Interviews are useful for gathering stories, deeply held beliefs, metaphors, and other knowledge and building one-to-one relationships with the community. Interviews are often thought of as a direct, simple, and trustworthy research form. Part of their trustworthiness is based on an interview’s emphasis on a spoken answer. Artists can play with this format by bringing in other forms of expression (movement, visuals, poetic responses), creating more comfortable and intimate contexts, and bringing interviewees into the process of developing or interpreting the interview questions. This supports interviewees and storytellers in sharing their authentic feelings, as opposed to what they think they should feel (social desirability bias) while also expanding the notion of what “data” is and how it can be collected. This expands the types of knowledge to draw from when understanding and solving a problem.

A Black and Brown queer-led effort called MoralDocs in Providence, Rhode Island, used interviews as part of a research-based, cultural strategy process focused on abolition and health justice in their community. Vatic Kuumba and Shey Rivera were the leading artists of the collaborative, which was made up of system-impacted community members and artists and PrYSM, an abolitionist, youth base-building organization. The group also sought support from a PAR and health justice consultant and longtime community ally, Justice Alchemy. The group conducted interviews with community members to gain insights into their community’s experiences with public safety and law enforcement systems. They also facilitated a meditative visualization activity asking community members to imagine their visions for a healthful, liberated future.

The interviews uncovered knowledge on dynamics with community members and the police and fire departments. They also held space for storytellers to share their stories, emotions, and desires on their own terms while also staying focused on the priorities established through prior aspects of the project. The visualization activity built experiential capacity for storytellers to imagine a generative, expansive, healthful, and liberated future. Bringing this into the research method intentionally weaved life-affirming ways of knowing into the process that otherwise may not have been uncovered.

With the storytellers’ consent, the collaborative used the interview data, survey data, and secondary research to bring fictionalized versions of the community members’ narratives to life on screen via a collaboratively written multimedia series. The series envisioned what it might look like to achieve a safe, healthy, and liberated Providence in the not-so-distant future. Additionally, the group organized to gain access to and influence a public safety department’s assessment process and report done by a consulting firm working for the city. The group used the data from the report and their own interviews and secondary data to put out a narrative of what the city needed from a frontline community perspective. This effort helped substantiate the need for reallocation of funds from punitive and militaristic measures to life-affirming, health justice, and community-led programming.

What Type of Knowledge Interviewing Generates

Interviews provide knowledge on the underlying processes, dynamics, emotions, and histories that other methods, like surveys and focus groups, do not. Interviews offer an opportunity to collect in-depth, tender perspectives expressed in people’s own language and logic. They can generate collective knowledge from day-to-day and lifetime experiences by centering community voices and expertise. The data is not generalizable to a broader population because the sample size is small and intentionally not randomized. For example, interviews will not give you reliable data about what percentage of people feel a certain way or have experienced a specific event. However, because PAR projects are led by community leaders determining their own research priorities for action in their own community, you may decide that the depth of why people are experiencing something is more important than data on how widespread an experience is.

How Interviews Can Build Relationships and People Power

Interviews create an opportunity to establish and deepen relationships, build community leadership, and create a point of contact to link people with organizing networks. One effective way organizers can use interviews is to generate testimonies that can be told as part of a campaign and media strategy. Interviews can also preserve community history and records and assert community narratives that dispel assumptions and stereotypes that dominant media and society project on you and your community.

Interview data can also build shared knowledge to foster community healing while strengthening community capacity for organizing. When an individual is given the opportunity to take space to tell their story, it can activate “power within,” and in sharing community stories (if consent is given), it can cultivate trust and empathy among participants. Storytellers may decide to join the PAR team and project. Having community members learn how to interview, process data, and analyze it is another way interviews can help build power in a PAR process. These skills equip community members to lead their own research on their community and to bring these transferable skills to other parts of their lives.

Time, Capacity and Resources, and Tools Needed

To honor the storytellers and ensure a quality analysis, it’s important to budget enough time to hold the interviews (typically two hours) and to analyze data. You will need ample time (more time than you’ll think) for planning, recruitment, conducting interviews, processing and analyzing data, and reporting out the learnings. Interviewers can have varying skill levels depending on the interview design you use (see below Table 1).

Overall, an interview is a low-cost, generally accessible research method as you will only need an accessible, inviting place, a recording device, a computer, an ability to print transcripts, and, ideally, multiple computer screens for ease of transcript review and analysis. You may also need translation and an interpreter if interviewers do not speak the same language as the people being interviewed.

Interviewers require sensitivity, compassion, and healthy boundaries. For example, when discussing traumatic and sensitive topics, interviewers should bring a high level of emotional intelligence and skills in discussing painful topics with consent, care, and respect. You may experience vicarious trauma by virtue of holding space for your storytellers and interviewees. So, it is important to use self-care practices as interviewers for your own well-being.

If you use transcription tools like Zoom’s auto-transcribe setting or Otter.ai, it will significantly reduce the time it takes to process the data, though it will still require a transcriber to review and correct any mistakes from the auto-transcription. For the analysis process, while not necessary, you can also use coding software like NVivo, MAXQDA, Dedoose, or Taguette. You’ll also need capacity and understanding in data privacy, protection, and storage.

Interview Question Design

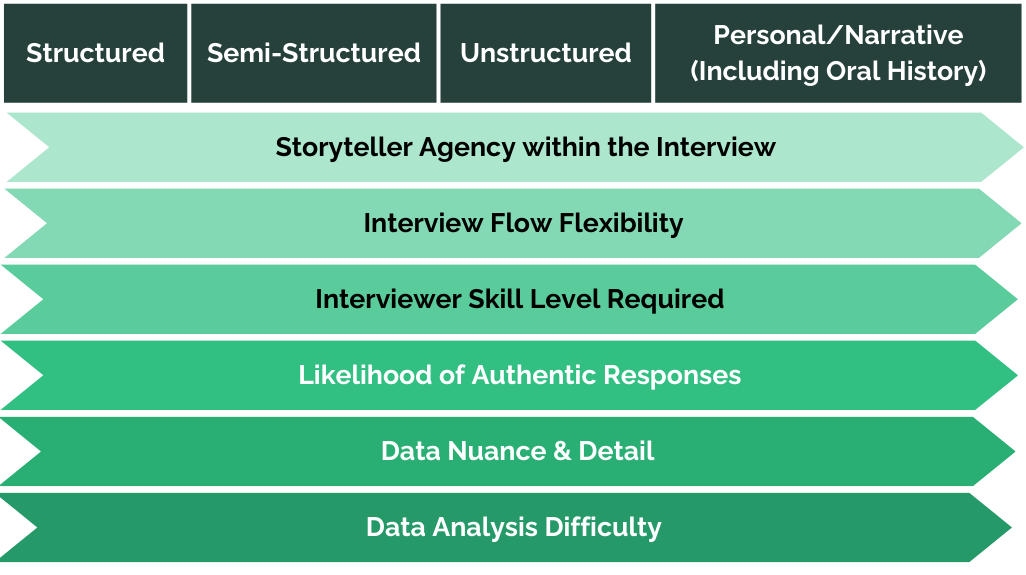

Choose an interview design based on a research strategy that considers community context, values, principles, priorities, resources, and capacities of the PAR effort. The interview design includes structured, semistructured, unstructured, and personal narrative interviews.

Structured interviews are useful for specific data collection, while semistructured interviews strike a balance between flexibility and focused questions. Unstructured and personal narrative interviews give participants agency and control over the conversation.

Table 1: Spectrum of interview types and associated characteristics

PAR processes typically lend themselves to using interview types that center the storyteller’s instincts, agency, and control over the pace and flow of the interview. However, it depends on the timing, sequence, and context in which the research method is being used. For example, if there is already an understanding of the issue at play and the purpose is to hone in on some specific aspects within it to inform survey data or the larger narrative, more structured interviews may be most appropriate. Also, as described in the MoralDocs’ example, semistructured interviews allow for artists and cultural strategists to provide creative prompts and activities for interviewees while also providing open-ended space for interviewees to share what’s in their hearts and minds.

Conducting the Interviews

Create a supportive and inclusive environment that encourages interviewees to share authentically and openly. Keep your questions clear and concise, and try not to ask two questions in one or use double negatives. Lean on your existing skills in holding one-to-ones and bring your other community weaving strengths in conducting PAR interviews. This is a great time for leadership development in training up community interviewers. This can also further connections across community members as a result of community members interviewing each other while also collecting data for the PAR effort.

Lastly, just as with other forms of research, receiving informed consent, outlining how the data will be used, and providing a space where participants can stop at any time in the interview is essential.

Processing the Data

Participatory data processing often includes community members transcribing interviews. It is a generally accessible activity, and it gives people a chance to spend time listening to their fellow community members’ stories. Another important way to center community ownership over the research is to share back completed transcriptions to interviewees to review and make any adjustments to what they said.

Analyzing the Data

Analyzing the data begins with listening to and reading transcripts and identifying quotes and themes. Sometimes it is worthwhile to create a list of codes based on the themes you’re most interested in, and then go through the transcripts and mark places where each code or theme is discussed. One process for collaborative analysis includes having a diverse, smaller analysis team that collects the quotes and themes and shares them out to the larger team for discussion. Depending on the context of the research and community, you may also identify significant decision points in the analysis process to share with community members or community representatives before going to the next analysis step. This is one way to minimize biases within the smaller PAR team, ground truth learnings, and continue to deepen community leadership and investment to the project.

Pitfalls, Challenges, and Myths

Unconscious bias can influence an interview process when the interviews ask questions in ways that reproduce beliefs rooted in white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, and othering. The framing of a question can suggest what is an appropriate answer, which is where the bias of the interviewer can shape the responses. While movement builders aim to decolonize and unlearn dominant ways of being, sometimes we can fall into a habit that doesn’t align with our beliefs (decolonizing is a lifelong, daily practice!). With interviews, it is easy to unintentionally insert or project our viewpoints into what the storyteller is sharing, and this can also play out in the analysis and sense-making stage.

Keeping in mind the positionality of yourself and the group is a good way to increase awareness on how habits and dominant ways of being might inadvertently show up throughout the PAR process so that you can course correct as needed. Collaborative processes with a diverse team is an effective way to mitigate unconscious biases because the group can share data interpretations across other individuals’ responses with differing positionalities. This can involve practice runs of interviews to see how different people respond to the questions.

Weaving in Cultural Strategy

In one interview process about trusting city government, the research team used metaphor questions to ask about residents’ relationship to government. The use of metaphor opened up interviewees’ storytelling for added complexity. For example, when asked directly about how they thought about government, a resident said, “I don’t pay any attention to it.” When asked what metaphor it was, they shared that it was like a mango, which they had experienced as an overhyped fruit, expensive and too hard to get when it tastes good. This metaphor opens up further questions about dominant narratives about government, accessibility, and timeliness of services.

The dancer Bill T. Jones has used movement-based responses to explore experiences of people living with terminal illnesses. The interviewees then become choreographers and dancers as they collaborate to create group pieces out of this initial “interview.” The poet Ciera-Jevae Gordon interpreted interviews she conducted around displacement through a book of poems, identifying overlaps through themes in the poems and creating a transparent “research interpretation” through her artistic intervention. Finally, the artist Brett Cook usually develops a set of interview questions by asking all of the interviewees to contribute one or two questions around a theme.

Related Resources