KEY FINDING TWO

Address, don’t ignore, the fears, anxieties, and uncomfortable beliefs of key constituencies, particularly where anti-Black racism and immigrant resentment are present

Over the past few years, much attention has been given to privilege—the phrase “check your privilege” is well-known to most Americans by now. While this has certainly helped make more people, particularly white Americans, aware of racial and economic inequality, it has also centered white privilege in the larger discourse around racial justice at the expense of scrutiny toward other significant barriers to belonging. Structural racism, as discussed in the previous section, is one such under-scrutinized barrier. But another, perhaps less comfortable one, is the presence of othering, anxiety, perceived competition, and, in particular, anti-Black racist attitudes within many of the communities in which we work.

Our recent research in Riverside, San Bernardino, and Orange counties in Southern California, for example, reveals that substantial minorities of Latinx and Asian American respondents agree with statements extolling individualist, anti-immigrant “bootstrap” narratives, and decline to sympathize with challenges faced by many immigrants. The surveys also show that older members of these communities are just as likely as whites to reject the idea that Black Americans still suffer from the continuing impacts of enslavement, discrimination, and systemic oppression.8

“White supremacy is ‘in the air that we breathe’ and propagated by the systems which organize our lives.”

Similarly, a significant share of older African Americans believe the idea that they are in competition with Latinxs for good jobs, such that a benefit to one group comes at a cost to the other. Nearly half of those fifty and older hold this idea, compared to just 28 percent of African Americans under age fifty. While we uncovered several promising signs for solidarity across Black, Latinx, and Asian American communities in Southern California as well,9 results like these expose vulnerabilities to politics of division that cannot be ignored in political advocacy contexts and movement building more generally.

To be clear, this is not an indictment of communities of color. Like most widely held beliefs and attitudes, white supremacy—particularly when manifested as anti-Black or anti-immigrant biases—is “in the air that we breathe” and propagated by the systems which organize our lives. Yet we will not fully tackle othering on a wide scale unless we also address its manifestation within the communities in which we work, and this means acknowledging uncomfortable beliefs within our narrative frameworks.

Too often we jump quickly to stories that depict a harmonious progressive community that crosses race, gender, class, ability, and other lines without acknowledging persistent anti-Black, anti-immigrant, sexist, ableist, or related othering sentiments. In doing so, we can inadvertently ignore profound pain and suffering, and thereby “break” with our brothers and sisters who are, for example, Black or immigrant. This type of breaking stands in the way of the coalition building and trust-based partnerships that are necessary for successful movement work. A seemingly multiracial effort to address an issue like structural inequality is at risk of failing if these underlying tensions are not addressed.

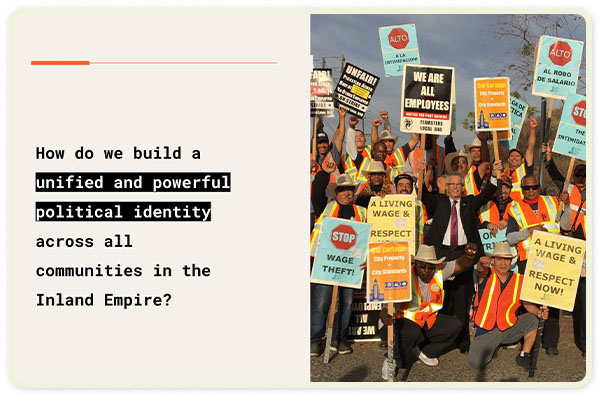

Of course, merely being aware of threats of breakage does not necessarily translate to utility within a strategic narrative. Our ongoing work in Southern California’s Inland Empire (Riverside and San Bernardino counties) can offer a blueprint for how a strategic narrative for belonging that acknowledges breaking might look.

The narrative we developed with movement partner Inland Empowerment involved starting with a place of solidarity by centering a shared place-based identification (“in x community, we know that…”). The narrative then offers a structural analysis of the problem by highlighting the unjust extraction of wealth by corporations in the region, and then goes on to call out narratives that rely on racial scapegoating to explain unequal economic outcomes (“Some people try to explain why we’re struggling by pointing to people of other races—saying immigrants take our jobs, or Black people don’t work hard enough. But that’s not right and we know it.”). The roadmap linked at right offers a more in-depth look at this narrative and how it addresses breaking between groups while working to foster civic engagement and hope for a better and brighter future.

Case Study

PICO California puts bridging into action

Our partnership with PICO California is perhaps the ultimate example of an organization openly engaging with uncomfortable attitudes between and among identity groups—and, by doing so, helping build stronger bridges between groups and individuals fighting for racial justice. To strengthen its political advocacy efforts in 2019, PICO California launched over one hundred bridging and belonging circles, engaging Californians from across faith, race, economic, and social backgrounds.

The circles initially met with resistance as participants felt distrust toward one another, particularly when those with more marginalized identities found themselves in an intimate circle with people from more privileged identities. As the months went on and the relationships within the circles deepened, participants began to express the deeply spiritual experience they were sharing, ultimately serving to build real trust between disparate groups and strengthen the larger movement working toward a shared progressive vision.

According to PICO leadership, the workshops around bridging and belonging have helped them develop a powerful narrative that grounds major new initiatives, including an effort to advance police accountability in communities of color in fourteen California cities. The concept of belonging allowed community organizers and participants to connect themselves to a reference point that can guide the way toward collective justice and liberation in relation to multiple issue areas, whether or not they arrived already familiar with a particular issue or even an analysis around race and equity. PICO California co-director Rev. Ben McBride reflected that “this [belonging] frame led us to create new kinds of practices and design spaces that were about building shared humanity, bridging across differences, and then creating new structures.”

“Bridging involves explicitly affirming the unique and distinct identities that each person brings”

PICO’s adoption of bridging is significant because it is a departure from—and calls for critical reflection upon—certain long-standing approaches to organizing. First, to center bridging implies choosing to decline emphasis on villains, common enemies, or simply what “we” are against—an approach that is reliant on othering and breaking. Also, bridging involves explicitly affirming the unique and distinct identities that each person brings, whereas many organizing efforts prefer to ignore difference among constituents, under the misguided idea that difference is bad for unity. This problem exists even in some current narrative strategies. Even if the goal is to be inclusive and progressive, a narrative that stops at shallow “shout outs” to each identity group will fail to capture and “call in” the diversity of Black and other communities of color into its collective “we.”

PICO is consciously seeking a new way of organizing in which intersectional experiences of pain, anxiety, and fears are acknowledged, addressed, and used to fortify intergroup relationships for stronger coalitions and longer-term community wins.

Photographs courtesy of PICO California.