In 2015 a group of Swedish-Somali mothers came together to organise as mothers against the deadly violence in their neighbourhood and to promote safety by night patrolling and conducting other community-based activities. The mothers live in one of Sweden’s racialised suburbs. Racialisaton (by which a person or place is racialised), I understand as the processes by which individuals and groups are organised hierarchically–with those ‘at the bottom’ implicitly or explicitly attributed negative stereotypical identities based on ideas of race, culture, religion, and ethnicity. In Sweden, racialisation has a spatial dimension. Given many of the country’s multethnic suburbs deal with deadly violence and experience issues around gang-related conflicts, the mainstream media typically reports these areas as unsafe, dangerous, and ‘no-go’ zones. In other words, these are areas presented as intrinsically different and unmanageable, therefore separated from the rest of Sweden. By the same token, the people who live there, largely Swedes with non-Western backgrounds, are often constructed as Others and not quite belonging.

2015 was the year the Swedish-Somali mothers experienced intensified and disproportionate killings of youths of Somali descent. They felt connected to these youths; either by knowing them via their family ties, and/or by being former teachers of the victims. The deaths of these youths are rarely acknowledged or grieved on a national scale. When publicised, the victims and their parents are often blamed for the tragedy through various discourses around crime, race, and (failed) migration. For this Swedish-Somali mothers’ group, the personalised grief of parents, particularly mothers, became a shared grief, which in turn ignited their community-based work. As explained by one mother, “for all the mothers, [the deaths] were very…private, emotionally very close; it can be my child tomorrow, so should I wait till that happens? No, I must become engaged. I must come out.”1 As a reaction to the killings, the mothers formed a group with around 60 engaged women from the ages 30 to 55.

The women’s activities consist of: weekly night patrolling Fridays and Saturdays, cultural and ethnic events for youth, extracurricular activities, monthly meetings for parents, and mothers-only meetings. They also function as mediators between state authorities and mothers; facilitating communication in Swedish for mothers in contact with the authorities, providing information about state authorities and services, and offering financial support for members in acute financial distress (circumventing bureaucratic delays,) to mention a few. Additionally, a significant component of their work is building bridges between the police (who hold a difficult status among the youth in marginalised neighbourhoods due to the historical and continued nature of discriminatory policing) and the youth.

The work of the Swedish-Somali mothers’ group raises several questions around the category “mothers” and the work mothers do. Moreover, it is work that reveals the significance of geography in the dynamics of racial violence. In this paper, I take as a point of departure empirical material from the Swedish-Somali mothers’ group to explore the community-based activities of mothers in the racialised suburbs of Sweden. Though there are other comparable mothers’ groups in the suburbs, I intentionally approach motherwork through the lived experiences of a group - Black Muslim women- too often placed in the margins of knowledge. From a Black feminist perspective, I ask what knowledge these mothers create about motherwork and spatial (in)justice when they are at the centre of analysis.

The concept of “motherwork” is used to make sense of these women’s labour. Motherwork is the labour of mothering,2 and here the concept is expanded to include the community-based activities of the Swedish-Somali mothers. Mothering as a verb offers us a way of thinking about the activities mothers engage in as a practice (a doing), rather than given or natural.

I use “mother” without any assumption of a biological essence. A mother does not need to have a specific gender or biological children to be considered one. Rather, a mother is anyone who engages in the practice of mothering– the meanings we place on who a mother is shifts over time and place, and are shaped by intersecting identities.

The argument that runs through this paper is that the mothers’ motherwork is a form of resistance against othering practices and processes that marginalise the suburbs and those who live there. This is developed mainly in two parts. First, I unpack how the mothers create their own descriptions about the suburbs, and through that negotiate belonging. Next, I examine one aspect of the mothers’ work - their night patrolling activities - as safety-work. In providing other portrayals of the suburbs and its occupants, the mothers expand the space of imagination about the present reality and futures of the suburbs and racialised lives, in ways denied or rendered impossible in hegemonic, mainstream accounts. Likewise, their night-patrolling activities offer alternative forms of justice and community-based solutions for the suburbs, opening up other possibilities for belonging for people and places denied humanity and life.

Nonetheless, before focusing on the specificities of their work, I start by contextualising the mothers and their work with accounts on Black women’s motherwork and Sweden’s racialised suburbs.

Black women’s motherwork

Mother and motherhood, as concepts and realities, lend themselves easily as sites for political, economic, social, and national struggles. They can be important and meaningful identities, particularly for those who engage in practises of mothering. However, issues of mothering and motherhood are often made invisible and/or represented as insignificant to our understanding of social inequalities, specifically in the contexts where mothers or motherhood are depoliticised and naturalised.

Within mainstream western feminist thought, the “mother” has undergone some important transformations through history. Mothering in earlier feminist perspectives was seen as an instrument of oppression and an obstacle to women’s equal access and participation in the public sphere. This has been replaced with theories on motherhood as a social institution and an experience. More importantly, the introduction of the concept of motherwork has provided us with a framework of understanding experiences of motherhood as both varied and specific.

Black feminist thinkers concerned with motherwork reveal in their work how racial domination and economic exploitation shape mothering in different ways. Patricia Hill Collins, for example, argues that centering the experiences of women of colour demonstrates different experiences of motherhood.3

For many women of colour, work and family are two spheres often interlinked. Black women in particular have historically had a unique relationship to labour, specifically in the context of slavery. And in the aftermath of slavery, motherwork as labour continues to mean something different to Black women–especially as divisions, such as private and public, family and work, individual and the collective, are less sharp.4 For Black mothers and mothers of colour, Collins suggests the themes of survival, power, and identity shape their mothering experiences in specific ways.5 For example, physical survival that can be assumed for white and middle-class children, is not a taken-for granted assumption for many racialised mothers.

Another dimension of motherwork, particularly for African American communities, is that of the collective. The work of “community othermothers”, different from biological mothers, that care for children in their extended family networks and the broader community, is significant to the development of the community. Black women’s involvement in the advancement of the community as othermothers forms the basis of a maternal power that is community-based.6 Additionally, this work is a form of political activism that makes significant contributions to establishing a different type of community, in often hostile political and economic contexts.7

I follow the lead of Black feminist thinkers such as Patricia Hill Collins, bell hooks, and Audre Lorde on motherwork, particularly in relation to survival and community, to understand the motherwork of racialised mothers in Sweden’s suburbs. These thinkers emphasise in different ways the relevance of community for the motherwork of Black and other racialised women. They also demonstrate how spatial and other forms of violence shape the conditions of motherwork for racialised mothers.

This is clearly demonstrated in the racialised suburbs in Sweden. Looking momentarily at the suburbs in Stockholm and comparing them to other areas in the city, these are places with weaker performing schools, segregation, growing poverty, and long-term unemployment. The conditions of these places make it difficult for parents not to be concerned about the survival of their children in a different way than parents living in other areas. Furthermore, the collective and communal element of Black women’s motherwork reflects the motherwork of the Swedish-Somali mothers. The mothers’ social and political participation in their neighbourhood is part of their motherwork. It is a collective and community-centric type of motherwork, impacted by the realities of racism, economic difficulties, and class oppression experienced in their neighbourhood.

The motherwork of these mothers is particularly shaped by the ways the suburbs are racialised–it is also shaped by their own experiences and knowledge of their geographic space. Hence, we cannot make sense of their motherwork without considering the relationship between their work and space. In order to comprehend this correlation, we need first to understand how Sweden’s suburbs have become racialised, an othered geography.

Sweden’s racialised suburbs: othered geographies

Sweden has long been recognised internationally as representative of tolerant multiculturalism and progressive and inclusive politics on issues ranging from gender equality, to welfare policies, to migration politics. What we see today in Sweden, however, are the effects of a neoliberal reconstruction of the welfare state where issues of citizenship, identity, and belonging, have become central in public debates. These issues have developed alongside shifts on the political landscape. Currently, Sweden’s third largest political party is the far-right Sweden Democrats, whose success can be attributed to the party’s singular and xenophobic focus on migrants and migration. At the same time, these shifts have left effects on the physical environment, striking Sweden’s racialised suburbs particularly hard. These residential areas are often characterised by material collapse and racialised poverty, with a high concentration of inhabitants with migrant backgrounds from Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

The Million programme, a Swedish public housing project that was developed in the 1960s and 1970s, was meant to provide affordable housing constructed to a good standard. Despite its aim of providing new housing options to a growing working class population lacking housing options in urban spaces, it resulted rather in racialised and segregated suburbs. Even from the project’s inception, the areas included in the programme have never been seen as truly belonging in the nation. Consequently, they have remained of recurring interest to mainstream media, the state, and local governance. Representation of these areas has undergone several ransformations as the demographics have shifted from predominately (white) working class to (non-white) migrants.

Processes of othering

Before the construction work on the Million Programme was done, the expectations of modernity that had initially surrounded the project were replaced with discourses of dirt and filth in mainstream media.8 By the end of the 1970s, crime and social problems were at the centre of media reports, becoming permanent features in the characterisation of the suburbs as problem areas.9 The last important element was the issue of the “migrant.” Though migrants have always been part of the historical stigmatisation of the suburbs, in the beginning of the 1980s, they shifted from being perceived as threats to becoming the problem.10 By the 1990s, colonial rhetoric was used to describe these places as exotic, different, unmanageable, and dangerous, placing them and those who live there outside the Swedish landscape.11

Considering these discourses, researchers influenced by postcolonial theories urge us to acknowledge the continued presence of colonialism, racism, gender, and class oppression–and their intersections in how the suburbs are depicted.12 However, the colonial rhetoric is not limited to the media, but is reflected in state policies regarding, for example, the housing sector, the labour market, and education.

Recent dynamics in the representations of the suburbs are shaped by a declining welfare state and investments in neoliberal economic policies. Neighbourhoods that form part of the Million programme consist of housing in urgent need of renovations; yet renovations of privatised public houses end up with unaffordable excessive rent increases. Simultaneously, these places experience higher levels of poverty and unemployment. Alongside the material difficulties, they are places with heightened surveillance and policing, where the inhabitants, predominantly people with migratory experiences, are routinely subjected to checks and stop-and-search.13 The criminalisation of the racialised suburbs and its people, particularly the youth, is reflected in policy developments around gang violence and security, which has resulted in increased police and security guard presence in many of the suburbs.

To counter the stigmatisation, countless forms of resistance have emerged from the suburbs: organised and spontaneous, formal and informal, individual and collective forms of struggle over representation, dignity, and the material wellbeing of the inhabitants of these areas. Issues such as segregation, racism, and state violence are addressed through poetry, films, music, organised talks, and demonstrations, to mention a few.

However, both academic research and mainstream media accounts of resistance in the suburbs present a dominance of youth organisations and movements. This is an unsurprising effect of the overbearing interest by the state and mass media on the suburbs’ youth. There are, nonetheless, several groups organising around similar issues as the (more well-documented) youth. This includes parents’ night patrol groups, community gatherings, organised demonstrations led by mothers against deadly violence, and activities within ethnic-specific associations, providing children with cultural resources to foster a sense of self-esteem as part of battling racism.

Parents’ social and political organising, particularly that of mothers from these areas are often read in relation to their children, the youth. This means that with the description of the “violent” behaviour of the youth in public debates, parents are often blamed for inadequate and deficient parenting. With the logic of “bad” youth and “failed'' parenting, mothers taking the streets, for example, to protest deadly violence are framed primarily as mourning mothers, rather than citizens with political claims. Those coming together to organise for the safety and wellbeing of their children and neighbourhoods are seen principally as extending “natural” mothering to public spaces or as managing disruptive youth. In the examples above, mothers are depicted in ways that detach them from political agency. But what does it mean to centre the activities of mothers in the suburbs beyond the limitations of a naturalised mother-child relationship? Looking closely at the work the Swedish-Somali mothers engage in, it is difficult to limit their activities as solely care-work. In the following section, I focus on the knowledge the mothers create about the suburbs by offering other narratives about the place, and negotiating belonging in ways that challenge hegemonic depictions of these areas.

Other narratives of the suburbs and its people

The dominant representation of the racialised suburbs as dangerous and crime-ridden places, and the realities of economic oppression, transform them symbolically into uninhabitable places. The suburbs are portrayed as external to the nation. Those who live there are Othered as not really belonging within imagined ideas of “Swedishness”: white, Christian, and liberal, with lives devalued and deemed as disposable and risky. This becomes very apparent in how mainstream media and politicians approach these areas and the people who live there.

During in-depth interviews with the mothers, one political proposal was addressed repeatedly as an important example of the negative representation of the suburbs. In 2017, the conservative political party, the Moderate Party, proposed a bill to send the military to fight gang and other criminality in “particularly vulnerable areas” in Stockholm. Vulnerability is a term used by the police to describe a geographic area with low socioeconomic status and influence of criminals. The far-right Swedish Democrats have repeatedly suggested in debates the need for military presence in the suburbs and the incumbent Social Democrats have opened up to the possibility of the proposal becoming a reality.

For the mothers, these proposals around crime and violence refer directly to the youth of the suburbs (even more specifically: boys and young men), though often masked as proposals to fight gang criminality. Within the discourse of gangs is the incrimination of all the youth in the suburbs as potentially violent. The women experience the proposal as being about their children, and as communicating something specific about their neighbourhood in ways they do not recognise.

The military is normatively understood as protecting the state and its citizens from external threats. So, what does it then mean to have the military at work within the internal boundaries of the nation? In the bill and in the political suggestions from politicians, the military is merely instrumental–a force to control a place and people that are unmanageable. In this case, the normal order for legitimate exercise of violence and control by the state – the police – is insufficient, hence requiring extraordinary measures. For one of the mothers, Sahra, the extraordinariness also renders those who live there as abnormal, outside humanity; “It makes it seem like we are small animals that can’t take care of anything”, she explains.

The representations of the suburbs embedded in the proposal and other media depictions are perceived by the mothers as inaccurate. They are assumed to be wrongful narratives that can only be produced by those standing outside and gazing from above. By visiting the suburbs (stepping in), Sahra argues that “there’s life”, and Hodan, another mother, suggests that a closeness also provides knowledge about the motivation behind the actions and grievances of the youth, explained by the youth themselves.

In opposition to the negative representations, the women provide other accounts of their neighbourhood. In creating other knowledge, they are specific in what they choose to share about their area. The less positive aspects of the place and material difficulties are not centralised. It is not because the negative does not exist, but there is so much more that forms part of their daily realities, yet rarely gains public interest. They want “us”, that is, those who do not live in or are not associated with these racialised spaces, thus not belonging to the place, only to know specific things about their area. It is an active place with activated citizens, contrary to the strong stigma depicting the suburbs as passive, welfare cases and rife with criminality.

The women stress that people who live in their area have jobs and are in higher education. The mothers that take part in this study are themselves illustrative of active (model) citizens. They all work either within the school system or in the municipality; two are university students, while also being engaged in non-paid community work. As working citizens, the women also challenge racist assumptions about Somali women often portrayed in the media as “welfare mothers”, incapable and unwilling to occupy non-traditional jobs beyond the private realm. However, though the women’s active and activated lives are not illustrative of the realities of every inhabitant in the suburbs, particularly as places with higher proportions of unemployment, by activating the suburb, the women infuse the place with life, in contrast to the dominant depictions of passivity and apathy.

“This is home”: negotiating belonging

Another way the women challenge negative accounts of their area is through their connection to the place. The women talk about their neighbourhood with sentiments of love, emotionality, a strong sense of responsibility, and a feeling of embeddedness within place. This relationship to their area is partly influenced by the fact that all the mothers have experienced essential parts of their life processes there, including the development of their identities as mothers. Some of them moved to the place in their formative years, as children or teenagers, but all have given birth and cultivated lives there for many years.

Despite the descriptions of these racialised suburbs in mainstream media and by politicians as “failed” and “doomed” spaces, these areas offer a possibility for negotiating belonging for those who live there. The significance of place for the identity-formation of youth in marginalised areas has for example been well-researched.14 From this research, the common argument is that the stigmatisation of the suburbs creates a specific relation to the place. This in turn becomes an important component of an individual’s sense of identity and how they navigate belonging.

For many of the mothers, their neighbourhood is “home” and none of them have plans of moving away. It is a place where a sense of belonging has been developed. One of the mothers, Faduma, explains her unwillingness to move away from her neighbourhood as it would take her away from the “warmth and hugs, and smiles [she] receives everyday”. Faduma explains her sense of belonging as stemming partly from never being asked where she comes from when in her area–a question often asked to visibly racialised persons in other parts of the city. This question has the effect of disrupting the sense of belonging that comes through feeling “at home” as it clearly marks them as foreigners.

In her area, everyone is from somewhere. “Home” does not have one definition; rather it is an expansive concept that allows people from multiple ethnicities to experience it in multiple and complex ways. The inhabitants of the suburbs, in their home areas, are able to form ways of relating to place and develop belonging in ways that may not be available to them outside the suburbs.

The experiences and perceptions of home can be traced in the women’s descriptions of the place as filled with beauty, community, familiarity, conviviality; tragic things do happen there, just as everywhere else. Some of the mothers exemplify their belonging to the suburb by shifts in their comfort levels as they navigate other areas of the city. As visible Black Muslim women, many of them describe feeling more comfortable in the suburbs where many more people share similar identity markers along with experiences of the place, than in segregated white and rich neighbourhoods.

Belonging for these women also involves the possibilities these racialised suburbs hold (even within structures of racial violence). For Faduma, her area is a “multicultural global promise”:

[You can] eat kebab, eat rice, eat whatever you want. We have it all here. You don’t have to go to Turkey to eat kebab. We have pizza Italy here, you know. One could have presented this place with pride, instead of just showing burning cars, every time [...] [my area] is mentioned. That’s what I hate the most. Instead of showing the nationalities, the global village, burning cars [are shown]

Faduma draws on the language and dreams of a multicultural society. She describes her area as a global village within the city, to evoke ways of living positively with the plural differences present. This is the same multiculturalism that has increasingly become known as the source of violence, seclusion, segregation, and parallel worlds, particularly in relation to the suburbs. It is a multiculturalism that has been vilified as hindering those with migrant experiences (from outside the West) from fully belonging. Yet, I want to suggest that Faduma articulates a positive version of multiculturalism; for her, the global presence in her neighbourhood is a sign of productivity and capacity to live with difference that facilitates her belonging to her area. The global village sets a framework for belonging where difference is not an issue, rather a possibility or even a source of pride as evident in Faduma’s account. It is clear from this section that the (counter) knowledges the mothers create about the suburbs and belonging are grounded in their lived experiences and relationship to the place. A similar relation to and knowledge of their area influences the community-work they do. What follows is a closer look at one aspect of their motherwork, in particular their work based on promoting safety in their neighbourhood.

Redefining safety-work

As the mothers’ group was initially formed to address the insecurity in their neighbourhoods and killings of youth, safety-work is a key component of their motherwork. Their night patrol activities are explicitly targeted at promoting safety. The women explain the violence and deadly killings in their area as stemming from broader structural and institutional gaps: failed school systems, lack of real job opportunities for teenagers and young adults that finish upper-secondary school (principally those graduating without pass grades), insufficient or underfunded extracurricular activities, and self-fulfilling prophecies (expectation that children from the suburbs will end up in criminality propels some in that direction). This knowledge of the realities of the space, and the commonality of experiences as mothers, have shaped the formation of the women’s group and community-based activities. However, there are different understandings of safety and security in the suburbs depending on who is asked, and where they are located.

Varied interpretations of safety

The women explain their sense of safety as directly related to the fact that they live in the neighbourhood. They reaffirm this by sharing how late they can walk in their area alone without fear, and how youth (who might be criminalised by “outsiders”) greet them and offer to follow them home at late hours or with groceries. Those who often feel unsafe in their area, they argue, are people who do not live there.

The state on the other hand relates to safety and insecurity in the suburbs in a different way. With terms such as “particularly vulnerable areas”, “vulnerable areas”, and “risk areas”, the police identify and distribute risk hierarchically across various geographic areas in Sweden. The areas described in these implicitly negative terms capture many Million programme suburbs. In the autumn of 2019, the Social Democratic government proposed the largest package so far to fight gang criminality, after a series of publicised gang-related killings. In the 34-point programme presented, there is a clear emphasis on sanctions and harder punishments to impede gang criminality and violence. Only eight of the thirty-four points are reserved for preventive measures, which communicates the the current government’s top-down approach to dealing with issues of safety and security.

The State allocation of resources is relevant to the women as they make sense of the current situation of insecurity. In terms of state investments in increasing policing as solutions to gang criminality, the women are particularly critical about the upsurge of security guards in the area–to which they refer as misallocated funds, actually worsening criminality and feelings of insecurity. For a few of them, the disproportionate budget for policing (increase of security guards) as compared to the budget for education in the area demonstrates an expectation that the children living in the area will not make it academically. Focusing on policing is an investment in criminality: “They have already decided. There will not be high investments in schools as they [the children] will not make it here. They will find themselves as criminals, so let’s build that up…You can see that they expect us to be criminals.”, Maryam argues.

Maryam suggests that external expectations of criminality are in turn internalised by children and youth growing up with beliefs of themselves as problems. Instead of allocating funds to more police and security guards, the women suggest the money can be of better use: improving the schools, increasing the funds for youth centres and extracurricular activities for children, keeping the area well-lit during the nights, and increasing the funds for associations so they can properly cater for children. “I think every guard costs quite a lot in monthly salary. Our kids cost less”; Faduma rationalises.

The women themselves are perceived by other community members (particularly the youth and children) as symbols of safety, influenced by social and cultural norms around mothers and motherhood, how they identify and are identified by others as community members. Additionally, in the role of mothers, they occupy a specific position in their own Somali ethnic community as leaders and the most important persons in the lives of children. The sociocultural expectations of mothers must often be navigated and negotiated. For these mothers specifically, they see themselves as responsible for the education, well being, and cultivation of children. The burden and obligation of the responsibility are not lost on them. However, it is an assigned role that helps them establish a specific relationship to their blood and community children and youth. There is a respect associated with the symbol of mothers, which the women strategically use to establish a relationship with children and youth (regardless of ethnicity) in their work. Nevertheless, mothers, and parents in the suburbs in general, are often blamed by the personnel in schools and social services, police and civil servants, as contributing to youth unrest and criminality.15 While within their own communities and close networks, they may also be blamed for failing to properly raise children away from drugs and crime.

Safety-work in practice: collective mothering in the public

The women share how they were seen as responsible for the deadly shootings in 2015 by fathers. Given their assigned responsibility (as mothers) for youth that were themselves seen both as actors and victims in the violence, the women were held partly accountable. At the same time, the mothers’ greater charge for children and their well-being, along with the close presence of loss, influenced their decision to take to the streets.

Though the women all experience feeling safe in their neighbourhoods, they describe public spaces as potential spaces of danger for children and youth. It is the lack of control and the notion that anything could happen out-there (which also includes discriminatory practices by the police, which can unfairly target their children), that make them worry about their children being outside the home. The public space is important to the sociality of youth and is a space very few parents can practically and completely restrict their children from as they grow older. Thus, for these mothers, there is a need to change the spaces from potentially unsafe to safer, particularly for young children who have yet to demonstrate a greater interest in spending time outside by themselves, an interest they saw as inevitable. The children moving to the outside requires the parent to act similarly.

Engaging in a form of collective public mothering, the women relate to night patrolling in strategic and pragmatic ways, they talk about how they approach youth in a different manner than the police and other state representatives. They demonstrate an awareness of how their bodies are read when they are patrolling. When the women are identified as mothers, children and youth interact differently with them than when alone with their peers w. Furthermore, those conducting activities (such as drug selling) not meant to be seen or heard by parents and other unconcerned adults, are disturbed by the mothers’ conscious presence at unusual hours in spaces not normally meant for parents.

The mothers take advantage of how they can be perceived as disruptive of the normative order. However, they are also very adamant that their presence is not seen as policing, surveillant, or disciplinary. For example, the mothers move around in different small groups of maximum four mothers to avoid evoking fear. This stands in strong contrast to police operations, where safety is connected to large intense presence in neighbourhoods. Further, they draw on existing relationships they have with the youth and children and sociocultural norms attached to mothers, to build new or strengthen existing relationships. They put a lot of effort into trying to engage with the children from their perspective and in a playful and participatory manner, instead of the normative parent-child hierarchy.

Moving around their area with them, I observe how they put these strategies and tactics into practice. For example, as the mothers have identified building relationships primarily with the youth when night patrolling as a significant strategy for their work, they make sure to greet the youth and children they meet on their patrol and establish an acquaintance. “People think we go out and then everything is calm. No, this is building relationship with the youth, and then the day he or she does something stupid, the chances are big that they will listen to us[mothers], instead of the police who arrives fifteen minutes [later].”, Faduma explains.

Thus, visiting youth centres with the women, I observe how some of them stay to speak a bit longer with the youth they know, while others engage in games that are being played. If they come across young children outside at late hours, rather than strictly telling the child to go home, they curiously ask the child whether they are afraid to go home by themselves and offer to walk them home. Though expressing love and care for the community’s children and youth through playfulness does not erase the difference in power dynamics between parents/adults and children, the mothers’ conscious methodology provides another meaning around safety and security.

Implication of the mothers’ safety-work

From the mothers’ work, it is evident that safety stems from community experiences and relations. The State and the mothers (inhabitants of an area) have different roles and responsibilities in contributing to community safety. However, with the mothers centring relationship-building and care, over surveillance and disciplinary approach of the state, they provide alternative options to security. Further, they offer an understanding of what safety in stigmatised communities can mean when formulated by community members themselves.

The women’s community-centric safety-work has implications on how the youth and the suburbs are perceived. Firstly, by showing youth and children care in ways not always readily available in the State’s security procedures, the mothers convey a particular description of the youth–as simply youth. This is in contrast to the dominant portrayal of this group as unapproachable, dangerous, and unpredictable, in criminalising and dehumanising discourses. As one of the mothers proposes, speaking to the youth and children will provide State authorities and the local government with solutions to grievances. “Treat them as children, as youth, as humans, and you would find out.”, Hodan advises. With the mothers’ approach to safety and security as grounded in human-based interactions and relations, they also contribute to shifting the understanding of their area and other racialised neighbourhoods as places where life can thrive, even within structures of racial and economic oppressions. They offer us ideas of alternative justice and community-centric solutions, and a future for the suburbs.

Nevertheless, the mothers face challenges in their work. Up to today, despite the role and responsibility the women take in their community to deliver welfare, and in many cases, arguably replacing the role of the State, the women’s work remains on a voluntary basis and unfinanced. They struggle to get the city council to take their (largely praised) work seriously and recognized as real (productive) work. The effects of long-term unpaid labour require the women to constantly negotiate between family work, community work, and their paid work. Another challenge the women face is practical support. At the top of their agenda is to get a physical and permanent place for them to meet and organise, as well as conduct some of their activities. A need the city council has failed to meet. Their work continues to be seen as largely “natural” mothering and, by extension, is erased from its political significance.

Conclusion

In this paper I have centred the motherwork of mothers committed to improving the conditions of life and the representation of their neighbourhood in the racialised suburbs of Sweden. Their work offers insights into the dynamics of othering and racial violence that are embedded in our lived environment. The suburbs are racialised because of those who live there; and the residents of the suburbs are Othered because they live in a racialised space. At the same time, it is an important place where residents can navigate belonging without the limiting and ever-shifting boundaries that form “Swedishness'' as inherently white and Christian. Yet, what does it mean for a mothers’ group that is marginalised due to categories such as gender, race, religion, and nationality, to work against the injustices in a city? I would like to highlight a few points about the mothers’ work that I argue are important for further consideration and exploration when addressing racial violence and spatial (in)justice.

Firstly, the women demonstrate and position themselves as knowledgeable agents in their area, developed from being in and of the place. They know the realities of the neighbourhood and also what is needed to enhance safety and promote dignified livelihoods particularly for children and youth. However, though they are valuable community resources, they find themselves deprioritised and unconsidered, unasked to impart their knowledge for positive improvements in their area. A silencing and subordination of the mothers that finds resonance in the long tradition of the marginalisation of the gendered subaltern subject. It is a silencing that ignores the agency of the women and other inhabitants of the place. Nonetheless, it directs our attention to what transformative work in marginalised communities should look like (and continues to be the dominant demand from many from these communities)– as work led and defined by community members for the community.

Furthermore, the mothers’ work opens up reflections around citizenship and the gaps within the welfare state that require our attention. Their work reveals the grey zone between the delivery of welfare by the state and civil society; the mothers are in fact providing significant aspects of welfare. In their safety-work, they engage in practises that ensure the safety of their community in ways that centre community well-being. They represent state authorities in realms they are perceived as lacking. By providing essential information about social services delivery and the role of social workers, the women facilitate other inhabitants’ access to citizenship, particularly by informing them about aspects of rights and obligations embedded in the content of formal citizenship. The women assuming the role of welfare providers leave us with questions about the state. Where is the state?

The effects of a neoliberalising state, shifting towards neoliberal economic policies at the cost of deflating and disappearing welfare budgets and placing greater emphasis on individualism have had dire effects on the suburbs. Nevertheless, the mothers exemplify something different in their work. By temporarily occupying the role of the state (and becoming more than citizens in their community-centric activities), they communicate a more ideal state-citizens relationship than what currently exists in the suburbs due to neoliberal politics. That is, a relationship based on closeness (e.g., visibility of welfare services and investments reflected in the needs of inhabitants), willingness to understand the conditions of life in the suburbs, and a care approach where the current alienation and disregard for human life can be altered.

Author bio:

Jonelle Twum is researcher, cultural producer and filmmaker who explores various range of questions through the perspectives of minor and disregarded figures of history from a Black feminist perspective. Twum is also the founder and artistic director of Black Archives Sweden.

Artist bio:

Alaa Alsaraji is a visual artist, designer and creative facilitator. Through her creative practice she aims to explore themes such as belonging, reimagining space and community, predominantly using the medium of digital illustration. She also works as a facilitator, delivering creative workshops. Alaa is also the arts editor of Khidr Collective.

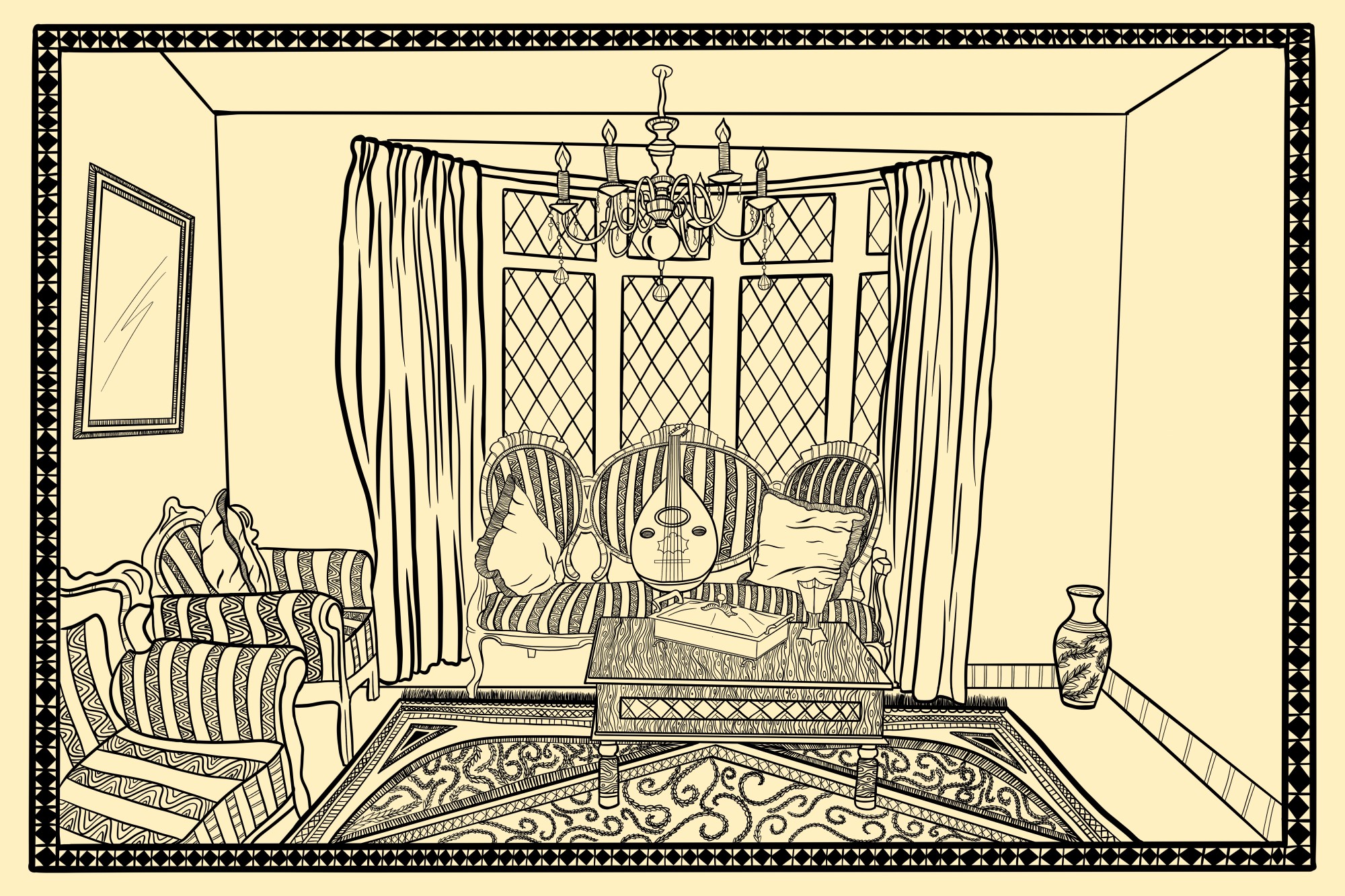

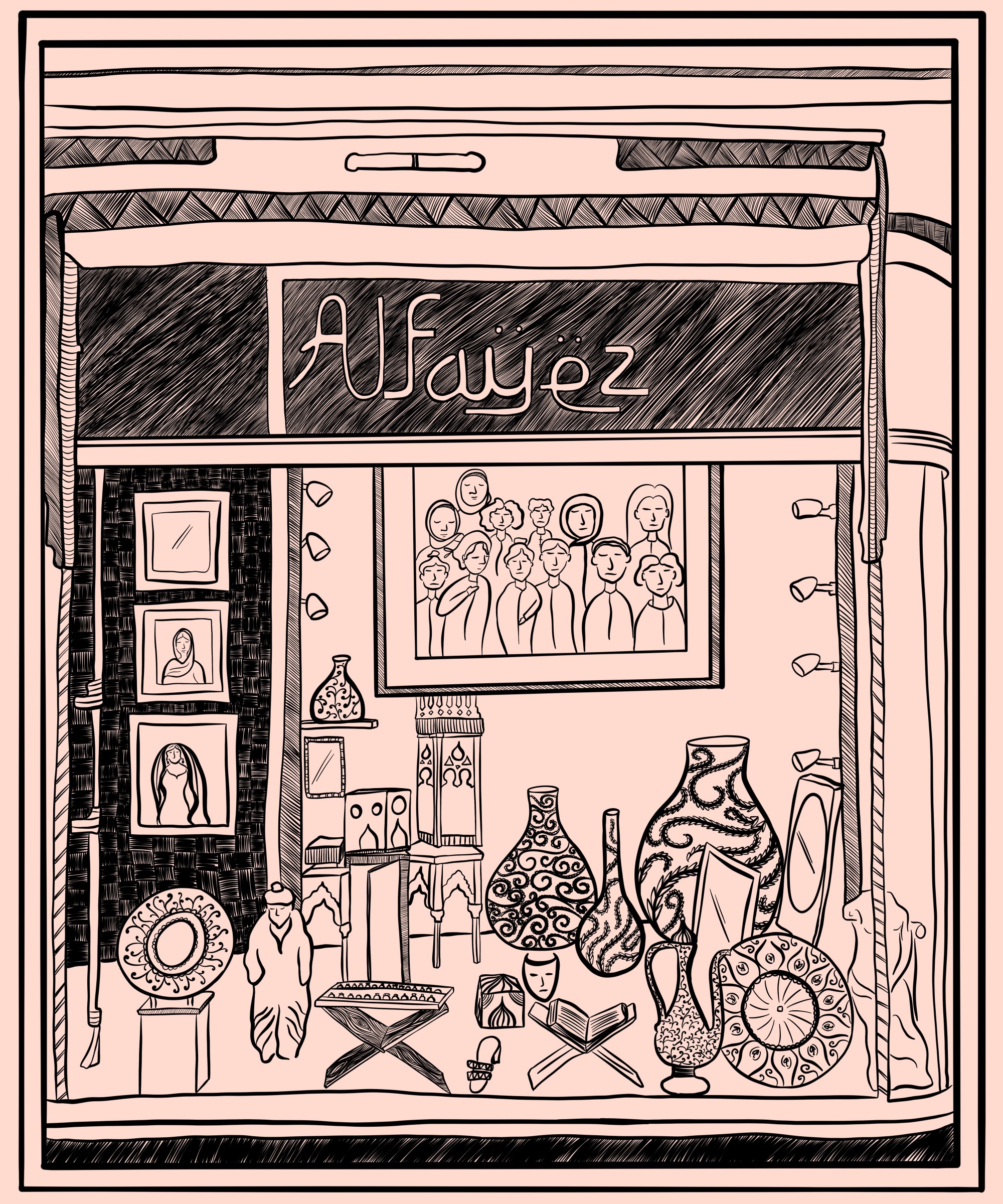

Art Description:

With rising Islamophobia, fuelled by hateful media rhetoric, State surveillance and the criminalisation of Muslim communities, our families and communities often feel unwanted, targeted and both physically unsafe and socially isolated, cautious to fully be ourselves and embrace our heritage and faith within British society. Despite these external conflicts, which have expanded over generations, communities have established and maintained their own safe havens, often improvised and built out of necessity, these spaces create a sense of belonging and safety. ‘Mapping Sanctuaries’ is a digital illustration and audio series highlighting the spaces that British Muslims from different backgrounds have created or ‘carved out’ for themselves, enhancing a sense of belonging and ultimately creating a sanctuary from the realities of life as British Muslims.

These images selected here from the ‘Mapping Sanctuaries’ series correspond to stories shared by British Arab and Black Muslim women on their experiences within an often hostile and isolating society. ‘Mother’s Living Room’ in particular reflects on how our ‘mothers’ navigate their multifaceted and complex identities between public and domestic settings.

- 1 All the interviews were conducted in Swedish and all translations to English are mine.

- 2 Andrea O’Reilly, Matricentric Feminism: Theory, Activism, and Practice (Demeter Press, 2016), 1.

- 3 Patricia Hill Collins, “Shifting the center: race, class, and feminist theorizing about motherhood,” in Mothering: Ideology, Experience, and Agency, eds. Evelyn N. Glenn, Grace Chang, and Linda R. Forcey (New York. London: Routledge, 1994), 46.2

- 4 ibid., 47-48.

- 5 ibid., 61.

- 6 ibid., 56.

- 7 ibid.

- 8 Urban Ericsson, Irene Molina, and Per-Markku Ristilammi, ”Plats Järvafältet,” in Miljonprogram och media: föreställningar om människor och förorter, eds. Urban Ericsson, Irene Molina and, Per-Markku Ristilammi (Integrationsverket & Riksantikvarieämbetet, 2002), 18.

- 9 ibid., 18.

- 10 ibid., 19.

- 11 Irene Molina, ”Koloniala kartografier av nation och förort,” in Olikhetens paradigm, eds. Paulina de los Reyes and Lena Martinsson ( Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2005), 113.

- 12 ibid., 115.

- 13 Aleksandra Ålund, Carl-Ulrik Schierup, and Lisa Kings, "Reading the Stockholm Riots – A Moment for Social Justice?," in Reimagineering the nation: essays on twenty-first-century Sweden, eds. Aleksandra Ålund, Carl-Ulrik Schierup, and Anders Neergaard (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2017), 333.

- 14 see Mustafa Dikeç, Badlands of the republic: Space, Politics and Urban Policy (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007); Irene Molina, “Identitet, norm och motstånd - ungdomarna i förorten” in Bortom etnicitet: festskrift till Aleksandra Ålund, eds. Diana Mulinari and Nora Räthzel (Umeå: Boréa, 2006), 183-192.

- 15 Magnus Dahlstedt and Vanja Lozic, ”Lokalsamhället och gemenskapen – viljan att samverka” in Förortsdrömmar: ungdomar, utanförskap och viljan till inkludering, ed. Magnus Dahlstedt (Linköping studies in social work and welfare: 3 (2018)), 221.