In March 2020, just eight days into the first coronavirus lockdown, Janet Lymer, like thousands of others across the UK, was setting up a volunteer group to support people in need in her local area of Calderdale. Calder Community Cares mobilised local people to deliver food parcels and medications, to lend people books and board games, to provide digital support with video calling, and to make phone calls to check on elderly and house-bound residents. Despite being unable to leave the house herself due to asthma and a serious lung condition, Janet created a thriving support network for those in need in Calderdale.

Belong interviewed Janet as a part of our Radical Kindness project, which involved collecting inspiring stories of people and organisations that bridged different communities during the pandemic. It was clear that Janet had been overwhelmed by the support for Calder Community Cares and felt she had benefited from her involvement as much as those she had helped.

“[…] there is a lot of kindness in Calderdale and it’s just a case of harnessing that. Right from the beginning, people wanted to help. Within just a day of setting up Calder Community Cares, we had people registering for support, but that was quickly matched by the same number of people asking to volunteer. Some of the people who initially signed up to receive support have then gone on to volunteer themselves. Kindness really does beget kindness.”

Calder Community Cares continues to offer support to residents and exemplifies the spirit of kindness and generosity that characterised those early days of the crisis. Inspired by this outpouring of kindness, Belong’s Radical Kindness project has sought to showcase examples of kindness that bridge differences between groups and forge stronger, more compassionate, social connections.

Belong - The Cohesion and Integration Network is a charity and membership organisation founded in the UK in November 2018. Our vision is for a more integrated and less divided society. We exist to strengthen trust and social bonds in and between different groups and communities in society. Belong supports and connects people and organisations across sectors with practical tools, networks, inspiration, learning, and resources to achieve real change. We advocate for work that strengthens good relations across difference and addresses underlying drivers of segregation and disconnection. With our members, we are building back social connections, trust, and unity from the ground-up.

Our Radical Kindness project drew on findings from qualitative research conducted as part of ‘Beyond Us and Them: Societal Cohesion in the Context of Covid-19’, a major research project funded by the Nuffield Foundation and conducted by Belong and the University of Kent. In this article, we present learnings from our Radical Kindness project. We position radical kindness (defined below) as a key element of social cohesion programmes and illustrate its power for reshaping community relations to create new visions of belonging and to challenge narratives of fear and division, especially in times of crisis.

In the first section, we examine the concept of radical kindness and delineate its differences from situational, random, or relational acts of kindness; in the second section, we highlight some of the barriers that might prevent radical kindness from thriving; and in the final section, we give examples of radical kindness drawn from the expertise and experiences of six local areas that invested in social cohesion prior to the pandemic1 and of charity, business, and volunteering organisations. In doing so, we celebrate the benefits of strong intercultural and intergroup community relations and profile the proactive work of individuals, organisations, and communities who have sought to support those who are different from them throughout the pandemic. We contend that radical kindness is a powerful way of promoting social cohesion, addressing underlying prejudice, and helping us to move beyond narratives of ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Defining radical kindness

Empathy, compassion and kindness have been taken up and deliberated across the ages and in a range of disciplines. Kindness and compassion and ideas of neighbourliness are a central strand of all of the major world religions. Prosocial behaviour and altruism are studied by, amongst others, evolutionary biologists, social anthropologists, and economists–each of whom proposes a range of hypotheses about why people do good things for others. Belong’s definition of radical kindness has grown out of: recent policy and practice in the UK designed to tackle segregation of social groups in British society, principally across barriers of race, faith and class; an ongoing debate about kindness and radical kindness in particular within the UK civil society, arts and cultural sectors; and social psychology theory on intergroup relations and cohesion (see below for theory).

Recent policy and practice to address cohesion and integration

In 2001, social unrest between different ethnic and faith groups in the northern towns of Bradford, Oldham, and Burnley drew attention to the fact that different groups in the UK were living ‘parallel lives’, i.e. occupying the same local areas but rarely coming into contact with each other in a way that fostered mutual understanding and relationships. Since then, successive UK governments have attempted to tackle issues of segregation via community cohesion and integration policies. The latest policy initiative (The Integrated Communities Action Plan 2019, Integrated Communities Strategy Green Paper 2018) provided modest funding from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG, now the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC)) to support, amongst other things, the roll-out of cohesion and integration programmes in five local areas (Blackburn with Darwen, Bradford, Peterborough, Walsall, and Waltham Forest).

Each local authority developed strategies and plans that were ‘place-based’ i.e. tailored to address specific local challenges to cohesion and integration.2 All of the programmes shared core characteristics including a strong focus on embedding social mixing (bringing individuals and groups together across differences through, for example, schools linking programmes). As part of our Beyond Us and Them research, we have worked closely with four of these Integration Areas (Blackburn with Darwen, Bradford, Walsall and Waltham Forest) and also Calderdale Council, which, though not one of the Integration Areas, has prioritised ‘kindness’ and ‘resilience’ (key elements of cohesion). Our research shows that an investment in cohesion in these areas has paid off with all of them reporting higher levels of neighbourliness and active social engagement, and sustained inclusivity towards others over the course of the pandemic (Abrams et al. 2021b). At Belong, we believe that radical kindness sits at the heart of cohesion and integration work as it involves proactively reaching out across differences, tackling prejudices, separation and segregation, and building bonds with people from different ethnic, socio-economic, faith, and age groups.

An ongoing debate about kindness and radical kindness within the UK civil society, arts and cultural sector

The word kindness originates from the Old English noun cynd (nature, family, lineage, kin) and ‘encompasses notions of compassion, social justice, neighbourliness and respect for others’ (Broadwood 2012: 3). The word radical originates from the Old English word radicalis (forming the root, inherent). Taken together, these words indicate the deep-rooted need we have as humans for a sense of connection to and with others that can transcend our tendency to favour our own group (homophily). The concept of radical kindness has gained currency across different sectors and disciplines in recent years. It is often understood as a form of kindness that moves beyond situational, random, or relational acts of kindness and instead addresses the structural inequalities in our society (Santomero 2019). In the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS), radical kindness has been used in differing but intersecting ways for a number of years. For example, the Carnegie Trust UK defines radical kindness as a form of kindness that ‘demands institutional change’ and ‘requires a difference in the ways in which things are run and managed’ (Unwin 2018: 20). Similarly, the participatory arts organisation, People United, uses the term radical kindness to understand how ‘it is possible to create kinder and more compassionate places to live, learn and work’ (People United n.d.: 5). For People United, radical kindness is ‘strong, profound, brave and often challenging’ and ‘can lead to lasting change’ (People United n.d.: 5).

At Belong, our concept of radical kindness dialogues with those put forward by the Carnegie Trust UK and People United. We define radical kindness as a type of kindness that reaches out across differences and may involve some form of disruption, discomfort, or transformation. It is distinct from random and relational acts of kindness, which tend to be carried out towards those who people perceive as belonging to the same group as themselves. In contrast, radical kindness refers to those acts and activities that intentionally seek to build bridges across differences, develop solidarity and shared ground, and promote social connection between different groups and communities.

Stereotypes and prejudices can lead directly to discrimination and denial of rights, and can also help to perpetuate and justify inequalities at both personal and institutional levels. Radical kindness is about tackling prejudices and addressing the root causes of segregation. It encourages us to overcome affinity bias, which is defined as ‘the tendency to gravitate toward and develop relationships with people who are more like ourselves and share similar interests’ (Nalty 2016: 46), in order to actively and intentionally understand and support others who are different from us. In this way, radical kindness offers a powerful means of promoting cohesion and addressing underlying prejudice as it encourages positive and prosocial behaviours and attitudes towards those who people perceive as being different from themselves.

Theorising radical kindness

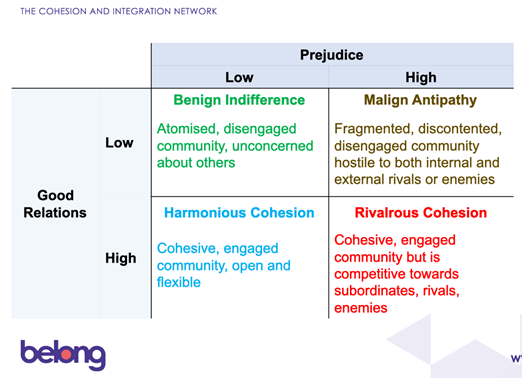

Kindness sits at the heart of cohesion and integration, and is crucial for creating more connected, more cohesive societies. In our Beyond Us and Them research project, we use a framework developed by the principal investigator, Professor Dominic Abrams, to understand how cohesion works in practice. This framework includes four component parts – harmonious cohesion, rivalrous cohesion, benign indifference and malign antipathy – that explain how differing levels of connection and social mixing between people in communities can impact cohesion at local levels (see Figure 1). Applying this framework here can help us to understand how and why creating the conditions for radical kindness to thrive in our communities is crucial for helping us to achieve a state of harmonious cohesion.

Figure 1: Forms of cohesion

Communities that get along well with each other should not necessarily be viewed as existing on the opposite end of the continuum to communities with higher levels of prejudice. In fact, as Figure 1 shows, in areas where people are engaged with the community but feel competitive towards out groups, rivalrous cohesion may emerge. In areas where people are living in the same places but do not care much about each other, benign indifference may emerge. This means that people are not in conflict, but they do not necessarily care about each other. This state of indifference leaves people and communities feeling disconnected and atomised. To avoid this and achieve a state of harmonious cohesion, where people are building bridges and making connections across differences, we need to tackle prejudice and build good relations with and between in-groups and out-groups. Radical kindness is crucial for achieving harmonious cohesion. Unlike other forms of kindness, which are often directed towards those we already know, love, or have obligations towards, radical kindness encourages us to do the bridging work of supporting and showing solidarity to those who are different from us and who face struggles that may not be familiar to us within our own lived experiences.

What is so radical about radical kindness?

Despite the current popularity of the concept of radical kindness, a number of objections arose to it over the course of our research. Some participants in our focus groups argued that the concept of kindness might place too much onus on individuals to act, rather than on the state to provide support to those in need. Others were uncertain about the value of the word radical, questioning whether it exceptionalises everyday acts of kindness that people see as ordinary and therefore unremarkable. They also wondered whether the concept focused too much attention on the doer, thereby creating an unequal exchange, undermining the potential for equality between the giver and the receiver. Finally, some felt that the term might only appeal to a narrow cross section of the population, particularly those with a liberal, left-leaning agenda and therefore potentially alienate others.

These misgivings encouraged us to think deeply and critically about the concept of radical kindness for Belong. In the end, we concluded that the value in radical kindness as a concept is because it encourages us to move beyond the dangers of commercialisation and popularisation (often considered to be inherent in the idea of random acts of kindness) into something more transformational, deep-rooted and longer-lasting. Radical kindness is not ordinary or routinised precisely because it forces us to question our actions, viewpoints and biases, and take an active step to reach out across differences and show kindness to those whose backgrounds and experiences are not the same as our own. Radical kindness recognises that people are not always equal, but that differences should be valued, and that equality of status in relationships can bring social, psychological, and material benefits to the receiver as well as the giver. Radical kindness foregrounds the valuable knowledge and lived experience that both the giver and the receiver bring to the encounter, whilst recognising that this will not be enough on its own to overturn structural inequalities. Above all, being radically kind can be transformational because it allows us to challenge limiting perceptions of ourselves and others, and creates the conditions for greater cohesion in our interpersonal relationships, communities, neighbourhoods, workplaces and societies. We also noted that the ordinary people and communities that shared their inspiring stories of bridging over the course of the pandemic were enthusiastic and positive about the term and embraced it as a concept and in all of its many practical applications.

"Radical kindness refers to those acts and activities that intentionally seek to build bridges across differences, develop solidarity and shared ground, and promote social connection between different groups and communities."

What are the barriers to radical kindness?

One of the main aims of this research is to detail the conditions that need to be in place for radical kindness to thrive. However, in order to be able to do this, we needed first to understand the barriers that prevent people from being able to engage in acts of kindness that involve reaching out across differences and promoting connections between groups and communities. In the process of our research, we came across three main barriers, which are discussed in more detail below.

Barrier 1: Structures and systems

One of the main barriers to radical kindness is the extent to which existing structures and systems in society make it difficult for us to be kind, (or indeed, actively incentivise us to be unkind,) or favour individualism over collectivism. In their landmark report, ‘The COVID Decade’, the British Academy argues that the UK’s commitment to a decade of austerity policies prior to the pandemic has had a significant impact on social and community connectedness and resilience (2021: 66). Substantial cuts to local authority budgets and local services has led to the sometimes permanent closure of civic institutions and spaces (e.g. libraries, community centres) that provided opportunities for social mixing and community engagement. It has also diminished the ‘capacity of local authorities to work with their communities […], due to reductions in local support officers and community development teams’ (The British Academy, 2021: 66). Though the COVID-19 pandemic revitalised volunteering and mutual aid, the British Academy reports that levels of volunteering had declined prior to the pandemic and that many local areas faced diminished levels of community resilience due to austerity policies. In some areas, these effects will have worsened due to the pandemic, which has further stretched local authority budgets and limited opportunities for social mixing in person.

Our current structures and systems often discourage mixing between people from different social classes, ethnicities, faiths, ages, genders, and abilities. According to the British Integration Survey, in 2019, 44% of British people reported that none of the contacts they spend time with socially are of a different ethnic background to them (The Challenge: 5). Low levels of social mixing between groups are compounded by factors such as segregated housing and segregated schools, and have been exacerbated by Covid-19 restrictions on social interaction and movement. Since the pandemic, many people have spent much more time at home, including working from home, and in their immediate locality, and therefore have not had the opportunity to mix with people from different groups in their area, workplace or at cultural and social events.

Barrier 2: Distrust

Distrust is a major barrier to radical kindness taking root in relations between individuals, and between individuals and the state. Our Beyond Us and Them research shows that levels of trust between individuals and the state, and individuals and other citizens, function as a clear indicator of how connected and cohesive a local area is (Abrams et al. 2020; Abrams et al. 2021b). In areas that had invested in social cohesion programmes prior to the pandemic, levels of trust in others and in government remained consistently higher than in other parts of the UK (Abrams et al. 2020 Abrams et al. 2021b).

Many of the participants involved in the focus groups for this project stated that they felt that distrust between different groups prevented kindness from forming in interpersonal and intergroup relationships. This distrust could stem from a limited understanding of different people and communities, a lack of confidence to reach across divides, or limited opportunities for social mixing.

A lack of trust between individuals/communities and local, civic and national institutions can also function as a barrier to radical kindness. Some groups and communities may feel mistrusting of institutions like local and national government, the police, or local health authorities, because of factors such as historical abuses of power, community tensions, segregation, or misinformation. Furthermore, fragmentation between different statutory, voluntary, community, and faith organisations and services can hinder efforts to bring people together and tackle mistrust/misinformation.

Barrier 3: Opportunities for individual and community agency and empowerment

Radical kindness is impeded when there are limited opportunities available for individuals and groups to feel empowered within their communities and lives. Research suggests that kindness thrives when individuals and groups feel they have agency over their lives and decisions, and feel empowered to enact positive changes in their communities (British Red Cross 2017). During the coronavirus pandemic, local people came together to show kindness, solidarity, and support to those in need around them. In order to harness the power of that kindness and the increased social engagement, local people need to feel empowered to effect longer term change in their environment.

What are the conditions that need to be in place for radical kindness to take root?

Radical kindness flourishes in places where the barriers are minimised, where opportunities for connecting across difference thrive, and where discrimination and structural inequalities are acknowledged and challenged. In order for strong bridging and social connection to occur, we need to tackle the underlying conditions that work against radical kindness such as inequalities, prejudice, and discrimination. Without also addressing inequality, there is a danger that radical kindness just on its own may lose its ability to transform relations between people and groups for the longer term. In order for change to take place, we need to tackle both the underlying conditions that lead to the segregation and separation of people, groups and communities, and the relationships between groups and communities (radical kindness). If we only address the conditions, then it is unlikely relations will improve, and if we only address relations, then eventually people may become cynical and resigned about the potential for longer-term change.

This section of the paper sets out some examples of actions, initiatives, programmes, and approaches that have helped to create the conditions for radical kindness to thrive in local communities. We draw on case studies and best practice examples from community, business, and volunteer organisations, and from the social cohesion investment areas, highlighting work carried out with their MHCLG / DLUHC Integration Area programme funding to encourage social mixing, tackle prejudice and discrimination, and build trust between individuals and between individuals and the state. The approaches adopted by these organisations and local authorities are shot through with an awareness of how structural inequalities and discrimination can prevent people from accessing resources or experiencing the same level of rights. Individually and collectively, they have attempted to understand the reasons why inequalities and discrimination exist and have taken steps to remedy them in their localities, workplaces and communities.

The examples below cohere around three key pillars of people, place, and knowledge. The approaches adopted by our partners show that place matters and that strategies to address social cohesion will need to be interpreted differently in different places. Local people are key to responding to local challenges as they possess the crucial specialist knowledge that helps create the conditions for kindness to take place.

Pillar 1: Place

Radical kindness is more likely to thrive in places where good relationships and cross-sectoral partnerships between government, business, and the voluntary and community sector are established. Our research has shown that during the coronavirus pandemic those local authorities that worked collaboratively across sectors found it easier to mobilise and support the needs of their local residents (Abrams et al. 2021). In Calderdale, for example, the council implemented cross-sectoral approaches in their response to the pandemic. Calderdale Council worked with the local mosque in Halifax to set up a community fridge where residents could bring surplus food to give to those in need during the pandemic. The community fridge brought together members of the white community and the Muslim community and worked to build trust and bonds between the two groups. The council also helped Jan Lymer set up Calder Community Cares and provided food delivery services and emotional and practical support to other residents in need.

Over the course of the pandemic, trust in national government was low whereas trust in local government tended to be higher. In the six local authority areas we surveyed, levels of trust were stable from May 2020 to June 2021 and were consistently higher than levels of trust in the UK government and in our control group (Abrams et al. 2021a). This is, in part, due to the strength of the programmes they set up prior to the pandemic and also because of approaches and initiatives that were put in place during the pandemic to tackle distrust between individuals, and between individuals and the state. In Walsall, at the beginning of the first lockdown in March 2020, the Walsall for All team approached faith and community leaders across the borough to video record the ‘Stay at Home’ message in their native languages. All of the recordings were then compiled into a 2-minute video representing around 17 different languages. This provided an opportunity for residents to hear from local people and to understand the importance of staying home in order to protect the NHS and save lives. The video was seen almost 6000 times on Facebook and was shared by various statutory services, NHS trusts, community groups and even residents themselves, helping to amplify the key messages as far as possible to ensure wide reach and engagement. This strategy is an example of an approach taken by a local authority to tackle misinformation and build a more trusting relationship between individuals and the state.

Pillar 2: People

Contact theory suggests that social mixing is one of the most effective ways of tackling prejudice and distrust between individuals and groups. Social mixing programmes are most effective when overseen by a trusted, legitimate source (such as a charity or faith organisation) and when those involved in designing and delivering programmes are representative of the diversity of the local area (Scott et al. 2020: 29). This helps to put participants at ease, improves the effectiveness of relationship building, and ensures that a plurality of groups and identities feel welcomed (Scott et al. 2020: 29).

During the pandemic, our partners in the six local authorities and in the volunteering and community sectors worked collaboratively with other local organisations to create opportunities for people to mix in a socially distanced way with others who were different from them. For example, Bradford City Council’s ‘Community Create Celebrate’ project shifted from in-person events that brought people together using cooking and dancing to an online mode of delivery. Using innovative ways to reach out to people at home, the council encouraged residents to grow plants and vegetables, cook with their children, learn about different cultures through food, and connect with each other by sharing photos of meals and vegetable-growing in a bespoke Facebook group. ‘The Community Makes Us’ project by The Jo Cox Foundation attempted to counteract division and divisiveness, and tackle the feelings of loneliness and isolation that had been exacerbated by multiple lockdowns, by bringing people together in online forums. From November 2020 to March 2021, seven groups of almost fifty individuals from Batley and Spen took part in weekly online “community conversations” led by experienced facilitators.

In addition to bringing people together from different backgrounds, it is crucial that organisations engage and work collaboratively with underrepresented groups and communities. Using participatory approaches can help to tackle inequalities and can allow space for more egalitarianism and reciprocity to emerge. Research on intergroup relations shows ‘that great progress is made when participants hold each other in mutual respect and interact with equal status’, but still acknowledge the structural inequalities that may affect them in different ways (Scott et al. 2020: 28). One way of achieving this (and of moving away from models of kindness that can appear patronising and condescending) is ensuring that there are structures and programmes in place that empower underrepresented and under-voiced groups and communities in decision-making processes. One example is Walsall’s UNICEF Rights Respecting Schools programme, which enabled local schools to employ rights-based approaches with young people. This had a demonstrable impact on integration in some schools as young people felt included and respected. Five secondary schools were supported by Walsall for All to join the programme and achieve their Bronze accreditation. The programme gave schools a pathway to teach structural inequalities and human rights to young people and to promote greater inclusivity and participation within the classroom environment.

Arts, culture, and sports programmes provide ways to address inequalities and create spaces where people can meet on an equal basis. Organisations like People United have long argued that the arts are a superconductor for kindness (Jo Broadwood, 2012; People United n.d.). Their research, together with that of others, shows that the arts and culture can increase empathy and compassion, and develop meaningful connections between people from different backgrounds. Our own research has shown that participation in sport and physical activity programmes can lead to greater cohesion and integration in local areas, and can help to tackle prejudices (Scott et al. 2020: 25).

During the pandemic, many of our partner organisations spoke at length of the value of the arts for tackling isolation and helping local people feel connected. Odd Arts, a local arts organisation in Manchester, recognised the power of the arts for helping people connect despite strict physical distancing measures. They sent out creative packs for people to do at home during lockdown, and arranged creative ‘door knock’ sessions where some of their team would deliver drama workshops on people’s doorstops to inspire happiness, joy and connection. Speaking on behalf of Odd Arts, Rebecca Friel stated:

“It’s just something that we’re really proud of because people who are facing multiple barriers and that might not be able to - you know - make it to The Powerhouse where we’re based can still access [our services] [...] They’ve been really nice to do.”

Pillar 3: Knowledge

Radical kindness is about forming and developing relationships across difference that prioritise and value the knowledge of the receiver as much as the giver, and that allow people to come together on an equal footing. It therefore follows that radical kindness will thrive in situations and environments where the specialist knowledge of local people and local communities is valued. In our focus group sessions, many participants spoke about the importance of using trusted local interlocutors to facilitate bridging activities and set up opportunities for meaningful interaction. This approach is particularly important for supporting community-led responses in times of crisis, rather than imposing top-down models that do not draw on local knowledge. In Waltham Forest, the council set up the Connecting Communities programme to bring together different faith communities (Jewish, Muslim, Christian) to share learnings and best practice around the Covid-19 pandemic. This programme tackled prejudices, created bridges, and empowered individuals to share knowledge and help others in the community.

Many of our partners have worked hard to ensure their leadership and senior management teams are diverse and inclusive and reflect the demographics of their communities. Diverse leadership is crucial for ensuring that different voices and perspectives are valued and listened to, and that individuals and communities feel represented at senior levels. Leaders need to be able to express empathy and compassion, and be able to listen actively to the people they represent. This matters across all sectors including the business sector. For example, Beaverbrooks is a family-owned jeweller based in the UK. The managing director, Anna Blackburn, is one of a handful of female leaders in UK retail. Beaverbrooks has a predominantly female workforce and has long championed an approach to flexible working that focuses on individuals’ circumstances rather than policies. Long before the Covid-19 pandemic, employers had the option to work from home and flexible working patterns have regularly been put in place for people returning from maternity/paternity leave.

Sometimes, organisations and institutions need to develop strategies that actively address existing structural inequalities in society. An example here is the financial tech institution Algbra, which has been created to address issues of financial exclusion, particularly amongst minority communities in the UK and abroad. Core to its business model is engaging the underrepresented and the underserved that are not typically well-served with financial services. Algbra places the voices of these communities at the heart of the work that they do. Speaking about Algbra’s mission, Nizam Uddin said:

“How do we ensure that everyone in our society feels included and is included? And sometimes you have to create vehicles and institutions to try and ameliorate existing fault lines of challenges. We feel there are far too many people who are not maximising the financial system as they could and we are here to change that.”

What can we learn from these areas and organisations?

The UK is one of the most geographically unequal countries in Europe. The reasons for this are complex and historical and it will take time to shift the deep-rooted and longstanding structural inequalities that have been thrown into stark focus by the uneven impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on different social groups and regions. The government’s recently published Levelling Up agenda (Levelling Up the United Kingdom 2022) has emphasised the importance of rebalancing the economy between the north and the south of the country and pays attention to post-industrial towns and coastal resorts, which have suffered decades of decline.

Both our own research and that of others shows that the current circumstances have the potential to unite and fragment sections of British society along existing and emerging fault lines and to bring to the fore inequalities related to ethnicity, faith, disability, intergenerational differences, and socio-economic divides (PHE 2020; Juan-Torres et al. 2020; Talk/together 2021, The British Academy 2021; Duffy et al. 2021). The findings from our Beyond Us and Them research indicate that areas that had invested in social cohesion prior to the pandemic were seeing higher levels of neighbourliness, increased social engagement and higher levels of trust at local and national levels (Abrams et al. 2020; Abrams et al. 2021b). This suggests that investing in approaches that centre cohesion can help to build kinder, fairer, more inclusive communities, workplaces, communities and neighbourhoods.

The organisations and areas that have taken part in our research have already embraced a philosophy and approach that has put local communities in the driving seat of creating more empowered, connected and kinder places. There is much that can be learnt from their approaches. Their work shows us that social cohesion needs to include an emphasis on high quality social mixing and tackling barriers to the inclusion of underrepresented groups and minority communities (including proactively addressing prejudice, hate crime and discrimination). The best schemes tend to be those that are co-produced between local government and local communities and engage widely across sectors to deliver on outcomes that benefit local people.

As we begin to emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic and rebuild our communities, we believe that radical kindness will be more important than ever. The conditions we have outlined in this paper will be invaluable for harnessing the kindness that has flourished during the pandemic and building more equal, cohesive societies that are able to weather future crises and where people from different backgrounds feel they belong.

References

Abrams, Dominic and Michael A. Hogg, Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes (London: Routledge, 2006)

Abrams, Dominic, et al., “Beyond Us and Them: Societal Cohesion in Britain Through Eighteen Months of Covid-19”, (2021a), https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/resources/beyond-us-and-them-societal-cohesion-in-britain-through-eighteen-months-of-covid-19/

Abrams, Dominic, et al., “Community, Connection and Cohesion during Covid-19: Beyond Us and Them Report”, (2021b), https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/resources/community-connection-cohesion-report/

Abrams, Dominic, et al., “The Social Cohesion Investment: Local Areas that Invested in Social Cohesion Programmes are Faring Better in the Midst of the Covid-19 Pandemic”, (2020), https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/resources/the-social-cohesion-investment-local-areas-that-invested-in-social-cohesion-programmes-are-faring-better-in-the-midst-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Broadwood, Jo, “Arts and Kindness”, (People United Publishing, 2012), https://peopleunited.org.uk/resources/

Broadwood Jo, et al., “Beyond Us and Them: Policy and Practice for Strengthening Social Cohesion in Local Areas”, (2021), https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/resources/beyond-us-and-them-policy-and-practice-for-strengthening-social-cohesion-in-local-areas/

Duffy, Bobby et al., “Unequal Britain: Attitudes to Inequalities after Covid-19”, The Policy Institute KCL (2021), https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/unequal-britain.pdf

Hodsone, Gordon and Miles Hewstone, eds., Advances in Intergroup Contact (London: Psychology Press, 2013)

Juan-Torres, Míriam et al., “Britain’s Choice: Common Ground and Division in 2020s Britain” (More in Common, 2020), https://www.britainschoice.uk/media/ecrevsbt/0917-mic-uk-britain-s-choice_report_dec01.pdf

“Levelling Up the United Kingdom” (2022), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom.

Nalty, Kathleen, “Strategies for Confronting Unconscious Bias”, The Colorado Lawyer, 45(5) (2016), 45-52

People United, “Taking Care: The Art of Kindness”, (People United Publishing, n.d.), https://peopleunited.org.uk/resources/

Public Health England. “Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19,” (Crown, 2020), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf

Santomero, Angela, Radical Kindness: The Life-Changing Power of Giving and Receiving (Harper Collins, 2019)

Scott, Ralph et al., “The Power of Sport: Guidance on Strengthening Cohesion and Integration through Sport”, Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network (2020), https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Belong_PowerofSport_V6.pdf

Talk/together, “Our Chance to Reconnect: Final Report of the Talk/together Project”, 2021, https://together.org.uk/Our-Chance-to-Reconnect.pdf

The British Academy, “The COVID Decade: Understanding the Long-term Societal Impacts of COVID-19”, (The British Academy, 2021), https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/3238/COVID-decade-understanding-long-term-societal-impacts-COVID-19.pdf

Unwin, Julia, “Kindness, Emotions and Human Relationships: The Blind Spot in Public Policy”, Carnegie UK Trust (2018), https://d1ssu070pg2v9i.cloudfront.net/pex/carnegie_uk_trust/2018/11/13152200/LOW-RES-3729-Kindness-Public-Policy3.pdf

Authors' bios:

Kaya Davies Hayon is Research and Development Manager at Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network. She holds a PhD in cultural studies from the University of Manchester and worked in academia for a number of years before joining Belong. Kaya’s research focused on social integration and representational politics, particularly as they relate to film and visual media. At Belong, Kaya holds responsibility for leading a number of the organisation’s research projects and for developing research outcomes.

Jo Broadwood has been Chief Executive Officer of Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network since February 2019. Previously, Jo was CEO of StreetDoctors where she grew a UK wide healthcare volunteering movement advocating for a public health approach to address youth violence. Jo has worked in a number of senior leadership positions in the third sector leading on the design and development of a series of award winning programmes to tackle gangs and territorialism, reduce prejudice and hatred and build social peace. Jo was a Community Cohesion advisor for the Department of Communities and Local Government supporting local areas to reduce community tensions and improve good relations. Her background is in conflict transformation and she has worked as a practitioner in the UK and internationally.

Christine Cox has committed her career to conflict transformation and empowerment of communities to move beyond trauma and towards a healthier future. She has designed and facilitated multiple ‘on the ground’ programmes in countries affected by conflict as they seek to rebuild and create a more cohesive society, including Central Asia, Georgia, Bangladesh, Kenya and the Somali refugee camp Dadaab. In addition, Christine has worked within the UK (Leeds, Manchester, Burnley, Bradford, Rochdale, Oldham, Peckham and Southwark in London) with young people and wider communities in multiple areas facing issues including deprivation, limited resources, territory and gang conflict, community division and increased threat of recruitment by extremist organisations. Christine has also set up community radio stations in the UK, Ninotsminda and Marneuli (Georgia). She has a Post-Graduate Diploma from Cambridge University on Child and Adolescent Psychotherapeutic Development.

Artist bio:

Elise Florentino is a young Caribbean and Spanish artist. Elise graduated in illustration in Oviedo School of Arts and studied Fine Arts in Altos De Chavón School of Design, an art school affiliated to Parsons in the Dominican Republic. Her work always analyzes what it is like to be European, Latin American and Afro at the same time. For Elise the world has many points of view and she wants to know how all of them work, always using empathy to create colorful and baroque artworks with a large amount of lines and textures. She has learned many techniques and ways of creating throughout her life and is not afraid of using them all, that is why you can find her working on painting, sculpture, photography, video, drawing, or animation. A versatile and productive child, says her mom. Born in 1998, you can find more about her on instagram : @indiespice___. Yes, the name is in honor of the Spice Girls and California Bands like Fidlar or Bleached.

Art description:

Radical Kindness for me is a way of life. Some people do not get why I always forgive, but I perceive forgiveness as a way of being nice not only to the person I forgive, but to make the world a better place. We do not know how the future will be, we do not even know about how people are doing in their lives. Creating warm places for everybody is the duty of empaths. Coming to the world, being alive and being able to feel the way you do when you have a lot of empathy is a way of giving a big contrast to all the wars, disasters and heartbreaks that lives among us. As the world is cruel and dangerous, there must be people around that gives hugs to the proud little lions. For me the lion symbology means being self centered and self efficent, the king of the jungle does not need any of us. But even the strongest human is vulnerable and as I said in the beginning, life can be changed in one second. Helping others is amazing and the level of emotional connection that you can reach listening, walking and going along with others is amazing. My message with this illustration is that we all should be there, we have to see when somebody needs us in any situation, we have to make the world warm and understand our siblings.