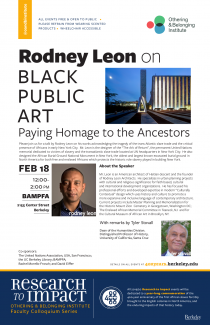

Leon is the designer of the “The Ark of Return,” the permanent United Nations memorial dedicated to victims of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade located at UN headquarters in New York City. He also designed the African Burial Ground National Monument in New York, the oldest and largest known excavated burial ground in North America for both free and enslaved Africans which protects the historic role slavery played in building New York.

This talk was part of the Othering & Belonging Institute's Research to Impact series, which has dedicated all of its 2019/2020 talks to the 400 Years of Resistance to Slavery and Injustice Initiative.

Other sponsors of this talk included the United Nations Association, USA, San Francisco; the UC Berkeley Library; BAMPFA; Rachel Morello-Frosch, and David Eifler.

Check out this page to download a flier of the event.

Transcript:

Leigh Raiford:

My name is Leigh Raiford, I'm an associate professor of African American studies here at UC Berkeley, and with Lauren Kroiz, associate professor of History of Art, and field faculty director of the Hearst Museum of Anthropology, I'm co-instructor of L&S 25, Public Art and Belonging. Today's event, Rodney Leon on Black Public Art paying homage to the ancestors, is the fifth in the series of public lectures and conversations organized as part of this course.Leigh Raiford:

In considering Public Art and Belonging, we first recognize that this class takes place on the ancestral and unceded land of the Ohlone, the successors of the historic and sovereign Verona Band of Alameda County. We recognize that every member of the Berkeley community has, and continues to benefit from the use and occupation of this land, since the institution's founding in 1868. We acknowledge and pay respect to Ohlone ancestors, peoples today, and the Ohlone future to come.Leigh Raiford:

So this lecture series and the course explores relationships between art and belonging, race and place, history, memory, and the imagining of just futures. We're thrilled to be partnering with UC Berkeley's Othering & Belonging Institute, formerly The Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, and their year-long commemoration of 400 Years of Resistance to Slavery and Injustice.Leigh Raiford:

I see some familiar faces from our previous talks, and if you hadn't seen one of the previous slides, we've had Paul Farber of Philadelphia's Monument Lab, author-activist and UC Berkeley alumnus Jeff Chang, Berkeley-based artists Lava Thomas and Mildred Howard. And last week, we welcomed SFMOMA, curator of contemporary art in Jeju. Unfortunately, this Thursday's talk by Sarah Lewis is canceled, Sarah Lewis is a Harvard professor of art history in African American studies, and the founder of the Vision & Justice Institute. She's unable to make it and so I should say yes, the lecture is canceled and L&S 25 class is also canceled. So catch up on your work, your reading, get your lives in order, you've been offered a reprieve, so extra time to work on your exhibition reports.Leigh Raiford:

However, our next public lecture, our next public event is Thursday, March 5th at noon, when we welcome Oakland-based artist, Sadie Barnette and San Francisco Experimental Space Program of Dena Beard. In the remainder of the semester, we'll be joined by Oakland-based artists, Jesus Barraza and Melanie Cervantes, founders of the Graphic Arts Collective, Dignidad Rebelde, Chef and James Beard, award-winner Bryant Terry, who has a new book, new cookbook, Alvin Ailey Dance director, Ronni Favors, Café Ohlone co-founders, Vincent Medina and Louis Trevino, artists Cannupa Hanska Luger in collaboration with the Arts Research Center, as well as San Francisco-based dance artist and director Gerald Casel, creative and executive directors of SOMArts Maria Jensen, and Playwright Dustin Chinn in collaboration with Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies who will be mounting Chinn's play with the best title, "Snowflakes or Rare White People."Leigh Raiford:

So in our final lap public lecture, students will present their own proposals for public art on Berkeley's campus. So of course, an undertaking of this magnitude would not be possible without generous financial, logistical, emotional support. The course, this course, L&S 25 falls under the division of Letters and Science, big ideas, moniker. And it's part of the series Thinking Through Art and Design at Berkeley. That series is supported by the office of arts plus design, a campus-initiative under the study and visionary leadership of Shannon Jackson, and the excellent administrative work of Paris Cotz and Soomin Suh.Leigh Raiford:

A+D connects and fortifies the creative life of departments, schools, centers, museums and student clubs throughout the Berkeley campus and in Bay Area regional collaboration. Arts plus design has spearheaded the Berkeley Arts Passport, which offers discount tickets to events on Berkeley students, mobile apps, and I think our class put a run on the SFMOMA ticket, so I apologize if we ran out of those.Leigh Raiford:

A+D also offers course grants and create a pedagogy, co-curator range of public lecture series including A+D Mondays, every Monday evening here at BAMPFA. All expenses for this course including our teaching, our graduate student instructors, our students' access to the arts, and this community lecture series is made possible by A+D, and by generous philanthropic donation, so we thank them.Leigh Raiford:

And we also thank the Othering & Belonging Institute, the sponsor of today's talk by acclaimed architect Rodney Leon. Today's event, as I mentioned, is a collaboration with the Otherness & Belonging Institute and their 400 years initiative, which is spearheaded by Dr. Denise Herd, and made possible by program assistance from Takiyah Franklin, faculty research cluster coordinator. All of their labor and sponsorship, not only made Rodney Leon's visit possible, but enabled us to open the Orchard Theater today, to the public today, which is generally closed on Tuesdays.Leigh Raiford:

But I do hope you'll come back because the Rosie Lee Tompkins' exhibition of quilts is opening tomorrow. So Dr. Herd, I'm going to hand it over to Dr. Denise Herd shortly. Dr. Herd is the institute's third associate director and is a longtime member of the institute's Diversity and Health Disparities research cluster, she's also an associate professor of public health here at UC Berkeley.Leigh Raiford:

Her scholarship centers on racialized disparities and health outcomes, spending topics as varied as images of drugs and violence and rap music, drinking and drug use patterns, social movements, and the impact of corporate targeting and marketing unpopular culture among African American youth. In addition to her extensive scholarship in public health, Herd has also served as associate dean at UC Berkeley's School of Public Health for seven years. So please join me in welcoming to the podium, Dr. Denise Herd, who will be facilitating today's event.Denise Herd:

Thank you so much, Leigh for that really kind introduction, and we are thrilled to be able to partner with Leigh and Lauren, and A&D in this course. It's a really special experience and I'm so happy and very honored to welcome all of you here to one of our first events of 2020 in our year-long commemoration of 400 Years of Resistance to Slavery and Injustice. And I think today's event is especially meaningful and exciting, because we have the opportunity to explore and reflect upon unique memorials dedicated to observing the ancestral past of Africans in our nation's history.Denise Herd:

Ironically, most of the monuments related to African American history in this country have been devoted to uplifting slaveholders and to commemorating the confederacy. So we have very few monuments examining the past from the perspectives of Africans, either exploring the tragedy of slavery or honoring Africans themselves, despite our extensive and critical contributions to building this nation. So we are really fortunate to feature a program with a really visionary architect who has tapped into the spirit of this past and help to memorialize it for all time.Denise Herd:

So the Othering & Belonging Institute, as you know is, we're cosponsoring this event and it's part of our research to impact series. But before we begin today's program, I'd like to begin thanking our generous co-sponsors who helped make this event possible. First as I said, we're thankful to professors Lauren Kroiz and Leigh Raiford, who are hosting this class and love the idea of collaborating with us to host Mr. Leon's talk. We're also grateful to BAMPFA, who's a major co-sponsor of the event as well as the Department of Arts plus Design, under the direction of Professor Shannon Jackson, and other groups and individuals who made special contributions to this event, include the library at UC Berkeley, David Eifler, Rachel Morello-Frosh, The Institute of European Studies, The United Nations Association of the USA, the San Francisco Chapter, and the United Nations Association of the East Bay Chapter.Denise Herd:

I'd also like to thank all of the other individuals including faculty and staff, who've helped support our program today. Paris Cotz, Soomin Suh, at A&D, Takiyah Franklin and Larissa Benjamin had been especially helpful with supporting the event, today's event.Denise Herd:

And now, it's my great pleasure to introduce Professor Tyler Stovall, who will provide a few remarks on the significance of the memorials designed by Mr. Leon from an historical and international perspective. So, Tyler Stovall is distinguished professor of history at the University of California, Santa Cruz, he's also the dean of the Humanities Division there, he's also taught at the Ohio State University and UC Berkeley.Denise Herd:

He recently finished the term as president of the American Historical Association, he specializes in the history of modern in 20th century France. Professor Stovall has written and edited several books on the subject including Paris Noir: African-Americans in the City of Light, and Transnational France: The Modern History of Universal Nation. He's currently writing a global history of the relationship between freedom and race titled, White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea, forthcoming from Princeton University Press. So now I'd like to welcome Tyler to the podium.Tyler Stovall:

Thank you, Professor Herd, and thank you all at Berkeley for putting together this program and for all the work that has been done in terms of commemorating the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first slaves and what was to become in United States. When I was very small growing up on an all black street in Ohio, there was a rumor that a house at the end of that street had been a stop on the underground railroad. Nobody ever bothered to authenticate that or sort of place it in official knowledge, but the rumor persisted, as do rumors of many other institutions involving black life and black history throughout the United States.Tyler Stovall:

So when we talk about memorializing this history, when we talk about creating public memorials to it, it is important to remember that this is a history that has in many ways been informally memorialized for many generations. And so, what our task is to bring together those informal memories, or in many cases, those African American memories with the public record, and with a public record of what? Not just African American history but American history in general has been.Tyler Stovall:

It is very exciting to have Rodney Leon here to talk about his work, and I wanted to put it in a bit of historical cont-- I'm sorry, I'm a historian, that's what I do, historical context. First of all, I wanted to say a couple of remarks about where his work fits into the broader history of blacks and slavery in the city of New York. Many Americans don't even realize that a city like New York was a slave center.Tyler Stovall:

For many Americans, slavery was something that was relegated to the south below the Mason-Dixon Line. They are often very surprised to learn that New York City was America's greatest slave port, second only to Charleston's South Carolina during the antebellum years. That New York City had a population of slaves that was so large, that at one point in the early 18th century, something like almost half of the households in New York had at least one black slave.Tyler Stovall:

That New York City is a city that has a history of anti-slave riots, and the oppression of those riots, the great rebellion of 1741, for example, which was bloodily repressed, was a slave rebellion. So in exploring the history of slavery in New York, it is important to underscore the fact that this was a major part of the city's history, a major part of the city's economy. One of the first slave markets in the city was actually founded on Wall Street, anyone could talk about the relationship between Wall Street as a slave center, and Wall Street as a financial center, which of course goes to the impact of slavery into generating the American economy as a whole in the 19th century.Tyler Stovall:

Now, in talking about this history, I want to talk about something that's both present and something that's absent, and I realized that I only have a few minutes, so hopefully I'll get to the absent part. But the presents I want to talk about is one of new York's greatest monuments, the Statue of Liberty. The Statue of Liberty is often associated with the history of immigration in the United States. You can see many, many images of immigrants from Europe coming into New York Harbor being welcomed by the Statue of Liberty, promising them freedom. And yet, there's also a side of the Statue of Liberty's history that deals with the fight against slavery.Tyler Stovall:

The Statue of Liberty was originally developed in France and conceived by Édouard de Laboulaye, one of the France's first specialist in American studies and a great scholar of the United States, who was also very demoted to the idea of democracy. When he conceived of the idea of the Statue of Liberty, he conceived of it as a statue that would commemorate not immigration, but rather the end of slavery, that America was finally a land of the free. And he wanted to design it in a way that would exemplify this tradition.Tyler Stovall:

So for example, the Statue of Liberty was originally designed, the original design had the Statue of Liberty holding broken chains in her hands. It also had the Statue of Liberty bearing a cap, it's known as the Phrygian cap, which is the ancient Roman symbol for freed slaves. Somehow, these dimensions got lost in translation, the Statue of Liberty that was finally built in New York Harbor, first of all, did not have the Phrygian cap, it does have changed but they are at the base of the feet of the statue, so unless you are in a helicopter, you will never see them.Tyler Stovall:

And then finally, there was the issue of the torch that the Statue of Liberty carries. The torch in a sense was initially supposed to be a symbol of revolution, the flames of revolution that illuminated slave revolts. And yet, precisely because it was such a revolutionary symbol, what you have, the Statue of Liberty is carrying, is a rather enclosed torch. As de Laboule himself said, "To illuminate, not to destroy." A symbol of enlightenment rather than revolution.Tyler Stovall:

So what you see as the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor represents a certain voyage away from the initial idea of it, and above all represents the fact that its roots in the anti-slavery movement have been hidden and have been ignored, and this is true to the present day.Tyler Stovall:

One of the things the Statue of Liberty does, to go back to the remarks I was making a moment earlier, was to hide the fact that many people that came to America came not as free immigrants but as slaves. It hides the fact that New York was one of America's great slave ports, and that the entry to New York Harbor was for many people as a situation of bondage rather than liberation. So that's the present I wanted to talk about.Tyler Stovall:

I want to also briefly talk about an absence or absences. Rodney Leon has done wonderful work in terms of trying to memorialize the history of slavery and of African American life in the United States, but it is no criticism of him at all to say that much, much more remains to be done. We have been commemorating this past year the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first slaves in the United States. Last year was also the centennial anniversary of what was known as the Red Summer of 1919. Not only one of the greatest periods of race riots in American history, but also the high point of lynching in the United States. More people of black people were lynched in 1919 than in any year, other year in American history before or since.Tyler Stovall:

So where are the memorials to this history? America is starting to develop these memorials, one area of I've worked on in particular was the small city of Elaine, Arkansas, which in the end of September 1919 was the site, first of all of a sharecropper's strike, a strike by black sharecroppers that turned into a racial massacre. Nobody knows how many black people died in that massacre over about three days, the best estimate is at least 250 people, maybe more like one person is estimated as many as 800.Tyler Stovall:

Just last year was the first time that anybody ever created a memorial to that history, next year we'll see the Huson centennial anniversary of the race riot of Tulsa. The destruction of what was known as the Black Wall Street, which again saw the massacre of several hundred African Americans, and that was memorialized starting about 10 years ago with the building of a plaque and then what was done was the tower of reconciliation.Tyler Stovall:

Now, I said I would speak about an absence, the greatest civil insurrection in American history other than the civil war itself, where the New York draft riots of 1863. When large white mobs, mostly Irish mobs, protesting against the imposition of the draft, rampage throughout the city of New York massacring blacks all over the city, all over Manhattan. In fact, expelling much of the black population from Manhattan.Tyler Stovall:

They did things like burn to the ground an orphanage for black youth, and hung and murdered at least 110 African Americans. To this day, to my knowledge, I mean, writing the Armenian at no different, there are no public memorials to the draft riots, there is no out, public out, either have been museum exhibits, but there is no permanent acknowledgement of this history in New York. So have a good visit, Mr. Leon because you've got a lot of work to do. Thank you.Denise Herd:

Thank you so much for those remarks, Professor Stovall, they were very interesting and inspiring. And now I'm very pleased and excited to welcome Mr. Rodney Leon, who is our keynote speaker for today's event to the stage. Mr. Leon is an American architect of Haitian descent and the founder of Rodney Leon Architects, he's the designer of the Ark of Return, the Permanent United Nations Memorial dedicated to victims of slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade located at the UN headquarters in New York City.Denise Herd:

He also designed the African Burial Ground National Monument in New York, the oldest and largest known excavated burial ground in North America for both free and enslaved Africans, which protects the historic role of slavery played in building New York City. Mr. Leon specializes in urban planning projects with cultural and religious significance for faith-based cultural and international development organizations. He has focused his professional efforts and developed expertise in modern culturally contextual design, which uses history and culture to promote a more expansive and inclusive language of contemporary architecture.Denise Herd:

Current projects include master planning and memorialization for the historic Mt. Zion Cemetery in Georgetown, Washington, the Enslaved African Memorial Committee in New Jersey, and the Cultural Museum of African Art in Brooklyn, New York. We became interested in Rodney's work while planning for the 400 years commemoration act activities, and we were immediately drawn to the very evocative Ark of Return that he designed. Subsequently, I had the chance to be in New York and the opportunity to meet him and also to see the Burial Ground itself and the amazing work that he's done. And I'm really glad we worked on this for a number of months that we were able to persuade him to come to California and share his perspective as a part of this important commemoration.Denise Herd:

We, on this campus have been talking for a year about what is it we can do for the campus to do a much better job of portraying our history and the contributions of African Americans to life here at Berkeley. So it means a great deal to have someone that's going to be in our presence who's worked so carefully to provide the respect and homage, do our ancestors that are rarely observed on this continent. And we had the opportunity this morning, we did a campus tour looking at black spaces on campus, and it was just a really great experience.Denise Herd:

So Rodney, if you would please, we'd like to welcome you to the stage, we look forward to your time.Rodney Leon:

Thank you, everyone. Well, first I'd like to thank you very much for having me here at Berkeley, this is only my second trip to the West Coast of the United States. Denise and some of the folks who invited me here were kind enough to give me a tour of some of the spaces and places throughout the campus that commemorate the impact and the influence and the contributions of people of African descent historically that have been made here on the campus of Berkeley.Rodney Leon:

And there are these like a kind of almost like jewels of spaces and places and people, that if you weren't given a tour and you were just given the opportunity to just tour Berkeley, you wouldn't be able to necessarily perceive or conceive of the extreme dedication and sacrifice of people that dedicated their life to education, to liberation, without having a much more of, I think a personal connection and a personal insight and somebody to be able to actually communicate that history to you.Rodney Leon:

Some of the places and spaces have exhibits tied to them, some of them like even the bookstore that we went by this morning which is celebrating black history month have even more comprehensive information about black history than even some of the historic places on the academic campus itself, which was kind of ironic but at the same time refreshing.Rodney Leon:

And I think that in a lot of ways, these spaces and these places that are dedicated towards memory, dedicated towards the sacrifices of the people that in many cases no longer with us are spaces of memorialization, spaces of acknowledgement, spaces of reflection. And because they're not necessarily permanent, as Tyler had said, they might not necessarily last beyond this kind of fleeting moment that we interact with them.Rodney Leon:

So I think that for myself, as a person of African descent, I've always been interested in delving into and utilizing architecture as a means of expression and a medium of expression to communicate and to understand more about history, about culture, and to create a kind of like a more permanent impact of the history and culture on public space. And to provide people the opportunity to engage and to create, I think a more inclusive understanding of people's experiences and their contributions to American history.Rodney Leon:

And that goes across a broad spectrum of contributions and experiences, because being born and raised in New York City, I didn't know anything about the African Burial Ground till I was in graduate school, ironically enough in university at Yale Graduate School of Architecture. And that was the time when the African Burial Ground was uncovered, I think in about 1993 or so.Rodney Leon:

And I felt that it was for me, somebody who had prided themselves as a young student and having a knowledge of African American history diaspora history to be born and living in a city for most of my life and not knowing about the existence of this Burial Ground that was right behind city hall was for me, a source of shock.Rodney Leon:

So I could only imagine like most people who think of New York City as being in it, is this kind of inclusive cosmopolitan city being the place, a center of slavery and a slave of that type of activity would be quite a shock to them. But nevertheless, it is part of our collective history, and it's something that people, I believe, especially young people need to understand and to put perspective on.Rodney Leon:

So what I'd like to do is to present to you some of the thoughts that I've had collected, as well as two of the projects that we've worked on related to these types of monuments. And the first is the African Burial Ground National Monument, which I just mentioned. The second is the monument at the United Nations, which is the monument to Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and also the victims of slavery.Rodney Leon:

So the first is really coming out of a series of ideas of what I call Culturally Contextual Landscapes, and these Culturally Contextual Landscapes, I believe are spaces that hopefully allow us to allow me to be able to understand the idea of what African American space or black spaces. And these are some thoughts and ideas that I've been ruminating about that deal with the idea of how to contextualize American cities and the American spaces so that they become more inclusive.Rodney Leon:

And I think that there always was and will be space that is was and will be space that is, was and will be primarily designed and constructed for and reflected or affected by the social economic and political relations called African American. And because of this, I ask myself questions like, "What are the processes that have been used to create these spaces, or can be used to develop such spaces? How does one construct space that can be identified as African-American?" And understanding of context is really critical, though I don't mean by what architects traditionally mean by context with that term, I do not mean the conditions that have to do with physical form or physical space.Rodney Leon:

I'm not really referring to physical environment necessarily, or the processes of mapping the empirical relationships that exist in a physical environment, but rather I'm talking about a more dematerialized context, I mean the less tangible elements of culture in history and society like arts, economics, religion. These are unseen, but nevertheless present aspects of architecture which can be used, I believe as tools to generate architectural narrative, specifically by and for people of African American descent to create African American spaces.Rodney Leon:

Cultural context as it pertained to the African American has often been under-emphasized and ignored, and I think there are two primary reasons for this. First, as an act of self-preservation on the part of African Americans, concealing one's context can ensure one's safety, hence you'll be able to survive Tulsa race rights. Second, the African American cultural context were obviously, I believe has been historically marginalized, most likely by those who are wishing to maintain power for the institutions of oppression and control.Rodney Leon:

As students and as architects and as citizens, if we are ignorant of these hidden contexts that we call African American, we risk obscuring or neglecting the potential for African American space. And like African American space, African American history has also been muted and dematerialized cultural contextuality that is attention paid to context in the fullest sense which reemphasizes, reconstructs and re-materializes is necessary today.Rodney Leon:

African American space, like African American history must not be seen as a separate from American or architectural history at large. It is a fundamental part of our collective consciousness and as well as our identity as Americans. In fact, African American space is inherently American, and in order for African American space to be considered, African American history and culture must be first acknowledged and understood. So re-materializing African American context in architectural form, in my sense, reveals that which has been concealed.Rodney Leon:

The power of architecture is to return to us our context, if it cannot return what was stolen, it can possibly establish the memory of that loss and pay tribute to the people's resilience. And only by identifying and recognizing this existence can African American space emerge from the limited and restrictive psychological confines of slavery and racism.Rodney Leon:

The African American cultural experience is one that is unique too, and as defined by the American experience, Africans were stolen to make America. And as a result, African Americans are in every way essential to what we name American. Stolen labor, skills and knowledge inform the building of everything from Southern slave plantations to the large cities of the East Coast.Rodney Leon:

Some manifestations and evolutions of African American culture are familiar to mainstream American culture. Consider the African American contributions to music from Negro spirituals to gospel, jazz, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, soul, funk, house and hip hop. Cultural anthropologists and historians have since illustrate the connections between these genres in the African oral tradition of call and response.Rodney Leon:

This demonstrates how rich histories can be referenced in cultural traditions reconfigured to operate under a set of conditions. Just as the African American context, the beginning with the oral tradition has been at the heart of American music, it can provide like other cultural traditions a limitless material for constructing the narratives of black space within the spheres of memorialization, design and architecture. The impact of slavery on American society is often considered but its consequential impact on society as a whole does not receive the same type of attention as it should.Rodney Leon:

This lack of acknowledgement is a blatant disavow of the significant role that Americans of African descent have had in building the United States and in the Western hemisphere. My perspective is formed by my context as an African American of Haitian descent. Haiti was the first independent black Republic in the Western hemisphere and was freed and founded by formerly enslaved people who banded together in armies to defeat the British, the French and Spanish forces.Rodney Leon:

The slide that I'm showing you now, the Citadelle Laferrière was conceived and constructed after Haitian independence in 1804 and was the largest in a series of fortifications built by Haitians to defend their country from attacks by French and other European forces. It is still one of the largest fortifications in the Western hemisphere located at the top of a mountain in Northern Haiti, the Citadelle allowed 19th century Haitians of vantage point over the adjoining valleys and the Atlantic ocean.Rodney Leon:

The French invasion that the Citadelle was built to deter, never came, but the enemies of freedom and Liberty found other ways to punish the nation through repayment plans, trade embargoes and political interference. The lingering results of this long-term interventions have made Haiti one of the poorest countries in the world today, however, I would say one of the richest culturally.Rodney Leon:

The Citadelle remains a beacon and a significant cultural icon, a work of architecture that monumentalizes the ongoing project of liberation, as it simultaneously memorializes those who suffered and those who continue to suffer in the aftermath of slavery. My identity as an African American of Haitian descent connects me also to the context of the Citadelle Laferrière and in turn, the Citadelle brings us to the greater context of African American and American history consider this narrative of liberation.Rodney Leon:

The Haitian, that army of defeat of France precipitated the sale of the Louisiana territories to the United States. The United States was able to acquire 828,000 square miles of land West of the Mississippi river in a single purchase. Without the abolition of slavery in Haiti and without the successful war for Haitian independence, France would not have sold the Louisiana territories to the United States, which therefore would likely not resemble the nation that we all know as it exists today.Rodney Leon:

Without the secrets of events that instantly doubled the country's area, with the project of Western expansion have occurred at all. Also consider this brief narrative, in 1790 Jean-Baptiste DuSable, a Haitian Explorer, became the first permanent resident and founder of what is today, the city of Chicago. The city was founded by a black man from Haiti and he is honored by the monument commemorating this contribution, and this is less than 100 years, well actually quite not that many years after Haitian independence.Rodney Leon:

I comment upon the sometimes under-emphasized and often concealed histories, because the process of revealing informs my work by helping to provide more inclusive historical narratives to society's knowledge and experiences. In my academic and professional practice, I strive to understand culture and history as a basis of modern identity and seek to create formal architectural language reflecting this condition.Rodney Leon:

Most of us fail to comprehend the degrees to which our own lives have been influenced, and are connected to the legacy of people of African descent as well as a confluence of others. My identity is constructed from a combination of American, Haitian and African components, as well as European and perhaps native components. The journey I've taken in my adult life through my work reflects the process of attempting to understand how these multiple cultural elements form the basis of my own identity and in doing so, acknowledge the role that the transatlantic slave trade played as a powerful catalyst in its evolution.Rodney Leon:

While a student in architecture school I began to be interested in the possibility of establishing contemporary expressions of African culture through architecture. Soon after graduation, I took the opportunity to spend a few months to live and work in the Ivory Coast in West Africa. This experience helped me to more specifically synthesize my contemporary ideas relating to African inspired cultural and spiritual form. It was upon my return to the United States that I was able to apply some of these concepts as a designer for the African Burial Ground Memorial, and later for the Ark of Return.Rodney Leon:

One of the biggest challenges in developing a design for memorial project is to understand and to interpret program requirements established by multiple stakeholders. The functional requirements are often complex and contradictory, I feel as a designer though it is important to expand upon the existing program and establish a set of objectives, expectations and criteria that the project must meet in order to be considered successful prior to even putting a pencil to paper.Rodney Leon:

Some of these primary objectives are as follows, education, and I would state this almost as a kind of like a manifesto, a memorial most first communicate and educate. I maintain that architecture of memorialization must communicate and educate as a timeless teacher. The Memorial communicates history for generations to come, as one engages both visually and experientially, one must become enlightened to the sacred cultural and historical significance of an event or an individual precipitating the memorial's creation through the medium of space, form, language, symbol and ritual.Rodney Leon:

The memorial must be a medium of communication and education for all people of all ages, classes, genders, religions, nationalities and ethnicities. A memorial must also have a significant and powerful urban presence, a memorial must be seen at a distance and standout to establish itself visually and formally within the fabric of its environment. The memorial must be able to accommodate large groups of people, as well as intimate scale spaces for personal reflection and contemplation in order to function at the scale of the individual and function at the scale of the city.Rodney Leon:

We also believe that our memorial's design must be what we call culturally contextual. By that term, I mean the language form and function and ritual behind the elements constituting the memorial should be inspired and/or derived from some cultural or historic precedent. Historical precedent for our forms are often influenced by both traditional and monumental African architectural typology. The desire is not to reinvent the past forms but to learn from them so that they may be synthesized into a unique contemporary architectural expression.Rodney Leon:

A memorial must also utilize spiritually and culturally recognizable iconography. A memorial must be seen and engage, and engage the language of the icon as an image that identifies the site and the memorial universally in people's minds and establishes the memorial as a monument that carries and creates meaning.Rodney Leon:

A memorial site must be designed as a sacred site, and a memorial as a sacred object within that site. The memorial site must be designed as a sacred space with the memorial itself within that space, a sacred object that carries memory and culture. Memory and culture are inherently loaded with issues related to death, loss, triumph and tragedy that can be both sensitive to the individual in different ways.Rodney Leon:

These memories as well as people that created them, sustained them, must be celebrated. The site must be a place of pilgrimage and the monument, a place of reflection. Memorial exists typically within a public space and must be designed as a place of collective acknowledgement and reflection. The monument must speak to all people into our shared experiences.Rodney Leon:

Its beauty, meaning and power must be expressed in a manner that transcends difference and brings people together, it must be universal, it must be seen as an opportunity to communicate historical and spiritual values to people from all over the world through a common language.Rodney Leon:

A memorial must also be interactive and participatory, the monuments must offer visitors active participation in a ritual, a physical interaction. The visitor's senses must be engaged to the use of multiple mediums of expression and encourage people to interact physically within the space in a meaningful way.Rodney Leon:

We want to invert the classical idea of the monument as being something to stand away from and look up at, or look at us. Through the element of ritual, visitors can become active participants through verbal and physical action and movement. One must be induced to see, touch and even listen to the memorial. The memorial must not be static as an object but be a living and breathing space.Rodney Leon:

For the African Burial Ground Memorial, it was in May of 1991 that the United States General Services Administration was preparing to build a federal office tower at Broadway between Duane and Reade Street, that the first human remains from the 18th century African Burial Ground were accidentally uncovered. Construction was subsequently halted, and the resulting archeological excavation unearthed more than 400 skeletal remains.Rodney Leon:

Those remains were of men, women, and children along with hundreds of burial artifacts. Archeological research determined that approximately 60% of the remains were of adults and 40% were of children. Life expectancy of the adults was on average, not beyond their mid-30's. So this is an image of one of the remains that was uncovered by the archeologists while they were excavating the Burial Ground site.Rodney Leon:

The discovery of the African Burial Ground called into question conventional history that slavery in the United States was primarily a Southern institution. The presence of the Burial Ground brings to light the fact that New York City was not only a major slave port in the 1700s, but had the second largest enslaved population in colonial America during the 18th century.Rodney Leon:

During that time, the African descendants comprise between 14 and 21% or more of the city's population. More importantly, the Burial Grounds discovery again, highlighted specifically the role that enslaved laborers, free farmers and freed individuals of African descent played in the building and prosperity of New York City.Rodney Leon:

The African Burial Ground is widely considered to be one of America's most significant archeological finds of the 20th century. And in 1983, the burial ground was designated a national historic landmark. This is a fragment of a map that can be found in the Library of Congress, called the Van Berson or the Marshaks map, which is a very weird name, but what it's showing is if you can kind of make this out, it says Negroes Burial Ground. This jagged line is a fence line that runs East and West, and it's essentially at the location of what would now be considered Duane Street. And this edge here would be considered like Broadway, this area where the commons is essentially where today's city hall exists.Rodney Leon:

And at the time, this line, just north of city hall, around Chamber Street, was the Northern most boundary of New York City. So at that time, New York City pretty much stopped right behind city hall at Chamber Street. So this fence line, which is part of the Van Berson plot everything north of that fence line was essentially a sloping swampy kind of like wilderness. This indicates a fresh pond that was there and just to the West of that pond was what they called Potter's Hill and when the Dutch lost New York to the British, the British no longer allowed people of African descent to bear they're dead within the boundaries of the city.Rodney Leon:

So just North of the boundary essentially became the place where the Negros Burial Ground, the African Burial Ground as we know what today allowed that to spring up. Over time that New York expanded northward, the swamp and the pond were drained, the hill was raised, this area was filled over and covered over and then New York essentially expanded northward from there.Rodney Leon:

We commemorated the African Burial Ground with an Ancestral Libation Chamber through seven elements. The Ancestral Chamber serve to physically, spiritually, and ritualistically define the location where the historic reinterment of remains and artifacts of 419 Africans has taken place. It also serves to acknowledge the site as a sacred place where estimated 15 to 20,000 African descendants are currently buried. There are seven elements that comprise the African Burial Ground design. The first is the Wall of Remembrance, and on the North wall as you walk along that area of Duane Street, you will see inscribed the phrases "for all those who were lost, for all those who are stolen, for all those who are left behind and for all those who are not forgotten."Rodney Leon:

This is an image of that Wall of Remembrance. And to the left of that is an image of the Adinkra symbol from the West African people, which is called the Sankofa symbol. That Sankofa symbol was found on one of the archeological remains on one of the bodies that was uncovered, so they believe that they came, that person or some of the people came from that part of West Africa where the Adinkra originated from. We would know that area right now to be gone on the Ivory Coast essentially.Rodney Leon:

So that meaning behind that symbol is to look back to the past in order to understand and move forward into the future. So it became a kind of like a symbol which was reflective of the project as a whole in terms of like its meaning and significance. The second element is the Ancestral Reinterment Zone. In October of 2003, seven large sarcophagi guy would inboxes containing the remains of zoomed African descendants were ceremonially reinterred on this part of the site. The zone of reinterment is marked by seven large burial mounds, identifying the location of the descendants are originally uncovered at the site.Rodney Leon:

You can see these large mounds here where the reinterment of the 419 archeological remains that were uncovered were reinterred, and those mounds are located on the east-west axis on the site. If you were to look at a plan of the exhumed grave sites at the time, all of the bodies were laid on an East West or orthogonal condition where the heads to the West and the feet pointing to the East.Rodney Leon:

So we created these mounds in the same orientation along that 18th century orientation in kind of like a skew to the 20th century street grid as a homage to how the bodies were originally discovered. The next element is the Memorial Wall.Rodney Leon:

The Memorial Wall serves to visually clarify the scale of the actual Burial Ground versus the scale of the Memorial site. Because the original boundaries of the African Burial Ground extend significantly beyond the boundaries of the memorial site itself. Over time, the original boundaries have been lost and in order to communicate that fact, we inscribed a map on the Southern wall of the ancestral chamber.Rodney Leon:

The map on this wall serves to clarify the extent of the Burial Ground's actual size through lower Manhattan. So, in this image you can see there's a little -- You can see there's a little rectangle that's the corner where the memorial site is located. That's about a quarter acre. And you can see the 20th century grid, this is Broadway. City hall is right about here. This is fully square where the major courthouses are.Rodney Leon:

This sandblasted area shows you the actual scale of the Burial Ground about 20 feet below ground at extends from Broadway all the way to Foley Square. So it's about 16 times the size of what you see when you go to this site. The Ancestral Chamber is this form that we use to transition between the realm of the living and the realm of the dead. The Ancestral Chamber is a spiritual form that rises out of the ground about 20 feet above street level. This height represents the distance down when we'd have to excavate in order to reach the level of the original Burial Ground.Rodney Leon:

The form of the Ancestral Chamber is a synthesis of both traditional and monumental African archetypes representing a soaring African spirit, embracing and comforting all those who enter. Their collective energy and spirit thrust upwards out of the ground towards heaven, reclaiming their honor and place in history. These ancestral Africans were taken from their Homeland through a door of no return.Rodney Leon:

These are some sketches of some of the concepts of the Ancestral Chamber. The sketch up right now shows that the chamber essentially is transitioning between upper and a lower level and that you pass through the chamber in order to go from a more public space, a more secular space, and then you go down through it into a more private space.Rodney Leon:

The Ancestor Chamber is a vessel that serves as a take us back to an original place where we all began. These ancestral Africans were taken from their home land through the door of no return. When enters the Ancestral Chamber through a door of return, it provides a sacred space for individual contemplation, reflection, meditation, prayer and healing. This is an image of myself at a place called Goree Island in Senegal.Rodney Leon:

In the door, there's the door of no return, which is a door where people were taken from slave ships, never to be seen again. So we created in the chamber a concept of a door of return as an inflection point and a place where people can then can understand and acknowledge that part of the history but actually create a kind of like an inversion in the possibility of return psychologically and spiritually going back to a place where we all began. The idea is about not just commemoration of the tragedy but about the possibilities for hope and healing.Rodney Leon:

So here are some images of the actual door of return. The symbol above the door is another Adinkra symbol. That's Adinkra symbol for hope. The idea of passing through that chamber is supposed to also acknowledge the idea of the middle passage, this space is a kind of a dark space, it's a space but also has the possibility for light and for transition to occur and passage to occur.Rodney Leon:

So there's a triangular Oculus and there's a triangular entrance that points you to the court when you pass through it. So the idea is going from a kind of darkness into light as a transition space from the secular to the sacred. The Circle of the Diaspora constitutes a series of signs, symbols, and images engraved around a perimeter wall and circling a libation court. These symbols come from different areas and cultures throughout the world, especially Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.Rodney Leon:

Symbolic meaning is described below the images are inscribed on the wall. As one moves around or circumambulates around the perimeter of the court and spirals down the processional ramp, these symbols present themselves as a reminder of the complexity and diversity of African cultures manifestation in the Western hemisphere. The spiral processional ramp descends four feet down below street level, thereby bringing visitors physically and spiritually closer to the ancestors original interment level. The ramp and stairs serves as bridges between living in spiritual realms. They symbolize the process of transcendence from spiritual, physical to spiritual and passage from profane to sacred.Rodney Leon:

The ancestral Libation Court is situated on access with the Ancestral Chamber. It provides a physical and psychological separation from the public activity surrounding the environment. Inscribed in the surface of the Libation Court is a map suggestive of the migration of culture from Africa to North America, South America, Central America, and the Caribbean. The Libation Court is a communal gathering space where small to medium scale public cultural ceremonies can occur.Rodney Leon:

This is a spiritual space where re-consecration of the African Burial Ground site will continually take place during libation and other ceremonial rituals. The ritual level libation is an act which will serve as an offering and an acknowledgement linking past, present and future generations in the spirit of Sankofa. This image is an interesting image for me because I've been to the site on numerous occasions and have seen different groups of people come to the site and pay homage to their ancestors to different spiritual traditions. In this particular instance, it's a group of women who have come here as part of a Shinto Shrine and have intuitively understand it how to embrace this space and occupy this space and utilize the space according to their own spiritual traditions.Rodney Leon:

And I believe that this is the kind of thing, not just for like the idea of universalism but the idea that these spaces, and these places and these monuments need people's connections and interactions in rituals and cultural ceremonies for them to be living and breathing spaces and active spaces.Rodney Leon:

This slide shows an intersection, I think of, I find it interesting of the different elements together. There's a young woman who was looking at some of the symbols that are engraved in the circle of the Aspera at the bottom of the spiral processional ramp. You can see the intersection of the court, the chamber, the memorial wall, and the Wall of Remembrance and in the distance, the mounds and the trees behind the Grover reinterment. I'll close with the Ark of Return, permanent memorial to the United Nations to honor the victims of slavery in this Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.Rodney Leon:

Acknowledging the tragedy, considering the legacy, lest we forget. Our three distinct phrases individually and collectively that were established as a theme for the competition and formed the inspiration for the design for our memorial in honor of the victims of slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade entitled the Ark of Return. The Ark of Return is organized around a three part theme. The primary formal element used is the triangle, which references the triangular slave trade. The triangles come together collectively to form a shape, reminiscent of a vessel or a ship.Rodney Leon:

This is meant to acknowledge the fact that it was physical ships that transported the millions of African people to the Western hemisphere during the middle passage. These are sketches of some of those concepts of the ship. So through the Ark of Return we would propose a spiritual vessel and a sacred space that psychologically and spiritually is meant to transport humanity back to a place where acknowledgement, reflection, and healing can take place.Rodney Leon:

Through the memorial's three-part organization, visitors are meant to pass through the Ark of Return to experience these three elements located within the interior of this space. These elements encouraged people to acknowledge the tragedy, consider the legacy lest we forget, and upon one's arrival in the plaza just to the North of the general assembly building, one will be greeted by an image of a glowing white marble form prominently placed on central axis with the plaza.Rodney Leon:

A triangular window at the side of the monument draws one towards it. On axis with the opening prominently featured on the interior wall is the outline of the African continent. As one draws near and looks through, we see that the relief of Africa is part of the first element, a three-dimensional map inscribed on the interior surface of the memorial. This map graphically depicts the global scale complexity and impact of the triangular slave trade in acknowledgement of the tragedy. One thing you can't see very well in the images that it's meant to be interactive that you can touch it.Rodney Leon:

There's 66 locations that we were able to research where people were physically taken away to different parts of the world that are inscribed on that map. The African people transport it under extreme conditions during the middle passage, visitors are provided the opportunity to sincerely consider that legacy upon slavery's, and slavery's impact upon those people's lives.Rodney Leon:

The second element is a Trinity form and that Trinity form, you can see like the image of a body with an outstretched hand that kind of draws you into the space. This is an image of the entry point into that space, and of the Trinity form itself lying within a triangular niche.Rodney Leon:

We call it the Trinity form because it is meant to be in honor of the people, the men, women and children that died during the triangular slave trade. So this Trinity form itself is almost like the spirit of those people that died being brought back to the African continent. You can see the outstretched hand, it's constructed as Zimbabwe, black granite, and the robe is handcrafted from a white marble from Italy and Carrara.Rodney Leon:

The third element is a triangular reflecting pool or font, which introduces water in a meditative, ritualistic, and spiritual manner. Visitors are invited to pour libations or say a prayer in the memory of the millions of souls that were lost, lest we forget this monumental and historic tragedy. In front of that, as you pass through, it's kind of hard to see here but the names of, right about here on the lower area, the names of the people and the locations I should say, of the people where the people were taken from is inscribed in the front.Rodney Leon:

In closing, I've come to the realization and believe that the process of memorialization is in itself for me, a sacred act to approach it as anything less becomes essentially a spiritual transgression. We are all entrusted with the responsibility to interpret the contribution to history of our ancestors for future generations, thereby acknowledging their humanity in a way that was not possible when they were alive.Rodney Leon:

This task has become even more difficult when we do not specifically know the details about the names or the lives of the people that we memorialize. For that reason, I believe it's an appropriate response requires the incorporation of multiple mediums of communication into the design in order to achieve our objectives. This allows us to see memorial design as being constituted of more than just purely physical form and space but also about ritual memory and what we all hold most sacred. Thank you.Denise Herd:

Thank you so much Rodney, that was marvelous. Now we're going to invite our faculty up to have a very brief... Rodney, do you want to stay up? A very brief Q&A with the faculty Professor Stovall, Raiford and Kroiz. Would you like to come up and just have a seat? Yes. Come on up.Denise Herd:

Yup, you may seat.Leigh Raiford:

Well, thank you so much. It's really a gift and an honor to be able to kind of walk through both of those memorials with you, also as a New Yorker. So I really appreciate that. So we have an L&S 25, we generally have two questions that we begin and end every public speaker event with and I'm hoping that you can take those on for us.Leigh Raiford:

I think the first you've answered quite beautifully, which is for us as is how do you define public art and why does it continue to matter? And then secondly, our students will be designing their own proposals for or their own public monuments works of public art for this campus as their final project? And so we ask our guests to consider what kinds of public art they would like to see.Rodney Leon:

Okay, great. Everybody can hear me? I think that just even visiting this morning around Berkeley's campus and being from the East Coast and understanding the context of free speech and Berkeley's plays in the history of free speech and liberation and struggle politically, both in the past historically but also to a large extent, I believe currently in the future that there's so much of a reservoir of history and cultural here that can be mined for memorialization, interpretation, communication and manifesting itself on this campus.Rodney Leon:

I think that there's no lack of resources available for me that history and that culture is a resource and a materiality to work with. So I think that it's almost like a Booker T. Washington says, "Cast your bucket down where you are." You can do honestly a lot worse than Berkeley as a resource for memorialization from the struggles of free speech to the women's strike struggles of struggles of migrants. We saw so many different, even in the short time that I was here.Rodney Leon:

Places and spaces that I think deserved even more reflection, opportunities for reflection that essentially are like really an extension of the history of this place really. And in a lot of ways revealing that even in a more powerful way I think, it sounds like an exciting opportunity for a studio or for a class.Lauren Kroiz:

Thank you. Do you have a question? I don't want to... I can ask one too. I'll take it, I'll take it first. I am particularly struck, thank you so much for your talk. And I'm particularly struck, I hadn't seen the images so big before and I haven't encountered any of them in real life yet, although I'm hopeful that I will. I was so struck by just how beautiful they are, and when you were talking especially at the end about the different kinds of stone that you're using and the way that they're crafted. It helped me think more about the kind of spirituality and sacredness that you offer.Lauren Kroiz:

And I was wondering if you could think more with us about the role that beauty plays in your work, especially thinking through histories that are so hard and so difficult.Rodney Leon:

Yeah. Thank you. That's a very interesting comment and observation. I think that you don't necessarily equate like a lot of these tragic histories with like something beautiful, but part of honestly what it is that I'm looking for when we're going through this process is for us to acknowledge the tragedy, but at the same time find an opportunity to draw people in for an opportunity to learn and to heal. It's often very difficult to find that balance, and that's why I think the first contextual element of education is really critical because utilizing the place like let's say the Burial Ground or the Ark as a mechanism for developing a narrative for teaching about our colonial and the legacy of slavery, I think is one of the most important things I think I wanted to achieve.Rodney Leon:

And for many teachers, especially as a primary school teachers and for people who are young students of color and also people who aren't, there was an aspect of like fear and shame that we have to be able to overcome. And I think that if you create a place or a space that has a focus on healing and a place of beauty, it allows there to become more of an opportunity for us to be able to collectively learn. And to move beyond the tragedy and the sorrow and the hate and the anger and the fear and then get to a point where we can get to the point of healing. So that's where I think beauty plays that role to kind of like draw people in.Denise Herd:

I just wanted to ask a question that's kind of related. I was impressed by not only the beauty but the dignity of the memorials and of the figure, especially on the Ark of Return because some of the other memorials around slavery just do not express that kind of dignity and respect to the person.Rodney Leon:

Yeah. I think that also there's these kind of complex and contradictory needs that have to be met, when you have a part of the first question I also had to do with like public space. When you're dealing with a public space that has to deal with not just these kinds of issues, but let's say this is a cemetery, right? You have to deal with the fact that it's a sacred place.Rodney Leon:

How do you make a space public and accessible at the same time? Have people respect it in a particular way? So you have to create, I think, a balance of respect through what kind of like exuding a kind of like a sense of sacredness. And you also need to provide an opportunity for people to be able to reflect individually but also for groups of people to be able to teach or congregate for spiritual or educational purposes.Rodney Leon:

And then there are also larger gathering that need to take place also, let's say annual ceremonies. So you might have like literally like thousands of people congregating around a site like that, in October they do these kind of like annual reinterment ceremony events. So, there's this kind of like tricky balance for contemporary spaces like this in order to be able to work and operate on these kind of multiple levels simultaneously.Rodney Leon:

And for me, you can achieve that through multiple. That's why you need multiple elements dealing with multiple issues. It's not necessarily kind of like a singular kind of issue. Like a classical idea of a monument, if you take like a Confederate monument, it's a very kind of like a thing coming from like a kind of classical history where you have an individual on a pedestal, you're looking up at them, you're meant to be in awe of them. You're meant to look at them but not get too close now, don't touch this person because this person is way above who we are. That's the experience.Rodney Leon:

And it's also kind of like, if you think about it, if you think about a statue, there's only really kind of like a front, and when you look at the back it's sort of like you're not really meant to interact with the back or even kind of like the side. It's meant to be this kind of like a psychological relationship that's established. Like a person is here and then you're down there, as opposed to what I call a kind of like a more fluid interactive kind of relationship, which is we're both sort of like they were a person so we can maybe connect at a kind of like a personal level.Rodney Leon:

And maybe it's not about this like the physical manifestation of the form of the person, but really the spirit of what that person represents. So maybe there is a kind of like a physical presence there or maybe it's more of an abstraction about what they represent. So that when you're experiencing this space, where you're experiencing this space in a much more interactive way where your experience is more of a kind of a physical connection with the memorial or with this space, with the person, with the object. And that's why I believe you need to have that kind of like flexibility and multiplicity.Rodney Leon:

And you have to understand that you're dealing with people of all ages and different cultures in public spaces. So you're not just dealing with individuals groups in let's say large gatherings, you're dealing with like children, people with disabilities both physically and visually. So people who have visual impairments can touch and still have an interaction. People with impairments that they can have like say you can hear like the waterfall if you can't see.Rodney Leon:

And I think that, that multiplicity makes it much more accessible. And to me that's much more about what a contemporary public space should be like. It needs to be as accessible and as complex and provide as much opportunity as possible for people to interact with it on different levels and to take from that experience something that they can hold onto and hopefully that way becomes more transformative.Rodney Leon:

And it also meets people in a communicative way at their level in through a mechanisms that they can engage in or that they find to be much more I think therapeutic when they come to a space. So you can see like some people like to sit on the bench by the memorial wall, which is quiet. Some people like to be there on the lower level of the court, some people like to be within the chamber, some people would like to be more towards the landscaping. So I think that, that talks about multiplicity and complexity versus heterogeneity and singularity, right? It talks about inclusivity as opposed to these kinds of barriers, right? Walls and these other kinds of things that divide us. So that's part of like the concept.Tyler Stovall:

Again, thank you. I wanted to ask about the whole way in which you approached the idea of return or non-return. You have these parallel sides, one of which is called the door of no return, one of which is called the Ark of Return. What did it mean to you to deal with this concept of return in this case? And if you talk about return... if you talk about return, return to what and who's returning?Rodney Leon:

That's a good question. In the door of return that we implemented in the African Burial Ground and in the Ark of Return, which was actually the space itself, we're still talking about an acknowledgement that the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade really had this kind of significant, I say impact on people in a transcendent, I would say even kind of like the time that it occurred. Like we're still in a lot of ways dealing with the residual impact of slavery in the 21st century. And it goes back to this idea of like healing.Rodney Leon:

In some cases it could be thought of as a kind of an encouraging, a kind of physical return. But it's really more of about an idea of a process of like learning what was perhaps lost or concealed again from that Sankofa symbol to go back to the past or history to understand better so that you can move forward into the future. So that idea of the return is really an idea that is in some ways kind of like therapeutic or therapy if you could use that word. And it's an idea of the process of learning, understanding, healing, moving forward and being hopefully made whole again.Rodney Leon:

So when I went to Goree Island in Senegal in that image where I was standing at the door of return, what I did was, this is what people don't usually do, what people usually do as they go through this place, the house of slaves and then this door of no return, they kind of go through to people tell the story that they experienced. They felt like they would be being taken away when they went through that experience. When the people that were enslaved and kept there, it went through that experience. They almost kind of feel that sadness, that energy.Rodney Leon:

When I went there, I purposefully went around from the water side, from the ocean side where the rocks were and kind of climbed through and came through the other way. Sort of like, for me, it was like the idea is like, "Okay, ancestrally someone was taken away, but we can come back," and you know what I mean? So I think that for me, that's how I approached this idea also of the return, that it can be in some instances a physical return, but we don't necessarily know where we came from. You can't pinpoint it exactly, but I think it's more kind of like an emotional, psychological opportunity to transform and heal through that experience.Rodney Leon:

So both through, I wanted to kind of like replicate that opportunity outside for those who aren't able to actually go back and say to Africa or wherever, they might've come from ancestrally. I wanted to recreate that opportunity in New York at the Burial Ground site and also at the site for the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade at the plaza, at the United Nations as a kind of like an opportunity for people to experience that transition, that passage and the opportunity for the healing to take place and that's what really the return is about.Leigh Raiford:

We have time for two questions and we'll take them both and then we'll go ahead and answer them. So we have, okay, we'll do three questions there and then these two questions here. Just wait for the microphone.Clarissa:

Oh, thank you. My name is Clarissa. I'll be 90 years old in August. And I remember when I was a child growing up my great grandmother had come from Guinea as an enslaved person, and along with her cousins she had a chance to actually grow past in a respect to tragedy of being enslaved, but she always wanted to return home.Clarissa:

She lived to be 102 but she never had the opportunity to return home, but she was a very gentle and very soft person. And we as children loved to gather around her and just to hear her stories. She's buried now in a small town called Bellville, Texas where we grew up as children, but it was a wonderful experience just to know that she lived and she had this horrific experience being separated from her parents as children to make that journey across the Atlantic Ocean, to be enslaved, to be sold to others, to be abused sexually, to have children that were part European because of the abuse. And yet she survived that tragedy and lived as a complete person for 102 years.Rodney Leon:

Thank you for sharing that. That's beautiful.Rashid:

Hi, my name is Rashid and I'm a fan of Clarissa here since we were at Laney College. And I have two questions. So first, a few years ago, I was able to go to New Orleans and I saw while I was still there the Robert E. Lee statue that was there, and I don't know if this is true or accurate but someone said that the monument faced North because you never turn your back on the Yankee and there was some idea of this resistance to the North.Rashid:

And so again, I didn't see it written anywhere. And so my first question is about any hidden meetings in public art and what's maybe the value and if you've done any of that that you could share in company here. Maybe not everybody, maybe just me and Professor Raiford later. But just that hidden meaning and statues. And then the second is just if you had any thoughts about the removal of these statues and monuments that we're seeing throughout the country.Leigh Raiford:

And let's just take that last question. Let's take that last question right there and then you can answer all of them together.Rodney Leon:

Okay.Leigh Raiford:

Thanks.Tony P.:

My name is Tony Platt. Thank you very much for your presentation, I think we have a lot to learn from you here in California and here at the university. I don't know of another memorial other than the African Burial Memorial in New York that does the combination of things that you do there. It respects science, the archeologists were brought in to look at the human remains, it respects education. You didn't show a slide here, the educational part, but it's a very important part of the memorial. You have ceremonies, you have rituals, you have participation.Tony P.:

I don't know of any other place, any other memorial in the United States that does that. You'll find places like that, of course, in Germany and other countries, but not here in the United States. Here in California, our slavery has a lot to do with the history of native people in California. The genocide that took place in the 19th century, the enslavement that took place after the genocide for the survivors of genocide. And then on top of that, the looting and stealing of human remains and funerary objects from graves that took place all over California.Tony P.:

And here in this university, this university provided the leadership in the looting of graves taking some originally 10,000 human remains that are kept on campus or about 9,000 here. I don't know if today when you got your tour of the campus that this was pointed out to you, the place where those remains are. But this is sort of the longstanding, well-known, dirty secret of the university. And it's something that I think this university has to come to terms with and has to learn from the kind of example that you've set.Tony P.:

And then that was an observation, and just a quick question because from what I understand in what happened in New York is that there was tremendous political activism around the site, and that this is a very expensive, valuable piece of property that this memorial is on. And there was a lot of interest in developing it for other reasons.Tony P.:

So the question is, to what extent do you think that long history of political activism around making the site into what it is today and getting you to be a part of it, how much do you think that was responsible for the outcome and the results that we have. And is that a model then for those of us here in California trying to get this university to respect its tragic past?Leigh Raiford:

Thank you.Rodney Leon:

Thank you for those questions. I guess I'll start with Rashid. I mean in regards to symbolism I guess you were asking about, a lot of what it is that what I do is really kind of symbolic. It's laden with like a lot of symbolism and meaning and I think that memorials, the occupy kind of like a space between let's say traditional art and sculpture and architecture. So their role is not to give you a kind of like a literal interpretation.Rodney Leon:

And at the same time it's not also not meant to be completely an abstraction. There's information there and the question is like, and there was an important part of history that somehow they are within there, that space itself and within the objects themselves. The question is like, how does one begin to allow people to feel that importance and engage the experience so that they can take with them the meaning and the power behind what's being memorialized.Rodney Leon:

And we tried to do it in a way that's more spatial as opposed to as formal, even though the work is also very formal. But I think when you're doing these kinds of things that are formal without space and people don't have the same level of kind of like experience. And you see like these different elements, there's always sort of like a kind of like an underlying meaning through it.Rodney Leon:

So when we were presenting today, we were trying to give you a sense of like what some of the meaning behind a lot of these forms are, because most people when they come to the site, let's say, like the Burial Ground, they'll notice like the reinterment zone and the mounds, so they'll intuitively maybe lay wreaths or flowers or other objects they are on those mounds because they have a symbolic relationship to burial mounds at cemeteries or other types of larger burial mounds.Rodney Leon:

And there was that slide of the Shinto Shrine participants who came to the Libation Court and they didn't provide libations but it is something which is kind of very interesting, which I guess Asian cultures as well as African culture and other cultures do, which is place these kind of like food and offerings in the center of the court. And then essentially go to four corners and make their ritualistic homage to their ancestral spirits.Rodney Leon:

So these are things that in a lot of ways transcend, let's say this like even libation itself transcends, let's say the experience of African people happens in Europe, Asia, and other places. So we were trying to create symbolism that ties back to the meaning of the site specifically but also kind of like I think universal symbolisms. And when you go to the site, there's no place that's really kind of explaining all this kind of stuff to you.Rodney Leon:

Like you don't know like why they're seven elements or why they were seven mounds, but you know somehow that there's something that lies beneath this that's significant. So yes, symbolism plays a role and you're in this presentation that they were able to kind of explain some of that symbolism. But there's also other things that we can kind of, we have time we can kind of talk about also in terms of like the cosmology behind how the spaces were conceived in three-dimensionalize and how that relates to a Congolese cosmology and also how that translates to the kind of like more diasporan spiritual beliefs practices. That's three-dimensionalize. So that there's more to it than that.Rodney Leon: