In the wake of the uprisings this past summer, public surveys show that Americans have a greater appreciation of the reality and extent of what is sometimes called “systemic racism,” or the ways in which institutional arrangements and societal structures produce racial disadvantage. Examples of this abound in health care, education, and the criminal justice system.

One of the streams of thought that has arisen out of this awareness is the necessity of race-conscious policy remedies to solve structural racism. It is claimed, and not without merit, that you can’t solve racial inequality with universal policymaking. As Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and 1619 project lead Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote on Twitter, “You can’t use race-neutral policies to fix race-specific harms.” As she noted, universalistic policies can reduce racial disparities, but they also maintain them.

In California, public authorities and policymakers are strictly forbidden from considering race in policymaking in the areas of employment, contracting and education. This prohibition was the culmination of a nationwide, multi-pronged effort to roll-back affirmative action in higher education and attack race-conscious remedial policies, such as set-asides and contract money for minority- and women-owned businesses.

In California, this effort was spearheaded by UC Regent Ward Connerly. In 1995, he and his allies successfully petitioned to have an amendment to the California Constitution placed on the 1996 state ballot. This referendum, known as the “The California Civil Rights Initiative,” was labeled Proposition 209. This ballot initiative passed with 54 percent of the vote, and had been championed by then-Governor Pete Wilson. Exit polls showed that 48 percent of women voted for it, as did 26 percent of African-Americans and 24 percent of Latinos. Post-election interviews suggested that people were misled and confused as to its purpose and ultimately effect, which may have contributed to its passage.1 With its passage, Proposition 209 became Article 1, Section 31, of the California Constitution.

The proposition contained eight paragraphs, but the main provision declares that “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.” State and federal law already provided strong protections against discrimination on these bases (race, sex, etc.). The critical clause is the language “or grant preferential treatment to.” This clause makes clear that the provision differs from prevailing federal and state anti-discrimination and equal protection jurisprudence.

Whereas the United States Constitution prohibits intentional racial discrimination for invidious reasons, it allows a small zone for preferential treatment on the basis of race through the use of a racial classification, as long as the policy at issue is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling governmental interest. This limited zone of permissible activity is eliminated under Proposition 209. This is the chief difference between the equal protection clause and Prop 209. The latter clearly prohibits what the federal equal protection clause narrowly permits.

Having the power and authority to do a thing does not require the exercise of that power. But it seems clear that taking away that power binds the hands of representatives and policymakers to address one of the most important issues of our time, systemic racism. Racial disparities in well-being (vividly illustrated by the Covid-19 pandemic), wealth, incarceration, and employment, among other areas, illustrate the need to at least consider race as one factor in policymaking.

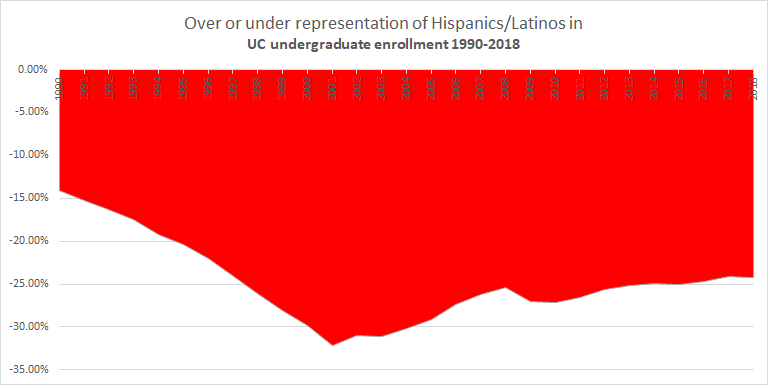

For example, the Hispanic non-white population of California has grown enormously in the past few decades, so that Latinx people are now a near-majority of the state’s college-age population (48.62 percent). Yet they were only 24 percent of the UC enrollment in 2018, an underrepresentation of nearly 25 percent.

Similarly, African Americans are nearly 6 percent of the state’s population, but just 4 percent of UC undergraduate enrollment, a relatively small underrepresentation in absolute terms, but nearly 30 percent in relative terms.

One of the ways that structural racism operates is to sort people on the basis of race into more or less disadvantaged communities, neighborhoods and schools. This is one of the reasons that the College Board, which administers the SAT, had proposed an “Adversity Score,” which would have quantified disadvantage. After considerable blowback, this plan was shelved. Consideration of race, in combination with other factors, can work similarly.

Part of the challenge is that the state of California has invested more in prisons than in higher education in the last 40 years. This has created scarcity at a time that California’s youth have grown, with more students chasing fewer spots on UC campuses. To build a more inclusive and equitable California, we need to do more than restore the power to engage in race-conscious policymaking, but we cannot do that without taking that step.

Editor's note: The ideas expressed in this blog post are not necessarily those of the Othering & Belonging Institute or UC Berkeley, but belong to the authors.

- 1A suit brought before the November election to compel the Attorney General to clarify that the law would ban affirmative action was unsuccessful, when an appellate court reversed such an order. People ex rel. Lungren v. Superior Court (1996) 926 P.2d 1042.