This FAQ is was created to accompany our more robust legal guidance document, Advancing Racial Equity: Legal Guidance for Advocates.

- Is consideration of race in public policymaking or public programs illegal or unconstitutional?

- As a follow up then, what kinds of consideration of race are generally prohibited?

- What kinds of consideration of race, then, are generally permitted?

- What is the exact difference between “race-conscious” program and policy and “race-based”?

- What, then, is a “race-neutral” policy?

- What about the use of proxies? Is that race-based?

- If I use proxies or indicators that correlate with race, how can I protect myself from getting sued?

- Am I allowed or permitted to set numerical diversity goals or targets for my organization?

- What is DEI? And what are the differences in these ideas?

- As a follow up, what is the difference between “Equity” and “Equality,” in this context?

- In devising or implementing DEI programs or policies generally, or racial equity versions specifically, does it make a difference whether the institution or organization is public or private?

- How does the January, 2025 Trump Executive Orders affect what is permissible and what is not?

- What about race-conscious programming in educational contexts?

1. QUESTION: Is consideration of race in public policymaking or public programs illegal or unconstitutional?

ANSWER: Not categorically, no. The short answer is that some forms of consideration of race are prohibited or presumptively unconstitutional while others are allowed. It depends on how race is being considered.

2. QUESTION: As a follow up then, what kinds of consideration of race are generally prohibited?

ANSWER: Generally, any policy or program that considers the race of an individual in providing benefits or advantages, while not extending those benefits or affordances to individuals of a different racial group, will be prohibited. Thus, it is a presumptive violation of the law if any applicant, customer, contractor, or other entity is given a benefit or a boost (or, conversely, denied the same benefit or has a disadvantage imposed upon them) because of their race or racial identity.

3. QUESTION: What kinds of consideration of race, then, are generally permitted?

ANSWER: Any consideration or consciousness of race that does not advantage or benefit specific individuals because of their racial identity will generally be permitted. Thus, surveying people about their racial identity (like the decennial census form or fielding employee engagement surveys), collecting, tracking and analyzing racial data or statistics (including disparities), or general programming, such as diversity trainings or implicit bias trainings, are broadly permitted. These activities do not treat individuals differently because of their race. Additionally, programs aimed at members of certain racial groups or designed for members of those groups, but open and available for the benefit to all, do not violate the law. Examples of this include mentorship programs or other supplemental offerings that are available to all.

Furthermore, consideration of race is permitted in a variety of other ways as well, especially in a general way. Public institutions and entities can consider racial demographics or composition of their communities or neighborhoods in deciding where to direct investments or draw jurisdictional boundaries, such as in political districting processes or drawing school district attendance boundaries. Local governments or state agencies, for example, can study racial health disparities in deciding where to build new clinics or redirect health care providers or award grants or licenses. School districts can draw attendance boundaries and establish feeder patterns to promote racial diversity and integration. State legislatures are even permitted to consider racial demographics in drawing political district boundaries, as long as race is not the “predominant” factor, and they may even be required to do so in order to protect certain voting rights (such as avoiding vote dilution). Although such activities are clearly “race-conscious,” they are not “race-based.” The fact that they may have a disproportionate benefit on certain racial groups does not make them illegal.

4. QUESTION: What is the exact difference between “race-conscious” program and policy and “race-based”?

ANSWER: This is one of the most important distinctions provided in the guidance, and the difference is subtle and nuanced.

Race-based policies and programs or activities is the Supreme Court’s vernacular for describing decision-making that uses race at the individual level as a selection criterion, generally in employment, contracting, or education (i.e. hiring, promotion, procurement decisions, awarding contracts, or admissions). Thus, if a hiring committee or a faculty admissions committee gives applicants a boost or benefit because of their racial identity, that would be a race-based selection criterion.

Race-conscious programs and policies are a larger and broader category of activity than those that are merely race-based. They encompass and include race-based policies, but they also include those that are cognizant or aware of race, but do not use or consider race at the individual level as a criterion or selection factor.

To help people understand this distinction, the law professor Sonja Starr metaphorically characterizes the difference as between the “retail-level” use of race and the “wholesale-level” use of race. She also describes the difference as one of “means-colorblindness” versus “ends-colorblindness.” “Means-colorblindness” is generally prohibited, while “ends-colorblindness” is not.

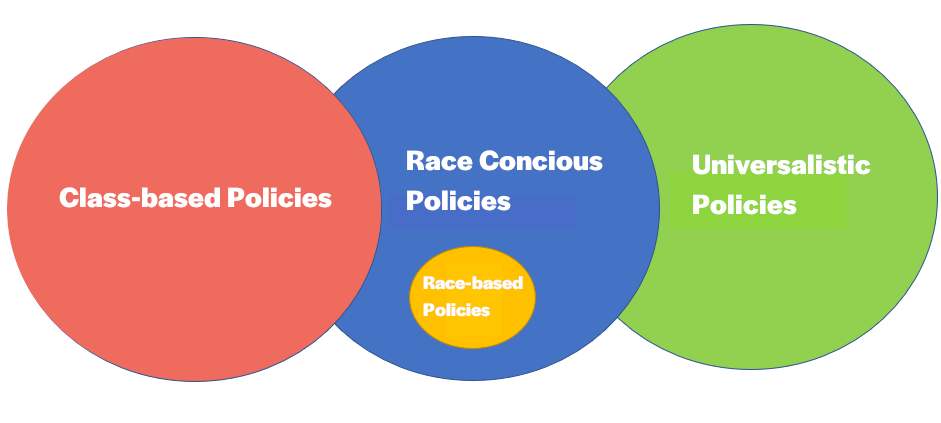

Because this difference is confusing and often conflated, I have created a Venn diagram graphic below to visually illustrate the distinction. All race-based policy making is “race conscious,” but not all race-conscious policy is race-based. As you can see from the graphic, “race-based” policies are a much smaller subset of race-conscious policies and programs.

5. QUESTION: What, then, is a “race-neutral” policy?

ANSWER: “Race-neutral” policies is a term that the Supreme Court uses to describe any policy that is not race-based, meaning that it does not entail racial classification of individuals, with benefits or burdens imposed because of that classification.

Race-neutrality does not mean that the policy is race-unconscious. Although many, perhaps most, race-neutral policies are not race-conscious (that have neither a race-conscious goal or purpose nor does their design or implementation have anything to do with race, at least not in the minds of the policymakers), many race-conscious policies are also race-neutral. A famous example is the Texas Ten Percent Plan, which the Supreme Court described as “race-neutral,” which was designed, in part, to promote racial diversity at the University of Texas.

Race-neutral policymaking then, is any policy that is not-race based. In the diagram below, everything but the yellow circle is technically “race-neutral.” Class-based policies, universal policies, and race-conscious policies that are not race-based are all technically “race-neutral.”

6. QUESTION: What about the use of proxies? Is that race-based?

ANSWER: It depends on what is meant by a “proxy” and how that idea is operationalized.

If the proxy is merely a cover or fig leaf for the actual consideration of the race of individuals, then the proxy is a subterfuge, and the policy will be presumptively unlawful.

On the other hand, if the proxy is honestly considered on its own, and consistently applied to all cases, people or circumstances, irrespective of the race of the individual, then it is not technically race-based, even if it (or in combination with other factors) is highly correlated with race. In several contexts, factors such as socioeconomic status, poverty, neighborhood poverty, educational attainment, formerly incarcerated status, and single–parent households have been used as considerations in permissible race-conscious policies.

Many non-racial factors correlate with specific racial-groups. They can generally be used to direct policy benefits disproportionately to particular racial groups. So long as those factors are not the race of individuals nor a subterfuge for the actual consideration of race of individuals, they should be broadly permitted.

The line is simple: consideration of race is not permitted at the individual level. If you are using non-racial factors that correlate with race, that is broadly permitted as long as you are not actually considering a person’s race.

There may be strange corner cases, however, where race is so highly correlated with a non-racial factor that a court might regard the use of it as a violation. If a genetic marker or specific ability or past condition were highly or perfectly correspondent to a racial group, then a review court might regard it as an inherent subterfuge.

An interesting question, in this regard, arose during oral argument in the Supreme Court’s most recent affirmative action case about whether being a descendant of American slavery (ADOS) was a racial criterion. Justice Kavanaugh said: “I'm just making sure what qualifies as race-neutral in the first place. What if a college says we're going to give a plus to descendants of slaves? Is that race-neutral or not?” The Court did not resolve the question, but justices noted that the status of being descended from American slaves is “bound up” with race.

The problem with using this status is that it is not perfectly correspondent with race or racial identity. As we know, many Black Americans, including Barack Obama, are not ADOS (American Descendants of Slavery).

Similarly, not all Chinese people speak Mandarin, and many non-Chinese people also speak Mandarin. Nonetheless, linguistic ability with respect to Mandarin is highly correlated with Chinese ethnic identity.

These are difficult questions to answer, and courts have not provided clear guidance. Technically, however, any criterion that is not race itself is not a racial classification, but a reviewing court might not always respect that distinction.

7. QUESTION: If I use proxies or indicators that correlate with race, how can I protect myself from getting sued?

ANSWER: The short answer is that you can’t. You can get sued for anything. The important question is not whether you can or will get sued; it is whether you will be liable or have an adverse judgment against you. Again, despite legal clarity, lower courts can also get things wrong.

The best thing you can do, if you want to pursue race-conscious policies and programming, is to clearly and consistently instruct your managers or employees to always and consistently avoid consideration of the race of individuals in any decision-making process. If your decision-making process includes several indicators that correlate with race, you should be exceptionally clear in both written materials/instructions and in training that decision-makers are to avoid any specific or particular consideration of race in making any judgment or decision. Consistently applied guidance in this regard will be important evidence in your defense in any suit. You can admit to having racial goals or purposes as long as you are clear in avoiding any use of race as a factor or criterion and therefore avoid claims of using impermissible racial classifications. As long as you pursue these goals with race-neutral methods and processes, you are on safe legal ground (as the law stands today).

8. QUESTION: Am I allowed or permitted to set numerical diversity goals or targets for my organization?

ANSWER: Yes. Nothing prohibits you from establishing goals or targets. You are only limited in the means by which you may achieve those targets. You can even establish specific quantifiable targets. The only restriction is that you are not allowed to use race-based means to achieve those targets.

9. QUESTION: What is DEI? And what are the differences in these ideas?

ANSWER: DEI stands for “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.”

These ideas are quite different, with separate and often disparate justifications, yet they are often combined in practice for organizational cohesion, synergy and simplicity. Unfortunately, this conflation has allowed critiques of one practice to extend to the other.

Diversity refers to programs or initiatives designed to increase the representation of underrepresented groups, and people of different backgrounds in certain organizations, institutions, departments, or units. The idea of diversity is not only or simply a practice to address exclusion, but is also widely believed to improve organizational culture and outcomes, by reducing groupthink, increasing access to different perspectives, and better representing the society in which organizations operate.

Inclusion refers to efforts or practices designed to remove or dismantle barriers that keep members of certain groups outside of institutions, organizations, departments, or units. Thus, inclusion occurs when organizations and institutions recognize that current rules or practices keep certain people out, either by design or inadvertently, and take steps to dismantle or alter those practices. This can be as simple as allowing women membership or admission to an institution that traditionally excluded them, or recognizing that certain features of your institution make it difficult for members of some groups, such as people with disabilities, the elderly, or pregnant women, to participate, because of the lack of accommodations, such elevators or ramps.

Equity refers to a broad spectrum of practices designed to improve outcomes for members of historically disadvantaged groups, or any social group or identity group. Equity differs from the concept of “equality” - or equal treatment - not, as some critics say, because it is solely or entirely concerned with equalizing outcomes. Rather, equity differs from “equality” because it brings into focus the fact that fairness and justice sometimes require different treatment. Accommodations for people with disabilities, child care, dietary restrictions, or illnesses, for example, are widely accepted in society and rarely disputed. Similarly, we treat people differently based upon their age, although this is not widely thought to be unjust. Differential treatment, on the other hand, for people on the basis of race, is highly controversial, although the justification and rationale is often the same.

10. QUESTION: As a follow up, what is the difference between “Equity” and “Equality,” in this context?

ANSWER: The difference between equality and equity lies not with its goals or intentions, but rather its implementation. Equal treatment treats everyone the same, and ignores differences in circumstance or situation - like whether someone is able-bodied or not, has access to a car, or can afford to pay a simple and ordinary fee. Although many policies are sensitive to differences (usually by targeting a specific group), equity policies and programs are broad efforts to try to better account for this blindspot, and provide different, but fair, treatment for all.

Fairness and justice sometimes requires treating everyone the same. And sometimes fairness and justice requires treating people differently. Equity recognizes the latter, while “equality,” as broadly understood, is often blind to this reality.

11. QUESTION: In devising or implementing DEI programs or policies generally, or racial equity versions specifically, does it make a difference whether the institution or organization is public or private?

ANSWER: It can make a difference, but in many cases it will not.

A “public” entity is one that is an instrumentality of government or the state. Examples include state and federal agencies, state and local governments, local school districts, public corporations, and public colleges and universities, among other entities. A private entity is an institution or organization that is not an extension of the state or government. Examples include small business and corporations (regardless of whether they are “publicly traded”), non-profit organizations, philanthropic organizations, and private social clubs.

The key question is who runs or operates the entity: If it is an arm of the state, then it is likely a public entity. But another relevant question is where the funding comes from. Some private entities, such as private research universities and hospitals, receive significant funding from the state. Similarly, other private entities, such as charities or philanthropic organizations, receive subsidies or tax-breaks from the state. In most cases, that subsidy, either direct or indirect, will not convert the entity into a public one.

In general, private entities have more leeway to design and implement equity policies. Private entities are still often subject to general civil rights laws, such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination in employment on a variety of bases, or Title VIII, which prohibits discrimination in housing. But they are generally not subject to Title VI or the equal protection clause of the US Constitution. And, they may not be subject to other state laws, such as California’s anti-affirmative action law, Proposition 209, which only applies to public employment, public education, and public contracting.

There is an unresolved legal question about whether completely private entities that are not subject to Title VI and are not discriminating in hiring or housing may nonetheless be challenged in court for grantmaking in a targeted or race-based way under § 1981, a reconstruction era civil rights statute that prohibits discrimination in making contracts. One federal circuit court of appeals ruled last year that that provision does not apply to private philanthropy, but that ruling does apply outside of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia.

Entities that are “public” or receive federal funds are subject to Title VI, which is why Harvard was sued for its affirmative action policies, even though it is a private institution outside of the scope of the equal protection clause.

12. QUESTION: How does the January, 2025 Trump Executive Orders affect what is permissible and what is not?

ANSWER: It should not, although the scope and ultimate effect of the orders is not yet clear. It seems to mischaracterize DEI programs and practices in several critical ways.

The first executive order (EO) that Trump issued on this topic is entitled “Ending Radical And Wasteful Government DEI Programs And Preferencing.” This EO directs the heads of federal agencies and departments to catalog and terminate all non-mandatory DEI offices, positions, and programming, including that provided by contractors. It does not make such programming illegal. It just directs the federal government to stop doing such activities.

The second EO that Trump issued on this topic is entitled “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity.” This EO makes clear the position of the President that DEI programs and practices are “immoral” and a form of “preferences.” The order directs government officials to “terminate all discriminatory and illegal preferences, mandates, policies, programs, activities, guidance, regulations, enforcement actions, consent orders, and requirements.” It also directs all agencies to “combat illegal private-sector DEI” programming and activities.

The EO seems to assume what it concludes. Since most DEI programs are not technically “preferences” nor “discriminatory,” it is unclear what the scope or effect of this order actually will be. Presumably, all previous DEI programs were neither preferences nor discriminatory, or else they would and could have been challenged in court.

The EO also terminated a long list of previous EOs relating to affirmative action and DEI practices. The immediate effect will be to chill DEI programs across the country, and to terminate those that were undertaken within the federal government, but it does not appear to redefine what is illegal and what is permissible under the constitution or statutory law.

13. QUESTION: What about race-conscious programming in educational contexts?

ANSWER: The Trump administration issued another EO entitled “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling.” The scope of the order is technically restricted to K-12 education and institutions receiving federal funds. It identifies certain precepts that it associates (not always correctly) with DEI programming, and then makes it the policy of the federal government to terminate and defund such programs and to develop a strategy to “end the indoctrination” of the ideas that underpin such programs.

The EO characterizes “equity” programming as “discriminatory.” But if it were already illegal, then this EO would have been unnecessary. Suits brought to challenge previous practices would have been successful. So the likely effect is not to change the law, but to discourage institutions from engaging in such programming.

Furthermore, the EO identifies certain precepts that it regards as particularly problematic. Examples include “an ideology that treats individuals as members of preferred or disfavored groups, rather than as individuals,” “An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race, color, sex, or national origin, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously,” and “the United States is fundamentally racist, sexist, or otherwise discriminatory.” This list of precepts is similar to an EO Trump issued in 2020 entitled “Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping.” Although lawsuits were brought to challenge that order (which was, in my view, patently unconstitutional), that order was rescinded by the Biden administration before a major decision had been given.

Once again, one of the problems with this order is that most DEI programs, like most Diversity programs identified in the 2020 EO, do not endorse these ideas, at least not as specifically framed here. But often not in spirit either. That does not mean that some educational DEI programming does not promulgate such precepts, but it would be an overgeneralization to say that all or even most do.

Also, public schools in the United States are principally under the control of state and local governments, and federal funding, through Title I, is controlled by Congress, not the President. Therefore, it is unclear to what extent the EO here will have any effect aside from chilling or discouraging such programming.

As a follow up to these executive orders, the Trump administration’s Department of Education issued a “dear colleague” guidance letter on February 14, 2025. This letter, although broadly correct in its interpretation of law, has a few inaccuracies. It correctly notes that “race-based” decision-making is unlawful. It is also correct that the use of race-proxies can be unlawful, if as noted above, those proxies are merely covers for race-based selections or considerations.

Where the letter is incorrect, as a statement of law, however, is to assert or imply that any race-conscious programming is unlawful whenever there are racial motivations. As long as the proxies or correlates do not lead to the actual consideration of a person’s or individual’s race or assumptions about their race, then that is not, legally and technically speaking, “race-based.” Thus, the letter is incorrect in its conclusion that it is “unlawful for an educational institution to eliminate standardized testing to achieve a desired racial balance or to increase racial diversity.” As long as no individual applicant’s race is actually considered, or presumed and then considered, in the evaluation of the applicant, race-neutral factors that are assumed to increase racial diversity are broadly lawful.

On March 1, the Department of Education issued an FAQ that appears to soften or backtrack on some of the elements just noted. The guidance in the FAQ hews much more closely to established law.

In the interim, there have been several legal challenges, and although litigation is ongoing, several federal courts have already blocked the letter as viewpoint discrimination.

If you have more commonly asked questions, please feel free to email us to consider adding them to this FAQ.