Power analysis and power mapping visualize the relationships between different stakeholders, which can include and are not limited to organizations, individuals, elected officials, coalitions, and schools. These relationships are analyzed based on decision-making power and the position the person or group takes toward your goal, or positionality.

Upon mapping stakeholders, the tool can be then used to identify clusters of stakeholders with similarities in their positionality or power. These clusters are then used to inform your group’s strategy for building relationships, educating people, and transforming power dynamics.

Types of Knowledge That Power Mapping Generates

First and foremost, it is important to have a conversation about power. What is power? Power is commonly described with a negative connotation and is often used to refer to a form of authority, control, manipulation, or domination. The power we are most familiar with can be described as “power over,” where an institution or person has direct control over the behavior of others. It can become difficult to identify the institution or person holding the power when they have been exercising that power over a long period of time.

“Power over” is the ability to influence a person’s or a community’s behavior, perception, resources, access, opportunities, and safety over time. Power over is enforced through violence or the threat of violence or through reward (profit, protection).

The book A New Weave of Power, People, and Politics summarizes the ways in which power can be reframed in a positive manner:

- “Power to” is about being able to act. It can begin with the awareness that it is possible to act and can grow in the process of taking action, developing skills and capacities, and realizing that one can effect change.

- “Power with” describes collective action, or solidarity, and includes both the psychological and political power that comes from being united. “Power with” is often used to describe how those faced with overt or covert domination can act to address their situation: from joining together with others, through building shared understandings, to planning and taking collective action.

- “Power within” describes the sense of confidence, dignity, and self-esteem that comes from gaining awareness of your situation and realizing the possibility of doing something about it. “Power within” is a core idea in gender analysis, popular education, psychology, and many approaches to empowerment.50

The Power Map

The first step in creating a power map is to define the goal, vision, or interest that you are going to focus on in your analysis. You will be analyzing how people and groups relate to this goal. Are they opposed to it? Indifferent? Strongly supportive?

The power map is a chart that has two dimensions to place each person or entity on the map: their power to influence achieving your goal, and the degree to which they agree or disagree with the goal. Let’s talk about the x-axis (horizontal line): this axis focuses on how strongly someone supports or opposes your goal. The y-axis (vertical line) measures the amount of power a person or organization has in order to push your work forward or back.

Prior to power mapping, you have already established relationships with community members and other people involved in this work. The map should be cocreated alongside those community members. Beginning with an empty map, use the following questions to guide your conversation to determine who should be a part of the map:

- Who are all of the types of individuals or organizations that have a voice in the problem you want to solve?

- Who is directly impacted by this work? Who is indirectly impacted by this work?

- Who supports the goal we want to achieve?

- Who opposes the goal we want to achieve?

Go through the questions one by one and decide where to put them on the power map. For this analysis, you can rely on the knowledge of the people in the room, or you can incorporate additional methods for gathering relevant information. Some organizers carry out interviews of knowledgeable people in their region, asking them questions about who has influence and what their interests are. This approach can provide a more accurate power analysis because it integrates information that may be missing from your core group. Another option is to look at data on campaign contributions, public statements in the media, or other records showing what influence and interest people have demonstrated.

Note: Given our different definitions of power earlier, there may be debate around what kind of power you are discussing here and what different kinds of power can do for achieving the goal. This is a good opportunity to talk about what it means to build different kinds of power.

Analysis of Clusters and Networks

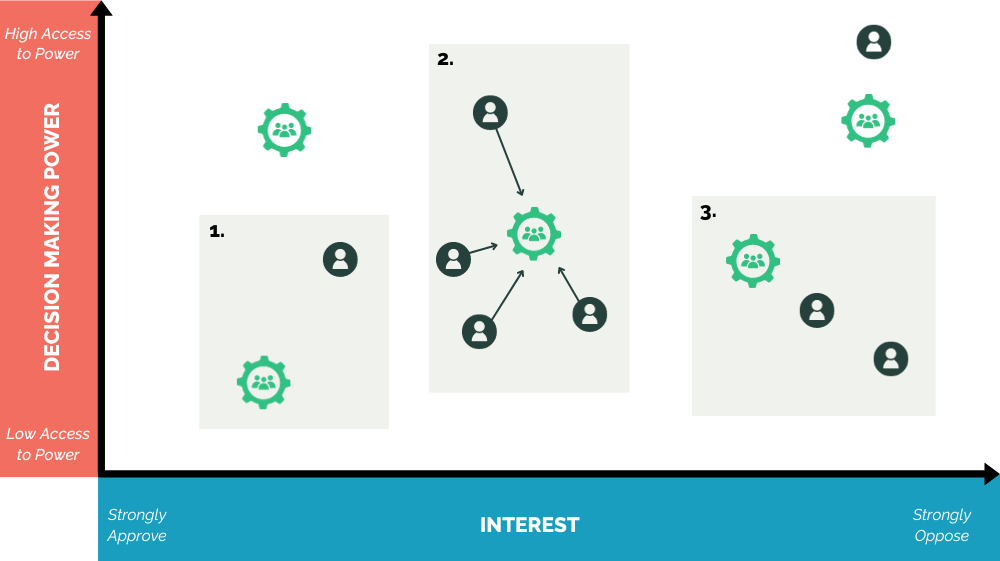

After placing individuals and organizations on the map, you might be able to see some patterns and relationships. You might also have noticed that there are a couple of places on the map that are empty. This is where an additional layer of research might be needed by asking, What do we know about the people on the map? Who is still missing that we should add?

Organizations are represented by the light green circles, individuals by the dark green circles, and clusters of power by the shaded gray squares.

In some cases, you might see a cluster of individuals and organizations. We want to focus on connecting the dots between these clusters to understand the power relationships among the networks.

How Power Analysis Can Build Relationships and People Power

Power mapping can enhance your group’s understanding of the political context and your ability to think strategically. It can also build trust and shared understanding between participants in the group as they work together to develop each step of the research, discussion, and mapping process. As you identify key stakeholders and clusters, power mapping can facilitate the creation of new relationships with attention to power: Who is the key council person or city staff to build with? What organizations are already well-placed to affect this issue and how can you support them? By clarifying where to focus your group’s work, it builds your group’s power through more intentional action to advance your goals. Power analysis can be facilitated through interviewing, base-building dialogues, cafecitos, oral histories, and other formal and informal research processes that can be used to identify stakeholders that should be added to the map.

Time, Capacity and Resources, and Tools Needed

Depending on an organization’s capacity and financial resources, a power mapping activity can be done in a workshop, over a series of workshops and training, or as part of an initial phase in the larger context of the work. Power mapping activities are meant to be iterative and interactive. Some materials you will need to complete a power map include sticky notes, butcher paper, tape, markers or color pencils or pens, and thread.

Power mapping activities can also be completed digitally. Here are some software and platforms that can be used to create an interactive, yet digital, power map:

- Google Jamboard (free)

- Miro (free option, other advanced features will require a subscription)

- PowerPoint (free, will require Microsoft Office)

Pitfalls, Challenges, and Myths

Things change! This tool is a point-in-time visualization of power dynamics. Power maps are never complete; your map will change depending on the length of the work, power maps, policy, and cultural shifts. As a result, it is important to stay in relationships with stakeholders mapped. Power is constantly changing and shifting, so there’s always room to update a power map. Additionally, knowing when to end an iteration of a power map can be challenging given that power dynamics are constantly changing and shifting and essentially everyone might be affected by the problem or issue that is trying to be solved.

Differing analyses: Within your group, you may have different perspectives about the interests and decision-making power of a person or organization. Additionally, members may have differing definitions of power and the relevance of stakeholders mapped, or folks might define decision-making power differently. It can be helpful to take time to discuss and make sure that this isn’t creating wedges in your group.

Check your tools: While a power map may serve as an organizing tool, it is important to not allow the map to dictate the entire trajectory of the work. There are going to be external forces that might affect power relations that are not going to be in your purview.

Getting specific enough: Power maps are strongest when they are specific. In other words, name names! Make sure to differentiate in the map between individuals and organizations. For example, you might classify individuals as circles and organizations as squares. If you are naming organizations, you might want to then research who the key person is at the organization: is it the executive director, a key member, or the chair of the board?

Weaving in Cultural Strategy

As noted, one way to integrate cultural strategy in a power mapping process is to simultaneously “map” other types of power that are being built or could be further built in the process of discussing power.

One way to do this is to reflect on the struggle, joy, sacrifices, and love of ancestors and elders that have created the conditions from which your PAR group is doing the work today. What types of power did they create or return to that might not fit on your power map? How is your process building on these sources of power (such as ritual, religious, or spiritual practice) even if they don’t contribute to a direct campaign goal? By naming and discussing these sources of power, you connect your process to a longer thread of action. You also remind yourselves that although a campaign outcome may not directly impact the individual PAR researchers, it is contributing to larger shifts in power. For example, in a PAR process that successfully increased tenant power, one PAR researcher reflected on how the process gave them a deep love for their city (power within, place-based power), which committed them to continue to fight for it and its people. Because their situation changed, they didn’t benefit directly from the policy win, but they benefited by building other types of power.

In discussing power, a PAR group can also identify the types of power they want to intentionally build through the process. This might mean the integration of traditional knowledge in a process, the intentional deepening of relationships through shared meals, or opening every meeting with a short group dance activity that connects people to each other and their roots. Maybe this dance activity relies on heteronormative roles and the group decides to reclaim it by queering it. The cultural strategy invitation is to think about how you are building power within a longer culturally specific context that comes before and lives after a finite PAR process.

Related Resources

- “How to Lead a Workshop for Stakeholder Mapping” by Hayley Pontia, Beeck Center for Social Impact and Innovation

- “Map the Power: Research for the Resistance” by LittleSis

- “Stakeholder Mapping” by the Reproductive Health National Training Center

- “Strategic Concept in Organizing and Policy Education” by Strategic Concepts in Organizing and Policy Education

- 50Lisa VeneKlasen and Valerie Miller, A New Weave of Power, People, and Politics (Practical Action Publishing, 2007), https://justassociates.org/all-resources/a-new-weave-of-power-people-politics-the-action-guide-for-advocacy-and-citizen-participation/.