We use the term “transformative research”9 to encompass a range of strategies for knowledge generation. Here are some common foundational principles across our experiences working in a variety of communities:

- Community self-determination: community members deciding who participates in what decisions that govern the research.

- Strategic action: oriented toward public action for equitable structural change.

- Power building: strengthens, deepens, and widens trusting relationships for shared commitment to transformation.

- Critical knowledge: commitment to reflection and learning for the sake of critical understanding and decolonization.

- Epistemic equity: honoring all forms of knowledge and centering lived experience.

Processes reflecting these principles can be transformative at multiple levels: the level of the individual, the group engaged in the work, organizations and institutions, and at a structural level.

Impact of Transformative Research at Multiple Levels

| Level of Transformation | Description of Possibilities |

|---|---|

| Individual Transformation | Experience can transform a sense of power or agency, an understanding of the interaction between the world and self, and knowledge for changing community conditions. |

| Interpersonal and Group Transformation | The process can transform relationships, shared purpose and commitments, and power in relation to institutions and networks. |

| Institutional Transformation | Transformative research can result in new organizations designed and led by people directly impacted by the work, and bring about new or reformed policies and public investments. |

| Structural Transformation | Transformative research can shift public narratives and norms, and change how entire sectors interact with the community. |

Here we have collected several trusted frameworks that we draw on in approaching a transformative research process. Some may fit better for you or your community.10 We encourage you to take what resonates but not try to use everything. If you have the energy and time, try something new, as these frameworks come from a variety of hard-earned experiences and they all work! Regardless of which framework best suits you, we encourage you to start with breathing as a metaphor to build a felt sense of what we mean by transformative research.

Breathing: A Metaphor and Grounding Activity

Just like we all breathe in and exhale, we all naturally and regularly take in information and use it to shape our actions. We observe, learn, and share our learnings from our experiences navigating our environment—this is a type of research, even if we may not intentionally be doing it. Breathing is innate, it is natural, and we do it without being conscious of it. In the same way, we learn and hold knowledge about how to survive and thrive, but it can be undervalued, and sometimes we don’t have time or space to notice and value it.

At its core, transformative research is a process of intentionally and consciously taking in something from the world around us, and putting out something from inside us, like the cycle of mindful breathing in and breathing out. When we mindfully breathe in, we take in what is around us with awareness and purpose. This means listening to our community and families, and observing our social and physical environment with intention, a process for reflecting on what we hear and observe, and mindfulness about how this changes our actions. When we breathe in, we are transformed by what we take in; it gives us life. When we inhale, we allow our diaphragm to be expanded by our external world. We integrate it into our own warmth and chemistry.

Then we breathe out with awareness and purpose. The exhale carries what is inside of us out into the world. Breathing out is like expressing what we know. It is the action we take that turns what is inside us into a force blowing out into the world. We can breathe out intentionally to transform a part of the world we most care about.

Breathing has transformative healing potential when we slow down and give our attention and intention to it. Similarly, knowledge about how to thrive is more powerful if we bring our attention to it and create space to notice, reflect on, and share it. In this way, transformative research can be part of healing justice, facilitating transformation within us to build power for transformative change around us. Remembering our head-to-heart connection and cultivating that open channel between our minds and hearts is a powerful form of healing. It is a way to catalyze liberated knowledge and action.

Popular Education

There is a deep historical relationship between PAR and popular education. As practiced by the Highlander Research and Education Center, “Popular education is the process of bringing people together to share their lived experiences and build collective knowledge.”12 This is a powerful way to build epistemic equity as people come to see that “between all of us, we know everything.”13 Brazilian founder of popular education, Paulo Freire, called participatory research “the educational component of the revolutionary process.”14

Self-determination in a research process means that community members with lived experience of the issue of concern are taking ownership of planning and carrying out research. This opens up the possibilities for transformative experiences as these community researchers “learn by doing,” cultivating critical knowledge within the research group. Those who have been part of a PAR process often say that the people who do the research are the ones who get the most out of it. Doing research transforms us. We gain new knowledge, new skills, and new relationships.

This builds power and collective commitment for transformative change by creating understanding of our conditions and what it takes to change them.

Cycles of Action and Reflection

PAR is not a methodology, rather it reflects an “orientation to inquiry” focused on collective knowledge generation for strategic action on a specific issue facing a community.15 As opposed to a conventional research process where a lead researcher would predetermine a set of questions and ignore what actions could be taken, PAR invites community members to embark on a journey by alternating back and forth between action and reflection.

A PAR cycle of action and reflection can last five minutes or five years, and anything in between and beyond. In five minutes, two people can interview each other and plan an action arising from their collective analysis. That is a cycle. In five years, a community research team can survey a representative sample of people across an entire city, create reports and charts about trends in their city, and take action for structural change. That is a PAR cycle. The five-year research cycle will also have many five-minute cycles that are part of it along the way.

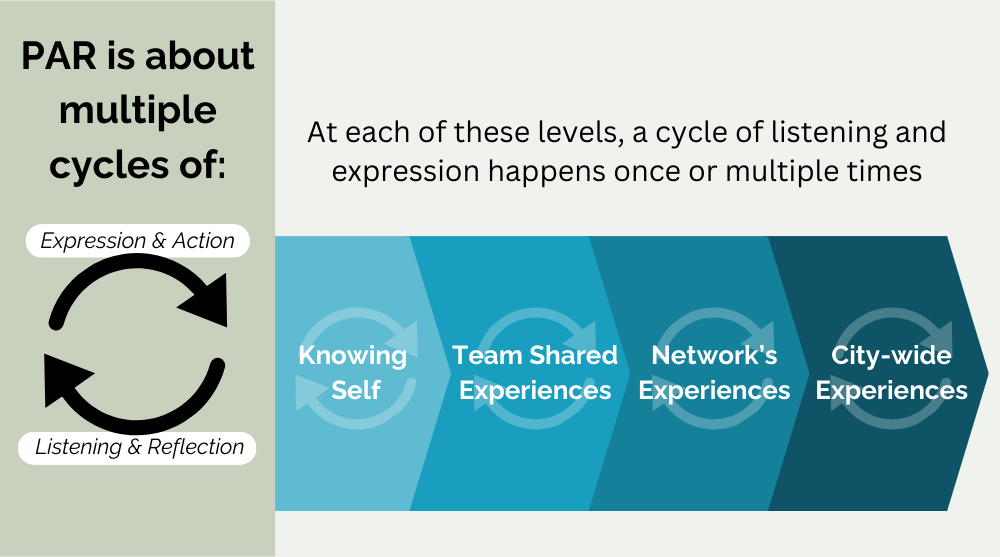

One way to think about a powerful research process is to picture a spiral that starts at the individual level, then goes to the level of the team, then the network of people who the team is connected to, and then to the whole city or the population that the team is focused on learning about. At each of these levels, a cycle of listening and expression happens once or multiple times. For instance, at the individual level, the cycle might be each of us “listening to ourselves” by doing a timeline of major events in our lives, then expressing ourselves by presenting this timeline to the rest of the team. At the team level, we might all interview each other and then compare our responses, then express them by writing a collective poem about who we are as a collective. At each stage, we are collecting new information and expanding the strength of our analysis for collective, beneficial action.

Research Justice: Dismantling the Pyramid of Whose Knowledge Counts

What counts as knowledge? Whose knowledge has been valued as most legitimate?

These are political questions, and when we honor the many forms of knowledge that our communities have, we expand the possibilities for a more just world. Research justice is a framework put out by the DataCenter based on its decades of experience collaborating with social movements on research. In their extremely useful Introduction to Research Justice toolkit, the group redefines “research” and “expertise” as follows:

An important part of the path to Research Justice is debunking the myth that expertise is limited to formal education, or that research is a skill reserved for the advantaged few. People use research methods in their daily lives to acquire knowledge to improve their lives. They have expertise in both the problems they face and the solutions they need. This toolkit helps readers engage communities to recognize their own expertise.17

Research justice illuminates how the hierarchy of what types of knowledge are valued and legitimate shapes power and policy because it marginalizes the voices of people holding the less valued forms of knowledge. The figure below provides a visual of the dominant hierarchy of types of knowledge, compared to a research justice vision that values experiential, cultural and spiritual, and mainstream knowledge.

Inequitable access to universities, data sources, and other research resources creates and perpetuates epistemic inequity. It means that communities left out of this infrastructure have less ability to mobilize their knowledge compared to the mainstream, or dominant forms of knowledge, like technical reports, professionally certified expertise, and statistical analysis. This is part of why reclaiming research is powerful—because it gives communities the means to produce critical knowledge like survey results or maps that are often treated as more valid by people with institutional power.

The Introduction to Research Justice toolkit provides workshop curricula, visuals, definitions, and other materials useful for facilitating a participatory process rooted in the research justice framework. The following bingo game is a fun tool that is part of a workshop on centering community knowledge as expertise.

Tending a Flower: Planning a Generative Process

The Flower of Praxis is a tool developed by Partners for Collaborative Change that uses the cycle of a flower growing from seed to full bloom and back to seed as an analogy for a generative PAR process.19 We like this metaphor because as much as you talk or think or study how to grow a flower, at some point you have to do the actual work of applying your thinking. This is why it is called the Flower of Praxis, with praxis meaning the iterative process of taking deliberate action through moving between theory, reflection, and action. The seed cannot grow and flourish on its own. Each part of the cycle requires mutuality and collective care from the soil, the sun, the bees, and other insects and from the seed and plant itself. Therefore, each of the steps below is cocreated and held by collective governance rather than by any one individual. The power is shared, and the benefits of the research and actions are shared. The cycle goes like this:

- Preparing the soil—cultivating a fertile foundation for the work ahead: This step is about building the readiness for a PAR process, including creating shared principles and values, identifying the focus of the work, outlining the where, who, when, and team and capacity building.

- Sprouting and growing strong roots—personal and collective reflection: This step is about learning from yourself and others about what issues and priorities you and your community have or want to address. This is also about internal and collaborative transformative growth. Uncover the nuances together to identify themes and goals for the work.

- From seedling to small plant—generate critical questions and research design: What big questions do you have that are important to find answers to in order to achieve your shared goal? These questions will guide the research. Who will you ask (sample)? How will you ask them (methods)? How will that translate into the tools you will use to collect your data?

- Plant maturation—implementing your research plan: This step involves applying your research tools to collect data, analyze your data for findings, and recommend action.

- Plant blooms—taking informed and strategic action: This step leads toward finding solutions in your community.

- The flower is pollinated: The fruits of your labor come to fruition, meaning real change has happened as a result of the research and action.

- The flower goes to seed: This is the phase where you turn inward to reflect on the lessons learned and reorient yourself, your team, and community to repeat the cycle. The seed is planted back into the soil, and the iterative process repeats.

More Transformative Research Frameworks and Resources

There are many more frameworks and ways to approach PAR and other versions of transformative research. Often, people define their approach through an epistemic or worldview frame that explicitly names their knowledge system and political lineage. Here are a few frameworks and resources that we have worked with:

| Framework | Description | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Feminist PAR (FPAR) |

“FPAR creates new forms of collaborative relationships essential to empower women and to amplify their voices and foster agency. FPAR is a political choice (as is all research) that starts with the belief that knowledge, data, and expertise is gendered, has been constructed to create privileged authorities, and that women have existing expertise that should frame policy decision-making.”20 | “Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR)” by Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development |

| Street PAR |

A methodological PAR framework that is led by folks that are “active in the streets or active in crime as a lifestyle, worldview, or cultural orientation…, and/or folk who are formerly incarcerated or returning [community members].”21 It centers street-identified people via their language; perspectives, lens, worldview, and assumptions; physical and social environment; and intersectional identities while recognizing their expert indigenous wisdom. Street PAR is also about reclaiming narratives about street-identified communities and building organizing power for structural change. Street PAR insists on practicing the most participatory form of PAR (i.e., not just having street-identified people collecting data), equitable compensation, and intentionally connecting street-identified BIPOC folks to community institutions to build power. |

“Street Participatory Action Research in Prison: A Methodology to Challenge Privilege and Power in Correctional Facilities” by Yasser Payne and Angela Bryant |

| Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR) | CPAR focuses intentionally on questions of power and injustice, intersectionality, and action. CPAR views critical research as one more resource in, by, and for movements for justice.22 |

Essentials of Critical Participatory Action Research, by Michelle Fine and María Elena Torre

|

| Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) | “YPAR is an innovative approach to positive youth and community development in which young people are trained to conduct systematic research to improve their lives, their communities, and the institutions intended to serve them.”23 | |

| Community-Engaged Scholarship | “Community engagement describes collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity. The purpose of community engagement is the partnership of college and university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching, and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good.” |

- 9We do not seek to replace or delegitimize other terms or frameworks for research, nor do we want to gain status by coining a new term. We felt that the frameworks we were familiar with were not inclusive of all the practices and strategies that we see as valuable for community-led transformation. So we see “transformative research” as an umbrella term, an entry point to various frameworks for research oriented toward social transformation.

- 10There are many frameworks for participatory action research (PAR) and justice-oriented research. We have narrowed it down to ones that complement each other and reinforce transformative principles in ways we felt support creative application for communities. Other wonderful frameworks and steps to PAR are listed at the end of this section.

- 12“Mission and Methodologies,” Highlander Research and Education Center, 2021, https://highlandercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/methodologies-EN-color-1.pdf.

- 13Ibid.

- 14Paulo Freire and Myra Bergman Ramos, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York, NY: Seabury Press, 1970).

- 15“Participatory Action Research and Evaluation,” Organizing Engagement, https://organizingengagement.org/models/participatory-action-research-and-evaluation/.

- 17Reem Assil, Miho Kim, and Saba Waheed, An Introduction to Research Justice (Oakland: DataCenter, 2015), 5, https://www.powershift.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/Intro_Research_Justice_Toolkit_FINAL1.pdf.

- 19See Partners for Collaborative Change, http://www.collabchange.org/.

- 20“Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR),” Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development, https://apwld.org/feminist-participatory-action-research-fpar/.

- 21Yasser Payne, interview with Ashley Bohrer and Justin de Leon, Pedagogies for Podcast, podcast audio, November 11, 2021, https://kroc.nd.edu/news-events/podcasts/topics/street-participatory-action-research-methodology/.

- 22Michelle FIne and Maria Elena Torre, “Essentials of Critical Participatory Action Research,” American Psychological Association (2021): 3 - 19, https://doi.org/10.1037/0000241-001.

- 23See “Why YPAR,” UC Berkeley YPAR Hub, https://yparhub.berkeley.edu/why-ypar.