For over 40 years in a row Denmark, a small country in the north of Europe, has been voted as one of the happiest countries in the world by the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). Countless articles and books have been written as to the reason why. It’s not the weather or the taxes, so what gives?

After many years of research, personal and professional experience, we believe that one of the secrets to their success is found in the way they raise and educate their children. In particular, the Danes’ focus on something called fællesskab, and its incredibly powerful effect on societal wellbeing.

Fællesskab, directly translated, means “community” or “togetherness”. Essentially, it is the feeling of belonging we get when we feel part of a meaningful group. There is a deep sense of happiness that comes from social connection and the Danes have known this for a very long time. This is why faellesskab is such a huge part of their culture and education.

In Denmark, there is a major focus on something called “trivsel” (treevsel) (thriving/well-being). Having high “trivsel” is by far the most important goal for parents and teachers. It is believed that academic ability will follow when well-being is sound. As the saying goes: you can’t learn well if you don’t feel well.

Schools take trivsel (wellbeing) so seriously that one of the most important national standardized tests taken by all students and teachers every year is called a trivsel test. This test is completely independent of academics.

The questions, for example, could be: “do you feel seen and heard?”, “do you feel helped when you feel sad or upset?”, “would you help a classmate who looks upset?”. The important thing is for children to be aware, not only of their own wellbeing, but to think about the wellbeing of the group.

Interestingly, Danes have found that one of the biggest factors affecting trivsel (happiness) in schools is the quality of the faellesskab. In an analysis of over 300,000 participants in a 2016 Danish Prosperity Survey, the results showed that wherever there was a high level of fællesskab (togetherness), it positively affected every single facet of well-being: from school drive, to improved learning, to better involvement, competence levels, and increased peace of mind.

We never think of community and belonging as something to learn, but in Denmark, it is a fundamental part of education from the time children are very young.

Teaching Fællesskab; Giving up the “Me” for the We”.

There are two kinds of fællesskab. One is the fun kind that flows easily. Some might call this “hygge” (cozy time). This could be that feeling of belonging that comes from playing a fun game, having tea and cake together or collaborating well with people we get along with. We are effortlessly part of the group and it’s pleasant, and cozy.

The other kind of fællesskab is the belonging we get from making an effort to be part of the group even if we don’t necessarily want to. This is called “forpligtelsesfællesskab” or “obligated togetherness” and it is the belonging that comes from making an effort to collaborate. It’s a subtle difference but an important one. Forpligtelsesfællesskab is learning the value of “we time” rather than “me time” and giving up a piece of myself for the whole.

“You have to give something to receive something from the fællesskab,” says Kasper Nyholm, the principal of Absalon Skole, which focuses closely on forpligtelsesfælleskab, or responsible togetherness. “Maybe you aren’t getting all what you want in your own way, so you have to make some changes to compromise. Humans are social animals. It takes work to rely on each other, and sometimes that means doing things a little against your own wishes.”

A core value for the Danes is equal dignity. They pride themselves on having a flatter hierarchy where everyone can feel respected no matter who you are or where you come from. This is not always easy to achieve, of course, but this hierarchical approach is one of the interesting new ways Danes are tackling othering1 and bullying in schools.

They don’t believe that bullying comes from one or two bad children, but bad group dynamics driven by our deep-seated human need to belong. Rather than blaming the individual or the group, they work to improve class unity, tolerance, and empathy instead.

From the age of 6-16 Danes are taught empathy in the classroom at least one hour a week in the form of something called The Class' Hour. Play is considered one of the most important activities a child can engage in due to the natural learning and social skills it teaches. Schools regularly host togetherness gatherings (faellessamling) to improve belonging and teachers keep a constant gauge on the quality of the group dynamics.

Make no mistake, Denmark is not a utopia and their battles with othering are very real. They contend with many socio-economic and racial internal issues just like any other country.2 However, the innovative approach they take towards belonging appears to be working. In 2019 alone, Denmark had one of the lowest rates of bullying in Europe. It is also voted as one of the most empathic and trusting places in the world.

We are living in a very particular moment in history. The pandemic has shattered many norms and beliefs about “the way things are”. We will most likely never again have the possibility for a fresh perspective in the same way.

Why not try on the lenses of one of the happiest countries in the world–why not ask ourselves: is there anything we might consider doing differently in our own culture to foster more faellesskab?

The Rise of Survival of the Friendliest

From the beginning of time, we have needed each other as humans. We rely on social groups for survival. We evolved to live in cooperative societies. Being excluded is extremely painful. And yet, so many countries have woven their cultural fabric out of the idea that survival of the fittest, a mentality based on self-interest and individualism, is the best way. When you consider how we evolved as humans, it’s curious that this way of thinking has been so dominant in so many places.

Evolutionary anthropologists are now focusing more and more on the concept of survival of the friendliest. Humans evolved after all, not because we had fangs and claws, but because we could cooperate and collaborate. Successful people don’t operate alone; each of us needs the support of others in order to achieve positive results in our lives. There is a quote that says “when you replace the “I” with the “we” even illness becomes wellness. This is the fundamental belief underlying the word “fællesskab”.

In Denmark, fællesskab is one of the most important values of their society. It is a collection of people that are bound together by something they share in common, something they agree with, have the same view on, or an interest they share or do together.

Fællesskab can be seen in all aspects of Danish life, from foreningsliv (“association life”) which are groups of people formed around different hobbies or interests–from the classrooms, to the workplace or family life.

The issue in other cultures is that, while we think about the wellbeing of our children, we rarely think about the wellbeing of the group and what effect that has. In Denmark, this focus on the group is seen as absolutely fundamental to the wellbeing of the individual. Their entire educational system is structured on this. Danes believe children need to learn to think about others too, not just themselves. This is how we create a better society.

“Remember, we need to take care of each other” is a very common phrase one hears in a Danish classroom. This is quite a different approach than mainly striving to be the best or survival of the fittest. Their society lines up much more with survival of the friendliest.

In fact, the meaning of education in Danish is made up of two words; “uddannelse” which means teaching academics and “dannelse” which means teaching how to be a caring and responsible citizen. The two are completely intertwined in what it means to educate a child and seen as equally important for the curriculum.

Teaching Empathy; it’s a piece of cake

One of the most significant places they work on improving fælleskab and teaching empathy is in something called the Class’ Hour. “Klassens Time” is set for a special time once a week. It can be any day of the week, but it is a core part of the school curriculum. It stretches from the first day of school from when they are 6 years old up until the last day of school at 16 years old. The class’s hour is so normal for Danes, they don’t even see it as special.

The purpose of the class’s hour is for all the students to come together in a comfortable setting to talk about any problems they may be having and discuss them. Together, the class tries to find a solution. This could be an issue between two students or a group or even something random.

“I remember when we were 10 or 11 we often talked about girl cliques.” says Anne Mikkelsen, a Danish high school student from Struer. “That was a common topic and we would discuss it and try to solve it together. Sometimes that just meant being more aware and trying to blend in with others, but it always helped us to talk about it together."

“The important thing is that everyone is heard.” says Jesper Vang, a middle school teacher in Odense. “Our job as the teacher is to make sure that the children understand how the other feels and see why the other feels as they do. This way we come up with a solution together based on real listening and real understanding. It isn’t about someone being right or wrong. It’s about making sure the other person feels heard and learns to listen.

If there are no problems, then the students just come together to relax and “hygge” or cozy around together. They often eat cake or foods they choose together and play games to have fun and improve unity. The Class’ Hour cake even has its own recipe.

While it isn’t clear what gets discussed each week, it is clear that the Class’ Hour is teaching empathy and helping students learn the social skills based on respecting and understanding others and their own feelings. It is facilitating social connectedness rather than division.

The point is that Danes see this time as crucial, not optional. It isn’t just about solving conflicts, it’s about being together in a non-academic way. This could be planning outings or playing games or talking about how they would like the atmosphere of the class to be. These experiences naturally build up good stories about the class and this fosters better faellesskab.

Building Belonging: it’s as easy as child’s play

Recess is another key place where Danes work on improving community and collaboration. Play has been considered in educational theory in Denmark since 1871. It’s one of the most important activities a child can engage in. While play has slowly been stripped away from many cultures in place of academics, it’s now being recognized around the world for its proven importance in teaching skills like: negotiation, empathy, creativity, self-esteem, resilience, and many others.

Teachers in Denmark pay close attention to what happens on the playground so they can discuss it with the class afterwards often in the Class’ Hour. Based on their observations in play, teachers might ask younger children to switch friends for a week during recess to practice being with different classmates.

The teacher organizes it with the children in advance and tells them who they are assigned to play with. They may even decide together what games they will play so they don’t have to choose, which makes it easier to be together. The children aren’t forced to do it, and they talk about it if it’s too difficult for them, but this is part of education. They must learn to be with others, and this starts young.

Children often make wonderful discoveries going outside of their comfort zones and working or playing together with someone different. These kinds of activities build up courage, tolerance, empathy, and resilience.

“It isn’t always easy to come into the fællesskab” (or togetherness) says Kasper Nyholm “You may not want to collaborate, or listen to someone or compromise to play together, but this is all part of what we must learn to be in a community. We want students to learn to take part in giving up some of themselves for the whole.”

Just because we are different doesn’t mean we can’t all run the pirate ship together or play fire fighter or collaborate and help each other. Just because we are different, doesn’t mean we can’t share a purpose and respect each other and have fun. The importance of giving up the “me” for the “we” can be taught and learned. The earlier we start believing in this kind of education and the power of play, the bigger difference we can make.

A School Togetherness Gathering; All that we Share

Another way schools boost fællesskab is through a “togetherness gathering” or fællessamling. These are gatherings of the whole school or parts of the school with the sole purpose of improving feelings of unity and belonging. It has nothing to do with academics.

Some schools hold these gatherings daily, once a week or once a month depending on the school or when it seems necessary. This could be singing together, going on a trip, cooking together, making a mural for the community–or anything that involves everyone being part of a group to practice harmony, collaboration and cohesion. They come together for a common purpose.

These group gatherings help children learn about each other in new ways. You may discover through a common project, for example, that each person has strengths and abilities that kids would never get to see otherwise. Perhaps they have a specific knowledge or trait that is spotlighted in different contexts.

They might have a great sense of humor, an artisanal skill, a culinary talent, or an interesting and helpful perspective. They may be great project managers, coders, or critical thinkers. All of these discoveries can be made through opportunities to be together for different purposes and teachers are often aware of trying to highlight students’ hidden strengths. There may be many things that make us different, but there are also many things that we share.

Kids learn through these experiences that it’s ok to bring diversity to a community. It’s actually a benefit because this is how we bring new ideas, competencies, and perspectives to the group that are invaluable.

As singing is a huge part of Danish culture, another typical “togetherness gathering” is group singing. The singing tradition in Denmark dates back to the traditional feasts of the nobility and aristocracy in the late Middle Ages, it has over time been cultivated and become more popular than ever.

There is a national song book called “Højskolesangbogen” that every school has. Approximately 40,000 of these song books have been sold each year since the 18th edition was published in 2006. That’s a lot of song books for such a small country, and yet, there are never shortages of songs to sing. Danes love to sing all kinds of songs.

For special occasions, they make up funny lyrics to popular tunes where everyone joins in and discovers the words along the way. Singing together is so common in Denmark that most Danes don’t even think about it as special.

Group singing is a very interesting form of creating a sense of belonging; each person contributes to the whole, and each has to work together for it to work. If you sing too loudly you aren’t listening to the others. If you sing too softly, you won’t be heard. It’s only through synergistic teamwork that it functions.

Nick Stewart from Oxford Brookes University has conducted research into choir singers and found that not only does singing in a group make people happier, but it also makes them feel that they are part of a meaningful group. The synchronicity of moving and breathing while singing together creates a strong feeling of belonging.

What about Othering and Bullying?

This isn’t to say that everyone gets along and life is always rosy in Denmark, not at all. One big area where there are cracks in the faellesskab and controversy around othering is with regards to the non-native speaking population, particularly in schools.

A 2006 study conducted in a school in Copenhagen revealed that minority ethnic children (40%) felt that the students of Danish identities (60%) were considered well-behaved nice students while they were considered the troublemakers and bad students. Denmark has tackled this by working to mix school populations for a more even distribution of students’ backgrounds. They have also done some incredibly innovative work looking at othering and bullying in a new way.

Bullying, historically, is described as the more powerful preying on the weaker. It is typically believed that a bully is one or two children who lack empathy and must be dealt with by punishment.

Danes, however, see bullying as a group dynamic. They believe it is a function of the hierarchy of the group, rather than the individual child, and treat it as such.

“We are herd animals.” says Dorte Marie Søndergaard, a Danish bullying expert. “All people have an existential need to be a part of a community. Every child needs to belong, even if the child doesn’t show it. It’s genetic and if this comes under pressure…then a child may think: ‘I don’t know if I am part of the group or not. I have to fight to be part of a group.’ Then a social anxiety can come up for them.”

Social anxiety is not a disease, but a fear that nobody likes you and nobody will choose you. Some children who don’t feel accepted in one group may try to get into another group by finding out what gives them “permission” to get in. This could be having the right toy, clothes, phone, clever comments, or even bullying to fit in.

There are no Bad Children, only Bad Group Dynamics

“There are no bad children, only bad group dynamics,” says Helle Rabøl Hansen, a Danish bullying researcher.

What they find in Denmark’s Free from Bullying program3 is that every class has a hierarchy of popularity. So the popular kids — the ones with the most social capital, so to speak — are looked up to. Then there are those who fall in the middle of popularity and the ones who are lower in the class.

They often see that children who are lower in the hierarchy, in the middle, for example, may be afraid that if they play with one “below” them, the ones above them won’t want to play with them or include them. They may lose social status. So they think “If I play with or talk to William (who has less social capital), then Sebastian (who is more popular) may not want to play or hang out with me.”

Kids at the bottom of the social ladder can eventually become “untouchable” and excluded. In fact, it is common for children to find reasons they don’t like a person merely because they have no social capital. The steeper the popularity gradient, the more issues there are.

Some teachers or parents may think a child may not want to be part of the community or is “just that way,” meaning they are quiet or aloof or anti-social. But Danes believe all children always want to be part of the community, and that it is our responsibility as adults to help them.

Dorte Marie Søndergaard says that “behaviour is almost always driven by the desire to be in the group. What tends to happen is that children feel social anxiety from exclusion. They then have a deep need for security, and this anxiety leads to contempt. It is a defence mechanism.”

That is, they feel the need to disrespect, dishonour, or blame somebody, or look for things others can’t do. They look for ways to “other” them. Generally, they aren’t even aware of it. They may whisper or talk behind others’ backs. There are many ways of expressing this contempt and if this becomes regular and systematic, it is considered bullying.

Neuroimaging brain scanners have shown that the brain regions involved in processing physical pain are the same as those involved in emotional pain and social anguish. There is something particularly devastating about feeling excluded from others because it’s perceived as harmful to our very survival. Having friends is not a luxury for children, it’s fundamental for them to thrive, and for their well-being.

Teachers in Denmark will typically try to develop strategies to help students get into the group and improve faellesskab. Once the student who is out of the group feels more accepted, bad behavior usually stops.

Understanding the Hierarchy of the Group

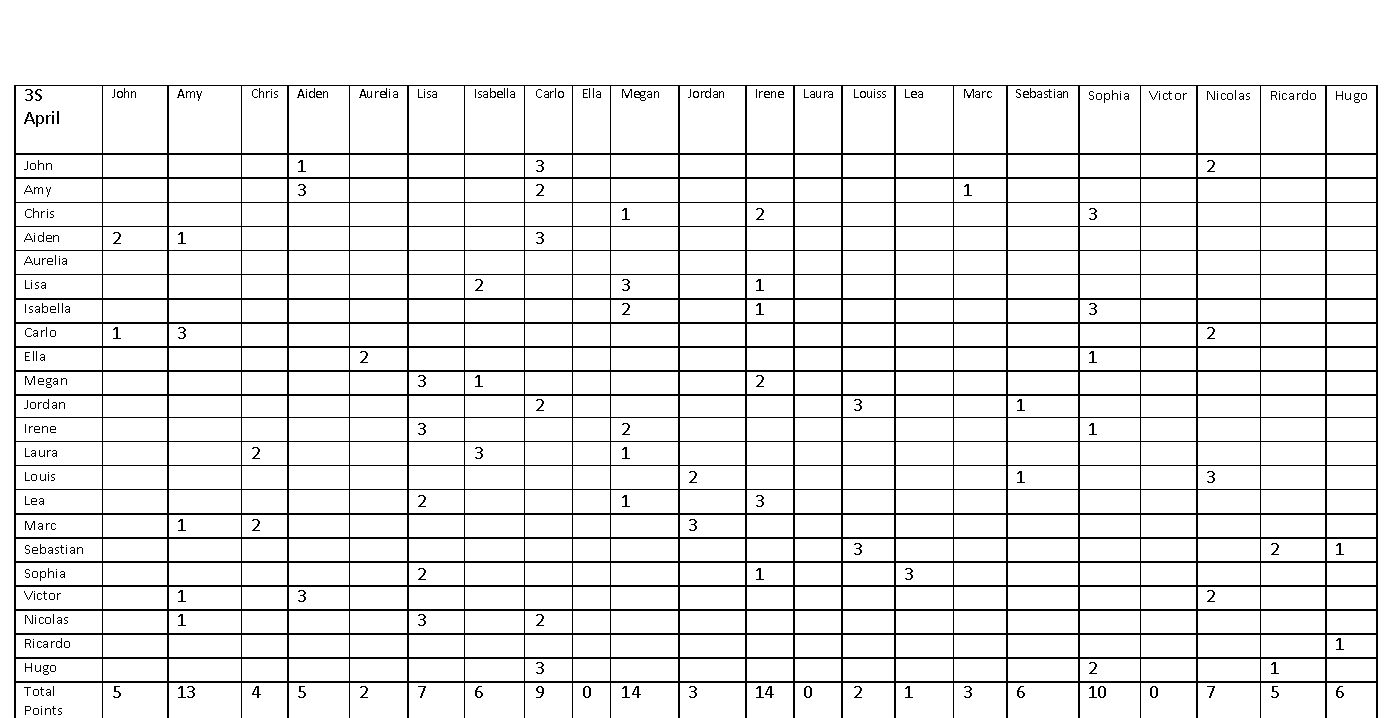

One of the ways teachers stay on top of the social dynamics and hierarchy of the group in classes in Denmark is with a sociogram. A sociogram is a graphic representation that plots the structure of interpersonal relations in a group situation.

Many teachers give regular well-being surveys to keep an eye on how things are going in the class outside of academics. Some call it “taking the temperature” to get a snapshot of the “trivsel”(happiness) in the moment.

These surveys may ask about individual happiness, but also be about the happiness of the group; “Do you think the class feels well together?” Kids are encouraged to think about the group's wellbeing, not just their own.

These questionnaires generally ask students for their happiness number from 1-10 (10 being the best) and then to write down three or four names of students who they most like to spend time with in class in order from 1-3. They might also ask to nominate the top three names of people they think have been a good friend or who they would most like to spend time with that they don’t spend time with now.

The questions can vary greatly depending on the class’s age and situation, but they give great insight to the teacher. They may ask “Is there anyone you feel sorry for in the class?” “Do you hear any mean comments or someone who is being made fun of?” or “Do you think anyone is being left out?"

Once collected, the teacher plots the scores into a sociogram to see the structure of interpersonal relationships. The name on the left is the student who is giving the rating, and the person on top is the name of who they have chosen in order.

Their first choice is worth 3 points, their second choice is 2 points and the third choice is one point. The points get added up at the bottom. This way you can see who is getting the most and least points for being chosen and who isn’t. These sociograms offer a snapshot of the social dynamics and hierarchy of a class in that moment. The class can see who is the most popular and who isn’t getting chosen. The questionnaires are completely confidential between students and teachers.

An Example Outside of Denmark

As part of testing out this approach in a very different culture, a third-grade class in Italy tried implementing the well-being survey, sociogram and Class’ Hour– the results were impressive. One of the questions on the well-being survey asked “Is there anyone you feel sorry for in the class and why?” Every single child in that class wrote they felt sorry for one girl named Maria, and said kids were saying mean things about her.

The teacher was shocked because she had always thought Maria was just quiet and “quirky.” She didn’t realize all the kids felt this way about her or that anyone was being mean to her. She had no idea.

On Maria’s survey, her happiness number was 0 and she complained of having headaches, the number one symptom of being bullied. What was interesting to realize was that the whole class actually did have empathy for Maria, but no one knew what to do about it because it wasn’t being addressed or talked about. They may have been afraid to show empathy for her out of fear of losing their status in the group. They needed help in order to help her.

We take for granted that kids know how to do these things, but they don’t. That is why this view of education as both character development and academics is so interesting and important. Children crave the help to cultivate empathy skills, discuss issues together and experience belonging. These are things that really matter in their worlds.

The teacher ran a Class hour once a week to improve trivsel (wellbeing) for the class. In one of the lessons the students talked about how it felt to be excluded and called names. The children talked openly about this and realized they all agreed about how bad it felt.

The teacher prepared a Trivels lesson plan (wellbeing lesson plan) and read out a mock dilemma of a girl calling into a child help line because someone was being mean to her in class and she didn’t know what to do. The students could choose one of four solutions of how to help the girl.

Each solution was set up in different corners of the classroom. They could go and stand in the corner for the solution they thought was best. There were no right or wrong answers. This was just a way to create physical movement and talk about what to do in this situation.

The solutions were: 1st corner: tell the teacher about it, 2nd corner: tell the person who was calling her names to stop, 3rd corner: go and see if the girl was ok after class, or 4th corner: a combination of the 3 solutions or their own idea.

The teacher talked with the students in each corner about why they chose the solution they did and in the end, the whole class came to the agreement that it was probably best to speak up whenever they hear someone saying mean things. They talked about what it meant to be courageous and agreed that it wasn’t ok to just be a bystander when someone is being called names and that they could help each other in the future.

In only two weeks Maria’s happiness number went up to 9 and kids were writing on their wellbeing surveys that they noticed others being kinder to Maria. She went from sitting on her own at recess to joining the boys playing soccer. She was more active in class and was visibly happier.

The teacher couldn’t believe how little it took to help Maria and how the wellbeing surveys and the Class’s Hour created better values for the whole class. She got so much insight into her students, and her students began to talk about looking forward to the Class Hour all week. Every week someone would bring in a cake, so they always took a little time at the end of the hour to “hygge” or just cozy around playing games, relaxing, and “being” together. It took so little to make a big difference.

These small interventions are a fantastic way to see where bullying or othering may be starting and manage it before it becomes a problem. Often classes have a lot of empathy for students, but they don’t know how to express it because they don’t have the tools or the opportunities to practice being courageous. Unfortunately, it is often the case that no one addresses these issues until they become problems.

“Patterns will always emerge on the sociogram of who isn’t getting requested and who has a lot of friends one week, but none the next.” Says Lene Bech Christoffersen, a teacher who specializes in class unity in Denmark. “These sociograms help identify who is being left out and it usually gives a clear picture of why someone might be disruptive in class as well.”

Belonging is the Key

Kids want to belong and they want to be kind. They really do. But they need help.

If we want to create a better world, it starts with parents, teachers, and policy makers believing that a child’s wellbeing and the wellbeing of the group are inextricably intertwined.

“There are no bad children, only bad group dynamics”. This is an innovative way of seeing the age-old problem of othering and bullying. How can we improve togetherness, rather than placing blame? How can we foster survival of the friendliest rather than survival of the fittest?

What if teachers ran the Class´ hour, organized togetherness gatherings, and elevated something as simple as child’s play, to one of the highest forms of natural learning? What difference could teaching faellesskab make?

In the wake of the pandemic, the world has an opportunity to hit the reset button. We have the possibility to ask ourselves the question: is there a better way?

Looking through the lenses of one of the happiest, most empathic, and trusting countries in the world, is there something we might consider doing differently?

Children who feel well, learn well. This is the motto that yields such positive results in Denmark year after year. And children who feel well, tend to be part of a good fællesskab. Learning to give up the “me” for the “we” helps improve tolerance, cohesion, and empathy, which ultimately improves wellbeing. Isn’t this the real key to unlocking belonging in the future?

Author bios:

Jessica Joelle Alexander is a Bestselling Author, Danish Parenting Expert and Cultural Researcher. Her work has been featured in the NY Times, BBC World News, The Wall Street Journal, Time, Salon, The Atlantic and many more. The Danish Way of Parenting is one of the most sold parenting books of all time and has been published in over 32 countries. She has written 3 books and gives talks on The Danish Way of parenting, education and leadership around the world. She speaks 4 languages and lives in Europe with her Danish husband and two children.

Camilla Semlov Andersson is a Danish Social Worker who has been working with children, families and schools in Denmark since 1999. She is the author and the co-author of several books, which have been well received and she is regularly featured in Danish newspapers, magazines and the radio. Camilla also writes for the National Danish website for Education and gives lectures and presentations based on her many years experience working with families and children.

Artist bio:

Born in Istanbul, based in Berlin, Sera Akyazici is a self-taught photographer capturing fleeting candid moments of intimate social interactions.

@seraares / touristofficial.com

Art description:

I have been always naturally inclined to capture photos of communities that I belong to: predominantly my family and friends, imbued with nature elements. Holding a strong relationship with the subject being photographed not only expands my artistic freedom but also strengthens my relationships with my community through accumulating pictorial memories. This inclination towards having a personal relationship with the subject(s) captured, is in line with Jessica Joelle Alexander’s words on unlocking the feelings of belonging through communal “we” instead of singular “I”. This we/I duality can be found in two of my photographs quite vividly: one exhibiting a single hand touching nature by intimating nature/human duality, while the second photograph is breaking down this duality through double-exposure technique. Belonging, to me, is when dualities can co-exist together in a peaceful manner.

- 1 Othering can be described as the intentional exclusion of a person, race, culture, or practice into a distinct “other”. The process of othering (from the dominant group) often involves the implication (and reification) that there is some level of inferiority of the other. See intro to this journal for an expanded definition of othering and belonging.

- 2 An exploration of these issues is of essence and would require an essay of its own. Where pertinent, it has been brought into this paper but delving deep is beyond the scope of this publication.

- 3 For more information visit: https://redbarnet.dk/media/1645/free-of-bullying-information-leaflet.pdf.