“The poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he,” said Rainsborough, “and therefore truly, Sir, I think it’s clear that every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice to put himself under.”

So spoke Colonel Thomas Rainsborough of the New Model Army, rising to his feet during the Putney Debates of 1647. The context was a half-won civil war: with Charles I under house arrest at Hampton Court Palace, the soldiers of the New Model Army had come together at St Mary’s Church in Putney, south west London, to debate how to run a kingdom without a king. Rainsborough’s call articulated for the first time in England the principle of universal suffrage (or at least universal male suffrage), positioning it as a fundamental precondition of legitimate government.

In the terms offered by john a powell and the Othering and Belonging Institute, Rainsborough was also offering a design principle by which government might be reoriented towards belonging. At that time, power in England was wealth - the more you had of the latter, the more of the former - and, more importantly, that was the way it should be. The wealthy and noble-born were the God-given. They knew best, so they should be in charge; in powell’s terms, only they “belonged”, since only they had the right to participate in the making and shaping of society. The rest were marginalised, “othered”. In its context, Rainsborough’s argument - that the power and voice offered by the right to vote must be disconnected from wealth - was radical in the best and deepest sense of the word.

In April 2014, my business partner Irenie Ekkeshis and I chose St Mary’s Church as the venue to launch the New Citizenship Project (NCP). The event was called “People Power in the 21st Century: The New Putney Debates”, in honour of what had taken place on the same site nearly four centuries before. Irenie and I started NCP as a consultancy business in terms of its revenue model, but more importantly as an inquiry into an analogous, expanded shift in power and belonging. As the team has grown, NCP’s work has remained rooted in the belief that by nature, human beings - regardless not just of wealth, but of race, gender, creed or anything else - are collaborative, caring, creative creatures who want and indeed need to shape the communities and societies we are part of. To belong. In the 21st century (as opposed to the 17th), that shaping can and must extend beyond the occasional vote to appoint a government – to the opportunity to contribute ideas, energy, and voice to every aspect of the work of doing life together.

In this essay, I first set out NCP’s underlying conceptual framework of the Citizen Shift, then offer some reflections on this work in the light of the approach of the Othering and Belonging Institute. I then offer the three design principles NCP works with as a starting point for supporting organisations and institutions of all shapes and sizes - large, small, government, business, charity, or anywhere in between - to cultivate participation and belonging. I close by offering an updated version of Rainsborough’s intervention, and a diagnosis of the moment in time I believe we in Britain are now living in.

The Citizen Shift

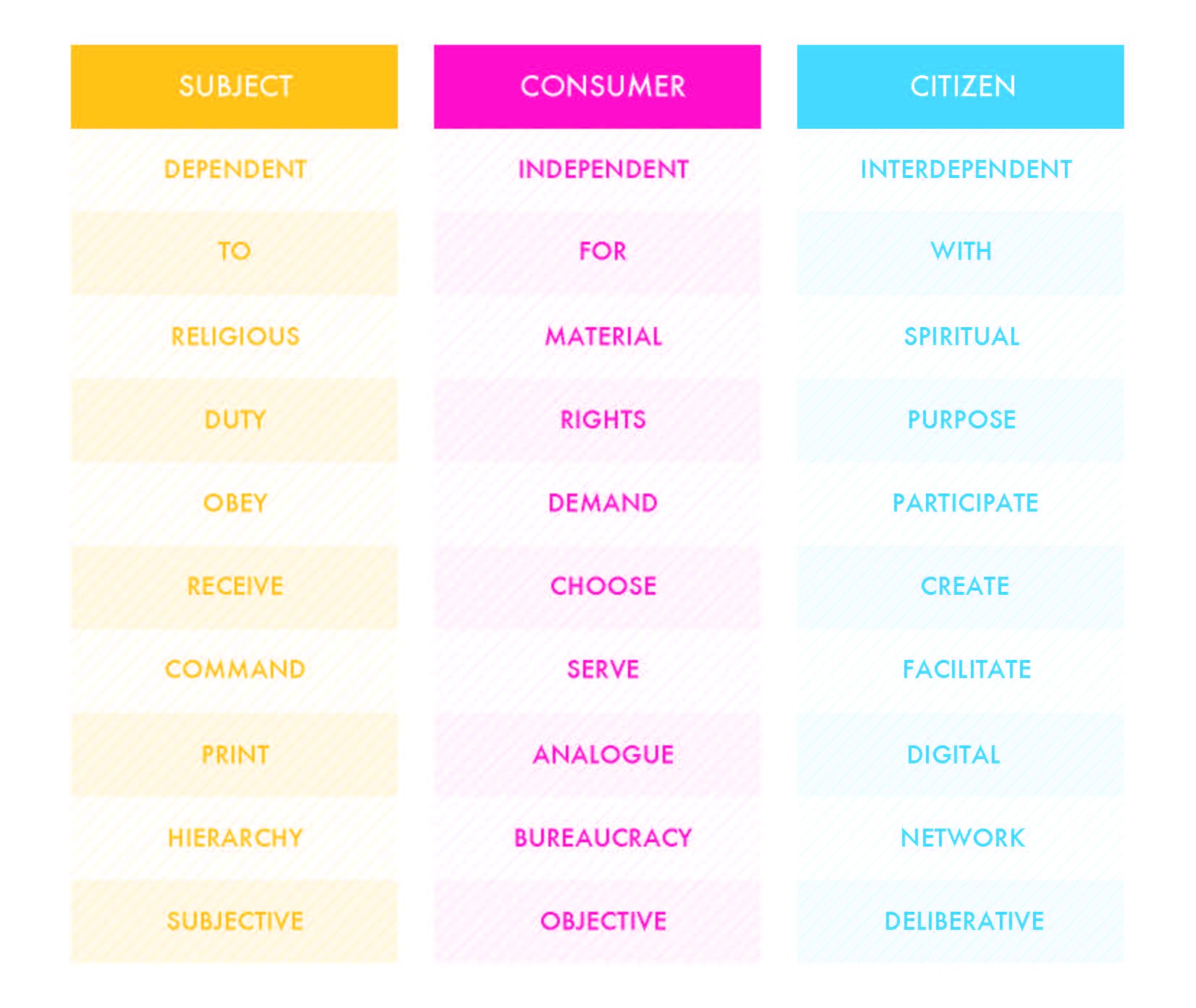

NCP’s work is rooted in the insight that there is such a thing as a dominant story of the role of the individual in society, and that this story can change, and is changing. This is a fundamental shift, one that shapes how each of us understands ourselves, our interactions with one another, and what we can and should do in every aspect of our lives. It is the second shift at this level that has taken place in the last century: in the 20th century, the dominant story shifted from Subject to Consumer; now it is shifting from Consumer to Citizen.1

The shift from Subject to Consumer emerged over the course of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, culminating in the two world wars. In the Subject Story, and in particular in its manifestation in the British Empire under Queen Victoria, the right thing to do was know your place, keep your head down, do what you were told, get what you were given. Since the few with God-given power knew best, this was the path to the best outcome for society as a whole. The Subject Story existed in the age of empire, aristocracy, duty, and conformity. But it began to creak under its own logic as the middle classes grew, as women found voice, as the colonised began to reject; and then collapsed in the trenches and on the battlefields, as classes previously kept apart were viscerally confronted with their basic shared humanity.

The Consumer Story that emerged from the wreckage represented a hugely liberating shift, one that finally delivered (or so it seemed) on what Rainsborough had first articulated three centuries before. Now we deserved better - and if we sought better, the best society would result that way. We gained the power of choice. In the era shaped by Milton Friedman, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, the golden promise was that self interest would add up to collective interest. The right thing to do for individuals was to look out for yourself, to choose the best option for you from those that were offered, and for organisations and institutions, to produce whatever people would consume.

As the 21st century dawned, though, the limits of the Consumer Story were becoming clear. More people had more power than under the Subject Story, but too many still had far too little. The Consumer Story had promised to break the link between wealth and power, giving everyone a voice, but in truth it did not, since the scale and range of the choices available to you remained dependent on the money you had to access them.

The seed of crisis, though, lies in the fact that in a world of challenges that demand collective action, the power of individual choice and the logic of self interest are increasingly obviously insufficient. As a result, indeed, as climate change has become a climate emergency, and as local and global inequality has veered into obscenity, the Consumer Story is beginning to fall apart, just as the Subject Story before it. We are stuck in a cycle of attempting to solve our problems by working from the same logic that created them in the first place. To find the solutions we need, we must first see ourselves differently.

Hope lies in the fact that a shift at this deep and foundational level of story is under way. When the Subject Story was creaking, the Consumer Story was emerging; in the same way, I contend in this essay, as the Consumer Story has begun to creak, the Citizen Story is emerging and taking ever fuller form. If as Subjects we did as we were told and disappeared into the mass, and as Consumers we atomised and looked out for ourselves, as Citizens we can get involved, contributing our unique view to the greater whole. As Subjects we had no meaningful power; as Consumers we gained the power to choose between the options; as Citizens we are discovering the power to shape what the options are.

On Citizenship and Belonging

It is important to acknowledge before going any further that “citizen” can be a charged and troublesome word, wielded heavily in the nationalism, protectionism, and racism surging across the world. Access to work and healthcare, freedom of movement, the opportunity to vote, and protection from deportation count among the benefits an official “citizen” has, and a “non-citizen” does not. Policies, law and culture around migration, immigration, and naturalisation determine who gets these and who does not.

This usage of the word “citizen” as a tool to demarcate social lines and to allocate resources represents the co-option and perversion of what is a crucial concept. It represents an abuse that must be contested and fought; there is simply no other term that can replace citizen, and carry the same implicit combination of freedom, interdependence, and individual agency that is so essential to the creation of any positive future. In developing this understanding, the work of john a powell and the Othering and Belonging Institute has been a vital source of inspiration. Indeed, in getting to grips with belonging, I have come to believe citizenship is not just a related concept, but the same by a different name: to be a citizen is, in the way I use the term, to belong.

Ideas of membership and power lie at the heart of citizenship-as-belonging. This is most clearly stated when powell and others explain the contrast between the concepts of belonging as opposed to diversity (a fact about the ratio of represented groups in a space or institution), inclusion (an act of allowing entry into a space or institution), and equity (an act of addressing existing resource disparities within a space or institution). Belonging goes beyond all these, insisting not just on fair access to resources, but to the power to shape the terms on which the space or institution operates. As powell and Menendian write, “the most important good we distribute to each other in society is membership. The right to belong is prior to all other distributive decisions since it is members who make those decisions.”2 Belonging, they write elsewhere, is “the agency to contribute to the evolution or definition of that to which we belong or seek to belong.”3

The overlap between this and the Citizen Story I have been working with is complete. I see citizenship as the holding of agency in community: citizens can and do shape the organisations, communities, and societies of which they are part, and are defined by the fact that they do so. Citizens are members of society. Citizen is the noun, belong the verb. Such an understanding of citizenship is in fact both deeply rooted in the etymology of the word, and gaining in momentum in popular parlance. “Citizen” literally translates from its latin roots as “together-person”: one who is definitionally interdependent, who can only be understood in relation to the collectives of which they are part. Today this understanding is perhaps best expressed by Baratunde Thurston, who goes one step further than me and argues that “citizen” might itself be best understood as a verb rather than a noun. Opening his podcast How To Citizen With Baratunde, Thurston identifies four parts to what he calls “the practice of citizenship”:

“First, to citizen is to participate. It's a verb, not a noun, not an adjective, it's to show up. All right? Number two, to citizen is to value the collective, and to work towards outcomes that benefit the many. And not just the few. Number three to citizen is to understand power, and the various ways we have at our disposal to use it. And number four, to citizen is to invest in relationships with others, and recognize our interconnectedness.”4

The second crucial aspect of the Institute’s concept of belonging is its fundamental opposition to and contrast with othering, defined by Menendian and powell as “a set of dynamics, processes, and structures that engender marginality and persistent inequality across any of the full range of human differences based on group identities.”5 Cultivating belonging, by contrast, is a process of growing “the circle of human concern,”6 drawing the marginalised in. This understanding of the relationship between othering and belonging resonates strongly with the dynamics of the stories of Subject, Consumer and Citizen. The Subject and Consumer stories are both inherently and inevitably stories of othering.

In the Subject Story, this is obvious: the structure of society is understood as a hierarchy, in which there are a few at the top who have great power and those further down who have progressively less and less, down to the levels of complete dehumanisation. This is how empires were sustained. The Consumer Story promised to change all that. Self-determination was the watchword; everyone would have the power of choice; those who had been in power would now be in service. Yet, when you start to look for them, othering dynamics become visible as equally inherent in the Consumer Story. When commentators talk about people as consumers, they project assumptions of narrow material self interest as the driving human motivation, and of the atomised individual as the unit of human action that are both deeply othering. What is worse, in doing so they validate and reinforce these assumptions in wider society, increasing their influence on individual behaviour. There is experimental evidence for this: in a series of studies published under the title Cuing Consumerism, a team of social psychologists at Northwestern University found that prompts as light as the introduction of the single word “consumer” into the framing of a questionnaire or scenario made respondents less motivated by social or environmental concerns, less willing to trust or compromise - and even made them less happy.7 It is interesting to note that whenever the language of “consumers” is used, the pronoun becomes “they” rather than “we” - those making this reference never seem to consider themselves part of the mass.

By contrast, the work of creating and cultivating the Citizen Story is not only about opening up power, it is also a process of decreasing marginalisation. Citizens are not “they”, but “we”: the underlying assumption being that all of us are smarter than any of us. Involving more people in both quantity and crucially in diversity - and doing the work to structure processes so that all those people are able to contribute at their best - becomes the default strategy.

The third and final aspect of the concept of belonging I want to reflect on in this essay is the language itself, and its potential for co-option. Both "citizenship" and "belonging" are contested and contest-able concepts, and indeed contested and contest-able words.

In my work on citizenship, I have started drawing a distinction between Citizenship-as-Status and Citizenship-as-Practice (following Baratunde Thurston). Citizenship-as-Status, indeed, represents the Consumer-isation of citizenship: its reduction to a possession. This is in large part because of the way the language of citizenship has started to be used in public discourse. For example, in October 2016, shortly after the vote that resulted in Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union, Theresa May used her first speech to the Conservative Party Conference as Prime Minister to argue for what she called “the spirit of citizenship”:

“That spirit that means you respect the bonds and obligations that make our society work. That means a commitment to the men and women who live around you, who work for you, who buy the goods and services you sell. That spirit that means recognising the social contract that says you train up local young people before you take on cheap labour from overseas. That spirit that means you do as others do, and pay your fair share of tax. But today, too many people in positions of power behave as though they have more in common with international elites than with the people down the road, the people they employ, the people they pass in the street. But if you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the very word ‘citizenship’ means.”

Three years on, with May now consigned to the back benches, a think tank led by her former chief adviser published a report called The Politics Of Belonging8 , arguing that the moment in time we are living in is one in which the pursuit of increasing social and economic freedom has come to an end, and that the deep need now is for three kinds of security:

- Economic security: higher skilled and higher paid jobs, a focus on homeownership, a more contributory welfare system, and better technical education.

- Cultural security: prioritising citizenship, community integration, immigration control, and a revival of neighbourhoods and civic life.

- National security: investing in defence, tougher and more visible policing, and a more robust regime to punish and rehabilitate offenders.

These ideas are indicative of and influential in the direction of the current British government, which uses much of the same language. Yet there is something deeply worrying here, which feels more like a co-option than a channelling of the democratising power of the ideals of citizenship and belonging. This risk of co-option focuses our attention on the need to be clear and precise in what we mean by these concepts, so as to be equipped to call out (or perhaps call in9 ) those occasions in which they are misused.

The Three Principles of Participatory Organisations

If the task we face is to shift the story of society - or at least to support a shift that’s already emerging - the next question is: what do we actually need to do? There is no utopian switch we can flip to shift the story overnight. The pioneer of systems thinking, Donella Meadows, uses the language of “paradigm” to refer to what I call “story”; she offers this definition of the work in her essay Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System:

So how do you change paradigms? In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you keep coming yourself, loudly and with assurance from the new one, and you insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power. You don’t waste time with reactionaries; rather you work with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded.10

As the Consumer Story collapses, we need to make sure as many people as possible can see that it is the story that is collapsing. We must neither accept what we are given as the only possibility, as Subjects do; nor throw our toys from the pram when we do not like what is on offer, as Consumers do. As Citizens, we must propose, not just reject. We must wake up to our agency in an interdependent world. We must start from where we are, accept responsibility, and create meaningful opportunities for each other to contribute as we do so. We must step up, and step in. As such, the work of Citizens is not so much about traditional activism, as it is about seeing ourselves and therefore our work with new eyes - wherever we stand. One of my mentors, the Israeli strategist and complexity theorist Dr Orit Gal, evocatively calls this kind of work “social acupuncture”: intervening at multiple points to release the energy for the new story to emerge and take hold. This way of thinking and working is so empowering precisely because the moment of collapse of the Consumer Story and emergence of the Citizen Story is recognisable across organisations and institutions of all shapes, sizes, and sectors. It is work that can be done from anywhere, and indeed, must be done from everywhere.

Over the seven year journey of the New Citizenship Project, the team has developed a model of three principles to help organisations and institutions recognise and undertake this work to support the development of the Citizen Story; each is best expressed in the form of a question.

Purpose: What is the organisation trying to do in the world that’s so big it needs to do it with people, not just for them?

Platform: What structures and processes does the organisation make available to make it joyful and worthwhile to contribute to that purpose?

Prototype: How can the organisation start to build momentum behind these ways of involving people, since it is impossible to flip a utopian switch and transform overnight?

As the team has worked with these ideas and questions, it has become increasingly clear that this is not a shift that must be created from scratch, but rather is work that is bubbling up everywhere - and that these principles can help both recognise and formalise, naming the work so that it becomes easier to do. Indeed, once you have this language, you start to be able to see how the Consumer Story shows up everywhere, but also how the ideas of the Citizen Story are emerging.

This is perhaps most clearly the case among major charities. Under the influence of the Consumer Story, the norm has been for these organisations to divide themselves, in effect, into two parts. One part faces funders and donors, competing for their "custom" and providing "benefits"; the second provides services for beneficiaries. Both sets of stakeholders are treated as Consumers, and in the process, the organisation all too often loses sight of the inequities of agency and power that represent the deeper challenge they exist to tackle.

Yet as charities start tentatively to step into the Citizen Story, we see these structures being disrupted. More and more such organisations are ensuring that "beneficiaries" are directly represented on their boards and in their workforce. Communications teams are increasingly conscious of the need to cultivate and celebrate agency in their campaigns, not just evoke pity. Participatory grant-making is changing the power dynamics of philanthropy of all kinds. All these are examples of a growing shift from Consumer to Citizen logic in the charity sector.

The same situation - Consumer Story dominance yet at the same time Citizen Story emergence - is also present in the public sector, the realm of government. I would go so far as to argue that we are experiencing the inevitable collapse of Consumer democracy - a democracy in which our agency is limited to choosing between options set for us once every few years, a choice which we are increasingly expected and conditioned to make on the basis of narrow self interest. Yet at the same time, a whole new paradigm of democracy is taking shape. It is emerging across the world - from Taiwan to Chile, Paris to Reykjavik - and taking many forms - from citizens’ assemblies to constitutional conventions to open policy-making to participatory budgeting. These places and processes hint at a richer, deeper future for democracy. They show that true democracy is about far more than elections, that citizens can and want to do far more than vote.

Finally, the shift is visible in the private sector too. Milton Friedman’s dictum that “the social responsibility of business is to maximise its profits” is as pure an expression as any of the logic of the Consumer Story, and its logic remains dominant; yet it is now increasingly coming under challenge by a growing chorus of ever more influential voices. Theoretical debate is starting to translate into practice. Investors and shareholders are demanding social purpose, and businesses are responding. As they do so, they stop acting as Consumer of society - maximising their self interest in the form of their direct profits, no matter what the cost - and instead start to act as Citizens in society. Such businesses understand and operate on the basis that business must support the societal structures on which they depend for a safe and stable operating environment.

Taking each of NCP’s three principles in turn, and drawing on case studies both from NCP’s work and beyond, we can see these headline shifts in action in more detail, and understand how we might make them happen more consciously, effectively, and quickly.

Purpose

If an organisation is to involve people in its work in the world, the first task is to understand and articulate what that work is; not what the products and services are, but what the higher task is that’s so big it must be shared. Too often, even the most apparently purposeful organisations of all sorts lose sight of this higher purpose as they develop and then manage transactional delivery mechanisms.

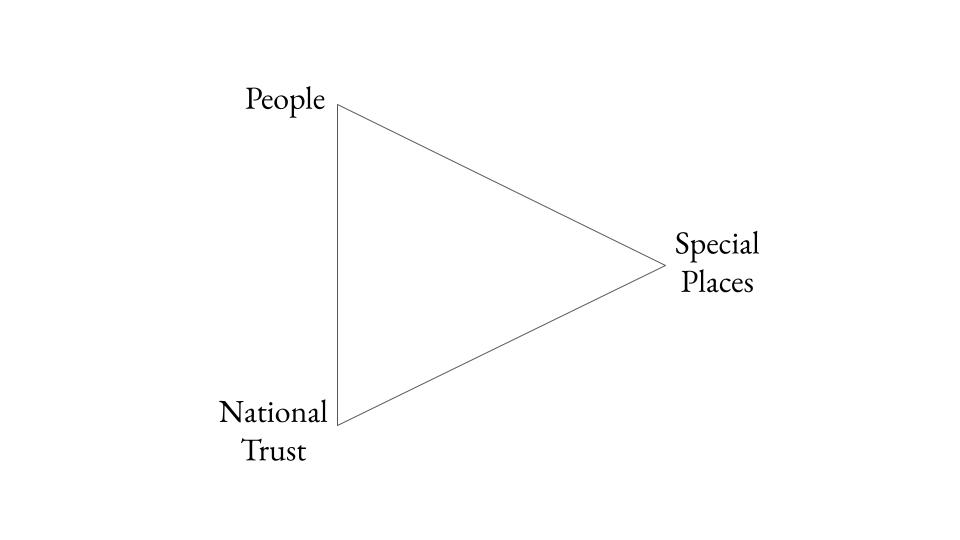

My favourite case study in this space remains work I was involved in, starting just before co-founding NCP, at the National Trust. The starting point was an organisation that had become deeply divided, a division that was represented in the form of a triangle:

The Trust had become two separate organisations. One part worked on the axis between the National Trust and the “special places” it owned; conservation and curatorial teams working to understand and protect castles, houses, and gardens - implicitly at least, from people. The second worked on the axis between the Trust and people, as a “day out” attraction business selling tickets to visitors-as-consumers. In a highly linear process, marketing would sell visits to glossy, glamorous properties; properties would convert visitors to annual membership on the basis of the consumer logic of it being cheaper to join than to pay for four separate visits; and members would then and only then be asked to donate to conservation projects.

What had become lost was the relationship that really mattered: the relationship between people and place. Served up their perfectly confected days out, people were given little opportunity to connect with the work that went into sustaining and understanding these places, and almost no opportunity to be part of exploring and uncovering their lessons for the present.

The critical conceptual step was to articulate a purpose that sat firmly on this undervalued axis. The Trust existed to “grow the nation’s love of special places” - to give everyone the chance to connect with, explore, and understand nature and history through the medium of place, fulfilling a fundamental human need for such connection. This purpose quickly manifested in multiple changes. One such change was to rebrand lowly Wardens, odd job men (and they were almost all men) in camouflage uniforms whose job description was essentially to protect nature from children, as vital Rangers, made visible in striking red fleeces and out actively celebrating and sharing opportunities to connect and contribute. Marketing campaigns like 50 Things To Do Before You’re 11¾ became less about selling tickets than building connection, and crowdsourcing ideas for the list in the process (and selling more tickets as a result); membership became a cause to join, not just a product to buy.

The end result of all this, in purely commercial terms, was that the Trust achieved its 2020 target of five million members in 2017. Far more importantly, the leadership has embraced the logic of giving everyone the chance to connect. This has made an organisation that had arguably provided weekend playgrounds for the older white middle- and upper- class, into a pioneering force in exploring and understanding the history of these places, and the significance of slavery and the oppression of empire in many of their stories. In doing so, it has opened them up to become places where far more and more diverse people feel they belong. In doing so, the National Trust has itself become an organisation in which many people feel a deep sense of pride, attachment, and belonging - and which they are prepared to defend when they sense it coming under attack.

The triangle above is one tool, the National Trust one organisation; there are many others. The question is the most important thing. If any organisation in any sector is seeking to identify its role in the Citizen Story, the starting point is the question: What is the organisation trying to do in the world that’s so big it needs to do it with people, not just for them?

Platform

The reframed role of the Rangers and the framing of marketing campaigns as opportunities for connection at the National Trust hint at the second principle. Once purpose is identified and understood, the next challenge is to open up involvement in that purpose - and indeed to understand and celebrate the opportunities that already exist.

The public sector is perhaps the most exciting space for this work, both because the idea that government might be a space for joyful, worthwhile interaction and contribution is so obviously not the case at present, and because that is exactly what should be the case. What should democratic government be if not a space where everyone belongs, to which everyone has the opportunity to contribute? Yet in the Consumer Story our “involvement” is limited to choosing between representatives once every few years, often with a justified sense that the vote I cast makes little meaningful difference.

My favourite example of this kind of truly participatory rather than just narrowly “representative” democracy - and one I claim no credit for - is the work that led to the legalisation of access to abortion up to 12 weeks in Ireland. In May 2018, a little under two years after the Brexit referendum, over 66% of the Irish electorate voted in favour of this change. This was a seismic shift in women’s rights in a traditionally Catholic nation, where the issue had been stuck in the political quagmire for decades. It happened despite a referendum campaign that was subject to all the same tricks and manipulation that we now know to have influenced almost every election or referendum in the world over the last five years, quite possibly the last decade.

The campaign was “immune” to this manipulation (in the words of columnist Fintan O’Toole11 ) because of the process by which the legislative recommendation was produced: a Citizens’ Assembly, bringing together a randomly selected, representative sample of Irish citizens for five weekends over five months to learn from expert witnesses (including those with lived experience), deliberate with one another, and come to a recommendation. The recommendation they came to was a more liberal proposal than any Irish politicians had ever considered possible.

When this very specific proposal went to referendum, the Irish population were not just informed in their own considerations by distant “experts”, but by people like them - including many who had changed their minds through the deliberative process. It proved a powerful antidote to lies and misinformation, creating a much more positive environment for debate and, after the vote, healing of the divides.

It’s important to emphasise how different this kind of process is, in particular the Citizens’ Assembly element - which is itself one form of what is known as “deliberative democracy”. In the standard “democratic” process of the day, consultation after the formulation of a policy framework is the beginning and end of the opportunity for citizen involvement. These processes are often bordering on the impenetrable, largely because so much work will already have been done; the result is that they are often tokenistic, designed consciously or otherwise to minimise rather than maximise participation. They then attract only the most impassioned, with the result that the majority of the citizenry are pushed yet further away from true involvement in government.

Deliberative democracy is again just one tool that can help structure participation in the work of an organisation or institution. Such tools make it manageable to involve people, at the same time as making it worthwhile, meaningful and (hopefully!) fun to be involved. That’s when organisations become platforms and in doing so create belonging - not by abrogating the responsibility for decision-making or direction-setting, but by holding those responsibilities openly, allowing and encouraging people to help, learn, inform and contribute to them. If government can do it...

Prototype

The final principle is really about the work of getting started. This is in some ways the hardest part, since once it starts to flow, the natural human energy for participation and involvement takes some stopping. This work is often more about understanding, spotlighting and celebrating the parts of organisations where Purpose and Platform are already present, than it is about creating something from scratch. It is as much about creating critical connections, where people across an organisation see and sense what one another are up to, as creating critical mass.

One organisation where I’ve seen this principle apply powerfully has been the Co-op, with which NCP has now worked for almost four years, gradually supporting the emergence (arguably, the reclamation) of a more participatory approach as the organisation has regained its confidence in its model and approach following a hugely difficult period in the early 2010s.

This began with the involvement of two different teams from within the Co-op in two different NCP projects, inquiries into the role of participation in the future of the food system, and into the future of membership organisations, respectively. The food policy team desperately wanted to involve people in their policy development process instead of just selling them food; the member “voice” team were desperate to get beyond research on people and into co-creation with people. With a little encouragement and support from NCP, these teams started working together much more. Now the energy they have started to build between them has attracted more teams across the organisation to experiment with different ways of working: perhaps the most profound example being the funeral care team, who responded to the tragic consequences of the pandemic by supporting grieving individuals, families, and communities to connect and self-organise online, leading conversations and holding reflective spaces for one another in a network of support that spread across the country at the moment of greatest need.

At its founding moment in 1848, a small group of traders got themselves organised, pooled their capital, and invited their customers to do the same, in order to provide affordable access to decent quality goods. As they grew and spread, they dispersed power throughout the network, with local Co-ops becoming places of agency, belonging, and community support across the country. That heritage got lost as the Co-op arguably became just one among many outlets for ethical consumption, but is now being reclaimed. NCP has done little apart from offer the occasional prod, but when that human inclination to involve and be involved is unlocked, that’s all that is required.

Conclusion

Every human in Britain has a contribution to make. As such, every one of us has a right to belong - to participate in shaping the institutions of government that in turn shape and structure our society - and should be considered a citizen by default. Any government which does not open these opportunities, to all, should not be considered legitimate.

The above is a thought experiment: my attempt to translate Colonel Thomas Rainsborough’s famous intervention into its present day equivalent in the light of these reflections on the theory and practice of cultivating belonging in Brexit-era Britain. It is a radical statement, one that if adopted, would offer a dramatic challenge to British society. But that is perhaps the point. Rainsborough was drawing attention to a fundamental flaw in the structure of society, arguing that until such time as it was fixed, society would deservedly be in danger of collapse; this statement does the same.

While the work to cultivate the Citizen Story can be done from anywhere, and must be done from everywhere, the resonance of Rainsborough’s statement reminds us that it is government that most has a duty to step into it. We live in a moment in time when it is fundamentally possible to involve far more people - and far more diverse people - in the processes and decisions that provide the structure and parameters for our daily lives. Techniques like Citizens’ Assemblies, open policy-making, participatory budgeting, and so on are now tried and tested, proven not just to increase the legitimacy of government but to improve societal outcomes. There is data, too, to suggest that the desire for participation, belonging, and citizenship is there, and that it is growing. The polling company YouGov recently found that the popularity of a “Citizen approach” to government, involving “giving everyone the opportunity to have their voice heard”, would far exceed that of other alternatives.12 More In Common recently found that at a local level at least, the pandemic is increasing the sense of belonging significantly, at least at a local level: the proportion of us who feel we can make things better in our local communities has risen from 47% before the first UK lockdown to 68% a year later.13

Yet meaningful opportunities to participate in shaping British society are few and far between, for any of us, let alone the most marginalised. The UK Climate Assembly is just the latest and most significant example of a process that could easily have invested genuine power in a representative and therefore symbolically powerful sample of the population; yet, while it is widely recognised to have put forward a powerful and sensible agenda for the national response to the climate emergency, its recommendations have been entirely ignored by our government.

My overriding sense after seven years of working with these ideas, and particularly having enriched my understanding further by integrating them with those of the Othering and Belonging Institute, is an ever deeper conviction that the current state of play cannot hold for much longer. Britain will either step into the Citizen Story, embracing the truth that all of us are smarter than any of us and the tools that allow that truth to be turned into action, or - as happened after the hopeful, visionary moment of the Putney Debates - this country will return to a state of oppression, othering, and subjection.

I know which future I am working for.

Author bio:

Jon Alexander began his career in advertising, winning the prestigious Big Creative Idea of the Year before making a dramatic change. Driven by a deep need to understand the impact on society of 3,000 commercial messages a day, he gathered three Masters degrees, exploring consumerism and its alternatives from every angle. In 2014, he co-founded the New Citizenship Project to bring the resulting ideas into contact with reality. His book CITIZENS: Why the Key to Fixing Everything is All of Us, is published on 17th March 2022.

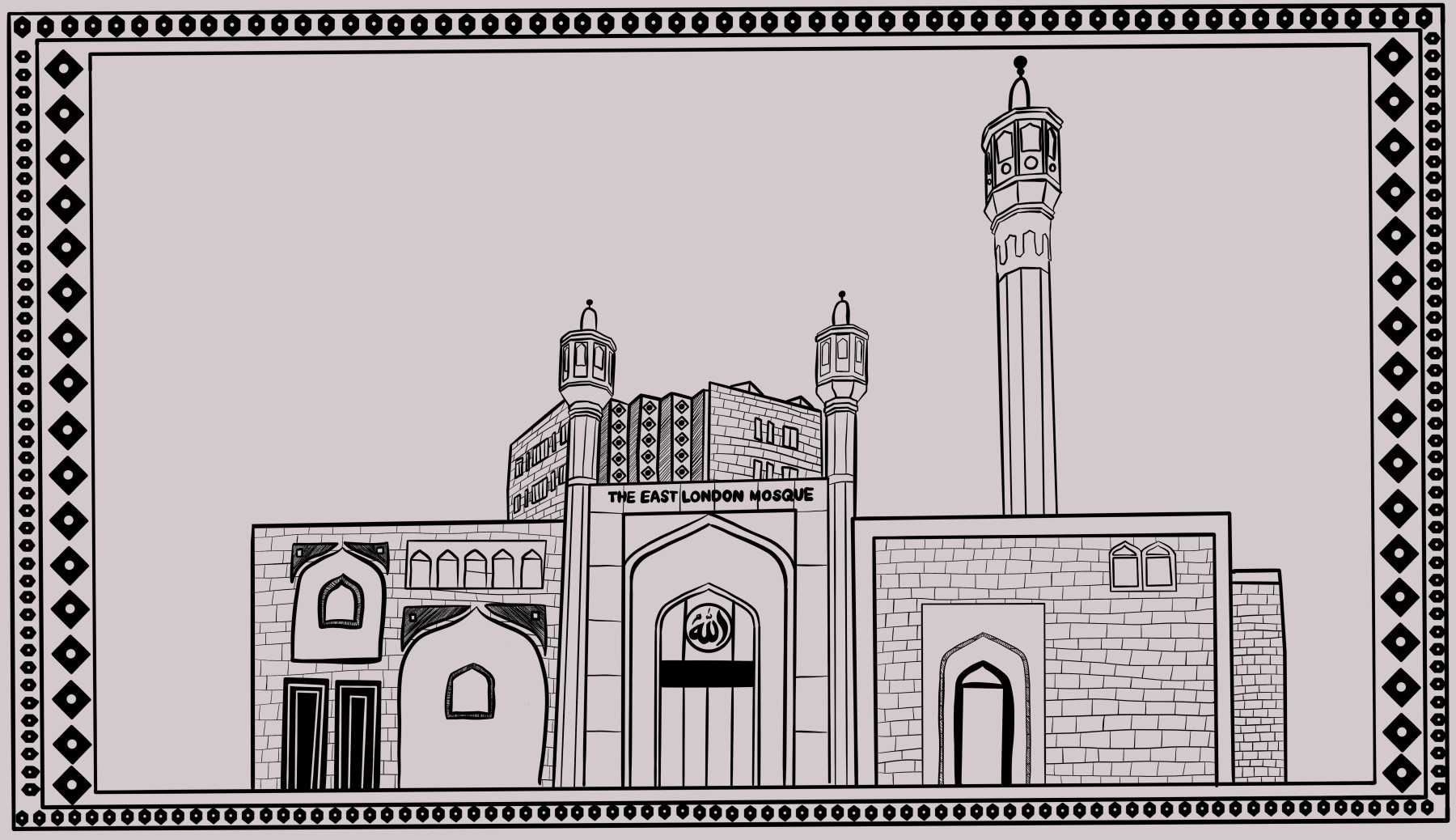

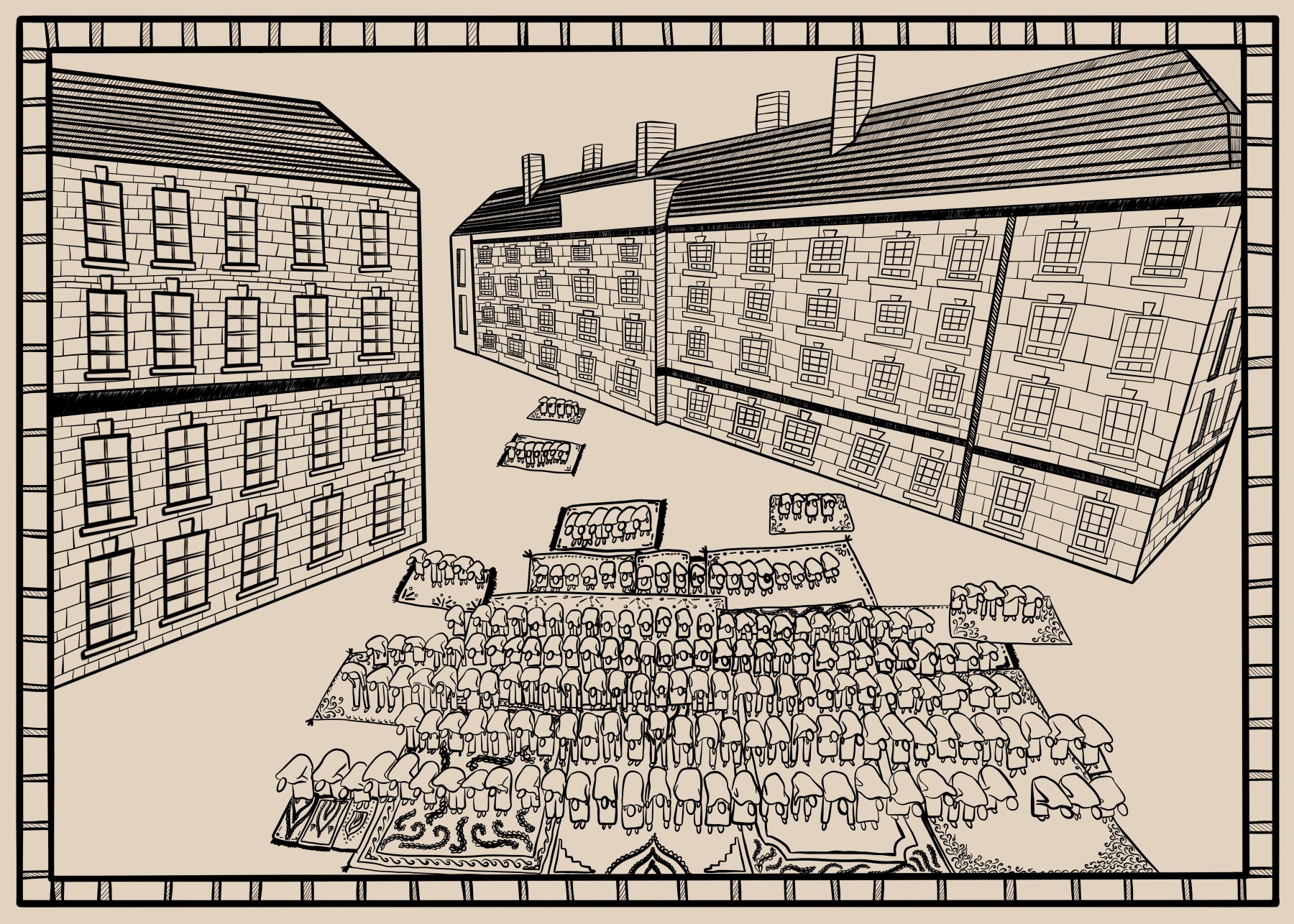

Artist bio:

Alaa Alsaraji is a visual artist, designer and creative facilitator. Through her creative practice she aims to explore themes such as belonging, reimagining space and community, predominantly using the medium of digital illustration. She also works as a facilitator, delivering creative workshops. Alaa is also the arts editor of Khidr Collective.

Art description:

With rising Islamophobia, fuelled by hateful media rhetoric, State surveillance and the criminalisation of Muslim communities, our families and communities often feel unwanted, targeted and both physically unsafe and socially isolated, cautious to fully be ourselves and embrace our heritage and faith within British society. Despite these external conflicts, which have expanded over generations, communities have established and maintained their own safe havens, often improvised and built out of necessity, these spaces create a sense of belonging and safety. ‘Mapping Sanctuaries’ is a digital illustration and audio series highlighting the spaces that British Muslims from different backgrounds have created or ‘carved out’ for themselves, enhancing a sense of belonging and ultimately creating a sanctuary from the realities of life as British Muslims.

- 1 New Citizenship Project, “This Is The #CitizenShift”, November 2015, https://www.citizenshift.info/

- 2 john a. powell & Stephen Menendian, “The Problem of Othering: Towards Inclusiveness and Belonging,” Othering & Belonging Issue 1 (2016), https://otheringandbelonging.org/the-problem-of-othering/.

- 3 john a. powell & Stephen Menendian, “On Belonging: An Introduction to Othering & Belonging in Europe,” Othering & Belonging Institute, January 2022, https://belonging.berkeley.edu/othering-belonging-europe/papers/on-belonging.

- 4 Baratunde Thurston, “Democracy Means People Power, Literally (with Eric Liu)” https://www.baratunde.com/how-to-citizen-episodes/02-people-power.

- 5 john a. powell & Stephen Menendian, “The Problem of Othering: Towards Inclusiveness and Belonging,” Othering & Belonging Issue 1 (2016).

- 6 ibid.

- 7 Bauer, M., Wilkie, J., Kim, J. and Bodenhausen, G., 2012. Cuing Consumerism. Psychological Science, 23(5), pp.517-523

- 8 Onward, “The Politics of Belonging”, October 2019.

- 9 Loretta Ross, “What If Instead of Calling People Out, We Called Them In?”, New York Times, November 19th 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/19/style/loretta-ross-smith-college-cancel-culture.html

- 10 Donella Meadows, “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System”, https://donellameadows.org/archives/leverage-points-places-to-intervene-in-a-system/

- 11 Fintan O’Toole, “If Only Brexit Had Been Run Like Ireland’s Referendum”, The Guardian 29th May 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/may/29/brexit-ireland-referendum-experiment-trusting-people

- 12 Social Liberal Forum, “Citizens’ Britain: A Radical Agenda for the 2020s”, September 2020, https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/socialliberalforum/pages/3354/attachments/original/1607794003/Citizens_Britain.pdf?1607794003.

- 13 Tim Dixon, “Britain’s Choice: Us-versus-Them or a Bigger Us”, Engine MHP, https://www.mhpc.com/britains-choice-us-versus-them-or-a-bigger-us/.