< previous page | next page >

Considering the increasing number of explicit invocations of the Just Transition framework in the Global North, and because Global North collaborations with African countries and organizations are increasingly taking shape under this banner, we first focused on where in Africa the JT framework is used, by which African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations, and in what sectors.

Methodology

In addressing these questions of where in Africa the Just Transition framework is used, by which African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations it is used, and in what sectors it is used, we employed the methods of online content analysis. We looked for explicit references to JT on organizations’ websites and in their media materials. We also looked for explicit references to other climate action frameworks, such as Sustainable Development (SD). Finally, to further contextualize the use of such frameworks, we looked for references to the fossil fuel industry and impacts affecting their countries and populations of concern.

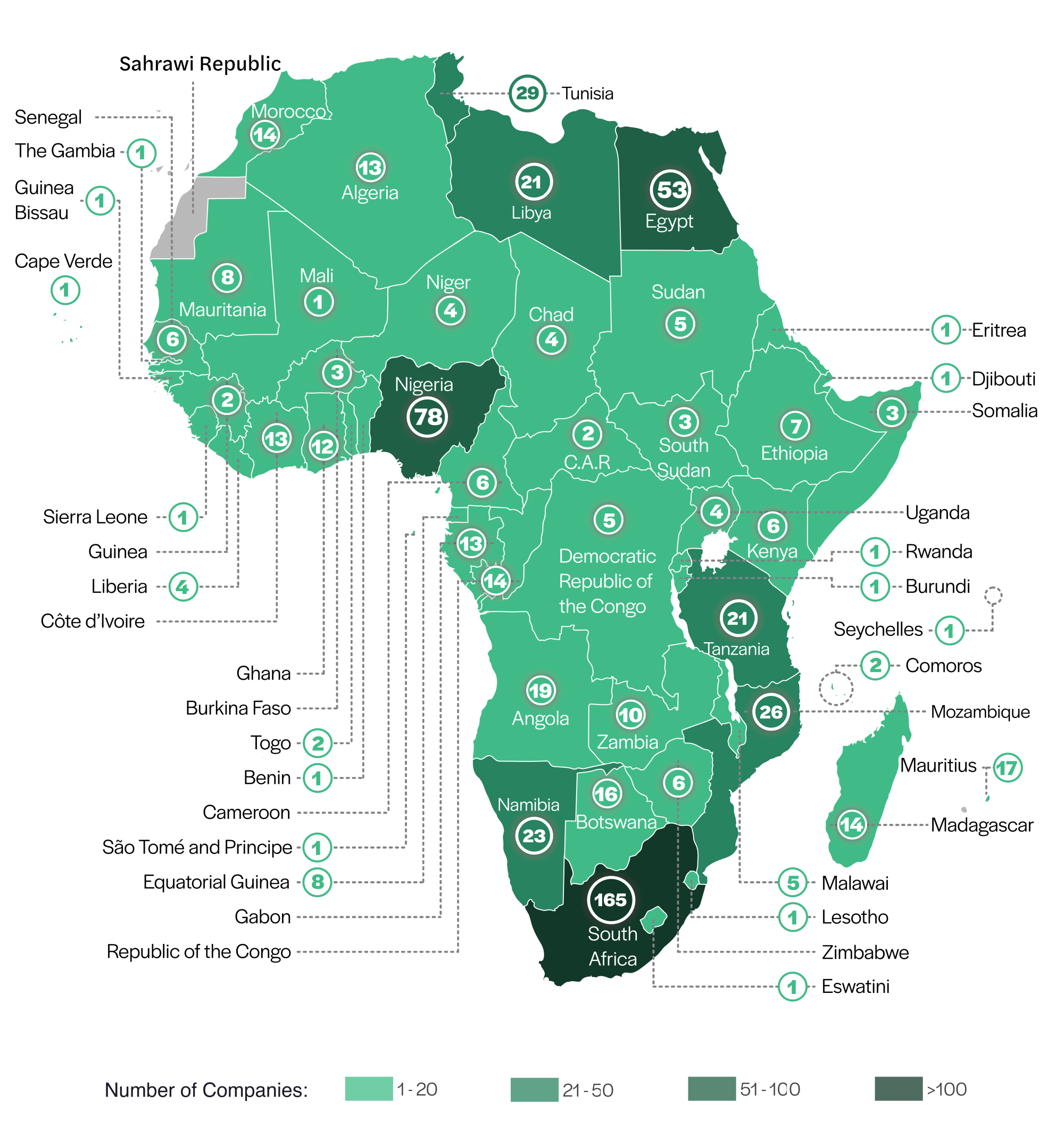

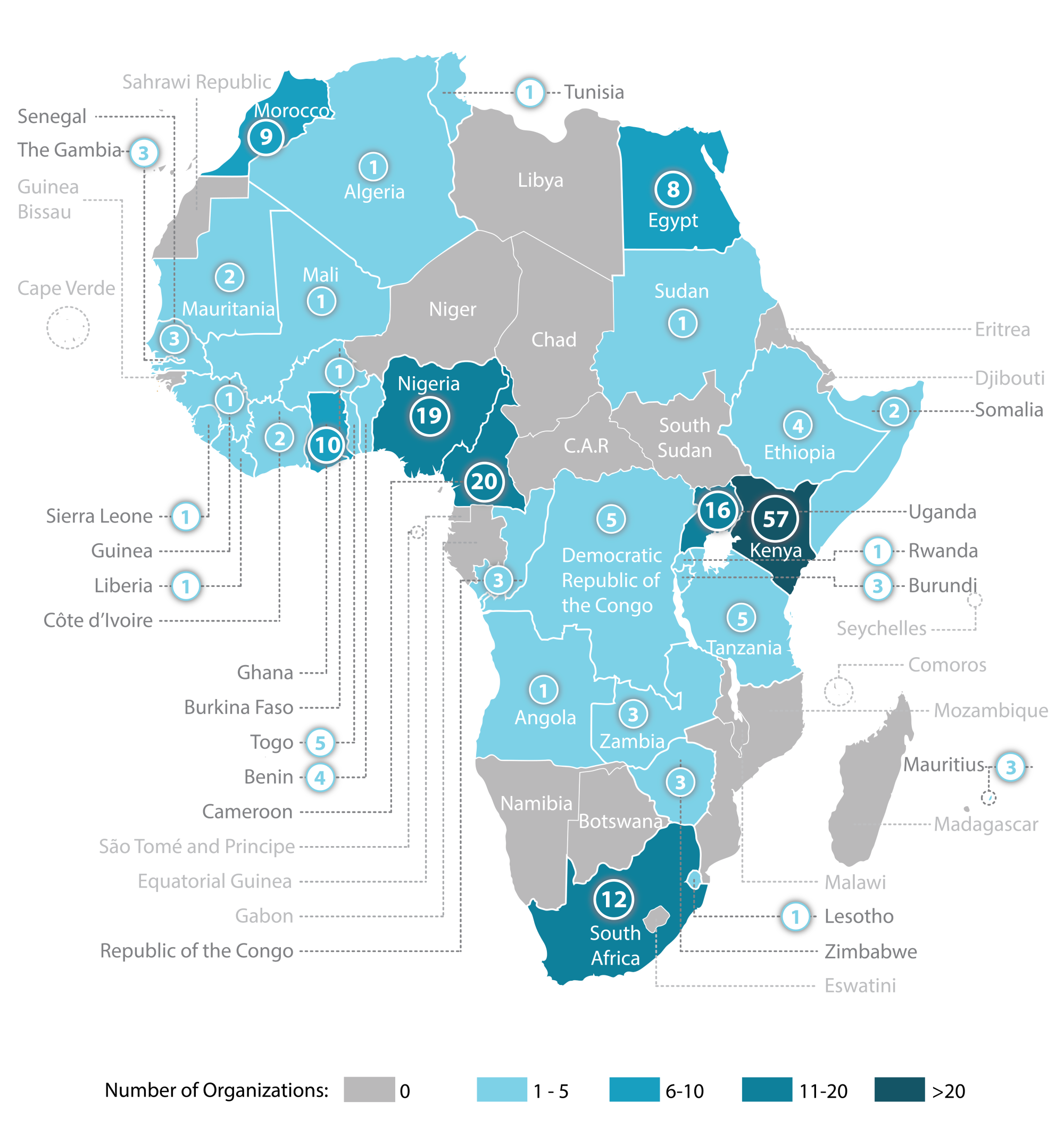

Deciding which organizations to focus on proved to be a challenge. There are countless climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations in Africa, many of which are very small and have a limited internet presence. We began research by referring to databases managed by large international organizations. The two databases we focused on were the UN Development Programme’s list of Accredited African Environmental Organizations, and the list of partner organizations operated by Afrika Vuka, a platform managed by 350Africa that works towards a “fossil free World.”7

Each of these lists includes many organizations that had no websites, social media pages showing very little activity and engagement, and in some cases no internet presence at all. Thus, part of this research involved determining which organizations were defunct and focusing efforts on larger organizations that seemed to be more active and have greater presence and more influence. One challenge of this approach—reflecting the limited tools at our disposal in this first stage of research—was that many organizations with limited online or social media presence may actually have large memberships and accomplish a great deal of work.

In total, we researched 91 organizations spread throughout 25 countries, covering all five regions of Africa as defined by the African Union.8 This figure does not encompass the true range of African climate, agri-food, and environmental movements and organizations. Indeed, factoring in the organizations on the UN Environment Programme’s list of accredited organizations, which includes climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations, brings the total number of countries with such organizations to at least 37 countries out of the 55 African Union member states.9

Of the organizations researched at this phase, the most represented countries were Nigeria (9 organizations), Senegal (7 organizations), South Africa (7 organizations), and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (6 organizations). Many of these organizations identified themselves as based in national capitals and other major metropolitan centers like Cape Town and Lagos. Additionally, many of these organizations operate networks of smaller grassroots organizations with agendas that address the severity and diversity of environmental, agri-food, and climate problems facing African communities.

Findings

In our online content analysis, we found that the Just Transition framework is not explicitly referenced among most of the African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations we studied. The prevalence of explicit references to the Just Transition framework corresponds with a nation’s degree of industrialization, and with organizations that focus on energy more so than other sectors. Despite this, we found that all the organizations we studied employ multiple principles, processes, and practices (e.g., sustainable development, food sovereignty, agrarian reform) across multiple sectors in service of just transitions—that is, building economic and political power to shift from extractive economies to regenerative economies.

The prevalence of explicit references to the Just Transition framework corresponds with a nation’s degree of industrialization, though just transitions strategies are employed across Africa

South Africa and Nigeria: Within Africa, explicit reference to the JT framework is most prominent in South Africa. Part of what may explain this fact is that South Africa is by far the largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter on the continent. In terms of emissions, it more closely resembles Global North countries than other African countries, as reflected in its having entered a just energy transitions partnership with the European Union, France, Germany, and the United States.10 Outside of South Africa, the JT framework also appears in Nigerian labor organizations, which is likely due to the prominence of the Nigerian hydrocarbon industry.

In other countries with lower GHG emissions than South Africa, and less prominent hydrocarbon industries than Nigeria, explicit references to the JT framework are rare (but by no means nonexistent). Although the JT framework is an umbrella framework spanning multiple principles, processes, and practices, its limited use elsewhere may be explained by the fact that most African countries do not have large hydrocarbon industries and contribute a very small share to global GHG emissions, with Africa as a whole accounting for 3.8 percent of global GHG emissions.11

Across Africa: Although the JT framework does not figure prominently in the work of most organizations in Africa, it appears in the platforms of a few organizations established to address climate crisis causes and impacts on the continent (e.g., 350Africa). It is important to note, however, that this does not mean that African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations in less industrialized countries are not concerned with Just Transition—only that the JT framework appears to be an especially effective way to emphasize and work on reducing atmospheric carbon and transforming existing hydrocarbon industries in particular.

Other frameworks, notably sustainable development and environmental justice, are referenced far more often by African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations. As laid out in the demands offered by such organizations, projects directed at energy transition are less centered on reducing atmospheric carbon, and more centered on securing energy access to greater segments of the population and mitigating the effects of the climate crisis, such as by reducing deforestation caused by fuel extraction and eliminating the public health risks posed by fossil fuel extraction and use.

By centering Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), sustainable development frameworks emphasize the reciprocal linkage between fostering socio-economic growth and ameliorating and preventing environmental crises. Throughout the continent, many organizations are committed to these objectives, while placing less emphasis on the decarbonization that the JT framework is often used to advocate for. Thus, regardless of the overarching framework used, all the organizations we studied employ multiple principles, processes, and practices across multiple sectors in service of just transitions in Africa.

The prevalence of explicit references to the Just Transition framework corresponds with—but is not limited to—organizations that focus on the energy sector

South African and Nigerian Organizations: Among the organizations researched, explicit references to the JT framework were primarily by organizations working on greenhouse gas emissions, fossil fuel extraction, and decarbonization. Given South Africa’s status as the largest GHG emitter on the continent, and given Nigeria’s large hydrocarbon industry, it came as no surprise that organizations which named the JT framework were by and large based in these countries.

The most prominent group that explicitly uses the JT framework is 350Africa, which is a South African network-based organization that organizes campaigns and events with local partner organizations. Its work is oriented towards instituting 100 percent renewable energy and ending future fossil fuel development. Similarly, the South African environmental organization Life After Coal is committed to reducing the burning and mining of coal, of which South Africa is the seventh largest producer in the world.12 The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) also advocates for a Just Transition structured around the needs of workers.13

The two Nigerian organizations that explicitly referenced the JT framework in official media are large labor organizations. In April 2022, the Nigeria Union of Petroleum and Natural Gas Workers (NUPENG) hosted a conference with the theme “Just energy transition for oil and gas workers, social welfare and security.” In remarks at the conference, the president of NUPENG stated the following: “There is a need to transition to more sustainable energy sources for both domestic and international production. Importantly, the global trade union movement is demanding a just transition that will take into cognizance the socio-economic impact on working people.” The regional secretary of IndustriALL, the global union of which NUPENG is an affiliate, followed up these remarks by recalling the trade union origins of JT and the necessity of orienting just energy transitions around workers’ needs into just energy transitions.14

The second Nigerian organization, the Nigerian Labor Congress (NLC), has a research department that lobbies the Nigerian government on just transitions.15 NLC works in partnership with Friends of the Earth to promote climate crisis awareness and advocate a worker-centered Just Transition in Nigeria. Both NUPENG and NLC mention JT specifically in reference to energy transitions and decarbonization. However, they do so from a position that acknowledges the economic significance of the present fossil fuel economy to the people who work in it. They frame clean energy as deeply connected to the wellbeing of workers, particularly those in Nigeria’s huge hydrocarbon industry.

Organizations Across Africa: Outside of South Africa and Nigeria, the one organization we found that explicitly mentions the JT framework is the North African Network for Food Sovereignty (Siyada), which is active in the region and works with other organizations throughout Africa and West Asia. Siyada is notable in using the JT framework to discuss food sovereignty by advocating for what it refers to as a “just agricultural transition.”16 Siyada frames food sovereignty—which encompasses multifaceted struggles to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis, reduce agricultural dependency on large corporations and foreign capital, and foster regenerative agriculture—as a component of just transitions, highlighting the multiple principles, processes, and practices that African organizations employ to foster just transitions.

Siyada is tied to the prominent organization La Via Campesina, which explicitly references the JT framework to advocate for sustainable agriculture, peasant rights, and an end to GHG emissions.17 Siyada’s work, and the work of related organizations which are partners of La Via Campesina, show how the JT framework encompasses social and environmental concerns that are not necessarily centered on energy production and GHG emissions. This employment of the JT framework demonstrates the expansiveness of the framework and suggests that much social and environmental justice work undertaken by organizations that do not explicitly use the JT framework can be regarded as work that fosters just transitions. Outside the NGO sector, the powerful African Development Bank advocates for an “inclusive just transition” that prioritizes women’s rights and needs.18

International Organizations: Besides organizations that explicitly reference the JT framework, several organizations are involved in work carried out by international organizations that explicitly references the JT Framework. These include groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Togo, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique which were partners in the report “Locked out of a Just Transition: Fossil Fuel Financing in Africa,” co-authored by the British organization BankTrack and the Dutch organization Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth Netherlands).19

Notably, several African branches of Friends of the Earth, including those in Mozambique, Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo, were involved in that report and another report which explicitly references the Just Transition framework supported by Milieudefensie.20 These organizations provided information about foreign-funded fossil fuel projects in Africa to the European authors of these reports. The contributions made by these organizations highlight the social, economic, and environmental harm caused by foreign-funded fossil fuel extraction projects, thus decentering emissions and incorporating a focus on more localized consequences of fossil fuel economies imposed by wealthy foreign interests on African communities.

Although they do not explicitly reference the JT framework, all African organizations employ principles, practices, and processes that foster just transitions, and do so in service of key populations

In reviewing the websites of many African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations, we found that the language of sustainable development is the primary means through which organizations voice the connections between economic growth and environmental protection that are key to fostering just transitions. To such organizations, facilitating economic growth and ameliorating and defending against environmental degradation are mutually supportive missions. Such organizations articulated these principles, processes, and practices by focusing on agrarian and rural livelihoods, women, and youth.

Agrarian-centered Organizations and Campaigns: Common missions structured around economic and environmental considerations include improving food security, fighting for women’s empowerment, and advocating for sustainable land management.21 African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations tend to orient their activism around the economic, social, and physical wellbeing of communities, with much work focused on rural areas that rely on agriculture. Many organizations advocate for involving rural communities in decision-making processes relating to agriculture and land management.

Organizations like Amis de la Terre - Togo work closely with village communities to implement solutions to local problems affecting rural villages or groups of villages.22 Across the border, Amis de l’Afrique Francophone - Benin (AMAF - Benin) works with indigenous peoples and local communities to develop sustainable natural resource use and conservation strategies under the banner of “Community Forest Management.”23 AMAF - Benin’s pledge to work with local communities reflects a commitment to grassroots organizing and community economic well-being. This commitment is widespread among African environmental, agri-food, and climate organizations.

Organizations often advocate for a combination of technological, social, and political approaches to addressing environmental problems. This is the case of Senegalese organization Action Solidaire International (ASI), whose projects include introducing modern fish-smoking equipment to improve the working conditions of the women involved in this occupation, and lobbying the government to cease developing coal-fired power plants.24 Similarly, the Ghanaian organization Alliance for Empowering Rural Communities (AERCGH) advocates for the nationwide disinvestment from fossil fuel projects, and for access to climate- and health-friendly cookstoves in rural communities.25

Women-centered Organizations and Campaigns: ASI and AERCGH’s focus on food preparation technologies is indicative of a tendency among African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations to recognize a need to improve women’s economic and political conditions. ASI’s effort to disseminate fish-smoking equipment happens under its Women’s Economic Empowerment Support Project (Projet d’Appui à l’Autonomisation Économique des Femmes). Other organizations focus more explicitly on women’s empowerment. The multinational African Women’s Sustainable Development Network (Réseau Femmes Africaines pour le Développement Durable [REFADD]), which has branches in 10 central African countries, aims to foster women’s role in natural resource management, with the end of promoting their autonomy and improving their living conditions.

REFADD asserts that gender equity is a fundamental component of sustainable development.26 This assertion seems particularly urgent in light of what the African Development Bank characterizes as women’s central roles in African economies, where they work as farmers, entrepreneurs, and owners of one-third of the continent’s business, in addition to performing the vast majority of reproductive labor.27 In light of this widespread gender structure of African socio-economic life, many organizations whose work is concerned with the connections between the environment and the economy pay particular attention to the linkages between women’s socio-economic status and environmental concerns.

Like the Women Environmental Programme’s advocacy of Nigeria’s National Action Plan on Gender and Climate Change, and Action Solidaire International’s “deCOALonize” campaign in Senegal, much activism is directed towards national governments and aims to change policy. Organizations hold protests, send letters to executives and legislatures, and produce research reports directed at policymakers. One such example of policy advocacy is the Ghana-based Center for Climate Change and Food Security’s letter to the Ghanaian National Biosafety Authority, protesting that authority’s decision to approve the release of genetically modified cowpeas without sufficient community consultation.28 This is an instance of an NGO trying to hold a government accountable to local agricultural communities.

Youth-centered Organizations and Campaigns: Optimism about the energy and potential of young people runs high. In the continent with the youngest population, many climate, agri-food, and environmental, agri-food organizations consider youth an integral part of their constituency or have a component of their mission specifically directed at young people. Initiatives to educate young people about environmental risks and strategies of individual and collective action come up frequently in organizational literature across the continent. For example, in a website post describing a program intended to teach agricultural management skills, the organization Hope Land Congo, of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, discusses young people’s potential to revolutionize the agricultural sector in the Great Lakes region.29

International Partnerships: Many African organizations work in partnership with and receive financial support from Global North institutions and organizations, and/or are members of international activist networks. Like the networks that bring together African organizations united by common missions, partnerships outside Africa contribute to many organizations’ emphasis on shared struggle spanning the above constituencies.30

Significance

The broad scope of anti-fossil fuel activism and African just transitions

Collectively, African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations employ multiple principles, processes, and practices that build economic and political power to shift from extractive economies to regenerative economies—that is, just transitions—regardless of the framework they use. Advocacy around the transition to clean energy and the reduction of fossil fuel production and usage is a key way such efforts are advanced across the continent, as seen in the anti-fossil fuel organizing and activism led by African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations.

This organizing and activism is not just about reducing GHG emissions, but also about securing energy access and reducing the harm caused by fossil fuel extraction—both to the localized harms of extraction and the harms of GHG emissions globally.32 For example, Friends of the Earth - Togo provides an account of their campaign against oil exploration in cooperation with residents of a coastal village called Doevi Kope. Residents of this village noted the fact that oil exploration disrupted fisheries, contributed to coastal erosion, poisoned farmland, and caused illness.

Mozambican organization Justiça Ambiental (JA!), which contributed to the report “Locked out of a Just Transition: Fossil Fuel Financing in Africa,” is concerned with similar effects of the fossil fuel industry. The organization’s executive director, Anabela Lemos, argues that “Mozambique and its people are in the tragic situation of being devastated by both the causes and effects of the climate change crisis”—namely, conflict and exploitation associated with increased gas drilling, and extreme weather events aggravated by the climate crisis.33 Such organizations recognize the links between justice, wellbeing, and a fossil fuel-free world.

As seen in the ways that Nigerian labor organizations center the welfare of workers, African climate, agri-food, and environmental organizations simultaneously advance decarbonization and foster the economic wellbeing and political rights of Africans in places where fossil fuel industries are both a source of jobs and a source of harm. Collectively, African organizations highlight and address the harms of extractive, fossil fuel-based economies—spanning the dispersed effects of GHG emissions, and the effects of fossil fuel extraction on local communities—as well as the regenerative economies that must follow.

< previous page | next page >

- 7 Afrika Vuka. “About.” https://afrikavuka.org/about/.

- 8 “Member States.” African Union. https://au.int/en/member_states/countryprofiles2.

- 9 “List of Accredited Organizations.” UN Environment Programme. https://www.unep.org/civil-society-engagement/accreditation/list-accredited-organizations.

- 10 “France, Germany, UK, US and EU launch ground-breaking International Just Energy Transition Partnership with South Africa.” European Commission. November 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_5768.

- 11 “Africa in Search of a Just Energy Transition.” African Development Bank Group. December 2021. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/africa-search-just-energy-transition-47252.

- 12 “Annex to the G7 Leaders Statement Partnership for Infrastructure and Investment.” G7. 2021.

- 13 “Just Transition: Blueprint for Workers Summary Document.” COSATU. 2022. http://mediadon.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/COSATU-Just-Transition-Blueprint-Full-version.pdf

- 14 “What Would a Just Transition in Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Sector Look Like?” IndustriALL Global Union. April 2022. https://www.industriall-union.org/union-discusses-a-just-transition-in-nigerias-oil-and-gas-sector.

- 15 “Research Department.” Nigeria Labour Congress. https://www.nlcng.org/research-department/.

- 16 “A New Study: Towards a Just Agricultural Transition in North Africa.” Siyada. 2022. https://en.siyada.org/siyada-board/research-and-publications/studies/new-study-towards-a-just-agricultural-transition-in-north-africa/.

- 17 “Land Workers of the World Unite! Food Sovereignty for Climate Justice Now!” La Via Campesina International Peasants’ Movement. 2021. https://viacampesina.org/en/land-workers-of-the-world-unite-food-sovereignty-for-climate-justice-now/.

- 18 “Inclusive Just Transition.” African Development Bank Group. https://www.afdb.org/en/initiatives-partnerships/climate-investment-funds-cif/just-transition-initiative-address-climate-change-african-context/inclusive-just-transition.

- 19 “Locked Out of a Just Transition: Fossil Fuel Financing in Africa.” Oil Change International, BankTrack, and Milieudefensie. 2022. https://priceofoil.org/2022/03/03/fossil-fuel-financing-in-africa/.

- 20 “A Just Energy Transition for Africa? Mapping the Impacts of ECAs Active in the Energy Sector in Ghana, Nigeria, Togo and Uganda.” Abibiman Foundation Ghana et al., Ellen Lammers, ed. November 2020. https://www.bothends.org/en/Whats-new/Publicaties/A-Just-Energy-Transition-for-Africa---Mapping-the-impacts-of-ECAs-active-in-the-energy-sector-in-Ghana-Nigeria-Togo-and-Uganda/.

- 21 “About Us.” Centre for Climate Change and Food Security. https://cfccfs.org/about-us.; Centre for Alternative Development. https://www.cefadev.org/; Hope Land Congo. https://www.facebook.com/HOPELANDCONGO/.

- 22 “Nos Actions à Fiopko.” Les Amis de la Terre-Togo. https://www.amiterre.org/suivie.

- 23 Amis de l’Afrique Francophone Benin. https://amafbj.wixsite.com/amafbj.

- 24 “PAAEF : Projet d’Appui à l’Autonomisation Economique des Femmes.” Action Solidaire International. https://action-solidaire.org/paaef-projet-dappui-a-lautonomisation-economique-des-femmes/.

- 25 “AERC - Ghana.” Alliance for Empowering Rural Communities. https://aercgh.org/.

- 26 “Présentation du REFADD.” Réseau Femmes Africaines pour le Développement Durable. http://www.refadd.net/qui-sommes-nous/test-page/.

- 27 “Empowering African Women: An Agenda for Action.” African Development Bank Group. 2015. https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/topics/quality-assurance-results/gender-equality-index.

- 28 “CCCFS Seeks Information on GMO Cowpea Assessment.” Ghanaian Times. August 30, 2022. https://www.ghanaiantimes.com.gh/cccfs-seeks-information-on-gmo-cowpea-assessment/.

- 29 “Les Jeunes de la Région des Grands Lacs Prennent l’Engagement d’Assurer la Sécurité Alimentaire dans cette Région.” Hope Land Congo. 2021. https://www.facebook.com/HOPELANDCONGO/posts/2192287327592285.

- 30 See: “What We Do.” 350Africa. https://350africa.org/about/what-we-do/.

- 32 Maclean, Ruth, and Dionne Searcey. “Congo to Auction Land to Oil Companies: ‘Our Priority Is Not to Save the Planet.’” The New York Times, July 24, 2022, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/24/world/africa/congo-oil-gas-auction.html.

- 33 “At least $120 Billion in Finance for Fossil Fuels are locking Africa out of a Just Transition, shows new Report.” JA! Justiça Amiental. March 2022. https://ja4change.org/2022/03/25/at-least-132-billion-in-finance-for-fossil-fuels-are-locking-africa-out-of-a-just-transition-shows-new-report/.