Work for justice and liberation requires the inclusion of arts and culture. The Haas Institute’s Notes on A Cultural Strategy report outlines a cultural strategy for belonging that centers the leadership, voices, storytelling, practices, and knowledge of people and communities who are marginalized in our society. It offers resources, evidence, case studies, and a workshop module for cultural strategies that are rooted in the Haas Institute's Othering & Belonging framework as well as in many successful models of activism and organizing.

Aimed at storytellers, artists, organizers, cultural strategists, funders, and other collaborators who are working to develop cultural strategies alone or as part of organizations and movements, this report offers notes and ideas on how cultural strategies can be developed for the greatest impact.

Like many cultural strategy practices, Notes on a Cultural Strategy for Belonging doesn’t fit well into one box–it is a bit theory, a bit case study, a bit recommendation, and a bit workshop. It outlines a what, how, and why of a cultural strategy for belonging, while also looking to next steps.

Download a PDF of the report here.

Foreword

Author, cultural critic, and feminist bell hooks, with john powell at the inaugural Othering & Belonging Conference, 2015. Photo by Eric Arnold.

from director john a. powell

Philosopher and friend Iris Young famously identified five major “faces of oppression” that thwart our efforts in advancing justice and fairness. Of the five possible overarching themes of oppression she identified, including exploitation, powerlessness, and violence, one of the five was culture. Culture, she argued, is one of the five primary, foundational forces that can be utilized against people. When a dominant group of people want to subordinate or control another group, one of the first things they do is try to take away peoples’ language, their religion, their food—in other words, their culture. And they work to enforce that of the dominant culture as the “norm.”

Culture is essential to our survival. It is not an overstatement for me to say that I would not be where I am today without having access to music. The music of Nina Simone and John Coltrane enabled me to get through my undergraduate experience as a black student in a predominantly white institution. Music was where I went to experience and find belonging in a place where I didn’t experience it through a variety of signals and structures.

Culture plays a vital role in understanding what it means to be human and our particularly human needs. Culture does not just talk to the conscious, it feeds the spirit. We are meaning-making, spiritual animals, and the spiritual part is transmitted through culture. Culture has taught us the power of seeing ourselves interconnected in a web of mutuality, as Dr. King put it.

Our interconnection is a key element for understanding culture and its power as culture is a deeply social experience. The ability to tell stories and create collectively is what scientists believe allowed our species, homo sapiens, to evolve. Stories and myths helped give us a new self and create new relationships as we built cooperation across thousands of people, rather than small or singular tribes.

Culture and art speak to the conscious and the subconscious. It helps us unite the heart and the mind. The information that culture transmits moves extremely fast, largely in ways we are not aware of. Culture signals in a way that is direct and experiential. And culture is in constant movement and interaction with us all, whether we recognize it or not. It’s a foundational part of how we make meaning as human beings. And what this report does is attempt to name and expand our understanding of how we can utilize culture as a site of change, as author Evan Bissell explains.

Culture is neither purely positive or negative. Too much of the world has been organized around a belief in the ideology of whiteness, with the need to dominate and control. This expression of whiteness is at its most foundational not a material belief, it’s about culture. For too long the story of whiteness has been a story about being special, about individualism and separation—being separated from God, from nature, and even oneself. And a central component of the story of whiteness has also been about fear. So it lives in constant anxiety. But while the ideology of whiteness is a myth, the belief in it produces real outcomes that affect everyday lives.

So we need new stories. Stories where people who are not white heterosexual men don’t show up as less than, as the “other.” Stories that reject a re-assertion of an idea that who belongs should be organized around race, blood, or phenotype.

Culture can move people in a way that policies cannot. People largely organize themselves and operate around stories and beliefs, not around facts. And they organize more around love and belonging than shame and fear. So in constructing our new we, we need to be careful not to replicate ways of what I call breaking.

Building a culture of belonging is not the same as simply removing barriers. We must also organize our spaces, our structures, and our policies to do the work we need to build the world we want to live in. We have to work together to build a well-developed ecosystem that supports our work. We need research and analysis, we need inclusive narratives, and we need organizing, which is about building power. And we need all these things activated and in alignment—and all of these move through culture.

Developing our new story will take a lot of work. As illustrated in this report, there are many rich cultural histories to learn from as well as many emergent expressions to which we can look to for inspiration and aspiration. These Notes delve into the ways that artists, culturemakers, and community leaders are anchoring work in cultural expressions that celebrate our differences and provides models on how arts and culture can create space for more fully realizing that which we share.

A culture of belonging recognizes that we are always in a state of dynamic action and reaction. Belonging is never done and will constantly have to be remade. We’re in the midst of constructing new ways to see and new ways to be. This is not always comfortable, but it is part of our human experience.

As we move forward together in this time of rapid and concentrated change, the work of arts and culture will play a major role in how we lean into a future that says to everyone: You belong. We hope this report will provide some ideas for understanding some of the vital and visionary aspects of a cultural strategy for belonging.

Introduction

Culture and Belonging

In the weeks leading up to the pivotal midterm elections in 2018, young organizers in contested districts in California were finalizing details of unconventional Get Out The Vote actions through a program called the Cultural Ambassadors Fellowship.1 In Fresno, Jazz Diaz, who was one of the program’s Fellows, made paper by hand and embedded the seeds of flowers that grow on both sides of the US/Mexico border within it. She was working with Fellow Yenedit Valencia to host a workshop that was part printmaking and part traditional Oaxaqueño dance. The resulting notes and prints on the seed paper were then shared with new voters by door-to-door canvassers with the youth organization 99Rootz.

Meanwhile in Orange County, fellow ambassadors Jesus Santana and Alba Piedra were finalizing a workshop activity about flags and their relationship to land and identity. In this workshop participants created flags that represented visions of a just and equitable California, which then became the basis for voter information pamphlets to be used by young Get Out the Vote canvassers working with the organization Resilience Orange County. And on the outside of a free election day shuttle van, fellows Yacub Hussein and Haadi Mohamed completed images that connected the story of contemporary San Diego immigrants with those of civil rights and farmworker organizers from a half century before. With the group Partnership for the Advancement of New Americans, Yacub and Haadi drove members of their neighborhood to the polls who had indicated they otherwise might not have been able to get there. This work connected them to a history of community organizing and leadership that continually expands our notions of who belongs.

These projects, organized with the group Power California, were part of a larger umbrella of efforts from the Haas Institute’s Blueprint for Belonging (B4B) program, which works to develop and expand narratives in California that are more reflective of the state’s diverse demographic makeup. Their approach is driven by the foundational othering and belonging framework of the Haas Institute, which understands that creating a more fair and inclusive society requires engaging culture as a critical component of transforming systems and social narratives. Organizers and artists ground their visions of belonging in cultural roots, practices, and frames, and then use this grounding to create processes that reflected belonging while mobilizing new and underrepresented voters. As the Cultural Group wrote, “We change culture through culture. That means that culture is both the agent of change and the object of change.”2

In a foundational article called The Problem of Othering, the Haas Institute’s john a. powell and Stephen Menendian describe belonging as, “An unwavering commitment to not simply tolerating and respecting difference but to ensuring that all people are welcome and feel that they belong in the society.”3 They continue that this, “must be more than expressive; it must be institutionalized as well.”4 A culture of belonging must inhabit stories, symbols, and how we see ourselves and each other. It also must inhabit the systems, policies and practices of society that make up the substance of culture.5

The transformative potential of working towards a culture of belonging lies in the details. As journalist and critic Masha Gessen notes, a favorite strategy of fascist leaders is the weaponization of narrow definitions of cultural belonging along lines of race and ethnicity.6 Class, gender, sexuality, and ability have all been and are still being weaponized and manipulated in similar ways. This is the opposite of belonging, this is othering. This othering happens at multiple scales–national, religious, neighborhood, identity, and more. Across the political spectrum, from the work of the Culture Group7 to writer/provocateur Andrew Breitbart8 , the argument has been made that culture is an essential and sticky site of change.

It is not enough to just ask, to what end are we creating a culture of belonging? We must also ask: Who belongs? How is belonging created? What are we seeking to belong to? How are we participating in advancing or narrowing that belonging? Identifying, amplifying and cultivating aspects of culture that make real a world in which many worlds fit9 , is the seed of cultural strategy.

Oaxacan dance workshop in Sanger, California. This was one part of a Cultural Ambassadors Get Out The Vote project led by 99Rootz fellows Yenedit Valencia and Jazz Diaz. Photo by Pacita Rudder, 2018.

A Cultural Strategy for Belonging

While cultural strategy has long existed and in numerous forms, there has been more focused contributions in recent years to name, guide, and expand on the work. In a report commissioned by Power California, Cultural Strategy: An Introduction and Primer (2019), author Nayantara Sen defined cultural strategy as, “A field of practice and learning which engages all aspects of cultural life and all avenues of social change making to transform society for a just, viable, and liberatory future.”10

Building on this definition, a cultural strategy for belonging centers the leadership, voices, storytelling, practices, and knowledge of people and communities who have been the target of oppressive ideologies and systems. A cultural strategy for belonging shifts whose knowledge and vision is made actionable in reshaping society. This grows the cultural power of those dehumanized and delegitimated towards the creation of insistently human belonging, justice, and liberation.

Valuing oneself, one’s culture, and one’s community, even in the face of violent negation and devaluation, is at the core of a cultural strategy for belonging. As Yenedit Valencia shared, “I feel that once we know where we come from, where our parents come from, what language we speak, what are our cultural practices, our values, there is no going back…once you know who you are, there’s just no going back.”

Forged through love, resistance, survival, joy, and continuity, these acts complicate, disrupt, and transform narrow conceptions of who belongs that are defined through exclusion and othering. Audre Lorde wrote, “As a Black lesbian mother in an interracial marriage, there was usually some part of me guaranteed to offend everybody’s comfortable prejudices of who I should be. That is how I learned if I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”11 Working towards a culture of belonging means celebrating and supporting Lorde’s self-definition, while working to abolish the violence she names. A cultural strategy for belonging creates the conditions and infrastructure to cultivate, amplify, and connect these stories and practices in the midst of continued othering.

A 2019 Othering & Belonging conference attendee reads through the map of places of belonging created by Haas Institute Artist in Residence Christine Wong Yap and dozens of conference attendees. Photo by Eric Arnold.

Underpinnings of a Cultural Strategy for Belonging

This report responds to and builds off the work of many others and the influences that underpin it are wide-ranging. What follows is a rough and incomplete inventory of traces that make up influences and practices of cultural strategy. Much of this work is relational and based in over a decade of work with sectoral trespassers. Paramount are the hybrid practices of people from whom I have learned directly, including Gina Athena Ulysse, Brett Cook, Una Osato, Julia Steele Allen, Morgan Bassichis, Jenny Lee, Nate Mullen, Dania Cabello, Ora Wise, and Roberto Bedoya. It also includes spaces like the Allied Media Conference and Creative Wildfire, hosted by Movement Generation.

A variety of written works have also provided a theoretical grounding. Paolo Freire and bell hooks’ collection of works on pedagogy play a central role in guiding the approach to practice. Robin D.G. Kelley’s Freedom Dreams explores the tradition of the Black Radical Imagination, raising essential questions about how cultural practice and cultural resistance is entangled with positionality, history, and other efforts of radical social change. Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderlands/La Frontera is a formally mixed-genre approach to theory that challenges notions of expertise and frames identity and culture as key sites of resistance. Audre Lorde’s collection of essays and poems Sister Outsider broadens the lens of analysis within the context of Black feminisms and crystallizes the power inherent in cultural and artistic work. Winona LaDuke’s Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming chronicles Native American efforts to reclaim sacred cultural elements and their relationship to place to illuminate the deep importance of culture as a site of change. Edward Said’s Orientalism, is a historical analysis of the role of cultural production in orientalism and colonialism, building off of frameworks of hegemony formulated by Antonio Gramsci in the Prison Notebooks.

Efforts to clarify what cultural strategy is, and what it is not, can be drawn from a number of works and activities. The Principles of Media-Based Organizing are central to the 20-year efforts of Allied Media Projects to center a wide definition of media-making in radical social change. EastSide Arts Alliance is an important standard within the Bay Area, carrying their work with a consistency and continuity that reflects a long-term praxis. The work of CultureStrike (now the Center for Cultural Power) features centrally within this field, including their 2019 concept paper, Culture is Power. In Making Waves (2014), the Culture Group laid out a foundational argument for cultural strategy as named, drawing on historical examples and emphasizing the essential role of culture in social change. The aforementioned Cultural Strategy: An Introduction and Primer by Nayantara Sen is an excellent illumination of cultural strategy, offering a layered and detailed framework for funders, cultural strategists, and organizational leaders.

Another thread of works focus on arts-based and cultural organizing tactics that contribute to the “how” of discrete project implementation and development. Cultural Tactics (2016) by the Design Studio for Social Innovation offers three cultural tactics derived from their projects. The Center for Artistic Activism website hosts a variety of tools, interviews and materials that explore the intersection points of art and activism and how to strengthen these to deliver “aeffect” (a combination of affect and effect). Beautiful Trouble also offers a catalogue of online resources to support practitioners. This is hardly an exhaustive review.

This report is also informed by the Haas Institute’s guiding framework of othering and belonging. This framework views culture as a core element of the work of remediating othering and advancing belonging. Many of the cultural strategy projects and characteristics explored here come through the practices and a growing infrastructure at the Institute infusing arts and cultural strategy. In this work, the Haas Institute leverages its cross-sector and interdisciplinary nature to host diverse and varied convenings, research projects, fellowships, and multimedia platforms that deeply integrate arts and culture. This report responds to those efforts, learnings from staff workshops on cultural strategy, and is created in close partnership with my colleague Rachelle Galloway-Popotas.

Where this paper is going

This paper is for storytellers, artists, organizers, cultural strategists, producers, funders, and collaborators who are working to develop cultural strategy with intention and rigor to increase impact. It is primarily meant for people who have some experience in the field as a way to deepen these efforts.

Like many cultural strategy practices, Notes on a Cultural Strategy for Belonging doesn’t fit well into one box–it is a bit theory, a bit case study, a bit recommendation, and a bit workshop. It outlines a what, how, and why of a cultural strategy for belonging, while also looking to next steps.

In the first section, I detail attributes (WHAT) and practices (HOW) of a cultural strategy for belonging. In the second section, I look at WHY a cultural strategy for belonging works to create a more authentic and expansive belonging. This section focuses on the dynamic and everyday nature of culture, as well as the unique way that cultural strategy catalyzes change despite highly unequal economic, political, and social power. In the third section, I look to next steps. I outline three guideposts that can help to avoid cultural strategy staying only in the symbolic realm of change and how to build a stronger infrastructure for our work. Next, I offer recommendations for funders, researchers, and organizational leaders. Finally, I present a workshop derived from previous collaborations with organizers, activists, policy advocates, and researchers to develop creative cultural strategy approaches to their work.

What and How - Attributes and Essential Practices

In the work of social, economic, and cultural transformation, what are the unique attributes of a cultural strategy for belonging? How are these attributes made real in practice? As an artist, researcher, organizer and educator engaged in cultural strategy, I seek to create processes that access what the surrealist, anti-colonial writer Aimé Césaire called “poetic knowledge” or “experience as a whole”.12 This is essential for expanding our collective, sustainable efforts towards justice and belonging through insisting on the inherent humanity of all people and concern for the earth and all living creatures. Cultural strategy can–and should–expand our epistemology by making knowledge that is generally excluded from social change, essential to research, advocacy, organizing, and living. This knowledge is frequently delegitimated because of who is producing it–queer people, poor people, Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color, people with disabilities–or the form it takes–folk knowledge, family stories, belief systems, songs, experiences, emotions and expressions. In the opening lines of the essay Poetry is not a Luxury, Audre Lorde explored how the quality of analysis that comes from poetic knowledge is essential:

“The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless-about to be birthed, but already felt.”13

The attributes of a cultural strategy for belonging can shift the quality of our analysis. This changes the possibilities and boundaries of belonging through new forms of scrutiny, research, and creation. This bears on both the process and outcomes of social change efforts.

Attributes of a Cultural Strategy for Belonging

The following 12 attributes of cultural strategy are a palette. These attributes clarify the unique contributions of a cultural strategy for belonging. They can also guide the development of cultural strategy projects. At a minimum, these can be assessed against the needs of a project that is looking to integrate cultural strategy. Ideally, this assessment occurs early in the analysis of a need or problem as a way to shift the “quality of light” of analysis. Each attribute is generated from an analysis of case studies of our work at the Haas Institute, as well as art and cultural projects that have inspired this work.

For a workshop on working with these and additional examples related to each attribute see the Appendix.

1. Insisting on humanness

James Baldwin wrote, “The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.”14 When the forms and functions of this world are defined by profit, violence, consolidation of power and othering, we are left with a dwelling place at the edge of collapse, one where humanness is narrowly defined and widely delegitimated.

The vulnerability, subjectivity, fragility, and sacredness of an insistence on the dignity and humanity of all people undergirds an authentic belonging. Politics, research, and law can lack the agility to convey or acknowledge the complexity of this humanness. Humanness makes things complicated, imperfect, and slower. Without attention to all of these parts, we stand the risk of creating limited solutions that force us to exclude parts of our selves or our communities in pursuing statistics that reflect progress. For example, the push for prison reform for “good” criminals is predicated on a solidifying of the image of “bad” criminals, flattening their humanity and the history that has produced the prison system. People don’t identify or see themselves in statistical terms or a politically convenient dataset—art and cultural strategy can keep our work insistently human, which means we are strengthening belonging through process and outcome over the long-term. People see themselves in the work and so they return–again and again. This focus on our shared humanity adds urgency and relevance to campaigns and narrative change efforts.

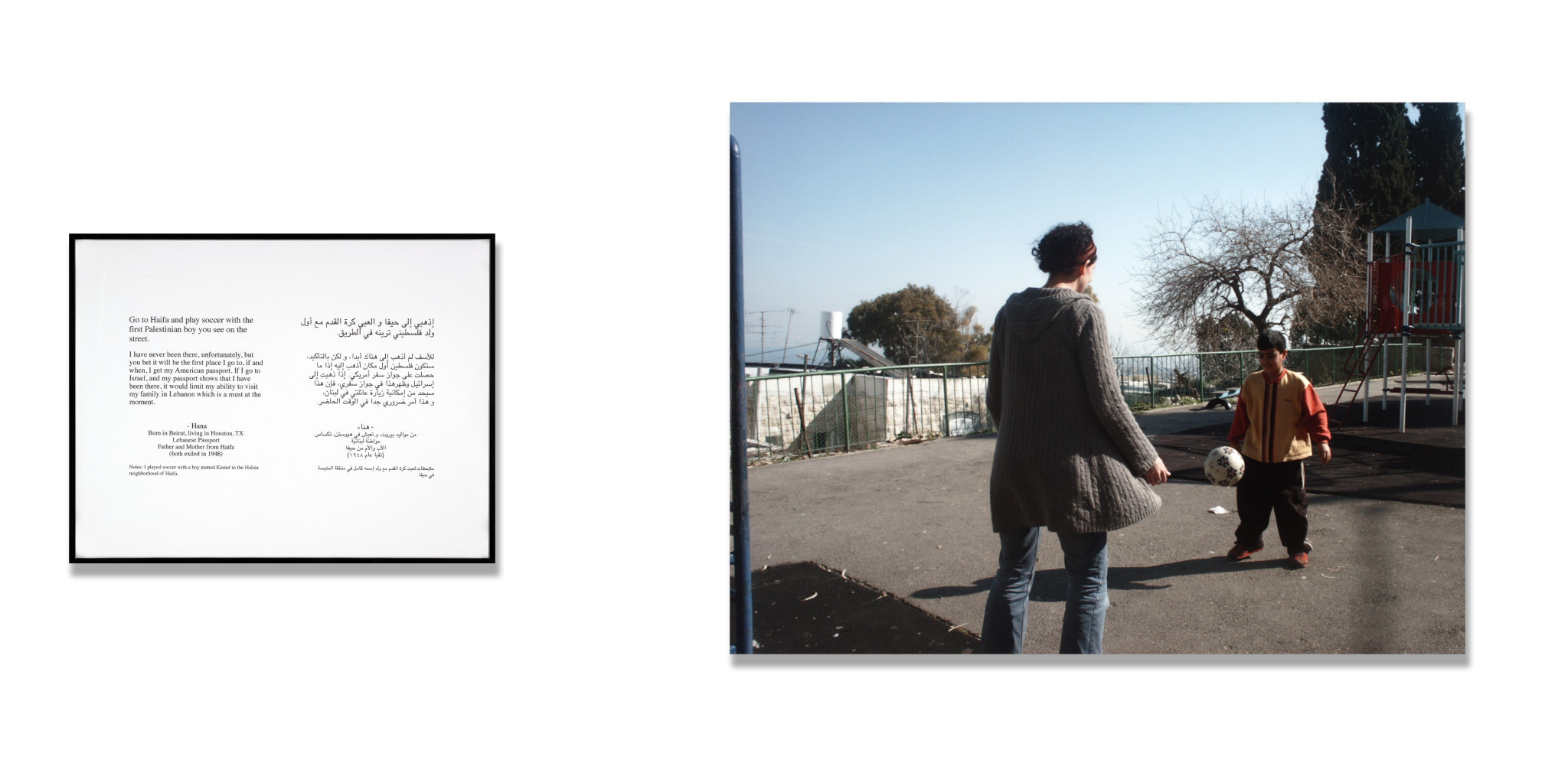

Emily Jacir, Where We Come From (Hana), 2001-2003. Chromogenic print and laser print mounted on board; variable San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase © Emily Jacir

WHERE WE COME FROM

Emily Jacir

Born in Palestine and holding a US passport, Jacir used the power of movement afforded by her citizenship to perform simple, intimate tasks for Palestinians living in exile. She asked Palestinian people in exile, “If I could do anything in Palestine for you, what would it be?” Jacir then carried out these actions and documented them with simple snapshots. Here, she was asked to, “Go to Haifa and play soccer with the first Palestinian boy you see on the street.” The work uses these intimate exchanges to bring an intractable global political issue down to the level of human longing and connection–and reveals the power of her US citizenship as well. The acts are not overtly political, but they reveal, in very human ways, the disruptions of life that come from displacement through colonization.

Prologue

Based on the Gary family story, 1952

Dear Ciera,

We write this with a longing heart

the journey you are embarking on

is one of horrific tradition

and our life is your testimony

is your roadmap to justice

is your proof of the matter.

We write because we admire the stories

unfolding amongst these pages,

you might call us blown away

by their honesty and the fact

that the fight has yet to cease

in this beloved city.

Listen, Richmond was the home

we fought the hardest for.

We made a home in between Kaiser shipyards and a war zone,

one Black house on an all white block.

Against ghostly men,

out for Black blood, we,

a mass of races gathered

weaving together our place of refuge

and now we pass the torch

through this letter.

If you stand your ground long enough,

you might see the shadow of the cross burning

on our lawn, as it fades away.

Don’t grow weary.

This story is merely a symbol, a note,

perhaps a scriptures all the more,

saying that this too

shall pass.

WALKING TESTIMONIES

Ciera-Jevae Gordon

In a Richmond, California city council meeting in 2015, a councilmember who opposed rent control implored the audience to not listen to the few dozen community-member testimonies that were shared that evening. Instead he asked the public to pay attention to the facts that he had presented as the only valid form of expertise in deciding how the policy should be evaluated. In response to this and other dominant narratives around housing challenges in Richmond, the Staying Power Fellowship was formed, a cultural strategy project focused on housing and belonging in Richmond, co-created by the Haas Institute together with community members in Richmond and three local organizations. Out of that program a cohort of Richmond-based fellows developed a series of poems based on interviews with residents who had been impacted by the housing crisis. These poems were read at city council meetings and housing workshops throughout the city. In one piece, Staying Power fellow DeAndre Evans, referring to data presented on housing displacement in Richmond, posed the question: “How many of us aren’t statistics?” A selection of the poems was compiled together with visuals and facts about the history of housing injustice and published in a booklet entitled Walking Testimonials (see excerpt on this page). This work serves as an urgent reminder, rendered through culture, that the question of housing can’t only be encapsulated in statistics and surveys–it includes histories of place, words, smells, sounds, temperature. The book of poems was distributed alongside an accompanying research and policy report published by the Haas Institute. By giving equal footing to resident stories and experiences, the project insists on a human frame, which gives texture, complexity, nuance, and power to a vision of belonging, particularly when one’s ability to be seen as human and as belonging has been systematically denied.

2. Reclaiming cultural memory

At a conference on housing justice in 2019, scholar Laura Pulido articulated the importance of understanding a “cultural memory of erasure” as an element of organizing history.15 Reclaiming cultural memory provides strength, sustenance, and vision. It also produces an archive of injustice that can help orient and ground requirements that would make structural belonging real. In the Bay Area, Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is an organization led by urban Indigenous women. While reclaiming and returning Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone land to Indigenous stewardship, it also acts to powerfully underscore the reality of contemporary Ohlone presence and combats the erasure of Ohlone history as the first inhabitants of that land. Artists frequently act as alternative historians in compelling and transformative ways that create spaces for learning about these histories, such as Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum: From Slavery to Mass Incarceration and National Memorial for Peace and Justice (focused on racial terror lynchings) or Dread Scott’s 2019 reenactment of the largest slave revolt in US history through a multi-year community-based process.

Photo by Stevie Sanchez, EastSide Arts Alliance

MALCOLM X JAZZ FESTIVAL

EastSide Arts Alliance is a cultural center rooted in the San Antonio neighborhood of Oakland that hosts hundreds of events each year, classes, as well as other cultural, political and arts programming. For the past 20 years, the center has hosted the Malcolm X Jazz Festival in nearby San Antonio park. The festival celebrates diverse elements of Black cultural production and their relationship to liberation struggles over time. The work expands popular understanding of the contributions and legacy of Malcolm X as well, who saw culture as, “an indispensable weapon in the freedom struggle,” and that “we must recapture our heritage and identity if we are ever to liberate ourselves and break the bonds of White supremacy.” The festival reframes and grounds the cultural heritage, identity and legacy of jazz, blues, and hip-hop and cultural production more broadly as an essential element of Black liberation, while creating a yearly, positive gathering space for the San Antonio Neighborhood and Oakland more broadly.

3. Articulating and validating alternative and marginalized value systems and ways of knowing

Against Euro-American attempts of Native genocide and slavery and plantation system, Native people and enslaved Africans used ritual, culture, and art to reaffirm systems of value that articulated belonging–to the earth, to history, to each other, and to collective futures. Cultural theorist and writer Sylvia Wynter frames how rituals and dance served as ways to reestablish human connection to earth against the extractive plantation system.16 Across numerous colonial contexts—Maori healing practices in New Zealand, Candomblé in Brazil, and the Sun Dance across North America—ritual practices were banned, reflecting the power that they had to disrupt and reject colonial narratives and practices aimed at their dehumanization. Practices like these continue to emerge and produce radically different visions of value and belonging despite the presence of violent, dominant value systems.

Gathering, Mount Mackay, Fort William First Nations, Thunder Bay, Ontario, 1992 Photo: Michael Beynon. Image Courtesy of the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity

AYUMEE-AAWACH OOMAMA-MOWAN/SPEAKING TO THE THEIR MOTHER

Rebecca Belmore

Anishnibekwe artist Rebecca Belmore’s sculptural work–a larger-than-life megaphone–creates the opportunity for witnessing and participating in alternative forms of communication and knowledge through inviting First Nations people to speak with the earth. Installed at different locations, the megaphone reorients forms of communication and the framing on who/what is able to communicate. Represented in this work, the curator and writer Jen Budney pinpoints the importance of speaking and listening to country/land/earth in Indigenous communities and how this is reflected in ritual and artistic practice.17 The work shifts human relationship to the land as one of dialogue rather than ownership through use of ritual and symbol.

4. Shifting and democratizing concepts of expertise

In 1982, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five released The Message, one of the first rap hits. Though not with the language of public health researchers, in the song Flash speaks about the relationship of toxic stress to the social determinants of health. He raps, “The bill collectors, they ring my phone / And scare my wife when I’m not home / Got a bum education, double-digit inflation / Can’t take the train to the job, there’s a strike at the station / Neon King Kong standin’ on my back / Can’t stop to turn around, broke my sacroiliac / A mid-range migraine, cancered membrane...” It would take at least two decades for public health to begin seriously discussing these same ideas. While Flash may not have been invited to perform for the World Health Organization or publish his work in journals, his analysis and expertise was made public through music.

Building on the radical pedagogy of educator Paolo Freire, theater artist Augusto Boal developed theater exercises and forms that sought a dialogic relationship between performers and audience, and used theater as a way to develop understanding of and action upon the world.18 Cultural strategy frequently subverts the traditional pathways to expertise, too often held through infrastructures and institutions built on systems of oppression. Art provides forums and mediums that can circumvent traditional rubrics of expertise, and entry points for more people to express their truths as valid contributions to our understanding of the world.

Climate Curious. Photo by Ghana Think Tank, 2017.

GHANA THINK TANK

The premise of Ghana Think Tank is simple: ask experts in the third world to solve problems in the first world. The infrastructure of the project flips historical and paternalistic development models on their head, reframing concepts of expertise and the need to take leadership from the global margins. In the project pictured below, GTT surveyed residents of Williamstown, Massachusetts about their concerns with global warming, and then shared those concerns with think tanks that GTT convened in countries already deeply impacted with the effects of global warming. These experts conducted a series of discussions and planning sessions to devise responses and recommendations. Many of the answers reflected the need for people in Massachusetts to lessen their global footprint as a way to create a sustainable planet. The photo here is based on advice from Moroccan experts who advised Williamstown residents to begin to search out new, sustainable food sources as cultivation of protein sources like beef get harder. In developing this practice, crickets were served at the gallery opening.

5. Trespassing across sectors and silos

Building on reflections made by the artist Rick Lowe about the potential for artists to be trespassers across many domains, scholar Shannon Jackson reminds that, “It is of course in that trespassing that art makes different zones of the social available for critical reflection.”19 Sectors, disciplines, issues, and other silos prevent us from accessing the holistic imperative that is central to belonging. Structures that reward a narrow version of success in academia, the nonprofit world, and much professional practice reinforce these silos. For artists and cultural workers, who have less entrenched structures of success (and rubrics of measurement), they have a unique ability to move between and across these divides. In their movement, artists and culturemakers create profound connections and potentialities. This trespassing requires attention to symbolic overlaps and a willingness to challenge normative approaches.

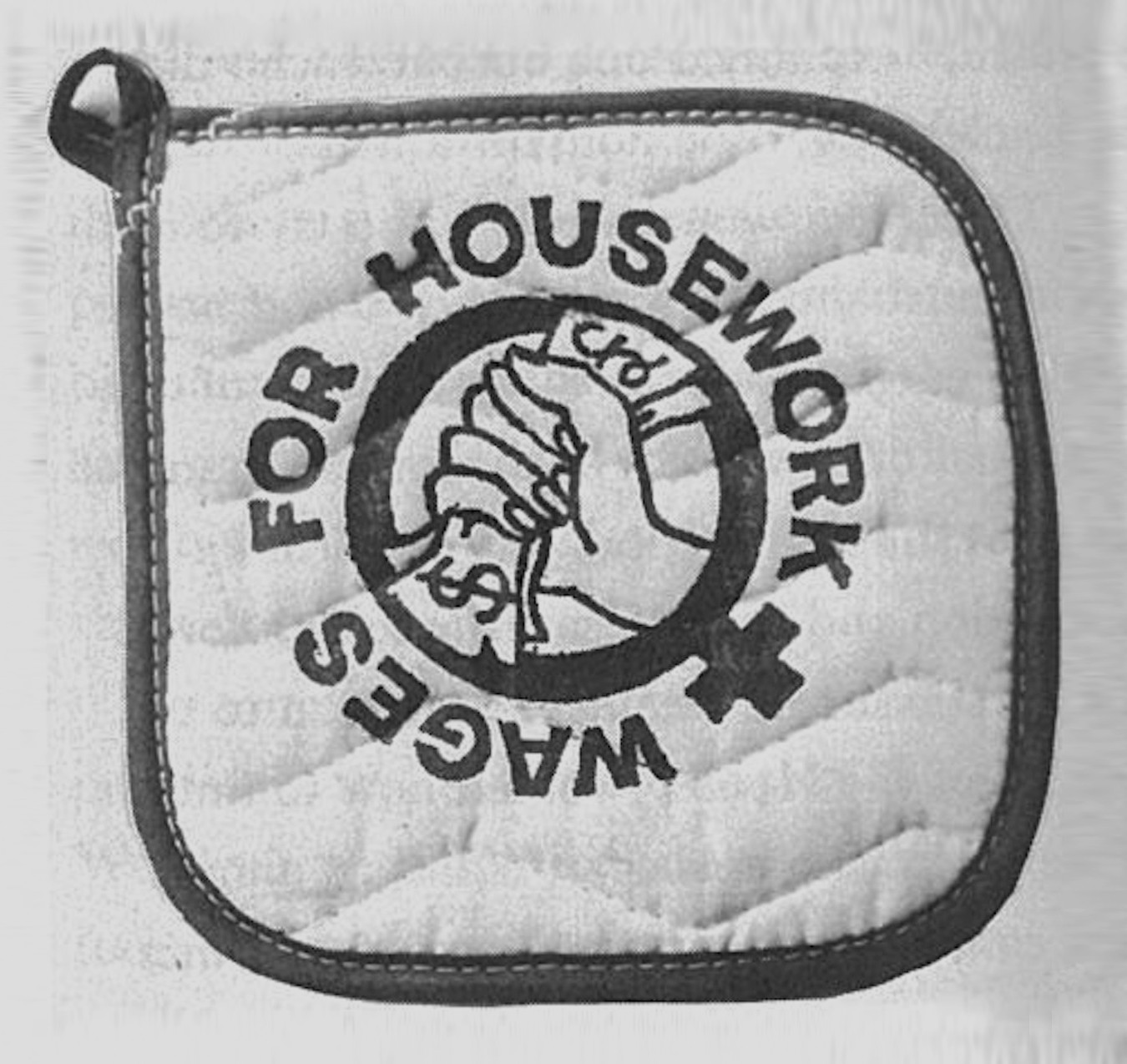

Potholder - Wages for Housework

WAGES FOR HOUSEWORK NY COMMITTEE

Though not an art project, the organizers of Wages for Housework (particularly the NY Committee) employed cultural strategies to advance their critique of the devaluation of women’s labor and the intersection of patriarchy and white supremacy. Through these processes they sought to revalue housework by bringing it into different frames of analysis. These techniques included the widely distributed zine Tap Dance, renting a Brooklyn storefront for public conversations and women drop-ins, selling Wages for Housework-themed potholders (pictured), and frequenting supermarkets and laundromats as the “shop floors” for home workers.

6. Bridging across divides and differences

In a Haas Institute paper she wrote on the role of mind science in narrative change, the Perception Institute’s Rachel Godsil notes that, “Our brain serves a social purpose, connecting us as creatures in a larger community through interwoven stories...Stories form the basis for empathy and for figuring out acceptable or unacceptable social behavior.”20 When art tells stories, it can bridge what may appear to be insurmountable interpersonal divides. Stories can transcend physical and material boundaries, including national borders, the walls of prisons or neighborhood dividing lines. Art can often create an infrastructure for the exchange of stories and experiences that would otherwise be impossible. For example, in La Piel de la Memoria, artists Suzanne Lacy and Pilar Riaño-Alcalá created a mobile museum on a bus that consisted of objects loaded with personal memories. The objects were collected from individuals living in different areas of a neighborhood that had experienced ongoing violence between them. The bus then traveled between the areas as a way to reflect the shared impact and stories of these communities. Stories like these strengthen connections within and across communities that are essential for building power, for healing, and for including stories of lives too often rendered invisible.

Post-show dialogue with members of WISDOM and the Prison Ministry Project in Madison, Wisconsin, April 2016. Courtesy of Julia Steele Allen.

MARIPOSA & THE SAINT

Julia Steele Allen

The play Mariposa & the Saint is an intimate look at solitary confinement. The play was developed by two friends who met through California Coalition for Women Prisoners as a way to help one of them through her time in solitary confinement. When the play was finished, the co-writers decided to use the play to support solitary confinement reform and abolition movements across the country. After each showing of the play, event organizers worked with local people in the place the play was performed to enter a dialogue, with the post-show conversation having equal time as the play. In many places, audiences were largely sympathetic, which strengthened local organizing bases, but didn’t bridge the conversation to people who weren’t already in favor of, or mobilized against solitary confinement.

As the tour continued, the organizers began to seek out relationships with audiences who were also family members or friends of their sympathetic audiences–legislators, judges, and students studying to become jail guards. These connections supported a second tour for audiences who weren’t immediately sympathetic to the work. The emotional power of the work allowed it to bridge the otherwise reactive political stance of many of its audiences and support the campaigns to reform/repeal solitary in places that otherwise were closed off to the issue.

7. Convening and connecting coalitions, movements, communities

Culture can provide wide and inclusive entry points. It can also provide an opportunity for gathering and can retain people in a process or project when other means might not. Even when people may not agree politically or ideologically, art can provide opportunities to work towards shared goals and understanding. For example, the People’s Kitchen Collective uses food as a medium to literally set tables for dialogue, convening, celebration, and organizing. For 20 years, the Allied Media Conference has used an expansive definition of media, and not a focus on issues, as the central organizing medium of the conference. This entry point has led to the launching of numerous national networks of ongoing political influence. In an interview, Civil Rights activist Dorothy Cotton described the movement as a, “singing movement” and shared a story about a young man dropping his work and jumping a fence to join a march (and the movement for the rest of his life) because he was so drawn by the music.21 Artistic and cultural projects can also be explicitly political, serving to provide unifying symbols and language, as with the visual work of Emory Douglas for the Black Panthers. Across many more contexts, art can function as connective tissue and a welcoming entry point.

REFORM

Pepón Osorio and the Bobcat Collective

reForm Fun Day at Fairhill, May 1st, 2015. Photo by Tony Rocco.

In 2013, Philadelphia closed 24 schools, including Fairhill Elementary in North Philadelphia. Osorio, an artist and professor at nearby Temple University wondered how the closure had affected the surrounding community (schools like Fairhill were planned at the center of neighborhoods) and slowly initiated a process of reconvening those connected to Fairhill. Over nearly three years, Osorio worked with a collective of teenage alumni and his Temple students to organize a series of public events including a Fairhill Fun Day (modeled on a school tradition) which reconvened 800 former students and employees for the first time since 2013 (pictured here), and a class reunion. The collective also spoke at public meetings and interviewed decision-makers and stakeholders about the closures. The project culminated in an installation that repurposed many of the materials left in the school and spurred on the efforts of the collective as they connect with related efforts around school closures in Puerto Rico.

8. Activating and provoking emotion

Perhaps the most commonly-held understanding of art’s impact and power is that it can spark emotions that range from joy to fear, sadness to rage, reverence to nourishment. This might be experienced intimately when reading a wrenching poem alone or, as was the practice of Martin Luther King, Jr. to call Mahalia Jackson on the phone to listen to her sing in times of his own despair. It might occur in public forms such as the 2014 People’s Climate March which included massive artistic production and coordination or in the joyful and inspired response to Ryan Coogler’s film Black Panther. The emotive and affective power of art is one of its most tenacious and compelling attributes, if not also one that is most subjectively experienced. For many, it’s not hard to imagine a poem, song, movie, painting, poster, or performance that has transformed how we see the world and turn to for energy, inspiration, a good cry or laugh.

GET ON BOARD LITTLE CHILDREN, THERE’S ROOM FOR MANY A MORE

Campo Santo

Kerner Commission at 50 Conference, organized by the Haas Institute, 2018. Performed by Campo Santo members Delina Patrice Brooks, Britney (Brit) Frazier, Ashley Smiley, Dezi Solèy. Text organized by Evan Bissell and Sean San José (Campo Santo). Photo by Serginho Roosblad.

A twenty-minute performance by the Bay Area theatre collective Campo Santo reading the text of the Kerner Commission and two other documents; W.E.B Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction and the policy platform from the Movement for Black Lives. The power and skill of the performers created a strong emotional connection to the three documents and provoked a standing ovation. The performance of the texts, the layering of the language and addition of elements of song and repetition revealed the ways that the artistic tools transported the written pieces that are primarily viewed through analytic lenses into an emotional, heart-space.

9. Disrupting the dominant worldview through interventions of worldviews from the margins

Disruptions of a dominant white supremacist worldview are an everyday occurrence. The impossibility of existing as an “Other” under a worldview that seeks to erase the “Other” makes these disruptions unavoidable and inevitable. In the context of poverty, anti-Black racism, and transphobia, these disruptions are met with especially dangerous and violent responses on the part of, or protected by, the state–responses that have catalyzed the Movement for Black Lives.

Recognizing the power of the margin for its radically different viewpoint and insisting on the value of oneself and worldview, artists and cultural producers have long held a role as critical interventionists. These critiques can be subversive, such as Goya revealing the degeneracy of the aristocracy in his royal portraits or Basquiat’s crowns on energetic and deconstructed figures. These interruptions can also be implicit in form, like Zora Neale Hurston rebuffing attempts to “clean up” her dialect-based writing or Gloria Anzaldua’s bilingual, genre bending text Borderlands/La Frontera. Disruptions of worldview can also be direct, as with Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds’ public remembrance of Native murder in Minneapolis or Code Pink’s citizen arrest of Henry Kissinger for war crimes. And they may also take the form of radical presence; as with Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s mytho-hybrid identity constructions or Greta Thunberg’s weekly climate strike protest outside the Swedish Parliament building. Importantly, these interventions don’t just disrupt, but simultaneously express and demonstrate radically different worldviews.

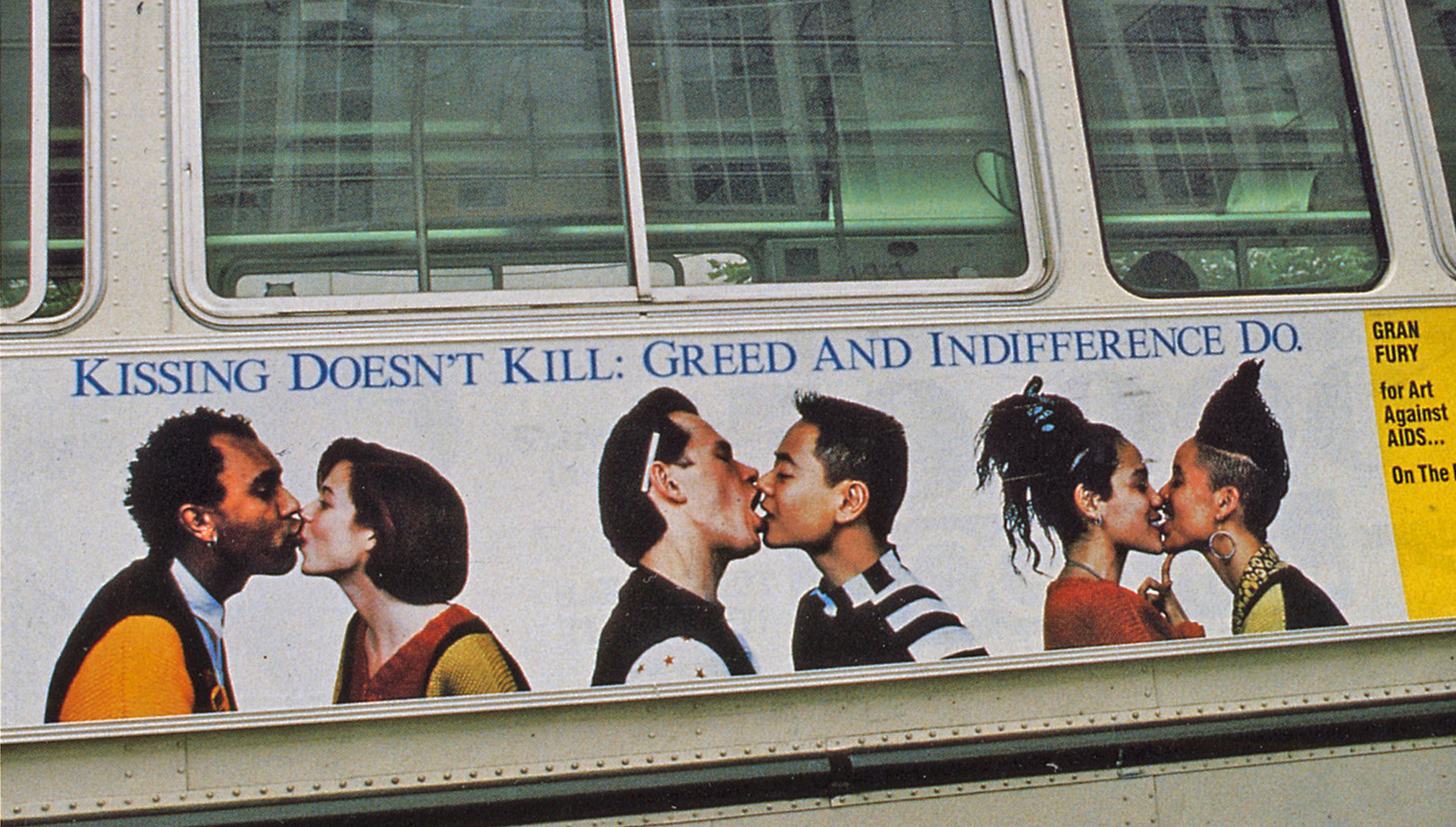

Gran Fury, Kissing Doesn’t Kill, Greed and Indifference Do (Muni Bus installation), ink on vinyl, 1990

POSTERS OF ACT UP

Gran Fury

In the midst of the AIDS crisis and government inaction, Gran Fury formed out of the direction action group ACT UP as an 11-person collective. It created a series of public works that directly raised the issue of homophobia,misogyny, and racism in the discussion of AIDS relief, while also celebrating different expressions of sexuality in direct ways. Its works challenged myths and narratives about the relationship between sexuality and AIDS, while also serving to raise the profile of LGBQ issues and presence. Alongside the bus ads (pictured on this page), the group created the iconic pink triangle symbol (as an inversion of the Nazi symbol for queer people), and numerous posters that offered scathing, witty, and emotional critiques of public officials, companies, and religious leaders who were blocking relief to people impacted by AIDS.

10. Building the space and means to imagine, play and envision alternatives

Equal to the ability of art to offer critical insight into dominant narratives and systems, is its ability to envision alternatives. Rachel Godsil writes that, “He who defines reality holds power.”22 For people excluded from social power, art and culture are forms of power that allows one to redefine the radical possibilities of reality. Activists and designers Kenneth Bailey and Lori Lobenstine frame culture as a “policy of the irrational” that allows us to move beyond the rational and agreed upon to create deep and transformational change.23 Building on this, the writer adrienne maree brown reminds that, “all organizing is science fiction,” because organizers are engaged in the effort to create a world we haven’t yet experienced.24 A key radical potential of art lies in its capacity to untie itself from the pragmatic confines of political debate and act outside traditional forms of social power. Not only about re-envisioning, art can also reinforce and reflect worldviews. Parables, folk-tales, and other stories have long been principal means for expressing worldviews and meta-narratives.

Borrando la Frontera (Erasing the Border), Ana Teresa Fernández. Performance at Tijuana/San Diego Border, 2011. Photographed by the artist’s mother Maria Teresa Fernández, courtesy of artist and Gallery Wendi Norris

BORRANDO LA FRONTERA (ERASING THE BORDER)

Ana Teresa Fernández

Born in Tijuana and living and working in the United States, the artist traveled to the Mexican side of the border to complete a performance piece that imagined a gap in the border wall. Fernández painted the columns of the border wall to match the sky so that it looked like a section of the border had suddenly been removed. In this way, the piece moved beyond the slogans of “no borders” to allow us to see no fence, and momentarily, inhabit a world rooted in belonging that transcends national borders.

11. Making complex concepts more accessible

In many ways this is the most immediate potential of arts and culture, illustrated in the old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. While art can effectively illustrate existing ideas, and not only through visuals, it can also support a process of inquiry that makes complex systems and concepts more accessible and takes the work of research, policy development, organizing, beyond more narrow or singular conceptions of expertise. In social change organizations, communications staff are often tasked with taking up the bulk of the work to translate research-driven, academic, or insular language in forms and ways that will reach and move a wider variety of audiences. This work takes place through forms such as editing, design, multimedia, and storytelling. By collaborating more intentionally with artists and culturemakers and educators who understand critical pedagogy, this work can be especially critical to creating deep, authentic ways of communicating that avoids and resists techniques that are superficial or too closely derived from a corporate, profit-driven model of defining identity.

Video design and illustrations by: Abby VanMuijen (www.roguemarkstudios.com). Text written and narrated by Ananya Roy, 2013.

WHO IS DEPENDENT ON WELFARE?

Ananya Roy and Abby VanMuijen

In a video viewed nearly one million times, Professor Ananya Roy narrates an illustrated video that challenges assumptions about welfare, while illuminating the ways that government systems support wealth accumulation and wealth protection for the rich. The video uses playful illustrations to make otherwise abstract concepts concrete and meaningful. The novel form also pushed Roy to think of her writing and communication in a new way, as the backbone script for a visual story. By using an accessible infrastructure (YouTube) and an accessible form (an illustrated video) the video has greatly broadened the reach of her work on this issue, as much of academic research requires university affiliation or paid membership to access.

12. Expanding the reach

Art and cultural strategy allows our work to be in cultural spaces that people trust, refer to, and draw inspiration from. Art can happen in popular culture, it can be public, it can exist in and speak to different cultures, and it can appeal to different literacies, languages and learning modalities. At the Haas Institute, our work targets a variety of decision-makers as well as movements and impacted communities. Arts and culture can strengthen efforts to connect with under-reached people, hard-to-reach people, and those not politically or socially engaged. We’ve built on the work of those in popular culture to explore intersections and overlaps with themes and topics of the Institute. This includes leveraging the power of popular media narratives by hosting Tarrell Alvin McCraney (writer of Moonlight) as a keynote speaker at the Othering & Belonging Conference for example, and hosting free film screenings and dialogues around Black Panther and the 20-year anniversary of Gattaca. These efforts expand reach and create opportunities for narrative shift. This broadening of audience should be viewed through a targeted universalism approach–reaching which audience will bring benefit to everyone or be most widely accessible?

Reaching targeted populations requires new ways of communicating as well as the infrastructure for promoting the work. Rashad Robinson of Color of Change describes the need for an expanded infrastructure to advance progressive change efforts, “through social and personal spaces that aren’t explicitly political or focused on issues, but are nonetheless the experiences and venues through which people shape their most heart-held values.”25

Photo by Emmanuel Mbala, The crowd at a Melbourne screening of Black Panther, doing the Wakanda greeting. 2018.

INFLUENCING, SHAPING, AND USING POPULAR CULTURE

The most obvious form of expanding reach is through popular culture—TV, movies, music, sports, gaming and more. In recent years, popular culture has engaged and represented a wide range of issues that expands and complicates the cultural mainstream. Oscar winners Moonlight and Coco, and chart-toppers Lizzo (with her body-positive lyrics) and Lil Nas X (with both his country hit and coming out as gay) are only a sampling of new producers, themes, and cultural representations that are taking mainstage. These works, among others, tell stories that disrupt a single dominant narrative and cement a plurality of narratives in the mainstream. These representations and works also offer opportunities for new discussions and with new audiences, as evidenced by the number of discussion groups and articles that have engaged the contradictions and possibilities of Black Panther or Beyoncé’s Lemonade. Ongoing engagement around this work, and stronger relationships with cultural producers and cultural workers, such as the work of Harness an organization that supports action and engagement by celebrities with organizers, is essential for narrative saturation and the shape of those narratives and cultural forms in popular culture.

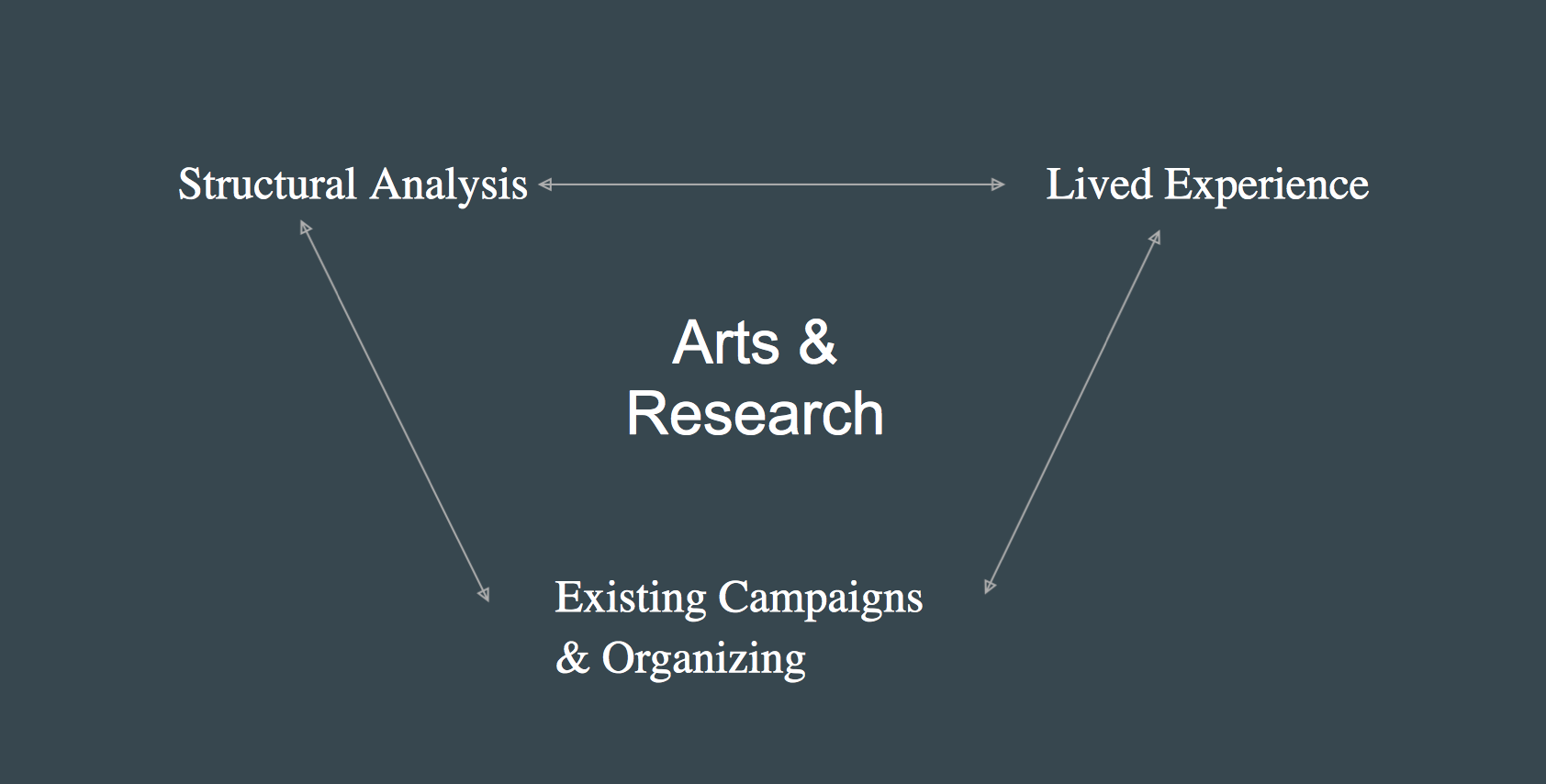

Four Essential Practices

There are numerous ways to activate cultural strategy. In the emergent work of a cultural strategy for belonging at the Haas Institute, we’ve identified four essential practices. These practices align process and outcome by balancing questions of leadership, knowledge and cultural production, and power, with questions of cultural strategy’s relationship to other change strategies.

1. Cultivate vibrant and diverse forms of cultural practice that support the growth of leadership and practice of those directly and deeply impacted by systems of oppression

This means building the power of people involved in the work by expanding notions of expertise and developing capacity and skills for long-term engagement and leadership. It also means highlighting and amplifying existing leaders who work primarily in the space of culture. This practice is deeply informed by critical participatory action research and Freirean pedagogy with a focus on art and culture as methods of research and analysis.26

Kerner@50 Student Art Collaborative, Nikko Duren, Kiana Parker, Dulce María López, and el lee Silver. Not pictured Ashley Holloway and Lulu Matute.

EXAMPLE

In 2018, the Haas Institute hosted a conference on the 50th anniversary of the Kerner Commission, a special presidential commission investigating the causes of racial uprisings across the nation in 1967. For this occaions, we commissioned original pieces from practicing professional artists in visual arts, poetry and performance whose work engaged the core themes; Damon Davis, Chinaka Hodge, Campo Santo, and Sadie Barnette. The conference also created the opportunity to facilitate a five-week intensive process with six undergraduate students to engage with the themes of the conference through the creation of collaborative artistic and cultural work. Through research and design processes they engaged the history in deep and personal ways. Their resulting creative works, which took the form of sculptural installation, mixed-media visuals, film, and a public presentation, expanded the conference learnings through additional forms of analysis and interpretation that brought in the power of symbols and broaders understandings of gender, immigration, and more.

2. Amplify the knowledge, insight and vision that comes through culture and cultural production and create containers and experiences where this knowledge, insight and vision can be expressed and understood on its own terms

Cultural forms and practices hold insights and knowledge in the form that they were created, and they can have highly specific audiences. When we are not the creators or even the intended audience, we can work to develop understanding in that original form, not as a translation. Illuminating practices, narratives, stories, frames, and symbols in their original form can provide important insight in developing systems and practices that are more reflective of the needs and experiences of a complex society and strategies for change. These multiple ways of knowing and expressing hold the transformative potential of a cultural strategy of belonging as an epistemological shift. At times, this means respecting and trusting the opacity of cultural practice and knowledge (trust is not, of course, uncritical acceptance). Anti-colonial philosopher Édouard Glissant defined this “as a right to not have to be understood on others’ terms, a right to be misunderstood if need be.”27 The act of uncritical translation or extraction of a functionalist knowledge can flatten, destroy, or misrepresent.

Nile Project, Aswan Gathering, 2013. Photo by Reto Albertalli

EXAMPLE

The Nile Project, co-founded by Mina Girgis, who is now a Senior Fellow at the Haas Institute, uses a process of cross-cultural, international musical collaboration to address water distribution and resources in theThe music invites cultural and environmental curiosity within the region, providing a metaphor for and practice of government and economic collaboration around the river. The project uses the unique process of musical collaboration developed by Girgis (master classes, musical “dating”, small group collaborations, arrangements and rehearsals) as the template for exchange and dialogue between scholars, students, and government workers across national boundaries. This process creates a radically different environment for discussion and a container for relating across difference–musically, politically, nationally and professionally.

3. Align with efforts for material, political, and social change

This means strengthening research, policy, and organizing projects through the knowledge, insights, and practices that arise within cultural strategy and creating opportunities for deep integration. It also means strengthening cultural strategy projects through the tools, knowledge and insights of other change strategies.

Staying Power Mural, Richmond, California. Co-led by Sasha Graham and Evan Bissell, 2017. Photo by Evan Bissell.

EXAMPLE

The Haas Institute’s Staying Power Fellowship convened a group of Richmond residents who were members of local community organizations to develop public art projects and narratives that addressed the housing crisis. In the eight-month process, they derived analysis from the intersection of personal experience and structural forces. The fellows designed research processes that shaped arts-based outcomes and cultivated their skills and leadership capacity through the process. The resulting artistic outcomes were developed by the fellows but also closely tied to and informed by the change efforts of the organizations and policy research around housing needs in Richmond carried out by the Haas Institute. Fellow Sasha Graham envisioned and co-led a process to develop a “know-your-rights” mural that celebrated the history of community organizing for the passage of two tenant protection laws and clarified key aspects of the laws. The production of the mural triggered an inquiry into the city’s implementation of one of the laws by local organizers and lawyers, which led to a year-long process of rewriting the policy and creating the structures for implementation, which had otherwise been dormant.

4. Make social and cultural change into a new “common sense.”

This means that cultural strategy efforts must also simultaneously engage strategic communications and narrative change work. Together, these efforts move through multiple spheres of life—the everyday, the political, the economic, and the cultural. It also means building the infrastructure for sharing and amplifying the work at scales and duration that begin to shift worldviews.

The “Making Belonging: Culturemaker Panel” at the 2019 Othering & Belonging Conference. The panel featured a conversation among four cultural leaders coming from different sectors, from left to right: author Jeff Chang, Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, actor Dawn-Lyen Gardner, and NFL player, philanthropist, and author Michael Bennett. Photo by Eric Arnold.

EXAMPLE

Since their inception, the Othering & Belonging Conferences have included an array of people working in cultural fields–playwrights, athletes, actors, dancers, and essayists to give compelling and evocative presentations on their work, alongside scholars, advocates, lawyers, funders and more. In 2019 the conference included the development of learning tools that employ arts-based teaching methods. This curation and approach allows for the trespassing of culture into a space where the audience is predominantly from the non-profit, government, academic, and philanthropic sectors. In this way, through major platforms, we present multiple, simultaneous ways of re-coding symbols and reframing narratives of belonging. This strategic communications and cultural strategy approach recognizes how an intentional integration of arts and culture elevates an interconnected, dual movement of social and cultural change and speaks to the power of stories and narratives that are crucial to influencing both. It seeks to connect personal, emotional, and professional understandings in ways that reveal continuity in this “common sense.”

Why a cultural strategy for belonging provides a unique opportunity for effecting change

A cultural strategy for belonging provides a unique opportunity for effecting change.

It has been said numerous times that culture is an essential site of change and power. This is due to the characteristics of culture that make it a unique location of social life. The Culture Group puts it this way; “Politics is where some of the people are some of the time. Culture is where most of the people are most of the time.”28

Culture is pervasive and everyday. It permeates multiple spheres of life, even the political, where styles of speech, dress, orientation to conflict, and theories of change create the conditions of political engagement. Culture shapes worldviews and values. Culture can erase and silence, and it can be a source of healing and strengthening.29 Naming cultural aspects and elements that have shaped my own life helps me better understand my own perspective and viewpoint. This includes those that have perpetuated othering—unearthing the way that conceptions of individualism and success are shaped by my socio-economic position growing up in a white, middle class family. And it includes those that have expanded belonging—the emergence of new values, symbols and stories that reshape my worldview through organizing, house music, and science-fiction (to name a few).

In the following section I explore why a cultural strategy for belonging is effective and holds potential by looking at three characteristics of culture that can help guide and locate the work

Still from the Get Out the Vote video We Are California, a collaboration between the Haas Institute and California Calls. Video by Dominique DeLeon, 2018.

Cultures of “othering” are dynamic and contestable

Culture is constantly made and remade through the expression of symbolic forms and the negotiation of their meaning between multiple parties. The maintenance of dominant forms of culture require upkeep–often in violent, erasing and manipulative ways. This contestation happens through multiple elements that make up culture and provide insight into locations of cultural strategy engagement.

Cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz outlines culture as: “A system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which [people] communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life.”30

Each of these elements are reciprocal and cyclical in their formation. Inherited conceptions are expressed through and embedded in symbolic forms; our interaction with and interpretation of symbolic forms communicate, perpetuate, and develop knowledge about and toward life; elements of this knowledge are disrupted or normalize and come to function as worldview. In further detail, these elements are:

Inherited conceptions. These are worldviews that come from the contexts of society, culture, community, religion, family and personal experience, and are shaped by socio-economic positionality.

Symbolic forms. Symbolic forms uphold and transfer the embedded information of inherited conceptions. These can take many forms, and also be material in their impact or structure. For example, money is a symbolic form of relationship that takes on different meanings based on positionality–do you see money as debt, power, obligation, love? These can take more direct forms as well. A mascot is a symbol that creates history and pride, but the meaning of it is shaped by the positionality and inherited conceptions of the interpreter–the name of the Washington professional football team, for example.

Means by which people communicate, perpetuate and develop their knowledge. At its base, this includes the many forms of language used daily–body, verbal, written or visual. These forms of language construct the stories and symbols that make sense of experience and become the basis of knowledge. Stories and symbols are made collective through infrastructures in multiple spheres of life–from personal to educational spaces to popular media to government policies and practices. The knowledges communicated, perpetuated, and developed through these means are frequently in conflict with each other–for example how a child might learn about a union if their family is in one, compared to how they might learn from news coverage of a politician who is anti-union.

Knowledge about and attitudes toward life. The development of one’s knowledge is a continual process. As this knowledge comes to shape one’s attitudes towards life, it influences and reshapes worldview and inherited conceptions.

Each of these elements are locations of cultural strategy. Voting in the United States provides an illustrative example. In addition to being a civic activity that has real consequences on the political system and socioeconomic structure, voting can be seen as a symbolic form of belonging or exclusion. Historically in the United States, this symbolic line has followed laws and practices that shape participation based on gender, race, class, status, relationship to the carceral system, and language. Research shows that a voter’s inactivity is rooted in how they view themselves in the world and their ability to have impact through voting or other forms of civic engagement.31 In other words, a person’s worldview shapes their interpretation of voting as an act in which they will participate or not. This is further communicated through a variety of means that either reinforce or disrupt that worldview—non-responsive politicians, voter ID laws, poll taxes, voting restrictions on formerly and currently incarcerated people, youth, and immigrants on the one hand, and projects like the Cultural Ambassadors program and Blueprint for Belonging on the other.

A cultural strategy for belonging works in alignment with the long struggle over expanding who controls voting, to also contest who controls the meaning of voting. This contestation of meaning happens in the production (what is the worldview being reinforced in the dominant narrative around voting?) and the interpretation (what is the worldview of the person interpreting the narrative around voting?).32

In decoding the meaning of symbolic forms, the interpreter’s worldview creates an understanding that is either consistent with that of the producers, inconsistent, or some hybrid variation of this. In religion, this has produced syncretic meanings, such as the embedding of indigenous stories, figures, and deities in the Catholic forms imposed by European missionaries in Central and South America. In his analysis of resistance and subordination in Southeast Asia, James. C. Scott also identified hidden transcripts, or meaning and communication that is hidden from people in different power groups. This allows people to perform an understanding in line with a dominant meaning through a public transcript, while also holding a different “hidden” interpretation as a key element of resistance.33 In relationship to voting, one way this might manifest is a worldview that is critical or distrustful of the political system, but also sees participation as a necessary act.

An interpretation that is inconsistent with the one the dominant producer intended, or the production of symbols and stories that hold different meaning, can contribute to reshaping worldviews. Nurturing these meanings creates opportunities for reworking the dominant narratives around voting. This can expand who sees themselves as a voter in order to build power around a strategic narrative of belonging and the policies that reflect economic and social belonging. In other words, although homeowners disproportionately vote at higher rates than renters, shifting inherited conceptions around voting can increase how many renters vote, and subsequently how tenant protection initiatives do at the polls or in the legislature.

Shifts in worldview are not enough alone, because these shifts will not be sticky unless also reflected in economic, political, and social changes. Contemporary organizing to lower the voting age, allow formerly and currently incarcerated people to vote, or keep polling places open and prevent people being scrubbed from voter rolls, are contemporaneous with ongoing efforts to shift who sees themselves as a voter. The double movement of systemic and cultural change are intertwined, reciprocal, and essential.

Cultures of belonging already exist in historical, collective and everyday forms

From below and from the margins, cultural expressions and forms, and the meanings and values they hold, can guide a cultural strategy for belonging. A cultural strategy for belonging builds upon alternative and liberatory forms of culture that people have developed before and within the dominant cultures of capitalism, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and other forms of oppression. These cultural practices and knowledge form through people loving and thriving, resisting and negotiating, acting spontaneously and keeping continuity, engaging ritual, tending memory, and experiencing grief and joy. As the Culture Group shared, culture is where most people are most of the time. But more importantly, these cultural forms are how people navigate oppression and what sustains people. Clyde Woods elaborates on the context of the emergence of the blues, and the power it held as a collective and everyday form:

“The blues emerge immediately after the overthrow of Reconstruction. During this period, unmediated African American voices were routinely silenced through the imposition of a new regime of censorship based on exile, assassination and massacre. The blues became an alternative form of communication, analysis, moral intervention, observation, celebration for a new generation that had witnessed slavery, freedom, and unfreedom in rapid succession between 1860 and 1875.”34

Arts manager and policymaker Roberto Bedoya offers another example in rasquachismo, a practice of Chicano and Mexican art movements that is combinatory, quick, reuses materials, and is often crude and direct. For Bedoya, the rasquachismo aesthetic of his Bay Area childhood barrio signaled a politics of belonging that disrupted a white spatial imaginary. He writes that the unique cultural spatial imaginary of Rasquache is in the “culture of lowriders who embrace the street in a tempo parade of coolness; it’s the roaming dog that marks its territory; it’s the defiance signified by a bright, bright, bright house; it’s the fountain of the peeing boy in the front yard; it’s the DIY car mechanic, leather upholsterer or wedding-dress maker working out of his or her garage with the door open to the street; it’s the porch where the elders watch; and it’s the respected neighborhood watch program.”35

The development of strategy in line with cultural forms like these can create social change processes that are reflective of people’s lives and experiences and widely accessible because of their everyday, collective, and historical character. They are also effective, having already worked “in situations of scarce resources and intersecting systems of oppression,” and so they, “tend to be the most holistic and sustainable.”36 The turn to strategy can take shape in many ways; the trespassing of poetry into a city council presentation for the Staying Power Fellowship, a healing space with multiple alternative modalities at the Othering & Belonging Conference, and the placement of a theater talk-back in an Oakland barbershop. Each build on, adjust or amplify existing forms of cultures of belonging.

Beginning to inventory and name the infinite traces and influences that we build on in our work is essential for valuing this history, creating continuity, and not losing that which has come before. It also helps to push away from the idea of individual cultural producers or geniuses acting on their own. Instead, we can recognize the specific lineages and histories (and often invisible labor) that goes into the collective and everyday forms of culture that provide essential wisdom for creating belonging.

Leading up to the 2018 Barbershop Chronicles performance at UC Berkeley, a community forum was held at Benny Adem Grooming Parlor, presented by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, Benny Adem Grooming Parlor, Africanity Love, Priority Africa Network, and the Black Alliance for Just Immigration. Photo by Tim Shonnard.

Cultural forms and expressions can advance belonging despite asymmetries of power

Cultural moments, knowledge, expressions, practices and forms can catalyze change when other avenues of change are stagnated, closed off, unimaginable or heavily policed. This happens even in the case of social, economic, and political imbalances and repression, and ultimately can contribute to the ending of those imbalances. From punk to muralismo, slang to voguing, cultural forms create their own spaces of belonging and expressions of belongingness that seep across boundaries that are seeking to maintain exclusion and dehumanization. At times these “crossings” are co-opted and sanitized for dominant cultural audiences in pursuit of profits and the erasure of the people and contexts of their origination. But at other times (and also when co-opted) these cultural forms and expressions can build social, economic, and political power.

In part, this ability to move across seemingly impenetrable borders is possible because culturemaking cannot always be shaped or guarded by gatekeepers that reinforce the status quo. The irrepressibility of cultural expression is too organic and spontaneous, and frequently built on DIY or minimal infrastructure.37

In academia, media, law, politics, economics, and policy development there has historically been an intensive safeguarding and policing of who can produce knowledge, what knowledge is valued, how it is valued and what is made actionable. These sectors, which largely set and enforce social, political and economic systems, have tightly controlled infrastructure for the reproduction of experts, leaders, and workers and the broadcast of the work.

These gatekeepers undoubtedly exist in cultural spaces as well. At times this gatekeeping is a protective response to the erasure precipitated by cultural appropriation. But there are also those who attempt to shape the “proper” evolution of a musical genre, the visual style of a movement, or the acceptable forms of sexuality in film. Infrastructure is also a site of cultural gatekeeping: the owners of popular and independent media, publishers, grant-makers, radio hosts and their playlists, and curators and museum directors, among others.

The Hōkūle‘a double-hulled voyaging canoe, which since its first launch in 1975, has sailed over 140,000 nautical miles. Courtesy Polynesian Voyaging Society. Photo by ʻŌiwi TV. 2015.

Despite this, new forms and expressions of culture inevitably rise, often forged in contexts of extreme inequality and little-to-no infrastructure by people continually engaged in adapting to the challenges, expansions and conditions of everyday life. While difficult to track impact in linear or direct ways, and although not necessarily intended as cultural strategy, these cultural forms and expressions can build social, political, and economic power, while also shifting narratives and worldviews. Consider the global impacts of hip hop in comparison to its early infrastructure (a blank city wall as a canvas, a piece of cardboard as a dancefloor, reworked fragments of songs and daisy-chained speakers) and originators (poor Black, Puerto Rican, and Dominican kids in disinvested neighborhoods of New York). Or, after 600 years of dormancy, consider the way the first wayfinding (celestial navigation) voyage by Nainoa Thompson and crew, on a hand-built, double-hulled sailing canoe between Tahiti and Hawai’i, cultivated the renewal of Hawaiian culture, history and identity. Was it imaginable that the 1969 occupation of a defunct federal prison by Indians of All Tribes would catalyze such a revitalization of Native American political and cultural identity, and have such a long trail of impact? Was the mainstream uptake and breaking of political taboos around class and economic inequality assumed when the 99 percent began tent occupations around the country?

With these, and many other examples in mind, a cultural strategy for belonging recognizes that cultural forms and expressions can have sustained and material impact despite and within asymmetries of power.

Next steps for a cultural strategy for belonging