The population of Riverside and San Bernardino counties has increased dramatically in recent decades, growing from just over 1.5 million in 1980 to 4.6 million in 2018.23 With this rapid growth has come a transformation in the makeup of the region’s communities. Though never nearly racially homogeneous, the two-county Inland Empire was majority white (non-Hispanic) into the 1990s, with whites making up over 60 percent of the population in the 1990 U.S. Census.24 But between 1990 and 2010, Latinxs accounted for around 80 percent of the region’s burgeoning population growth.25 The two counties also gained a combined 250,000 new Black residents between 1980 and 2010, and 230,000 Asians.26 By 2017, just over half of Inland Empire residents were Latinxs; two in three were people of color; and one in five was born outside the country.27

Much of the migration to the Inland Empire since the 1980s has been fueled by demand for affordable housing. The inland region has long offered Los Angeles metro residents the promise of more space at relatively lower prices. Deirdre Pfeiffer has documented how this promise—together with those of greater safety, peace, and quiet—rippled through LA’s Black communities in the 1980s and ’90s, through both fliers and word of mouth.28 As home prices in Los Angeles continued to soar, housing production in the Inland Empire boomed, and demand for construction workers drew additional new residents, many of them of Mexican and Central American origin.29

Our interview and focus-group participants echoed the idea that the Inland Empire is a magnet for those seeking “more for less.” But they also challenged the region’s reputation as affordable. In focus groups, the cost of living and housing affordability were among residents’ first and most commonly referenced concerns. The predominantly low- to middle-income Latinx and Black participants shared stories of multiple jobs, frequent moves, and as-yet unrealized dreams of homeownership.

Currently, I work three jobs and—I don’t have any children—but I work three jobs to support the household I’m currently living in with my boyfriend. He works three jobs as well. That goes to the cost of living here in California.

[Other participants verbalize agreement.]

We live in one of the most affordable areas in the city [that] we live in. It’s cheap—very cheap, I would say, compared to surrounding cities. And we still both work those multiple jobs.—Participant 6, young women of color focus group

Fifteen years ago, these individuals would have fit the profile of new homebuyers in the Inland Empire—but as targets of predatory lending. In the decade of the 2000s, mortgage brokers in the region aggressively marketed subprime loans to first-time Black and Latinx homebuyers, who were subsequently hit the hardest by the 2007-2009 foreclosure crisis. For these communities, the effects of the crisis endure in the forms of erased wealth, income stagnation, and poverty that leave them unable to take advantage of sustained dips in home prices and interest rates today.30

Indeed, a significant share of Inland Empire residents continued to live at the edges of security when COVID-19 hit, bringing another economic crisis. In our survey of the region, 28 percent of respondents said that, since the arrival of the coronavirus, they had begun to worry about whether they would be able to pay the next month’s rent or mortgage. This added to the 13 percent that already worried about housing security prior to the coronavirus, bringing the total to more than two in five residents who are housing insecure. As Figure 5 shows, the jump in housing insecurity since COVID-19 has been felt disproportionately by Black and Latinx residents. Even more dramatically, the onset of the coronavirus increased the share of renters in the Inland Empire who feel housing insecure from 20 to 60 percent.

Figure 5:

Housing insecurity in the Inland Empire, before and since COVID-19.

Responses to the Summer 2020 B4B Survey Question: “Thinking about the last 12 months, have you ever been worried that you won’t be able to make the next month’s rent or mortgage payment?”

Belonging in the Inland Empire Today

Just as the foreclosure crisis and ongoing housing insecurity are felt unevenly across the inland region, so too are residents’ subjective experiences of belonging. This sense of belonging is important as both a good in itself, and a gateway to greater agency and well-being among individuals and communities. Decades of research in psychology attest that the need to belong is a fundamental motivator of human activity across the life course. The presence or absence of the social attachments that create a sense of belonging has a strong influence on individuals’ mental and physical health and security.31 When people feel that they belong, not only do they have a sense of ease, comfort, and acceptance; they also enjoy the capacity to make claims on shared resources; shape collective values and culture; and change structures that impact them.32 The lack of belonging, then, is a serious and far-reaching form of deprivation.33

The Blueprint for Belonging survey asked respondents to say how often they feel a sense of belonging, understood as feeling comfortable, safe, and with a say in the important things happening around them, in a series of different settings.34 Although over 90 percent of Black, Latinx, and white residents experience belonging “most” or “all” of the time when at home, substantial shares (25-40 percent) usually do not feel belonging in their neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, and other public spaces. Notably, schools are the place where the largest share of respondents do not experience belonging most of the time—a troubling finding given the ideal of schools as sites for the building of community bonds.35

The shares saying they usually don’t experience belonging in the Inland Empire were relatively steady across race/ethnicity groups, with some exceptions. Overall, 25 percent of residents said that most of the time they do not feel belonging in their own neighborhoods, and 37 percent usually do not feel belonging on the street or in public places. But these figures were higher for Latinx respondents, especially women. For example, 46.5 percent of Latina women usually do not feel belonging on the street or in public places. When these women were asked the follow-up question of what things made them feel that they didn’t belong, almost half said their race, a third said their culture or background, and 27 percent said their gender.36

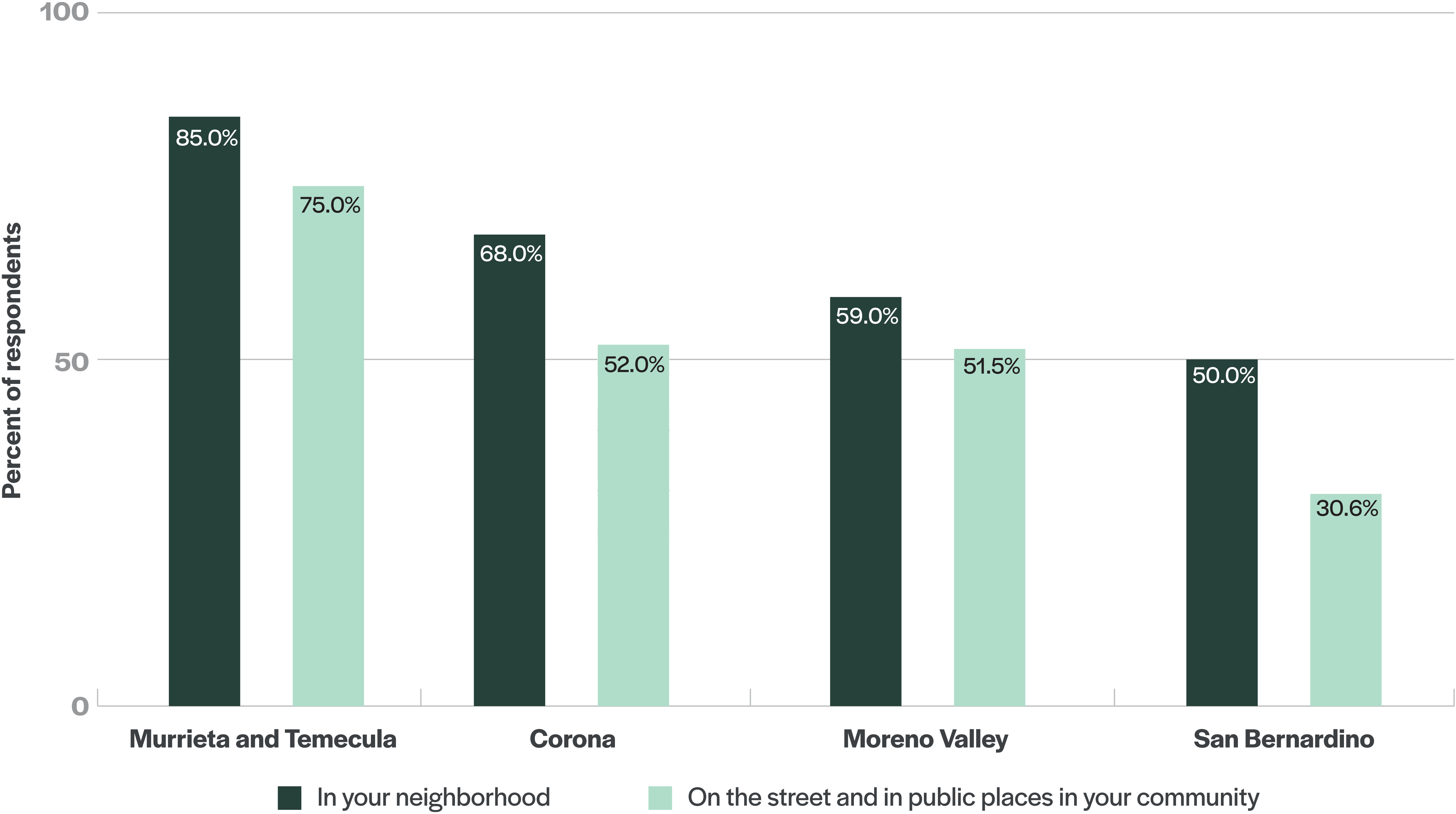

More striking disparities in experiences of belonging exist across residents of different Inland Empire cities. On the southwestern edge of the region, 85 percent of residents of Murrieta and Temecula report feeling belonging most or all of the time in their neighborhoods, and 75 percent say the same for public places more generally. These cities, Juan de Lara writes, “have openly marketed themselves as upscale white-collar communities,”37 and according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income for the two is around $92,000. Their residents’ experiences are in sharp contrast to those of more working-class cities in the Inland Empire’s population and warehousing-industry center. There, at the other extreme, is the city of San Bernardino, where only half of residents usually feel belonging in their neighborhoods, and just 30 percent feel belonging on the street or other public places in their communities (see Figure 6). The median household income in San Bernardino is under $46,000—half that of Temecula and Murrieta.38 As was true for the region in general, the most common characteristic to which residents of San Bernardino attributed their feeling of not belonging was their race.39

Figure 6:

Varied experiences of belonging across cities in the Inland Empire.

Share of Inland Empire residents who feel a sense of belonging “all” or “most” of the time, by city of residence.

What “Community” Means to Inland Residents

The above sections described communities in the Inland Empire in terms of growth and change in the population’s ethno-racial composition, and experiences of belonging and not belonging. But what does the nebulous notion of “community” mean to residents themselves? How do they conceive of “their community,” and the boundaries demarcating where it begins and ends?

We explored these questions through open-ended prompts in our focus groups and interviews with inland residents. Overwhelmingly, the first associations that came to their minds were place-based boundaries—community as the people living in a neighborhood, school district, or city. In connection to this, we heard from many residents that one’s specific city is a meaningful and distinguishing marker of identity and community within the larger region, even in the dense metropolitan core of the Inland Empire where outsiders might pass from one city to another without even realizing it.

After the geographic, the next most common coordinates of “community” cited by Inland Empire residents were those of race/ethnicity. “My community” meant, for example, the Black community, Mexican-American community, or Spanish-speaking immigrant community. However, as residents shared stories and discussed how “community” feels, it became clear that the ethno-racial definition was often more a shorthand than a fixed boundary marker.

Si estoy en mi casa, en mi barrio… yo no me voy a poder poner hablar con una persona que la vea afuera… No hay la facilidad, no es común, en la comunidad que yo vivo, de nomas acercármele a una persona y hablarle. No sé de qué manera lo van a tomar. En otros lugares, como la iglesia, yo sé que me puedo acercar tranquilamente a hablar con una persona, tener una conversación de cualquier cosa, sin ningún problema. Sin pensar, ellos están bien – la reacción de ellos. Yo creo que es el sentido de estar cerca con una persona de una manera más íntima… que crea ese sentimiento de ser parte de una comunidad.

If I’m at home, in my neighborhood… I’m not able to go up and talk with someone who I see outside… There isn’t the ease, it isn’t common, in the community where I live, to just approach a person and talk to them. I don’t know how they’re going to take it. In other places, like [my] church, I know that I can calmly approach to talk to a person, have a conversation about anything, with no problem. Without [even] thinking, they are fine – their reaction. I believe that it is the feeling of being close to someone in a more intimate way… that creates the sense of being part of a community.

— Latino man, 31, Loma Linda

Real community came from feelings of mutuality and looking out for one another, courtesy and respectfulness, and knowing that someone will be there when needed. These were not coextensive with race/ethnicity in the way participants often initially expressed. Where they were felt in a neighborhood, school, or faith context, there was community. This way of conceiving community makes membership more open, but arguably more demanding; some of those who defined community in this way spoke of not having community, and a sense that it is lost to the “rat race” of a region where everyone is hustling to make ends meet.

Interestingly, several other residents took from this very same hustle a sense of oneness or community with people who they may not know, but who “get it.” Usually described through the idea of “struggle,” these residents see something binding in the common daily experience of working hard to make it in an unforgiving economic context. This shared struggle—not necessarily a shared project, but a “we” that struggles in the same way—is a resonant story of “us” across low- and middle-income communities of color in the Inland Empire.

Finally, some narratives from Black Inland Empire residents describe an absence of community in a way that highlights prospective intervention points for civic and community leaders. In focus groups with both African-American women and men, participants lamented the lack of a sense of community in their cities or neighborhoods. Their stories contained astute diagnoses of how limited economic opportunity is both precursor to, and consequence of, this missing community. First, the long work hours, commutes, and frequent moves that characterize low-income residents’ lives in the region make it difficult to form the kinds of bonds that cohere communities. In turn, the absence of these bonds means that there are few spaces through which Black residents can mentor, share personal connections, or otherwise lift one another up. Here, talk of an absence of community points to residents’ awareness of how interpersonal relations and networks serve as conduits of opportunity.40 The extension and density of those networks grant access, and their boundaries enclose privilege—a privilege that is racialized in the context of de facto racial segregation.41 “Community,” these Black study participants knew, is a critical piece of the infrastructure of economic mobility.

PARTICIPANT 1:

[T]his demographic, in this geographical area — understand that we don’t have a community.

PARTICIPANT 10:

We don’t.

PARTICIPANT 1:

We’re living in somebody else’s community.

PARTICIPANT 3:

We’re nomads.

— African-American men focus group

Conclusions and Implications

This part of the report has illuminated the extent to which the Inland Empire is a region of people in movement, and communities in formation. No community is ever static, of course. But those in the Inland Empire—living a prolonged period of far-reaching change, and for many, instability and unmet expectations—are perhaps more dynamic than most.

In particular, Part II spotlighted a number of holes left in the work of weaving the region’s population into what residents can feel and experience as a meaningful “we.” Whatever the demographic categories and figures tell us about the Inland Empire’s people, what that “we” will be remains undetermined. Neither “destiny” nor guaranteed, it will take the forms given to it by those who do the work of building it.

In our research with low- and middle-income people of color in the region, the desire for deeper community ties is strong. Talk of an absence of community was not cynical, nor driven by insularity or individualism. It came through in narratives conveying senses of loss and longing. Our research suggests that Inland Empire residents are ready to be more connected, and eager to be part of larger local collectives.

Study participants widely expressed commitments to doing their part as well. The ideas of remembering one’s personal roots (“not forgetting where you came from”), and giving back were widely resonant and universally lauded. So too was talk of “doing it for your city,” or for your community. And a particularly powerful variation on this was the repeatedly expressed idea that people should stand up for, and together with, those who are struggling in the same way, or who need support more than they do. Each of these offers lessons that could be applied in building new narratives of who “we” are in the Inland Empire.

While we have emphasized potential, none of the above is to say that population change in the region has been without tensions. In Part III, we turn to questions of inter- and intragroup dynamics in the Inland Empire, and what our research can teach about the prospects for bridging toward greater senses of community and belonging.

- 23 In the 1980s, the region’s western population center of Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario saw the fastest growth of any large metropolitan area in the country—growing by an astounding 66 percent. The metro area continued to be among the fastest growing in the 2000s. William H. Frey, “Population Growth in Metro America since 1980: Putting the Volatile 2000s in Perspective,” Metropolitan Policy Program, The Brookings Institution, 2012, p. 4.

- 24 Kfir Mordechay, “Race, Space, and America’s Subprime Housing Boom,” Urban Geography 41, no. 6 (2020): 936-946.

- 25 De Lara, Inland Shift, pp. 115-116.

- 26 Kfir Mordechay, “Vast Changes and an Uneasy Future: Racial and Regional Inequality in Southern California,” The Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles, UCLA, April 2014, pp. 22, 25.

- 27 Center for Social Innovation, California Immigrant Policy Center, and Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice, “State of Immigrants in the Inland Empire,” Center for Social Innovation, University of California, Riverside, April 2018.

- 28 Deirdre Pfeiffer, “African Americans’ Search for ‘More for Less’ and ‘Peace of Mind’ on the Exurban Frontier,” Urban Geography 33, no. 1 (2012): 64-90. This was the most recent, but not the first, Black migration to the Inland Empire. Following World War II as well, Black Angelenos sought social mobility inland, not only because it was more affordable, but also in response to discrimination in LA. Genevieve Carpio writes that, “Due to entrenched racial barriers in housing, African American suburbanization often required movement from Los Angeles to its outermost suburbs”—what was until recently a citrus belt, and in process of becoming the Inland Empire. See Carpio, Collisions at the Crossroads, pp. 20, 184.

- 29 Mordechay, “Race, Space, and America’s Subprime Housing Boom,” p. 939. On housing production in Southern California in the 1980s through 2010, see Pfeiffer, “African Americans’ Search for ‘More for Less’ and ‘Peace of Mind’ on the Exurban Frontier.”

- 30 Mordechay, “Race, Space, and America’s Subprime Housing Boom.”

- 31 For a meta-analysis of this body of literature, see Roy F. Baumeister and Mark R. Leary, “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation,” Psychological Bulletin 117, no. 3 (1995): 497-529.

- 32 john a. powell and Stephen Menendian, “Editors’ Introduction,” Othering & Belonging 1 (Summer 2016).

- 33 Baumeister and Leary, “The Need to Belong.”

- 34 This question was the first substantive item on the July 2020 survey, and was prefaced by the request that respondents “think back to the time before the outbreak of the coronavirus” when answering it. This was meant to gauge residents’ sense of belonging under “normal” circumstances, i.e. outside of those brought on by the—at the time—four month-old pandemic context. For complete results, see https://tinyurl.com/b4bie2020.

- 35 For the two-county Inland Empire region, overall, 75 percent of residents feel belonging “most” or “all” of the time in their neighborhoods; 72 percent in their workplaces (if applicable); 63 percent on the street or in other public places; and just 60.5 percent in schools (if applicable). See ibid.

- 36 Among Latino men, one third attributed their experiences of non-belonging to their race, and one third to culture or background, while a larger share of Latinx men than women said “don’t know.” Respondents were allowed to select as many characteristics as applicable from a list of ten: your age; your gender; your race; your culture or background; your height, weight, or physical appearance; your religion; your language or the way you speak; your sexuality; a disability; and other.

- 37 Juan de Lara, “The Last Suburb: Immigrant Integration in the Inland Empire,” in John Mollenkopf and Manuel Pastor, eds., Unsettled Americans: Metropolitan Context and Civic Leadership for Immigrant Integration, Cornell University Press, 2016, p. 140.

- 38 Median household incomes in Corona and Moreno Valley—other cities that are highlighted in Figure 6—are $84,000 and $66,000, respectively.

- 39 Of the 57 percent of Inland Empire respondents who said that they usually do not feel belonging in at least one setting, 36 percent said the reason was their race, 26 percent said their height, weight, or physical appearance, and 25 percent said their culture or background.

- 40 This local conception of community strongly echoes the concept of social capital.

- 41 Black focus-group participants made this observation, which has also been studied by, among others, Nancy DiTomaso, The American Non-Dilemma: Racial Inequality without Racism, Russell Sage Foundation, 2013.