Conditions at the Closed School Buildings

Physical Conditions and Current Use of Closed Schools

Communities across Puerto Rico are wrestling with what to do with over 650 closed school buildings. “There hasn’t been a study or plan for how to use the closed school buildings. They haven’t considered what the community needs and how to plan the reuse,” reported one leader. A Pew Charitable Trust study of closed school buildings in US states revealed that the longer schools are closed, the more difficult they are to repurpose; it also explained that school buildings in general are challenging to turn into any other use given their size and layout, including wide hallways and shared bathrooms.54

Most closed school buildings in Puerto Rico are still unused and have become blighted. In many cases, the closing of a school means more than the closing of a number of classrooms, a public library, or a cafeteria, but also the loss of theatres, playing fields, and other recreational and sport facilities. For example, out of the 673 schools that have closed since 2007, only 123 (18%) were formally contracted for reuse between 2014 and 2019. While some schools may have been leased or transferred prior to the public records being available beginning in 2014, the majority likely remain abandoned or without official use.

For the purpose of this report, researchers visited a random sample of 144 closed schools (out of 673 closed since 2007). The sample was selected from both official lists and press reports in order to assess their condition.55 Of these, 119 had been closed.56

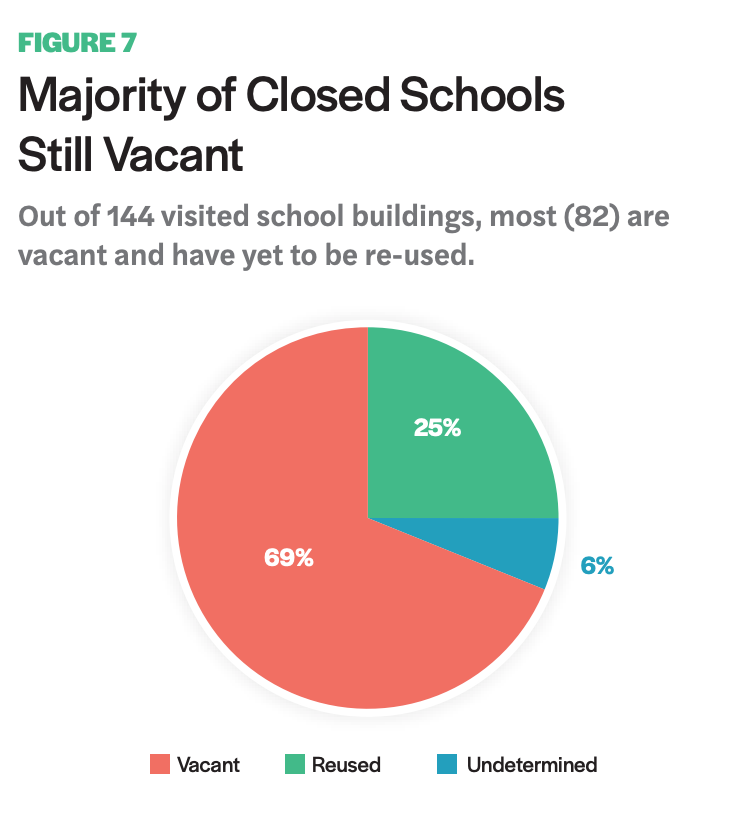

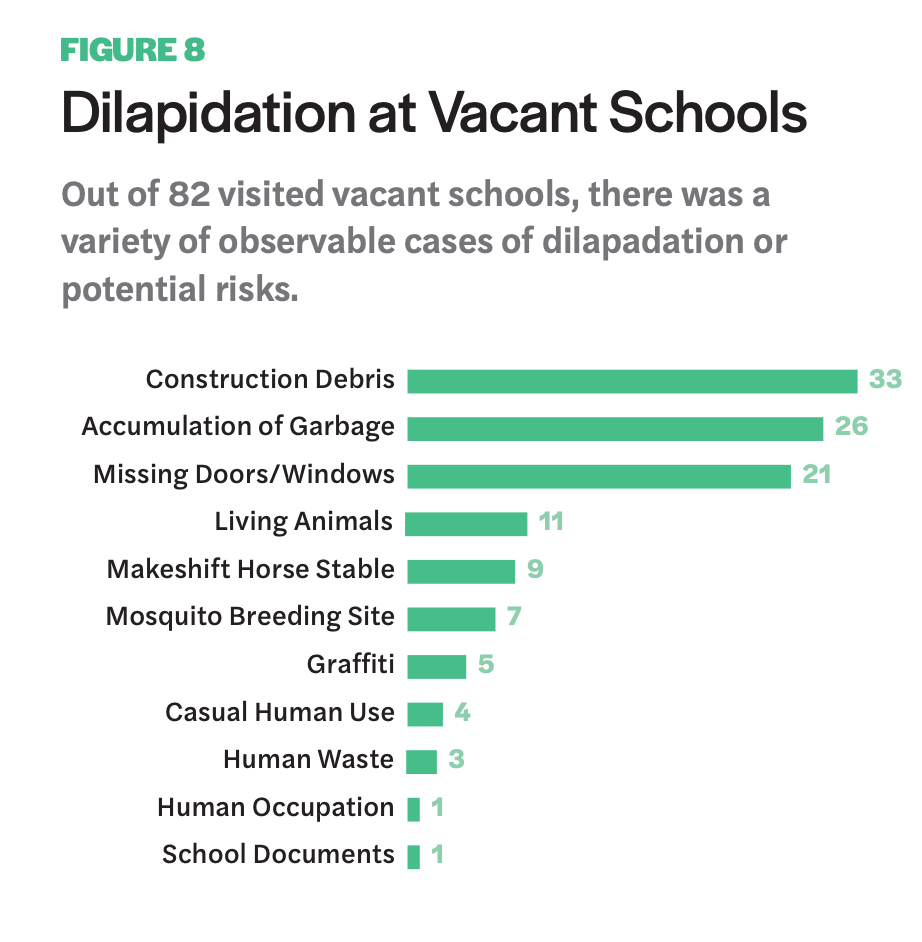

In total, only a quarter of the closed schools (30 schools) have been reused for some new purpose. On the other hand, 82 (69%) of the remaining schools lie vacant with many in a regressive state of abandonment. Researchers could not determine if 7 (6%) of the schools were in use or not (figure 7). Of those vacant, 59 (41%) of these closed school buildings suffer from at least some degree of dilapidation, damage, or safety risk. It is common to observe in these schools stolen or missing doors and windows (33 schools, 40%), the accumulation of trash (26 schools, 32%) and construction debris (21 schools, 26%), and graffiti (5 schools, 7%), as shown in Figure 8. Of all closed and vacant schools visited, 44 (53%) have green areas where vegetation has grown twelve inches or higher, with two (2%) being completely shrouded by vegetation.

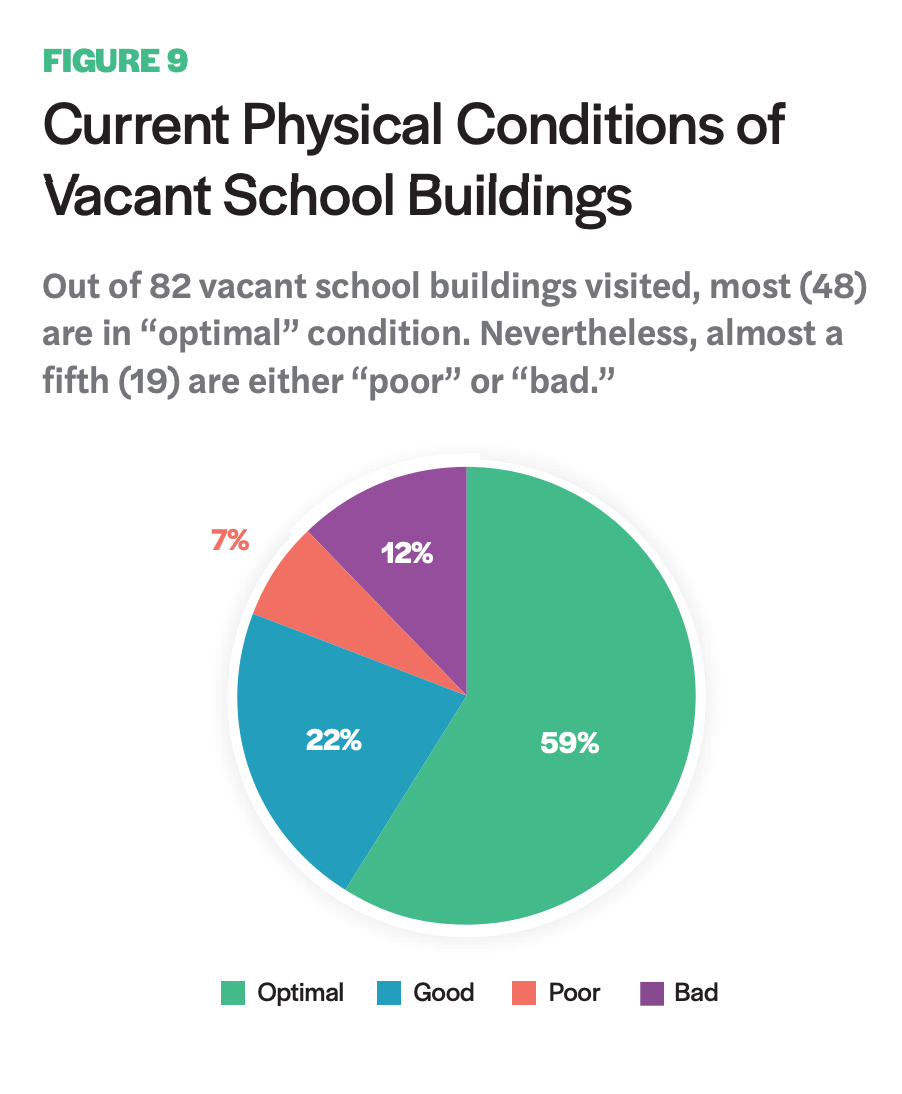

We identified a variety of cases of dilapidation, evaluating and categorizing the current physical state of vacant closed schools utilizing a scale of 1–4. On the scale, 1 was “optimal” (lack of cleanliness, paint, or upkeep of green areas), 2 was “good” (with vandalism and damaged or stolen air conditioner units, windows, doors, or railings), 3 was “poor” (with chipping walls, roof leakage, broken tubing, and rusted metal), and 4 was “bad” (with structural problems or broken walls). Of those vacant schools visited, 48 (59%) were classified as “optimal,” 18 (22%) as “good,” 6 (7%) as “poor,” and 10 (12%) as “bad” (figure 9). Of those listed as “bad,” 2 (or 20%) were recently closed in 2018 and 4 (40%) were closed in 2017, demonstrating the potential for rapid deterioration.

As for nonofficial uses, one prevalent and improvised use for 9 (11%) vacant schools included converting sites to clandestine horse stables for nearby residents, which has been reported throughout the archipelago, though these processes are haphazard and often do not involve full participation from the community. Finally, only one school (1%) was inhabited by persons and another 4 (5%) had evidence of casual human use, such as used mattresses or evidence of drug use.

In some areas, parents were working to reopen their closed school. “The community fought for four years to keep the school open. We were told that the closure was going to happen, that it was a done deal. They did close it, but we are still fighting to reopen it,” shared a parent in Aguas Buenas. Following a wave of earthquakes that devastated Puerto Rico’s southern municipalities in early 2020, and facing a growing inventory of still-open schools that have been deemed unsafe to occupy, Governor Wanda Vázquez is exploring the possibility of reopening previously closed schools to relocate affected classrooms at the time of writing.60 The destruction caused by the earthquakes to multiple open schools across Puerto Rico highlights the lack of criteria applied over the past decade to determine which schools close and why. Of the 82 vacant schools surveyed for this research, for example, 24 (29%) were single-level structures with 15 (18%) of these also in optimal or good condition.

Sales and Leasing of Closed Schools

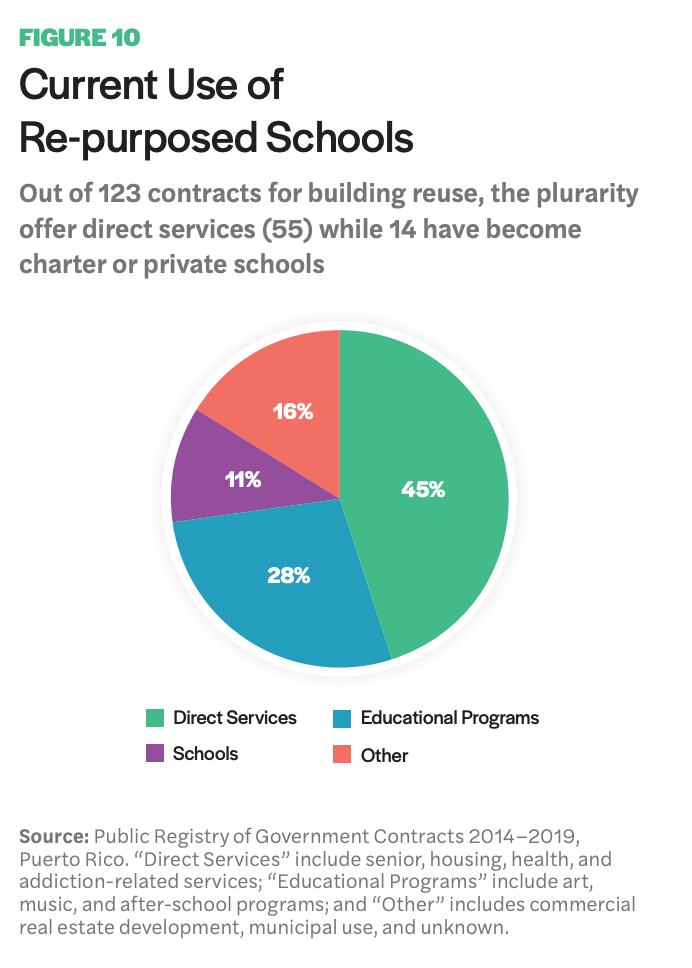

Following closure, public schools in Puerto Rico have been made available for lease or for sale, though the majority remain empty without contracts. Per available public records spanning from 2014 to 2019, Puerto Rico signed 123 contracts for sale, transfer, or leasing of school buildings for reuse. The number of contracted schools for reuse represents about a third of all schools closed since 2007, implying that up to four-fifths of closed schools remain without any usage plans. (These figures do not include schools that may have been leased or transferred prior to the contract registries available beginning in 2014, or via other seldomly used types of transfer.)58

Ten of the 123 contracted properties were sold (nine to corporations and one to an individual buyer). The average selling price was $411,300. The largest contract was in 2019 for a pair of schools on a single site for $780,000 to Mr. Bull, LLC, a company with ties to commercial office, retail, residential, and hospitality oriented real estate and development. This corporation is connected to two other entities that also bought school buildings in 2019: Mr. Blue Ocean and Shinrai Holdings, for $260,000 and $500,000 respectively. When the research team visited, none of these schools had been converted to shopping malls and were either still vacant or had undetermined current use. Of the ten purchased school buildings, one remains a school: Caguas Learning Academy, purchased by John F. Kennedy school for $470,000 in May 2019 and now runs a private for-profit school on the site. A total of 80% of all contracts are for leases with the symbolic amount of $1, demonstrating the limited revenue source reused schools offer.

The remaining 113 school buildings that were not purchased were leased to the following entities for various uses (figure 10):

- 14 for private and/or for-profit schools, and over one-third (5) of these new schools are Christian.

- 34 for educational nonprofits offering programs like after-school tutoring, arts and music classes, and daycares and Head Start programs.

The plurality of leased schools (55) are leased by direct service nonprofits, and some function as community or health centers, offering a range of programs including mental health and addiction psychological services, transitional housing, and services for seniors and people with disabilities. Out of all 123 contracts for school buildings from 2014 to 2019, 20 contracts (16%) composed of both sales (10) and leases (10) were expressly for private development in real estate, commercial development, or other purposes like “research.”

To measure the implementation rate of the above-mentioned contracts, an additional subsample of 50 of the 123 schools with sale, transfer, or lease contracts was selected for in-person site visits. Site visits revealed that less than half (22 or 44%) of sold, transferred, or leased schooled were actually in reuse, with 21 (42%) of the properties still vacant. For 7 (14%) of schools visited, researchers were unable to determine if the school was in use or not. Of vacant schools under contract, 10 (42%) suffered at least some degree of decay, such as vandalism (60%), illegal landfills (60%), and the accumulation of construction waste (40%) being among the most common characteristics.

Though nonprofit and community groups are technically allowed to compete side-by-side with for-profit and commercial entities for sale and lease contracts, the process to access a government contract can be bureaucratic and challenging for smaller community groups. One community leader who was able to facilitate a lease contract complained of the lengthy government processes, the lack of consistent regulations or guidelines, and increased pressure from the government to purchase at market rate instead of leasing.

- 54Emily Dowdall and Susan Warner, “Shuttered Public Schools: The Struggle to Bring Old Buildings New Life” (Philadelphia: Pew Charitable Trusts, 2013) 5.

- 55Lists available include official government-published lists from 2017 and 2018, as well as lists reported in the media from 2014 and 2016. A comprehensive list of 2015 closings was unavailable despite repeated requests and thus was excluded from the base population. The separate school lists were then compiled into a single database, from which 144 schools were selected via Microsoft Excel’s randomize list function.

- 56Upon visitation, 25 of the 144 schools (15%)—almost exclusively from the nonofficial 2014 and 2016 lists—were found to never have closed. Interviews with staff at these schools demonstrated that said schools at one time were earmarked for closure but, due to activism on behalf of affected families, mayors, and legislators, were saved from closing. Formal requests to the Commonwealth and its pertinent agencies for official lists prior to 2017 were never responded to, despite repeated written requests and freedom of information petitions.

- 59Jennifer Hinojosa et al., Population decline and school closure in Puerto Rico.

- 60Manuel Guillama Capella, “No Descartan Volver a Escuelas Que Se Cerraron,” Metro (January 16, 2020), https://www.metro.pr/pr/noticias/2020/01/16/no-descartan-volver-escuela….

- 58A number of schools were found to have been transferred from the government to a municipality or non-profit organizations through legislative action. In some cases, municipalities in turn transferred said school buildings to non-profit organizations.