Download a PDF of this publication.

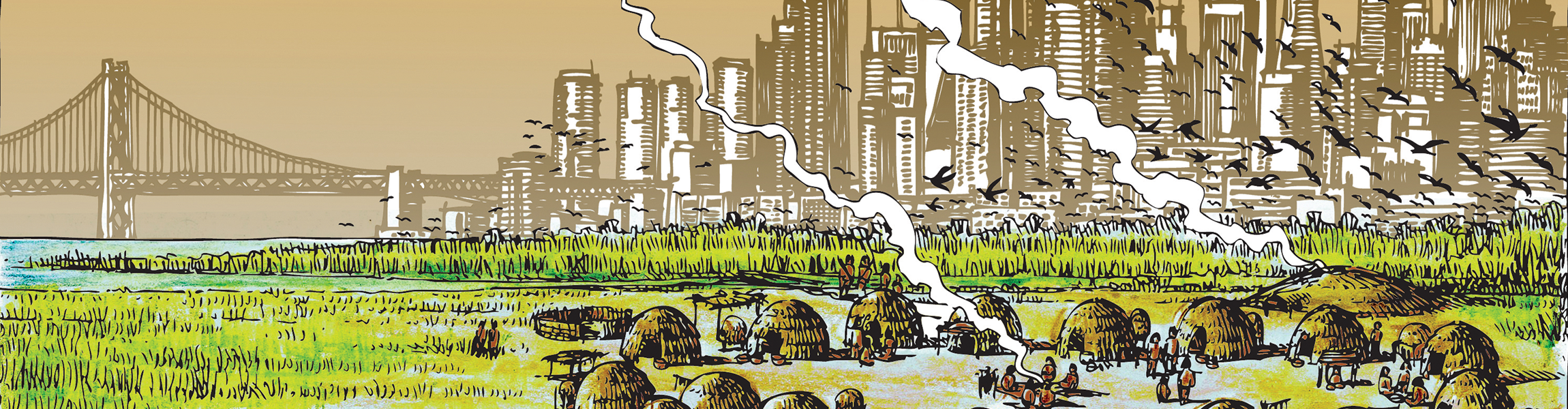

The rampant displacement seen today in the San Francisco Bay Area is built upon a history of exclusion and dispossession, centered on race, and driven by the logic of capitalism. This history established massive inequities in who owned land, who had access to financing, and who held political power, all of which determined―and still remain at the root of deciding―who can call the Bay Area home.

To grasp what it will take to undo racial inequality in housing, we must first understand how it was established and perpetuated. In this newly released report, we trace the roots of the region’s racial exclusion in housing and find that racism reinvents itself, proving to be dynamic, generative, and fluid, yet also remarkably durable and entrenched. The historical record also reveals that while racialized housing inequality in the Bay Area is part of a national dialectic, it is not solely a function of factors outside of local control. This report focuses specifically on the local: the many tactics of exclusion and dispossession that were deeply localized in practice, driven by local actors such as homeowners’ associations and neighborhood groups, real estate agents and developers operating within the regional housing market, and institutions, such as local governments and public agencies, which collectively shape local policies and markets, thus blurring the lines between public and private action. The constellation of exclusionary tactics discussed in the report―which includes state violence and dispossession, extrajudicial violence, exclusionary zoning, racially restrictive covenants and homeowner association bylaws, racialized public housing policies, urban renewal, racial steering and blockbusting, and municipal fragmentation and white flight―show how local laws, practices, and campaigns that first took hold in the Bay Area later came to inform state politics as well as other localities throughout the country.

We document this local history in order to ask: what does this mean for how we move forward as a region? As we reflect on the 400 years of resistance to slavery and injustice nationally, this examination of our local history brings questions of reparations and housing justice closer to home. How can we directly confront the roots of exclusion, provide restitution for historical racial injustices, and transform the power structures that continue to perpetuate them? How can we transform our institutions of local governance, zoning ordinances, housing markets, systems of property rights, connection to land, and relationships to our neighbors in order to fully realize racial equity and belonging?

We hope this report sparks conversation about these questions, and we invite you to share your reflections with us by email (HousingOBI@berkeley.edu), or on our social media channels.

Introduction

In 1952, Sing and Grace Sheng, a Chinese American couple living in San Francisco’s Chinatown district, decided to move out of the crowded apartment they shared with their extended family and find a place of their own. Since Mr. Sheng worked as a mechanic for Pan American Airways at the San Francisco airport, they looked for a home near his work in San Mateo County. They found a house in Southwood, a subdivision of South San Francisco, and signed a purchase agreement for $12,300. When white neighbors learned that a Chinese American family planned to move to Southwood, they protested the purchase. The South San Francisco city manager, Emmons McClung, also a Southwood homeowner, orchestrated a community meeting in which Mr. Sheng was confronted by 75 white homeowners opposed to his family moving into their neighborhood. They conveyed to Mr. Sheng that they had “no personal animosity toward him,” but feared that their property values would decrease if the neighborhood lost its status as “restricted”—or, for whites only.

The Southwood subdivision’s builder, American Homes Development Company, had stoked their fear, sending a letter to homeowners that urged them to protect their private property rights and the original restrictive covenants, despite the 1948 US Supreme Court decision that ruled them legally unenforceable. The company also reportedly attempted to intimidate the prior owner of the residence, J. H. Denson, who made the sale to the Shengs. Denson stated in an interview that the company called him and explained that “the whole neighborhood could bring suit” against him and that his business could be “blackballed.” Mr. Sheng responded by proposing a neighborhood vote on his purchase and promised he would not move in if the community voted against it. The city paid for and printed ballots to vote on the Shengs’ purchase. Southwood voted to exclude the Shengs, 174-28.1

The gentrification and displacement happening in the San Francisco Bay Area today may seem far removed from the blatant racial discrimination that the Shengs faced in the 1950s, but these stories are deeply connected. While the booming tech sector, globalized finance, and other forces shaping housing in the region are new, racial exclusion in housing is not. The region’s past and present are both stories of a system of racial capitalism, in which race and racism are fundamental to the creation of profit and accumulation of wealth.

photo: Sing Sheng (left) addresses the crowd of Southwood residents after City Manager Emmons McClung (right) records the results of the vote. The board displays the final tally; 174 out of 202 residents objected to the Sheng family moving into Southwood. Courtesy of San Mateo County Historical Association Collection (SMCHA 2017.54).

The rampant displacement seen today in the San Francisco Bay Area is built upon a history of exclusion and dispossession, centered on race, and driven by the logic of capitalism. This history established massive inequities in who owned land, who had access to financing, and who held political power, all of which determined—and still remain at the root of deciding—who can call the Bay Area home. While systems of exclusion have evolved between eras, research indicates that “it was in the early part of the twentieth century that the foundation for continuing inequality in the twenty-first century was laid. By building inequality into the physical landscape, cities added ‘unprecedented durability and rigidity to previously fragile and fluid [social] arrangements’.”2

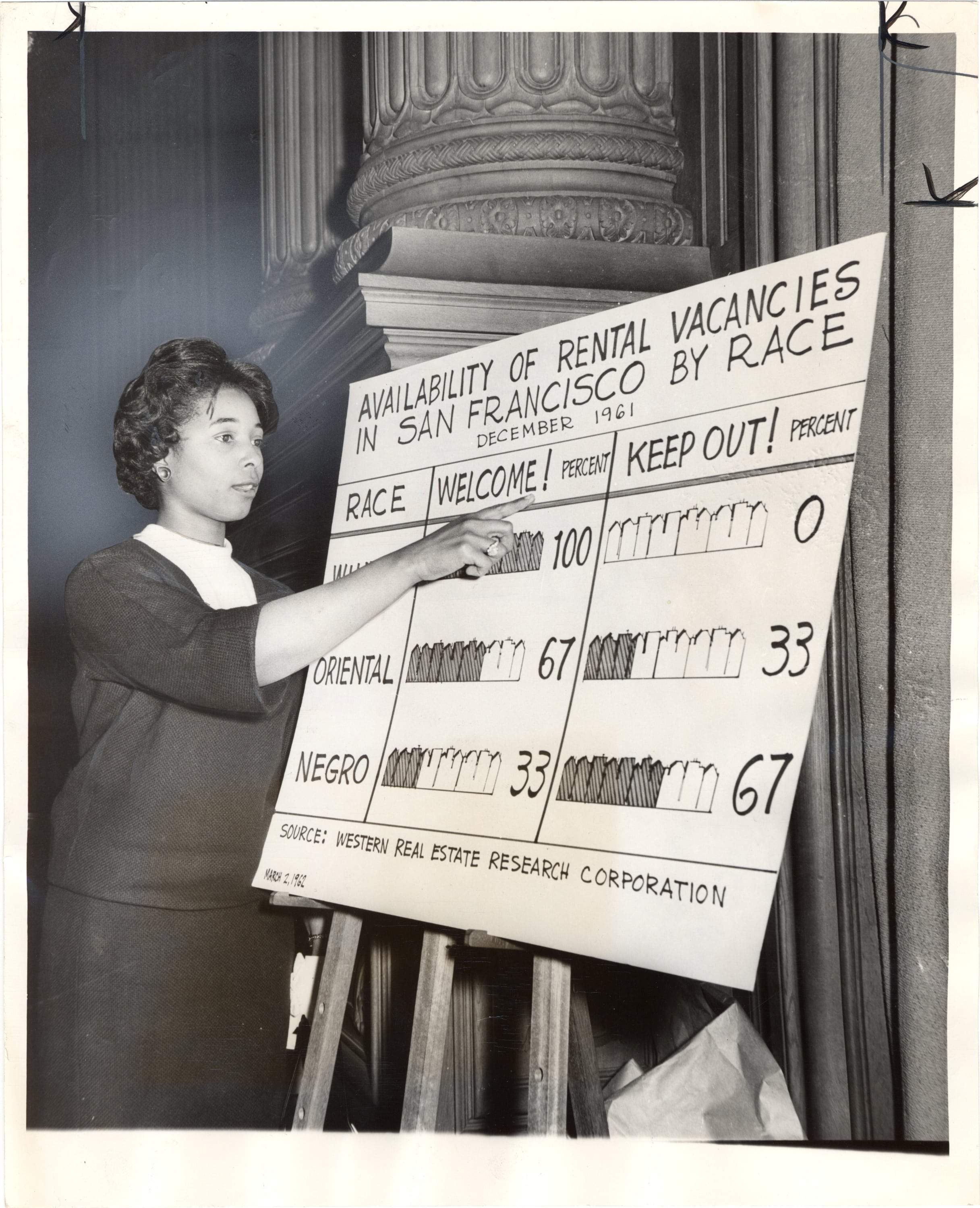

The lasting impact of these historic processes is clearly evident in the Bay Area, where racial residential segregation levels have persisted and, by some measures, even worsened since the 1970s.3 People of color in the region today still have far less wealth, less access to resources like high-quality schools and job centers, and lower rates of homeownership than white residents.4 Individuals and communities have resisted racial exclusion in housing through organizing, legal challenges, individual acts, and other means.

Organizations with deep roots in Bay Area communities led efforts to shift public opinion, call out injustices, and fight for fair and affordable housing, locally and nationally, while also defending individual families facing racial violence in their own neighborhoods. As part of the national civil rights movement, many Bay Area racial justice advocates contributed to the legal victories that overturned some exclusionary tactics. Yet despite the progress won by these movements, and the formation of many civic action and social justice groups pushing for racial inclusion and equity in the years since, the region has failed to undo racial inequities entrenched in earlier eras and is now perpetuating new ones.

Where do we go from here? To begin to answer this, and to grasp what it will take to undo racial inequality in housing, we must first understand how it was established and perpetuated. While our efforts to build a more equitable future naturally orient us toward the “new”— new policy solutions, technological innovations, new development—we cannot move forward without confronting the past. In tracing the roots of the region’s racial exclusion in housing, we find that racism reinvents itself, proving to be dynamic, generative, and fluid, yet also remarkably durable and entrenched. This report documents the multifaceted tactics for racial exclusion and dispossession in housing that changed over time and were carried out by various public institutions, business interests, and networks. Understanding the history of how these tactics functioned is essential to dismantling their legacies in the future.

Local Expressions of Broader Systems

Housing inequality and race before 1968 are often talked about in terms of racial residential segregation, with segregation understood as simply a separation of people of different racial groups. But this definition falls short of describing the actual effects of segregation or the actors, interests, and systems behind it. Segregation extracts wealth and creates barriers that exclude people of color from various resources. It functions to hoard these resources among the groups that are included and restrict the access of the excluded groups. Segregation meant that African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinx people, Native Americans, and other people of color were excluded from access to economic and educational opportunities, public investment, and other resources essential for building wealth, owning land, and attaining equitable economic power. Combined with forces such as overpolicing and fiscal austerity more broadly, it meant that historically segregated neighborhoods that confined people of color were undervalued, and their residents, who tended to be either low-income renters or highly indebted homeowners, were more likely to face unstable housing conditions.

Segregation is simultaneously a cause of racial inequity and an effect of broader racialized systems of dispossession, including predatory investment (such as urban renewal) and disinvestment (such as white flight) that allowed for capital accumulation for some through the extraction of wealth from others. Financial benefits of racial residential segregation accrued not only to white residents with concentrated resources in their neighborhoods, but to the local real estate developers, agents, and investors who employed lucrative strategies such as blockbusting, racially restrictive subdivisions, demolition and redevelopment, and expropriation of land. Historian Destin Jenkins describes segregation as “the domestic expression of the racial capitalism of the 20th century,” with “government as the vehicle and capitalism in the driver’s seat.”5 The exclusion of the Sheng family from South San Francisco is just one example of how this dynamic played out over the course of the region’s history. Along with the other cases detailed in this report, it illustrates how a multitude of actors successfully merged public and private capacities using a racial logic of difference not only to justify, but to actually drive the accumulation of capital through real estate by those in power. Within the system that these tactics upheld, boundaries between “public” and “private” must therefore be reconsidered. The “private” is more than individual choice, belief, and action, as Jenkins points out,6 while the “public,” often acts in the private interest of select property owners.

Local Actors and Tactics

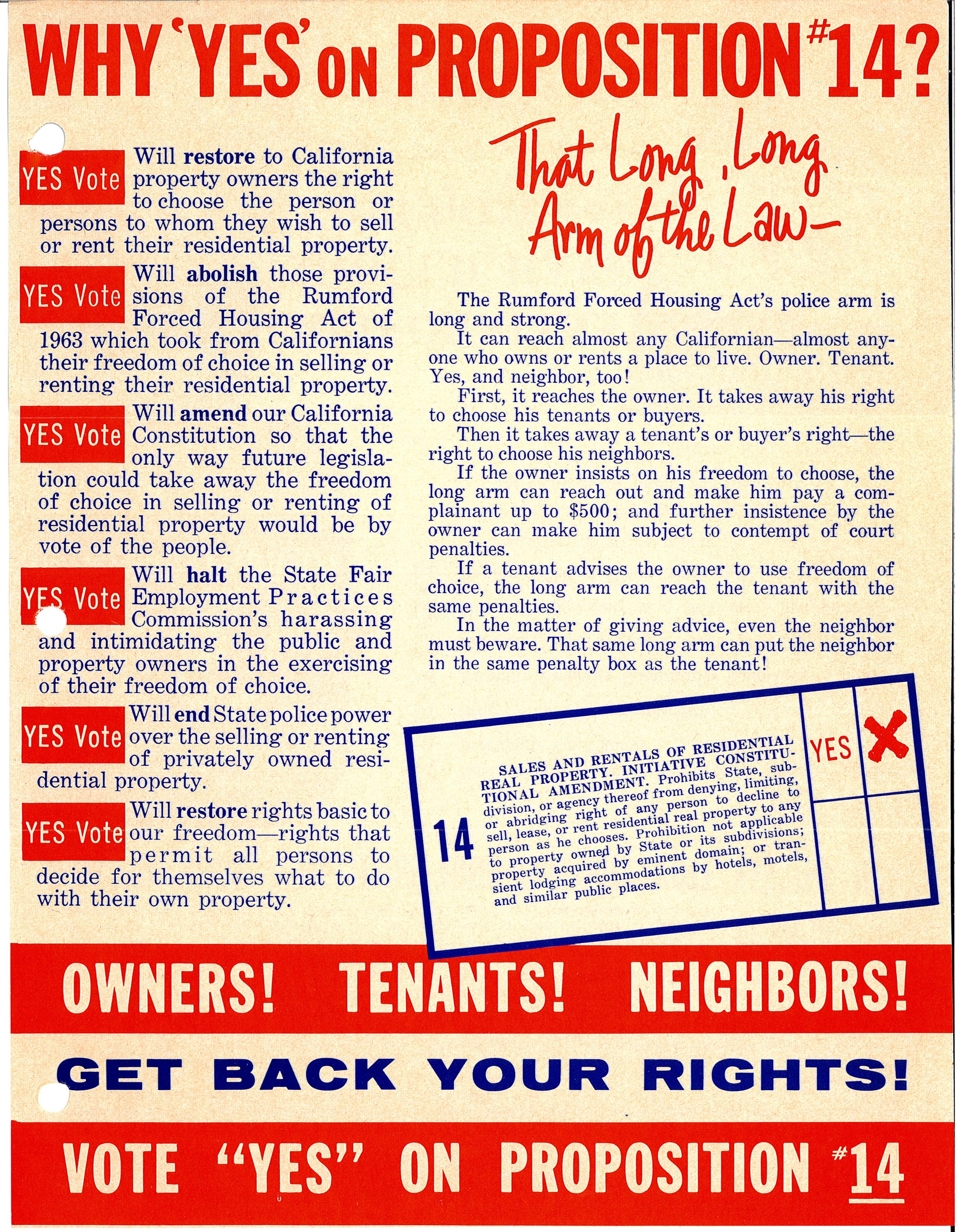

Much has been written about the federal government’s role in the New Deal Era of identifying majority-white areas as sound and profitable real estate investments and heavily subsidizing them through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) while simultaneously depriving majority-Black neighborhoods of similar assistance through a practice known as redlining.7 The mortgage industry writ large has been responsible for perpetuating that discrimination in underwriting loans on a disparate basis favoring white people.8 While racialized housing inequality in the Bay Area is part of this national dialectic, it is not solely a function of factors outside of local control. In fact, many of the tactics of exclusion and dispossession were deeply localized in practice, driven by local actors such as homeowners’ associations and neighborhood groups, real estate agents and developers operating within the regional housing market, and institutions, such as local governments and public agencies, which collectively shape local policies and markets. This report examines the history of how these local tactics of exclusion and dispossession worked to establish and uphold a racial hierarchy in Bay Area housing prior to the establishment of the California Fair Housing Act in 1966 and the federal Fair Housing Act in 1968.9 By prohibiting discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing, these acts changed the legal terrain within which exclusionary tactics operated, thus requiring them to take new forms. But by this point, racially inequitable systems had already rooted exclusion in place.

In this report, we do not aim to expose a definite causal relationship between the tactics we describe and socioeconomic outcomes, nor indict certain jurisdictions over others. Racial residential exclusion operated systemically and regionally, even while local actors have made land use and housing decisions independently. We also recognize that this research does not cover the region’s more recent history or all the significant tactics or events related to the topic. For instance, we did not find local evidence of contract selling,10 an exploitative housing arrangement common in some African American communities in other regions. With these limits, the purpose of this report is to highlight policies and actions that historically perpetuated racial inequality in housing in order to further a conversation about how to achieve more inclusive and equitable communities.

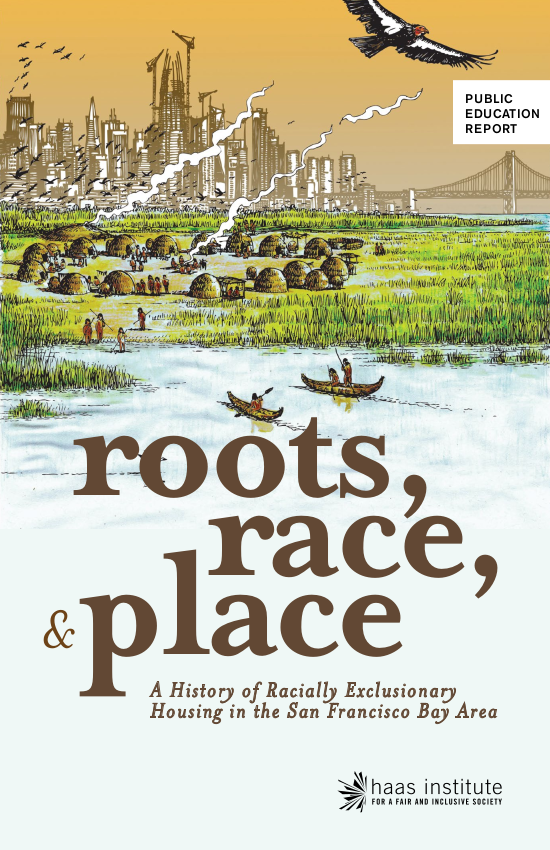

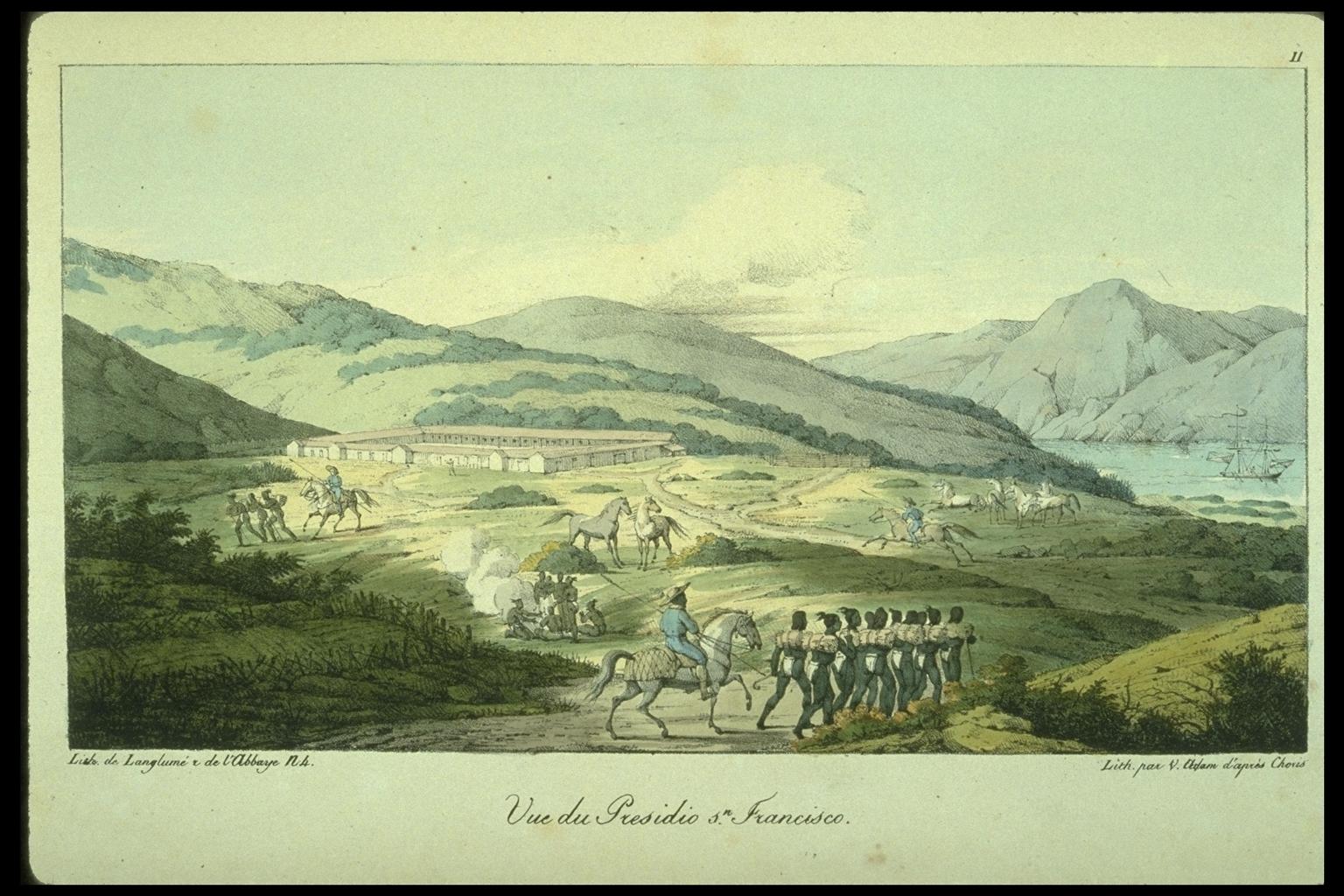

Timeline

Key Findings

Racial residential segregation in the Bay Area is not natural or simply a matter of individual preferences and actions. Today’s patterns are partially the result of a wide range of coordinated tactics used to perpetuate racial exclusion prior to the enactment of state and federal fair housing legislation. These exclusionary tactics can be distilled into the following types: state violence and dispossession, extrajudicial violence, exclusionary zoning, racially restrictive covenants and homeowner association bylaws, racialized public housing, urban renewal, racial steering and blockbusting, and municipal fragmentation and white flight.

Exclusionary practices have persisted and evolved as the legal terrain has shifted, finding new approaches when court challenges have invalidated previous tactics. The historical trajectory has been that as overtly racial measures became illegal, ones that have an implicit exclusionary effect have become more common. Yet there are early examples of “colorblind” policies that had racialized effects, such as San Francisco’s ordinance to prohibit laundries in white neighborhoods in the 1880s. Over 150 Chinese owners were prosecuted for violating the ordinance, while the city did not enforce the law against non-Chinese owners.11 We find that across eras, multiple tactics overlapped to simultaneously advance racial exclusion. Rather than a chronological succession of one tactic after another, some endured over multiple eras, and the overlap of multiple tactics contributed to their effectiveness. The timeline in this section shows when different tactics were employed and how they operated concurrently within time periods.

Violence and threats of violence are the longest-standing tactic used to enforce racial boundaries and dispossess people of housing and land. The initial colonization of the Bay Area was carried out through Spanish military expeditions and Catholic missions that used violence to coerce thousands of Native Americans to leave their homes and land. Later waves of violence against Native Americans were carried out by militias during the gold rush era and sanctioned by the State of California.12 Mob violence and arson were used to remove Chinese Americans from their Bay Area neighborhoods in the late 1880s.13 Anti-Black violence and threats were carried out by homeowners,14 the police,15 and the Ku Klux Klan16 with impunity as courts and prosecutors looked the other way.

Other exclusionary tactics were more subtle and not expressed in overtly racial terms. A set of social values and expectations, not always consciously tied to race in the minds of most residents, were instrumental in rationalizing practices bent on creating racialized spaces.17 These included low-density development patterns, consumer preferences for suburban neighborhoods and low tax rates, and a belief that neighborhoods without apartments, low-income residents, or people of color would successfully maintain high property values and/or appreciate the most over time.

Local laws that perpetuated racial exclusion were often the result of coordinated mobilization by actors within both the public and private sectors, which blurred the lines between public and private action. Throughout the region’s history, the interests of white property owners, government officials, and developers aligned over the protection of property values and accumulation of wealth based on racial exclusion. In many cases, their interests were one and the same. The South San Francisco city manager who facilitated the public vote against the Shengs was a Southwood homeowner himself. Founding board members of the public housing authorities in Richmond and Oakland previously held leadership positions in state and local apartment owner associations.18 The chair of the Berkeley Civic Art Commission who spearheaded the creation of the city’s original zoning ordinance in 1916 was also the president of northern California’s largest real estate brokerage and development corporation, which built numerous racially restricted subdivisions in Berkeley and San Francisco.19

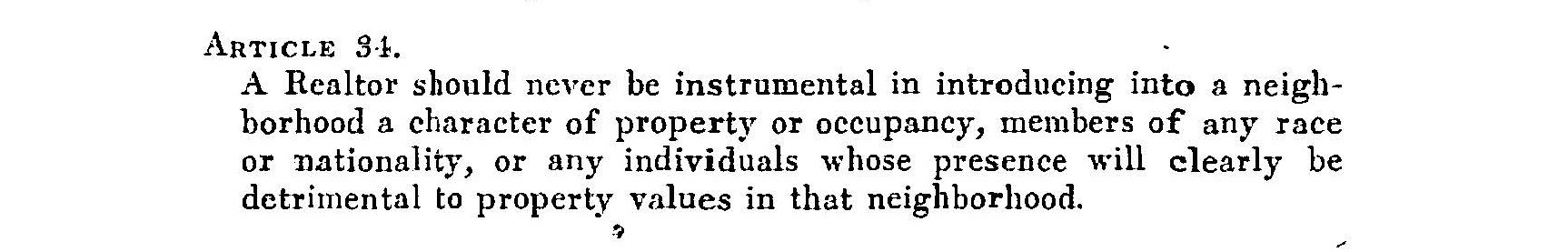

Many exclusionary housing policies now common across the United States originated in the Bay Area. San Francisco was among the first to use zoning to exclude specific racial groups with policies that were used to both explicitly (the 1890 Bingham Ordinance20 ) and implicitly (the 1870 Cubic Air Ordinance21 and 1880 Laundry Ordinance22 ) criminalize the city’s Chinese population. Berkeley’s 1916 comprehensive zoning ordinance that established exclusive single-family residential zones, celebrated by California Real Estate magazine for its “protection against invasion of Negroes and Asiatics,”23 pushed the limits of local zoning authority and became a standard in cities throughout the United States.24 In Oakland, after local developers, real estate agents, and landlords defeated a major public housing plan, their organization spearheaded the statewide ballot proposition that would establish Article 34 in the California Constitution, creating a major barrier to public and affordable housing across the state for decades thereafter.25

The Origins of Exclusion: State Violence and Dispossession

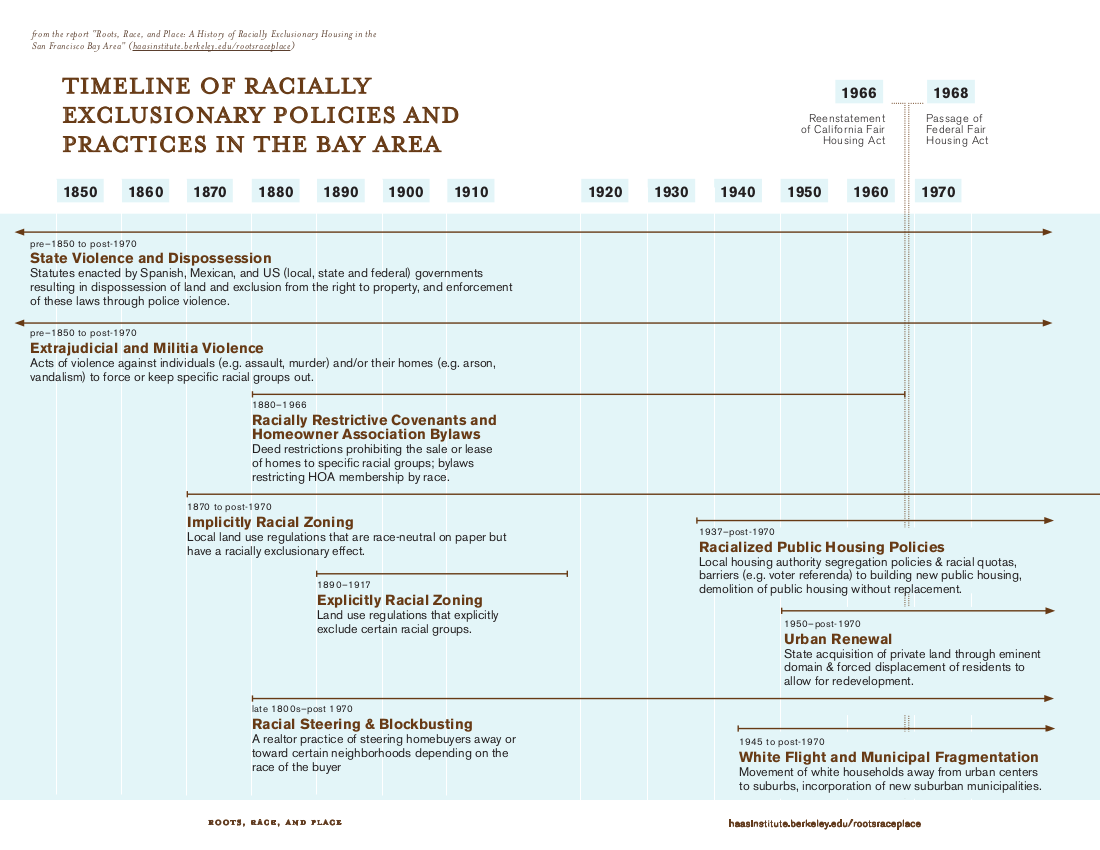

Racial exclusion in housing is a systemic process fundamentally tied to the control of land and the power to decide who is able to call a place home. The earliest forms of racial exclusion in the Bay Area were the violent dispossession of Native Americans’ land and concentration of ownership of land by Spanish, Mexican, and early US settlers and governments. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish soldiers and missionaries in 1769, an estimated 15,000 Native people lived in the Bay Area, comprising several tribes and dozens of communities.26 People had been living in the Bay Area up to or exceeding 10,000 years.27 Historian Benjamin Madley describes early California as “a thriving, staggeringly diverse place,” with “dense webs of local and regional cultural exchange.”28 Indigenous groups including the Ohlone (Costanoan), Coast Miwok, Wappo, Patwin, and Pomo inhabited the land that is now the nine-county Bay Area.29

Under the Spanish, Mexican, and US governments, the forced dispossession of land from Native peoples followed a logic of economic profit and racial hierarchy that became institutionalized through law, establishing a thread of racial capitalism, which carries through to the more contemporary forms of racial exclusion in housing detailed later in this report. For Spain, the establishment of 21 missions across California, including five in the Bay Area,30 was not just a “spiritual conquest” of Native Americans misunderstood as “gente sin razon” (people without reason). It was a strategic maneuver to preempt expansion by other colonizers and establish a protective buffer zone for its valuable silver mines in northern Mexico.31 The missions held Native people in forced labor and operated in concert with the Spanish military, which carried out violent attacks on Native communities.32

Legislating the Right to Property

This early history marks the creation of legal structures to uphold racial exclusion in California. Native Americans were forced into becoming legal wards of Spanish missionaries, under the physical control of the Spanish and unable to leave the mission without permission.33 This system, which was enforced by physical violence, made California Indians into second-class legal subjects and became the precedent for the two-tiered legal system later created by Mexican and US authorities.34 It also expelled inhabitants from the land, which was later sold or given to soldiers or other chosen beneficiaries.

The California Constitutional Convention laid the foundation for exclusion and dispossession under US law when delegates denied California Indians the right to vote.35 Following this decision and through a series of new laws, Madley explains, “legislators slowly denied California Indians membership in the body politic until they became landless noncitizens, with few legal rights and almost no legal control over their own bodies.”36

In the 1850s, under threat of violence, at least 119 California tribes signed treaties with US Special Commissioners in which they surrendered the vast majority of their land.37 In return, the Commissioners promised to provide for basic needs, protection and education, as well as designate land for 19 reservations. However, the US Senate rejected the treaties, and instead later authorized just five military reservations that comprised less than one-sixtieth of the acreage negotiated in the treaties, and provided no protection or any of the other promises made, leaving California’s Native populations extremely vulnerable to acts of violence by vigilantes and militias.38 Madley states, “Indians became, for many Anglo-Americans, nonhumans. This legal exclusion of California Indians from California society was a crucial enabler of mass murder.”39 Under US rule, California’s Native American population fell by nearly 90 percent, from 150,000 in 1846 to 16,277 in 1880.40 In the Bay Area, the Ohlone population plummeted to 2,000 by 1830, just 13 percent of the population 60 years prior. Today, people identifying as Native American or American Indian alone in the US Census living in the Bay Area number around 40,500.41

photo: Louis Choris’s “Vue du Presidio” (ca. 1815) depicts the early San Francisco coast with Spanish soldiers dominating the Ohlone people. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.42

After the US annexation of California through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the US government adopted the California Land Act of 1851, which governed the transition in property rights and created a commission that would investigate and determine the validity of all land titles from the Spanish and Mexican eras.43 Although the US pledged to protect the property rights of existing Mexican and indigenous landowners, incomplete records of ownership and imprecise surveys prevented many from successfully defending their property rights. As white Americans migrated to California during the gold rush era and began squatting on contested land, many former landowners were dispossessed.44 Historians Robert Heizer and Alan Almquist recount that by 1856, “most of the great Mexican estates in the northern half of California had been preempted by squatters or sold off by their owners to pay for the legal fees incurred in trying to have the titles validated.”45

photo: The Indigenous Bay Area, 1769. Map taken from Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas by Rebecca Solnit. Cartography: Ben Pease. Used with permission from University of California Press. © 2010 by The Regents of the University of California.

Also starting in this era, state and federal laws targeted Asian populations through the restriction of immigration (including the federal Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and Immigration Act of 1924) and immigrants’ rights to property. California adopted alien land laws in 1913 and 1920 with the purpose of driving Japanese farmers out of California agriculture and undermining the economic foundation of Japanese immigrant society.46 The 1913 law prohibited “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” which included all Asian immigrants, from purchasing agricultural land, restricted their leases to three years, and prohibited the sale or inheritance of land by one alien ineligible for citizenship to another.47 Japanese immigrant farmers were initially able to circumvent the law by purchasing land in the names of their US-born children or land companies until 1920, when California voters approved a more stringent law proposed by the legislature that prohibited aliens ineligible for citizenship from leasing agricultural land altogether, buying and selling stock in land companies that owned or leased agricultural land, and appointing themselves as guardians of minors who held land in their names.48 The 1920 Alien Land Law was later amended to also fully prohibit the usage, cultivation, and occupancy of agricultural land for beneficial purposes to restrict Japanese American farmers from engaging in contract cropping agreements with landowners.49

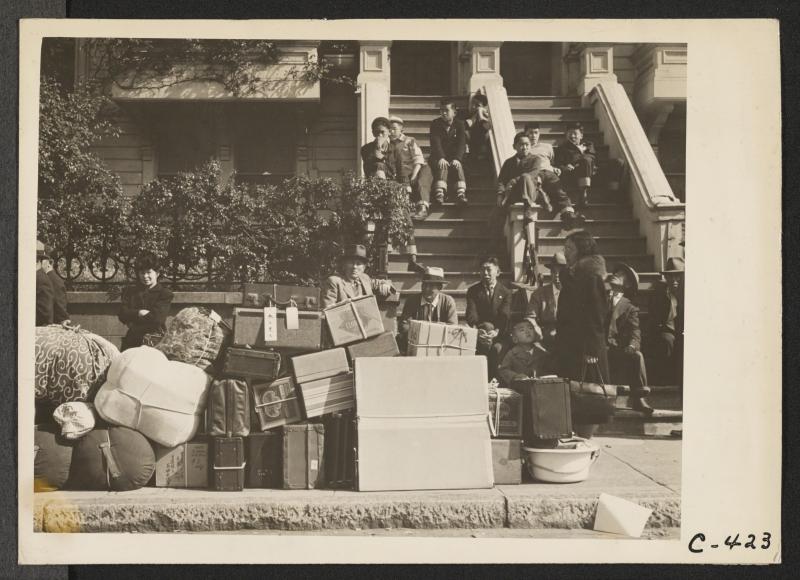

Before the alien land laws were struck down, forced internment of people of Japanese descent during World War II resulted in a massive loss of property and community in the Bay Area. Over the span of a few months, Japanese Americans were rounded up by US soldiers and local police, assisted by local officials and business leaders.50 In May 1942, the San Francisco Chronicle reported:

For the first time in 81 years, not a single Japanese is walking the streets of San Francisco. The last group, 274 of them, were moved yesterday to the Tanforan assembly center. Only a scant half dozen are left, all seriously ill in San Francisco hospitals. Last night Japanese town was empty. Its stores were vacant, its windows plastered with “To Lease” signs.51

All were required to sell or give away their belongings, and just weeks of notice provided insufficient time to get a fair price for farms, businesses, and homes. The economic loss has been estimated at $1–$3 billion nationally (not adjusted for inflation).52

During World War II, Californians aggressively sought to enforce the alien land laws to prevent interned Japanese Americans from returning.53 The laws remained in place until 1952, when they were overturned by a series of court cases (Oyama v. California, Fujii v. California, and Masaoka v. California) and furthermore made obsolete by the Immigration Act of 1952, which declared Japanese immigrants eligible for citizenship.54 They were officially repealed by a ballot proposition in 1956.55

Enforcing Exclusion

Local law enforcement officials played a key role in maintaining racial exclusion, as exemplified by police participation in rounding up Japanese Americans to be sent to internment camps in 1942. Racial exclusion occurred not only through the enforcement of exclusionary policies, but also through disparate enforcement that targeted people of color while maintaining impunity for white individuals, refusal to protect people of color from violence, and the direct use of violence to enforce the spatial boundaries of racial residential segregation. During and after World War II, local officials attributed rising crime and disorder, and particularly violent crime, to the growing population of migrant Black southerners.57 A 1943 Oakland Observer article captured the popular sentiment:

It is very possible that the trouble comes from immigrant Negroes from the South, who are held well under control in the South but, coming North, have found themselves thrilled with a new “freedom.”58

photo: Japanese Americans who were forced to evacuate their homes in San Francisco wait outside the Wartime Civil Control Administration Station on Bush Street, taking only what they can carry to the internment camps. By Dorothea Lange, April 29, 1942. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.56

Richmond officials took this explanation further, stating that in discovering the limits of this new freedom, the Black migrant “encounters many disappointments and frustrations, to which he may have an aggressive reaction.”59 This racialized rhetoric around crime waves and migrant immorality fueled local law-and-order campaigns throughout the 1940s. Campaigns of discriminatory policing served as a systematic form of racial control, according to historian Marilynn Johnson. Police regularly harassed Black men congregating in public spaces, threatening their arrest if they refused to disperse, and also arrested hundreds of people of color each year for mere “suspicion,” commonly when they were found in white neighborhoods.60 These arrests functioned to enforce the “unwritten rules and unmarked boundaries” of racial segregation.61

In response to mass arrests and police violence, the Oakland branch of the Civil Rights Congress sued the City of Oakland on behalf of several West Oakland residents. Advocates from the Bay Area Conference on Negro Rights stated that “legal lynchings in the form of frame-ups are multiplying,” and that “abuses of the civil rights of Negroes have reached a new level.”62 In the 1960s, the Black Panther Party called for an end to police violence and led a movement of “defending our black community from racist police oppression and brutality.”63 Historian Robert Self explains that the Oakland police department “responded to the Panthers with nothing short of guerrilla warfare—no less than three Black men were killed by Oakland police in the spring of 1968 alone.”64

While the extent of discriminatory law enforcement and police brutality throughout the Bay Area’s history is not fully documented, Black residents in other parts of the region reported patterns of discriminatory policing similar to that of Oakland. For example, in 1943 the Citizen newspaper reported improper conduct and police brutality by the Marin City Police Department and specifically four county deputy sheriffs paid by the Marin Housing Authority65 for using “gestapo-like tactics against Black workers and youth.”66

Beyond exerting control on public spaces, local law enforcement officials also policed segregation of private spaces. Historian Richard Rothstein describes one such instance in 1958, when Alfred Simmons, an African American teacher, rented a house in the Elmwood neighborhood of Berkeley from a white man, Gerald Cohn. Cohn had purchased the house with a mortgage insured by the FHA. Berkeley’s chief of police called upon the FBI to find out how Simmons managed to move into the all-white neighborhood. The FBI failed to prove that Cohn had always intended to rent the house to an African American instead of occupying it himself, but this still prompted the FHA to blacklist Cohn from ever obtaining another FHA-insured mortgage.67

Local police also perpetuated segregation by failing to protect people of color from violence, which had the effect of sanctioning it. Sociologist Chris Rhomberg notes that Piedmont police refused to provide protection for Sidney Dearing, the only Black homeowner in the city in 1926, and “when Dearing chose not to move, the city began condemnation proceedings against his property in order to force him out.”68 E. A. Daly, a Black newspaper publisher and real estate agent in Oakland recalled another case:

In 1923 Mr. Burt Powell . . . bought a house on Manila Avenue. We had to protect him for three or four weeks because the white people wanted to kill him because he moved in a white district. So we worked for him to watch over him for a period of twenty-four hours for about three months. After then things kind of quieted down. . . . There was another one on Genoa Street in the 5700 block. They put up a new house there and a Negro moved in. The white people tried to run this colored man out and we had to watch over him for about a month, day and night, to keep the white people from molesting him.69

Extrajudicial and Militia Violence

Extrajudicial violence including arson, assault, and lynching was a longstanding strategy through which racial exclusion, dispossession, and control were exerted. Police, prosecutors, courts, media outlets, and other parties looked the other way as individuals and groups carried out attacks on people of color who attempted to access housing (or in the case of Native Americans, maintain access to their homelands) and other resources. During the California gold rush in the 1850s, private militias organized violent campaigns against Native Americans across the state, resulting in over 100,000 killed, an estimated loss of two-thirds of the Native population.70

At times, this type of violence was formally endorsed by government officials, blurring the line between state violence and extrajudicial violence. As historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz recounts, “Although the U.S. Constitution formally instituted ‘militias’ as state-controlled bodies that were subsequently deployed to wage wars against Native Americans, the voluntary militias described in the Second Amendment entitled settlers, as individuals and families, to the right to combat Native Americans on their own.”71 Madley recounts the massacres of Native Americans in Napa and Sonoma counties in the 1850s, which resulted in zero convictions of the perpetrators. “As Indian killing spread and became increasingly common, California law enforcement officers took little action to protect Indians. This is unsurprising. State legislators had banned Indians from serving as jurors or testifying against whites in criminal cases...and leaders like Governor Burnett supported Indian-hunting ranger militias.”72

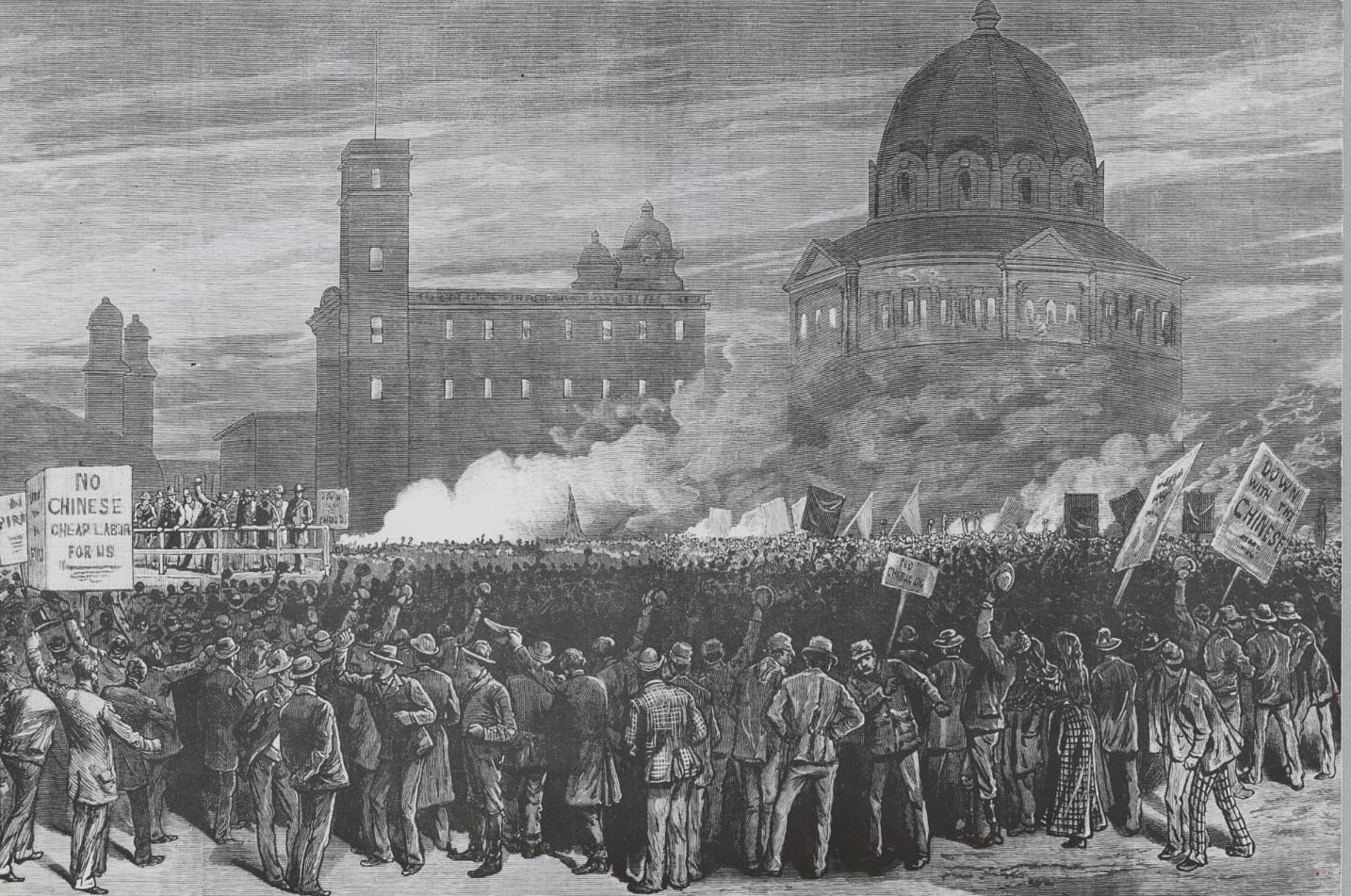

In the late-1800s, a wave of anti-Chinese violence occurred across the region, with several Chinese American communities forcibly removed and burned. San Pablo, San Jose, Antioch, and other towns in the Bay Area expelled Chinese American residents in 1886. Around the same time, arsonists set fire to the Chinatown neighborhoods in San Jose and other towns.73 Anti-Chinese violence and movements led by the Workingmen’s Party and Anti-Coolie Association,74 which was first established in San Francisco, gave rise to racialized zoning ordinances in the 1870s and 1880s, the California Anti-Coolie Act in 1862, and the federal Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.75

“Sundown towns” were a formal expression of the threat of violence to people of color existing in a town after dusk. From the 1890s to 1960s, thousands of towns across the country had designated themselves “white only,” and often had signs announcing that these areas were sundown towns, meaning African Americans, Mexican Americans, Chinese Americans, or other people of color were not allowed in town after the sun went down.77 Historian James Loewen keeps records of sundown towns, and lists Antioch, San Jose, and San Leandro as “surely” sundown towns, and considers it “probable” that Burlingame, Lafayette, Palo Alto, Mill Valley, Napa, Piedmont, and Ross were too.78 Loewen notes that in the 1940s, some realtors proposed designating the entire San Mateo peninsula a sundown area. An Atherton real estate agent “urged exclusive ‘white occupancy in the region,’” stating that the peninsula was “not a proper place” for “Negroes, Chinese, and other racial minorities.”79 The Pacific Citizen reported that other members of the realty board “felt the only way to handle the minority problem was to set aside acreage and subdivide it for minority groups with schools, business districts, etc.”80 Though the proposal for a sundown area was shelved, threats and violence largely kept people of color from moving in.

photo: An anti-Chinese riot takes place front of San Francisco City Hall in 1877, where the Main Library now stands. Line drawing by H.A. Rodgers. Courtesy of the California Historical Society.76

Several lynchings in the Bay Area were documented, although information on the full extent is incomplete. Historian Monroe Nathan Work (1866–1945), who meticulously recorded lynchings across the country as part of his work at the Tuskegee Institute, documented three acts of white supremacist lynching in the Bay Area between 1880 and 1920. These murders were carried out against a Black man in San Jose in 1892, a Mexican man in Los Gatos in 1883, and another Mexican man in Santa Rosa in 1920.81 Since the publishing of the Tuskegee Institute’s archives, multiple scholars have uncovered at least 10 other acts of lynching or white supremacist mob violence in the Bay Area between 1850 and 1920, which were carried out against five Mexican males, one Italian male, three Chilean males, and one Native American male.82 Lynching was far more common in the American South, a campaign of racial terror that contributed to the “Great Migration” of African Americans.83 Thousands of African American families migrated to the Bay Area in the 1940s and 1950s, coming from histories and experiences of racial violence in the southern communities they left behind.

For example, in 1943 after federal authorities ordered a shipbuilding corporation in Mobile, Alabama, to integrate and promote Black shipyard workers, a violent white riot against Black workers occurred, lasting several days. This spurred a group of workers to move to the Bay Area shipbuilding city of Richmond.84 In addition, as historian Marilynn Johnson explains, many Black migrants left because racial discrimination in the South barred them from economic opportunity. Despite labor shortages, many defense contractors refused to hire Black workers, while others refused to promote them or allow them to enroll in vocational training. “Growing frustration with local conditions, combined with promising reports from West Coast cities, encouraged many southern blacks to emigrate.”85

In the 1940s, high demand for workers in shipbuilding and other war-related industries drew the largest westward migration of African Americans, with nearly 125,000 settling in the Bay Area.86 The vast majority of Black migrants came from the South, with 65 percent from Louisiana, Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas.87 The Kaiser Shipbuilding Corporation, for instance, had an out-of-state recruitment program that aimed to secure 150 new workers per week for its yards in Richmond.88 Military supply centers, railroads, and docks also became major employment centers.89 The population growth of Richmond is telling of the growth of the African American population in the region during the time: in 1940 the US Census counted 270 African American residents and by 1950 there were 13,374.90 In the Bay Area as a whole, the Black population grew from 20,751 in 1940 to 149,809 in 1950.91 After the war, approximately 85 percent of Black migrants settled on the West Coast.92

But the newcomers found that they had not fully escaped racial violence by moving to the Bay Area, where white supremacist movements had taken root long before. The Ku Klux Klan had established a presence in the Bay Area during the 1920s, staging rallies, participating in public parades in their full regalia by the thousands, and carrying out cross burnings in places such as the hills of Richmond. Their freedom to do so was publicly endorsed in 1922 by that city’s main newspaper, the Richmond Independent.93

During and after World War II, widespread resistance to racial integration was expressed through intimidation and violence against Black families. Johnson explains the rise of anti-Black racism during this period:

By transforming the racial makeup of the Bay Area, the wartime influx of black workers also transformed the racial biases of local white residents. During the war years, blacks replaced Asians as the area’s largest racial minority. This shift was due not only to the growth of the black population but also to the removal and subsequent dispersion of Japanese-Americans. With the latter group confined in distant relocation centers and Chinese-Americans now allied in the anti-Japanese campaign, black migrants became the prime target of local bigotry. The antiblack racism that flourished during World War II would intensify in the postwar years, overshadowing the anti-Chinese sentiments that had historically dominated West Coast cities (Johnson, The Second Gold Rush, 55).

photo: In the 1920s, the Oakland Klan chapter had thousands of followers, and in 1925, 8,500 people participated in a Ku Klux Klan cross-burning ceremony inside the Oakland Auditorium (now known as the Kaiser Convention Center). Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.94

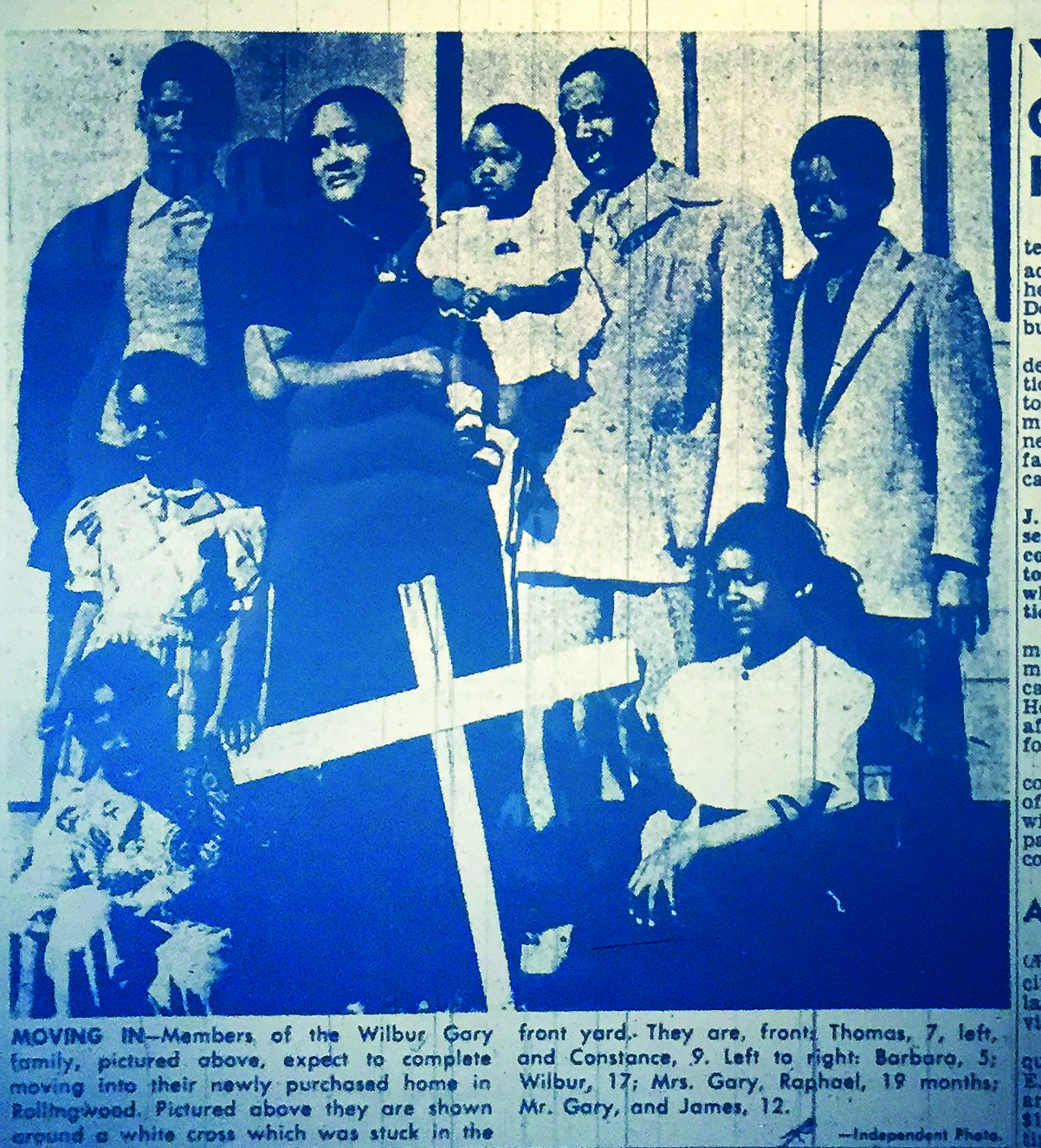

In 1952, Wilbur and Borece Gary and their seven children purchased a house in the Rollingwood subdivision in unincorporated San Pablo.95 Rollingwood was built during the war with federal loans, which required racial covenants that prohibited all 700 houses from being sold to African Americans like the Garys.96 These covenants were officially invalidated by the 1948 US Supreme Court decision, Shelley v. Kraemer, but segregattion remained in place until the Gary family moved in. News of the Gary family’s purchase prompted the Rollingwood Improvement Association to attempt to negotiate a buyout of the home, which the Garys refused.97 Upon moving, they became the target of death threats, violence, and intimidation by white residents. The office of their realtor Neitha Williams, who was also African American, was vandalized. In his open letter to the community, Wilbur Gary documented the placing of a Ku Klux Klan cross on their lawn and the gathering of a 400-person mob that stoned their home and shouted threats:

Sheriff’s deputies stood by and observed the rock throwing, they did not make a single arrest, nor did they order the rock throwers to stop. Since that night more rocks have been thrown and threats have been made, but still no arrests have been made and there has been no action by the authorities to put an end to this lawlessness.98

Similar cases of violence and intimidation, given impunity from local officials, have been documented in counties throughout the region. In Redwood City, the newly built home of John J. Walker, a Black war veteran, was burned down in 1946 after he received threats and demands to move out.99 African Americans who managed to purchase property in Sonoma County had to contend with the real possibility of racially motivated violence and vandalism. In the 1950s, the Santa Rosa weekend home of San Franciscan NAACP leader Jack Beavers was burned. Black and white neighbors alike agreed that the fire was likely a deliberate act “done to the family because of discrimination.”100

Intimidation also affected white individuals who were seen as facilitating integration. When the baseball player Willie Mays moved to San Francisco to play with the Giants in 1957, his family struggled to find an owner willing to sell to them. Mays and his wife Marghuerite placed a cash offer on a house in the city, prompting many neighbors to vehemently pressure the owner, Walter Gnesdiloff, to refuse the offer. Gnesdiloff’s employer stated that Gnesdiloff was “destroying himself and the neighborhood.” This opposition led Gnesdiloff to initially reject the offer: “I’m just a union working man...I [would] never get another job if I sold this house to that baseball player. I feel sorry for him, and if the neighbors say it would be okay, I’d do it.”101

photo: The Gary family stands on their front yard at 2821 Brook Way with a white cross, a symbol the Ku Klux Klan used to terrorize them from moving into the Rollingwood subdivision in San Pablo, which historically prohibited the selling of houses to African Americans. Published in the Richmond Independent, 1952.

With intervention from the San Francisco Council for Civic Unity and much public attention due to Mays’ fame, Gnesdiloff decided to sell. His realtor refused to take part in the transaction, claiming that his business would suffer as a result. Then one week after the Mays family moved into the house, the front window was smashed with a rock. Marghuerite Mays spoke out against the racism they encountered: “Down in Alabama where we come from, you know your place, and that’s something, at least. But up here it’s all a lot of camouflage. They grin in your face and then deceive you.” In response, the San Francisco Chronicle called out the hypocrisy of San Franciscans that “blunt the sharp edge of local indignation against citizens of the South who have been exciting little sympathy with their complaints that integration is a vexing problem.”102

As the region’s history of violence shows, extrajudicial violence often drove the adoption of new exclusionary policies, and it even furthered exclusionary tactics like racial covenants after courts ruled them unenforceable, solidifying this strategy as a dominant and enduring means of control and exclusion.

Exclusionary Zoning

Zoning encompasses the set of land use regulations local governments use to separate land into different sections, or zones, with specific rules governing the activities on the land within each zone.103 Today’s municipal zoning codes often include regulations related to building density and height, property lot sizes, placement of buildings on lots, and the uses of land allowable in particular areas of the jurisdiction.104 In the United States, they also typically regulate land by separating residential, commercial, and industrial uses from each other, and give residential zones the greatest protections from land uses that may cause nuisances or hazards to residents.105 Formally, zoning policies are typically justified by public health rationales, but in their design and effect they have often perpetuated racial exclusion. In some respects, Bay Area cities lead the country in creating zoning regulations motivated by racial exclusion.

Explicitly Racial Exclusionary Zoning

Many municipalities in the United States enacted outright racial zoning provisions in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries in order to separate white and nonwhite residents by law,106 and San Francisco was among the earliest. It became the first city to attempt to segregate explicitly on the basis of race by passing an ordinance in 1890 that sought to completely exclude Chinese residents from certain areas of the city. Known as the Bingham Ordinance, it would have given those residents 60 days to relocate to areas designated in the law or face a misdemeanor charge and up to six months in jail.107 However, a federal court quickly invalidated that ordinance.108

Over the following 27 years, numerous cities across the country adopted racial zoning and mapped and designated racial categories for each residential block. The US Supreme Court ruled explicit racial zoning unconstitutional in 1917,109 although some localities throughout the United States continued to enforce racial zoning after the court’s decision.110 Many segregationists abandoned racial zoning and began advocating for “comprehensive zoning,” while others turned to private deed restrictions to ensure continued segregation.111

Early Cases of Implicitly Racial Exclusionary Zoning

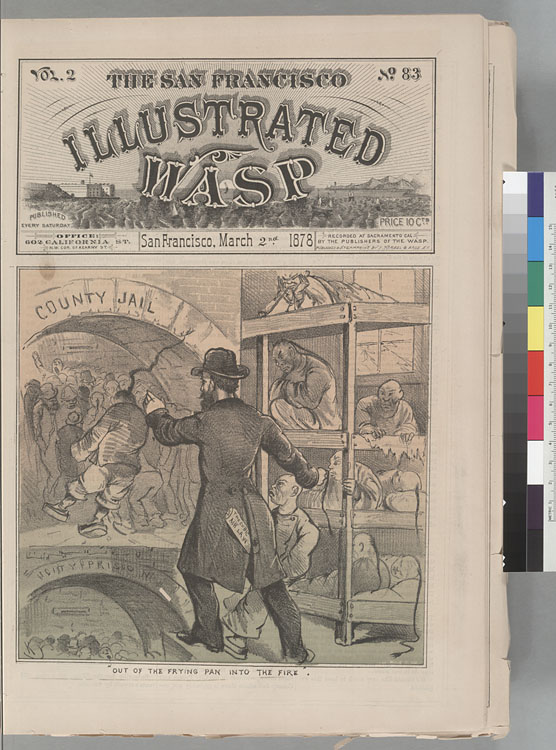

While establishing zoning districts that explicitly assign certain areas for one particular race or another was outlawed in 1917, other forms of zoning that do not mention race explicitly were widely used to achieve exclusionary effects based on race. Implicit exclusionary zoning in the Bay Area dates even further back than San Francisco’s explicitly racial Bingham Ordinance. In 1870, San Francisco established the Cubic Air Ordinance, which required 500 cubic feet of space for every person residing in a lodging house. Amid an era of anti-Chinese sentiment, the leadership of the Anti-Coolie Association brought forward the proposal, which was framed as a public health and safety measure. The ordinance led to the arrest and jailing of thousands of Chinese individuals in San Francisco, whose violations were considered misdemeanors punishable by a fine of up to $500 and/or up to three months in prison. A Chinese hotel owner successfully challenged the ordinance in the county court, but targeted arrests later continued in 1876 after the state enacted its own cubic air statute.112

photo: The March 2, 1878 cover of The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp depicts the jailing of Chinese lodging house residents following the adoption of the Cubic Air Ordinance. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.113

San Francisco also attempted to ban the establishment of laundries in all-white neighborhoods in 1880 by declaring it unlawful “for any person or persons to establish, maintain, or carry on a laundry, within the corporate limits of the city and county of San Francisco, without having first obtained the consent of the board of supervisors, except the same be located in a building constructed either of brick or stone.”114 While the ordinance did not explicitly mention race, its intent and impact were discriminatory because the large majority of laundries were operated by Chinese people and constructed of wood, and it gave city officials broad discretion to restrict where such laundries could be located. Environmental sociologist Dorceta Taylor notes while over 150 Chinese owners were prosecuted for violating the ordinance, the city did not enforce the law against non-Chinese owners. The US Supreme Court declared the ordinance unconstitutional in 1886 in Yick Wo v. Hopkins, ruling that the discriminatory administration of the statute was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.115

Comprehensive and Euclidean Zoning

Modern zoning has its roots in Berkeley, and racial exclusion and real estate profits were among the primary reasons for its development. Berkeley’s zoning district ordinance was passed in 1916 and created eight types of land use districts, but did not apply them to areas of the city until residents petitioned to have their neighborhood zoned. Some of the issues that motivated residents to zone their neighborhood were explicitly racial:

Early “zoning actions by the City Council in response to property owner petitions included one which required two Japanese laundries, one Chinese laundry, and a six-horse stable to vacate an older apartment area in the center of town, and another that created a restricted residence district in order to prevent a ‘negro dance hall’ from locating ‘on a prominent corner.’”116

The push for local government to set up zoning regulations was largely driven by real estate developers and was in part an effort to institutionalize the restrictions that had been enforced through private deed restrictions.117 The city council appointed Duncan McDuffie, a prominent Berkeley developer and leading proponent of zoning at the time, as chair of the Civic Art Commission, which spearheaded the passage of a zoning ordinance. According to McDuffie, “In Berkeley the value of protective restrictions has been amply demonstrated by their use in private residence tracts. The adoption of a district or zone system by Berkeley will give property outside of restricted sections that protection now enjoyed by a few districts alone and will prevent deterioration and assist in stabilizing values.”118 Several neighborhoods had been developed with five-year private deed restrictions that had expired, so the zoning would allow these restrictions to be renewed and institutionalized. As president of Mason-McDuffie, northern California’s largest real estate brokerage and development corporation at the time, which built numerous racially restricted subdivisions in Berkeley and San Francisco, McDuffie’s influence reached beyond the City of Berkeley. California realtors celebrated Berkeley’s racial exclusion, praising in the California Real Estate magazine in 1926 the city’s ability “to organize a district of some twenty blocks under the covenant plan as protection against invasion of Negroes and Asiatics.”119

According to planning scholar Sonia Hirt, Berkeley’s 1916 ordinance was also likely the first in the country to define a principal “Class I” zone exclusively for single-family houses, thus establishing the national trend that has come to distinguish US zoning.120 Leading advocates of zoning in Berkeley stated that “apartment houses are the bane of the owner of the single family dwelling,” and would “condemn the whole tract...of fine residences.”121 The same advocates also publicly voiced their explicitly racist motivations: “We [Californians] are ahead of most states [in adopting zoning]...thanks to the persistent proclivity of the heathen Chinese to clean our garments in our midst.”122

In the 1926 case Euclid v. Ambler, the Supreme Court ruled that zoning ordinances were generally valid so long as they were not arbitrary and unreasonable and had a “relation to the public health, safety, morals, or general welfare.”123 Furthermore, the ruling upheld and endorsed the concept of the exclusive single-family zone that Berkeley pioneered a decade earlier.124 Now constitutional, this type of zoning became the model for the rest of the country. Named after the court case involving the village of Euclid, Ohio, “Euclidean zoning” involves the separation of uses, special zones for single-family homes, setbacks, and height restrictions.

The widespread adoption of zoning coincided with an increase in immigration and, for the North and Midwest, migration of African Americans from the southern United States.125 Similarly, the Bay Area city of Milpitas, a largely white jurisdiction, used zoning to prevent Black workers from moving to the area after the Ford Motor Company moved its plant there from Richmond after World War II. Charles Abrams reported that when “the labor union attempted to construct housing for Black workers, the city rezoned the site for industrial use...Thereafter came a sudden strengthening of building regulations, followed by a hike of sewer connection costs to a ransom figure.”126 As demographic shifts occurred, the rhetoric used by planners in the early-twentieth century to justify the creation of separate residential zones for single-family homes and apartments tells a story of class and racial bias. Intermixing between these residences would “condemn” the single-family homes according to the architects of the Berkeley zoning plan. In this way, “zoning rules, like many of the other moral reforms of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, were designed to significantly reduce the likelihood that middle and upper-class children would come into contact with poor, immigrant, or black culture.”127

Berkeley’s zoning scheme and much of the Euclidean zoning that swept the country were early examples of implicitly racist policy design, evidenced in the publicly stated reasons for the policies, and their impact. In her national study of zoning and segregation, Trounstine finds that “cities that were early adopters of zoning ordinances grew to be 10 percent more segregated over the following fifty years than did cities that were not early adopters. The results also illustrate that zoning ordinances doubled the amount of renter segregation. In early adoption cities, property values would also become more unequal by 1970.”128

A postcard from ca. 1915 depicts a residence in the Elmwood district of Berkeley. Elmwood Park was the first Berkeley subdivision to be assigned the exclusive single-family residential zoning designation. Duncan McDuffie of the Mason McDuffie Company, which created the neighboring Claremont subdivision, advocated for exclusive single-family zoning in Elmwood out of concern that a lack of public zoning could lead to Claremont becoming surrounded by "incompatible" uses that would affect his subdivision's property values.

photo: A postcard from ca. 1915 depicts a residence in the Elmwood district of Berkeley. Elmwood Park was the first Berkeley subdivision to be assigned the exclusive single-family residential zoning designation. Duncan McDuffie of the Mason McDuffie Company, which created the neighboring Claremont subdivision, advocated for exclusive single-family zoning in Elmwood out of concern that a lack of public zoning could lead to Claremont becoming surrounded by "incompatible" uses that would affect his subdivision's property values. Courtesy of Berkeley Public Library.

The real estate industry’s advocacy for zoning was driven by tightly intertwined interests in generating profit and maintaining racially exclusive areas. Real estate developers, who had often developed large tracts of dozens or hundreds of homes, feared that the allowance of people of color would lower the sale prices of the homes, a concern that white homeowners also voiced. Historian David Freund illuminates the racial underpinnings of zoning:

Zoning’s original intent must be understood in the context of early twentieth-century racial politics, when enthusiasm for the new science of land-use economics converged with assumptions about racial, specifically eugenic, science. Most early zoning advocates believed in racial hierarchy, openly embraced racial exclusion, and saw zoning as a way to achieve it. But they formulated strategies and sketched out a language for justifying segregation that focused on practical, supposedly nonideological considerations.129

Trounstine states that “as zoning practices spread through the 1920s, emphasis on the enhancement of property values became the dominant argument.”130 The real estate industry’s involvement in the emerging field of urban planning nationally resulted in a “decisive (and quite rapid) shift in zoning’s focus, away from the broad concern with ensuring ‘best use.’”131 Then “almost universally, it was believed that the wrong sorts of people residing, or even working, in an area could negatively impact property values.”132 Furthermore, “African American residential mobility was always understood in negative terms, because it forced ever wider readjustments of property values in white neighborhoods.”133 As Robert Self aptly remarks, “Containment is not too strong a word for the industry’s desire to minimize these readjustments.”134 This enshrined a “theory of land-use economics [that] treated racial and class differentials, like other supposedly objective land use variables, as calculable.”135 The circular logic of this argument would prove self-fulfilling: white people feared the presence of people of color would lower their property values, so when people of color did move in, white people quickly sold, earning a lower price than they would otherwise. This logic also devalued homes owned by people of color, driving down overall neighborhood prices.

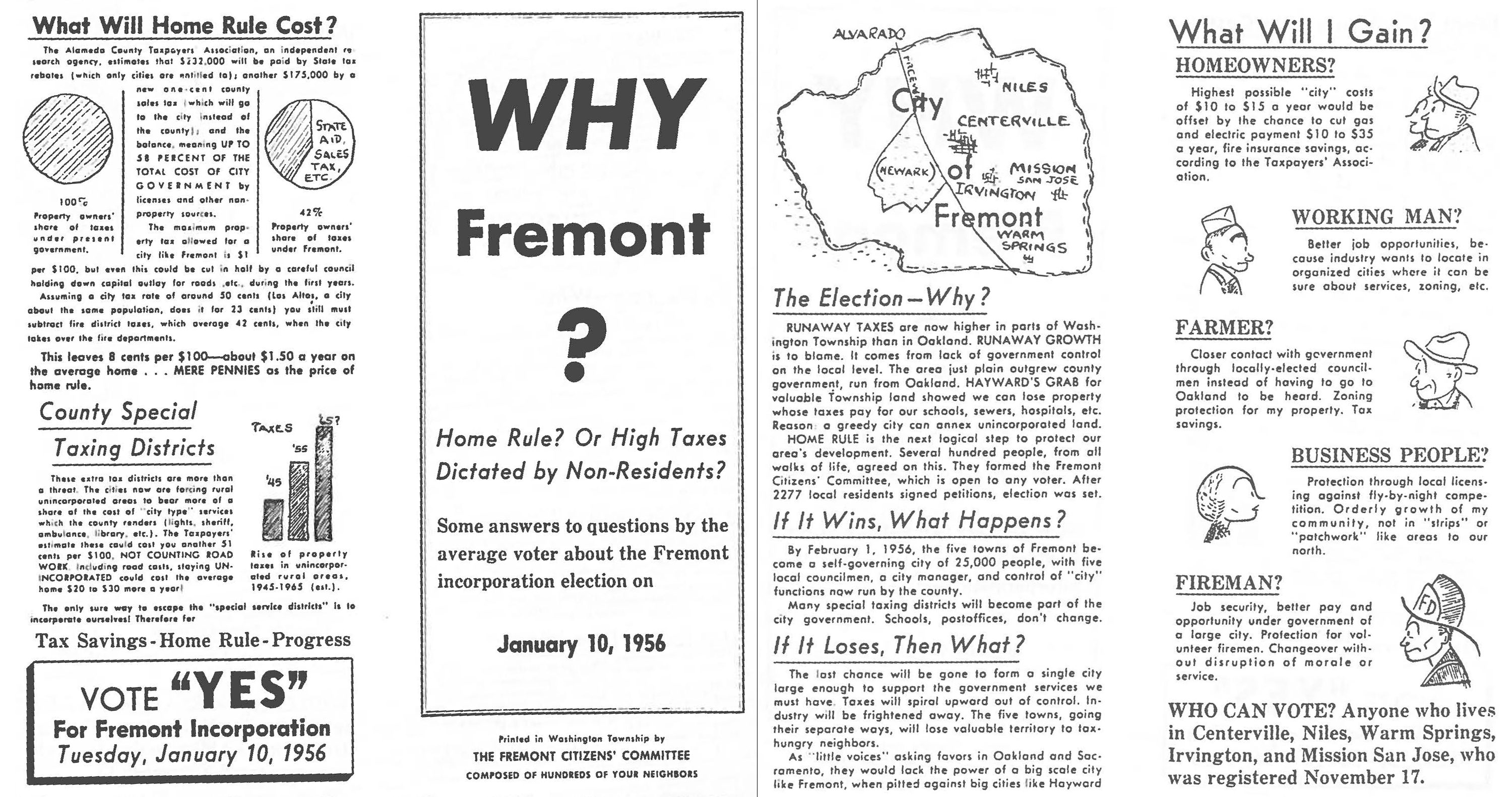

Incorporated municipalities also turned to exclusionary land use policies like large minimum lot sizes, growth boundaries, and caps on new units. For example, immediately after Atherton was incorporated in 1923, the town adopted a zoning ordinance imposing a one-acre minimum lot for housing.136 In the mid-1950s, more suburbs, typically seeking to prevent annexation, followed suit in adopting stringent land use regulations. Los Altos Hills, incorporating in 1956, enacted a one-acre minimum lot size and precluded multifamily housing in their zoning ordinance.137 The 1959 General Plan states the citizens’ intentions were to preserve the town’s “rural-residential” character and avoid “undue burdens” upon the town’s resources with population concentration.138

Racially Restrictive Covenants and Homeowner Association Bylaws

Throughout the late-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, white property owners and subdivision developers wrote clauses into their property deeds forbidding the resale and sometimes rental of such property to non-whites, particularly African Americans.139 This approach was endorsed by the federal government and the real estate industry at least through the 1940s, and in many cases was required by banks and other lending institutions.140

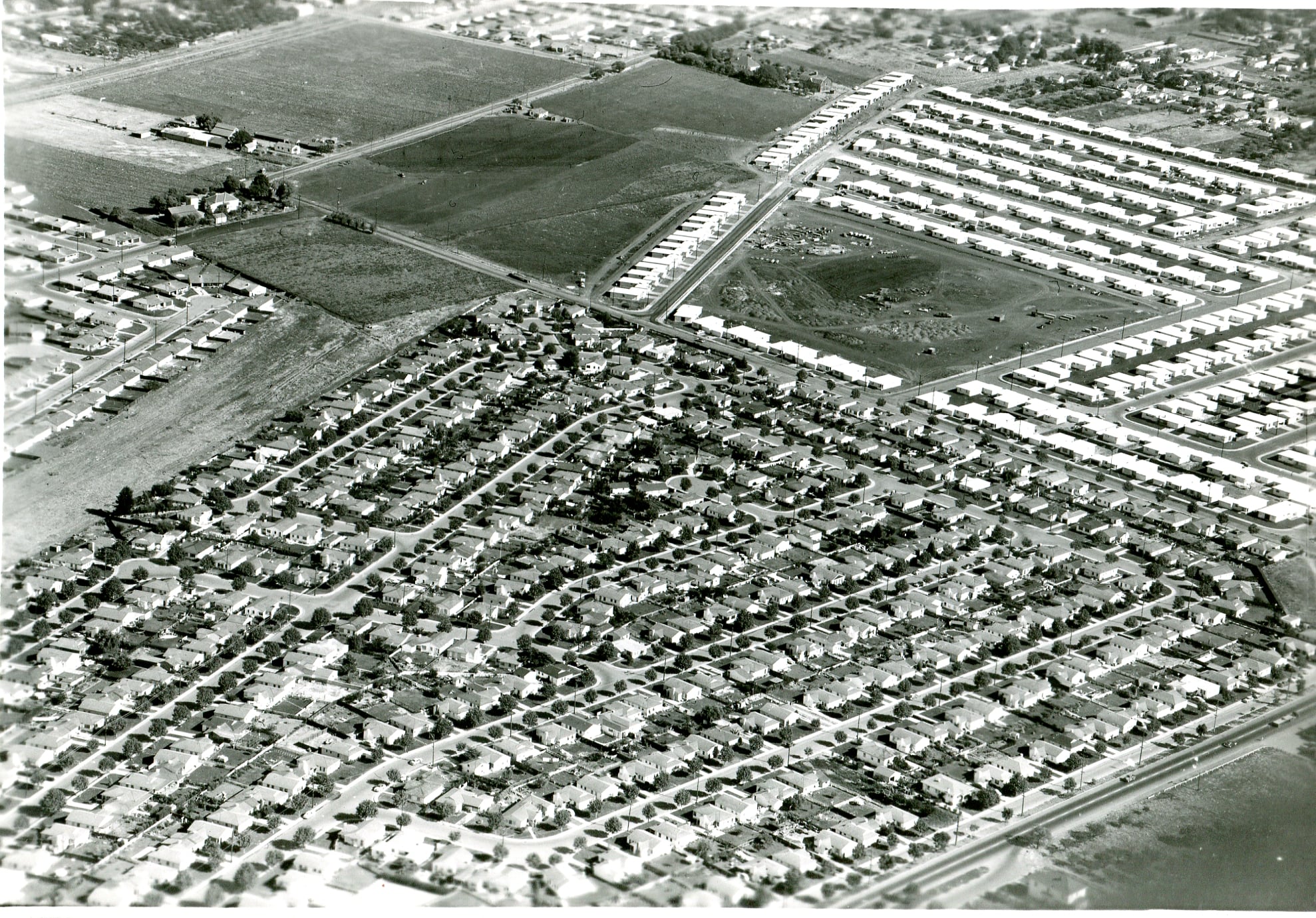

photo: An aerial view of San Lorenzo Village in 1950, which included nearly 1,500 single-family homes. Construction of the white-only subdivision began in 1944, in anticipation of the postwar increase in housing demand. Courtesy of the Hayward Area Historical Society Archives.

Racially restrictive covenants were common across the Bay Area. The first homes in the subdivision of Westlake in Daly City were sold in 1949 and included a racial covenant that covered all properties in the development. The FHA insured the development even though it had stated publicly that the agency would not insure developers who excluded African Americans from their subdivisions.143 Similarly, when developers broke ground on the unincorporated community of San Lorenzo in 1944, a covenant excluding all but white residents covered the entirety of the development. The San Lorenzo Village Homes Association enforced these restrictions.144 Discrimination by agreement continued even after the Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants were unenforceable in 1948. Civil rights attorney Loren Miller lamented in 1960 that “three decades of unconstitutional judicial enforcement of covenants had frozen them into business practices, public thinking, and public morality.”145 Furthermore, as historian George Lipsitz details, “people denied the opportunity to buy a home (and thus accumulate assets) because of an illegal restrictive covenant...had to bear the brunt of challenging it themselves. They had to initiate legal action and bear the complete cost and burden of seeking to have the law enforced.”146

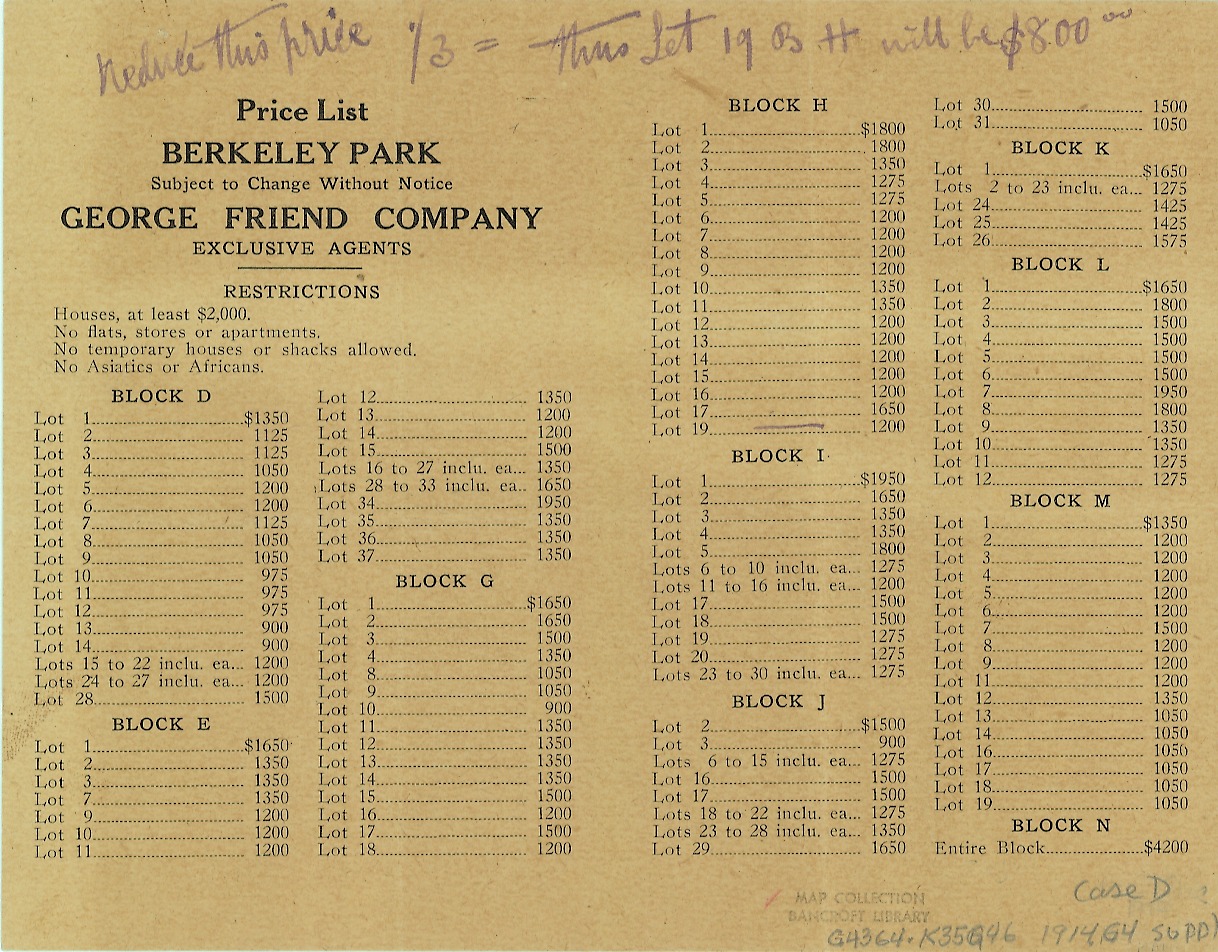

photo: The Price List for the Berkeley Park subdivision in Kensington includes a restriction against “Asiatics or Africans.” George Friend Company, ca. 1914. Courtesy of Earth Sciences and Map Library, University of California, Berkeley.142

In 1960, the Marin County Committee on Racial Discrimination reported that restrictive covenants were still in use, despite their illegality, in order to place social pressure on white families who did not wish to discriminate.147 According to Alexander Saxton, a retired history professor and a resident of Sausalito at that time, “Back then, Marin County was completely segregated. Housing segregation was strenuously enforced both by local banks and real estate people. White people could find new housing around the county, but Marin City was the only place open to black people. So that’s where they stayed.”148

After Shelley v. Kraemer, neighborhoods around the country, including in California, continued to bar African Americans and other racial minorities from purchasing property in their neighborhoods by creating community associations in which potential buyers would have to become members before purchasing property in the area. The white homeowners’ associations were often created by real estate developers.149 Because the bylaws of these associations restricted membership to whites only, they functioned to prevent African Americans from buying in those neighborhoods.150 Associations like these and remaining covenants, along with federal and state governments’ refusal to enforce compliance with Shelley v. Kraemer, kept many neighborhoods in the Bay Area entirely white through much of the twentieth century. For example, the City of San Leandro, whose population remained almost entirely white for decades after the Supreme Court ruling, maintained its racial exclusivity through homeowners’ associations that reportedly kept a “vigilante-like” watch on local real estate agents to ensure that none would show homes to African Americans and that the city government took no action to stop this intimidation.151 While unenforced, racially restrictive regulations remained within homeowner association bylaws in some instances as late as the 1990s and 2000s, such as Lakeside in San Francisco152 and Cuesta La Honda in San Mateo County.153

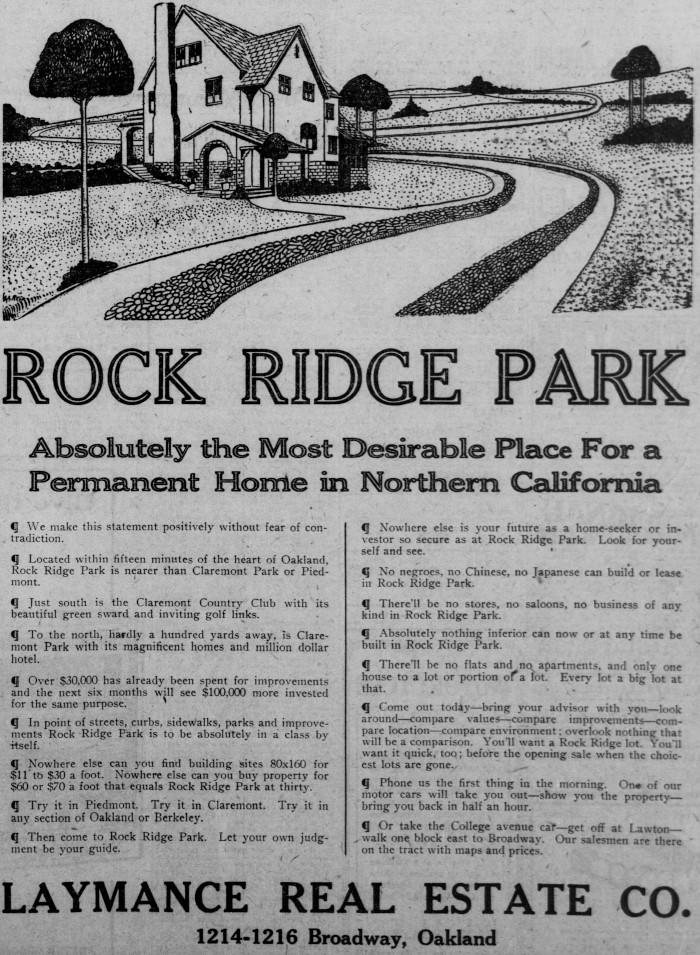

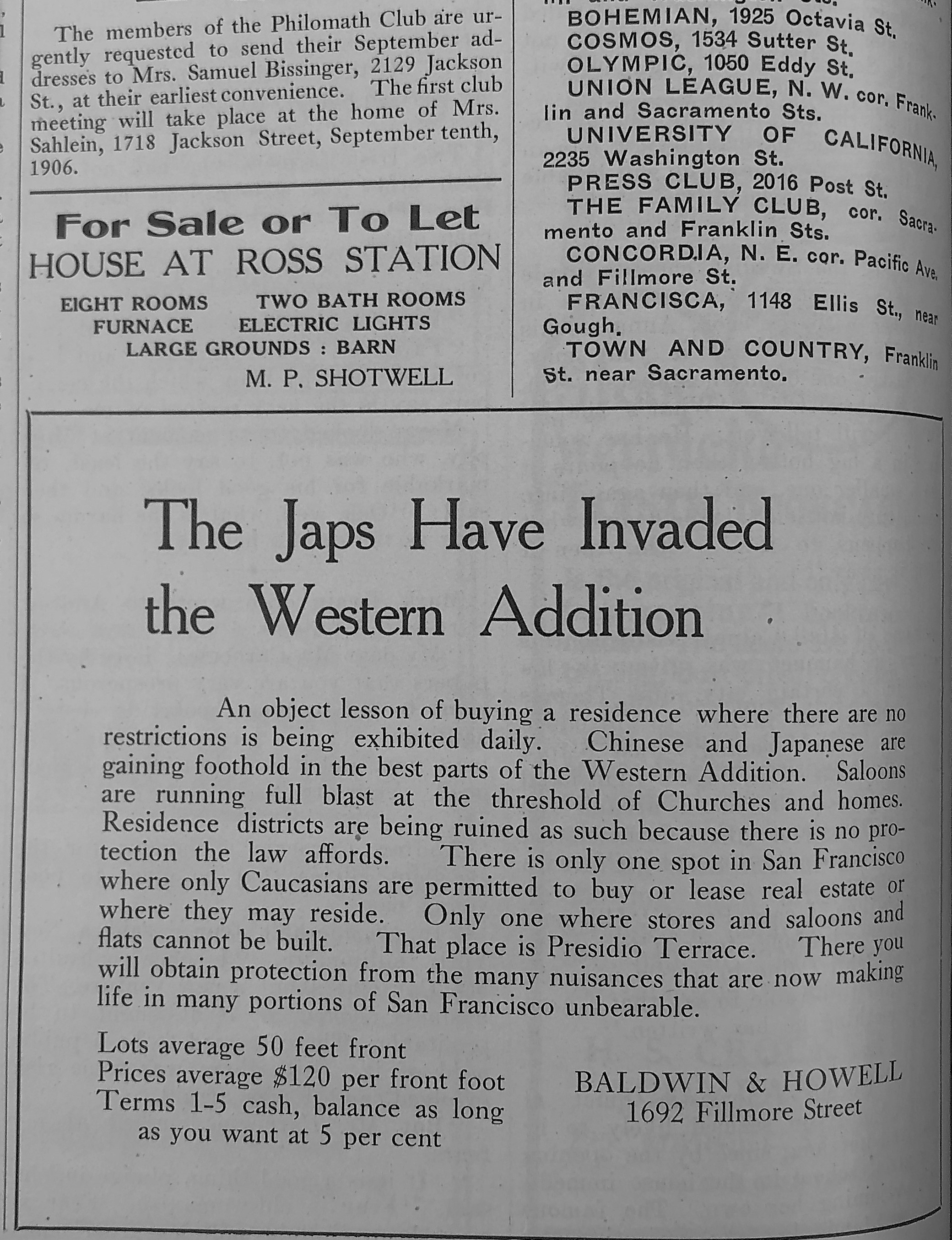

photos: Newspaper ads promoting racial covenants and racially exclusionary housing in Oakland and San Francisco. Left: A Laymance Real Estate Company advertisement for Rock Ridge Park in Oakland advertises that “no negroes, no Chinese, no Japanese” can build or lease in Rock Ridge Park. Published in San Francisco Call, October 13, 1906, Courtesy of California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside. Right: The Baldwin & Howell Real Estate Company markets Presidio Terrace as the “only one spot in San Francisco where only Caucasians are permitted to buy or lease real estate or where they may reside.” Published in The Argonaut, September 1, 1906. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California

Racialized Public Housing Policies

The history of public housing in the Bay Area demonstrates how public and private sector interests, alongside white homeowners, have operated in concert to perpetuate racial exclusion. The largest public housing expansion in the Bay Area occurred during World War II, as thousands migrated to the region for employment opportunities in war industries, resulting in a massive housing shortage and widespread homelessness. In response, the federal government created over 30,000 public housing units in the East Bay, which housed approximately 90,000 war workers and family members, in addition to thousands more units in other defense industry centers including San Francisco, Marin City, and Vallejo.154 These developments were initially constructed near shipyards and military installations in Richmond, Oakland, and Alameda, and later expanded into adjoining areas connected by public transportation.155 Since they were constructed as temporary homes exclusively for war workers, public housing effectively segregated the new war worker population into what historian Marilynn Johnson describes as a corridor of “migrant ghettos” next to federal facilities along the East Bay waterfront.156

Homeowner Opposition to Public Housing

Public housing faced vehement opposition during the war years in cities like Albany and Berkeley, which attempted to block public housing construction by refusing to create housing authorities. When the Federal Public Housing Authority proposed the construction of Codornices Village, a racially integrated 1,900 unit complex (which is now the location of UC Berkeley’s University Village) at the border of Albany and Berkeley, both city councils immediately opposed the project, as did the University of California, which owned a portion of the land targeted for development. Residents launched a petition drive against the proposal, expressing clear, though often coded, racial and class bias. Berkeley residents stated that the development was “not in keeping with a university city,” and the Albany City Council feared it would introduce “an undesirable element,” who would “force the integration of local schools and make Albany ‘like South Berkeley’,” which was a historically Black neighborhood.157 Codornices Village was ultimately built, but as a concession, the federal government allowed the project to become segregated toward the end of the war on an east-west basis, with Black residents forced to remain on the noiser, more polluted west side that was adjacent to the railroad tracks.158

Segregated Public Housing

With the exception of Marin City, wartime public housing in the Bay Area was officially segregated.159 Local housing authorities resolved not to “enforce the commingling of races,” and imposed “neighborhood pattern” policies through the 1950s.160 These policies gave preference to “families already residing in the area to conform with the social, economic and religious characteristics of the area” and meant that African Americans could only be placed in public housing where other African American families already resided.161 In Richmond, the housing authority director stated that the neighborhood pattern policy was necessary for “keeping social harmony or balance in the whole community.” Segregation in San Francisco’s public housing predated the war. During the early-1940s, the housing authority imposed a whites-only rule for its first three developments, which was designed to keep Chinese American residents out of public housing and confined to Chinatown.163

A 1952 federal investigation reported that San Francisco and Oakland were “possibly the only two Pacific Coast cities which continue segregation in their housing projects.”164 Even after the San Francisco Superior Court ruled in Banks v. the San Francisco Housing Authority that the San Francisco Housing Authority’s neighborhood pattern policy was a form of unlawful discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution as well as state and local laws, San Francisco Housing Authority officials refused to change the policy. An appeals court judge ruled that “neighborhood pattern is an arbitrary method of exclusion, a guarantee of inequality or treatment of eligible persons,” and the US Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal, finally leading to the integration of public housing in San Francisco in 1954.165

From the point of construction, white and Black public housing was not created equal. The vast majority of new public housing was intended to be temporary, and thus poorly constructed without much concern for design and safety.166 Many were built on landfill sites near railroads and industrial facilities along the waterfront, exposing residents to environmental and safety hazards.167 But in some all-white developments built farther inland, the public housing was constructed with sturdier materials and intended to be permanent.168

Additionally, due to “racial rationing” policies, fewer public housing units were available to Black families, despite the fact that racial discrimination in the private housing market afforded Black migrant families far fewer choices outside of public housing. Private housing options were limited to neighborhoods that were already home to Black residents before the war, and nearly all of the private sector solutions supported by the federal government, such as guaranteed loans for private housing construction and war guest programs that matched workers with homeowners that had spare rooms or other vacant accommodations, largely excluded nonwhite migrants.169

The local housing authorities, which controlled occupancy decisions and managed the public housing properties, used informal quota systems that limited access to Black applicants. The Federal Public Housing Administration encouraged the use of quotas to fairly distribute housing based on need, but as Johnson explains, the quotas reflected the white-Black ratio among war workers, rather than the ratio among public housing applicants, thus not accounting for the disproportionate need among Black migrants whose options outside of public housing were far more constrained.170 For example, the Richmond Housing Authority set a quota of four white households for every one Black household in 1943, and the inadequate supply of housing for Black families required many to double up or illegally sublet, which, if found by the housing authority, was grounds for eviction.171

The extreme shortage of housing for Black families thus led to overcrowding, and given the poor quality of construction, subsequent deterioration of the segregated public housing units. After the war ended, public housing waiting lists reached record length.172 As more white families were able to move out of public housing with the support of federal government programs, formerly race-restricted units were made available to Black families. Thousands more migrants arrived in the postwar era, and Black households became the majority of public housing tenants in Berkeley, Oakland, and Richmond. By 1946, more than half of the total Black population in the region lived in temporary war housing.173 These residents were essentially trapped, as racial discrimination continued to limit their housing options. Johnson notes that while Bay Area cities permitted over 75,000 residential units from 1949 to 1951, only 600 of these were open to Black homebuyers.174 She explains that their limited residential mobility restricted access to job opportunities in the postwar economy, especially as industry moved out to the suburbs, “literally freezing some families into unemployment.”175

Amid changing public housing demographics, regional economic shifts, and intermunicipal competition in the postwar era, local public debates turned toward urban redevelopment, “slum clearance,” and the removal of war housing as a necessity for progress. In 1949, Oakland officials stated that the war housing projects were the city’s “sorest blight problem,” “beyond the salvage point,” and “unsuitable for housing or any other use.” Richmond administrators echoed this sentiment, stating that the south side of the city where public housing was concentrated was becoming “a vast ugly slum, a reproach to the City and a constant source of trouble, conflict, and expense.”176

Real Estate Industry Influence over Public Housing

For some local housing authority officials, demolition of public housing had been the goal all along. Since their establishment, the local housing authorities that controlled and operated public housing in the East Bay were led by realtors, builders, and other private sector leaders.177 The Richmond Housing Authority was actually founded by the Chamber of Commerce in 1941 in an attempt to control pending federal efforts to construct public housing. The Oakland Housing Authority was established after the labor movement successfully pressured the Oakland City Council to create a housing authority and utilize available federal funding for public housing, but the council appointed a business-dominated board with representatives from the banking, insurance, and real estate sectors, including past presidents of the Alameda County Apartment House Owners Association and the California Rental Association.178 Their position was clear: “the business-dominated local housing authorities remained steadfastly opposed to permanent public housing that might undercut postwar private construction,” and were thus quick to allow the construction of temporary war housing, with the assumption that defense migrants would return to their home states and the temporary developments would all be demolished after the war.179

The campaign against public housing was led by the National Association of Real Estate Boards, which selected California as a test case for its national efforts.180 In Richmond, city officials abandoned plans to build over 4,000 permanent public housing units to pursue industrial growth and new private housing. In its demolition plans, the city prioritized developments primarily occupied by Black families. Without replacement housing and adequate relocation arrangements, over 700 Black families were displaced from their homes in 1952, only 16 percent of whom were able to find housing in the private market.181 Thousands of former public housing residents lost their homes by 1960. While many white families were able to move out to the suburbs with federally guaranteed loans, the southside of Richmond became predominantly Black by the late-1950s.

During the postwar housing shortage, the Oakland Housing Authority estimated that the city needed at least 23,000 new housing units. In 1949, the Oakland City Council narrowly voted to construct 3,000 units of public housing on areas designated as “blighted” near the city’s downtown using federal funds authorized by the National Housing Act of 1949. The proposal spurred a massive backlash led by the Apartment House Owners Association, the Associated Improvement Clubs, and the Associated Home Builders of Alameda County, which all came together with the support of the National Association of Real Estate Boards to form the Oakland Committee for Home Protection.182 The Oakland Post Enquirer reported that during one hearing on the proposal, a “throng of more than 500 [people] jammed every inch of the council chambers and another crowd of 500 demonstrating outside doors” to protest the plan forced the council to adjourn and postpone the hearing.183 The committee capitalized on anti-Communist sentiment and attacked public housing as “socialistic.”184 Following the city council vote, the Committee for Home Protection launched an aggressive, well-funded recall campaign to unseat three of the council members who supported the public housing proposal. One council member lost his seat in the recall election by just five votes, while the other two lost their seats in the following year’s regular election to candidates endorsed by the Committee for Home Protection. Without a majority in support for public housing, the new city council quietly rescinded the public housing plan.185

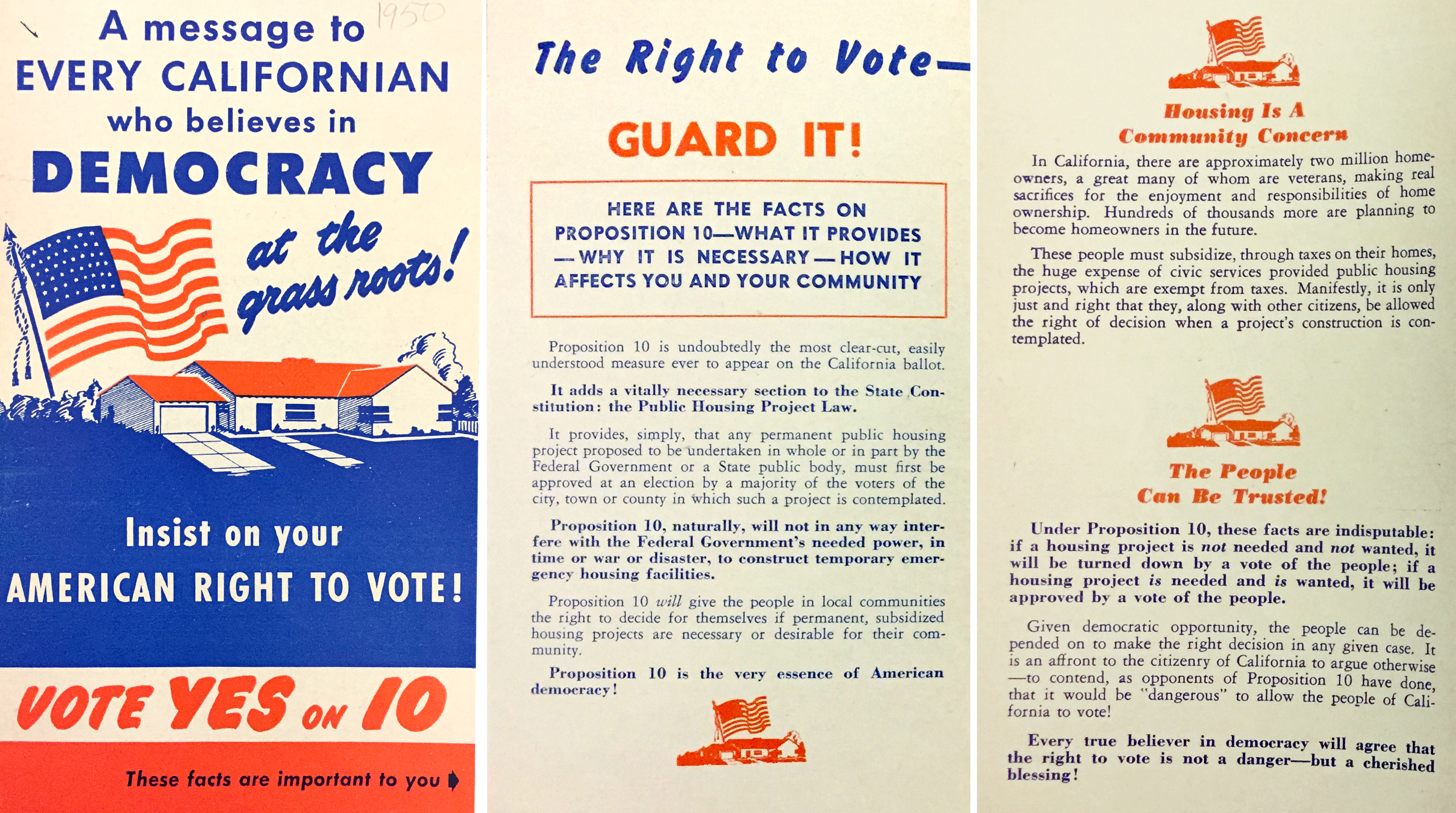

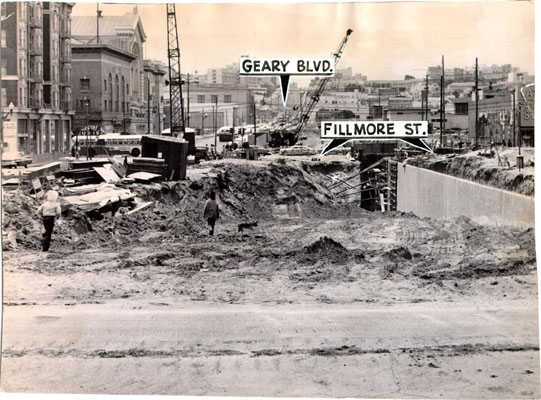

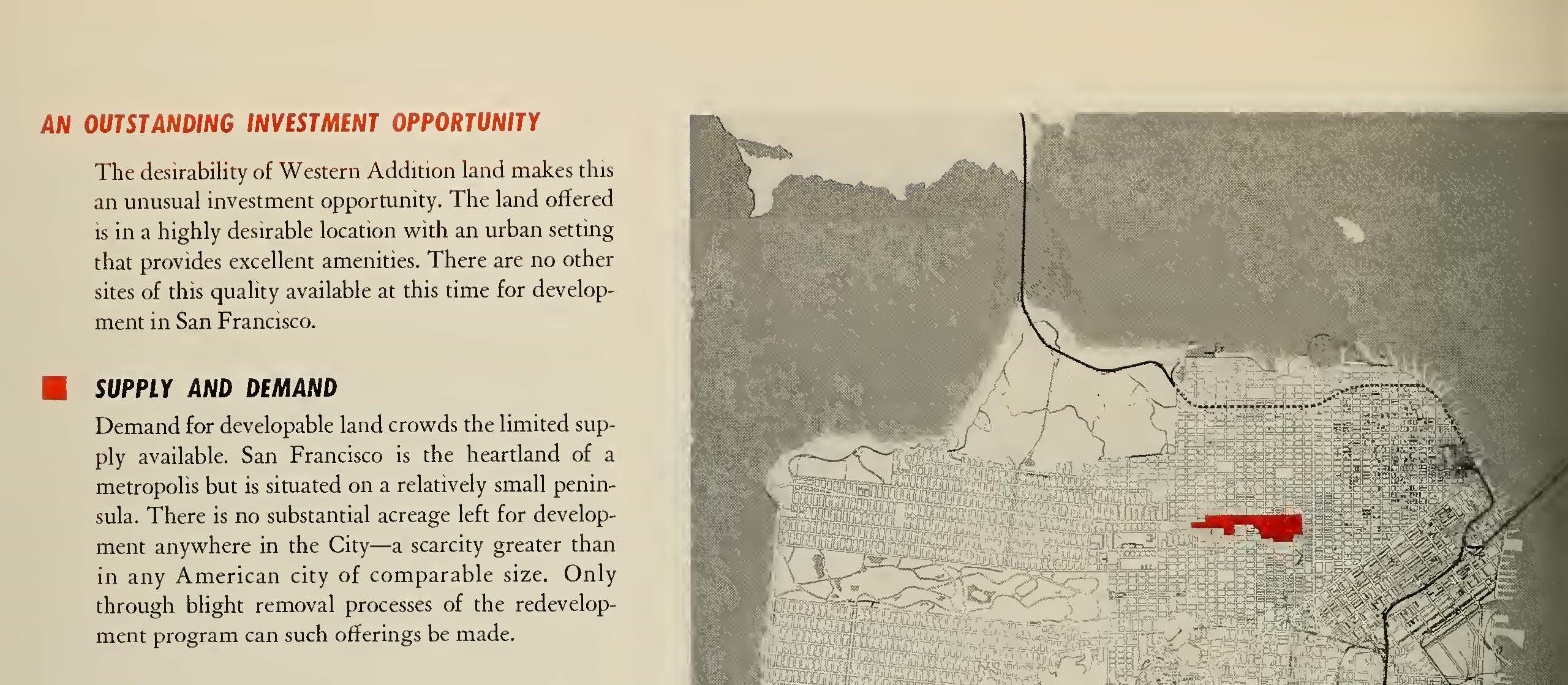

photo: The San Francisco-based Northern California Committee for Home Protection’s 1950 campaign for Proposition 10 framed its opposition to public housing as a matter of democracy. The back of the pamphlet reads, “Proposition 10 guarantees the right to vote where that right is most important of all—at the local, grass roots level. Proposition 10 strengthens democracy. Proposition 10 protects the rights of citizens in every community of California.” Courtesy of Liam Dillon, Los Angeles Times.

Creating New Barriers to Affordable Housing: Article 34’s Bay Area Roots

The defeat of the Oakland public housing proposal had statewide ramifications. Just one month after the recall election, the Oakland Committee for Home Protection played a key role in a statewide effort to amend the state constitution to mandate a local voter referendum for any federally or state-financed housing for “persons of low income.”186 This would create a massive political barrier to constructing new affordable or public housing. The Oakland Committee for Home Protection treasurer, John Hennessey, who was also the secretary of the Home Builders’ Council of California, organized the petition drive for the 1950 ballot measure (Proposition 10).187 Its passage in 1950 was codified as Article 34 of the state’s constitution. Courts and the California legislature have consistently narrowed its scope, and legislators are currently considering a measure to place the repeal of Article 34 on the state ballot,188 but the provision remains valid today.189