Introduction

It seems that we live in a time of polarisation. The most salient areas of public debate are characterised by deep division on, for example, immigration, restrictions implemented to reduce transmission of covid, vaccination, membership of the European Union. In this context, the assertion wheeled out by both the political left and the right that “there’s more which unites us than divides us” can sound like naive and ill-founded optimism.

But polarisation is also a product of particular approaches to public debate, and a choice to focus on points of difference rather than shared concerns and experience. The mainstream media tends toward areas of disagreement and conflict, which are often exacerbated by the binary choices presented to us in referendums and elections (especially under winner-takes-all electoral systems such as those in the US and UK).

This paper develops the argument that public debate at its most polarised focuses on attitudes toward specific political programmes or policy choices, rather than the values that underpin our political convictions. Whereas our societies may be deeply polarised around attitudes towards, for example, immigration, the values that underlie these attitudes may be more closely aligned. Building on a body of recent research on the social psychology of values, this paper develops the argument that dialogue across points of difference can evolve from a deepened appreciation of shared values, and that prejudice towards people who are seen as different can be reduced by recognising common value priorities. It highlights the empirical evidence for this perspective and outlines practical projects that have set out to build dialogue by starting with an appreciation of shared values.

Values

In this paper, I will use the concept of “values” as it is deployed by social psychologists — to mean the guiding principles we hold and which help to shape our attitudes and behaviours. In this sense, values are fundamental psychological constructs that are central to a person’s sense of who they are. As leading researchers in the field note:

“[P]art of the importance of these constructs derives from their abstract nature, which transcends specific situations and objects, enabling people to use values as markers of common, shared principles and ideals… This aspect makes socially shared values particularly intriguing as potential key binding factors that may facilitate social belongingness, shared norms, and positive intergroup and interpersonal relations.”1

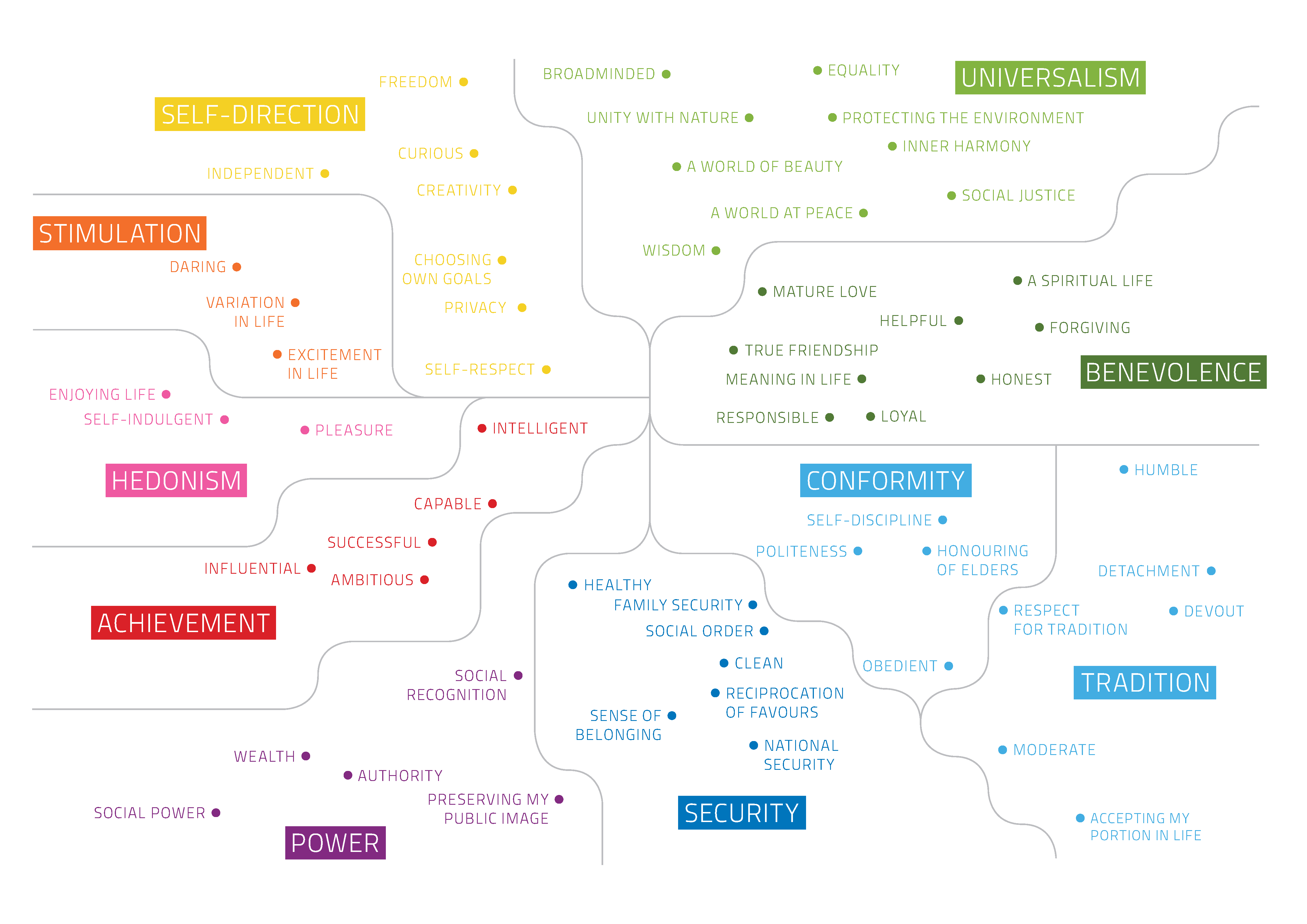

I will build, particularly, on the extensive body of empirical research related to a widely used model of values developed by the social psychologist Shalom Schwartz. This model comprises 58 values items – for example: “ambitious – hardworking, aspiring”; “broadminded – tolerant of different ideas and beliefs”; “clean – neat, tidy”; “obedient – dutiful, meeting obligations”; “pleasure – gratification of desires”.

Some of these value items are more easily prioritised simultaneously – a person, for example, who attaches importance to the value item “respect for tradition – preservation of time-honoured customs” is also likely to ascribe importance to “honouring of elders – showing respect”. Other items stand in psychological tension with one another– it is unlikely for a person to ascribe importance at the same point in time to both “respect for tradition – preservation of time-honoured customs“ and “choosing own goals – selecting own purposes” (though they may place a great deal of importance on each of these values at different times).

These compatibilities and tensions can be depicted spatially. Figure 1 presents data collected from approximately 64,000 survey respondents across 68 different countries, who were asked to rate the importance of each value item as a “guiding principle” in their life. Values items that are closer to one another in the “map” are more likely to be accorded similar importance by the same respondent; those distant from one another are unlikely to be accorded similar importance by the same respondent (see Figure 1).

Respondents differ in the importance that they place on different values items as “guiding principles” in their lives – for example, some will place particular importance on “respect for tradition” others will place particular importance on “choosing own goals”. However, the relationships between the value items (that is, the patterns of compatibility and tension) seem to be remarkably consistent across respondents.

Like all models, the Schwartz model has short-comings and blind spots (it hasn’t, to my knowledge, ever been tested on indigenous communities, for example). But, despite its limitations, it is useful because it makes empirically verifiable predictions about how values are strengthened, and how they interact with one another. I will show that an understanding of values is of profound importance to fostering dialogue between people who see themselves as different from one another, to uncovering shared identity, and to deepening commitment to environmental protection and social justice.

The Schwartz model identifies several higher-order groups of values, but this paper focuses on just two. I will call these “intrinsic” values and “extrinsic” values.2 These two groups are of particular relevance to people’s social and environmental concern, people’s motivation to express this concern through various forms of civic action, and people’s feelings of social connectedness.

Intrinsic values

Intrinsic values include values such as “responsibility”, “equality”, “social justice”, “helpfulness”, “protecting the environment”, “forgiveness” and “creativity”. These values lie in the Benevolence, Universalism, and Self-direction groups in Figure 1. As we’ve seen, these values, which are adjacent to one another in Figure 1, are related to one another, such that a person who attaches relatively high importance to any one of these values is likely to also attach relatively high importance to the others.

People who hold intrinsic values to be particularly important are found to be significantly more likely to express concern about social and environmental problems – both in the attitudes they hold, and the behaviours they adopt in awareness of these problems. People for whom these values are more important also tend to display lower “social dominance orientation” (SDO), a measure of the tendency to define one’s in-group as superior to out-groups. Higher SDO is associated with more nationalist, racist, or speciesist attitudes and behaviours.3

Almost everyone holds all these intrinsic values to be important at some level, though the relative importance they are accorded varies from person to person.

Extrinsic values

The second group of values relevant for our present purposes are extrinsic values. These include values such as “wealth”, “social recognition”, “social status”, “authority”, “popularity”, “influence” and “ambition”. The concept of values, as used in a social psychological context, is not limited to values that are typically thought of being “moral standards”.

As with intrinsic values, almost everyone holds extrinsic values to be important at some level. Nonetheless, some people place relatively great importance on “intrinsic” values; some on “extrinsic”. These differences, which may reflect durable or “dispositional” aspects of a person’s identity, arise as a result of a wide range of different influences including, for example, the way in which a person was brought up, the education they received, the values of their peer-group, and the wider socio-political context in which they live.

I highlight the socio-political context because it’s important and it often goes unseen. David Foster Wallace noticed that we each slip into these value-systems: “day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that's what you're doing.”4 Intuitive politicians recognise this, and use it to their advantage. They see their political programmes as being about more than promoting particular kinds of policy. Margaret Thatcher, a pioneering neoliberal and British prime minister, once commented that:

“…it isn’t that I set out on economic policies; it’s that I set out really to change the approach, and changing the economics is the means of changing that approach. If you change the approach you really are after the heart and soul of the nation. Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul.”5

Although she doesn’t invoke the construct of values as understood by social psychologists, she presumably means something similar when she refers to the “heart and soul”. Thatcher acknowledges that she aimed to use her political influence while in power (predominantly as wielded through economic policy change) to alter the values of UK citizens – that is, to shift these in a more extrinsically-oriented direction such that they better aligned with the broader political objectives of neoliberalism: emphasising the pursuit of individual self-interest, tolerance of widening inequality, celebration of wealth, and denigration of social institutions designed to support those in need.

Despite the effectiveness with which neoliberal thought has percolated social institutions across many countries, most people in most countries nonetheless attach significantly greater importance to intrinsic values than extrinsic values. Common Cause Foundation collated available data for populations in 89 countries. In 88 of these, an average citizen attached greater importance to intrinsic than extrinsic values.6 This tendency to prioritise intrinsic values also persists across different political orientations – we have found it to be true in both the US and UK regardless of whether a survey respondent self-identifies as socially or economically liberal or conservative.

This is not to blindly assert similarity across these groups, or to deny the reality of deep political polarisation. It is rather to suggest that prejudice often arises between groups because of different instantiations of compatible values. So, for example, an older English woman’s concern for the wellbeing of the young people in her community (an expression of intrinsic values) might be instantiated as a desire to ensure that young people are free to travel and work across Europe (a reason, she believes, for the UK to remain part of the European Union). Meanwhile her neighbour, an older man, shares this same concern for the future of the young people in his community, but this leads him to want to ensure that employment prospects are buoyant locally, and that local jobs aren’t taken by immigrant workers (a reason, he believes, for the UK to leave the European Union).

In this way, compatible value priorities, about which these two people could agree, have been captured by different political positions. These differences are then canalised further by a blunt democratic process (here a binary “in/out” referendum). The result is polarisation.

Figure 1:

Dimensional smallest space analysis: individual level value structure average across 68 countries. Redrawn by Minuteworks from Schwartz (2006) with permission.

The Values Perception Gap

But, what of people’s perceptions of others' values?

Research on people’s perceptions of their fellow citizens’ values (including Common Cause Foundation’s own research which has contributed significantly to the literature in this area) reveals that citizens across both the US and UK typically underestimate the importance that an imagined typical fellow citizen attaches to intrinsic values and overestimate the importance that this imagined person attaches to extrinsic values.

In the UK, for example, we found that 77% of respondents in a large and demographically representative survey held this skewed perception of their fellow citizens’ values. This “values perception gap” was found across demographics – it was encountered regardless of gender, age, political orientation, and geographic region.7 We have found in another UK study that it also persists regardless of how a survey participant voted in the 2016 referendum on leaving the European Union.8

The values perception gap may prove to be important, because people who hold this inaccurate perception of their fellow citizens’ values are also found to:

- feel significantly less positive about various forms of civic participation - joining meetings, voting, volunteering

- report lower feelings of responsibility for their communities, and be less likely to report fitting in with wider society

- express lower support for a range of social and environmental policies, including climate change, homelessness and inequality

- report lower wellbeing

Other studies have also found that people’s perceptions of the values held by members of an outgroup are important predictors of prejudice towards these groups.

Studies of this nature, while intriguing, do not demonstrate the nature of any causal connection between the values perception gap and these social outcomes. But they raise the possibility that these outcomes might be improved by either:

- conveying an understanding that a large proportion of one’s fellow citizens attach high importance to intrinsic values (or relatively low importance on extrinsic values); or

- conveying the understanding that members of an outgroup attach importance to intrinsic values (and relatively low importance on extrinsic values).

Recent experimental studies have begun to explore both possibilities. For example, Hanel and colleagues have shown that the way in which data about an outgroup’s values are presented has an impact on prejudice towards that group. In a recent study, participants were shown accurate data which was presented in ways that conveyed either an implicit understanding of similarity between the values of two different groups (UK citizens and Polish citizens), or an implicit understanding of difference. Those in the similarity condition reported lower prejudice towards people of the other nationality.9

Work by others also finds that prejudice towards Muslims and economic migrants is lower among people who believe that members of these two groups attach greater importance to intrinsic values10 and that a more accurate perception of compatriots’ values strengthens pro-environmental concern. 11

Origins of the Values Perception Gap

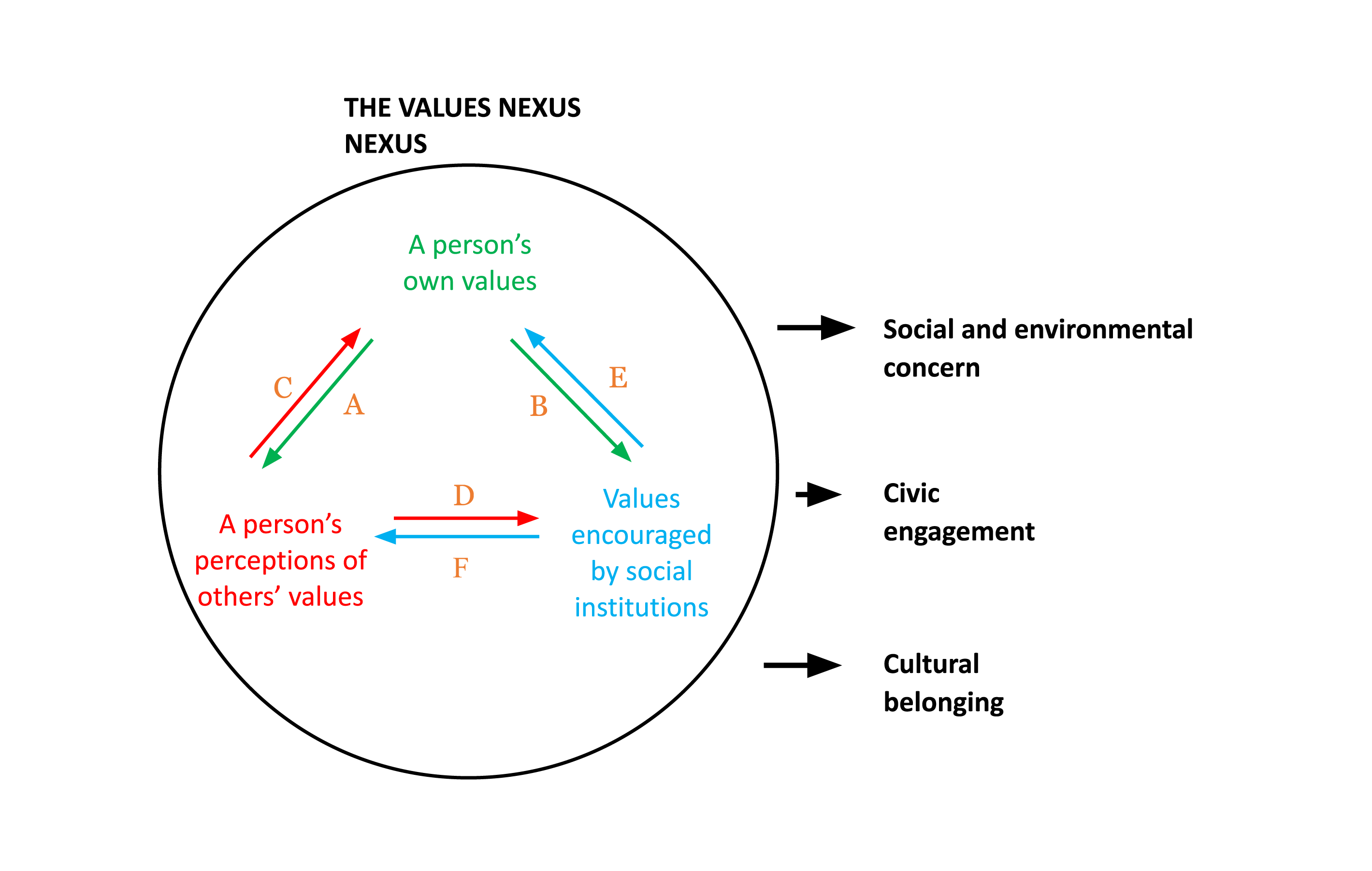

How might the values perception gap emerge and strengthen? This section will elaborate on some mechanisms by which this may plausibly happen, and will examine the relationship between three different, but interrelated factors:

- people’s own values,

- people’s perceptions of others’ values,

- values that are encouraged, perhaps very subtly, by social institutions (for example, media organisations; schools and universities; arts and cultural organisations; businesses; and government - executive, legislative and judicial).

As these three factors are likely to interact with one another, reference will be made to a ‘values-nexus’ - the complex interactions by which each of these factors is likely to both shape, and be shaped by, the other two (see Figure 2). Each of these three factors will be considered in turn.

People's own values

People will draw on their lived experience in forming their beliefs about a typical fellow citizen’s values. But their lived experience – the kind of people that they encounter and their perceptions of these people – will be shaped, in part, by decisions they make in light of their own values. People’s own values are likely to influence (among other things) the friends that they choose, the neighbourhoods in which they settle, the jobs they do, the TV stations they watch, the newspapers or blogs they read, and their leisure activities. Each of these life decisions will, in turn, impact the opportunities a person has to formulate his or her perceptions about their fellow citizens’ values. In sum, people’s commitment to particular values is likely to influence their perceptions of a typical fellow citizen’s values (see Arrow A in Figure 2).

People’s commitment to particular values is also likely to influence the shape of the social institutions with which they interact (see Arrow B in Figure 2). People’s values will influence their perceptions of the kind of society in which they would like to live – and therefore their beliefs about how social institutions should operate. Citizens play an important role in shaping social institutions – for example, as voters, customers, or volunteers. People’s values are predictive of their voting preferences and their purchasing decisions, their motivation to volunteer, and their commitment to various forms of civic engagement. Citizens’ values will therefore influence the way these institutions develop.

Clearly, the values held to be important by decision-makers with direct responsibility for these institutions (for example, elected politicians or business leaders) are likely to be still more influential in shaping how these organisations develop.

People’s perceptions of others’ values

People’s perceptions about a typical fellow citizen’s values are likely to contribute to deepening their own commitment to some values – and to weakening their commitment to others (see Arrow C in Figure 2).

A person’s perception of a typical fellow citizen’s values will influence their understanding of what is ‘normal’ or ‘acceptable’ behaviour, and is likely, by extension, to influence their behaviour (at least when this is observed by others). But a person’s behaviour is also known to influence his or her values. When I perceive myself behaving in a particular way, I’m likely to draw inferences (which may not be conscious) about what I value and may modify the importance that I attach to particular values accordingly.12 So, a person’s perception of what matters to others is likely to influence his or her behaviour, and accordingly, the importance that he or she attaches to particular values.

How will my perception of others’ values be shaped? My perceptions will be influenced, in ways that I may not be consciously aware, by both what fellow citizens say is important to them and what I infer about fellow citizens from the way I experience them behaving. So my perceptions of others’ values will be shaped by what I hear others say, and witness others doing.

For this reason, it could be significant that people don’t always bear testimony to the values they hold to be most important – either in what they say, or what they do. Indeed, it is known that people often speak and act as though they are more self-interested than is the case.13

People’s perceptions about other’s values are likely to contribute to shaping social institutions (see Arrow D in Figure 2). This influence will arise, in part, through public support for some types of social institutions. If most citizens believe that a typical fellow citizen is dishonest, this is likely to deepen public support for a social security system geared to catch ‘welfare cheats’ – even if this risks denying support to many who are deserving. If, on the other hand, most citizens believe that a typical fellow citizen is honest, this is likely to deepen public support for a social security system that is accepting of some abuse while ensuring that the majority of people, with genuine need, are able to access support in a straightforward way.

A decision-maker’s perceptions about a typical fellow citizen’s values are likely to have an immediate impact in shaping the institutions in which they have an involvement. Yet most people’s perceptions of others’ values are inaccurate, and it seems decision-makers are as likely to be susceptible to this misperception as anyone else. Indeed, it may be consistent with their political perspective to assume extrinsic values are more important to most citizens than is the case.

The values encouraged by social institutions

People’s experience of any social institution – for example, schools, shopping malls and television – will contribute to deepening their commitment to some values, and to weakening commitment to others (see Arrow E in Figure 2).

To the extent that institutions tend to encourage particular values, people’s experience of these institutions is likely to strengthen the importance they come to place on these values. Research finds that, over time, people learn to place importance on particular values as a result of their social experience.14 For example, studying law has been found to lead students to place greater importance on extrinsic values – perhaps because of the competitive nature of undergraduate law degrees.15 The influence of social institutions is also likely to operate at a national level. It is known that citizens in more economically de-regulated countries tend to attach relatively greater importance to extrinsic values, and lower importance to intrinsic values.16

People’s experience of any social institution will influence their beliefs about the values of a typical fellow citizen (see Arrow F in Figure 2).17 Where institutions have been designed with the expectation that people behave in line with particular values, behaviour associated with these values is more likely to be elicited. Think about what a social institution incentivises and rewards, what it measures, and what implicit assumptions it conveys about the way that most people behave. These characteristics contribute to creating and affirming people’s perspectives on human nature.18

Institutions encourage people to behave in particular ways. These patterns of behaviour convey an understanding of what motivates people and of the values that people hold to be important. If social institutions repeatedly elicit particular kinds of behaviour, then this is likely to shape wider perceptions of the values held to be important by a typical citizen.

So, for example, if social institutions are designed in ways that anticipate citizens will behave in predominantly self-interested ways, self-interested behaviour is more likely to be elicited, providing ‘social proof’ of the importance of extrinsic values.19 As one social psychologist writes:

“[T]he image of humans as self-interested leads to the creation of social institutions (e.g. work-places, schools, governments) in that image which, in turn, transforms that image into reality.”20

Citizens - particularly in liberal economies – are generally resistant to suggestions that there is any legitimate role for public institutions in shaping citizens’ values. But of course, whether acknowledged or not, public institutions do shape citizens’ values, and our perception of others’ values. To maintain the fiction that this is not the case is dangerous. The question that should preoccupy us is not whether this happens (it manifestly does) but rather how our values are changed, and what the consequences of this are.

Figure 2: The ‘values nexus’

A person’s own value priorities, a person’s perceptions of others’ values, and the values encouraged by social institutions can be expected to interact with one another. For example, a person’s own values are likely to influence the type of people with whom she becomes familiar (the friends that she chooses, the TV stations that she watches, etc.) and will also therefore influence this person’s perceptions about a typical fellow citizen – including a typical fellow citizen’s values (Arrow A). Social institutions will be shaped in part by people’s own values (for example, through the preferences that people express as decision-makers, voters or consumers) (Arrow B). A person’s perceptions of social norms – the values that most other people are seen to prioritise – will likely affect the values that this person prioritises (Arrow C). Social institutions are also likely to be influenced by people’s perceptions of others’ values. For example, perceptions that most people prioritise economic self-interest above honesty will lead to the creation of institutions that anticipate widespread cheating (an anticipation that will be held by both decision-makers in charge of an institution, and the wider public who may vote these decision-makers into their roles) (Arrow D). Social institutions are likely to influence citizens’ values (think, for example, of the role of government in “changing the heart and soul” as mentioned in Section 2.2 above). (Arrow E). Finally, social institutions are likely to influence people’s perceptions of others’ values through the expectations that they create about how citizens will behave. For example, do these institutions assume honesty and trustworthiness on the part of their stakeholders? (Arrow F). Interaction between these elements of the values nexus will therefore contribute to determining levels of public concern about social and environmental problems, commitment to civic engagement and feelings of cultural belonging. They will also contribute to determining the level of ambition shown by business, government and the third sector in pursuit of these outcomes.

Closing the values-perception gap?

In Section 2, I presented evidence that healing social division, deepening connection to community, inspiring civic participation, and building durable commitment to ambitious social and environmental change are processes rooted in intrinsic values. Further, I have suggested that – despite decades of living with social institutions that foreground and celebrate psychologically opposing extrinsic values – our commitment to these intrinsic values, though shaken, has proved remarkably durable. This commitment to intrinsic values cuts across demographic divides. It is found among men, women, young people, older people, people who self-identify as conservative and those who see themselves as liberal, and (in the UK) “Brexiteers” and “Remainers”.

In Sections 3 and 4, I have argued that, despite our quiet personal commitment to intrinsic values, we often fail to communicate or act in ways that would provide testimony, visible to others, of the importance that we place on these values, and that as a result of this we do not fully appreciate one another’s commitment to them. We have been conditioned to believe that our fellow citizens attach greater importance to extrinsic values, and lower importance to intrinsic values, than is actually the case. This cruel misperception holds us back from co-creating the better world that most of us want. How might it be dismantled?

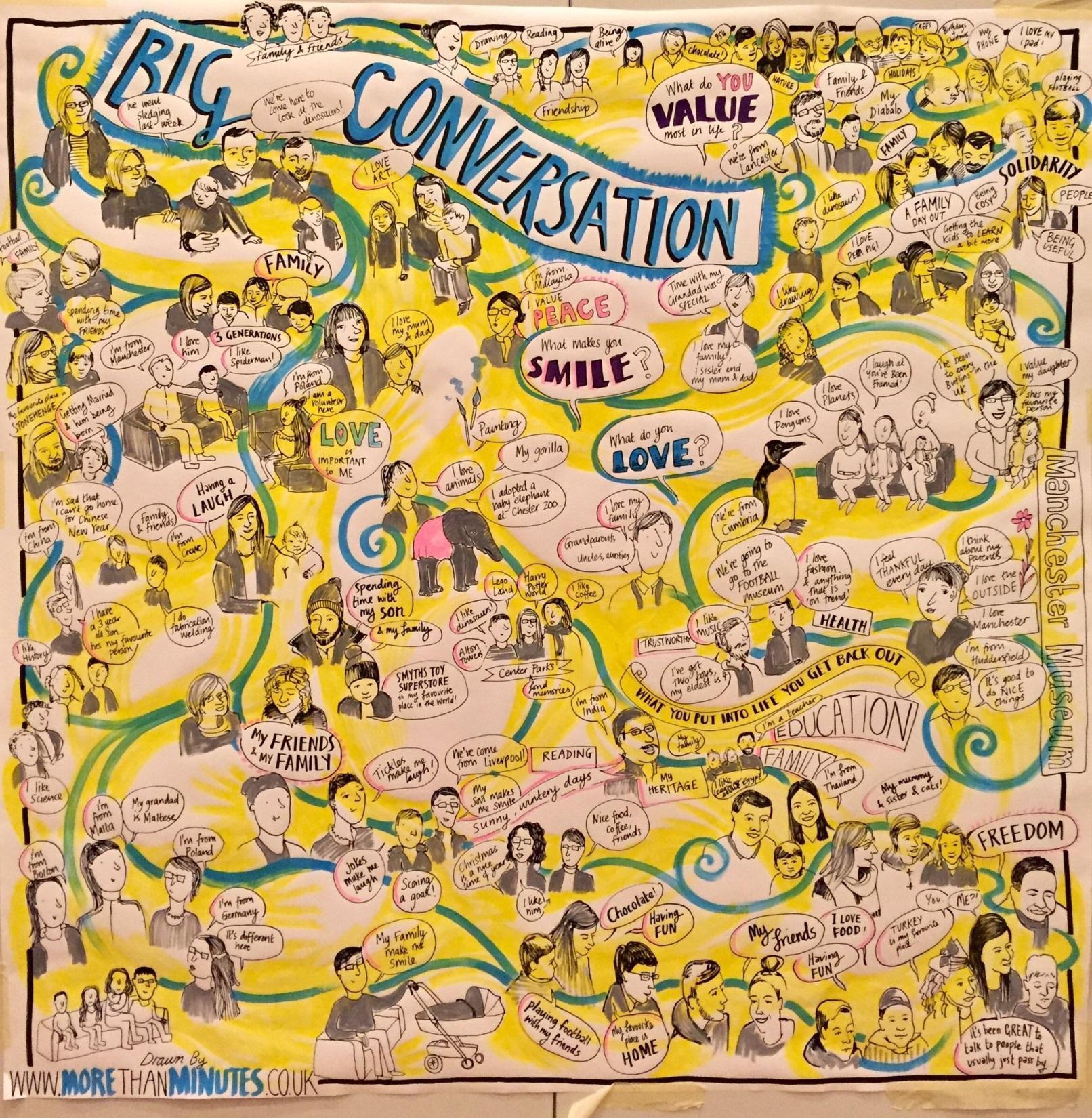

This section presents a case study that Common Cause Foundation conducted in partnership with a large Museum in Manchester, UK, with the aim of helping to close the values perception gap.21

Data and its shortcomings

The most obvious approach to closing the values perception gap might be to share data on other people’s values. Certainly this has a place; there is experimental evidence that simply showing people data on others’ values can help to reduce prejudice towards out-groups, although it is not known how durable such effects might be.22 Common Cause Foundation has itself experimented with this approach. We surveyed large and demographically representative samples of citizens from across the Greater Manchester city region, asking them to complete a values survey twice – first for themselves, and then for an imagined typical fellow citizen of the city. The survey results revealed that while a large majority of citizens (85%) prioritise intrinsic values, a large majority (75%) underestimate the importance of these values to their fellow citizens. These survey results were picked up by local media and discussed widely, including by the city’s political leaders. Working with Manchester Museum we developed a gallery display presenting the results of this survey.

Our expectations for this approach were low: there is a large body of experimental evidence pointing to the inadequacy of information in promoting attitudinal or behavioural change. The museum itself was at the forefront of changes in the museums sector, moving away from static presentation of information and towards the creation of more immersive learning and engagement opportunities. Our main interest, then, was in piloting less didactic and more experiential approaches to deepening visitors’ appreciation of the importance that their fellow citizens placed on intrinsic values.

Showing not telling

As a second step in this project, we identified areas of activity within the museum which testified particularly to the importance that most Greater Manchester citizens place on intrinsic values. For example, the museum hosted a roster of 200 volunteers who gave their time freely to the organisation, often on a weekly basis. A typical visitor, however, may have remained almost entirely oblivious to this testimony to volunteership. Such a visitor may well have encountered a few volunteers over the course of her visit but would probably have remained unaware of whether she was interacting with volunteers or paid members of the museum’s staff.

We sought to change this, and to demonstrate commitment to volunteership. We ran a series of workshops for museum volunteers, facilitating participants to share and explore their personal motivations for volunteering. We then celebrated these motivations, using volunteers’ own language, in a series of posters which were put in prominent locations inside and outside the museum (see Figure 3). These posters encouraged visitors to ask volunteers about their reasons for volunteering.

Concurrent with producing these posters, we also made changes to the volunteer induction process, encouraging volunteers to engage visitors in conversation about their motivations for volunteering. We revised the Volunteer Handbook to include an invitation for volunteers to commit to becoming an advocate for volunteering and sharing with visitors their own motivations for volunteering. Volunteers were also invited to wear button badges reading “Ask me why I volunteer”. Working in this way we attempted to encourage volunteers to open up to visitors about their motivations to volunteer (which we found, usually, to be rooted in intrinsic values) and to encourage visitors to initiate conversations with volunteers, exploring these motivations.

Experiential approaches

One implication of research on the values perception gap is that by encouraging citizens to explore with one another their values will, on average, lead them to the recognition that they each prioritise intrinsic values. Such an approach is predicted to be especially helpful in closing the values perception gap when this exploration of values is facilitated between people from different demographics, or with different political perspectives.

We trialled such an approach at Manchester Museum. Museum volunteers recruited visitors from the galleries to participate in a conversation with another. This conversation was lightly facilitated to encourage participants – strangers who hadn’t previously met – to reflect on what mattered to them most in life and was run as a relay: as the conversation drew to a close, one of the participants would leave, to be replaced by another. We enlisted a graphic artist to listen into these conversations and capture the themes, producing a record of the exercise over the course of a day (see Figure 4).

Although we didn’t perform any standardised feedback exercise, our anecdotal impression was that many participants enjoyed this exercise. As one remarked, “it’s been great to talk to people that usually just pass by”. Following this success we began to develop other approaches that didn’t demand as much investment of time on the part of museum staff.

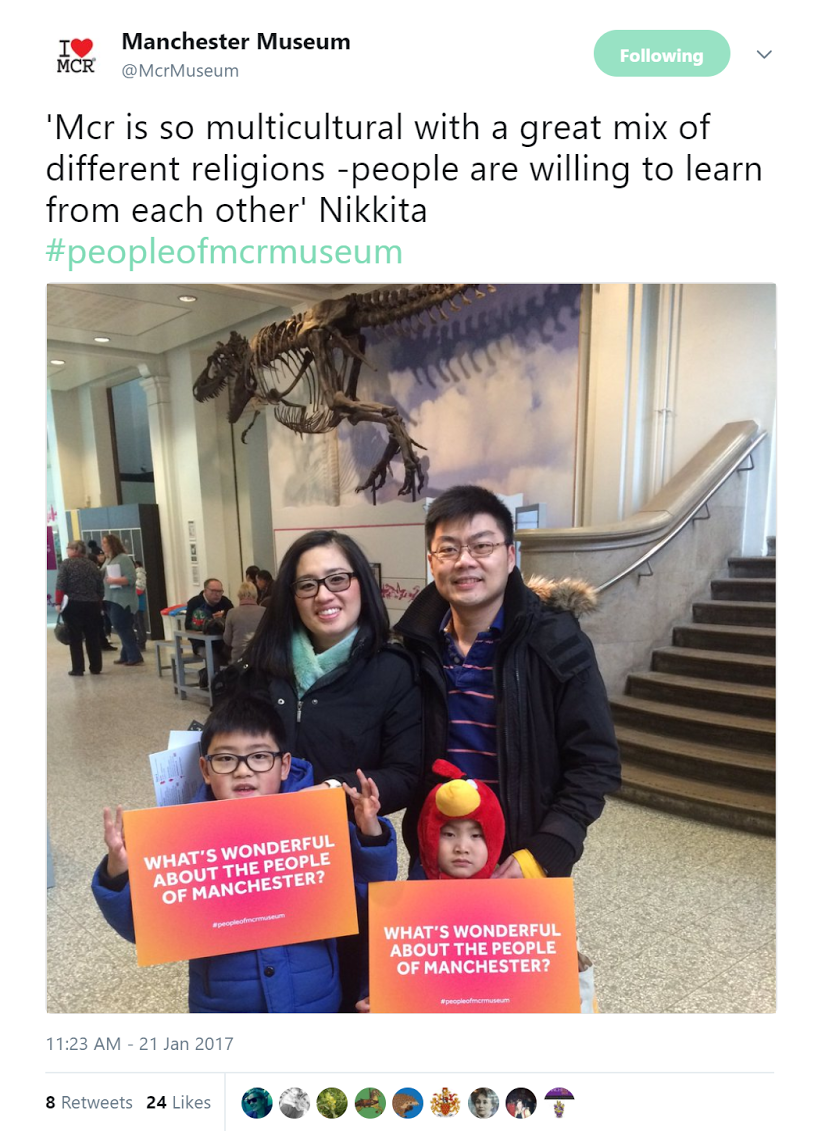

We took the exercise online, asking museum visitors to reflect on what they loved about their fellow citizens and Tweeting these reflections alongside a photograph (see Figure 5).

Implicit approaches

Work of the kind outlined in the previous two subsections led museum staff to reflect more deeply on the values that were implicit in a typical visitor’s experience of their time in the museum. It was recognised that some museum communications conveyed the implicit expectation that visitors held extrinsic values to be important while others overlooked opportunities to convey an implicit expectation that most visitors would (as we knew from our survey data) prioritise intrinsic values. This is important because as argued above, (Section 4.3) communications that convey implicit assumptions about what an audience values are likely to contribute to our collective understanding of our fellow citizens’ values.

The tendency to believe that our fellow citizens place greater importance on extrinsic values than is actually the case may become self-perpetuating if this leads to communications which seek to motivate responses through appeal to extrinsic values. Any communication which makes the tacit assumption that the intended audience is likely to be motivated predominantly by appeals to image, financial success, or self-interest may have this effect.

One very prominent communication in the museum was the invitation to donate. A donation box was situated prominently in the atrium to the museum, and another in the centre of the most visited gallery space. At the time we started working with the museum, this invitation to donate was relatively values-neutral (although note that drawing attention, even subtly, to money per se has been found to leave participants in studies less inclined to help strangers). We saw in this communication an opportunity to convey the understanding that most visitors to the museum would be motivated to donate as an expression of their intrinsic values, and we redesigned the donation boxes to reflect this. (See Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Before and after images, showing the donation box as it first appeared, and in redesigned form. Although not the primary purpose of this exercise, donations were found to increase significantly as a result of these changes.

Scaling up

The approaches that we trialled at Manchester Museum point towards a diversity of ways in which any organisation can begin to engage its stakeholders to convey the simple insight that most people prioritise intrinsic values. Of course, a visit to a museum is a small component of a person’s lived experience as a citizen of a city region. The effects of changes such as those we trialled are likely to be “washed out” by a person’s experience in other contexts – for example, in a shopping centre, when encountering pervasive outdoor advertising, or when reading or viewing local media. Experience in these contexts seems likely to contribute to an exaggerated understanding of the importance that most people place on extrinsic values.

If the values perception gap is to be closed, then this will be because it becomes part of a typical citizen’s day-to-day experience to encounter multiple reminders of the importance that his or her fellow citizens place on intrinsic values. Indeed, I would argue that to communicate in this way must be seen as key for any organisation that is taking its social and environmental responsibility seriously.

At the time of writing, and as a result of our work at Manchester Museum, we are now collaborating with a cohort of fourteen arts and cultural organisations across the Greater Manchester city region to help support these to develop more values-aware ways of engaging their audiences. But this way of working must extend beyond the arts and cultural sector to include organisations with large audience reach in many other sectors, including business, the media, sport, national and local government, and education.

Grounds for hope

This paper has explored the importance of people’s values and their perceptions of others’ values in determining a range of social outcomes, including prejudice toward outgroups. It has built the case that our social institutions exert important influence on both our own values and our perceptions of others’ values. Finally, it has reported on a pilot project with a museum where approaches were developed to reflect the values that most stakeholders prioritised, and to convey a more accurate understanding of their fellow citizens’ values.

The success of consumer capitalist economies is predicated on maintaining the fiction that most people are primarily self-interested – that they prioritise extrinsic values such as financial success and social status.23 Recent research shows that this fiction exacerbates division and prejudice towards outgroups and undermines commitment to take meaningful action on social and environmental challenges.

Consumer capitalism is built on an unspoken social contract. Your government will guarantee you certain liberties: to accumulate unbelievable wealth, to own property, to pass your wealth on to your heirs, to extract profit from public goods, to consume voraciously without concern for the social and environmental impacts of this consumption. But you must pay a price. You must accept that you will be conditioned into believing that you, and if not you then at least your fellow citizens, value these liberties more than anything else – more than your community, more than your love of nature, more than your compassion for people who are less fortunate, more than your concern for non-human beings.

It is difficult to develop this perspective without considering the role of the sociopolitical environment in changing citizens – that is, in exerting some form of “social engineering”. Yet, until the manipulative dimension inherent to consumer capitalism is widely recognised, its opponents find themselves in a bind. Only they face the charge of “social engineering”, because only they present any apparent threat to individual liberty as construed in these terms. We have been conditioned to turn a blind eye to social engineering when it operates to deepen our self-congratulatory but naive conviction that we are free and impervious to social engineering. This is consumer capitalism’s great jiu-jitsu move.

Margaret Thatcher, buoyed by her first election win and riding the wave of neoliberalism in the early 1980s, laid this contract bare with breath-taking confidence: her aim, she brazenly told her electorate, was to change their souls. Proponents of the neoliberal project rarely achieve such candour.

If division is to be healed – and if, for that matter, we are to achieve the depth and persistence of public demand necessary for proportionate action on inequality, structural racism or climate change – then it will be because we begin to see how the neoliberal project engineers a society in which care for others, community cohesion, and wellbeing are all suppressed.

This may seem daunting, but there are huge grounds for hope. Our values are on our side. We need simply to assert what is most important to us and to recognise these same priorities in our fellow human beings.

References

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-Perception Theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 6 (pp. 1–62). New York: Academic Press.

Bouman, Thijs, Linda Steg, and Stephanie Johnson Zawadzki. "The value of what others value: When perceived biospheric group values influence individuals’ pro-environmental engagement." Journal of Environmental Psychology 71 (2020): 101470.

Brunk, G. G. (1980). The Impact of Rational Participation Models on Voting Attitudes. Public Choice, 35, 549-564

Brunk, Gregory G. "The impact of rational participation models on voting attitudes." Public Choice 35, no. 5 (1980): 549-564.

Common Cause Foundation. "Perceptions matter: The common cause UK values survey." (2016).

Crompton, Tom, and Tim Kasser. Meeting environmental challenges: The role of human identity. Godalming, UK: WWF-UK, 2009.

Ferraro, Fabrizio, Jeffrey Pfeffer, and Robert I. Sutton. "Economics language and assumptions: How theories can become self-fulfilling." Academy of Management review 30, no. 1 (2005): 8-24.

Frank, R. H., Gilovich, T., & Regan, D. T. (1993). Does studying economics inhibit cooperation? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 159-171.

Frank, Robert H., Thomas Gilovich, and Dennis T. Regan. "Does studying economics inhibit cooperation?." Journal of economic perspectives 7, no. 2 (1993): 159-171.

Grouzet, Frederick ME, Tim Kasser, Aaron Ahuvia, José Miguel Fernández Dols, Youngmee Kim, Sing Lau, Richard M. Ryan, Shaun Saunders, Peter Schmuck, and Kennon M. Sheldon. "The structure of goal contents across 15 cultures." Journal of personality and social psychology 89, no. 5 (2005): 800.

Hanel, Paul HP, Gregory R. Maio, and Antony SR Manstead. "A new way to look at the data: Similarities between groups of people are large and important." Journal of personality and social psychology 116, no. 4 (2019): 541.

Hirschman, Albert O. The Passions and the Interests. Princeton University Press, 2013.

Kasser, Tim, and Susan Linn. "Growing up under corporate capitalism: the problem of marketing to children, with suggestions for policy solutions." Social Issues and Policy Review 10, no. 1 (2016): 122-150.

Marwell, G., & Ames, R. E. (1981). Economists free ride, does anyone else?: Experiments on the provision of public goods, IV. Journal of Public Economics, 15(3), 295-310.

Miller, D. T. (1999). The norm of self-interest. American Psychologist, 54, 1053–1060.

Schwartz, Shalom H. "Basic human values: An overview." (2006): 207-8.

Schwartz, S.H. (2007). Cultural and individual value correlates of capitalism: A comparative analysis. Psychological Inquiry, 18(1), 52-57.

Sheldon, K. M., & Krieger, L. S. (2004). Does legal education have undermining effects on law students? Evaluating changes in motivation, values, and well-being. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(2), 261-286.

Wallace, David Foster. This is water: Some thoughts, delivered on a significant occasion, about living a compassionate life. Hachette UK, 2009.

Wolf, Lukas J., Paul HP Hanel, and Gregory R. Maio. "Measured and manipulated effects of value similarity on prejudice and well-being." European Review of Social Psychology (2020): 1-38.

Author bio:

Tom Crompton, Ph.D. has worked for nearly a decade with some of the UK’s best known charities – including NSPCC, Oxfam, Scope and WWF – on values and social change. He has advised the UK, Scottish and Welsh governments on issues related to cultural values, has collaborated in research with some of the world’s foremost academics working in this area, and has published numerous articles on cultural values in both academic and popular journals. He co-founded Common Cause Foundation, for which he now works.

Common Cause Foundation

tcrompton@commoncausefoundation.org

Artist bio:

Qeas Pirzad’s work takes a critical view of the creation of personalized realities.

A descendant of Afghan transplants to the Netherlands, Pirzad quickly mastered the ability to occupy the contrasting worlds of life both in and out of his home. Much of his work is a reflection of the artist’s revelation of defining his own reality. Pirzad reflects on realizing societal and ancestral influences on his existence. Following an epiphany of these influences’ impact on his existence, Pirzad used his art to analyze and deconstruct the results of his previously prescribed reality.

Pirzad studied at the Royal Academy of Art at the Hague before moving to Berlin to work as an artist. His bodies of work utilize multiple styles and disciplines to communicate his rich lessons learned from the various parts of the world and social strata he has occupied.

As a multidisciplinary artist, Pirzad expresses his reality through several mediums such as oil on canvas, digital collage, sculpture, poetry, and performance art. He imagines this reality as one in which he can occupy multiple realms of his life without abandoning one for another. This multiplicity is revisited throughout Pirzad’s bodies of work. The dream-like compositions of Pirzad’s projects invite audiences to a visual journey free from boundaries. He hopes that this journey catalyzes viewers’ own awakenings.

Website: www.qeaspirzad.com

Instagram: @qeaspirzad

YouTube: Qeas Pirzad

Artwork title:

Uncovering our belonging

Art description:

As descendants of immigrants to Europe, we spend most of our life’s journey in the middle space between the values that represent the two different realities that we end up having to merge together. And that is of the place we are born in to and the place we originate from. The artwork is a visual representation of that journey.

- 1 Wolf et al., 2020

- 2 These are not terms used by Shalom Schwartz. “Intrinsic values” as I will use the phrase correspond approximately to the higher-order group of values that Schwartz calls “self-transcendence”. “Extrinsic values” correspond to the higher-order group of values that Schwartz calls “self-enhancement”. The different nomenclature that I will use arises from an alignment of the academic literature on human values with the related literature on human goals (see, especially, Grouzet et al., 2006). Following this literature, I will include some values defined by Schwartz as self-direction values (e.g. “curiosity”, “creativity”, “choosing one’s own goals”) as intrinsic values. For further discussion on this point, see, for example, Crompton and Kasser (2009).

- 3 Almost everyone holds all these intrinsic values to be important at some level, though the relative importance they are accorded varies from person to person.

- 4 Foster-Wallace, 2009

- 5The Sunday Times, 3 May 1981

- 6 This tendency to prioritise intrinsic values does not, apparently, arise because of a self-reporting bias (something for which it is possible to control).

- 7 Common Cause Foundation, 2017

- 8 The values perception gap does not, apparently, arise because of self-reporting bias – we were able to control for the possibility that survey respondents may tend to exaggerate the importance that they personally place on intrinsic values. We controlled for self-reporting bias using the 16-item version of Paulhus’ Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (Bobbio & Manganelli, 2011). Bobbio, A., & Manganelli, A. M. (2011). Measuring social desirability responding. A short version of Paulhus’ BIDR 6. Testing, Psychometrics Methodology in Applied Psychology, 18(2), 117-135.

- 9 Hanel et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2020

- 10 See Wolf et al., 2020. Note that there are two factors in consideration here, both of which predict prejudice: a participant’s own values and a participant’s perceptions of a Muslim’s or economic immigrant’s values. Prejudice is lower among participants who attach greater importance to intrinsic values, regardless of their perceptions of the values of Muslims or economic migrants; it is lower among participants who believe that Muslim’s or economic immigrants attach greater importance to intrinsic values, regardless of the importance that a participant places on these values himself or herself. It is lowest among participants who both attach importance to these values themselves and believe that Muslims or economic migrants also attach importance to these values. Note that the values perception gap explored here is between a participant’s values and the values that they ascribe to either a Muslim or an economic migrant, rather than the values that they ascribe to an imagined “typical citizen” as in Common Cause Foundation’s research.

- 11 Bouman et al., 2020

- 12 Bem, 1972.

- 13 Miller, 1999.

- 14 See Frank et al.,1993; Brunk, 1980; Marwell & Ames, 1981.

- 15 Sheldon & Krieger, 2004.

- 16 Kasser & Linn, 2016; Schwartz, 2007.

- 17 Frank et al., 1993; Brunk, 1980.

- 18 Ferraro et al., 2005.

- 19 Miller, 1999.

- 20 Ibid, p. 1053.

- 21 At the time of the project, Manchester Museum attracted some 450,000 visitors a year. With support from Minor Fund for Major Challenges, we employed a learning and engagement officer for a twelve month period, 2016-2017, who worked with museum staff to prototype and test approaches to closing the perception gap.

- 22 Hanel et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2020.

- 23 Hirschman, 1977.