In Montgomery County, Maryland, a racial and climate justice effort of BIPOC, multi-faith, community leaders, community-based organizations, and government allies used a series of structured discussions to decide on their collective approach to achieving transformative change in the county. Focus groups and structured discussions use dialogue to uncover a group of individuals’ opinions or experiences about a particular inquiry. A facilitator (or multiple facilitators) guides the discussion that collectively generates knowledge across participants using questions that are rooted in the PAR inquiry and purpose and are carried out in a process that affirms participants’ lived experiences. Structurally, focus groups have a small number of people (typically five to eight) and aim to set an accessible, welcoming, culturally relevant, and nonthreatening environment.

In Montgomery County, the passion for change was overflowing within the community, yet the base building and place-based organizing infrastructure in the county was limited. Knowing that investing in a sustainable community infrastructure is essential for community self-determination, a handful of group members, with the support of a PAR facilitator, organized a series of structured discussions to identify community assets and needs. Belonging and power building rose to the top in order for the community to build capacity and social infrastructure to make racial and climate justice real.

From there, the group underwent a series of interactive, life-affirming focus groups and structured discussions to build shared definitions, align on community priorities, create a transformative vision, and explore how to go about realizing that vision. Using an iterative focus group and structured discussion method gave the group flexibility to explore rather than operating from predetermined parameters that stakeholders may be bringing into the collaborative. It also gave the process enough structure to support the group in building governance capacity and community member leadership.

Meetings and activities also included collaboratively analyzing meeting data and making decisions using consensus-based practices. With a strong foundation established, the group is focused on cocreating a racial and climate-justice popular education initiative in frontline communities that cultivates capacity. The multi-stakeholder process also successfully secured a $300,000 community justice fund from the county government that renews each year to continue the work.

What Type of Knowledge Focus Groups and Structured Discussions Generate

By holding skillfully facilitated group discussions, you can not only learn about what individuals think or feel about something, but also you can generate more creative ideas on an issue than in an individual interview. This is because during the discussion, the group can learn from one another in real time. Also, learning how folks respond to and are influenced by each other provides insight on how language and framing of justice and equity issues plays out among people, offering a window into how it might play out in the broader community. More meaning is made by analyzing the focus group data, typically across three or more focus groups or structured discussions.

Some specific ways to use focus groups include:

- guiding a community visioning processes

- building a menu of community priorities

- exploring nuances around identified community priorities

- brainstorming potential solutions to an issue

- gaining insights to inform decision-making

How Focus Groups Can Build Relationships and People Power

Focus groups are an opportunity to cultivate connections and peer learning and to spark shared purpose or calls to action. Focus groups allow organizers to stack functions to collect data to identify the best actions for positive change. They can also reduce feelings of isolation and the false and harmful narrative that people are alone or that the marginalization they experience is something they must simply endure or address on their own. It can activate a sense of “power within” and “power with” in bringing people together to talk about a shared issue in their community.

Focus groups can also bring people together who already know each other, depending on the research purpose and design. This can build power by deepening relationships, and the structured, focused discussion holds intentional time and space for people to hear each other’s perspectives when they may not have made intentional time for this type of discussion otherwise. In a context where they are experiencing an activity together, it builds a sense of community, which is not necessarily the case for interviews.

Focus groups and structured discussions can lead to recruiting members and cultivating a bigger movement for the cause. As people connect over shared values, priorities, lived experiences, and more, it can inspire people to get involved, ranging from staying aware of the effort to joining into the PAR process more intentionally.

Don’t forget to include a sign-up sheet for people who are interested in learning more or getting involved after the focus group!

Time, Capacity and Resources, and Tools Needed

On the one hand, focus groups are time consuming when it comes to planning, prep, and logistics. On the other hand, they can save time in comparison to interviews once they are planned out because you are able to gain a lot of perspectives at once rather than one at a time. They are complex discussions and require a skilled facilitator or moderator and an environment that is welcoming, life-affirming, and supports generative dialogue and at least one notetaker. Materials and tools needed are the focus group guiding questions, a recording and transcription tool such as Otter.ai (if consent is given to record), notetaking materials, any interactive materials for the discussion, and food. For analysis, qualitative analysis computer software programs such as Taguette or Dedoose can be helpful, but low-tech processes also work!

Focus Group Questioning Design

Depending on the context and how you plan to use the data from the focus groups, the questioning strategy could be a topic guide or a questioning route. A topic guide is an outline of the topics to be discussed in the focus group with phrases or words that cue the facilitator throughout the session. A questioning route is more like a script that is meant to be followed consistently across focus groups. The questions are written in a particular sequence in conversational sentences. A topic guide can be advantageous when the focus is to uncover nuances and ideas. It allows the facilitator to hit all of the key topic areas, but in a way that meets participants where they are in their dialogue in real time. A questioning route can be helpful when you need rigorous consistency across focus groups, such as understanding what language resonates for a campaign or if the crux of your data is from focus groups and you don’t want your opposition to poke holes in your research and solutions.

In developing the questions, keep the PAR project purpose top of mind to guide you as it is easy to develop too many questions and get distracted by the complexity of the issue you are examining. Typically, questioning flow includes opening, introductory, transition, key, and closing questions. Each category has a specific purpose to facilitate the flow of the discussion. Sticking to ten to twelve questions total for a two-hour discussion is a solid rule of thumb. They should be open-ended, concise, clear, and engaging.

Once you develop your questioning design, it’s a good idea to try at least one dry-run focus group with family or friends. Focus groups take a lot of time to orchestrate, and you don’t want to do all of that labor just to find out that your questions are confusing or don’t actually get at what you are trying to learn. Once you start your focus groups, changing your questions limits your ability to compare and contrast data across focus groups.

Connecting the heart and mind in your questions is a good idea since we may rationalize what we think about something, but we often learn our internalized beliefs and values through connecting to our feelings. Creative questions that involve interactive activities, such as drawing pictures and visualizing, can connect to the heart.

Conducting Focus Groups

Participatory focus groups and structured discussions should aim to set up a life-affirming environment. The questions are also coming from people who have similar lived experiences or identities, so they often are relevant and easy for focus group participants to understand and respond to. Make sure to practice the question flow and plan ahead for how much time to spend on each question and the pacing of the questions. Having a skilled facilitator who is rooted in the community is ideal as this can deepen a sense of trust and willingness to be vulnerable and honest for participants. Active listening is essential, and laying out ground rules for participants to also actively listen is important too. For ease of data organization after the focus groups, make sure to have a system for how you plan to take notes across all notetakers. Lastly, be flexible and adaptable. Just like organizing, focus groups can be unpredictable.

Processing the Data

Processing the data means putting the focus group notes and transcripts into an organized place (Google Drive works well) to ready them for group analysis. It also includes cleaning up the notes and transcripts so that they can be easily understood and accurately represent what was said.

Analyzing the Data

Collaboratively analyzing qualitative data is a laborious and rewarding process. It is an incredible way to deepen a shared understanding of the issues at hand and what your community is saying about them. You can start by having the PAR team review transcripts and notes. Sometimes this isn't possible, or accessible for all participants, so you might need to build in shared work time to get comfortable with the transcripts together.

Having a few people take on a deeper analysis of looking at themes and patterns and identifying quotes that exemplify those patterns can be an effective approach. But it is important that this doesn’t revert to only the “most experienced” or “most academic” people in the room.

Then, bring together the larger team again to review the themes and patterns the small team identified. This supports a more inclusive, rigorous process and can minimize any unintended biases. Additionally, you might decide to share a preliminary summary of themes with the broader group (including focus group participants) so they can offer questions to elucidate further analysis and learnings.

Pitfalls, Challenges, and Myths

Underestimating: With focus groups, the cost, time, and level of coordination required are key areas that get underestimated. Clear planning, adopting a stance of flexibility and iteration, and most importantly, being really grounded and aligned on the purpose of the research are great ways to mitigate the tendency to underestimate focus groups and structured discussions. Taking time to set clear team roles and to build trust can alleviate confusion that often emerges in the context of underestimating.

Coordination and maintaining consistency: Focus groups require a lot of coordination in setting up, in building aligned approaches (if multiple facilitators are holding the focus groups), and in the analysis stage. Coordination is important because it ensures consistency across the PAR team when doing your research. Alignment and purpose clarity are key. Organizers are typically well versed in coordination, so bringing that skill to ensure your focus groups maintain consistency is a great way to leverage existing capacities.

Additionally, during a focus group, be prepared for things to not go as planned. This includes unexpected silence or limited sharing, conflict, environmental disruptions (e.g., weather, traffic, community emergency), and more. Again, bringing your organizing skills can enable PAR processes to be more successful and adaptive than dominant academic approaches to research.

Weaving in Cultural Strategy

From a cultural strategy standpoint, storytellers know that the setting is a vital and revealing character in any story. Settings can be intimidating, familiar, playful, severe, scary, warm, nostalgic, and much more. Focus groups can learn from this by paying attention to the setting they are creating—something artists are adept at doing as a way to get into deeper knowledge generation and sharing.

For example, in her play Mirrors in Every Corner, playwright Chinaka Hodge set the most dynamic and honest conversations about race dynamics within a Black family in Oakland at the card table as they played Spades. The community-engaged artist Rick Lowe has been known for spending a good part of his days at a dominoes table with neighborhood residents.

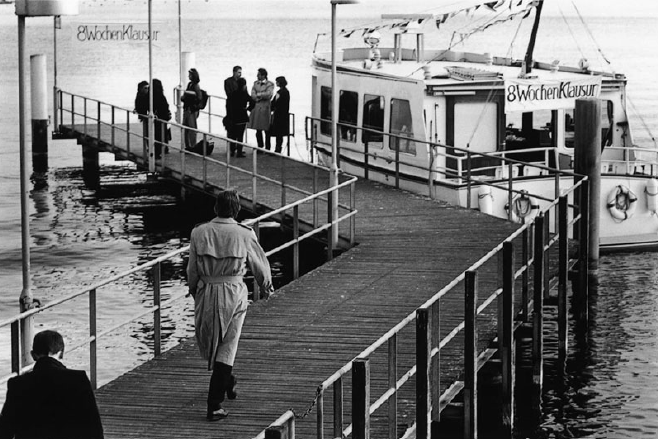

Other collectives have used intergenerational meal prep as a way to discuss elders’ stories about war and migration. In one particularly elaborate example, the artist collective Wochenklausur held structured discussions between elected officials, sex workers, and advocates in the metaphorically neutral zone of a boat on a lake (they were successful in securing permanent housing for the sex workers).

Related Resources

- “The Basics: Focus Groups, Listening Sessions and Interviews” by Kris Johnson and Hani Mohamed of Communities of Opportunity and Communities Count

- “Community Toolbox: Conducting Focus Groups” by the Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas

- “Designing and Conducting Focus Group Interviews,” by Richard A. Krueger, is a concise resource with specific steps and tips on conducting group interviews.

- “Four Participatory Research Methods Every Organizer Needs to Know” by the Data Center