This week, Haas Institute Assistant Director Stephen Menendian and Senior Fellow Richard Rothstein with Coblentz Fellow Nirali Beri published a retrospective on the legacy of the Kerner Commission. The report, entitled “The Road Not Taken: Housing and Criminal Justice 50 Years After the Kerner Commission Report,” examines the nation’s progress in housing and criminal justice since 1968 and highlights areas where work remains. This blog, written by Beri, serves as a companion piece to that report, shedding light on a key moment of social transformation in the Bay Area that occurred just two years before the release of the Kerner Report—and the implications of this event for racial segregation and inclusion in the present day.

Over the last two decades, the Bay Area has experienced enormous demographic, technological, and societal changes that are largely due to the influence and growth of Silicon Valley. While newcomers may view San Francisco as a beacon of inclusivity, the city has a long history of racial segregation, discrimination and unrest that continues to have grave implications for communities of color today. The 1966 uprising in the San Francisco neighborhood of Hunters Point, and that community’s continued marginalization, is just one example of this history.

Hunters Point covers about five square miles in southeastern San Francisco. For more than a century, fisheries, slaughterhouses, and farmland dominated the land, before the neighborhood became a US Navy Shipyard in the late 1930s. During World War II, the Shipyard rapidly expanded in response to the national wartime effort. The Navy aggressively recruited from across the country, attracting tens of thousands of African American individuals and families fleeing the Jim Crow South, most of whom moved into poorly built dormitories and homes in Hunters Point. African Americans also occupied recently vacated rental homes in San Francisco’s Western Addition, after Japanese American tenants were forced out of their homes and into internment camps.

But after WWII the Shipyard’s labor force was severely reduced, the neighborhood unemployment rate shot up. While white workers were able to depart to suburbs, African Americans were disproportionately impacted by this economic shift because they remained isolated in Hunters Point as a result of racially discriminatory housing policies and practices in virtually every other region of San Francisco. At the same time, the African American workers and families who had lived in the Western Addition were forced out under the guise of urban renewal, and displaced to Hunters Point and neighboring Bayview. The buildings African Americans inhabited in Hunters Point, which were constructed as temporary housing for the Navy, deteriorated, marked by leaking roofs, sagging foundations, rotting plumbing, rodents, and other vermin. Toxic pollution, stemming from the disposal of radioactive materials from the Navy’s Defense Laboratory and other wartime waste, also plagued the region. The area was “devoid of amenities” like grocery shops and recreational facilities. Rampant police harassment further exacerbated the difficulties of African American Hunters Point residents. After a visit to Hunters Point in 1962, writer and activist James Baldwin called the neighborhood “the San Francisco Americans pretend does not exist.”

It was in this context that a white police officer killed Matthew “Peanut” Johnson, an unarmed African American 16-year old teenager, on September 28, 1966 near the Shipyard housing complex. Johnson had been joyriding in a car with two friends, Darrell Mobley, 14, and Clifton Bacon, 15. The car did not belong to the teenagers, although that fact was unknown to the police because the car had not yet been reported as stolen. When the teenagers were stopped by the officers, two of them fled the scene. The officer chased after Johnson and, from 250 feet away, shot at him. The officer’s fourth shot penetrated Johnson’s heart and killed him. After the incident the officer said that the initial three shots were intended to be warnings, but one witness said that all of the shots were aimed at Johnson.

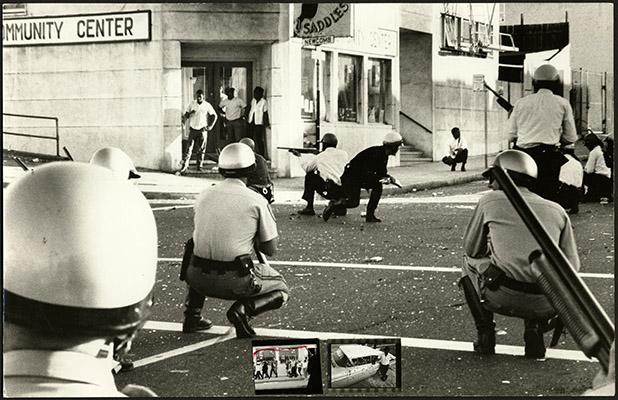

Less than two hours after Johnson’s death, dozens of upset and grieving members of the community gathered in the Shipyard, calling for the officer to be charged with murder. Some even discussed storming the Potrero Police Station. As people struggled to grapple with the violent act against Johnson, some community members reacted by throwing rocks, lighting fires and breaking into storefronts. Less than four hours after Johnson’s death, Governor Pat Brown called in the National Guard and Highway Patrol, summoning over 1,500 armed individuals to assist the local police. Law enforcement shot hundreds of bullets into the Bayview Community Center, only to find children and teenagers seeking shelter from the unrest there. In the three days following Johnson’s death, Governor Brown imposed martial law and curfews, and authorized armed National Guard members to patrol the streets, stating, “We cannot have revolution in this country and I can assure the people of my State that I will do everything within my power to see that law and order is observed and the rights of person and property are carefully protected. And I'll tell you this - we're going to meet force with force."

In the end, 457 people were arrested—only 129 of whom were white—and approximately $135,000 in property was damaged. Despite the community’s calls for justice, the officer who killed Matthew Johnson was eventually cleared of wrongdoing when the coroner found that the death was an “accident and misfortune” and therefore an “excusable homicide.” After a short term suspension the officer was was reinstated and given back pay.

While Johnson’s death was a catalyst for the Hunters Point uprising, many attributed the community’s response to underlying grievances, including joblessness, overcriminalization, inadequate access to education, and uninhabitable living conditions.

The public unrest in Hunters Point in response to the 1966 Johnson killing foreshadowed the more than 150 race-related uprisings across the US during the “long hot summer” of 1967, many of which were precipitated by police brutality against Black individuals. The events of that summer led President Lyndon B. Johnson to appoint a bipartisan group known as the Kerner Commission to investigate the underlying causes of the unrest. In a 600-page report, the commission published the US government’s most extensive assessment of racial inequality. The report acknowledged the interconnected nature of systemic discrimination and inequality and recommended full integration through targeted government investment in housing, education and employment programs, police reform, as well as increased availability of public benefits and services. But backlash to the Civil Rights Movement and the unavailability of discretionary federal funds due to the Vietnam War meant these calls for action were largely ignored.

As a result, more than 50 years after the Hunters Point uprising, African Americans in Hunters Point and across the Bay Area remain segregated and marginalized in similar ways. According to the 2010 US Census, the population in Hunters Point and its neighbor Bayview was 33.7 percent Black, compared to the 6 percent residing in San Francisco City and County as a whole. To make matters worse, the Bayview-Hunters Point African American population is plummeting, following the trend of the rest of San Francisco, due to skyrocketing housing costs and rapid gentrification. At the same time, the Bayview-Hunters Point community still faces severe environmental challenges resulting from the radioactive waste left by the Navy in conjunction with the waste from the PG&E power-plant that was in use until 2006. As a result of pollution, residents of Bayview-Hunters Point can expect to live 14 years less than individuals living in nearby San Francisco neighborhoods. Relatedly, the lack of access to healthcare also has severe consequences for Black families. In a city where African Americans make up around 5 percent of the population, 23 percent of all infant deaths were African American. As was the case in 1966, poverty remains a central issue for San Francisco African Americans, 20 percent of residents in Bayview-Hunters Point were living below the poverty level in 2016. Amidst this inequality, African Americans are over-policed, experiencing arrest rates 7.1 times higher than whites, accounting for 40 percent of arrests. Between 2005 and 2015, 33 percent of those killed by officers were African Americans.

San Francisco has all but realized the Kerner Commission’s ominous prediction that “Our Nation is moving towards two societies, one Black, one white – separate and unequal.” The calls for action in Hunters Point are as urgent today as they were in 1966.

Editor's note: The ideas expressed in this blog post are not necessarily those of the Haas Institute or UC Berkeley, but belong to the author.