< previous page | home page | next page >

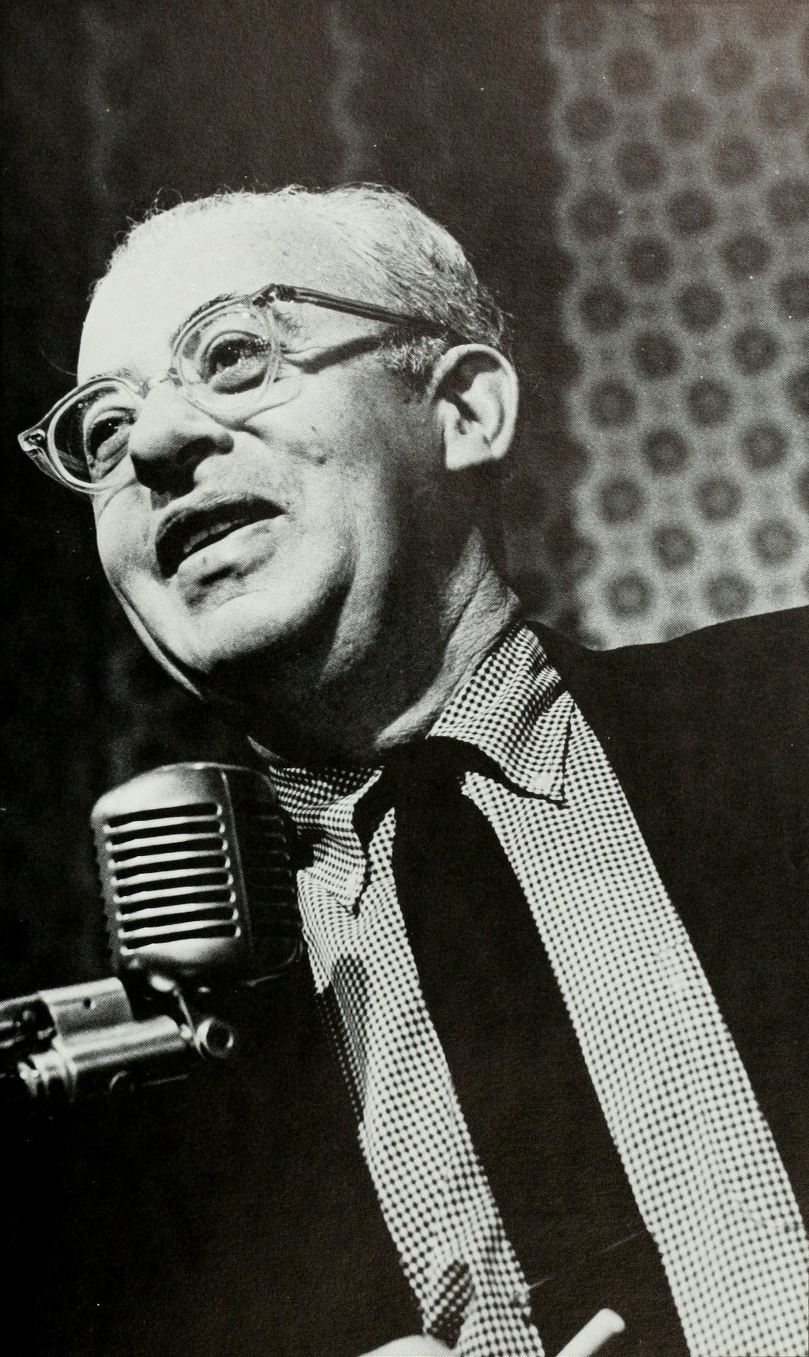

Background and History of Saul Alinsky

Saul Alinsky was a native of Chicago, a vital manufacturing and transportation hub for the country in the 1930s. Scores of meat packing companies, warehouses, and train lines converged on the Second City and employed thousands of working-class white ethnics and African Americans, all escaping poverty, violent oppression, and exploitation from somewhere else. While Alinsky was not a devout practitioner of religion, his Jewish identity served as an essential reference point for his work – dealing with discrimination, being forced to live in slums, and being paid low wages – within a multiracial context.

Saul Alinsky was a native of Chicago, a vital manufacturing and transportation hub for the country in the 1930s. Scores of meat packing companies, warehouses, and train lines converged on the Second City and employed thousands of working-class white ethnics and African Americans, all escaping poverty, violent oppression, and exploitation from somewhere else. While Alinsky was not a devout practitioner of religion, his Jewish identity served as an essential reference point for his work – dealing with discrimination, being forced to live in slums, and being paid low wages – within a multiracial context.

Jewish and a native of Chicago during a time of increased labor militancy in the late 1930s and the 1940s, Alinsky came to adopt an organizing approach that seemed to counter broader tactics of the Communist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). He focused on developing local leaders to confront local decision-makers – the boss, the landlord, the politician – and extract concessions. Alinsky believed that this practical approach and emphasis on self-interests would empower and unify communities.

The Alinsky Model of Organizing

The Alinsky model of organizing centers on identifying and confronting issues within a community and addressing them in the public sphere through development and organizing. Community members participate, lead, and engage in change-making, rather than acting as observers. At its core, the model utilizes building relationships as central to building enough power to effect change.

The process starts with one-on-one encounters initiated by organizers, which are strategic conversations that begin relationship building and surface common issues. Then it moves toward issue research and community listening sessions. The final component is research sessions between elected officials and key stakeholders within a community. The goal is to understand how power moves, who may benefit from the status quo and to build relationships with those with enough power to make a change. At this point, the community is ready to move into action. Once a problem is identified during listening sessions and dissected into a singular issue via research, public action is taken to build power among leaders, present solutions, and build commitment to those solutions.

One of the first examples of this organizing model was the creation of the Back of the Yard Neighborhood Council located on Chicago’s South Side. BYNC was a multiracial, multiethnic organization that fought for workers’ rights in the meatpacking industry and tenants’ rights. (Many years later, however, BYNC fought against housing integration.)

Not completely dismissive of broader issues, the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) was created by Alinsky and others in 1940 to connect a network of community-based organizations throughout the nation. The structure of IAF is similar to a national union’s relationship with its locals. In the end, Alinsky

saw the development of local leaders confronting local decision-makers to win concessions that were important to them as the best path toward a more just and fair society.

A contemporary example of the model at work within the PICO California organization, which follows the Alinsky model of organizing, is a community benefits agreement that was reached between the city of Sacramento and Sacramento Area Congregations Together (Sac ACT) in 2017. City officials ushered in the building of a new basketball arena in the downtown corridor that would cause further gentrification in the city. With housing costs rising rapidly, displacement occurring, and job loss increasing among the most marginalized residents, Black faith leaders were able to organize the community and contest with the owners of the Sacramento Kings, the Building Trades Union, and city officials so that the new development would not further exacerbate community suffering.

The community benefits agreement ensured a certain percentage of new jobs in the arena would go to individuals from the impacted communities. This course of action did not solve all of the issues plaguing the community. But it demonstrated how much power can be leveraged when a community is organized and deeply engaged in defining solutions. The faith leaders and community members involved built upon this win when the City Council passed an ordinance that an allotted percentage of jobs for impacted communities must be included in all publicly funded development.

Labor and Alinsky

Many unions throughout the decades have employed organizing approaches that came to define the Alinsky model. Furthermore, it is important to understand that labor organizing in the U.S. predates the work of Alinsky. The history of unions typically began with a group of workers banding together to address problems specific to their worksites. Draymen (truck drivers who deliver beer) in San Francisco’s fight for fair pay in the 1850s gave birth to the Teamsters Union. Electrical workers came together at the 1890 St. Louis Exposition to organize what became known as the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW).

This practical approach dominated the national labor movement led by the American Federation of Labor (AFL), formed in 1886 to unite white laborers in local craft unions. While Alinsky had a relationship with John Lewis, the leader of the more radical Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which sought to organize workers by industry rather than just worksites, Alinsky seemed to take inspiration from the AFL’s emphasis on localized workplace action.

However, this privilege to focus almost exclusively on local worksite issues was not a possibility for non-white and non-male workers. The exploitation of Black workers was and continues to be tied to a system of systemic racial exclusion. Therefore, when the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was formed in 1925, it was essential for the union to fight simultaneously to end racism and ensure its members fair wages and safe working conditions.

Success & Implications to Bridging in the Model

Success within the Alinsky model comes with a leader’s ability to learn, understand, and practice the model, and move action through the cycles. This is as important as a policy win. This is also where bridging can take place. When leaders feel empowered through organizing, they are often put through an experience of building a sense of belonging to their community, organizations, movements, and ultimately themselves; and recognizing their connection to other communities, organizations, and movements. This awareness is then extended to others facing the same problems through their organizing journeys. Often, leaders discover that issues impacting their community also impact other marginalized communities, and when they join forces in addressing these issues, they build relationships across differences and shared identities.

The example of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters underscores the challenge to the labor of attaching the Alinsky model’s “insistence on organizing around local interests”, especially for those unions that organize women and men of color. A housekeeper who is an immigrant living in Los Angeles faces exploitation at the worksite and dangers related to their citizenship status. An African American who works as a security officer in Atlanta struggles with low pay rates that are connected to the anti-Black racism pervading every institution in this country. Many unions in the modern day have decided to shift away from an exclusive focus on workplace fights and are dedicating time and resources to address broader societal issues like anti-Black racism, criminal justice reform, climate change, immigration reform, and health care access.

Though relationship building across differences can be a result of the relational nature of the model, some of its limitations to bridge more deeply stem from the model’s origin. An explicit racial justice analysis is absent in the model, which leads to serious impediments to bridging differences. It promotes a color-blind approach that hurts those at the margins. A racial justice analysis allows space for the intersection of issues. While organizations and networks that ground themselves in the Alinsky model have made progress in addressing this, it’s important to name the origins of the gap they’re working to fill.

In 2014, The Raise the Wage Campaign fought to pass $15 minimum wage policies in Los Angeles City and County. While this union-led effort won historic victories that impact over 1 million workers in Los Angeles County, the vast majority of those benefiting are not members of unions. Contrary to the Alinsky approach, the campaign did not engage specific neighborhoods or conduct opinion surveys to drive the decision to act. Rather, the leadership decided to act and leveraged the power of the regional labor movement to successfully push elected officials to pass what was the largest wage increase policy in the country. The campaign helped to foster an identity as low-wage workers across the color line, while, at the same time, primarily benefiting those folks disproportionately at the very bottom, i.e., workers of color. It should be noted that labor unions must continue to address local workplace issues experienced by members. Many unions do not approach their work in the way described above. Some unions, like those often found in law enforcement or industrial settings, reflect more conservative views and approach their work in a more Alinskian manner. These are tensions that have always existed within organized labor and will remain. But an increasing number of unions are adopting an organizing approach that is more national and international in scope, ideologically more progressive, and driven by the global realities of people of color and women.

So, it may be more accurate to state that Alinsky adopted a method of organizing based on what he learned from labor organizers in the first half of the 20th century. The approach of local entities bringing together self-interested individuals and organizing them around practical issues was the key lesson he learned from the labor movement.

Since the model originates from a local focus with a four-step formula for making change, it has been experienced by people as rigid instead of adaptive or emergent. This experience can reduce people’s feeling of belonging because they are asked to adapt to the model rather than the model adapting to the people. This often results in a slower pace of organizing and leads to more incremental change. Over the past ten years, the PICO California Network has grown to be more engaged in movement strategies but there can still be a point of tension, i.e., when to use the tactics of Alinsky organizing and when to respond as a broader movement.

While federations in the PICO California Network have evolved to create more opportunities for learning that center people who are most directly impacted by inequality and injustice, this shift has resulted in slower paces of organizing and has not always translated to a policy win. Ultimately, lending itself to incrementalism. The expertise and authority come from people with experience in pursuing the model, not from people who directly experience the brunt of the problem in their everyday lives, and who want to try the innovation. The attributes contribute to a model that is unable to move from a rigid framework to a bridging and belonging model which centers on adaptation and evolution.

To continue building on the work and progress of both community organizing efforts and labor union organizing, a focus on bridging across differences and fostering belonging is necessary to center the voices and needs of marginalized community members and workers. This necessitates an adaptation of an Alinsky model centered on belonging as both in the self-interest of communities and workers, and the broader collective interest.