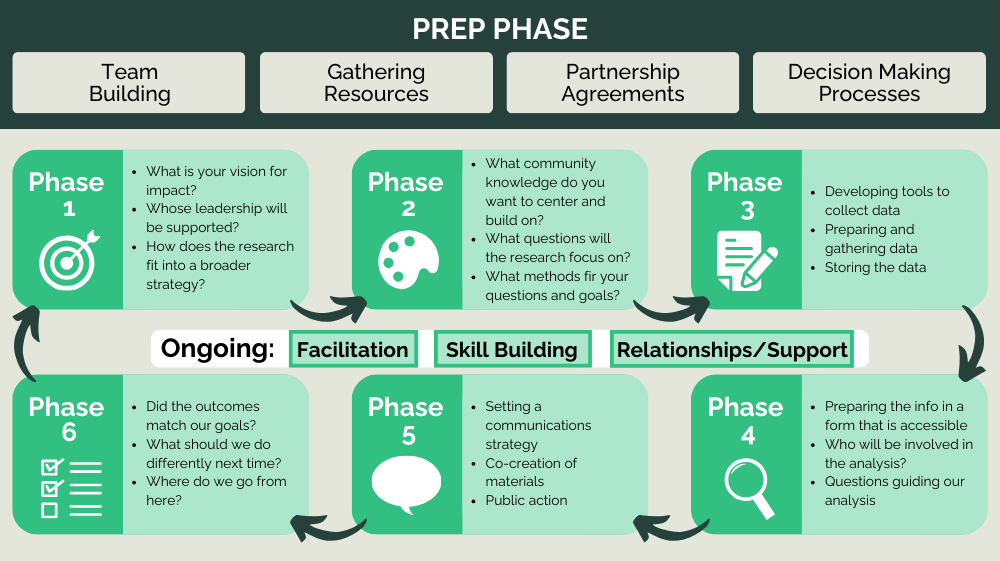

Regardless of the framework you and your team use to orient the work, understanding the stages and decision points in a research process can help everyone, including those with no formal training, guide the design and governance of your process. Each process is different, and each community will make unique decisions based on their own context and priorities. This section builds on the frameworks in the previous section by breaking down the stages in a research process, providing key questions and decisions to consider, tips on planning ahead, and resources and strategies that may be helpful.

Research Process Phases and Key Decisions

Phase 1: Setting Goals and Overall Strategy

You can start from wherever you are, even if it seems you don’t have the team or the resources to have the impact you envision. This initial stage is about developing a vision for why you want to facilitate a research process, and what values will guide you. In this phase, you may be one person getting started or a small group that has come together. Research timelines and relationship timelines are not the same—the relationships have the ability to grow and last way beyond the research.

Vision and values: What is the vision you are inviting people to move toward? What values and principles will guide you along the way? Who will be centered in the decision-making and leadership of this process? What experiences are defining the people who will be centered?

Goals and desired impact: What impact would you like the research to have on your community and the world? What impact would you like the research to have on your team and the people involved in carrying out the research? What skills, relationships, and capacities do you want to gain? What actions can you and the partners be part of to contribute to your desired impact? How do you expect to be transformed by participating in this participatory research process?

Broader strategy: At this early stage, it can be helpful to do a power analysis (see Research Methods section) to gain clarity on who currently has power around the issue, what relationships you hope to strengthen, and who you are building power with. What campaigns or existing movements is this part of or connected to? How will your specific findings move forward a larger strategy of change?

- Here is an example of a planning worksheet focused on a participatory research process that centers arts-based approaches to advancing racial justice. Feel free to adapt it to your situation!

Building a team, building trust: Building trusting and principled relationships within the team is a necessary foundation and ongoing process that is essential to collaboration. How will you begin to build relationships? What space will the group need to get to know each other? What are cultural practices that can be shared? In our experience, this can take a long time and may evolve throughout a research process. At times, a process must take a detour to repair trust if it has been broken. In the following table, we raise some of the issues that are important to discuss early as they can lead to conflict within a team if not addressed explicitly.

Key Topics to Discuss and Decide On with Collaborators

| Decision-making during the research process |

|

| Outreach and recruitment |

|

| Access and support |

|

| Resources and compensation |

|

| Credit and representation |

|

| Data ownership and privacy |

|

Ongoing Facilitation, Support, and Skill Building

Facilitation: Facilitation is the practice of posing questions, organizing conversations, and supporting a group of people to reach a shared goal they have for making a decision, gaining new understanding, or creating plans. Who will be planning and facilitating meetings and workshops? This can often default to the person with the most “authority” or the person who speaks the most. Building opportunities for shared facilitation or capacity building around facilitation can help share power and decision-making in the group. With that in mind, to make collective decisions that are strategic and have broad agreement with the team, the agendas and facilitation must offer structure and principles.

Skill building: What technical skills are needed for the community researchers to own, plan, and carry out the research in each stage? What training and advising will be needed, and who and how will this be offered? What skills are already on the team and in the community that might lend themselves to particular research methods? These questions are especially relevant when you decide on your research methods, which are explored in-depth in the Research Methods sections of this toolkit.

Support structures: What support is needed so that each member of the team can fully engage in the project? If issues outside of the project arise that create barriers for people to do the work, who is available to provide the support needed? This may be related to situations that arise in the lives of members of the team, such as losing housing, experiencing trauma, or dealing with other challenges. It is important to take time and extend support, which may look like helping someone connect to a service provider, providing mutual aid, or advocating alongside the person as they interact with public systems.

Related Resources

- Participatory Workshops: A Sourcebook of 21 Sets of Ideas and Activities, by Robert Chambers, is a practical guide with many activities for facilitating participatory workshops and meetings. It provides tips, common mistakes, questions to ask yourself, and specific activities that can work as openings, energizers, and evaluations. It also includes insights on setting up the room, forming groups, and adjusting methods for larger groups of participants.

- Moving Beyond Icebreakers, by Stanley Pollack and Mary Fusoni, has over three hundred exercises for interactive workshops, organized into groups based on the purpose that they help achieve. The book also provides tips on designing interactive workshops, building agendas, and getting started with facilitation.

- The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership, by Facilitating Power, provides a framework and practices for different levels of community power in a decision-making process.

Partnership Agreements

Written agreements can formalize important decisions about roles, responsibilities, resources, and other key decisions. These are especially important when multiple organizations are collaborating or there is a difference in power or need to build trust between members of the collaborative. These agreements can take the form of a contract, which can be more legally binding and cover the distribution of funds. Or the agreement can be a less formal memorandum of understanding (MOU) or statement of principles of collaboration. It’s also worth noting that some people may not want to work with written contracts because they come out of histories of racist property ownership or punitive outcomes. In these cases, building out a process for regular check-ins, tending relationships, and moving at “the speed of trust” is essential.

Template for Partnership Agreement

- Goals for impact: describes the impact that the partnership is committed to achieving. It could include specific products (e.g., reports, visuals, events), changes to community conditions (e.g., train five hundred residents in community air monitoring), or major activities (e.g., design and implement a community research project focused on prison abolition).

- Principles and norms for how we will work together: describes the way that the partners will relate to each other and approach the work. This can be high-level values (e.g., center the voices of the most impacted, prioritize healing) or ground rules (e.g., step up and step back, be hard on ideas but soft on people). Other issues it might address include how we will make decisions, how we will define and uphold confidentiality among the team and between those participating in the research, and how we will obtain consent from community members engaged in the project.

- Roles: describes who is going to fill the main roles in the project. It could identify a point person for each organization, a project lead, a person coordinating trainings and workshops, a technical assistance lead, a lead artist, etc.

- Resources: describes how money and other resources will be secured, held, and distributed. This can include commitments to joint fundraising, a specific breakdown of how much funding each partner will receive, or a set of principles about how any resources will be shared.

- Data ownership and sharing: describes how data will be gathered, stored, and shared to make sure any security, privacy, or data sovereignty needs are met. This can describe who is going to have access to specific datasets, who is allowed to make decisions about sharing data with others outside the project partners, or a decision-making process that will be followed before any data is shared outside the project.

- Timeline: describes the overall timeline for the project, the timing of any important milestones, or any principles or goals that require sensitivity to timing (e.g., a goal of having materials ready for the public at least two months before the city’s next budget vote). Every PAR process comes to an end or a transition when the formal project concludes. Having discussions about the possibilities of relationship cultivation and transformation post-research process is important.

See sample MOU by the environmental justice organization West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project that was an agreement with their partner, the Environmental Defense Fund.

Collaborating with Academics and Technical Experts

Often, a PAR process may involve academics and technical experts. How you involve them in your team and process can have a major impact on the power dynamics, the capacity to finish the research project, and the usefulness of the research. Technical experts like academics, graduate students, or consultants can bring helpful capacity to design the research, process data gathered, and write up the findings. But these collaborations also require intention and care so that they do not replicate power imbalances, redirect the research away from your goals, or create other challenges.

There are some common challenges related to working with academic researchers to be aware of and address. In terms of time frame, academics typically work within a semester-to-semester calendar, so they may be under pressure to finish a project during a semester or before the semester starts. Second, universities usually value academic publications, not community reports or public actions, so academics feel pressure to publish articles about the research they do. This pressure pushes them to focus on questions relevant to “the literature” (the current debates among academics), which may differ from the questions the community has prioritized.

There are benefits to working with academics: they can bring needed technical expertise, critical concepts, and teaching skills. They usually don’t charge a fee, and they have access to and knowledge about libraries, databases, and other technical experts. They can also lend credibility to whatever is published or presented to the public.

See the UCLA Social Sciences Division’s “Guidelines for Evaluating Community-Engaged Scholarship in Academic Personnel Review,” which is a helpful resource when establishing partnerships with academics.

Data Ownership and Use

While it may seem like a conversation that can wait, decisions about who has access to and uses the data gathered can help you define roles in your research team, choose which research tools are appropriate, and ensure your community that the research is being carefully planned to avoid any harm that could come about.

Data ownership is complicated by the common use of digital technologies created by corporations that regularly gather data on user behavior and use it to predict, influence, and profit from people’s future behavior. This economic structure, known as surveillance capitalism24 or data capitalism,25 drives corporations to attempt to gather ever more detailed data about ever more people.

You can choose which ownership rights you would like to hold over the original work that you put out. Creative Commons is an international framework with several different types of rights that you can select and then use their language and symbols to declare those rights. For instance, this toolkit is licensed under Creative Commons license BY-NC-SA, which stands for “Attribution, Non-commercial, Share-Alike”. This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only. If others modify or adapt the material, they must license the modified material under identical terms. This type of license is represented by this symbol:

The Detroit Community Technology Project has guides, curriculum, and examples of strategies for community-designed and owned technology, including “Our Data Bodies,” a popular education curriculum focused on data, surveillance, and community safety.

The “Surveillance Self-Defense” guide by the Electronic Frontier Foundation has a series of explainers to understand key concepts, practical guides for ensuring data security, and scenarios for thinking through how to defend against surveillance.

There are three fundamental questions to consider in thinking through data ownership:

- Who will have access to the data while it is being gathered, stored, and analyzed?

- What will the data be allowed to be used for?

- How will you make decisions about data security and use?

Phase 2: Deciding on Research Questions and Methods

Deciding on research methods is about orienting your research toward what you need to most powerfully move toward transformation. To build power and change systems, we often need several types of knowledge. Unless you have endless resources and time, you have to prioritize.

The Research Methods section in this toolkit gives in-depth guidance on eight different methods. Before you skip ahead to that section, you may want to think about what your overall goals are and think about how different methods compare. The following table starts with the ingredient for transformation, or what you need to catalyze action or organizing work. The second column lists what types of knowledge help create this ingredient. Column three points you toward suggested research methods.

As you go through the table, keep in mind that you might have secondary goals such as building relationships with your community or strategic “validity” or “legitimacy.” These considerations can help you fine-tune your choice of research method.

Ingredients for Transformation and Related Research Methods

| Ingredient for Transformation | Knowledge Needed |

Research Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Analyzing the issue or problem in the community |

|

|

| Root cause analysis of what is causing the problems in the community |

|

|

| Analyzing potential solutions and policy changes |

|

|

| Power networks and decision-making processes |

|

|

| Accountable implementation of policies and programs |

|

|

| Public narratives |

|

|

Phase 3: Collecting Data

The Research Methods section of this toolkit gives more detail about how to use specific methods for data collection, but the basic components of collecting data are:

- Developing the tools: Taking time to carefully develop, try out, and refine your research tool will help avoid a later moment when you might regret not asking a particular question. Examples of tools are the list of questions for oral history interviews, the base map for participatory mapping, or the criteria you use to select sites to visit to learn about potential solutions.

- Preparing to gather data: Preparation includes training and practicing gathering data.

- Gathering data: This is where you want to be as methodical as possible, sticking to your plan and consciously adjusting it if needed.

- Storing data: Keep the data safe from being accidentally erased or altered, or from being accessed by someone who doesn’t have permission to see it. See our discussion of data ownership for more nuance on this.

Phase 4: Analyzing Data

Analyzing the data is when the group makes meaning out of what the collected information shows. This can be an ongoing process of reflection over multiple sessions or even over several years. You might ask something like, “What does it mean that X percent of people said that Z was true?” Or “Why do we think that all of the X are located in this area?” This is where you are looking to hear and affirm community narratives that make sense of and use the data. It is key to be honest about ways that the data might surprise or go against some assumptions.

Processing and Visualizing Data

Raw data is generally too vast for it to be a good resource for community reflection. Showing a spreadsheet at a community workshop can bore and intimidate people. So there is often a step where a trusted subset of your team will process raw data so that the essential information is synthesized and made accessible. It can also be the stage when academics “disconnect” from people who don’t have this training. If you are able, this is a great place to build the capacity of the entire team, or for the person who processed the data to show how they did it so that the process itself can be demystified. Synthesized data can include:

- summary statistics

- themes and quotes

- maps or charts

- specific stories

- slideshows

Facilitating Community Analysis

To gather fellow community members to discuss how everyone interprets the data, it is helpful to prepare interactive formats and give everyone ample time to think about and express their interpretation in multiple ways. Some examples of this are:

- Gallery walk: In this activity, posters with visuals of the data are put up around a room like in an art gallery. Participants walk around the room and talk about what they notice and write notes next to each poster.

- Family Feud: Just like in the TV game show Family Feud, ask participants to guess what answers were given to survey questions. It can be a fun, interactive way to review survey findings, followed by a discussion.

- Small discussion groups: sometimes the best approach is simply gathering in groups of three to five people to look over the data and discuss it using some guiding questions.

Phase 5: Public Action

Setting a Communications Strategy

Congrats! You planned and did the research with your team, and now you have relevant new data. Your group is in a powerful position to take action. But before you do, it is worth developing a communications strategy that allows you to be clear about who you most want to reach, the best way to reach them, and who will be the messengers. This is a good time to revisit your power mapping, which clarifies who the key decision-makers are, who has power, and who needs to be educated and mobilized.

A communications strategy has a few basic elements:

- audience: who will receive the message

- messages: what is being communicated

- messengers: who will get it out

- strategy: how you will get it out

- work plan: for internal planning and deadlines

See Communication Tools by Spitfire for useful tools for writing a communications strategy.

Cocreation of Action Materials

A community workshop agenda, report, fact sheet, flyer, or other materials are more powerful if they are created through a collaborative process. Once you have decided on a communications strategy, you can start making the materials you will use in that strategy. A basic process for cocreation of materials is:

- Decide on roles for who is doing the writing, feedback, visual design, etc.

- Begin initial writing or creation to develop a draft

- Solicit feedback from specific people who review the draft

- Discuss the feedback

- Revise the draft to create a final draft

- Decide if the final draft needs anything else before it is distributed (go back to the previous step if it’s not ready)

Collective Action

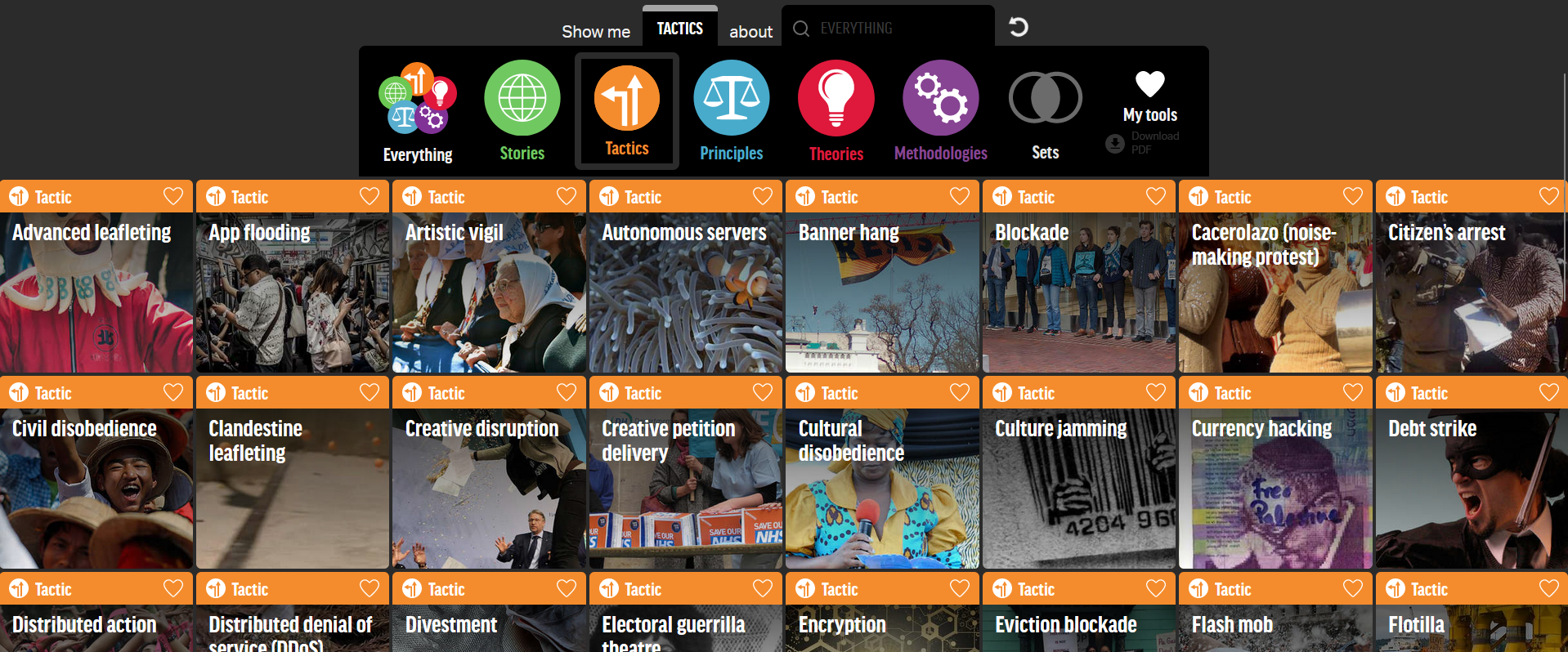

There are millions of types of collective actions (for ideas, see Beautiful Trouble Toolbox). How does the action embody the message that the group wants to send? How are the research findings shared in an accessible and compelling way? How does the action reach the people who most need to be reached? How will the impact of the action be measured?

Phase 6: Evaluation of Impact and Lessons Learned

At this point, we are often tired and feeling pulled into other work, so it’s tempting to skip a real evaluation of impact and lessons learned. You have done your research, learned from it, and taken action with it. What did you learn from the process? What has the impact been? What was made possible in the world? What makes sense to focus on next? Who do you want to share these lessons learned with?

Questions to reflect on your impact:

- What new knowledge was created?

- What relationships were created or strengthened?

- What opportunities for policy or institutional change have appeared?

- How did public narratives about the issues and community shift?

- Were there any unintended or unexpected consequences?

Questions to explore next steps: