From Estrangement to Engagement: Bridging to the Ballot Box

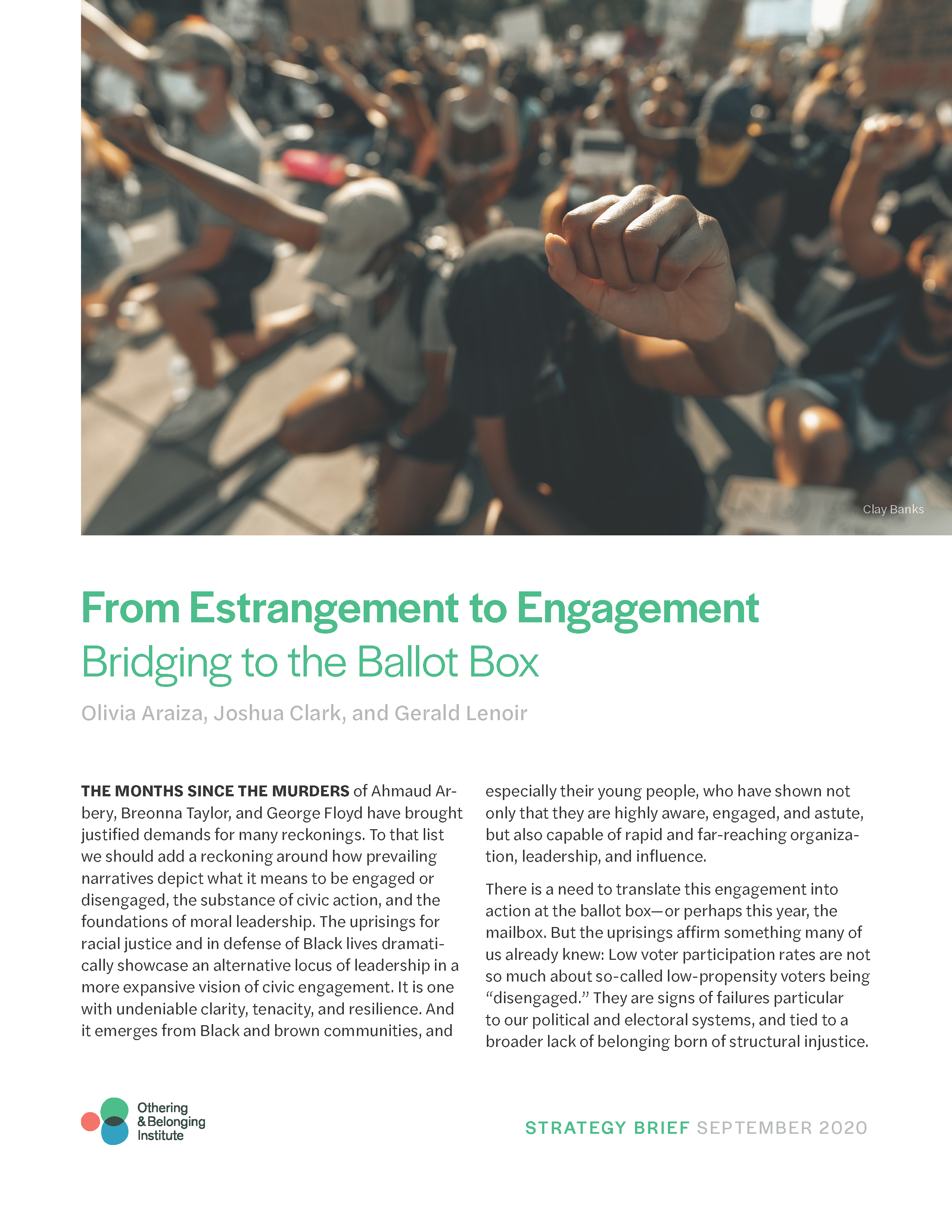

THE MONTHS SINCE THE MURDERS of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd have brought justified demands for many reckonings. To that list we should add a reckoning around how prevailing narratives depict what it means to be engaged or disengaged, the substance of civic action, and the foundations of moral leadership. The uprisings for racial justice and in defense of Black lives dramatically showcase an alternative locus of leadership in a more expansive vision of civic engagement. It is one with undeniable clarity, tenacity, and resilience. And it emerges from Black and brown communities, and especially their young people, who have shown not only that they are highly aware, engaged, and astute, but also capable of rapid and far-reaching organization, leadership, and influence.

There is a need to translate this engagement into action at the ballot box—or perhaps this year, the mailbox. But the uprisings affirm something many of us already knew: Low voter participation rates are not so much about so-called low-propensity voters being “disengaged.” They are signs of failures particular to our political and electoral systems, and tied to a broader lack of belonging born of structural injustice.

This brief summarizes key insights and applications from research on strategy for expanding the electorate and fostering bridging across lines of difference for greater civic belonging. It is based on (1) the authors’ original research, both qualitative and quantitative, through the Othering & Belonging Institute’s Blueprint for Belonging and Civic Engagement Narrative Change projects,1 (2) secondary research by other scholars and applied researchers, and (3) lessons learned from leading voices in Black- and Latinx-led organizing efforts, through the authors’ ongoing collaborations and strategy dialogues with civic engagement and power-building organizations nationwide.

The synthesis of research and experience offered here is geared toward application in the field in 2020. Our focus is on communities that have been suppressed and underrepresented in electoral participation in the United States, especially Black, Latinx, and other people of color, and young people. No community, much less a whole racial or ethnic group, is monolithic; the lessons we offer here are presented to the scale at which our findings are robust and resonant across research efforts.2 These lessons are not comprehensive, but they are empirically well-grounded and timely. The research of the Civic Engagement Narrative Change and Blueprint for Belonging projects in the areas covered here remains ongoing.

Understanding Barriers to Voter Participation

It is widely known that in the United States, rates of voter participation are uneven across voter groups situated differently in relation to hierarchies of race/ ethnicity, educational attainment, income, and age. But the point is often not made in that way. Conventional media and popular discourse tends to assume non-participation arises from simple cynicism, or lack of interest, awareness, “initiative,” or regard for the importance of elections. We must prevent these assumptions from bleeding into our work to expand civic participation and belonging. We should instead root ourselves in these key lessons on inconsistent voters’ perceptions:

- Knowledge of undemocratic structures and political influence. The pervasive influence of money in politics is one of the factors that most discourages underrepresented communities from believing that their vote matters. The Electoral College system for selecting presidents is also a common reference point in expressions of distrust in the integrity of elections. Outreach efforts should articulate to skeptical voters a vision for how engagement and the building of independent political power can address the outsize influence of money in politics and anti-democratic structures.

- Lack of identification with candidates. Where voter groups are underrepresented at the polls, one of the key reasons is that they feel unrepresented by the candidates and standard bearers who have been elevated by political parties. Even those voters who say that they don’t follow politics are keenly aware of who is at the top of the ticket in their state, and for the presidency. They are also aware of the demographic composition of their communities, the changing demographics of the country, and the mismatch between lives lived in their shoes versus those of candidates for top elected offices. Their resulting skepticism about these candidates should be acknowledged as a starting point for engagement.

- Acute poisoned electoral experiences. In some cases, underrepresented voters have made the leap of faith into electoral action and hopefulness, only to be denied the rightful impact of their engagement—whether individual or collective. We must always be careful about labeling votes or electoral losses as “stolen.” Representing “stolen elections” as though they were a common occurrence can further discourage disillusioned voters from future participation. But there are cases—such as the 2018 elections in Georgia that were riddled with multiple discriminatory administrative anomalies, or instances of emergency managers being appointed to displace duly elected local officials—in which voters’ only logical reaction would be to become discouraged. These experiences must be acknowledged in the course of re-engagement.

“Yo hace cuatro años voté por mail con mi hijo y después nos vino una carta a los dos, diciéndonos en la casa que nuestro voto no había sido contado porque no habíamos firmado. Y mi hijo y yo, los dos estamos muy seguros de que firmamos el voto, porque para nosotros era muy importante y lo tomamos como una cosa muy seria. Y los dos votos nuestros fueron botados… Entonces, después de esa experiencia… no sé. Es que no sé todavía ni qué voy a hacer.”

Four years ago I voted by mail with my son, and later a card came to each of us at our home, telling us that our vote had not been counted because we hadn’t signed. And my son and I, both of us are very certain that we signed the vote, because for us, it was very important and we took it as a very serious thing. And our two votes were thrown out… So, after that experience… I don’t know. I still don’t even know what I’m going to do.

-CUBAN AMERICAN WOMAN South Florida, 2020

- Internalized othering. With great frequency, our research has found a tendency among voters—especially young voters—to say that they don’t know enough, or don’t feel enough like a “political type” of person, to cast a vote. This type of self-disqualification seems to arise at the intersection of (1) messages that other and condescend based on race, age, gender, language proficiency, etc., undermining voters’ self-confidence; and (2) the erroneous idea that those who consistently vote are especially knowledgeable or responsible in their electoral choices. Outreach efforts should dispel the latter myth, while concertedly building the confidence of those who have internalized the pernicious idea that they have less claim to civic participation and belonging.

- Proud refusal to be used or fooled. For many who feel that their communities have been tricked, sold out, and taken for granted by dishonest politicians and institutions, withholding the vote is an act of proud defiance. It is not inaction, but the only option for many voters who are ignored and disparaged to not feel that they are being used. Acknowledging that voters exercise agency when they choose not to vote is a good starting point in trying to turn that agency toward participation.

“Like right now, I could send a vote, [and] I don't know how it's getting counted. I don't know exactly how it's making its way. And then how a decision is actually based on those votes… [Y]ou know stuff that's done on computers. All that could be easily manipulated. And a lot of people are gullible to believe whatever they're just told.”

-YOUNG LATINO MAN San Bernardino, CA, 2019

Motivating Voter Participation

GOOD PRACTICES

- Do speak to aspirational visions of community and personal empowerment, while acknowledgement and affirming that communities that have been excluded—our communities—are resilient and strong.

- Do trust that Black political leadership and cultural expression are effective for engagement with young people across lines of race.

- Do understand and take into account cultural differences concerning where, when, and how it is appropriate to “get into politics.” This may include adapting the way engagement is discussed to be inclusive of people with different statuses and ways they are impacted by disenfranchisement. More broadly, it is about being conscious of norms around when it is appropriate to make a call to action, and the steps of listening, trust, and identity building needed to get there in a particular cultural context.

“Apenas empecé, hace unos cinco años, empecé a votar… Nunca me había registrado. Nunca estaba interesada – nada… [Entonces] me dice mi marido, ‘¿Sabes qué? Debes de ayudar. A votar. Tú, que eres ciudadana, debes de ayudar ya que eres ciudadana de aquí.’ ”

I just started, five years ago, I just started voting… I had never [even] registered. I never used to be interested – nothing… [Then] my husband says to me, ‘You know what? You should help out. Vote. You, who are a citizen, should help out, now that you’re a citizen here.’

-LATINA WOMAN Moreno Valley, CA, 2019

- Do activate voters around voting for those in their community who can’t. Voters in communities with many members who are disenfranchised, either due to being non-citizens or for past felony convictions, often find inspiration in being able to stand up for them by “being their vote.” This is a message that resonates.

- Do activate voters around voting as a way to show their community’s size and clout. Though many voters may not spontaneously think of voting as a way to increase the public and political visibility of their communities—or, to show that they are “too many to ignore”—our research finds that this message also resonates. This is another way of making the case that voting is not something to do for politicians, but something to do for your community.

- Do foreground local races and ballot initiatives as reasons to vote. Sometimes there is no way around voters’ reasoned disinterest in the candidates at the top of the ticket. Focusing on “down-ballot” races often connects voting to issues directly linked to voters’ everyday experiences, and likely candidates who are more in touch with those local experiences.

“I don't know if I'm necessarily excited about it, but I do feel like I want to choose a candidate who's going to be an advocate for me or my community, as well as their cabinet. And even just at a local level—people who look like me, who are there to advocate for me, and enforce new policy that protects me, and things like that.”

-BLACK WOMAN Chicago, IL, 2020

- Do stay vigilant and develop plans for countering misinformation and dissuasion efforts on social media or unreliable “news” outlets. These are likely to include intentionally inaccurate information about how to vote, and about candidates and parties, as well as narratives meant to stoke cynicism as a strategy to decrease turnout.

- Do point to recent policy decisions about Covid-19 response as evidence that the decisions of elected officials have real impacts on our everyday lives. The crises brought by Covid-19 and the patchwork of policy responses to it have made many voters rethink previous beliefs that things will be the same for them no matter who wins elections. The pandemic has shined a light on the importance of state and local elected officials in particular.

“[Ahora] viendo, lamentablemente, esta pandemia que estamos pasando, cómo las personas en el poder están tomando decisiones que afectan el diario vivir. No tan solo de nosotros, de las personas que nos rodean, las comunidades. Porque en estos tiempos, pues ahora es que más necesitamos de los líderes de nuestro país… Y al final del día, uno tiene que velar de quién uno pone en poder, para que tome las mejores decisiones.”

[Now] seeing, regrettably, this pandemic that we’re living, how the people in power are making decisions that affect everyday life. Not just our own, [but also] of the people that are around us, the communities. Because in these times, now more than ever we need [things] from the leaders of our country… And at the end of the day, one has to keep up with who one puts in power, so that they make the best decisions.

-PUERTO RICAN MAN Miami, FL, 2020

- Do link voting today to staying engaged tomorrow, and holding electeds accountable. Voters who have felt burned in the past need to know that those with whom they make common cause are not just “in it” for their vote. They need to know that the civic and community organizations that implore them to vote will carry forward commitments to real change, recognizing that we cannot count on candidates to do so themselves once in office. Calls to vote should always be connected to plans for staying mobilized and holding electeds accountable. The message and commitment is: We will not be demobilized again.

BAD PRACTICES

- Don’t tell someone who is skeptical about voting that they “have to” vote, or to “just vote.”

- Don’t attempt to shame people into voting. There is a thin line between commonly employed “social pressure” tactics and shaming. Moralizing or condescending language, and talk of “responsibility” around voting, tend to be alienating, because they read as dismissive of the experiences of duly skeptical prospective voters.

- Don’t expect that getting people angry— even if it is righteous anger—about the status quo will be enough to motivate them to vote. Often emphasizing reasons to be angry—however justified—plays into an underlying cynicism or fatalism about power imbalances and corruption in electoral politics among disillusioned voters. It can inadvertently tell them that they are correct to feel powerless in the face of a deeply unjust system, or the dirty business of politics.

- Don’t assume Barack Obama’s 2008 election is considered a success story of what can happen if more young, Black, and Latinx people vote. For many who are disaffected from electoral politics—including those engaged in activism to end police violence and attacks against immigrant communities—the Obama presidency is a signal example of why it doesn’t matter who shows up for, or who wins, elections.

“My first experience voting was for Barack Obama. And I voted because I thought he could make a change, as well as him being one of us. But when he got in office... [pause] They say the president run the country, but he don't. He's a puppet too.”

YOUNG BLACK MAN Chicago, IL, 2018

- Don’t activate voters by telling them that they owe a debt to past generations who fought for the right to vote. Our research shows that recalling past generations’ struggles and sacrifices resonates with many voters, but: Those voters with whom it resonates do not need to be reminded. For those who are not moved by these appeals, reminders can sound tone deaf and dismissive of their contemporary struggles and legitimate criticisms of the system. There are plenty of examples of struggle, sacrifice, and resilience in today’s generation of young people upon which to draw when making calls for further civic action.

Reach of Narratives of Division/Othering

Politics in the United States is replete with language and practices of division, exclusion, and othering. As a strategy for diminishing and distorting the electorate, this is not new, though the tactics of politics of division are always evolving. One of the under-studied facets of politics of division—which most concertedly target whites and aim to stoke white resentment—is their prevalence, character, and hold within and between communities of color. Our research has centered these issues, and here we note some of the outstanding findings from our work.

- Black-brown tensions tend to live in narrative. Our research has found again and again that negative feelings between Black and brown communities are most often rooted not in personal interactions and experiences, but in hearsay, assumptions, and misunderstandings. Sometimes tensions arise from isolated incidents from which those involved build generalizations about the other group. But perhaps due to pervasive segregation in the U.S., much more often such tensions live at the narrative or discursive level.

- Immigrant communities are also vulnerable to anti-immigrant narratives. There is a common anti-immigrant narrative that immigrants come in two “types”—the hard-working, consenting, “good” immigrants, and the dependent, dangerous, “bad” immigrants. Our research with Latinx immigrant communities finds that this narrative is also present within these immigrant communities themselves. Such internalization of anti-immigrant sentiment is no doubt largely a defense mechanism. The unfair demand upon immigrants to constantly prove that they are not misusing (or even using) public services pushes them to contrast themselves with those who do, often disparagingly. There are examples in movement spaces of effectively countering this good immigrant-bad immigrant framing; more such work is needed.

- “Good immigrant”/“bad immigrant” narratives often also engender anti-Black racist narratives. The same dynamic described above, which sometimes drives Latinx immigrants to defend their own deservingness by repeating tropes about “bad” immigrants, also drives some to invoke racist tropes about Black Americans. Here the demand to prove themselves as hardworking and law abiding can lead immigrants to unfairly mischaracterize Black Americans in ways that feed tensions between communities, and further anti-Black racism.

- Tensions across Latinx immigrant communities often arise around differences in reception and treatment in the U.S. based on national origin. Policies governing who may enter the United States—and what rights they are likely to enjoy upon entry—differ greatly by country of origin. The perception that some national-origin groups are favored, or “have everything given to them,” by U.S. policy is a source of tension. Differences of status are particularly likely to cause fissures where they lead to claims and counterclaims about which forms of deprivation or injustice make a migrant “deserving” of entry and full rights and protections in the United States. Some U.S. political actors stoke such fissures by “picking favorites” and courting particular national-origin groups, in line with ideological and geopolitical interests.

Bridging to Civic Belonging

- Resource competition between Black and Latinx communities. Our surveys in California, Florida, and Nevada all show that the perception among Black and Latinx individuals that they are competing for the same resources is far less pervasive on the ground than is often depicted. Far more members of these communities believe that it is whites with whom they are competing for good jobs and housing.

- Black Americans recognize the impacts of structural barriers and racism on immigrants’ opportunities in the United States. Our surveys show that Black Americans—more than any other race/ethnicity group—reject statements saying that immigrants’ success depends only on trying harder, working their way up, and pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. Their responses reflect their consciousness of the continuing impact of structural and historical antecedents to current inequality.

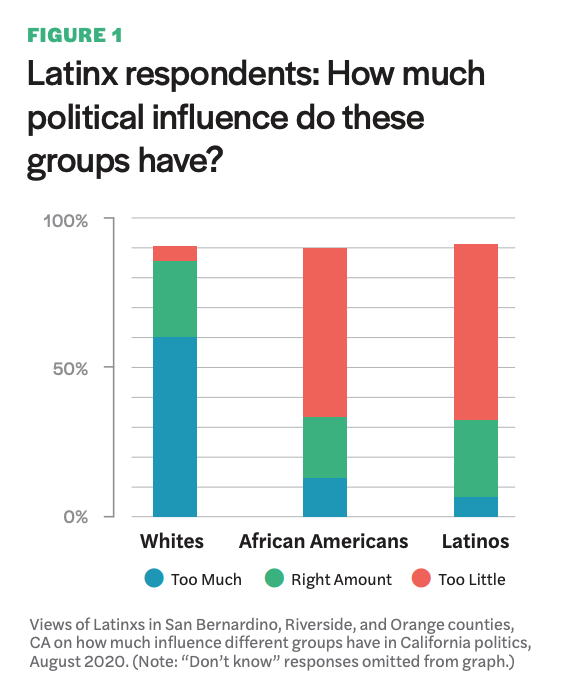

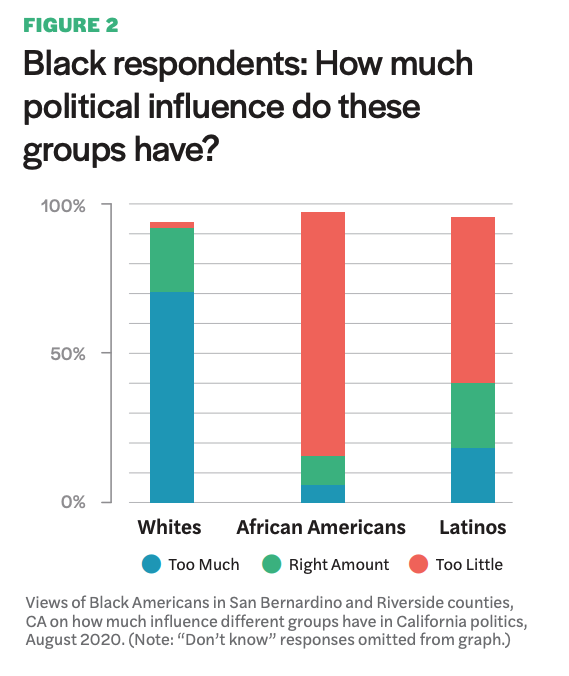

- Mutual recognition of political underrepresentation. Across Black, Latinx, and Asian American and Pacific Islander communities, there is shared recognition that one another’s race/ethnicity groups have “too little influence” in politics. Consistently 40-50 percent of each of these groups say that the others deserve more political influence—a solid foundation of political solidarity that should be brought forward in bridging narratives and strategies (see Figures 1 and 2).

- Most Black and Latinx community members don’t know of examples of their communities trying to work together on a common problem. Overwhelmingly our research with Black and Latinx communities found a dearth of experiences—good or bad—with cross-group bridging. Research participants could not think of times when they, or others in their community, had intentionally crossed lines of difference to address a shared problem. Again, this reflects deep patterns of segregation. But it also underscores an opportunity. It is not that we have tried and failed. Instead, it is that attempts at experimenting with bridging either have not been explicitly articulated as cross-group collaborations, addressing the issue of difference; or simply have not existed. The gap in personal experiences is being filled by assumption and speculation about how and whether different groups can work together.

INTERVIEW QUESTION

Some say that addressing some of these big issues really takes people reaching out beyond their own community and working together across lines of difference. Have you heard stories of that kind of thing before?

Not on a larger scale. Outside of co-workers and outside of friends, I haven't seen it from neighbors or anyone else that live nearby.

-YOUNG LATINA WOMAN Montclair, CA, 2019

De primera mano, no. Ni de segunda mano nunca he escuchado, no.

Firsthand, no. Not secondhand either, I’ve never heard [of that], no.

-LATINO MAN Moreno Valley, CA, 2019

Not really. No, not really. Not out here. I feel like everything is in pockets out here.

-YOUNG BLACK MAN Corona, CA, 2019

I've only seen it in small pockets, and it's usually related to business, or some type of job or industry… But unfortunately, what happens most of the time is, as soon as a person's needs are met, they're not encouraged or taught to look beyond.

-LATINO MAN San Bernardino, CA, 2019

TOOLKIT: Our Digital Products Election 2020

Can You See It? We know it better than anyone: Americans of all backgrounds are doing extraordinary things with whatever they have. But can you imagine what our neighborhoods could look like with all the resources to thrive? That’s the question posed in “Can You See It?,” a 90 second GOTV short (also in a 30 second version or in Spanish) produced in partnership with California Calls. The short features a young Latina woman biking through her neighborhood imagining what could be if there were money to fund community resources—which would be possible if corporations paid their fair share.

Are Our Elders Expendable? This is the first episode in a larger series “(ILL)Logic: Rethinking the Covid-19 Story,” which seeks to expose how dominant political narratives around this crisis moment are flawed or false, and are being strategically wielded by political actors to avoid culpability for ongoing suffering. This first 10-minute episode, which can also be viewed in an abridged 2 minute version, explores the narrative that our elders should be expendable for the economy, as exemplified by comments from political leaders suggesting that the economy has more value than the safety of vulnerable people.

We The People This animated short exposes how the unmitigated power of US corporations is bolstered by divide and conquer tactics wielded to distract from the harm they do to society and the environment—and generate enormous profits for the wealthy few. The video sheds light on how narratives of scarcity (“There aren’t enough jobs for everyone,” “We can’t afford to pay a living wage,” etc.) work to shield the public from seeing just how wide these corporate profit margins really are. It is government’s responsibility to ensure that corporations serve us, not exploit us.

- 1Details on our original research are included in this brief’s Appendix, together with a list of partner organizations with whom we have collaborated in its design and development.

- 2Where quotes from research participants are featured in this brief, those speakers are identified by their stated ethno-racial and gender identities. Where the individuals are under 35 years old, we further designate them as “young.”