Boasting a reputation as a progressive stronghold and a sanctuary state, Californians pride themselves on inclusive cultural attitudes and regard their state as a hub of the “resistance” to the Trump administration’s exclusionary policies. Yet California is one of the most economically unequal states in the country, with the highest poverty rate and homeless population in the country, and features persistent and endemic racial and economic residential segregation.

After years of escalating pain, California’s housing crisis finally landed on the state’s legislative agenda in a big way two years ago, with several bills becoming lighting rods. A much broader and more robust set of housing bills were proposed last year. The legislative session that ended this past August was one of the most tumultuous in recent years, but ultimately resulted in notable accomplishments responsive to the housing crisis while promoting racial and economic equity.

In the same year that the Trump administration pursued a rollback of the nation’s federal fair housing laws and regulations, the California legislature stepped in to try and repair the breach with three bills, each of which were developed in partnership with several co-sponsoring organizations—including the Western Center on Law and Poverty, Public Advocates, and National Housing Law Project (AB 686); the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation (AB 1771, along with WCLP), and the Bay Area Council and Silicon Valley Leadership Group (SB 828). Courageous California legislators, working with their community partners, can be proud of these accomplishments.

The federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 not only prohibited discrimination in housing, but also included language that required the federal government to “affirmatively further fair housing.” Although this concept was left undefined, the Obama administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development promulgated an administrative regulation defining this responsibility. The rule required the federal government to work with local housing authorities and other jurisdictions to identify barriers to integration, and proactively work to address them, even at the threat of losing federal funds. The Trump administration has sought to weaken and roll back this rule.

The California bill AB 686 codifies California’s commitment to “affirmatively further fair housing” through “active government efforts to dismantle segregation and create equal housing opportunities.” Under the new law, every city and county must develop a fair housing assessment, which must be included in the housing element of the jurisdiction’s general plan, and establish policies and programs that affirmatively further fair housing. With these policies and programs codified in the housing element of each jurisdiction’s general plan, citizens and the state government can hold localities accountable to their fair housing commitments.

The Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RNHA) is one of California’s most significant policies for advancing housing equity. RHNA is California’s version of a “fair share” law, which requires cities and other jurisdictions across the state to provide their “fair share” of affordable housing. Unlike the so-called “Mount Laurel” plan adopted by New Jersey, which requires every jurisdiction set aside a small percentage of new housing for low-income and moderate-income residents, RHNA requires planning for five different income levels. In that regard, RHNA is, in principal, a more nuanced and stronger overall approach.

Unfortunately, RHNA hasn’t always worked as intended. In our 2017 report on RHNA, we examined the mechanics of the RHNA allocation process and found that the Bay Area RHNA methodology produces disparate racial impacts. Our research found that local governments with higher percentages of white residents were more likely to have received lower allocations of moderate and lower income housing, which may continue the pattern of

underproduction of affordable housing, and thus racial and economic exclusion, in such jurisdictions.

Not only do local jurisdictions fail to zone sufficiently for lower and moderate income residents, or would-be residents, but their methodologies tend to undercount projected growth, and RHNA fails to hold jurisdictions accountable for the backlog of underdevelopment. In 2008, New Jersey Governor Jon Corzine signed a bill that closed a loophole in the Mount Laurel policy, which allowed wealthier jurisdictions to pay for their “share,” but a court recently ruled that jurisdictions were required to make up the backlog they should have produced while fighting the law. An effective RHNA law in California needs the same level of enforcement.

Given these problems, we applaud a pair of bills last term (AB 1771 and SB 828) to reform the California’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) process. AB 1771 strengthens RHNA enforcement by creating greater equity, transparency, and accountability in the RHNA process. It requires regional councils of government (COGs) to employ more rigorous, data-driven RHNA methodologies that account for factors that more accurately project jurisdictions’ affordable housing needs. For example, cities must evaluate and account for “jobs-housing fit”–meaning the extent to which a jurisdiction has enough housing that is affordable to low-wage workers employed within its boundaries.

The new law also requires the California Department of Housing and Community Development to evaluate whether COGs’ methodologies comply with fair housing law. AB 1771 thus bolsters AB 686 by better ensuring that all communities–including historically exclusionary communities –are actually allocated a fair share, and in concert with bills passed in 2017, create greater enforcement of RHNA obligations. If a COG’s methodology is found to not affirmatively further fair housing, governments and citizens have legal recourse for challenging it. And finally, AB 1771 explicitly requires COGs to conduct a survey on fair housing, seeking to “overcome patterns of segregation and foster inclusive communities free from barriers that restrict access to opportunity based” on race.

Although watered-down, the final and ultimately enacted version of SB 828 also accomplishes some positive things. First, it requires jurisdictions to consider vacancy rates and housing cost burden as part of the methodology, two important considerations that should be part of the analysis. Second, it prohibits jurisdictions from using prior underproduction to justify continual foot dragging. And third, it refocuses on projected population growth, not simply existing demographics.

The most controversial bill of the 2018 term was SB 827, which would have overridden local zoning to promote density nearby public transit infrastructure. The goal of the bill was to overcome local opposition to generate the housing production needed to meet surging demand, and included scaling affordability requirements and mandated inclusionary levels to expand housing affordability. The bill failed to pass out of committee, despite receiving the greatest degree of attention and national press coverage, while the bill’s sponsors promised to bring the bill back in the next term.

In the aftermath of the bill, a few organizations have published analyses attempting to assess the possible effects of the bill, had it passed. Our friends at the Urban Displacement Project (UDP), for example, recently published a report assessing the types of neighborhoods impacted in terms of risk or stages of gentrification, the quality of the neighborhoods in terms of “resources,” using a methodology we co-developed, and projected the number of housing units that would be developed as a result of the bill, including the quantity of affordable units. They found, for example, that the bill “would have produced a six-fold increase in financially-feasible market-rate housing capacity and a seven-fold increase in financially-feasible inclusionary unit capacity.” Perhaps even more importantly, the locations of these units would be opportunity-enhancing. They found that “SB 827 would have increased financially feasible development potential for market-rate units six-fold in the high and highest resourced areas of the region (from 130,000 units to about 820,000 units).”

Although we found that many communities that would have been upzoned were high or very high resource neighborhoods, including Orinda, Lafayette, Tiburon, Novato, Burlingame, Millbrae, Belmont, Atherton, Redwood City, Mountain View, and others, the UDP researchers noted that nearly “half of the developable land in the Bay Area that would have been subject to SB 827 was in areas experiencing gentrification and displacement pressures or that were at risk of gentrification.” Moreover, they found that “60 percent of the net new financially-feasible unit capacity would have been located in low-income and gentrifying areas.”

Subsequently, and following the development of our recently published segregation report, which mapped the level of segregation experienced in every census tract in the Bay Area, we were able to examine the proportion of tracts that would be targeted by SB 827 that lay in each segregation category.

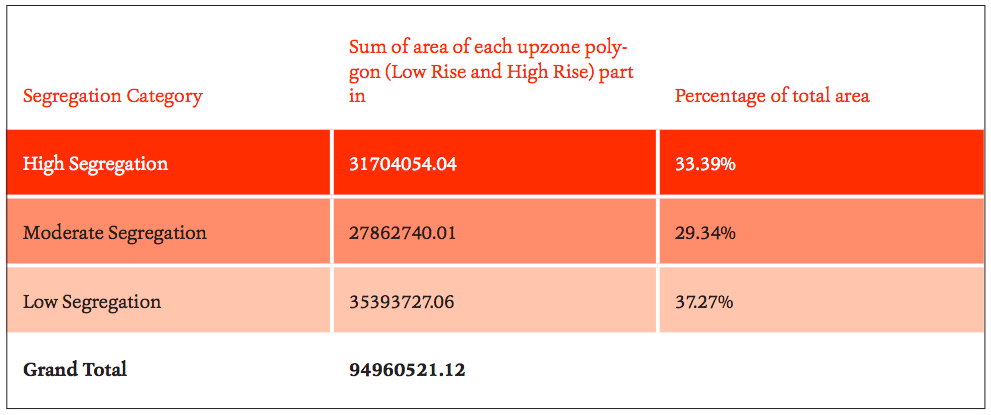

The chart below shows that disproportionately more segregated neighborhoods would be affected by SB 827.

The foregoing opportunity and segregation analysis is limited to the extent that we cannot project or know exactly who would move into new housing units constructed in each of those areas. But the inclusionary zoning requirements suggest that many low income people of color would have ample opportunities to move into higher opportunity, yet racially segregated neighborhoods in many of the places mentioned above, including places like Lafayette.

Although the federal government under the leadership of President Trump and Housing Secretary Ben Carson has not only stepped back from the goal of promoting racial equity in housing, but demonstrated hostility to that cause, California policymakers have shown a willingness to compensate for federal passivity and hostility. They must now build on the accomplishments of the last term and the work being done by researchers and advocates at the local and regional levels to understand and address the problems we face.

At a minimum, this means building new housing at all income levels, including for greater affordability, protecting tenants from displacement, strengthening RHNA, and continuing to hold the federal government accountable for its duties under federal law. More than a dozen new bills have already been introduced or announced for this year, including a revised version of SB 827, now known as SB 50. Unlike SB 827, this bill will target high resource, job rich communities that are not proximate to transit, and also exempt “sensitive communities.”