FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

BERKELEY, CA: Public schools in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico have been shuttered at a higher rate than any region in the U.S. over the last decade and a half, presenting a serious harm to the students and communities who rely on them, while failing to deliver the financial savings used to justify their closure, a new report shows.

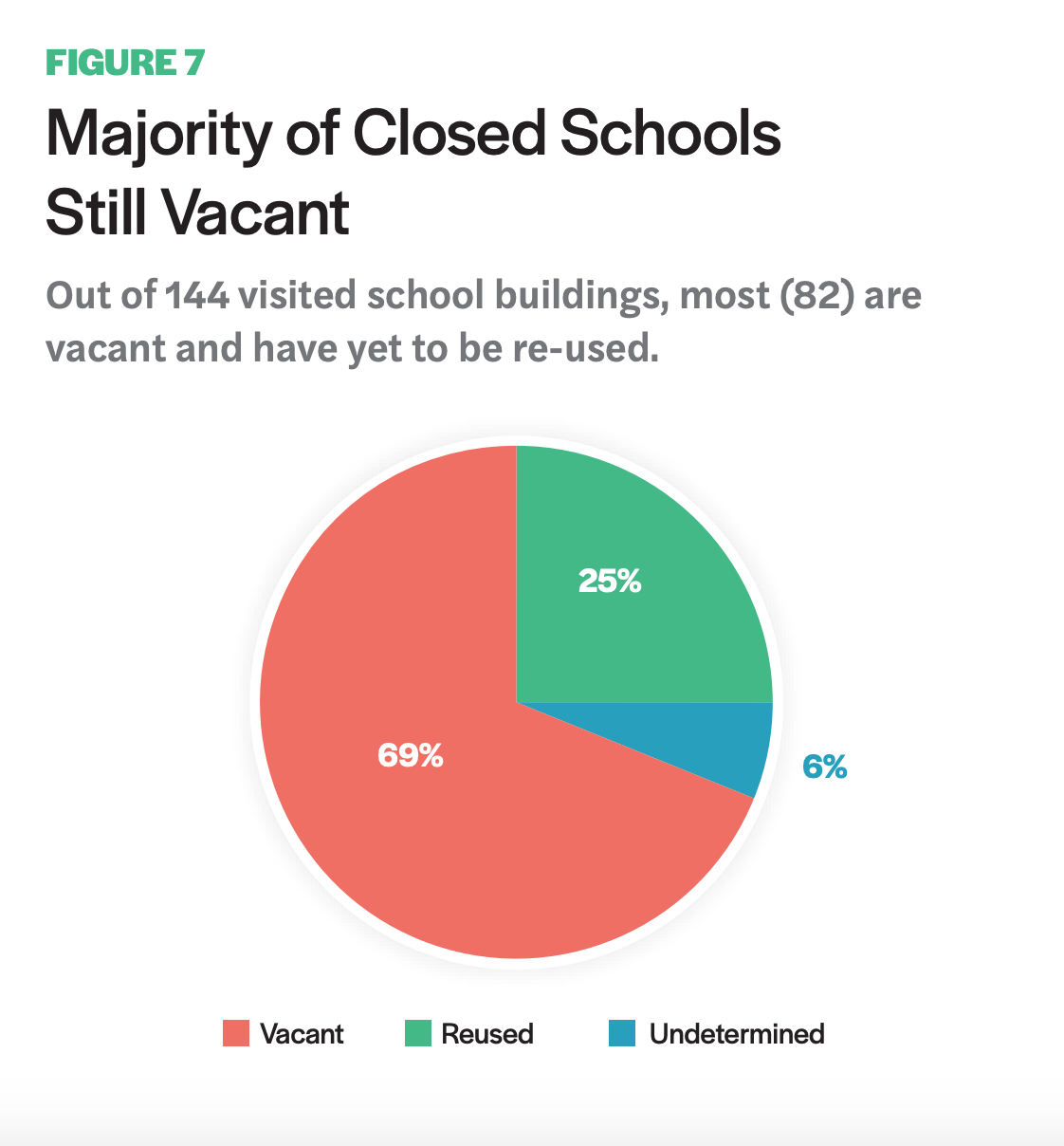

“Puerto Rico’s Public School Closures: Community Effects and Future Paths,” co-produced by UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute and San Juan-based Centro para la Reconstrucción del Hábitat, reveals that more than two-thirds of the closed schools still remain vacant, and of those that have been sold or rented, less than half are being used for the purposes described in their contract.

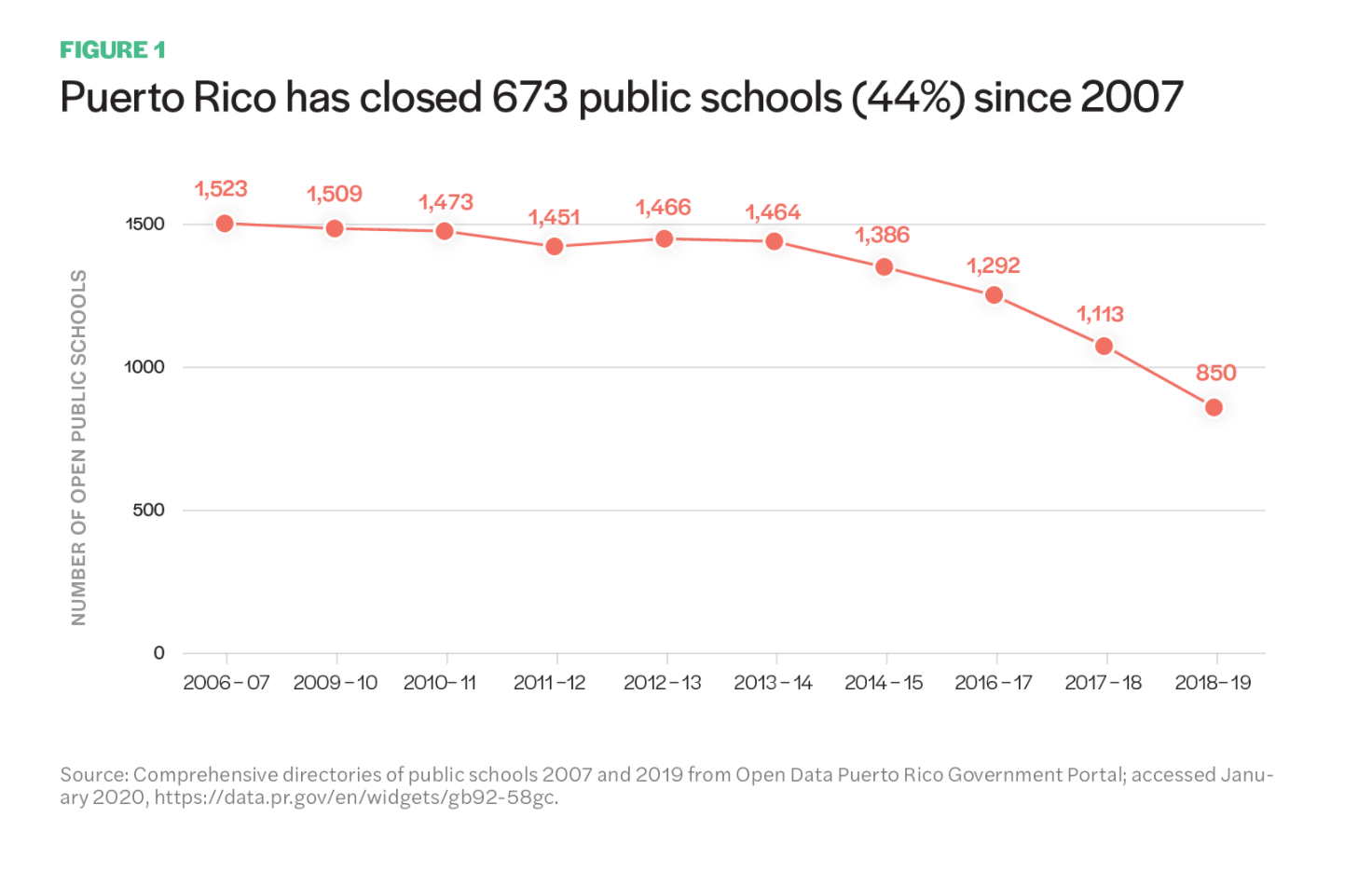

Since 2007, Puerto Rico’s Department of Education (DE) has closed 673 public schools, comprising 44 percent of the Commonwealth’s total. The dramatic decline accelerated following the government debt crisis which began in 2014 and the subsequent hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017. The DE announced in May 2018 that it would close 263 more schools, the report notes.

According to the report, the DE consistently cited declines in student population and the need for public revenue as the primary reasons for school closures. Proponents of free-market solutions pushed for privatization as a means to “reform” struggling schools and cut spending. The closures occurred with little public information or consultation with students, parents, or teachers, in a process described as unilateral and “antidemocratic.”

Ultimately, most school buildings were never repurposed after closing, and the financial benefits of the closures have been minuscule. Researchers conducted site visits to a randomly selected sample of 144 closed school buildings to find that 69 percent remained vacant.

Researchers also reviewed the 123 contracts related to the closed schools, finding that only 8 percent of the facilities had been sold and the rest rented. Of those rented, 80 percent were leased for the symbolic amount of $1. In total, sales and rental contracts produced less than $4.3 million in revenue, a meager amount compared to forecasted government savings.

Visits to the schools revealed that only 44 percent of those sold or rented were being used for the purpose described in their contract. Thus, the report argues that austerity measures were ineffective in saving funds, consequently undermining the “government’s obligation to its people” in favor of “its obligations on the debt flowing to investors.”

While the school closures generated meager financial gains, they dramatically disrupted the lives of students and their families. As the distance to one’s school increases, so do costs in travel time and expense, as well as disrupt access to and continuity in education. This is especially true in rural areas which have seen 65 percent of the total school closures since 2006.

But the impact of these cuts reaches beyond education because “schools play essential roles in the social, economic, and cultural life of a community,” the report notes. Puerto Rican schools double as emergency shelters, free clinics, food distribution locations, polling places, recreation centers, and community spaces.

“A closure can rupture intergenerational shared experiences, reduce parental and community involvement both at school and with their children’s education, and disperse the influence of the community in the governance of their school,” the authors write. Ultimately, “these impacts alienate communities and erode belonging.”

The authors warn that the school closures risk amplifying race and class inequalities, undermine government accountability, and potentially violate constitutional rights.

The report urges that measures be taken to keep “public assets in the public sphere, ensuring they serve public needs and remain accountable to the public.” The authors recommend the following:

- Stop the closure of public schools until a clear decision-making criterion and public process are established and publicly disclosed

- Incorporate the full range of community benefits provided by schools into the decision-making process

- If a school is to be closed, require that a reuse plan be created that is accountable to the community

- Launch an independent audit of the Department of Education to identify true savings or losses resulting from school closures

- Provide public access to data and records regarding school closures, leases, and sales so as to enable informed decision-making

- Remove the power to order school closings from the hands of the Financial Oversight and Management Board, and place it in the exclusive control of the Commonwealth and local communities served by those schools

- Conduct a new assessment of all public schools so the Department of Education can develop a more thorough plan moving forward

Puerto Rico has also developed an innovative model for public Montessori schools, which has grown to 45 schools serving 14,000 students in Puerto Rico, the largest and fastest-growing public Montessori project in the US. This is one example of “Transforming schools into high-quality, community-controlled public schools,” the report states, “a key strategy for healthy, resilient communities and equitable economic development.”

Click here to access "Puerto Rico’s Public School Closures: Community Effects and Future Paths."

Media contact:

Marc Abizeid

marcabizeid@berkeley.edu