by Derrick Duren

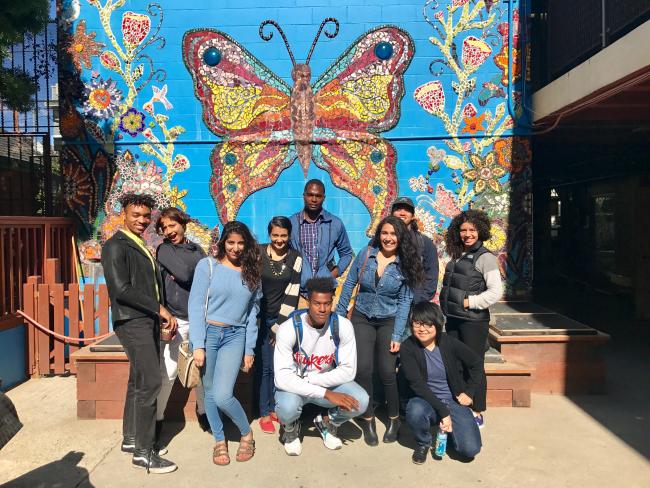

In an effort to better understand different strategies for attaining communal preservation, the 2017 cohort of summer fellows visited several organizations currently working to combat gentrification practices in the San Francisco Mission District. Once occupied primarily by low-income Black and Latino populations, the Mission District is now a cosmopolitan social space for many of San Francisco’s wealthier residents. The fellows examined community preservation strategies from three perspectives: art as resistance at the The Clarion Alley Mural Project, the business of restorative economics at La Cocina Community Kitchen, and radically-inclusive social services at the Dolores Street Community Services Shelter.At the Clarion Alley Mural Project, the fellows sought to explore how art can be used as a form of resistance in a modern context. Opened in 1992, the public art exhibition located in a block-long alley has hosted over 700 murals for the purpose of building an educated and equitable community in the Mission District. Current exhibitions include powerful images of local victims of police brutality, critics of capitalism, glorifications of Black trans women, and other justice-oriented works. With more than 200,000 annual visitors, this free tourist attraction uses socially conscious artwork to express utterances of resistance to an international audience.

“This space began as a meeting place for artists and activists here in the city,” said the project’s director Christopher Statton. “Neighbors would meet here to create art and talk social strategy. Over time, people collaboratively repaired more and more fencing along the alley, making room for more art.”

Next, at La Cocina Community Kitchen, the fellows sought to understand how a business that employs community members and prepares them to start their own businesses could be a tool for implementing structural change in the Mission District. The non-profit organization works to support small business owners from at-risk communities in attaining the certifications and knowledge necessary to maintain a successful Bay Area restaurant.

La Cocina Community Kitchen has graduated dozens of popular Bay Area restaurants, many of which are expanding outside of the region. The community kitchen offers members a state of the art space for commercial culinary practice that enables members to sell quality meals to a network of popular Bay Area distributors.

As the economy of the San Francisco’s Mission District is centered around culinary businesses, this community kitchen is a hot spot for low-income Mission residents looking to become self-sufficient entrepreneurs.

“We have made several business successes in the San Francisco market by changing the way they approach selling food,” said Culinary Manager Blake Kutner.

Last, at the Dolores Street Community Shelter, the fellows toured an organization pioneering radically-inclusive social services for the homeless. The Dolores Street Services Center is a crucial resource for the Black and Latino community members in the Mission District who are homeless or living with HIV/AIDs. The center runs churches and residential properties in the neighborhood that are some of the safest spaces for people at risk of being institutionalized. In 2015, the shelter opened 24 beds designated for Queer and Trans* people, making it the first LGBTQ+ shelter in the country. Today, the organization provides more than 100 safe bed spaces for men, women, and gender nonconforming people displaced due to the rising cost of living in the Mission District. The fellows unpacked the strengths and challenges of this organization’s unique structure as an exemplary social services entity.

Through these on-site research visits, the fellows observed that resisting the negative impacts of gentrification is a layered issue that requires both accessible and intersectional approaches to community empowerment, and that these approaches must prioritize those who are most at-risk in a given community to be impactful.

Arts organizations are faced with the challenge of evading oppressive institutional funding, attracting audiences to socially-conscious topics, and thereby shifting power dynamics in favor of those at risk of indefinite displacement. Businesses interested in social equity must avoid perpetuating or validating gentrifying practices, create employment and investment opportunities within resource-deficient communities, design pathways for community development that can be self-sufficient, and show other businesses that being successful doesn’t have to be exploitative of any population. In addition, social service organizations must respond intentionally to the ever evolving needs of marginalized communities and assist holistically the multivariable livelihood of those most impacted by social inequalities.

Derrick Duren, a member of the 2017 summer fellow cohort who worked with the Richmond Partnerships program, spoke with the summer fellows about their experience and perspectives on the impacts of gentrification.

After seeing Clarion Alley and learning about its rich history, how has your perspective on art as a form of resistance changed?

EJ Toppin (Community Partnerships): Sometimes it's difficult to put words to the emotional damage forms of oppression cause, or to articulate the injustices one experiences or witnesses. To see artwork speak that, to encapsulate exactly those thoughts and feelings, is empowering. I only worry that the point of the alley's art is being missed and going over the heads of the people who need most to understand why it's there.

What priorities do you think local officials in San Francisco should consider when creating policies that deal with property ownership in The Mission District?

Tanv Rajgaria (Leap Forward Project): Preservation of: local architecture, culture, lived histories, help for struggling communities that have been here or are becoming increasingly a part of the area. Rent control is a difficult game to play in America, but there should be a way to bend developers' ears into allotment of some number of lower-rent units, and supervision of where displaced people go (here being sadly realistic about the life and times we live in).

What are your thoughts on the supportive business model for new business owners, such as the one adopted by La Cocina, as both a consequence and benefactor of gentrifying populations?

Rhonda Itaoui (Global Justice Program): The business model at La Cocina is changing the way business is being done—providing the necessary infrastructure for entrepreneurs to adapt and survive within a rapidly transforming economy. However, this adaptability model highlights the minimal resistance to these transformations of the Mission District's local eatery character.

What are your thoughts on intersectional models of support for homeless individuals, such as the one adopted by Dolores Street Community Services, as a perpetual force toward an equal and equitable San Francisco?

Daniel Cheung (Blueprint for Belonging Initiative): The conversations with the individuals from Dolores Street Community Services were especially powerful and impactful. The responsibility of providing services and support to homeless individuals has fallen on non-profit organizations who are consistently underfunded by the city. The state has consistently failed queer and trans individuals by not providing the resources necessary not only to survive in San Francisco, but to thrive as well.

How do you think San Francisco's local officials can improve their understanding of community needs when making decisions regarding economic development in the Mission District? And, how would you suggest historic residents of the Mission change the structure of their local legislature?

Minahil Khan (Post Elections Strategy Project): Local electeds need to address the housing crisis as an issue of civil liberties, not economic development. Council members should work with housing advocacy organizations to bring back the Speculator Tax Ballot Initiative and help pass the measure. In addition, local officials in San Francisco should refuse any campaign donations from realtors and property developers. Re. the second question, a crucial initial step would be to pass a local policy that sets up a better public finance system for all San Francisco County/City candidates. A system in which candidates cannot accept any other private donations. Candidates should also be required to live the district they are running in for five years prior to the election. It would level the playing field so that more members of the community can run for local office.

Do you think that geographical spaces aimed at fostering communal knowledge for equitable social strategies are necessary in the Mission district?

Thomas Matthew (Law Fellow): Since it is often difficult for people to find time to do independent research. Installation pieces or event spaces with an informational component could allow for shared, informal learning.