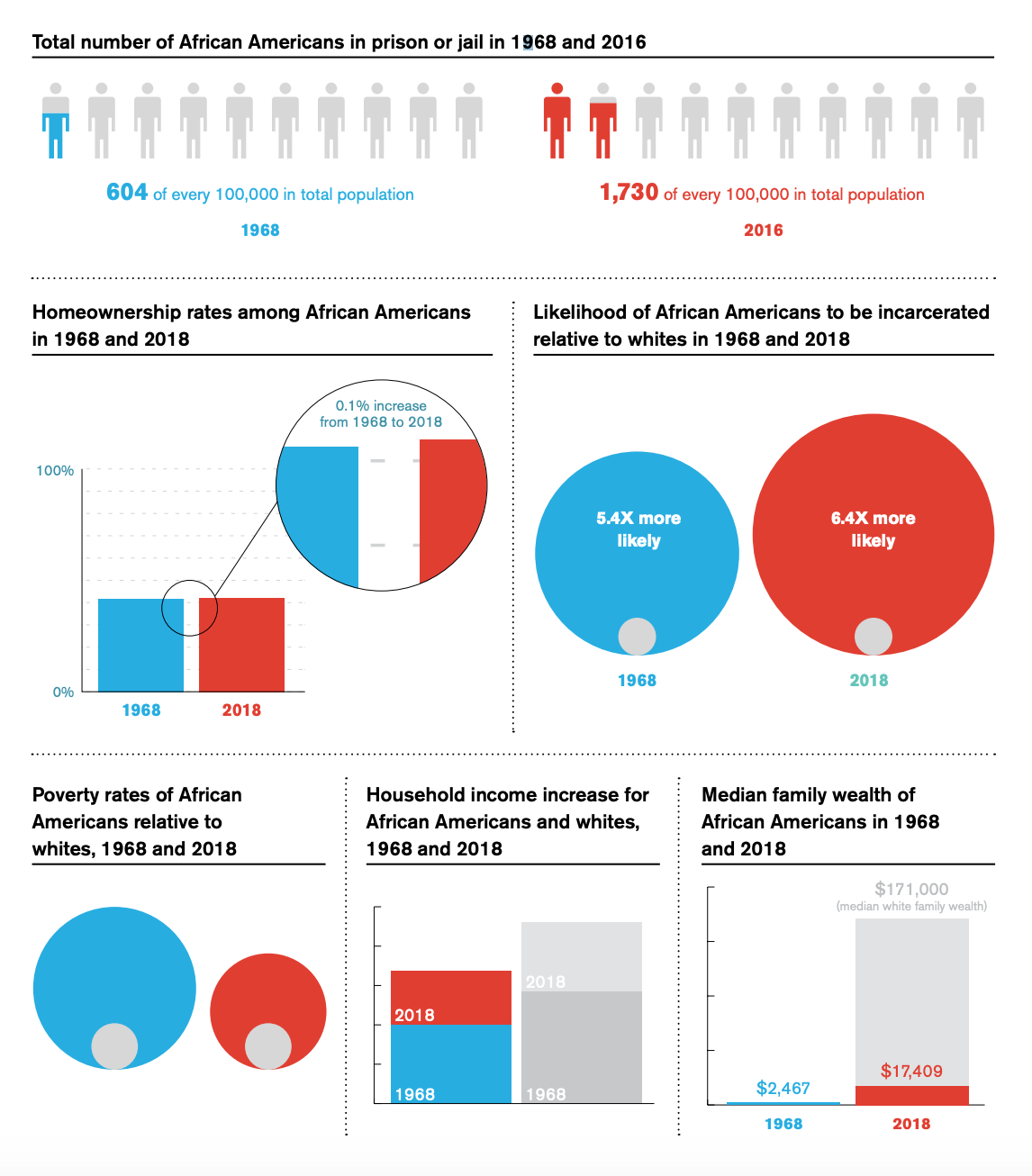

Mass Incarceration

In 1968, approximately 600 African Americans were incarcerated per 100,000 African Americans. In 2016, the share of African Americans who were incarcerated had jumped to over 1,700 per 100,000. The incarceration rate for whites had also increased by 2016, but not by as much as the rate for African Americans. In 1968, the African American rate of imprisonment was about five times the rate of whites. In 2016, the African American rate was six times the rate of whites.

Economic Conditions

In 1968, the African American unemployment rate was twice that of the white rate. This was unchanged in 2017: the African American unemployment rate was still twice that of the white rate.39

For those who were working, the real average hourly wage of African American production and non-supervisory workers increased by 31 percent from 1968 to 2016, much less than the growth of real per capita national income. Yet the real average hourly wage of white production and non supervisory workers increased even less—only by 13 percent. Thus, African American workers gained relative to white workers. African Americans’ average hourly wages were 83 percent of white average hourly wages in 2016, up from 71 percent in 1968.40

Likewise, African American median household income grew faster than white household income, but a racial gap remains. From 1968 to 2016, African American median household income increased by 43 percent, while white median household income increased by 37 percent. Still, in 2016, African American median household income was only 62 percent of white median household income.41

The racial wealth gap is even greater. In 1968, African American median household wealth was only 5 percent of white median household wealth. From then until 2016, African American median household wealth grew, and by 2016 was seven times the 1968 figure. During the same 1968 to 2016 span, white median household wealth tripled. By 2016, African American median household wealth was still only 10 percent of white median family wealth.42

Most American families accrue wealth from owning homes that appreciate more rapidly than overall inflation, generating equity. The African American home ownership rate of 41 percent was unchanged from 1968 to 2015, while the white rate grew from 66 percent to 71 percent. Yet the wealth difference is not solely attributable to the difference in homeownership rates. Rather, it is also that whites typically own homes in white segregated neighborhoods where values appreciate more rapidly than in the segregated neighborhoods where African Americans typically own homes.43

Racial Segregation

- School Segregation

- African American students are no less segregated in elementary and secondary schools today than they were in 1968. In the year of the Kerner Commission Report, only 23 percent of Black students attended schools that were majority white. That percentage increased to a high of 44 percent in 1988, after which it began to decline. By 2011, it was again the case that only 23 percent of Black students attended schools that were majority white.44

- Neighborhood Segregation

- The exposure of African Americans to whites in neighborhoods has remained almost unchanged since 1968. Although fewer African Americans now reside in all or mostly Black neighborhoods than in 1968, this is mostly because more members of other minority groups, frequently low-income families—often Hispanics and Asians—have located in predominantly Black neighborhoods. In 1970, the typical African American resident of a metropolitan area lived in a neighborhood that was 32 percent white. By 1990, African Americans’ exposure to whites increased, and the typical African American lived in a neighborhood that was 42 percent white. Yet since then, African Americans’ exposure to whites declined, and by 2010, the typical African American lived in a neighborhood that was only 35 percent white.45

Health

- Life Expectancy

- African American men born in 1968 had an average life expectancy of 60 years. Those born in 2014 had an average life expectancy of 73 years, a gain of 13 years. This is a substantial improvement and it narrowed the Black-white life expectancy gap for men. For white men, those born in 1968 had an average life expectancy of 68 years, and those born in 2014 had an average life expectancy of 77 years, a gain of nine years. Thus, African American men born in 2014 could expect to have lives that were four years shorter than those of white men born in the same year. This is half the racial life-expectancy gap of eight years for men born in 1968.46

- For women, the change was similar. African American women born in 1968 had an average life expectancy of 68 years. Those born in 2014 had an average life expectancy of 79 years, a gain of 11 years. This is also a substantial improvement and it narrowed the Black-white life expectancy gap for women. For white women, those born in 1968 had an average life expectancy of 75 years, and those born in 2014 had an average life expectancy of 81 years, a gain of six years. Thus, African American women born in 2014 could expect to have lives that were two years shorter than those of white women born in the same year. This is less than one-third of the racial life-expectancy gap of seven years for women born in 1968.

- Infant Mortality

- Specific health outcomes of African Americans have improved, and contributed to the narrowed gap in life expectancy. In 1968, the African American infant mortality rate was 4 percent (36 infant deaths per 1,000 live births). By 2012, it had fallen to 1 percent (11.3 per thousand). For whites, the 1968 rate was 2 percent (20 per thousand), falling to half of one percent (5.1 per thousand) in 2012. Thus, despite substantial improvement for both races, the African American infant mortality rate remained approximately twice that of the white rate.47

Basic Educational Attainment

Above, we described the increase from 1970 to 2017 in the share of young African American adults who had bachelor’s degrees. There was similar growth in the share who had completed secondary education, either by graduating from high school or by earning a GED (general educational development) certificate. From 1970 to 2017, this share increased by more than half, from 58 percent to 92 percent.48 This growth narrowed the gap between the secondary school completion rates of white and Black students. The share of young white adults with a complete secondary education grew during this period from 78 percent to 96 percent. Thus, by 2017, the Black-white gap in secondary completion rates had nearly disappeared (92 percent to 96 percent). However, while this is good news with regard to equality in literacy and quantitative skills necessary for democratic participation, the labor market value of a secondary school credential-only had diminished by 2017.

Part II: Criminal Justice

Criminal Justice System and Police Reform

Police misconduct, disrespect, and violence were among the most serious complaints surfaced by the Kerner Commission’s field investigations. The Commission listed “police practices” as the issue, above all, that elicited the most intense grievance among communities affected by disorder. Not surprisingly, the Commission made reforming police behavior and conduct a priority, and dedicated an entire chapter to recommendations under the header “police and the community.”

Critically, however, the Kerner Commission found that the issue of police misconduct was recognized to be a “trigger” or “inciting incident” but was not the truer, deeper cause of unrest. Rather, instances of police abuse were the most salient and visible aspect of a larger system of inequity. At the same time that police violence has become an important part of today’s national conversation on race, equally important is the role of the criminal justice system and the rise of mass incarceration in seeding and perpetuating racial inequality. Therefore, this section will examine the Kerner Commission’s police reform recommendations in light of a larger set of issues pertaining to criminal justice reform and the broader criminal justice system in 2019.

Kerner Commission Recommendations:

The Kerner Commission advanced more than two dozen specific recommendations relating to policing reform, but organized its recommendations under five “basic problem areas”: The need for change in police operations in ghettos, to ensure proper conduct by individual officers and to eliminate abrasive practices.*

- The need for more adequate police protections of ghetto residents, to eliminate the high sense of insecurity to person and property.

- The need for effective mechanisms for resolving citizen grievances against the police.

- The need for policy guidelines to assist police in areas where police conduct can create tension.

- The need to develop community support for law enforcement.

Although progress has been made in each area, all five areas continue to have significant and enduring problems. Below we examine each Kerner Commission recommendation both individually and in the context of today’s larger questions about criminal justice reform.

Police Conduct and Patrol Practices

Abuse of community members in neighborhoods of racially-concentrated poverty was the most serious grievance recounted by the Kerner Commission, but it is one that has seen the least progress in the intervening years. In addressing this problem, the Kerner Commission recommended the curtailment of police misconduct, including “indiscriminate stops and searches,” physical abuse, harassment, and “contemptuous and degrading verbal abuse.”

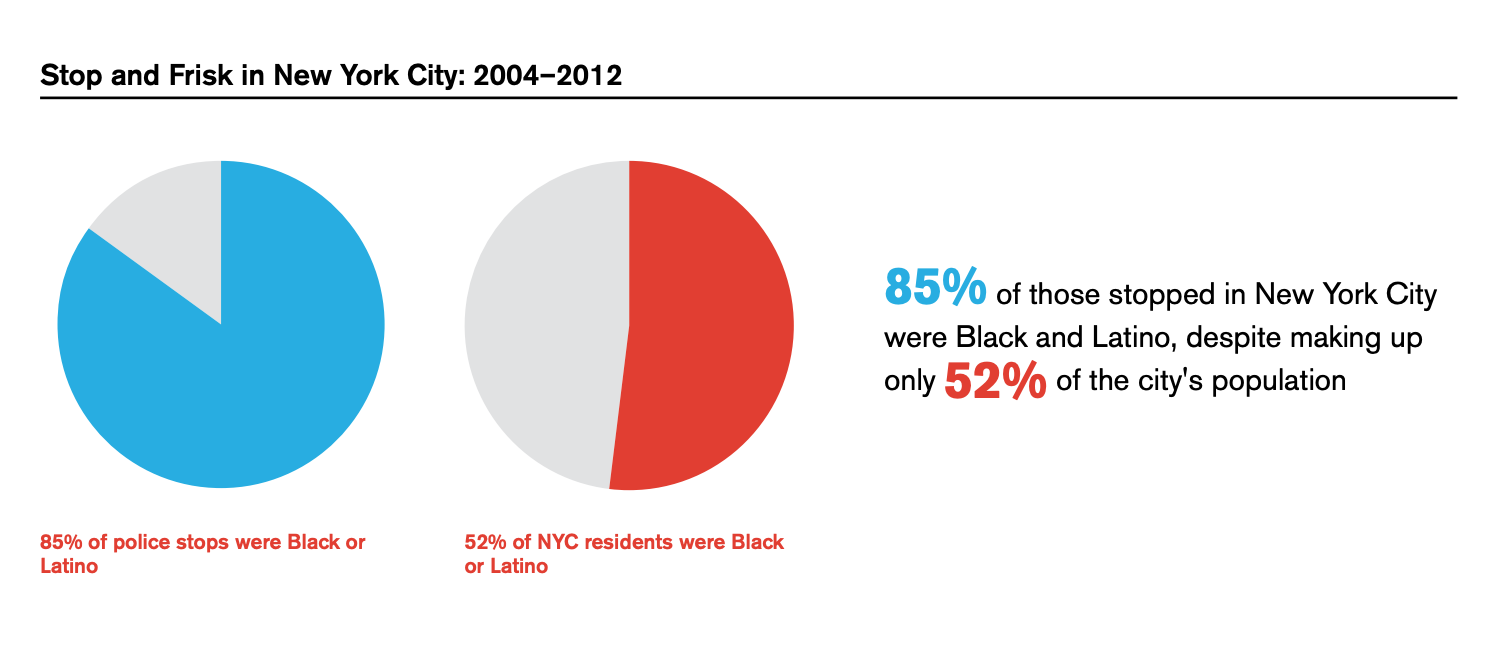

Unfortunately, “broken windows” policing, a philosophy that urged police to target minor crimes with the goal of creating a more orderly community atmosphere that would discourage more serious crimes was ascendant since the 1970s.49 This policing philosophy led to more aggressive misconduct and more pervasive “indiscriminate stops and searches,” known in some places as “stop and frisk.” This tactic was embraced by cities with large Black populations nationwide, including Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Newark, Chicago, Baltimore, and New York City.50

Although many of these cities are not required to collect data from “stop and frisk” incidents, a lawsuit revealed that from 2004–2012 approximately 85 percent of those stopped in New York City were Black or Latino, even though those two groups made up only 52 percent of the city’s population.51 New York City’s “stop and frisk” policy was halted and reformed in 2013 when a federal judge held that the New York City Police Department (NYPD) had engaged in a pattern and practice of racial profiling in violation of the Constitution.52 But because the City of New York settled the case, it is uncertain whether such practices would have been held unconstitutional upon appeal.53 Further, numerous cities continue to engage in “stop and frisk” and as recently as October 2018, the Trump administration praised the tactic, and suggested that Chicago and other cities return to aggressive policing to combat crime.54

The Kerner Commission recognized that “motorized” patrol practices changed the police-civilian dynamic from earlier generations, and noted that the motorized police patrolman “comes to see the city through the windshield and hear about it over a police radio. To him the area increasingly comes to consist only of lawbreakers. To the ghetto resident, the policeman comes increasingly to be only an enforcer.”55

Motorized patrol practices have hardly abated in the years since the Kerner Report. Although efforts to promote “community policing” have emphasized “foot patrol” over motorized patrol, these efforts have not been broadly adopted. In fact, the opposite has occurred.56 By the late 1980s, the DOJ recognized that motorized patrol was the centerpiece of contemporary policing practices.57

Further, foot patrol has been unpopular with local police who viewed it as too informal and ineffective in responding quickly to crises.58 However, more recent studies have affirmed the value of foot patrol, including a major study by the Police Foundation in 2016 finding that this type of policing facilitates relationship building in communities and enhances the problem-solving capability of law enforcement.59 Although it is manpower intensive, foot patrol may be a key to community policing models.

The Kerner Commission also recommended that police departments develop rules prohibiting police misconduct and “vigorously enforce” those rules and standards. While most police departments have now developed rules governing conduct, police officers are accorded broad discretion in determining the scope of appropriate behavior. Much of the lack of police accountability stems from qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that protects police from suit under federal statute 42 US Code § 1983.60 When a police officer uses excessive force, or conducts an unlawful arrest or search, that officer can escape liability if she proves she reasonably believed her conduct was lawful, even if it was not.61 Further, even if the jury finds the officer liable for unlawful conduct, federal law does not require the police department to pay a reward to the victim.62 The reasonableness standard provides a wider scope of discretion than a higher standard might, and undermines comprehensive police department rules governing police conduct.63

In addition to stricter standards governing police conduct on the use of force, training police to de-escalate conflict also provides an important check on police misconduct. De-escalation training teaches police to identify and communicate with individuals who are experiencing mental and emotional crises in order to defuse dangerous situations.64 Only eight states require all officers to undergo this type of training, while the 34 states that have left police training decisions to local agencies have adopted no or very little de-escalation requirements.65 For example, as of February 2017, Georgia requires only one hour of de-escalation training per year.66 Local police departments cite lack of staff and resources and a prevailing belief that training is unnecessary as reasons for not adopting such programs. Statewide mandates should be adopted to ensure all police are equally and fully equipped to use the least amount of force against communities as possible.67

Police Protection

The Kerner Commission identified a lack of community protection and police resources in racially concentrated areas of poverty as contributing to a feeling of insecurity among residents. The Commission warned that “enforcement emphasis should be given to crimes that threaten life and property. Stress on social gambling or loitering when more serious crimes are neglected, not only diverts manpower but fosters distrust and tension in the ghetto community.” Although increased state and federal funds have been directed to local police departments in these communities, these resources have been used to criminalize rather than protect communities through “broken windows” policing as was discussed earlier.

The focus of police resources on targeting low-level crimes has had grave implications for victims of color. A study conducted from 2008 to 2018 found that in major cities “an arrest was made in 63 percent of the killings of white victims, compared with 48 percent of the killings of Latino victims and 46 percent of the killings of black victims. Almost all of the low-arrest zones are home primarily to low-income black residents.”68 In Stockton, California, 40 percent of Black killings result in an arrest, while more than 60 percent of white killings result in an arrest.69 In Miami, police only solve less than a third of killings of Black victims, whereas cases where a white person has been killed result in arrests at least 50 percent of the time.70 Some critics speculate that the lack of accountability or ability of police to solve these crimes contributes to, rather than ameliorates, violence in these neighborhoods.

Grievance Mechanisms

One of the main concerns expressed by the Kerner Commission was the “almost total lack of effective channels for redress of complaints against police conduct.”71 Police officers, it was felt, behaved with impunity or some measure of indifference because of a well-founded belief that they had little risk of punishment, even for violation of procedure or protocol. In fact, it noted that a 1967 Civil Rights Commission found that complainants of police misconduct were frequently victims of retaliation. The Commission presented five recommendations to improve grievance mechanisms:

- Make filing complaints easier and do not require that individuals file these complaints at a central office.

- Have a specialized, separate agency with adequate funds and staff handle complaints.

- Ensure that the complaint procedure has a builtin conciliation process.

- Allow the complaining party to participate in the investigation and process.

- To change policy, require that information regarding the resolution of complaints is forwarded to the departmental units which develop department policies and procedures and to training units responsible for instructing officers on these policies and procedures.

Although the particulars vary from city to city, most large, metropolitan police departments now permit complaints to be filed in the manner recommended by the Kerner Commission. The advent of communications technology has greatly aided the process and possibilities for citizens to file grievances without needing to travel to a central office location during work hours. For example, the BPD, which was subject to a DOJ investigation following the death of Freddie Gray, allows citizens to file complaints by email, phone, or mail, in addition to in-person filing.72

There are very few instances, however, of a police complaint procedure being handled by a separate, specialized agency, per the Kerner Commission’s recommendation. Instead, most complaints are handled by “internal affairs” offices, whose processes are as opaque as they are vague. There are no national or state standards governing the internal affairs process.73 Nor is there good research on the operations or standards of internal affairs units, according to experts.74 According to one research scientist who studied police policies, as of 2015 “[there is] really no general practice, other than the fact that agencies tend to have an internal affairs unit and they tend to investigate officers for misconduct.”75

In some cases, however, internal affairs review boards work alongside civilian review boards, which seeks to further police accountability by allowing non police community members to provide input and police oversight.76 In most cases, the civilian review board does not have investigatory authority, but supports or acts in concert with investigators. In some cases, however, review boards are more independent. The NYPD, for example, has a civilian review board that is an independent, separate agency, which also allows complainants to connect with officers involved in their complaint.77 Baltimore also has an independent civilian review board made up of citizens from each of the districts in the city and are appointed by the mayor.78 In 2015 Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel recommended the establishment of a civilian-led review board to assist in the oversight of the city’s police department, but the Chicago City Council is still negotiating the structure and role of this board.79

Still, many cities lack effective police complaint procedures. Following the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, a DOJ investigation revealed a system in which officers dissuaded citizens from lodging complaints, retaliated against those who did, and repeatedly failed to investigate allegations of misconduct. The DOJ found that all of these actions served to condone officer misconduct and fuel community distrust.80

Further, a study of rates of punishment following complaints in large state and local law enforcement agencies found that only roughly 5–8 percent of such complaints were found to be eligible for disciplinary action.81 In New Orleans, that rate was 5.5 percent. In Newark, it was under 5 percent.82 While it is unclear what percentage of complaints actually resulted in discipline, these rates may understate the problem, considering that many police misconduct incidents do not result in complaints being filed in the first place.83

Policy Guidelines

Another area of recommendations advanced by the Kerner Commission was the creation of systematic policy guidelines for police, which regulate and govern police action and interventions in a range of scenarios. Although the Commission recognized the need for discretion and good judgment, it nonetheless felt that contacts between the police and citizens should be based upon carefully designed and written departmental policies. This responsibility, the Commission felt, was not simply the province of police departments, but local civilian authorities.

In intervening years most police departments have created policy guidelines that specify the range of appropriate or recommended conduct for officers. For example, departments now have detailed guidelines for the use of force, including each weapon.84 Police department manuals not only cover use of force, but also arrests, care and transport of arrestees, and vehicle and patrol operations.85 The level of detail and specificity provided in these manuals varies widely, as does the degree of prescriptiveness.86 Some guidelines are merely laudatory while others are framed as requirements.

Moreover, the main problem is not that there is a lack of clear guidance, but that the standards or guidelines themselves are too lax or discretionary. Exponents of greater police accountability have pushed for stricter guidelines on the use of force. The prevailing national standard permits the use of force where there is a “reasonable cause,” as set out by the United States Supreme Court. State and local efforts to raise standards on the use of force by police above this standard generally face intense opposition from departments and police unions.

Following the shooting death of Stephon Clark in Sacramento, a bill was introduced in the California state legislature that would prohibit the use of deadly force except “where it is necessary to prevent imminent and serious bodily injury or death to the officer or another person.”87 Seattle implemented a similar standard, restricting the use of deadly force to situations in which an “officer fears an imminent threat of injury or death.” Since implementing this standard, the Seattle Police Department has had fewer incidents of civilians killed by police officers.88

Community Support

The Kerner Commission also felt that police departments must take affirmative steps to gain the support of the communities they serve. It found that the breakdown of communication and trust undermined the effectiveness of the police as an institution. Therefore, it developed a number of recommendations designed to improve community relations.

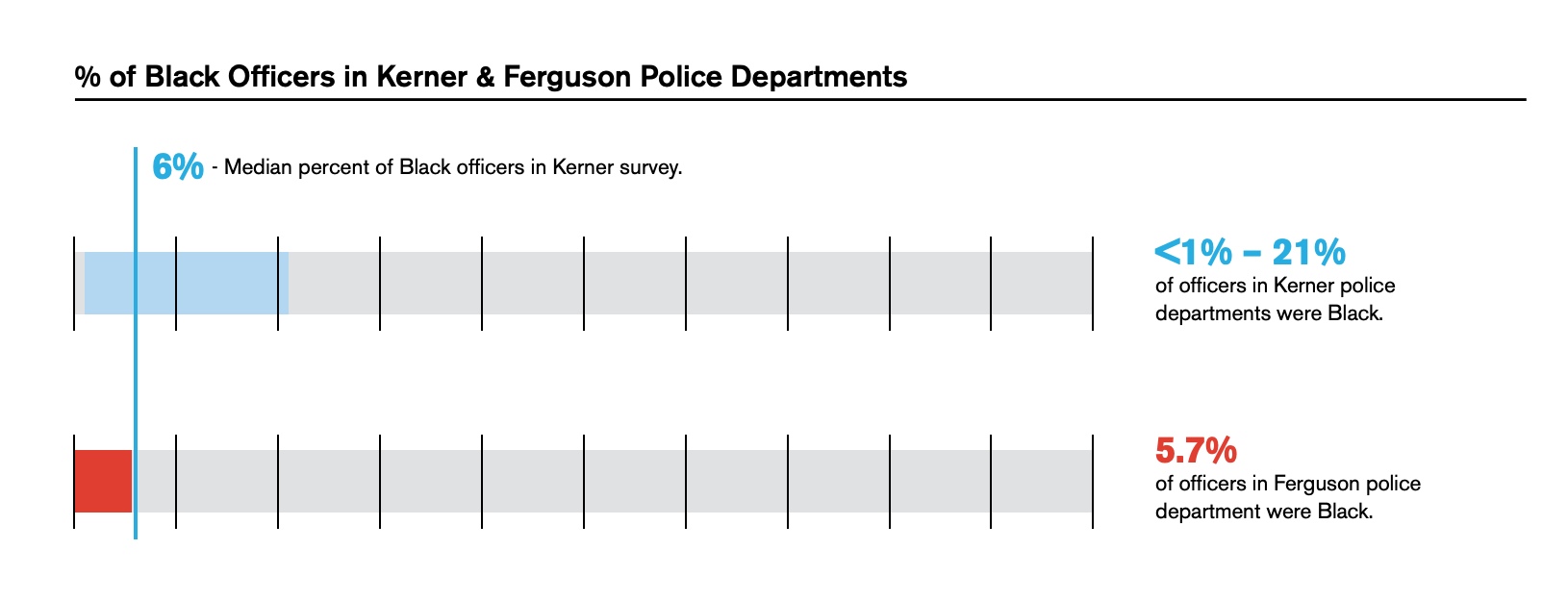

First, it recommended that police departments make a concerted effort to hire more Black officers. Without supposing that this would be a cure-all, the Commission noted that in the 28 departments it surveyed, Black officers ranged from less than 1 percent to 21 percent of all officers, and that the median was 6 percent.89 Moreover, in no case was the proportion equal to the representation in the community. This disparity, it found, was more acute among supervisory personnel.

Although most major police departments today are far more diverse than those surveyed by the Kerner Commission, they still do not fully reflect the communities they serve, especially in senior leadership. According to a 2013 study of police departments serving communities with more than 100,000 residents, racial minorities are underrepresented on average by 25 percent.90 Most infamously, the Ferguson Police Department at the time of Michael Brown’s death and the subsequent uprisings consisted of 50 white officers and three Black officers in a city that was 67 percent Black in 2014.91

While the under representation of Black officers remains acute, neither we nor the Kerner Commission believe diversifying rank-and-file or police leadership would solve the problems that undermine trust and community support, including the frequency or brutality of violence. However, greater community representation brings local knowledge into these departments while opening the doors of opportunity for officers that have been traditionally excluded.

Second, the Commission recommended the use of community policing practices to improve communications with civilians and better allow police to perform their community service functions. The Commission specifically recommended that the federal government launch programs to establish community service officers or aides in communities with more than 50,000 people. The Commission also recommended that departments strengthen community relations programs, which have little in-house support and were often little more than “public relations programs,” designed to bolster the departments’ images.

In 2015 the Obama administration established a task force on “21st Century Policing” that advanced recommendations along these lines and highlighted community policing as one of the “pillars” of reform.92 Following this announcement, cities such as Richmond, California, made substantial progress in both reducing crime and improving community relations by implementing a number of community policing efforts, including long-term patrol assignments to build trust, improved department transparency, more frequent use of foot patrol, and greater accountability for bad police behavior.93

Cincinnati, the site of another uprising in 2001 following a police encounter, was lauded by the Obama task force for its efforts. The city’s community policing effort was focused on “problem solving” rather than control, and saw a dramatic (69 percent) reduction in police use of force.94 Whether such programs can be sustained in the absence of strong and committed leadership remains an open question. Only 15 of the 18,000 police departments in the US have signed on to Obama’s task force, and while the task force issued a report in 2016, the Trump administration has said nothing about continuing to advance the program.95

Further, in November 2018 the Trump administration’s former attorney general Jeff Sessions enacted consent decree restrictions, drastically limiting federal oversight over local police departments. Consent decrees are court-enforced agreements between the DOJ and local police departments found to have engaged in civil rights violations and abusive conduct. The Obama administration’s effort to fight police abuses resulted in consent decrees, out of court agreements, and investigations in dozens of cities across the US, including Ferguson, Baltimore, and Cleveland.96 Under the Trump administration’s new rule, all future and existing consent decrees will be reviewed under a heightened standard that requires a showing of evidence of violations beyond unconstitutional police behavior, a sunset end date rather than a showing of improvement of police behavior, and a condition that political appointees sign off on all proposed consent decrees.97

Criminal Justice Reform Today

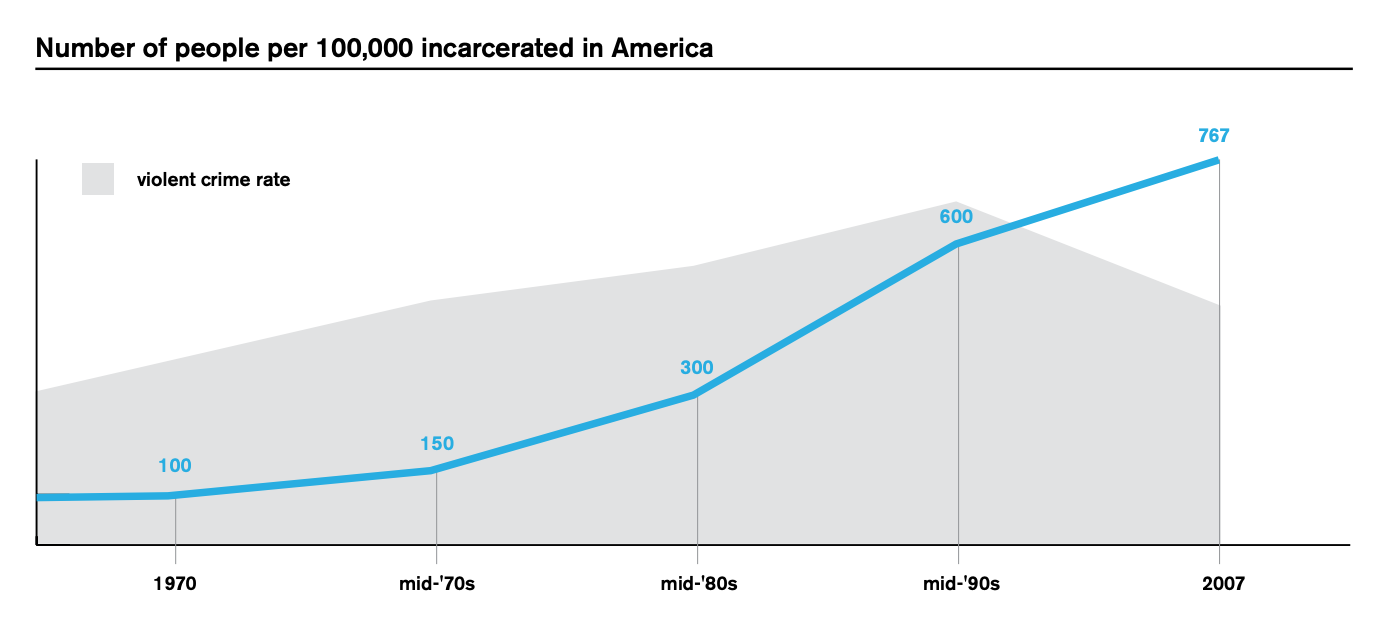

The Kerner Commission could not have fully anticipated or entirely foreseen the enormous growth in the carceral state that arose in subsequent decades. After decades of incarceration at a rate of about 100 per 100,000 people, the rate of incarceration rose sharply in the early 1970s. From the mid-1970s to mid-1980s, the rate of incarceration doubled from 150 per 100,000 Americans to 300 per 100,000 Americans.98 Then, remarkably, that figure doubled again by the mid-1990s, and reached a peak of 767 people per 100,000 by 2007. This resulted in an unprecedented rise in the prison and jail population of roughly 300,000 people to 2.2 million in absolute terms. This is far greater than any other nation on earth. A frequently cited statistic notes that although the US accounts for 5 percent of the world’s population, we have 25 percent of the world’s prison population.99

Further, the rising incarceration rate has disproportionately affected African Americans, who only make up 12 percent of the US population, but represent 33 percent of the sentenced prison population.100 In other words, African Americans experience five times the imprisonment rate of whites.101 While some of this disparity in incarceration rates can be attributed to greater social and economic dis advantages suffered by African Americans relative to whites, we do not believe that this can explain much of it, except in this respect: because young African American men are residentially concentrated in neighborhoods where disadvantage is commonplace, they are policed much more heavily and aggressively than demographically similar young white men who tend to be more broadly dispersed throughout integrated or white communities. Thus, racial segregation itself makes disparate incarceration of Black people more likely.

It should not be surprising that the rise of mass incarceration has a major racial dimension. Black men, in particular, have borne the brunt of this system, while Black families and communities in particular have been targeted and suffered by extension. This has prompted calls for a more thorough going set of reforms that extend far beyond those the Kerner Commission was in a position to imagine.

There remain many competing theories about what explains this rise in the rate of incarceration, but there appears to be broad consensus that the federal “War on Drugs” and the creation of more punitive sentencing laws and more aggressive prosecutorial efforts at the state and local level played major roles.102 The rise in incarceration, however, has occurred even as crime rates fell dramatically since the early 1990s.103

First, rolling back misguided state and federal sentencing laws is a key step toward addressing the rise of mass incarceration. Most of these laws can trace their beginnings to the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 (SRA), which was adopted amid the War on Drugs and abolished parole for federal offenders, lengthened prison terms, and led to the passing of mandatory minimum sentence laws for habitual offenders, thereby limiting the discretion of judges and parole boards. Following the SRA a majority of states enacted similar laws.104 But while violent crime peaked in the 1990s and has subsequently gone down, most mandatory sentences have remained and contribute significantly to increased prison populations nationwide.105

In 2009 New York removed harsh mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenses. In 2014 California voters passed a measure that reclassified some low-level property and drug crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. In December 2018 President Donald Trump signed a federal prison reform bill with wide bipartisan support known as the Formerly Incarcerated Reenter Society Transformed Safely Transitioning Every Person Act (FIRST STEP Act). The new legislation includes provisions that relax mandatory-minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders with no prior criminal background, expands early release programs for good behavior, offers more training and work opportunities to prisoners, bans the shackling of pregnant women, and prohibits the use of solitary confinement for juveniles.106 In 2019 at least 9,000 inmates are expected to experience sentence reduction.107 While the FIRST STEP Act encompasses the most significant changes to the federal criminal justice system in decades, it applies only to federal prisoners, who make up approximately 181,000 of the 2.1 million persons imprisoned in the US.108 Supporters of the bill, including the American Civil Liberties Union and Koch Industries, are preparing for further reform efforts in line with the FIRST STEP Act, while other criminal justice reform groups like the Sentencing Project continue to advocate for the elimination of all mandatory minimum sentences and have suggested imposing a 20-year limit on prison terms.109

Additionally, bail reform is needed to address the fact that thousands of low-income individuals are held in jail before trial because they are unable to pay. The original intent behind the bail system was to ensure that people would return to court after arraignment, but jurisdictions that eliminate their use of money bail often have as high or higher percentages of people returning for court dates.110 Further, this practice disproportionately impacts African Americans who are 2.5 times more likely to be arrested than whites, two times more likely to be detained than whites, all while African American men face bail that is on average 35 percent higher than white men for similar offenses.111 A number of states have taken steps to eliminate cash bail for most criminal defendants, including New Jersey, New Mexico, and Kentucky. In 2018, California was the first state to entirely dismantle cash bail, although some criminal justice advocates are concerned with the extensive discretion the new system provides judges. Policing low-level offenses in areas perceived to be in “disorder” under the “broken windows” theory should also be revisited and reformed.112 Although the approach was initially envisioned as a community policing tactic, it has resulted in the over policing of minority communities due to varying ideas of what “social disorder” looks like. A study in Chicago found that if two neighborhoods had identical amounts of graffiti, litter, and loitering, people perceived the neighborhood with more African Americans as one with more disorder in need of policing.113 Some cities have led the charge in walking back this approach. New York allows officers to issue civil summonses for “quality of life” offenses. Milwaukee, Philadelphia, New Haven, Portland, and Seattle have introduced police foot patrols in order to repair police relationships with the community. While African Americans in some of these cities remain concerned about excessive force and discrimination from the police, approval ratings for the police have risen in some of these cities.114

These policy prescriptions would form the core of any contemporary Kerner Commission.

Part III: Housing

The Kerner Commission and Housing Policy

The Perils of Desegregation

The Kerner Commission rejected the alternative courses of continuing present policies or simply attempting to improve conditions in existing segregated African American neighborhoods. These options, the Commission believed, would be inadequate to prevent future disorders based upon racial grievance. The Commission’s decision to endorse a third alternative—combining improvement of those neighborhoods with suburban integration—was courageous, but not courageous enough. For affordable housing advocates, it has always been too easy to give lip service to integration while attempting only to revitalize low-income minority communities. And even so, revitalization attempts have been half-hearted and conspicuously unsuccessful.

In one respect, renewed investment in low-income minority neighborhoods and promotion of integration are interdependent. Homeowners in low-income neighborhoods whose properties grow in value should be able to gain in wealth from their rising home equity, making it more feasible for these families to trade that equity for desegregated housing, should they choose to do so. Yet except in gentrifying neighborhoods, this has too infrequently been the case. Very few residents of high-poverty neighborhoods have been able to build substantial equity from homeownership, because property values in those neighborhoods have tended to rise more slowly, if at all, than values in low-poverty neighborhoods.

Too often, the integration imperative and the need to provide safe, decent, affordable housing is framed as either-or policy options. The lack of affordable housing entails great suffering by families, particularly African Americans, who very conspicuously lack decent places to live. It is an urgent and visible need. Racial residential segregation undermines the possibility of a national community with a sense of shared purpose and common destiny; this is a less immediate danger and more difficult to perceive and fully appreciate. The benefits of assuring a roof over one’s head are palpable; the costs of physically adequate but segregated housing for low-income African Americans—lower educational outcomes, reduced life-expectancy, greater unemployment, exposure to violence, dysfunctional relationships with police, and political polarization—are more indirect, but are not ameliorated by improved housing per se.

There is nothing easy about pursuing racial integration, and it can only be accomplished by those who recognize the sacrifices involved. The affordable housing crisis in 1968 was real and immediate, while the crisis of segregation was more abstract, but with profound consequences, as the Kerner Commission discovered. Both crises continue today, with neither being satisfactorily addressed.

The Kerner Commission’s 1968 report on housing began with a dramatic account of the inadequate conditions in which so many African Americans, residing in segregated urban neighborhoods, then lived. In the large cities that had recently experienced riots by dissatisfied African Americans, nearly 40 percent of non white residents occupied housing that was either deteriorating, dilapidated, or without full plumbing.115 In the specific neighborhoods where riots took place, the share was much higher. What’s more, the Commission reported that in metropolitan areas, 25 percent of non whites, but only 8 percent of whites, were living in overcrowded units.116

African Americans also paid more for housing than whites paid for similar units. Because Black families had so few areas where they were permitted to live, landlords exploited their desperation by charging exploitive rents. A discriminatory mortgage market resulted in African American homeowners paying higher interest on home loans, or being unable to obtain conventional amortized mortgages at any interest rate. The Commission concluded that non whites in metropolitan areas paid a “color tax” that was well over 10 percent of their housing costs.117 Federal programs had done little to ameliorate these conditions; indeed, the Commission charged that government had exacerbated them. In the three decades preceding the Commission’s report, government had created only 800,000 units of subsidized housing for economically disadvantaged families while insuring mortgages on over 10 million middle-and upper-income dwellings.118

Today, few families live without plumbing or heat, and fewer risk death by fire caused by space heaters or makeshift sources of heat. But partly as a consequence of stricter but well-intentioned building codes that addressed these conditions, more families are homeless and overcrowding persists. It should be obvious that requiring housing to be safer and healthier necessarily makes housing more expensive. By doing more to address safety than affordability, we’ve ensured a crisis of homelessness.

To respond to the housing crisis in 1968, the Kerner Commission proposed that government programs support the creation of 600,000 additional units of low- and moderate-income housing within the next year alone, and 6 million units over the next five years. It advocated interest rate subsidies for low-income homeowners and tax subsidies for developers of low-income housing, an expanded rent supplement program, and more public housing.

To advance desegregation, the Commission also proposed a national prohibition on discrimination in the sale and rental of housing that would enable African Americans who wanted and could afford to live in middle-class communities, to do so. Called “open housing,” the recommendation was fulfilled in the form of the Fair Housing Act two months after the Commission’s report. It has resulted in modest advances in integration for middle-class African American families. The Commission also proposed that “more” low- and moderate-income housing be placed outside minority areas. Indeed, it concluded its review of housing policy by stating:

We believe that federally aided low and moderate income housing programs must be reoriented so that the major thrust is in nonghetto areas. Public housing programs should emphasize scattered site construction, rent supplements should, wherever possible, be used in nonghetto areas, and an intensive effort should be made to recruit below-market interest rate sponsors willing to build outside the ghettos. The reorientation of these programs is particularly critical in light of our recommendation that 6 million low and middle-income housing units be made available over the next five years. If the effort is not to be counter-productive, its main thrust must be in nonghetto areas, particularly those outside the central city [emphases added].119

Surely, the commission members recognized that such racial integration would be both organizationally challenging and politically perilous. Perhaps it was courageous enough to call for desegregation, and devotion of any attention to how we could overcome the enormous obstacles would have been foolhardy. But that, of course, was the problem. The Commission was willing to go only so far. Certainly, the goal of 6 million new units was never approached, but the striking thing about this passage was its acknowledgement that continuing to put units in already-segregated neighborhoods would be counterproductive. And, indeed, the subsequent counterproductive focus of what Kerner Commission conference panelist Myron Orfield called the “poverty housing industry” on revitalization of those neighborhoods (nowadays, typically called “place-based” strategies) has reinforced the concentration of low-income African Americans and their resulting academic achievement gap, shorter life expectancies, exposure to violence, and excessive incarceration, and for the nation: growing and dangerous political racial polarization.

The Debate over Residential Segregation before the Kerner Commission Report

The Kerner Commission’s insistence on “both and”— improving conditions in minority neighborhoods and creating a priority for desegregation—was not new. It was conventional in progressive advocacy of that era, and remains so today. The belief of reformers that a near-exclusive focus on revitalization, not desegregation, would be counterproductive predated the Kerner Commission. Indeed, before the Commission began its deliberations, and before Johnson’s own political capital had eroded in the wake of his aggressive pursuit of war in Vietnam, administration officials were more explicit about the priority of integration than the Kerner Commission itself. Compared to earlier administration debates, the Kerner Commission’s advocacy of desegregation was relatively timid.

In January 1966, President Johnson proposed a “Model Cities” program to fund planning for the desegregation of metropolitan areas. In his message to Congress, Johnson said that “[t]he impact of the racial ghetto will become a thing of the past only when the Negro American can move his family wherever he can afford to do so.”120 Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Robert Weaver warned that the program funds could not be used only to improve the housing stock of existing low-income segregated neighborhoods: “[we] must proceed in tandem with simultaneous moves to open up housing occupancy to all potential customers throughout the whole metropolitan area.” Yet when the program was adopted by Congress, Johnson’s proposal that funds be used to compel metropolitan areas to desegregate was deleted. Control was placed in the hands of local officials who refused to use the funds for desegregation, and who made clear that they would not accept funds if compelled to desegregate.121

Also in 1966, a DOJ task force proposed using federal funds to induce suburbs to change their zoning laws to “facilitate the construction of non-ghetto open housing within economic reach of low and moderate income nonwhites.” Insistence on zoning reform, perhaps the most critical element in a successful desegregation program, was conspicuously absent from the Commission report—the term “zoning” does not even appear in the report’s index. Another 1966 task force, this one reporting directly to the White House, asserted that the federal government “bears a large share of the responsibility” for racial segregation because of Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration policies, and that “low-income urban families will never find adequate housing, no matter how much federal assistance is offered, unless some way can be found to break down the locally imposed barriers that prevent such families from moving out” of low-income segregated neighborhoods. The task force advocated federal subsidies for low- and moderate-income housing in the suburbs. A third Johnson administration task force on suburban problems also recommended an explicit policy to desegregate suburbs.122

Advocates of integration within the Johnson administration were resisted by a combination of liberals, conservatives, segregationist Democrats, and radical civil rights advocates of “black power,” whose priority was to revive African American communities from within. At a planning conference in late 1965, intended to lead to a full White House Conference on Civil Rights, National Urban League President Whitney Young stated that “for years in the civil rights movement we said we did not want any new schools, we don’t want any new hospitals, we don’t want anything new in a Negro neighborhood because this reinforced the segregated pattern. What is our position now?” Young answered his own question by saying that he now only wanted quality schools and facilities in Black neighborhoods.123

Many white liberals agreed with Young’s position, believing that political resistance to integration was so intense that the goal of integration was unachievable. They proposed instead programs to rebuild the African American neighborhoods into more livable and, in the view of some, even self-sustaining communities. Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward were the most influential of the liberals, writing in 1966 in The New Republic that “strategies must be found to improve ghetto housing without arousing the ire of powerful segments of the white community.” The reason we don’t invest more in ghetto revitalization, they said, was that suburban whites fear that attention to the problems of African Americans in urban areas will be an invitation to a Black “invasion.” If liberals unequivocally forswear integration, Piven and Cloward argued, more urban investments might be forthcoming.124 Their approach failed spectacularly. Since the 1960s, liberals have mostly been silent about integration, but this silence has not purchased substantial “place-based” investments that channel significant resources into deprived and historically disinvested communities. Instead, many low-income neighborhoods have been allowed to fester and decay.

Charles Haar, the Johnson administration’s assistant secretary of Housing and Urban Development responsible for administering the Model Cities program, countered by warning Johnson that Black urban areas could well require military or police occupation if desegregation did not occur. He urged state laws to ban exclusionary zoning, and proposed a “New Communities” program in which the federal government would subsidize the building of new purposefully integrated suburbs, built from scratch.125 Johnson had proposed federal aid for new towns as early as 1964, but Haar’s plea was to pursue the idea for purposes of building integrated communities. Johnson agreed, and the program was authorized in the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968, but inadequately funded to succeed.126

Kenneth B. Clark, the social scientist whose research supported the Supreme Court’s 1954 conclusion that separate could never be equal, and who testified before the Kerner Commission, argued in the mid1960s against the new fashion of compensatory education as a substitute for school integration, saying the most it could accomplish, even if funded much more generously than it was in the new Elementary and Secondary Education Act, would be a new form of “separate but equal.”127

Even this prediction was overly optimistic. Real compensatory education funding today is many times higher than it was in 1968, yet compensatory education’s share of total school

spending is about the same, and urban schools remain more separate than equal.128

These debates all took place before the Kerner Commission issued its report. The lines had already been drawn between the Commission’s reform alternatives: revitalization alone and revitalization accompanied by integration. It continued to play out in the 1968 presidential campaign when, in the Democratic primaries, candidate Eugene McCarthy advocated an emphasis on desegregation, while candidate Robert Kennedy advocated low-income neighborhood revitalization.129

George Romney’s Open Communities

Eight months after the Kerner Commission issued its report, Richard Nixon was elected president; the controversy continued to flare during the first two years of his presidency. Nixon’s first secretary of Housing and Urban Development, George Romney, embraced Charles Haar’s proposal from the previous Democratic administration to ban the use of zoning ordinances to prevent integration. Barely concealing its provenance, Romney termed his program “Open Communities,” a program to withhold federal funds from segregated white suburbs that failed to repeal exclusionary zoning rules and that refused to accept public and subsidized low-income housing.

The Nixon administration was divided over whether to support Romney’s Open Communities policy. One of its supporters was Vice-President Spiro Agnew who, before election to national office in 1968, had been county executive of Baltimore County and later governor of Maryland. He recognized that the seemingly intractable race-relations problems he faced were mostly attributable to the concentration and over crowding of Black families in Baltimore city and their exclusion from the suburbs.130

Agnew criticized the Johnson administration’s attempts to solve the country’s racial problems by pouring money into the inner city. Agnew said that he flatly rejected the assumption that “because the primary problems of race and poverty are found in the ghettos of urban America, the solutions to these problems must also be found there…Resources needed to solve the urban poverty problem–land, money, and jobs–exist in substantial supply in suburban areas, but are not being sufficiently utilized in solving inner-city problems.”131

Romney also had a key ally in the White House, domestic policy coordinator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who had advised Nixon early in his term that “the poverty and isolation of minority groups in central cities is the single most serious problem of the American city today.” Like Agnew, he criticized the Johnson administration’s approach of trying to ameliorate the problems of African Americans solely by programs designed to improve life in low-income areas. He referred to this approach as “gilding the ghetto,” and while Moynihan did not oppose additional resources for urban neighborhoods (indeed, he thought them necessary), he said that “efforts to improve the conditions of life in the present caste-created slums must never take precedence over efforts to enable the slum population to disperse throughout the metropolitan areas involved.” Focusing specifically on the educational challenge of the Black-white achievement gap, Moynihan argued that compensatory education has been and would continue to be ineffective—the real answer is to put disadvantaged children into a better environment.132

And Romney had a few allies outside the administration as well. The civil rights community was divided, with some activists supporting a priority emphasis on inner-city programs, and others favoring suburban integration. A powerful lobby, the National Association of Home Builders, supported the Open Communities initiative because its members saw profit potential in the construction of subsidized suburban housing.133

Romney then proceeded to withhold federal funds from three all-white suburban areas that refused to take steps to desegregate. He told suburban officials, “You can try to hermetically seal [your all-white community] off from the surrounding areas if you want to, but you won’t do it with federal money… Black people have as much right to equal opportunities as we do. God knows, they have suffered so much they may have more right…This problem is the most important one America has ever faced.”134

But Nixon then reined Romney in and demanded the cancellation of the Open Communities program. Romney complied, and we’ve seen nothing so aggressive since.

In 1977, Carter administration Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Patricia Harris attempted to revive Romney’s initiative, proposing regulations to withhold funds from suburbs that refused to modify exclusionary zoning laws to permit more low- and moderate-income housing. Congress rejected her proposal.135 In 1993, Clinton administration housing officials denounced the continued isolation of low-income minorities in low-income urban neighborhoods and the federal government’s past policies of exacerbating that isolation by placing public housing projects in those areas. But administration officials suggested nothing meaningful to undo this segregation, vowing only to do a better job of enforcing non discrimination laws against banks and realtors and to provide counseling to low-income minority residents to make them aware of suburban housing opportunities.136 It also promoted a “Bridges to Work” program that provided transportation assistance to help low-income urban workers commute to jobs in the suburbs. As this program did not threaten residential integration of those suburbs, it encountered little opposition from suburban officials.

The Obama administration adopted a requirement that communities analyze the reasons for their lack of integration, and propose plans to combat it. If suburbs failed to follow through with these plans and “affirmatively further fair housing,” loss of federal funds might follow. But before the initial analyses were completed, the Trump administration suspended the rule, modest though it was in comparison to the approaches of Housing and Urban Development secretaries Romney and Harris.137

Housing Policy since the Kerner Commission Report

Few of the Kerner Commission recommendations in the field of housing were implemented. Those adopted were in far more modest form or scope than the Commission believed necessary.

The Commission called for an expanded Model Cities program, despite the program’s having been stripped of its desegregation elements. President George HW. Bush’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Jack Kemp, was the nation’s most prominent advocate of using tax breaks to entice businesses to locate in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods. He was unsuccessful in getting Congress to approve his “enterprise zone” proposal, but one was finally enacted in 1993 at the beginning of the Clinton administration, and the program was expanded several times during the Clinton presidency. There was no evidence that these tax breaks succeeded in generating significantly increased employment or economic growth in the urban neighborhoods where they were employed. In 2017, tax reform legislation adopted by Congress and signed by President Trump included a new iteration of this approach, now termed “opportunity zones.” It provides even greater tax breaks for businesses that invest in low-income neighborhoods, but defines such neighborhoods so broadly that it is unlikely to provide much benefit to truly low-income neighborhoods or their residents.139

The Kerner Commission called for a federal write-down of interest rates on loans to private builders of housing for low-income families. Instead, federal policy has provided tax credits for such builders. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, currently the largest federal affordable housing program, has mostly been used to create more (and better quality) housing in already low-income segregated neighborhoods.140 Predominantly white suburbs typically have single-family-only zoning ordinances that prohibit the construction of such housing without variances, and community opposition to granting the variances is usually too great to permit builders to proceed profitably. To maximize the value of the credit, builders site such developments disproportionately in racially and economically segregated neighborhoods.

The Kerner Commission called for a rent subsidy program for low-income families. The policy adoption most similar to this recommendation has been the Housing Choice Voucher program (commonly termed “Section 8”), which has now replaced public housing construction and is underfunded. Only about one-quarter of eligible families receive the subsidy because of limited appropriations and those who eventually get a voucher have frequently been wait-listed for years. Few of those who do obtain a voucher can use them in integrated neighborhoods, also because zoning ordinances inhibit the construction of affordable apartments. Landlords in middle-class communities typically refuse rentals to voucher families, and these refusals are not considered discriminatory under the Fair Housing Act. Going beyond the Act’s requirements, some communities have prohibited refusals by landlords to rent to subsidized applicants, but most communities have not.

Housing Policy Today

Some important Kerner Commission recommendations were not implemented, even in token form. The Commission recommended, for example, an expanded and diversified public housing program. Today, we tend to think of public housing as a program for the poor, but this is a perversion of the public housing concept. When the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration created the nation’s first civilian public housing, it was designed for working-class families with stable full-time employment but low incomes. They were able to pay the full cost of the public units in rent, requiring no public subsidy. The poor were not permitted to apply. Later, as lower-income families were admitted to public housing (and subsidized), the projects became economically diverse. However, in a tragically misguided but well-intended policy shift, workingclass families were evicted from public housing to make room for the poor, whose need for adequate housing was desperate. If poor families improved their economic conditions, public housing authorities evicted them when their incomes rose above a low-income cutoff. Public housing thus became a system for ware housing the poor, concentrating poverty and the myriad ills that flow therefrom. Projects where the poor were concentrated and isolated then exacerbated the consequences of segregation.

The nation should again embrace diversified public housing as a partial solution for our housing crisis. Projects should include market-rate units where middle-class families pay the full cost of the housing in rent, as well as units of similar quality with subsidies for working-class and poor families. Public housing authorities should place such projects in middle-class suburban as well as urban neighborhoods, and particularly in gentrifying neighborhoods as a means of preserving their integration. Publicly constructed and operated projects like this are a more efficient way of addressing our housing crisis than tax credits for private builders.

Such transformation of public housing is not presently part of our mainstream policy conversation. As a much less desirable alternative, but still an improvement over present practice, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (HTC) should be modified along similar lines. The Treasury Department and state governments should create a priority in the LIHTC program for permanently mixed income projects in gentrifying or predominantly middle-class and white communities.141

In recent years, cities have implemented their own programs to create affordable housing, typically by granting height and density concessions in return for developer set-asides of small shares of units for low-income families. Cities should require, however, that the low-income families be fully integrated into the project, unlike a notorious project in New York City where a developer acceded to the set-aside requirement but then created a separate building entrance that low-income tenants were required to use.142