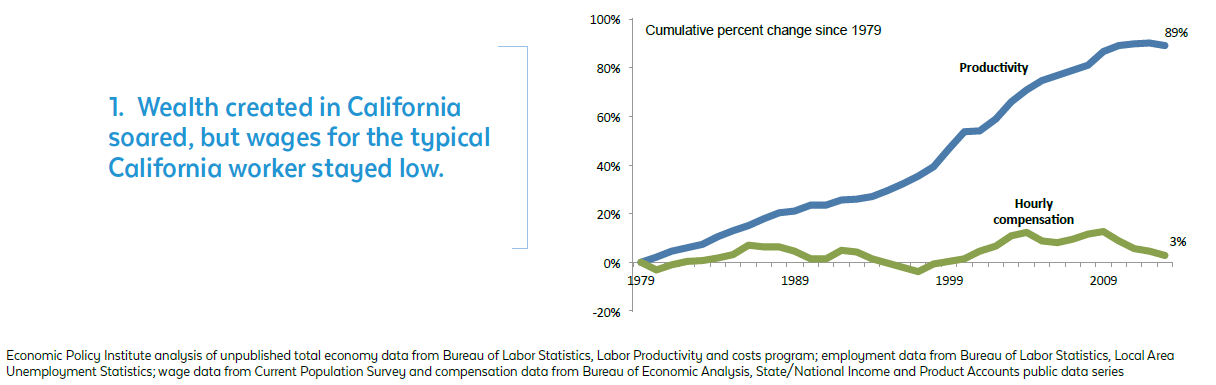

For many Californians, having a good life here is getting harder and many feel it will be even harder for the next generation.1 There are glimpses of the so-called California dream but also moments of a California nightmare. California was once among the states with the greatest economic equality, the best schools, and the most affordable homes, but it now has such severe inequality that it is one of the five most unequal states. The middle fifth of California workers make as much in a year as the top 1 percent makes in a week.2 California now has the highest poverty rate of any state in the US, with persistent poverty affecting more than one out of five Californians.3 People of color have been hit hardest; poverty in California afflicts 29 percent of Cambodian Californians, 35 percent of Black families and 40 percent of Latinos. Black Californians are five times more likely to be incarcerated than white residents, and the state spends more on incarceration than on public universities.4

Californians are incredibly hard working and innovative, which is proven in the state’s unparalleled economic productivity and wealth. The economic challenges facing California are not for lack of money; the state has more billionaires than any state and any country besides China and the U.S.. Some feel California is starting to turn the corner toward a more fair and inclusive society, yet economic opportunity, the cost of living, even a livable environment and owning a home are still out of reach for far too many. This raises the question:

what are the forces underlying the challenges facing California, and how do we ensure that the changes underway now are transforming these forces?

This short paper draws from insights by researchers and organizers involved in the Blueprint for Belonging project to offer an analysis of the structural forces shaping California.

CALIFORNIA'S ROOTS

The story of California has its roots in a centuries-old saga of cycles of oppression and opportunity, of conquest and compromise, of promise and betrayal, of enrichment and inequality, of struggling and overcoming. The early history of the Golden State is the epitome of the American myth of rugged individualism, Manifest Destiny and white supremacy. It was a territory colonized by white settlers on land expropriated in a war with Mexico (1846 – 1848), which left former Mexican citizens cut off from their native land and government, and forced indigenous people, who had never accepted Mexican rule, into a new conflict with the U.S. government.

The California Gold Rush Era (1849 – 1855) attracted a flood of fortune seekers to the territory/state. Some 300,000 gold-seekers, merchants and others, including escaped slaves and freed African Americans migrated to California during this time. They came primarily from other parts of the U.S. but tens of thousands of immigrants from China, Mexico, United Kingdom, Australia, France, Mexico, and many other countries also flocked to California.

As gold extraction became mechanized and industrialized and as trade and commerce expanded, California became the center of a new myth, “The American Dream.”

California was transformed from a sparsely populated, unknown territory to a center of the global imagination and the destination of hundreds of thousands of people.

Waves of migration followed, from the Filipinos in the early 1900s to the Great Migration of African Americans from the South, to the migration of 'Okies' from the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma.

EFFECTIVE GOVERNMENT… FOR SOME

In the 1940s and 50s, government investment in education, industries, and infrastructure made California a place of greater opportunity, inspiring people of all ages to move here from around the US and around the world. Many came for the good, accessible jobs like those in the factories with government contracts to produce ships and planes for WWII. Some also saw less racial exclusion compared with the harsh Jim Crow racism in the South. Corporations invested in workers with living wages, pensions, and even no interest loans for a first mortgage. The state of California invested massively in public goods like freeways and universities. Through the GI Bill, the federal government provided free college and free down payments on homes to over 12 million US citizens. California created fifteen new UC and CSU campuses from 1947-1965, more than doubling the number of campuses. Economic inequality was among the lowest in the country.

The economy and the government were well-resourced - they were creating greater opportunity - but they weren't inclusive.

Racial discrimination was pervasive and created barriers for people of color to fully access education, housing, and jobs. Segregation was maintained in schools, neighborhoods, unions, and industries. Private discrimination like property deeds that prohibited selling a home to a person of color were combined with discriminatory public policy, like home loan subsidies that were only available in neighborhoods with these racist deed restrictions. Segregation was violently enforced by mobs attacking Black families who attempted to move into white neighborhoods.5 More than 93,000 Californians of Japanese descent were rounded up and forced into internment camps, losing their homes and businesses.6 Most unions were white-only, and most schools were racially segregated. New freeways were built in ways that cut off traditionally African American neighborhoods, while creating a pathway to opportunity for the predominantly white people who had moved to the suburbs.

In other words, the public investments in education, infrastructure, and industry were creating opportunity that had selective access.

Government ignored and actively supported racial exclusion, and got backing from the voters, who even at the end of the 1970s were the majority at 83% white.7

COMMUNITY POWER… AND WHITELASH

African American, Latino, and Asian American communities organized movements in the 1960s that directly confronted the racial exclusion they experienced. From the Mexican and Filipino farm workers in the California fields, to young Chican@s in LA public schools, to the Black Power and Civil Rights movements in Oakland and LA, communities of color built power to demand new institutions and racial and economic justice. These movements led the way to more inclusive opportunity – breakfast programs for children in need, community policing, bans on employment and housing discrimination, and other policies. They also generated new political identities that have shaped movements and society ever since.

But the rising calls for justice, an economic recession, and access gained by communities of color were met with a new partnership between corporate elites and reactionary whites that stoked and exploited racial anxiety and resentment.

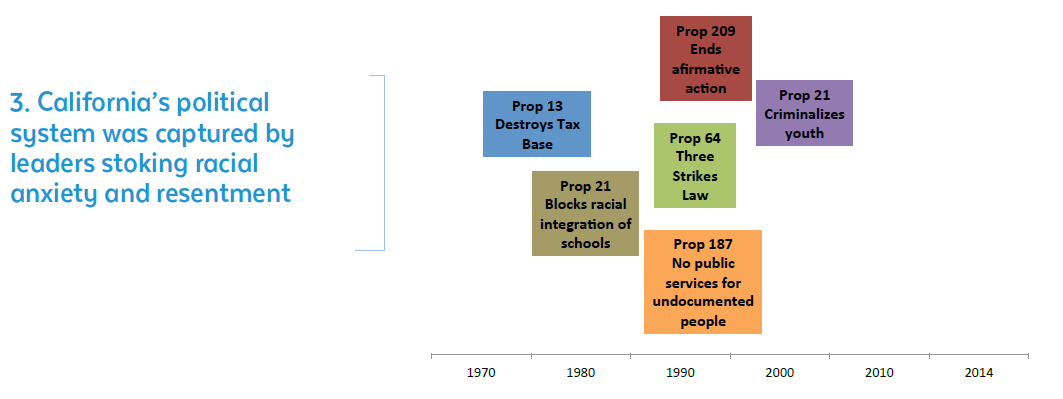

When civil rights groups convinced the state legislature to pass a 1963 law to ban racial discrimination in housing, the California Real Estate Association put proposition 14 on the ballot to add the ‘right to discriminate’ to the state constitution. Proposition 14, which would remove the ban on housing discrimination, was promoted by stoking fear of government-overreach and celebrating individual property rights, and was supported by nine out of ten white voters and passed with 65% of the votes.8 While proposition 14 was struck down by the Supreme Court two years later, the alliance of reactionary white voters and corporate elites and their narrative of property rights and limited government, had been solidified.

NEW NARRATIVE ESTABLISHED

Proposition 13 tested and then solidified the alliance of reactionary whites and corporate elites around their narrative of limited government, individual property rights, and racial resentment. Rapidly increasing property values in the 1970s also meant increased property taxes for many homeowners, creating a strong interest in limiting property taxes. Proposition 13 in 1978 drastically limited property taxes for homeowners and corporations, causing such a massive loss of public revenue that most corporate interests, including the chamber of commerce and statewide industries and banks, opposed proposition 13 before it passed. The campaign for proposition 13 used the narrative that government was overreaching, and was unfairly serving people of color. A common mailer asked voters, “Are you willing to pay higher property taxes to finance the forced busing of over 100,000 Los Angeles school children?”9 After they hadn’t supported it before the vote, corporate elites, Jerry Brown and leaders across the spectrum changed sides and backed the similar Gann Limit Proposition 4 the following year. The narrative had become dominant, crossing party lines and backed by powerful, wealthy interests.

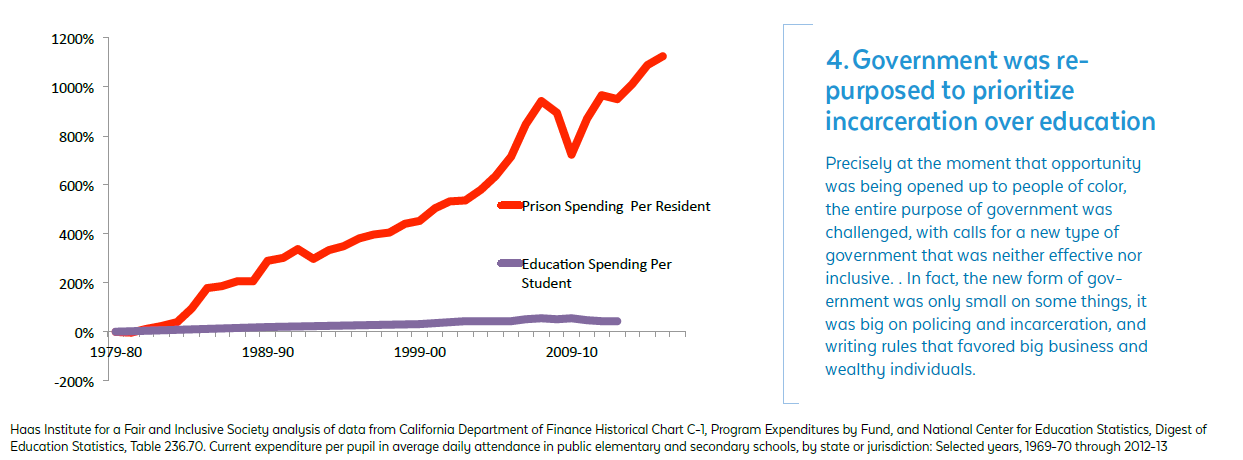

Precisely at the moment that people of color were gaining power to make government more inclusive and responsive, the entire purpose of government was challenged with calls for a type of government that was neither effective nor inclusive.

The idea of 'small government' was often justified with a narrative that government was 'taking from the makers and giving to undeserving takers' – taking from whites and giving to people of color. What it meant in practice was the re-purposing of government away from public interest towards big business interests. The narrative was applied in California by Democrats and Republicans alike. Jerry Brown, in his first stint as governor, and other democrats promoted an 'era of limits' on government.10 For forty years now, Democrats have had a majority in the California State Senate and State Assembly, and five out of seven executive offices, except for three years from 1995 to 1998. It was during this forty year period that the politics of ineffective government, individual rights, and corporate economics became dominant.

ECONOMIC RESTRUCTURING

Tied closely to the repurposing of government was an economic restructuring that resulted in disappearance of middle class jobs and a massive growth of low wage jobs. Corporate America and federal and state governments colluded to facilitate deindustrialization and the relocation of factories to Asia and Latin America, resulting in wage stagnation and high unemployment in the U.S. More than 30 million jobs vanished in the 1970s in the U.S.

One response to this restructuring in California was to place hopes on the emerging tech sector. In 1982, Governor Brown and others proposed that the tech sector would replace jobs lost to deindustrialization.11 The tech sector was expanding with new computer technologies, facilitated by tax payer funded research conducted at some of the public universities. Publicly funded research had developed the internet, Geographic Information Systems, touch screens, and other technologies which made possible vast arrays of new products and services.12 These technologies were turned into highly profitable products and services like superconductors, cell phones, and internet services. In the end though, the tech sector generated far fewer jobs than previous industries.12 A company like Google earns $16.3 billion in annual profit, yet has only 57,100 workers. For comparison, General Motors earns just over half as much, $9.7 billion annually, and employs four times as many people as Google (216,000 workers).

The majority of the new jobs turned out to be in industries with low wage jobs: food services, retail sales, security and others.

Walmart became the largest employer in the country.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE AND DOG WHISTLES

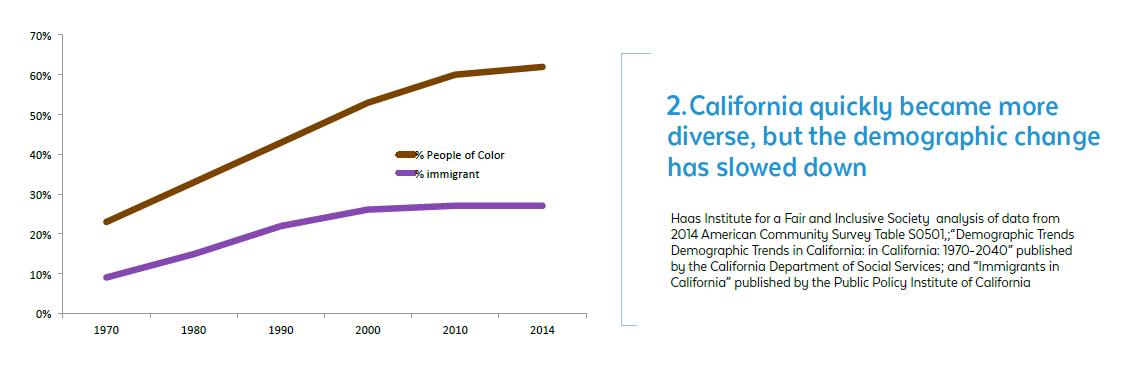

Increasing numbers of Latin@s, Asian Americans, and immigrants of color in the 1980s and 1990s created rapid demographic change in the state. Extreme poverty and exclusion in Mexico and other countries, caused in part by U.S. trade, investment and foreign policy, led large numbers of people to immigrate to the US, primarily to California. The population in California went from being 9% to 22% immigrants between 1970 and 1990. During the same period, the state population went from 23% to 43% people of color.13 But this demographic change in the population did not happen as quickly in the voting population. Even by 2009, whites were 43% of the overall population, but were 65% of the registered voters.7

The loss of economic opportunity and demographic change experienced by whites in California created a fertile landscape for political leaders in California to increase control of government using dog whistle politics. These leaders and the media focused voters' attention on a demonized scapegoat - the 'illegal immigrant', the 'super predator gang member', the 'welfare queen'.

Race was implied but not mentioned explicitly, allowing people to claim they were not being racist.

The use of these racially coded messages that refrain from mentioning race explicitly but trigger racial resentment and inspire voters to act on it became a central strategy for maintaining the small government narrative and gaining political power. Pete Wilson was perhaps the most famous example, with his campaign in 1994 for proposition 187, which sought to ban undocumented immigrants from schools, hospitals, and public assistance. In a TV ad for proposition 187, a narrator delivers the message, “They keep coming… the federal government won’t stop them, yet requires us to pay billions to take care of them”.14 The dog whistle campaigns were coupled with initiatives like 187, 'three strikes', and others that expanded policing and incarceration to levels never seen before. Even when implementation of an initiative was blocked by the courts, as happened with proposition 187, the campaign to pass it had already profoundly shaped identities and politics by cultivating anti-immigrant sentiments.

REPURPOSED GOVERNMENT

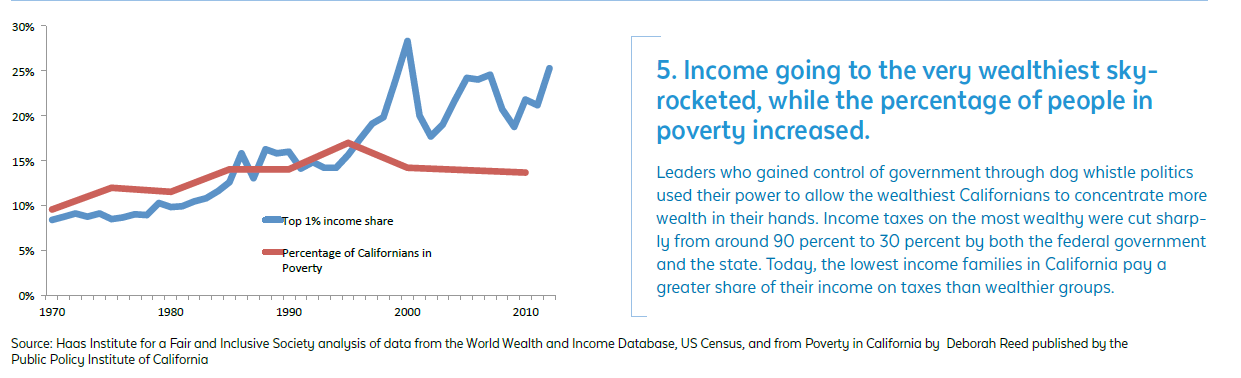

The leaders who gained control of government through dog whistle politics used their power to repurpose government.

They set new rules for the economy that allowed the wealthiest Californians to concentrate more wealth in their hands.

Income taxes on the most wealthy were cut sharply from around 90 percent to 30 percent by both the federal government and the state. Real property taxes in California were capped by Proposition 13 in 1978, a dramatically regressive step because ownership of real estate is concentrated among the wealthy and the businesses they own.15 Of the seven billion dollars in immediate tax cuts enacted by Proposition 13, fully five billion went to corporate pockets.16 Today, the lowest income families in California pay a greater share of their income on taxes than wealthier groups.17 During this same time, energy corporations saw a chance to rewrite the rules of California’s energy system, and spent $69 million in political spending and lobbying to do so.18 They won, and energy deregulation was signed into law by Governor Wilson in 1996. Landlords also won a new set of rules with the passage of the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, a 1995 law that weakened protections for renters across the state.

The era of a government that was well-resourced enough to expand opportunity –that created an infrastructure for belonging-- was over. Public investments in education, industry, housing, and other engines of opportunity were slashed, and only policing and incarceration were prioritized. Inadequate public funding for schools meant a two-tiered system where only the public schools in wealthier neighborhoods would be good because there were families that could raise substantial amounts of private money to subsidize them.19 Mediocre education in low income communities limited access to good new jobs and fed the school to prison pipeline.

The dog whistle politics that scapegoated people and immigrants of color went hand in hand with a repurposing of California’s government to prioritize incarceration over education. During the 1990s, the California legislature passed more than 400 bills that made sentencing more severe and punitive.20 Prison spending per resident increased more than 1,000% between 1980 and 2014, while education spending per student only increased 43%.21 California built 21 prisons in 20 years, and the number of people in prison grew by over 800% from 1978 to 2008.22 Mass incarceration tore families apart socially and economically, and created stigma that prevented people from getting back into the job market upon community reentry. Immigration rules and workplace exceptions almost guaranteed extreme low wage jobs in agriculture and food service.

In fact, the new form of government was only small on some things, it was big on policing and incarceration, and writing rules that favored big business and wealthy individuals.

Rules were also re-written to make state and local government less responsive. Prop 13 created a requirement that a two-thirds majority was needed in the legislature to pass any new tax or public revenue measure. This meant that a group of state officials that added up to one third plus one could block legislation. Those advocating ineffective government did not need a majority, they needed just one third plus one. Similar rules followed making government less and less responsive to communities and workers.

CRISIS OF INEFFECTIVE GOVERNMENT

While California in the 1990s was the climax of the state being ruled by corporate elites and reactionary whites, the next decade was when the new laws generated crisis after crisis. The result of energy deregulation was a year with 38 rolling blackouts across the state and an increase in the average energy price for residents increase of more than 400%.23 The number of people in prison was more than 7 times as large as it was in 1980, to the point where more Black men were in California’s prisons than in its universities. Even though the state had built 20 new prisons in 20 years, it still didn’t have enough space and the Supreme Court finally stepped in and ruled that the overcrowding was cruel and unusual punishment.

The effect of the drastic cuts to taxes was to bankrupt government and make it incapable of creating broad prosperity. In 2008-10, California was so short on funding that it had to issue IOUs to its employees, school districts, and local governments. The state then cut about $20 billion in public spending, mostly cuts to health and human services for the extremely poor, disabled, and others in need. By this time, California’s once famous public education system was bankrupt and among the worst in the nation.

WEALTH STRIPPING

Meanwhile, the restructuring of the economy and the new rules empowering corporations allowed for new forms of wealth stripping from low income neighborhoods and communities of color.

Beginning in the 1970s, new rules on banks, mortgage companies, hedge funds and other financial institutions freed them to engage in high-stakes, speculative lending and trading. This led to a spree of junk bonds, exotic derivatives and other instruments that were part of successful get-rich-quick operations. The subprime mortgage crisis and Great Recession of 2007-2009 were brought on by unscrupulous mortgage lenders who steered unsuspecting customers into loans laden with unfair terms, usurious interest rates, and unaffordable monthly payments. These mortgages were then “bundled” into marketable securities that were sold as highly rated investments on the open market. When the underlying mortgages went into default, the shock waves triggered the collapse of the financial markets, immense losses by many homeowners and a contraction in the economy that cost many people their jobs. In the end, $7 trillion in wealth had been stripped from homeowners.24

California financial institutions played a major role in this unfolding process: California companies were the number one subprime lenders.25

The chain reaction was felt disproportionately by black and Latino families: wealth fell by 66% among Latino households, 54% for Asian Americans and 53% among Black households, compared with just 16% among white households.26

To add insult to injury, these speculative ventures, unlike investments in manufacturing, generated very few jobs and very little wealth or income for working people, only immense wealth for the 1%. The communities hardest hit also go to schools hardest hit by inadequate funding and privatization by charters operated by some of the same capitalists that caused the subprime mortgage crisis. The impacts are still being felt in communities in California and across the country.

Wealth stripping also occurred in more indirect ways, such as the money made off of mass incarceration and the privatization of schools. Many of California’s prisons were financed by private investors who in the end made 1.5 to 3 times their investment, including Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley investing more than $2 billion. Charter schools have also been similarly financed by wall street banks. Prisons were used as a substitute for economic development, providing jobs in depressed rural areas of California. Bail bonds companies profited off people awaiting trial for an immigration or criminal charge.

Entire industries had emerged, extracting untold wealth from communities targeted by mass incarceration and criminalization of immigrants and people of color.

COMMUNITY POWER RESURGENCE

The attacks on communities of color in the 1990s did not go without a response. They in fact brought on a resurgence in grassroots organizing in communities of color and the formation of local and statewide organizing, policy advocacy and get out the vote networks that have won significant policy victories. Although increases in the percentage people of color and immigrants had happened in the 1980s and 90s, it wasn’t until organizations and movements were built to turn this demographic potential into political power.

This strengthened infrastructure for low income communities of color and allies produced numerous victories: increasing the minimum wage, allowing immigrants rights like a driver’s license, and eliminating some of the worst criminal justice laws that drove incarceration. The California legislature passed ground-breaking climate change policy AB32, followed by SB 535, which requires 25% of funds go to communities that have had the most severe environmental conditions. Voters in 2012 passed proposition 30, increasing the tax on the wealthiest one percent and generating public funds to increase education spending per student and reduce class sizes.

California has begun turning the corner in what could be a new era.

This may be the beginning of re-purposing state government so it is inclusive and effective, and creating an economy that works for all.

REALIGNMENT OF CORPORATE POWER?

There may be a new alignment of corporate power underway now. In the late 1970s, corporate elites and reactionary whites formed a structural force focused on the interlocking interests of individual property rights, ineffective government, and a corporate-dominated economy. With people of color now the majority in the state, and expected to reach two thirds around the year 2020, this strategy may no longer be viable for controlling government. The emergence of the ‘corporate Democrats’ or ‘mod squad’ may represent a new strategy of corporate elites. Corporations like Chevron, Walmart, and realtors and hospital owners moved $9 million over to the group of Democrats over the last five years.27 The funds were used to support candidates like Jim Cooper and Cheryl Brown, both African American Democratic legislators who took the oil corporations’ side against climate change policies. The narrative of this emerging alliance is not established like the dominant narrative of the past thirty years, but it is surely in the works.

STRATEGIC LESSONS

In summary, California had a well-resourced government that created an infrastructure for opportunity through massive investments in education, housing, and other areas, but it did so in a racially exclusive way. When African Americans, Latinos and Asian Americans began demanding access, political leaders exploited racial anxiety by scapegoating people of color. They took advantage of increased racial anxiety, fostered racial resentment, and used dog whistle politics to capture government and shape the dominant narrative that government is ineffective and the market is our solution.

Once they had captured government, they re-wrote the rules to benefit the wealthiest over everyone else.

In tandem with the political developments, deindustrialization replaced high-wage factory jobs with low-wage service and retail jobs, gutting the wage and wealth gains of the working class in California. The high tech industry did not produce the abundance of high skilled, high paying jobs predicted and the financial sector created immense wealth for corporate elites by extracting wealth from working families.

This is the essence of how California came to have the toxic inequality and racial exclusion it has today. Much of what happened in California over the last forty years has more recently started happening across the country. Shifts in California’s racial composition between 1980 and 2000 are an indication of what the US will experience between 2000 and 2040.28 Political leaders across the country, like Donald Trump, are stoking white resentment and focusing it on immigrants and people of color as a strategy for taking over government and hoarding wealth at the top.

Going forward, California has the opportunity to provide the example for the nation on how this path only leads to a broken educational system, extreme inequality, and stifled opportunity and a lesson on how to build an inclusive democracy and a shared economy.

But the shifting corporate alignments in California and the lack of a coherent narrative for progressive change pose obstacles to converting a people of color majority and widely held progressive values into progressive governance and a fair and inclusive society.

Eli Moore is Program Manager for the Haas Institute’s strategic partnerships with grassroots community-based organizations.

Gerald Lenoir is the Identity and Politics Strategy Analyst working with the Haas Institute’s Network for Transformative Change.

This essay was created by the Blueprint for Belonging project, to find more videos, essays, podcasts, and our California survey on othering and belonging from this series click here.

- 1University of Southern California Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences/Los Angeles Times Poll (February 27, 2015) http://www.gqrr.com/articles/2015/2/26/new-university-of-southern-calif…

- 2Pastor, Manuel (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 14

- 3California Policy and Budget Center (Sept, 2016) "New Census Figures Show that Too Many Californians are Struggling to Get By", http://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/new-census-figures-show-many-calif…

- 4Public Policy Institute of California (May, 2012) “Defunding Higher Education What Are the Effects on College Enrollment?” http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_512HJR.pdf

- 5Sides, Josh (2004) Straight Into Compton. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/172853#top

- 6Zacchino, Narda (2016) California Comeback, pg 137

- 7 a b Field Research Corporation (2009) The Changing California Electorate. http://www.field.com/fieldpollonline/subscribers/COI-09-Aug-California-…

- 8Hosang, Daniel Martinez (2010) Racial Propositions

- 9Hosang, Daniel Martinez (2010) Racial Propositions, pg 115

- 10Brilliant, Mark (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 57

- 11Brilliant, Mark (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 54-55

- 12 a b Benner, Chris (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series

- 13California Department of Social Services (2000) Demographic Trends in California, http://www.cdss.ca.gov/research/res/pdf/multireports/DemoTrendsFinal.pdf. Public Policy Institute of California (2013) Immigrants in California, http://www.ppic.org/main/publication_show.asp?i=258

- 14Pete Wilson 1994 television ad supporting proposition 187, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLIzzs2HHgY

- 15Walker, Richard (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 37

- 16Haney-Lopez, Ian (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 32

- 17California Budget and Policy Center (April, 2015) “Who Pays Taxes in California?” http://calbudgetcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Who-Pays-Taxes-in-CA_Issu…

- 18Zacchino, Narda (2016) California Comeback. pg 87

- 19Schrag, Peter (1998) Paradise Lost

- 20Schrag, Peter (1998) Paradise Lost. pg 95

- 21Haas Institute analysis of data from California Department of Finance Historical Chart C-1, Program Expenditures by Fund, http://www.dof.ca.gov/budget/summary_schedules_charts/index.html and National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, Table 236.70. Current expenditure per pupil in average daily attendance in public elementary and secondary schools, by state or jurisdiction: Selected years, 1969-70 through 2012-13. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_236.70.asp?current=…

- 22Pastor, Manuel (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 18

- 23Zacchino, Narda (2016) California Comeback. pg 91-105

- 24Carr, Jim (2012) Wealth Stripping. http://democracyjournal.org/magazine/26/wealth-stripping-why-it-costs-s…

- 25Temple, James (May 7, 2009) "California was subprime central". San Francisco Chronicle, p. A-1.

- 26Pew Research Center (July 26, 2011) “Wealth Gaps Rise to Record Highs Between Whites, Blacks, Hispanics” http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/07/26/wealth-gaps-rise-to-record-hi…

- 27Data from the California Secretary of State on contributions to Californians for Jobs and a Strong Economy PAC, 2011-2015, http://powersearch.sos.ca.gov/advanced.php. See also Rosenhall, Laura (2015) “Rise of the Business Democrat”. https://calmatters.org/articles/rise-of-the-business-democrat/

- 28Pastor, Manuel (2016) Blueprint for Belonging series, pg 12