Executive Summary: California is at a tipping point; both the government and private market are failing to meet the needs of a vast majority of the state’s 17.5 million renters. Skyrocketing rents, intensifying threats of eviction, and ongoing displacement are all part of a broader crisis of widening inequality and structural exclusion that is testing our values and identity as a state. The consequences are far-reaching: people are being pushed out of their communities, into homelessness, and away from jobs and opportunity. As a state, we face health, environmental, economic, and societal costs that can last generations. The extent of these long-term harms will be determined in large part by how we respond today. This moment requires that local governments have the ability to enact immediate solutions to protect tenants from unfair rent increases as well as wholesale evictions.

Download a PDF of this report here

Watch a recording of a presentation by the report's co-authors Nicole Montojo and Stephen Barton above, and visit this page for a transcript.

In this Brief

Part I: California’s Housing Crisis

In this section, we take a long-term view of the housing affordability and displacement crises, looking both decades into the past and out to the future, to understand the statewide impacts of rapidly rising rents. From this analysis, we draw five main conclusions:

-

California has reached a tipping point where policies and the private market are failing to meet the needs of the majority of renters. There are over 9.5 million Californians living in rent-burdened households and there has been a startling increase of approximately 3.7 million rent-burdened tenants since the year 2000.

-

The housing crisis also harms Californians’ physical and mental health. Exposure to hazardous conditions in the home, social isolation, severe stress, and other health problems are being exacerbated.

-

Rising rents have pushed many residents into homelessness. California now has the largest number of people experiencing homelessness among all 50 states, and research shows a clear link between rising rents and increased homelessness.

-

Stabilizing rents would have broader benefits to the state’s economy, environment, and public services—from improved traffic conditions and reduced traffic-related greenhouse gas emissions, to increased spending by tenants in their local economy.

-

Seniors, Latinos, African Americans, low-wage workers, and families with children face the most severe burdens from the housing crisis. Rapidly increasing rents are displacing residents to areas with fewer quality jobs, well-performing schools, and other resources—reproducing racial segregation, particularly in suburban areas far from urban jobs centers.

Part II: The Need for Rent Control in Achieving Housing for All

The numerous, far-reaching impacts of the housing affordability crisis, and the inability of the current market and government policies to resolve them, point to a pressing need for policy change. Part II of this research brief focuses on the rationale for rent control policy and the importance of allowing government to fulfill its responsibility to rebalance the broken housing market and advance public well-being. We discuss the specific function of rent control policies, situating them within a broader set of strategies to address the housing affordability crisis in both the near and long term.

This brief is not intended to provide a detailed policy agenda or propose specific policy designs, as we know that this must come from further conversations that involve a full range of stakeholders. Instead, we focus on where we believe the conversations must start—with opening the door for local governments and the state to design and enact rent control policies that can truly address the immediate needs of California’s renters.

While it will not solve the housing affordability crisis on its own, rent control is part of a needed adjustment to the rules of the market to ensure Californians’ access to housing.

-

Rent control has several unique, essential benefits related to current housing challenges facing California. The policy can stabilize rents for existing tenants, improve affordability for tenants in the future, and preserve the existing affordability of housing that may otherwise become unaffordable.

-

Rent control is a cost effective policy with immediate effects: Where most other programs require tremendous financial resources and take a great deal of time, renter protections can be established as a matter of law and the administration of rent control is typically paid for through modest per-unit fees.

-

The disadvantages of rent control policies do not outweigh its benefits. Claims that rent control has negative effects on development of new housing are generally not supported by research, but if there are some modest effects in that direction, they should be mitigated by other policy and investment mechanisms. The urgent need for stabilizing rents for tenants in the state makes this a policy priority.

-

Housing production is needed, but only rent control will provide a near-term solution for renters. The magnitude of California’s housing shortage indicates just how long-term any effort to resolve the crisis must be. The state currently has an affordable housing gap of 1.5 million homes for extremely low- and very low-income households, and overall, it needs to build 3.5 million new homes by 2025 to accommodate current demand, pent-up or latent demand, and projected population growth. Thus, rent control can provide a timely solution that the market will not.

While millions are struggling with housing instability and the threat of displacement due to extreme rent increases, our policy debates over solutions are too narrow when it comes to the needs of renters. Laws like Costa Hawkins have placed restrictions that limit communities’ ability to meet the needs of those who are hardest hit by the crisis—and furthermore, establish a path toward a better quality of life for all Californians.

These restrictions on rent control ought to be lifted in order to expand the conversation and create the possibility for a more equitable future in which all Californians can belong and thrive. The failures of past policy, along with our dysfunctional rental housing market, require us to reframe the policy objective at hand and focus on how we can create true belonging—structural inclusion where institutions and policies meet and are responsive to peoples' needs. If we start with this goal, we need a different policy question, one that prioritizes those among us who are disproportionately impacted by the housing affordability crisis:

How do we protect over-burdened renters from displacement and increase the supply of housing to meet the needs of people at all income levels?

We assert that California can and must do both—protect cost-burdened renters from exorbitant rent increases and forced moves while also producing new housing, provided that we take a comprehensive approach that includes rent control among multiple policy mechanisms and investments. This brief seeks to provide a framework to inform further statewide conversations on how government must answer the key policy question we put forward.

By responding to the urgent needs of residents facing displacement, rent control gives us a chance to continue working on a long-term strategy that integrates renter protections with housing production. The key concern is timing. While rent control alone will not solve the housing crisis, it is arguably the only viable policy that can act at the speed and scale needed. Tenants need immediate relief from extreme hardships they face, and we cannot afford to wait.

Moreover, rent control serves as a foundation for healthy communities, as well as an initial step toward repairing the harm caused by the broken rental market and past government actions that have segregated our cities and systematically disadvantaged low-income people and communities of color. By providing a baseline for housing stability, it creates an opportunity for us to ask a different question, to imagine the possibilities that come with a more equitable society:

What if all Californians had the stability and access to opportunity needed to fully participate in our democracy, contribute to their communities, and take part in the collective effort to advance the public well-being?

For California to even be able to consider this question, we must first and foremost protect and prioritize existing residents’ stability. Rent control can preserve people’s access to emerging opportunities in their current neighborhoods and help open up new housing choices that come with increased financial stability. It allows residents to remain a part of the communities that they have invested in and built, access well-paying jobs, and build savings that facilitate upward mobility. It provides families with the ability to have peace of mind, to plan for a future, and to belong to a community. We assert that these benefits, as well as the broader societal benefits that they contribute to, are invaluable. California must strive toward achieving them by upholding housing stability for renters as a key public policy goal. To do this, cities need to be able to have these conversations about policy design and consider all options that may be necessary to ensuring the broadest range of benefits to their citizens.

--------

Editor's note: This report was updated on Oct. 12, 2018 to correct comparability issues with US Census Bureau data from the 2000 Decennial Census and American Community Survey, as well as an error in the data on renter cost burden by race and ethnicity shown in Figure 5.

Introduction

California’s housing affordability crisis is harming communities across the state, stripping people of their incomes, disconnecting families from each other, restricting opportunities, forcing people into homelessness, and generating new patterns of segregation and stratification. Housing insecurity, unmanageable rent increases, and the threat of displacement carry deep consequences, since having a home is about more than just having shelter. Home is a locus of opportunity—it shapes the access people have to good schools and jobs, clean air, safe neighborhoods, and upward mobility. In other words, a stable, secure home is essential to human health and well-being.

The impacts of the housing crisis in California are intensifying racial and economic inequality. A decade after the Great Recession, many of those who lost their homes to foreclosures are still not able to again become homeowners. The high cost of rent forces Californians to pay for housing with income they could otherwise put toward education, retirement, investments, and other productive uses that increase economic opportunity. It compounds the difficulty in becoming a homeowner by making it more challenging to save resources for a down payment on a home. Bottom line: the crisis does not just harm the people overburdened by housing costs, it is harmful to the very fabric and well-being of the larger communities.

The housing crisis stands in stark contrast to Californians' widely-held inclusive values and broad support for equitable policy. In a recent survey of Californians’ views, two-thirds of residents agreed with the statement, “We are all in this together. If some people are in poverty or struggling, we need to work together to alleviate the problem and help each other.”1

Yet the housing affordability crisis is putting these values to the test. Housing costs are largely responsible for California having the highest poverty rate in the nation when factoring in the cost of living. One out of five Californians are in poverty.2 Many Californians faced with unaffordable rents have to move involuntarily, pushed to the fringes of our communities if they are even able to stay in California at all.

In a deeper sense, this crisis is about who belongs— who has the ability and right to stay in their community. It is also about the consequences of othering—what Californians as a whole stand to lose if we turn our backs, displace, and exclude certain members of our society—for how we live everyday. The crisis threatens our collective ability to thrive, our progress, and vision for a fair society—the very core of what makes California what it is. It raises the question of how we can create true belonging—structural inclusion where institutions and policies meet and are responsive to people's needs.

In a recent survey of Californians’ views, two-thirds of residents agreed with the statement, “We are all in this together. If some people are in poverty or struggling, we need to work together to alleviate the problem and help each other.”

When California residents were asked in the statewide survey, “How important is it that Californians work together across racial groups to create fair and equitable public policy for everyone?,” 66 percent responded “very important.”

This research brief seeks to describe the housing challenges California faces, the particular burden on renters, and the role of rent control policies in providing a necessary part of the solution. In Part I of the report, we analyze rental housing prices, populations affected, and the effects on homelessness, health, the environment, and the economy. Five findings stand out:

- California has reached a tipping point where policies and the private market are failing to meet the needs of the majority of renters. A majority of California renters (54 percent) are overburdened by housing costs, meaning that they spend 30 percent or more of their income on housing.3 This translates to over 9.5 million Californians living in cost-burdened renter households.4 Amid rising rents and stagnating wages, over 23 million jobs (73 percent of all jobs in California) do not provide enough compensation for workers to afford the current fair market rent (Figure 3).5 Low-income renters bear the greatest burdens. In order for a minimum wage worker in California to afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent, they would need to work 119 hours per week—the equivalent to three full-time jobs—putting affordable housing simply out of reach.6

- The housing crisis also harms Californians’ physical and mental health. Research shows that when families are faced with housing insecurity or displacement, they are often forced to make tradeoffs between meeting their basic needs, severely affecting physical and mental health.7 Their only option may be to accept poorly maintained housing that exposes them to a range of safety hazards, including pests and mold that can cause asthma, lead and other harmful toxins, as well as dangerous appliances and fixtures that can cause physical injury.8 Unhealthy conditions, combined with disconnection from one’s community, social networks, and sources of support, can result in stress and emotional trauma. Compared to those with stable housing, people experiencing housing insecurity are nearly three times more likely to be under frequent mental distress.9

- Rising rents have pushed many residents into homelessness. California now has the largest number of people experiencing homelessness among all 50 states. On a given night, over 134,000 people experience homelessness in California.10 This number increased by nearly 14 percent—over 16,000 more individuals—between 2016 and 2017 alone, and trends indicate a clear relationship between increases in rent and the growing number of people experiencing homelessness.11 A recent study estimates that in Los Angeles, a 5 percent increase in rent would lead to roughly 2,000 additional people experiencing homelessness.12

- Stabilizing rents would have broader benefits to the state’s economy, environment, and public services. Teachers, health service providers, service workers, and others are being priced out of the places where they provide services. This increases traffic, creating a ripple effect on other residents and exacerbating greenhouse gas emissions. Workers without stable housing and/or health conditions struggle to find and keep their jobs, and job losses can lead to a downward spiral into poverty.13 If all California renters paid only what they could afford on housing, they would have $24 billion more each year to spend in the economy.14

- Seniors, Latinos, African Americans, low-wage workers, and families with children face the most severe burdens from the housing crisis. Rapidly increasing rents are displacing residents to areas with fewer quality jobs, well-performing schools, and other resources—reproducing racial segregation, particularly in suburban areas far from urban job centers.15 According to a Federal Reserve study, “Low income renters with children pay a median of three-fifths of their monthly income on rent, leaving under $450 in residual income” to cover their remaining living expenses.16

Part II of this research brief focuses on the rationale for rent control policy and its role in a broader set of strategies to address the housing affordability crisis. We examine the need for policy specific to protecting existing renters in the state, the inability of the current market and government policies to resolve the crisis, and the function of rent control policies.

- Government actions improve neighborhoods, resulting in housing price increases, and the public has a responsibility to limit the passing on of these costs to tenants. When public schools,17 air quality,18 neighborhood safety,19 or public infrastructure like parks20 improve in a neighborhood, the prices of homes and rents in that neighborhood tend to rise. Yet these improvements are largely a result of public action, such as increased public funding, new regulations, and smart planning. In other words, government action is responsible for a portion of increased property values, no matter what property owners do. Limiting how these costs are passed on to tenants can reduce the burden on tenants.

- Government has a legitimate role in rebalancing broken housing markets to advance public wellbeing. The rental housing market in California is broken; windfall profits are being made in large part due to forces that have nothing to do with the investments or actions of property owners. When the housing market is as dysfunctional as it is in many parts of California, tenants are effectively subsidizing landlords with rent payments above what a fully competitive market would allow landlords to charge. In various other areas of life, the state has intervened to limit profits to what would be charged in a fully competitive market while still ensuring a fair return on investment. The US Supreme Court and California courts have consistently ruled that owners of rent-regulated properties have a constitutional right to a fair return on investment, so no rent control policy will eliminate the right of a landlord to turn a reasonable profit.21

- California can protect cost-burdened renters from exorbitant rent increases and displacement while also increasing the needed supply of housing, provided that we take a comprehensive approach that includes rent control among multiple policy mechanisms and investments.

- Rent control has several unique, essential benefits related to current housing challenges facing California. The policy can stabilize rents for existing tenants, improve affordability for tenants in the future, and preserve the existing affordability of housing that may otherwise become unaffordable.

- è Rent control is a cost effective policy with immediate effects: Where most other programs require tremendous financial resources and take a great deal of time, renter protections can be established as a matter of law and the administration of rent control is typically paid for through modest per-unit fees.

- The disadvantages of rent control policies do not outweigh its benefits. Claims that rent control has negative effects on development of new housing are generally not supported by research, but if there are some modest effects in that direction, they should be mitigated by other policy and investment mechanisms.22 The urgent need for stabilizing rents for tenants in the state makes this a policy priority.

- Housing production and tenant protections are needed, but only rent control will provide a near-term solution for renters. The magnitude of California’s housing shortage indicates just how long-term any effort to resolve the crisis must be. The state currently has an affordable housing gap of 1.5 million homes for extremely low- and very low-income households,23 and overall, it needs to build 3.5 million new homes by 2025 to accommodate current demand, pent-up or latent demand, and projected population growth.24 Thus, rent control can provide a timely solution that the market will not.

Amid California’s housing affordability crisis, our policy debates over solutions have become myopic when it comes to the needs of renters. Narrow debates have limited government’s ability to meet the needs of those who are hardest hit by the crisis. Too often, rent control policies are dismissed out of hand without considering the full range of their benefits. The key policy question is, can we protect overburdened renters from exorbitant rents and displacement while also increasing the needed supply of housing? We believe the answer is “yes.”

Government’s responsibility is to protect the public interest, and it has a rightful role in rebalancing the dysfunctional housing market to restore fairness between renters and property owners. We must let government fulfill its duty by removing state restrictions that hinder jurisdictions from designing and implementing rent control that works.

Part One: California’s Housing Crisis

Rising Rents & Stagnating Wages are Setting Renters Back

All Californians have experienced the impacts of today’s housing crisis in one way or another, but for decades the state’s low-income renters have carried the largest burden of housing costs. While rents have risen rapidly since 2011 in California and in the US as a whole, California rents have increased faster than the rate of inflation for most of the past forty years. The state’s largest metropolitan areas have faced the most severe crises, with rents increasing at far faster rates over a longer period of time (Figure 1). According to the US Census Bureau, the median contract rent in the Los Angeles area is 50 percent higher than the rest of the US, and the median contract rent in the San Francisco Bay Area is nearly double the national median.25

As rents have risen, renters' incomes have not kept pace (Figure 2).26 While it would take an hourly wage of $32.68 to afford the fair market rent (FMR) and utilities for a two-bedroom apartment, the mean wage among California renters is just $21.50 per hour.27

Too Many Californians Cannot Afford the Cost of Rent

- A majority of California renters (54 percent) are overburdened by housing costs, meaning that they spend 30 percent or more of their income on housing.28 This translates to over 9.5 million Californians living in cost-burdened renter households.29 Seven of California’s top ten sectors (by number of workers employed) do not pay enough on average for employees to afford the state’s fair market rent ($1,699 for a two-bedroom apartment, as estimated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development).30 31 In total, over 23 million jobs (73 percent of all jobs in California) do not provide enough compensation for workers to afford the current fair market rent (Figure 3).32 These include essential jobs in office and administrative support, retail and sales, food and restaurant service work, and transportation and material moving.33

- Extremely low- and very low-income households face the greatest hardship, with 77 percent and 48 percent spending more than half of their income towards rent, respectively.34 In order for a minimum wage worker in California to afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent, they would need to work 119 hours per week— the equivalent to three full-time jobs—putting affordable housing simply out of reach.35

- The impact of housing costs on California’s lowest-income households sets the state apart from the nation. California has the highest poverty rate (20.4 percent) among all 50 states according to the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which takes into account differences in housing costs across the US.36

Among those who earn less than what is needed to afford the fair market rent are the millions who comprise the backbone of the economy. They help California meet some of its most fundamental and important needs, and they perform some of the most strenuous and thankless tasks. These occupations include food service and restaurant workers like servers, cooks, and dishwashers; health service providers like medical assistants and home health aides; educational occupations including preschool teachers, child care providers, teacher assistants and school bus drivers; and domestic workers like housekeeping and janitorial staff.

The combination of stagnating wages and increasing rents has limited the ability of renters, including the many who lost their homes during the 2010 foreclosure crisis, to recover from the recession’s devastating impacts. Housing cost burdens for renters remained at nearly the same level five years after the crisis (55 percent in 2015 and 56 percent in 2010). By contrast, rates of housing cost burden among homeowners fell from 43 percent to 33 percent over the same period, demonstrating the increasingly disparate impact of the housing affordability crisis on renters (Figure 4).

Beyond Monetary: the Human Cost of Housing Instability and Displacement

Research shows that when families are faced with housing insecurity or displacement, they are often forced to make tradeoffs between which basic needs to meet, which can severely affect physical and mental health.37 38 Their only option may be to accept poorly maintained housing that exposes them to a range of safety hazards, including pests, mold, lead and other harmful toxins, as well as dangerous appliances and fixtures that can cause physical injury.39 Many in California are forced into overcrowded housing arrangements, which can affect mental health, stress levels, relationships, and sleep, and which may increase the risk of infectious disease.40 California now has the highest rate of overcrowding among renter households (13.6 percent) in the country.41 Unhealthy conditions, combined with disconnection from one’s community, social networks, and sources of support, can result in stress and emotional trauma. Compared to those with stable housing, people experiencing housing insecurity are nearly three times more likely to be under frequent mental distress.42

Children who experience forced moves are particularly vulnerable. The Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative finds that the health impacts of residential displacement are “intense for children, causing behavioral problems, educational delays, depression, low birth weights, and other health conditions.”43 These can translate into poor academic performance, marked by lower test scores, frequent absences in schools, and a lower likelihood of finishing school.44 This can have a cascade of lasting consequences for many other aspects of life, which, when layered upon one another, further reinforce structural inequalities.

California now has the largest number of people experiencing homelessness among all 50 states. On a given night, over 134,000 people experience homelessness in California, 68 percent of whom go without shelter.45 This number increased by nearly 14 percent (over 16,000 more individuals) between 2016 and 2017 alone, and trends indicate a clear relationship between increases in rent and the growing number of people experiencing homelessness.46 A recent study estimated that in Los Angeles, a 5 percent increase in rent would lead to roughly 2,000 additional people experiencing homelessness.47 With a 4.2 percent increase in Los Angeles rents over just the past year, many more individuals are at risk of losing their homes entirely.48

This growing body of research shows that the lack of affordable, safe, and stable housing is associated with a range of negative impacts on individuals and families. Sociologist Matthew Desmond describes this relationship:

In the absence of residential stability, it is increasingly difficult for low-income families to enjoy a kind of psychological stability, which allows people to place an emotional investment in their home, social relationships, and community; school stability, which increases the chances that children will excel in their studies and graduate; or community stability, which increases the chances for neighbors to form strong bonds and to invest in their neighborhoods.49

On the other hand, protecting low-income residents’ ability to stay in their homes and neighborhoods supports greater access to those opportunities that make a healthier, safer society. Housing stability has positive effects on physical, social, and psychological wellness, as well as educational attainment.49

Broader Benefits of Housing Affordability: Fiscal, Economic, and Environmental Benefits to California

Housing for all is about more than stabilizing costs for individual families; it is also about advancing our collective well-being as a society. What if California renters paid affordable rent and thereby had $24 billion51 more available to cover basic needs and infuse into our economy? What if the nearly $5 billion that the state government spends on homelessness each year52 went towards an array of other public resources and programs? What if California could substantially reduce its poverty rate—the highest in the nation—by lowering its high cost of living?53

California is increasingly a renter state, with over 17.5 million Californians living in renter households, equivalent to an increase of approximately 27 percent in the renter population since 2000.54 Yet when we consider the impacts of California’s policy choices, we typically fail to account for the fiscal and societal costs of their exclusion. If we choose not to address the needs of such a large and growing share of our population, we choose to limit ourselves. Perhaps more critically, we fail to imagine the great economic, fiscal, and environmental benefits of their stabilization that can improve our health and prosperity as a society.

With the crisis so widespread, negative impacts at the individual level add up, reinforcing existing inequities and affecting the strength of our society overall—from our economy and public institutions, to our social fabric and democracy.55 By confronting this reality, we lay the foundation for a more prosperous, resourced, and healthy future.

The mental and physical health impacts of housing unaffordability and displacement require vast public resources, including $5 billion of state funding annually on services for homeless individuals,56 with county governments shouldering a large share of the cost and responsibility of delivering services. For example, in Santa Clara County where 6 percent of the state’s homeless population lives, more than $3 billion worth of services went to homeless residents between 2007 and 2012, costing the community $520 million per year.57 A study commissioned by the County of Santa Clara and Destination: Home shows that these costs included “$1.9 billion over six years for medical diagnoses and the associated health care services—the largest component of homeless residents’ overall public costs, as well as $786 million over six years associated with justice system involvement—the second largest component of the overall cost of homelessness.”58

This strain on our healthcare systems and public budgets—in addition to the exponential expansion of jails and prisons through an unjust system that criminalizes homelessness—undermine California’s ability to advance and provide for the many other underfunded public needs, including education and student financial aid, workforce development, and safety net programs. Our failure to respond to immediate crises of displacement and homelessness also limits us from investing in essential programs, such as “Housing First” initiatives to create permanent supportive housing, which can more effectively, efficiently, and holistically serve the needs of lowincome Californians, instead of constantly responding to emergency situations.59

Housing instability and resulting negative health outcomes also impact the state’s workforce, economy, and environment. Workers without stable housing and/ or health conditions struggle to find and keep their jobs, and job losses can cause a downward spiral into deep poverty.60 Additionally, both the public and private sectors face challenges in hiring and retaining workers for roles that keep our economy running. As displaced residents are pushed out to the periphery where fewer employment opportunities exist, many are forced to commute long distances to urban centers for work, and with less access to public transit in suburban areas, this requires greater use of private vehicles.61 The housing crisis is thus contributing to congestion on our freeways and more time spent in cars for all drivers, which are associated with lower rates of physical activity and higher rates of stress.62 Longer commute times result in clear environmental and public health impacts, including decreased air quality and increased greenhouse gas emissions. For displaced residents, this tradeoff carries both health and financial costs; for every dollar increase in housing costs, a household’s transportation costs increase by 77 cents.63

Inequitable Impact: The Housing Affordability Crisis Disproportionately Affects Seniors, Low-Income Families, People with Disabilities, and Communities of Color

In addition to the broad fiscal, economic, and environmental benefits, if all California renters paid only what they could afford for housing, California would move toward greater social equity, which is essential to an inclusive, stable, and sustainable economy.67 As it stands, the housing affordability crisis is exacerbating inequality, with seniors, Latinos, African Americans, low-wage workers, families with children, and people with disabilities facing the most severe burdens from the housing crisis. Rapidly increasing rents are displacing members of marginalized populations to areas with fewer resources, quality jobs, wellperforming schools, and other opportunities for upward mobility—essentially reproducing racial and socio-spatial segregation, particularly in suburban areas far from urban job centers.68

- California’s senior tenants face higher rates of rent burden compared to the rest of the population (61 percent compared to 51 percent of non-senior households).69 California Department of Finance projections show that by 2035, the majority of seniors (54 percent) will be people of color.70 As the senior population becomes more diverse, housing security for seniors also becomes a matter of racial equity.

- People with disabilities also face unique challenges in accessing affordable housing, contributing to increased vulnerability to homelessness. The California Department of Housing and Community Development reports that adults with disabilities are three times more likely to be homeless than adults without disabilities.72 Additionally, people with disabilities are more likely to face discrimination when seeking housing; the Department points out that 41 percent of discrimination complaints received by the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development were due to a person’s disability.73

- When disaggregated by race, data on rent burden and affordability show significant disparities: 64.1 percent of Black tenant households and 57.6 percent of Latino tenant households are burdened by housing costs (Figure 5). Furthermore, a recent study by Zillow found that less than one percent (0.6 percent) of rental listings in the entire San Francisco metropolitan area are within the typical Black household’s budget, compared to the nearly half (49.8 percent) of listings affordable to the typical white household.74

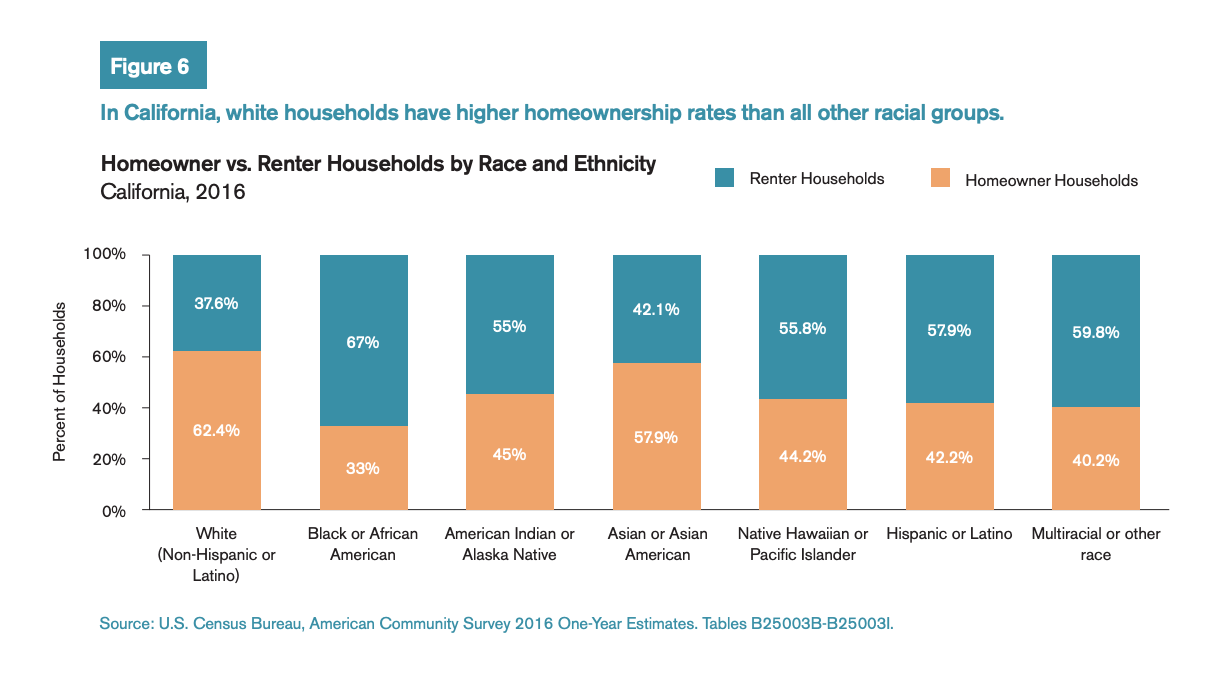

- Disparate rates of rent burden also contribute to disparate access to homeownership, as high rents keep families from being able to save for a down payment and other costs associated with homeownership. In 2016, only 33 percent of Black households and 42 percent of Latino households in California were homeowners, compared to 62 percent of white households (Figure 6).75 Moreover, while white homeownership rates in 2016 were only 2.5 percent lower than 2000 levels, homeownership among Black households has fallen by 6 percent since 2000.76

- Racial disparities are also reflected in the experience of homelessness; African Americans make up only 6.5 percent of the state’s population, but comprise 27 percent of persons experiencing homelessness.77

When housing costs increase beyond what is affordable, residents often have to relocate to an area with less expensive housing. This pattern of displacement is most glaring in historically low-income neighborhoods that are predominantly comprised of people of color. For instance, a significant share of neighborhoods at risk for displacement are also home to a majority people of color, including 83 percent of the at-risk neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area.78 This raises particular concern as data shows that in regions across the US, more rental units are out of reach for Black and Latino families compared to other households.

These statistics plainly show how exclusion and displacement occur; not only are lower-income families of color excluded from moving in, but if they were to lose their current home in a high-cost region like the San Francisco Bay Area, they would more likely be forced to move out of the region or out of California entirely to an area of lower opportunity. The failure to address this immediate crisis has dramatic long-term consequences, as the long-term residents of California’s urban core are pushed out and supplanted by a new, wealthier, and whiter population. This reinforces patterns of segregation that limit access to quality jobs, schools, and resources that promote upward mobility. This also contributes to a widening racial wealth gap, as evidenced by the disparities in homeownership by race.79 80

The racial and social inequities perpetuated by egregious rent increases and the housing crisis raise the stakes for the state as a whole, and communities of color, low-income individuals and families, people with disabilities and seniors, in particular. Increasing inequity between tenants and homeowners is a thread that runs through other dimensions of inequity that these historically marginalized groups face, and addressing this overarching divide allows us to move toward greater social equity overall. In other words, stabilizing rent for all tenants in California also means broadly addressing the critical needs of the most vulnerable among us, which is essential to achieving shared prosperity for Californians as a whole.

Part Two: The Need for Rent Control in Achieving Housing for All

The Public Response: Government’s Role and Responsibility

The numerous, far-reaching impacts of the housing affordability crisis, and the inability of the current market and government policies to resolve them, signify the need for policy change. The essential role of government is to protect the public interest, and to ensure that all members of the community are treated fairly and with equal dignity.81 To fulfill that role, government must periodically adjust the rules governing markets so they meet people’s needs as opposed to causing them harm. The rental housing market in California is currently in a moment that requires policy intervention. Rent controls are part of a needed adjustment to the rules of the market to ensure Californians’ access to housing. The current structure has resulted in a broken market and housing price increases. Its actions to improve neighborhoods also result in housing price increases, and it has a responsibility to limit the passing on of these costs to tenants. It also has a responsibility to fix broken housing markets to advance public well-being.

The Public’s Role in Creating Land Value

As anyone who has looked for housing knows, neighborhood conditions around a home are often as much a factor as the building itself.82 When the public schools,83 air quality,84 neighborhood safety,85 or public infrastructure like parks86 and public transit improve in a neighborhood, the prices of homes in that neighborhood tend to rise. Yet these improvements are largely a result of public action, such as increased public funding, new regulations, smart planning. Furthermore, public improvements as well as maintenance of public goods and services are made possible through the taxes paid by the general public, homeowners and tenants alike.87 Because land value tends to increase when public investments are made,88 regulation of land value simply recaptures value created by the public. As economic development expert Richard Rybeck writes, "Most members of the public end up paying twice for infrastructure. First, they pay taxes to create or improve infrastructure. Second, if they want to locate their home or business nearby, they must pay a landowner a premium rent or price to get access to the infrastructure that their taxes created."89

In sum, government action, which is supported by the collective contributions of all citizens, is responsible for a portion of increased property values, no matter what property owners do.90 In addition to government action, the public also creates tremendous value through myriad private interactions. California’s diverse peoples generate a creative culture that leads to technical and artistic innovation and a thriving economy, which in turn generates increased demand for access to the new jobs and the cities in which they are located.

Economists often mistakenly treat rental housing as a simple consumer good. In fact, rental housing involves two separable aspects: the building, and the land or location, as Adam Smith pointed out in The Wealth of Nations more than two centuries ago. The “building rent” is the amount actually necessary to pay for the operation and maintenance of a home and to provide a normal profit to the landlord on their invested capital. The “land rent” is an extra payment for access to a desirable location. For tenants in coastal California a substantial part of the rent is really just an admission charge for the privilege of living here.91 As Smith wrote in his seminal book on market economics, the land rent is “a species of revenue which the owner, in many cases, enjoys without any care or attention of his own.”92 Professor Lee Friedman points out that since the actions of the landlord determine the building rent but not the land rent, reductions in unearned land rent have no effects on the production and maintenance of housing.93 94

Requirements established in the California constitution ensure that rent controls will only limit increases in land or locational rent and will not limit necessary increases in building rent. That is because landlords are entitled to rent increases necessary to provide them with a “fair return” on their investment. These rent increases must be sufficient to compensate for any increases in the cost of operation and maintenance of the buildings they own, and ensure that their cash flow increases keep up with inflation. But rent control will limit the increases landlords can impose that go beyond what is needed for a fair return, increases that are an admission charge for access to locations in California.

We all, homeowners and tenants alike, contribute to making California a desirable place to live in. Our rental housing market is structured so that private landlords take this publicly-created value for private profit, charging tenants higher rent for their contribution. This allows real estate investors to exact an enormous transfer of wealth from people who do not own real estate to people who do. It disrupts the lives of individuals, families, and communities. Rent control policies can correct this by rebalancing fairness between tenants and landlords.

The Public’s Responsibility to Fix Broken Markets

Housing markets always depend on the rules that government enforces. It is not a question of whether there are rules, but what rules there will be, and what values and priorities those rules reflect. The debate over rent control is too often dominated by a false dichotomy in which government and the market are opposed to each other. In fact, government makes markets possible. Government establishes the detailed structure of law and regulation that defines the rights and obligations of the parties involved, and government provides essential public investments and services such as transportation, public safety, and education. Without these no market can function effectively in a modern society. Markets require appropriate public investments and regulatory oversight in order to deliver goods and services that are safe, fairly priced, produced by methods that do not damage the environment, and pay workers a living wage. Determining how government can best shape a particular market requires careful analysis, rather than an assumption that markets are inherently self-regulating.

When markets and the rules governing them work poorly, the owners who control production and allocation of necessary goods and services have disproportionate power and the market norm of maximizing profit leads to consequences such as extracting unnecessarily high prices from consumers, depressing wages, and damaging the environment. The rental housing market in California is an example of a market that is not working well. Windfall profits are being made in large part due to forces that have nothing to do with the investments or actions of property owners. When the housing market is as dysfunctional as it is in many parts of California, tenants are effectively subsidizing landlords with rent payments above what a fully competitive market would allow landlords to charge.

As previously noted, the US Supreme Court and California courts have consistently ruled that owners of rent-regulated properties have a constitutional right to a fair return on investment, so no rent control policy will eliminate the right of a landlord to turn a reasonable profit.95 But at various moments in history and in various areas of life, the state has intervened to limit profits to something closer to what would be charged in a fully competitive market while still ensuring a fair return on investment. For instance, public utility regulation allows the investor-owned companies that provide public necessities such as gas, electricity, and water to charge prices that provide a fair return on their investment. It does not allow companies to take advantage of the lack of sufficient competition in their market to charge consumers more than the price they would charge in a fully competitive market.

The public has both a legal and a moral right to make changes in law and regulation to ensure that investors cannot take advantage of markets that fail to protect the public interest. Housing is a basic human need, and in other markets when this happens, the state intervenes and protects the public from harm while still allowing for a fair return on investment.

Rent Control Policy Benefits and Limits

As described in Part I, data on rent burden clearly shows a crisis in housing affordability that is especially harmful for renters in California. While California is faced with a range of housing issues that require us to pursue various policy goals, the goal of addressing the housing affordability and displacement crises facing overburdened renters must be prioritized. Rent control is a key policy for meeting this goal, but restrictive state legislation and narrow policy debates have severely limited the ability of local governments to consider rent control policies and decide for themselves how to respond to their citizens’ housing needs.

Frequently the debate around rent control engages a divisive framework: we can stabilize rent for existing tenants, as studies have found the policy does,96 97 but some researchers and advocates contend that by doing so, we may slow the production of new housing supply. This flawed dichotomy undermines the overall goal of providing affordable housing for all, both now and in the future. In this framework, stabilizing rent for existing tenants is often considered just one of several policy goals. Instead, we argue for making an intentional choice to center the needs of existing renters in defining the policy objective at hand. Focusing entirely on other housing policy goals means ignoring the urgent and immediate needs of millions of overburdened renters across the state.

We argue for making an intentional choice to center the needs of existing renters in defining the policy objective at hand. Focusing entirely on other housing policy goals means ignoring the urgent and immediate needs of millions of overburdened renters across the state.

The Unique Benefits and Possibilities of Rent Control

- A cost-effective and responsive policy approach: Where most other programs require tremendous financial resources and take a great deal of time, renter protections can be established as a matter of law and the administration of rent control is typically paid for through modest per-unit fees. For example, rent board programs in Santa Monica and Berkeley are cost-neutral, with fees collected sufficiently covering all operating costs.98 Renter protections immediately advance the goal of stabilizing rents for historically marginalized residents who have built their communities and contributed to the value of their neighborhoods long before the present wave of economic development.99 As these places experience increased public investments in infrastructure and services, as well as new economic development and job growth, rent control helps to ensure that existing residents can benefit from the improvements that they helped create.

- Housing stability for existing tenants: Rent control is, first and foremost, an antidisplacement tool. The vast majority of academic studies on rent stabilization find that it increases renters’ ability to choose to remain in their homes.100 A recent study of the effects of rent control in San Francisco found that it increased tenants’ probability of staying in their homes by nearly 20 percent, and that without the financial savings that rent control provided, they would otherwise have left the city.101 The literature also shows that these effects of stability are greatest for older tenants and long-term tenants,102 thereby supporting aging in place and the preservation of community connections.

- Improved affordability: Several studies have shown that rent control provides financial benefits to current tenants. Research by UCLA professors William Clark and Allan Heskin on the early impacts of rent regulations in Los Angeles (prior to the enactment of Costa-Hawkins in 1995) determined that after living in rent-stabilized homes for three to five years, tenants’ rents were between 26.5 to 30.9 percent lower than market rent, and for those with tenure between five and ten years, this discount was as high as 36.8 percent.103 Although the evidence is mixed, some studies have found that in cities with rent regulations, even non-controlled units actually had slightly more affordable rents compared with units in cities without rent control.104 105 A recent study of the effects of rent control in San Francisco found that benefits to tenants averaged “between $2300 and $6600 per person each year, with aggregate benefits totaling over $214 million annually.”106 The financial benefits of rent control can help renters to not only meet their basic needs, but open up opportunities for individual advancement and well-being.

- Preservation of economic diversity: Egregious rent increases continue to place more of the existing housing stock out of reach for lower-income tenants, thus increasing California’s already overwhelming affordability gap. Rent control, particularly when combined with regulations related to condominium conversions and other renter protections such as “just cause for eviction” ordinances, can help prevent the expansion of California’s existing shortfall of housing for lower-income renters.107 In doing so, it can help to maintain economic diversity and integration. A study of the effects of lifting rent control in Cambridge, Massachusetts found that after the policy’s repeal, not only did the value of formerly stabilized properties increase by 18 to 25 percent in ten years, but the value of non-controlled units increased by 12 percent. The researchers suggested that wealthier households moved into the city after lower-income tenants had been displaced by unregulated rent increases, while they may not have been willing to move in prior to decontrol.108 This suggests that rent control can contribute to preventing displacement that would ultimately lead to more exclusionary, economically-segregated cities. As we note in the following pages, however, rent control is only a step in this direction and must be supplemented by additional government initiatives to raise incomes and reduce poverty.

Limitations of Rent Control

We acknowledge that in addition to rent control being just one part of the solution, it also has limitations and requires thoughtful policy design to mitigate any downsides. We believe that none of these limitations should preclude the use of rent control to prevent residential displacement, but it is important to consider and respond to these limitations when designing local programs.

- Means testing: A common critique of rent control is that it is not means-tested, and thus does not specifically target the renters that need it most. Proponents of rent control point out an important reality: that any means-testing would very likely lead to discrimination against low-income renters because landlords would be incentivized to evict eligible tenants or solely rent to non-qualifying tenants who could pay higher rents. Additionally, as detailed in Part I, data on rent burden rates indicate that a majority of renters do stand to benefit from greater housing affordability, and they rightfully should, as California's high rents reflect unearned increases in rent based on public investment and services, and scarcity conditions in which tenants are subsidizing landlords. There is no more reason to limit the benefits of rent control to the lowest-income tenants than there is to limit the benefits of public utility regulation to only the lowest-income users of electricity and water. We thus recognize that meanstested approaches are important and appropriate for other policies, but in the case of rent control, the lack of means-testing provides critical benefits that overcome this aspect of the policy.

- Potential effects on supply and tax revenues: Others raise concern that rent control may decrease housing supply109 and property values, and subsequently impact tax revenues.110 Yet, numerous empirical studies, as well as housing production trends in cities with rent control, show no negative effect on housing production, often finding that other local conditions and market cycles have a greater influence on supply.111 112 The three largest Bay Area cities with rent control (San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland) have only 27 percent of the region’s housing but according to the U.S. Census Bureau those cities have built 43 percent of the Bay Area’s new multifamily rental units in buildings with five or more units since 2000. Similarly, the City of Los Angeles, with 42 percent of the housing in Los Angeles County, has built 62 percent of new multifamily rentals since 2000.113 Other concerns, such as the potential loss of rental units due to condominium conversions, can be addressed through ordinances regulating condominium conversions, which nearly all California cities with rent control employ. Nonetheless, landlords may be able to take advantage of other loopholes, which should be addressed through additional changes in state law. On the other hand, rent control may involve tradeoffs, which require California to make an intentional choice about its priorities. While data suggests that it is not associated with a decline in property values,114 the Legislative Analyst’s Office notes that under strong rent control systems, tax revenue from residential rental property will rise more slowly.115 But inflicting enormous hardship on tenants, driving millions into poverty, and tens of thousands into homelessness, is too high a price to pay for generating more tax revenue. California has better options for raising the revenue we need for state and local government. Rent control’s benefits, both to renters and to the state as a whole, far outweigh the costs.

- Need for additional government action to create choice and opportunity: It is also critical to recognize that the need for reforms extends beyond rent control and housing policy more broadly. Although rent control can prevent forced displacement, for residents of neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, rent control alone may not be enough. Some extremely low-income families may be unable to pay even the lowest market-rate rent, or they may be prone to missing a rent payment and thus subject to eviction for just cause. The state must therefore ensure access to stable, living-wage jobs that allow families to weather any financial emergencies, comfortably afford rent month-tomonth, and build savings and assets over time. This is one part of ensuring not just stability, but full access to opportunity and choice—both the choice to stay in their current homes and neighborhoods, as well as the choice to move to areas where they may have greater access to opportunities for selfadvancement. Part of this must involve additional public investment in resources to improve school quality and employment opportunities, as well as other pathways to opportunity, mobility, and equity. Another factor is vigilant enforcement of laws already on the books, such as fair housing laws that protect renters from discrimination. Rent control provides a baseline for housing stability, but Californians must also work toward establishing stronger employment policies, more equitable tax structures, greater investment in the socially-owned housing sector, and other reforms that support the goals of social equity.

Putting Tenant Protection and Housing Production Together: Near and Long-Term Strategies

Rent control alone does not solve for the full range of Californians’ housing needs, but it addresses one key need held by a large segment of California’s population: the growing housing costs that burden over 9.5 million renters, while also advancing our state’s broader goals of social equity and progress. Rent control is first and foremost about protecting and prioritizing existing residents’ stability, which preserves access to emerging opportunities in their current neighborhoods and helps open up new housing choices that come with increased financial stability. It allows residents to remain a part of the communities that they have invested in and built, access wellpaying jobs, and build wealth that facilitates upward mobility. It provides families with the ability to have peace of mind, to plan for a future, and to belong to a community. We assert that these benefits, as well as the broader societal benefits that they contribute to, are invaluable. California must strive toward achieving them by upholding housing stability for renters as a key public policy goal. To do this, cities need to be able to have conversations about effective rent control policy designs and consider all options that may be necessary to ensuring the broadest range of benefits to their citizens.

Renter protection and housing production are not an either/or decision. California needs both in order to make room for both new and longtime residents, but without rent control to anchor our policy approach, the individual and societal consequences of the crisis will continue to intensify and harm California as a whole, while the benefits of all other policy efforts will manifest too late.

With California’s growing population and economy, it is clear that producing new housing is essential to meeting the state’s housing needs. We must continue to pursue changes that reduce barriers to housing production, especially of subsidized housing as well as multifamily housing that can be affordable by design. This includes developing new funding sources for affordable housing development and addressing exclusionary zoning policies at the root of the displacement crisis. But producing enough housing to fill the 3.5 million-unit gap is a long-term strategy, rather than a short-term part of the solution to displacement and housing poverty.

As discussed previously, the housing crisis is not a simple matter of supply and demand. The key concern is timing. Tenants need immediate relief from extreme hardships they face, and we cannot afford to stand back and hope that new housing “catches up” to demand and “trickles down” to create enough affordable housing. If our goal is to stop further displacement and expand access to places of opportunity in California, relying solely on the market simply will not work. In fact, any production strategy that does not include rent control and other protections will be insufficient.

The Role of Rent Control and Tenant Protections: Providing a Timely Solution that the Current Market Will Not

A Comprehensive Approach for California’s Diverse Housing Needs: Protection, Production, Preservation, Power, and Place

There is an emerging framework among researchers, community advocates, and policymakers of a comprehensive policy approach that includes five strategies (the “five Ps”): three which have been more traditionally referenced116 117 —protection, production, and preservation—as well as two important additions— power and placement.118 119 120 Rent control and other renter protections provide a necessary foundation for the remaining four Ps.

- Protection: protecting tenants and socioeconomically disadvantaged residents from displacement (e.g. just cause for eviction and rent control policies)

- Production: increasing the production of new housing by generating funding, removing exclusionary land use policy barriers, and other strategies (e.g. affordable housing linkage fees, public land policies, elimination of exclusionary zoning)

- Preservation: preserving existing affordable housing, including income-restricted units and units on the market that are rented at relatively lower rates (e.g. funding programs that support the acquisition and rehabilitation of older affordable rental units)

- Power: ensuring equitable community participation that leads to responsive and inclusive housing decisions (e.g. an expanded role for limited-equity cooperatives and community land trusts)

- Placement: creating access to housing for socioeconomically disadvantaged people in places that connect residents to opportunities and break patterns of segregation (e.g. fair housing laws and source of income discrimination laws)

The Magnitude of the Challenge

The magnitude of California’s housing shortage indicates just how long-term any effort to resolve the crisis must be. The state currently has an affordable housing gap of 1.5 million homes for extremely lowand very low-income households,121 and overall, it needs to build 3.5 million new homes by 2025 in order to satisfy current demand, address pent-up or latent demand, and accommodate projected population growth.122 Recent statewide measures such as SB 2 (Atkins, Building Jobs and Homes Act) and AB 1397 (Low, Adequate Housing Element Sites), both passed as part of the 2017 Legislative Housing Package, have begun to address barriers to market-rate and affordable housing production.123 However, analyses by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office and the UCLA Anderson Report indicate that it will take many years for additional production to slow the rate of increasing rents, let alone bring them back down to affordable rates.124

- If construction continues at the same pace since 2000 (an average of 1 percent each year), California will only build approximately 1.2 million homes by 2025125 —less than 35 percent of the total estimated need.126

- To merely keep California’s housing costs from escalating faster than the rest of the United States, the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) estimates in addition to the 100,000 - 140,000 units that are expected to be built annually, yearly production would need to increase by as much as 100,000 units, with most growth occurring in the state’s high-demand coastal communities.127

- However, actually reversing the trend and achieving even slightly more affordable levels would require far more. Using the LAO’s estimates, the UCLA Anderson Forecast finds that to achieve a modest 10 percent reduction in price, California would need to increase its housing stock by 20 percent, about 2.8 million additional units of housing.128

The Limits of Market-Rate Housing Production

California’s rental housing market is broken. It is not, and will not be, for the foreseeable future, capable of providing the amount of housing that low-income residents need. The current housing market requires tenants to compete for places to live and allows landlords to charge whatever the market will bear, leaving the lowest-income renters with the only option of paying to live in units that cost more than what they can afford.

The state does need to build new housing units to address the shortage, but it is critical to recognize that while more housing is needed at all income levels, the market is responding primarily to the demand for housing from middle- and upper- income people.129 130 As they come online, new market-rate rental housing units play an important role of addressing demand at the high end of the market. While primarily accessible to above moderate-income households, these new homes can contribute to preserving the relative affordability of older homes by relieving some of the pressure at the lower end of the market (where the need is greatest).

This new market-rate housing may eventually “filter down” to prices affordable to moderate and low-income tenants but this process can take generations.131 This will not solve the current shortfall of 1.5 million rental units for very low-income and extremely low-income tenants.132 Researchers Miriam Zuk and Karen Chapple of the Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley explain that “units may not filter at a rate that meets needs at the market’s peak, and the property may deteriorate too much to be habitable. Further, in many strong-market cities, changes in housing preferences have increased the desirability of older, architecturally significant property, essentially disrupting the filtering process.”133

Their analysis of the effects of market-rate construction on filtering show that in the Bay Area, roughly 1.5 percent of units filter down annually, meaning that they become newly occupied by lower-income households. They also point out that other research by economist Stuart Rosenthal of Syracuse University, which finds that rents on such units decline by only 0.3 percent per year,134 suggests that these lower-income households also take on a heightened housing cost burden.135

Conclusion

Housing is a basic need, fundamental to a healthy and stable life. All Californians should have the choice to stay rooted in their homes and communities, benefit from new investments and opportunities in their neighborhoods, and live without fear of unjust rent increases or eviction. But for too many renters in California, a safe, stable, and affordable home is out of reach. And still for others, housing is no longer an option. The hardships of unaffordable housing disrupt people’s health, education, and bonds with family and community. These consequences have most deeply impacted some of the groups who can least afford it: seniors, people with disabilities, low-wage workers, people of color, and families with children.

These challenges call for policy that stabilizes rents in the near term. In taking action to address the housing crisis, our policy goal must be first and foremost about people, not units. It must center on creating true belonging—structural inclusion where institutions and policies meet and are responsive to people's needs. Rent control policies can lay a foundation for this goal by providing a cost-effective, immediate, and widespread effect of stabilizing rents. They would have broad benefits, making more of tenants’ incomes available to be spent on other necessities, reducing traffic, freeing up public resources for other priorities, and increasing the stability and cohesion of neighborhood communities.

Other strategies to resolve the housing crisis— producing more housing, preserving existing affordable housing, removing barriers to racial integration—are essential, but they are long-term solutions. Without rent control, their benefits will not manifest until long after much of the harm caused by the broken housing market has been done. Only rent control can provide an immediate solution to the growing housing cost burden on renters.

This moment demands a public response today to correct for the failures of the current market, reduce the cost burden on renters, prevent further displacement, and balance fairness between tenants and homeowners. A significant part of the cost of housing being charged to tenants, and collected by landlords, is not due to any investment or action by landlords. Costs have increased in part because of public actions that improve neighborhood safety, air quality, school quality, and other qualities of life that increase property values. Because public action creates value, government has a legitimate responsibility to limit how much of it translates to increased rental costs.

Current law in California sets strict limits on rent control policies, restricting the possibilities for stabilizing rents in the state. These limits, such as exempting all singlefamily homes and all housing units built within the last forty years in California’s largest cities, or twenty four years in the rest of the state, remove an important policy tool for local, county, and state governments and voters to consider. Furthermore, they hinder our collective ability to imagine and advance a future that is only possible through greater affordability for all.

- 1Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society and Latino Decisions (December 2017) “California Survey on Othering and Belonging.” Statewide survey of California adults, n=2440.

- 2Anderson, Alissa and Sara Kimberlin (2017) “New Census Figures Show that 1 in 5 Californians Struggle to Get By.” California Budget and Policy Center. Accessed at https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/new-census-figures-show-1-5-calif….

- 3US Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey One-Year Estimates, Table B25074.

- 4US Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey One-Year Estimates, Tables B25074 and B25070.

- 5California Employment Development Department (2018). Occupational Employment Statistics, 2017. Accessed at https://data.edd.ca.gov/Wages/Occupational-Employment-Statistics-OES-/p…

- 6National Low Income Housing Coalition (2018), Out of Reach: The High Cost of Housing. Accessed at http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/OOR_2018.pdf. Note: This analysis is based upon $1,699 as the fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in California. NLIHC explains that fair market rent (FMR) is determined annually by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development: “For each FMR area, a base rent is typically set at the 40th percentile of adjusted standard quality two bedroom gross rents from the fiveyear American Community Survey… HUD finds that two-bedroom rental units are the most common and the most reliable to survey, so two-bedroom units are utilized as the primary FMR estimate.”

- 7Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (2017). Displacement Brief. Accessed at http://barhii.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/BARHII-Displacement-Brief….

- 8Ibid.

- 9Ibid.

- 10U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development (December 2017). Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Accessed at https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2017-AHARPart-1.pdf. Note: HUD defines a sheltered homeless person as an individual residing an emergency shelter or transitional or supporting housing for homeless persons who originally came from the streets or emergency shelters. HUD considers a person to be unsheltered if they reside in a place not meant for human habitation, such as cars, parks, sidewalks, abandoned buildings, or on the street.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Glynn, Chris & Emily Fox (July 2017). “Dynamics of Homelessness in Urban America.” as cited by Chris Glynn & Melissa Allison (August 2017). “Rising Rents Mean Larger Homeless Population.” Zillow Research. Accessed at https://www.zillow.com/research/rentslarger-homeless-population-16124/.

- 13Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, National Low Income Housing Coalition, and National Alliance to End Homelessness (April 2017). “Proposal to Foster Economic Growth: Submitted to the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs.” Accessed at https://www.responsiblelending.org/sites/default/files/nodes/files/rese…

- 14PolicyLink (2017). “When Renters Rise, Cities Thrive.” California #RenterWeekofAction. Analysis from The National Equity Atlas. Source: 2015 American Community Survey Five-Year estimates microdata from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS).

- 15Schildt, Chris (November 2017). Regional Resegregation: Reflections on Race, Class, and Power in Bay Area Suburbs. Urban Habitat. Accessed at http://urbanhabitat.org/sites/default/files/%20UH%20Discussion%20Paper%…

- 16Larrimore, Jeff, and Jenny Schuetz (2017). "Assessing the Severity of Rent Burden on Low-Income Families," FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 22, 2017, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2111

- 17Haurina, Donald R. and David Brasington (1996). “School Quality and Real House Prices: Inter- and Intra-metropolitan Effects”. Journal of Housing Economics, 5(4), pp. 351- 368.

- 18Smith, V. Kerry and Ju-Chin Huang, "Can Markets Value Air Quality? A Meta-Analysis of Hedonic Property Value Models," Journal of Political Economy 103(1), pp. 209-227

- 19Pope D.G., Pope J.C. (2012). “Crime and property values: Evidence from the 1990s crime drop.” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 42 (1-2), pp. 177-188

- 20Heckert, Megan and Jeremy Mennis (2012). “The Economic Impact of Greening Urban Vacant Land: A Spatial Difference-In-Differences Analysis.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(12), pp. 3010-3027.

- 21Birkenfeld v. City of Berkeley , California Supreme Court, 17 Cal.3d 129 (1976). For a discussion of relevant legal cases, see Baar, Ken, Patrick Burns and Daniel Flaming (2016) City of San José ARO Research to Support 2016 Updates to the Rent Stabilization Regulations. April 16, 2016.

- 22Gilderbloom, John and Richard Appelbaum (1988) Rethinking Rental Housing. Temple University Press, pp 134 - 135; Gilderbloom, John I., and Lin Ye. 2007. “Thirty Years of Rent Control: A Survey of New Jersey Cities.” Journal of Urban Affairs, 29(2), pp. 207– 220.

- 23California Department of Housing and Community Development (February 2018). California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities. Accessed at http://www.hcd.ca.gov/policy-research/plans-reports/docs/SHA_Final_Comb…

- 24McKinsey Global Institute (2016). A tool kit to close California’s housing gap: 3.5 million homes by 2025. Accessed at https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/Urbanizat….

- 25U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2016 One-Year Estimates, Table B25058.

- 26California Department of Housing and Community Development (February 2018). California’s Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities. Accessed at http://www.hcd.ca.gov/policy-research/plans-reports/docs/SHA_Final_Comb…

- 27National Low Income Housing Coalition (2018), Out of Reach: The High Cost of Housing. Accessed at http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/OOR_2018.pdf. Fair market rent is estimated at $1,699 for a two-bedroom apartment. NLIHC explains that fair market rent (FMR) is determined annually by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development: “For each FMR area, a base rent is typically set at the 40th percentile of adjusted standard quality two bedroom gross rents from the five-year American Community Survey… HUD finds that two-bedroom rental units are the most common and the most reliable to survey, so two-bedroom units are utilized as the primary FMR estimate.

- 28US Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey One-Year Estimates, Table B25074.

- 29US Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey One-Year Estimates, Tables B25074 and B25070.

- 30California Employment Development Department (2018). Occupational Employment Statistics, 2017. Accessed at https://data.edd.ca.gov/Wages/Occupational-Employment-Statistics-OES-/p….

- 31National Low Income Housing Coalition (2018), Out of Reach: California. Accessed at http://nlihc.org/oor/california.

- 32California Employment Development Department (2018). Occupational Employment Statistics, 2017. Accessed at https://data.edd.ca.gov/Wages/Occupational-Employment-Statistics-OES-/p…

- 33Ibid.

- 34California Housing Partnership Corporation (March 2018). “California’s Housing Emergency: State Leaders Must Immediately Reinvest in Affordable Homes.

- 35National Low Income Housing Coalition (2018), Out of Reach: The High Cost of Housing. Accessed at http://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/oor/OOR_2018.pdf. Note: This analysis is based upon $1,699 as the fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in California.