The following is a chapter from Trumpism and its Discontents. Click to download a PDF of the book here.

By Ann C. Keller

Donald Trump rose to the presidency on a wave of populism and racial resentment in the wake of President Barack Obama’s two terms.1 And while most of his populist agenda has dissolved in favor of policies benefiting corporations and the wealthy and a stream of corruption excesses among his cabinet and White House, one aspect of Trump’s populism, evidenced during his campaign, has only gained strength under his administration: his outright rejection of science and expertise.2 Trump’s efforts to undermine science at the federal level are in keeping with his disdain for expertise and his impulse-driven approach to public policy. While such a brazen lack of knowledge might be another president’s undoing, Trump’s approach is more nearly celebrated by an electoral base who have accepted the notion that expertise is elitist and either cannot or will not be applied in ways that might benefit nonelites.The Trump administration’s efforts to undermine science in the federal government, though more visible, are likely to be less consequential than the antiscience moves initiated by congressional Republicans in the mid-1990s. Although prior studies have explored how corporate actors and elected officials with antiregulatory goals have watered down policy-relevant science in order to generate policy uncertainty,3 this literature has failed to notice a more recent, and likely effective, strategy: turning off the tap. Trump’s presidency has put antiscience efforts in the headlines, but his presidency only hints at the more profound realignment among conservatives, the state, and science that is currently underway. Thus, efforts to undermine science relevant for public policy precedes the Trump presidency and will outlast it.

This chapter begins with a review of the foundations of science policy (public funding to support scientific research) and science for policy (relying on scientific analysis either for setting policy goals or for evaluating potential policy actions). Next, the chapter presents the Trump administration’s efforts to undermine science within the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) by comparing his antiregulatory efforts with those of Ronald Reagan. The chapter then describes legislative efforts to undermine federal science and argues that Trump and his political appointees have not been as extreme in their antiscience efforts as their congressional counterparts have been. The chapter explores why those progressives who hold antiscience views have not tried to decrease the presence of scientists in federal agencies or weaken the reliance on science as a precondition for setting public policy. The chapter closes by exploring the implications of the Republican party’s marrying antistate and antiscience views as core elements of conservative ideology.

The Foundations of Science and the State

Links between science and government in the United States fall into two related but distinct categories: (1) instances in which the government draws on scientific research and scientists’ expertise when setting public policy, referred to as “science-in-policy,” and (2) instances in which the government acts as the primary patron of science, or “policy for science.” The two are obviously related in that the federal funding for science creates a source of policy-relevant science that avoids the conflict of interest inherent in corporate-funded science. The idea of an alliance between science and the state runs deeply in American political history. The Founders drew their concept of democracy from Enlightenment thinking that was rooted in scientific rationalism. According to this view, democracy emerges from citizens observing the actions of elected officials and exercising their collective judgment about the validity of those actions. Jefferson, in particular, linked the idea of truth—and citizens’ particular access to it—with a functioning democracy (Ezrahi 1990: 106).4 The Founders drew a parallel between the way in which scientists gain insights about the natural world and the way in which citizens in a democracy would hold elected officials accountable.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, this philosophical commitment to science and reason was joined by financial and institutional commitments. In response to industrialization and the increasing technological complexity that came with it, Congress chartered the National Academy of Sciences in 1863 to advise the government on matters of science. The National Academy of Sciences represent an interesting partnership between government and science in that they are a nongovernmental organization that relies on public funding but draws its members from among academic scientists chosen by their colleagues to serve in the organization. It represents a formal alliance between the academy and the federal government. Fealty to science and expertise as essential ingredients of state capacity became further institutionalized during the Progressive Era, when administrative reforms replaced the system of staffing agencies via patronage with the practice of hiring according to expert and professional qualification.5

Part of the idea of being able to draw on science to guide state action or to enable state goals rested on the ability of the state to act as a patron of science. Whereas science drew most of its support from private patrons during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, by the middle of the nineteenth century that arrangement was beginning to change, particularly in the United States, where the federal government was both the largest employer of scientists and the largest funder. Moreover, the amount of public spending for science was disproportionately large, outstripping the spending on science of all European countries combined (Kelly 2014).6

While public funding for science did not completely eclipse private ventures— for instance, funding for policy research in the United States came from the March of Dimes, which organized community-level fund-raising7 —public funding of science was further consolidated in the 1950s and early 1960s during the Cold War. This consolidation, though it had multiple drivers, was articulated in Vannevar Bush’s essay “Science, the Endless Frontier.” In it, he provided an appealing account of how government-funded basic science, if left in the hands of scientists, would produce national security, economic prosperity, and cures for cancer.8 While political scientists, sociologists, and historians of science began to unravel this account,9 the notion of basic science as a pathway to the production of public goods gained widespread popularity as well as congressional acceptance.

Although members of Congress consistently supported funding for science and the use of science in policy-making during the postwar period, that support appears to have rested on a somewhat fragile consensus. On the “policy for science” side, those seeking technological innovation that would give Americans an edge in the Cold War and make the country more economically competitive tended to favor investments in the natural sciences, engineering, and mathematics while politicians who wished to tackle social issues argued for increased investments in the social sciences. This divide gave rise to congressional battles over where to house federal funding for the social sciences and how big such a budget might be.10 Though conservatives were skeptical about the idea of increased federal funding for the social sciences, a set of maligned Department of Defense- (DOD) and CIA-supported social science projects funded in the 1960s led progressives to push for increases in nonprogrammatic research dollars devoted to the social sciences. Proposals for a separate social science research foundation failed, but the debate led to increased spending on social science research under the existing National Science Foundation (NSF), even if that spending was small in comparison with spending on research in the physical sciences.11 The progressive view of social science research as policy-relevant runs counter to conservative preferences for a limited federal government, fiscal conservatism, and market-based solutions to social problems. Perhaps the small percentage of funds allocated to the social sciences satisfied conservatives, who subsequently did not feel a need to push this funding even lower.

Similarly, masked by a rhetorical fealty to science expressed by actors across the political spectrum was a long-standing ideological battle about the use of science to shape public policy. Underneath the common narrative about the need for “good science” to inform public policy were two camps: one appealing to science to close off policy debate and another appealing to science as a reason to extend policy debate. This split appeared most infamously in debates about how the government should respond to evidence that tobacco use was unhealthy. Pointing to a lack of evidence of causation in the tobacco and cancer link, tobacco industry representatives asked Congress to delay action in favor of supporting continued research.12 Even at the time, progressives participating in congressional debates characterized the call for more research as a cynical move to delay action.13 The tactic, which was wildly successful in stalling public action on tobacco, both preceded the tobacco debates and continues unabated.14 In fact, T. O. McGarity and W. E. Wagner argue that corporate attacks on the science pipeline have increased as a direct result of federal investments in science.15 Specifically, in the 1970s, riding the wave of the environmental and consumer protection movements, Congress passed a suite of statutes that created a central role for scientists and scientific research in setting federal policies designed to protect public health. These statutes also created a steady stream of federal dollars that flowed through the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Consumer Products Safety Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institution for Occupational Safety and Health, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Facing scientific research produced outside of their control, corporations and their antiregulatory allies adopted multiple strategies to create a pipeline of science that could undermine any evidence pointing to the harms to health stemming from consumer products and industrial processes.

Although progressives and conservatives had incompatible policy goals, both sides made an effort to align their positions with science as a way to try to bolster their policy goals. Borrowing a term from actor network theory, science remained an “obligatory point of passage.”16 Corporations and their allies actively sought to stall regulatory actions by funding scientific research that would call into question any findings showing harm to health associated with their products and processes. In spite of these actions, and in part because of them, regulatory battles have continued to be fought over the correct interpretation of scientific evidence,17 dollars have continued to flow to support scientific research that could be used to inform policy,18 and federal advisory committees supporting regulatory agencies continue to be filled with well-qualified experts.19

In this brief review, we can see a commitment to public funding for science and an increase in recourse to science in setting public policy, even when ideological views have led to disagreements about how to fund science and to debates about the need for regulations. Thus, we can see a long period when science has had a stable if not increasingly prominent role in government affairs. At the same time, we can also see the seeds of dissent emerging, particularly around the ends to which science might be applied.

Deregulation at the EPA during the Reagan and Trump Administrations

Though the Trump administration’s attack on public science extends beyond the Environmental Protection Agency,20 its most consistent and concerted efforts to undermine science are focused on the EPA. This section examines antiscience efforts in the context of a more general set of strategies used by conservative administrations with deregulatory policy goals.21

It is no surprise that conservative presidential administrations are more likely than progressive ones to pursue deregulation. The goal here is not to assess how presidents pursue policy goals through administrative means per se. Instead, this section calls attention to the particular way in which the Trump administration has approached science at the EPA. In comparing Trump with Reagan, two things stand out. The Trump administration’s attacks on science in the agency are more numerous, and many are likely to have impacts that outlast his presidency.

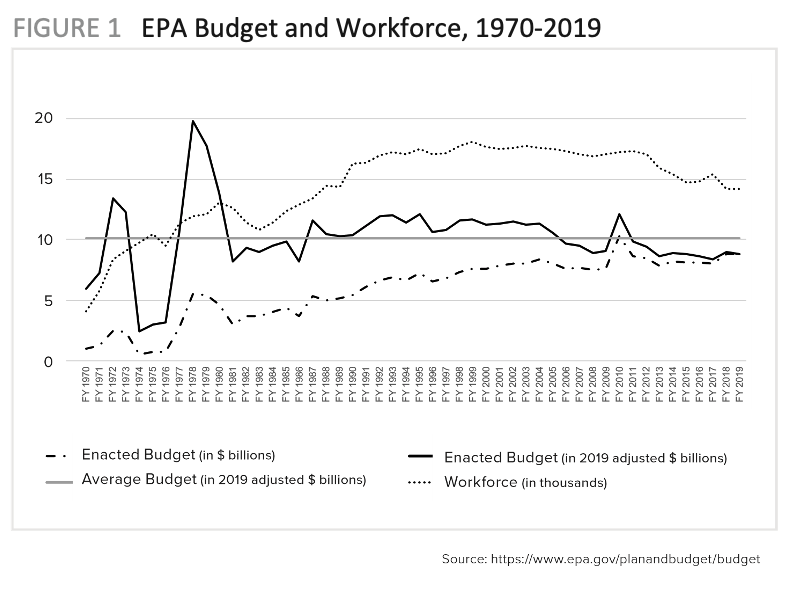

In trying to scale back EPA regulations, both administrations have pursued fewer enforcement actions against entities found to be out of compliance with environmental laws, and both sought lower penalties when violations were discovered.22 These strategies can have the effect of scaling back regulations if they signal to regulated entities that current regulations will not be enforced. Both administrations also sought to cut the EPA budget and staff—a clear effort to undermine the agency’s capacity. Presidential efforts to shape the EPA’s budget are, of course, mitigated by Congress’s power of the purse. When reviewing EPA budgets across both administrations, one finds that Reagan appears to have had more success than Trump has (see figure 1). Between fiscal years 1982 and 1987, the period during which Republicans controlled the Senate, Reagan and his GOP congressional colleagues maintained a below-average budget for the EPA. However, the largest annual cuts to the EPA budget occurred in fiscal years 1980 and 1981, before Reagan took office. These cuts were enacted by a Congress controlled by Democrats during the Carter administration and were likely a response to the steep increases in the EPA budget during the prior years (regression to the mean) and possibly to fiscal pressure caused by the recession that began in 1980. During the first three years of the Reagan presidency, the science budget at the EPA was cut in half.23 Whether Congress cut it to respond to Reagan’s policy goals or to exercise fiscal restraint is unclear.

Trump’s attempts to cut the EPA’s budget, in spite of GOP control of Congress, failed during his first two years in office. He proposed a 30 percent cut and a 23 percent cut, respectively, for FY 2018 and FY 2019.24 Congress instead increased the EPA’s budget by 10 percent in FY 2018 and held the budget stable in FY 201925 Trump’s budget proposals, though not adopted by Congress, have included cuts to the EPA’s science budget.26

In addition to their efforts to cut the agency’s budget, both administrations cut staff at the EPA (see figure 1). Reagan’s impact on the EPA workforce, however, was limited to the tenure of his first EPA administrator, Ann Burford (then Ann Gorsuch). From 1981 to 1983, the EPA’s workforce was reduced by more than 2,200 employees. Under Reagan’s second EPA administrator, William Ruckelshaus, who sought to restore the agency’s standing, the size of the EPA’s workforce began to increase. By comparison, during his first year in office, Trump cut the EPA staff by more than 1,200 employees.

In terms of efforts to roll back environmental regulations, one of Reagan’s signature efforts was to pass Executive Order No. 12291. This order required that all significant proposed regulations be sent to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for review and approval before an agency could formally propose a new rule in the Federal Register. Because no formal administrative procedures governed OMB review, the Reagan administration could indefinitely stall any rule that an agency hoped to propose.27 Moreover, the Reagan administration shared proposed rules with regulated entities and pressured agencies to rewrite proposed rules according to industry wishes before the formal process of notice and comment, during which interest groups would have to disclose their lobbying efforts publicly.28 Gorsuch also centralized agency decision-making in order to exclude career staff, a move that would have the effect of keeping scientific expertise at bay, though it did not target scientists specifically.29

For its part, the Trump administration has been aggressive in trying to scale back EPA policies that were in progress but not yet finalized during the Obama administration. Out of twenty-four environmental policies, the Trump administration has weakened or repealed seventeen, delayed two, and failed to repeal five.30 The Trump administration’s efforts, though facing court challenges, have stalled health and climate protections that would now be in effect if the Obama administration’s actions had been finalized. For example, the Trump administration’s move to overturn the current mercury standard stems from the administration’s argument against counting a regulation’s “cobenefits,” that is, the positive impacts resulting from a regulation that occur beyond the specific target of the regulation.31 If the courts uphold the Trump administration’s approach, the effects on environmental and worker health protections will extend far beyond the mercury standard itself.

While many strategies used during the Reagan administration have also been used by Trump’s EPA appointees, the Trump administration has taken several steps that particularly target science and scientists in the agency. Efforts to date include reducing the number of EPA staff combined with instituting a hiring freeze, closing scientific research offices and offering “management-directed reassignment” to employees,32 delaying scientific assessments,33 leaving top science posts at the EPA unfilled,34 eliminating science advisor positions at the EPA,35 blocking scientists who have received an EPA grant from serving on EPA science advisory boards,36 appointing individuals as science advisors to the EPA without completing an ethics review of conflict of interest documentation,37 increasing the number of scientists employed by regulated entities on EPA science advisory boards,38 and preventing the use of research to support agency rule-making if that research protects the privacy of human subjects involved in the research.39

Most of the Trump administration’s efforts vis-à-vis science at the EPA fall in line with long-standing corporate efforts to alter the pipeline of scientific research so that regulators have difficulty defending scientific evidence of health harms associated with a given product or industrial process. Policies like delaying scientific assessments and blocking the use of science that protects human subjects are likely to prevent regulators from being able to set policies based on the most recent science research findings. Taken together, several Trump administration actions—leaving scientific posts unfilled, preventing scientists who have received EPA grants from serving on EPA advisory boards, and bringing scientists into the agency who have corporate backgrounds—are likely to shift the balance of scientific expertise toward individuals who have a financial interest in preventing regulations that protect people’s health from taking force. Notably, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported a 27 percent decline in the number of academic scientists on EPA science advisory boards between January 19, 2017 and March 31, 2018.40 In addition, almost a quarter of the conflict-of-interest forms associated with the Trump administration’s new appointees to EPA science advisor positions have not been subject to an ethics review required under the Federal Advisory Committee Act.41

It is interesting to note that, while most of Trump’s cabinet-level appointees have lacked relevant expertise—something in keeping with his populist approach— both of Trump’s EPA administrators came to the position with relevant expertise. Scott Pruitt, as Ohio state attorney general, had previously sued the EPA fourteen times. At a minimum, this experience demonstrates his knowledge of both the content of EPA policies and the legal and administrative processes involved in trying to weaken them. Andrew Wheeler, a former coal industry lobbyist and deputy administrator under Pruitt, was promoted from within the agency after Pruitt was forced to resign amidst ethics scandals. Both administrators rejected scientific consensus about global warming, with Pruitt rejecting climate change outright and Wheeler arguing that its ill effects would not be felt for fifty to seventy-five years.42

In the short term, the Trump administration’s actions to undermine science at the EPA have reduced the autonomy of scientists to guide research to support current and future EPA decision-making. A subtler effect, however, is that the attacks on science themselves may be encouraging dedicated scientists to leave the EPA, representing a loss of expertise and institutional knowledge. Attacks on science at the agency can also restrict the pipeline of early career scientists willing to pursue careers at the EPA as well as the supply of more senior scientists willing to take on leadership roles. For example, the position of head of the Office of Research and Development has been vacant for eight years. The last person to hold the position, Paul Anastas, left in 2012 during the Obama administration. The GOP-controlled Senate refused to confirm Obama’s nominee to fill the post. Now, although the Trump administration is rumored to have reached out to scientists to try to fill the position, none have been willing to step in.43 Such indirect impacts could have longer-term consequences if a new administration presides over an EPA with significantly depleted in-house scientific expertise.

Turning Off the Tap

The Trump administration has drawn considerable attention for its efforts to reduce the role of science in the EPA and in the federal government more generally. Less attention has been given to the congressional actions to cut funding for federally supported scientific research that began with the 104th Congress. Cutting off federal funding for science represents a more complete break with the idea of science as providing potentially relevant input to federal policy-making. This strategy involves moving upstream to ensure that research that might be used to argue for future regulations is not conducted in the first place. Three cases in this section—firearms research at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR), and the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA)—illustrate the politics of “turning off the tap.”

In 1986, following a study published by the Surgeon General pointing to firearm ownership as a health risk and a report put out by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine calling for the CDC to lead an effort to reduce injuries in the United States, Congress gave the CDC ten million dollars to study the potential risks of firearm ownership.44 National data showed that injury is the leading cause of death in the United States for people aged one through forty-four. Further, national data on injuries and injury-related fatalities revealed that firearm injuries were the second leading cause of death, after traffic fatalities, among all injury-related deaths in the United States.45 Housed within the CDC’s Injury Prevention Branch, the program funded extramural research studying the health impacts of owning firearms. Though the program was either explicitly reviewed by Congress or its generated data was used in congressional hearings to discuss the risks of firearm ownership seven times between 1987 and 1994, none of the hearings included statements by witnesses or by Congress criticizing the CDC research program itself.46 Specifically, no witness or member of Congress argued that the federal government should refrain from funding research related to firearm ownership.

The 104th Congress, seated in January of 1995, broke a forty-year period of Democratic control of the House. With this change in leadership, a new orientation toward the CDC firearm research program emerged. Following four hearings conducted between 1996 and 1997, each of which included members of Congress and/or witnesses who criticized the firearm research program or its funded studies,47 Congress cut the budget for the program and added language stating that “[n]one of the funds made available in this title may be used, in whole or in part, to advocate [for] or promote gun control.” 48 In 2011, Congress added similar language to National Institutes of Health (NIH) appropriations. President Obama, following the shooting deaths of twenty young children at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, issued an executive order that called for the CDC to renew its research on the risks of firearm ownership. Congress, however, failed to appropriate funds to support the executive order.49

Notable about the bans on CDC and NIH research that might be used to support gun-control policies is that neither the CDC nor the NIH is an agency that has regulatory power. Moreover, the Second Amendment is a powerful tool that has been used to prevent those advocating for gun-control from achieving it, a situation that is born out in the country’s relatively weak laws governing firearms. Thus, the move against funding for research represents a notable break from past efforts to slow the pace of regulation by calling for more research. The move to cut off funding for science suggests that the members of Congress who voted for these cuts felt that scientific research, even that housed within nonregulatory agencies, would lead to new laws restricting access to firearms or might change public attitudes about ownership of firearms. Arguments for cutting the program questioned the quality of the research being funded by the CDC, the jurisdiction of the CDC to ask about firearm deaths and injuries since neither was an infectious disease, and the role of the federal government in funding such research.

One might dismiss the politics around firearm research given the Second Amendment politics that make the issue of research so salient and dramatic. However, the same Congress that cut funding for firearm research also moved to end a research program created to determine which treatments for common diagnoses work best for patients. Congress created the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) in 1990 and required that it generate evidence that could be used to improve the quality of health care. One of its programs involved creating multidisciplinary teams of expertise—Patient Outcome Research Teams, or PORTs—to review treatments for common diagnoses in order to evaluate which treatments produced the best outcomes. Between 1990 and 1996, AHCPR funded twenty-five PORTs. Based on the funded research, the agency issued nineteen new “best practices” guidelines for health-care providers and patients. These guidelines did not have the force of a regulatory action; the agency’s output merely pointed to the best treatment options for a given diagnosis. This did not prevent the guidelines from becoming controversial, as in the case of the PORT regarding treatment for low back pain that found that surgery was one of the least effective treatments for patients experiencing such pain. In 1996, surgeons mobilized to counter the PORT findings and successfully lobbied Congress to defund the agency.50 It was not until the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009 that federal funds were again allocated for comparative effectiveness research,51 ending a lack of support that had set the United States apart from all other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries in terms of investing in research to examine which medical treatments are most effective.52

The same Congress acted to close off its own pipeline for analysis of new technologies when it shuttered the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA). Bruce Bimber, in his book examining the origins, institutionalization, and termination of the OTA, maintains that antipathy for science was not a motivating factor in closing down the organization.53 Other scholars have argued that the OTA’s role in conducting assessments of health-care technologies was the factor that brought the organization under attack.54 When viewing the termination of the OTA in light of the 104th Congress’s moves against the CDC and AHCPR, Bimber’s assessment—that the termination of the OTA was a symbolic gesture demonstrating that members of Congress were willing to inflict budget cuts on themselves—is less convincing.

Those who advocated for closing down the OTA argued that the information OTA produced could come from other sources. OTA, however, because it served the US Congress, had developed an approach to generate bipartisan analysis.55 By closing the OTA, Congress removed an organization that had been under enormous institutional pressure to produce analyses that both conservatives and progressives felt served their interests. The closure suggests that the organization had failed or, given the degree of polarization, that bipartisan analysis was no longer possible. But the closure also removed an organization that was structurally designed to maintain ties with both Republicans and Democrats. In this respect, the OTA’s demise represents a profound institutional loss.

These examples of “turning off the tap” are important in that most of the literature that examines controversy in science applied to policy-making focuses on the multiple pathways for “bending” science—that is, essentially altering the mix of findings so that claims of harms to health always appear uncertain.56 This approach worked in tandem with elected conservatives who could point to the apparent uncertainties and call for more science. This strategy, while successful to a point, also appeared to have its limitations, as the sweep of state policies to curb tobacco use demonstrated.

Corporations have the resources and the financial interest in skewing the pipeline of scientific research to prevent the adoption of public policies designed to protect public health. At the same time, they must certainly prefer the strategy that emerged from Congress in the mid-1990s that terminated federally funded research programs in their entirety. This move shifted the locus of research away from the government and academia and allowed corporations and industry to decide what research would be conducted in the first place. Moreover, when congressional allies cut off public funding for policy-relevant research, they offered corporations a much cheaper and likely more effective way to achieve their antiregulatory policy goals.

Antiscience Progressives and the State

When examining the strategy of cutting off scientific research as a way to achieve regulatory policy goals, it is important to consider why this appears to be a strategy of the Right. If motivated reasoning is equally likely across the political spectrum,57 should we not see this political strategy emerge when progressives seek policy goals that run counter to an established scientific record? Two prominent issues that attract progressives with antiscience views are genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in foods and childhood vaccinations. In both cases, cutting off scientific research would preserve a status quo that these groups would like to upend. In the case of GMOs, the United States has implemented an information-based policy that requires labeling of GMO foods. This puts anti-GMO groups in the position of needing to support the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in promulgating the labeling policy. Although these groups may fault the FDA for allowing GMOs into the market, given the current state of science concerning GMO food safety, cutting off scientific research will not create an FDA more willing to ban GMO foods.

Childhood vaccination presents a similar case.58 The politics of childhood vaccination has a similar structure whereby less science does not strengthen the antivaccination position. The current scientific record shows that vaccines are safe and effective for the vast majority of children. States, arguing that vaccination is necessary to also protect the health of children who cannot be safely vaccinated—that is, those with compromised immune systems, are instituting policies that prevent parents from being able to claim personal beliefs as a reason to not have their children vaccinated. Although it rests on a disagreement concerning the scientific record, the fight about these policies is not being carried out over the funding of research. In California, for example, parents who do not wish to have their children vaccinated are looking for pediatricians who will write requests for unfounded medical exemptions while the state and the state medical board are taking punitive actions against pediatricians determined to have written medically unnecessary exemptions. In fact, in many cases, parents may seek more research on vaccine effects to try to find evidence that will substantiate a medical reason for avoiding their children’s vaccination.

Implications of antiscience efforts at Trump’s EPA

This analysis places Trump’s attacks on science in the EPA in a broader context of efforts on the part of conservatives to scale back regulations that protect people’s health. Trump’s appointees at the EPA are working on several fronts to shift the locus of science from academics to corporate and industry-based science. Taken together, the Trump administration’s actions combine elements of “bending” science with efforts to restrict the flow of both science and scientists to the agency. It is interesting to note, however, the line that the Trump administration has not crossed. Political appointees to the EPA continue to claim that their efforts are intended to improve science at the EPA.59 Thus, although Trump administration officials publicly discount scientific claims, they are not quite willing to say that there is no need for science to support EPA decision-making. Nor are they willing to engage in a frontal assault on EPA research programs by arguing that there is no legitimate place for publicly funded scientific research. While Trump, in his willingness to defend his latest policy position with outright lies, appears as a particularly strident opponent of science-informed policy, the quiet dissolution of federally funded science by Congress represents a more fundamental break with the long-standing government–science alliance in the United States.

Looming over analyses of Trump and Trumpism is the question of legacy. Trump and his administration have undermined the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to set public health standards based on the most current science. Unlike Reagan, whose efforts focused mostly on slowing down the pace of regulation and enforcement without touching science at the EPA, the Trump administration has multiple efforts underway to bend science—that is, increasing the presence of industry scientists serving on EPA advisory boards—and to limit the agency’s access to new scientific information. At the same time, the Trump administration has stopped short of announcing that there is no need for science to support EPA decision-making. Considering the potential long-term effects of the Trump administration’s efforts, it is likely that a new administration will be handed a hamstrung EPA. For a future president who would like to see the EPA drawing from the latest scientific research when setting EPA rules, it may be years before the agency is restored to its pre-Trump capacity.

One possible outcome of the Trump administration’s efforts could strengthen science at the EPA. The practice of placing corporate and conservative scientists on advisory boards is an effort to further tip the scales away from research that indicates harm caused by products and industrial processes. Making advisory boards more friendly to corporate interests is likely to have this effect. At the same time, advisory board membership is not simply a one-way street from corporate boardrooms to federal regulatory agencies. Membership on such federal advisory boards can create information flows in the opposite direction. In fact, the National Research Council (NRC) has a policy that requires “balanced” membership on its research panels.60 One effect of having balanced panels is that inclusive panelist representation sends a signal back to communities that might otherwise dismiss NRC research. If a member of your community served on an NRC panel and that community member stands by the panel’s final report, that assurance can create confidence in the report’s findings that might otherwise be absent. Nevertheless, balanced research panels are not a panacea, and disagreements among panel members can still interrupt panel work.61 Moreover, no one should serve on any federal agency board without having gone through a thorough vetting of potential conflicts of interest. However, in an era of hyperpolarization, advisory boards that bring conservatives and progressives together through formal processes to create guidance for federal policy-makers could generate conversations not happening elsewhere.

The Trump administration’s antiscience efforts could also generate a backlash. Many reviewers of Donald Trump’s presidency worry that his conduct in office will normalize much of his worst behavior as acceptable for American politicians. It certainly is possible that future elected officials may feel less constrained by facts and evidence. But it is equally possible that the public may refuse to give credence to elected officials who dismiss well-supported and long-standing scientific findings.

Senior Emma Gonzales’s response to elected officials—“we call BS”—after the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shows what this might look like.

A Seismic Shift

The Trump administration has drawn a great deal of attention to the issue of how conservatives view science. However, regardless of whether or not this approach stimulates a backlash, the presidency is not the only place where antistate and antiscience views can undermine the federal government’s capacity to protect public health. Across many institutions of government, conservatives are working systematically to ensure that less science is available for policy-making. Responding to the enactment of a sweep of regulations that followed the rise of the environmental and consumer protection movements, conservatives have altered their strategies for scaling back or stalling regulatory actions. Former calls for more research are now being replaced with calls for no research and a willingness to question the role of the federal government in funding science-for-policy in the first place.

Since we are so accustomed to partisan debates over whether some chemical, toxic substance, industrial process, or product does or does not cause harm to humans or the environment, the shift from bending science to turning off the tap might look like an incremental step in a long-standing ideological schism. Instead, the move to cut off federal funding for policy-relevant science represents a profound break in a government–science alliance that had previously existed for more than two hundred years. It represents a shift not only in the country’s orientation toward science but also its attitude toward academics, who are now viewed through a partisan lens, and toward the government’s role in protecting public health. Given the technological and scientific complexity of life in the twenty-first century, reducing the scientific and technical capacity of the federal government is likely to have profound consequences.

- 1M. Hooghe and R. Dassonneville, “Explaining the Trump Vote: The Effect of Racist Resentment and Anti-immigrant Sentiments,” PS: Political Science and Politics 51, no. 3 (2018): 528–34.

- 2D. Matthews, “You’ll Learn More about Trump by Looking at His New Website than Listening to His Speech,” Vox, Jan. 20, 2017, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/1/20/14338640/donald-trump…; P. Blumenthal, “Trump’s Record of Ethically Tainted Cabinet Departures Rises with Acosta’s Exit,” Huffington Post, July 12, 2019, https://www. huffpost.com/entry/trump-cabinet-ethics;J. Wolfe, “U.S. House Panel Launches Investigation of Transportation Chief Chao,” Reuters, Sept. 16, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-congress-chao/u-s-house-panel-la…; D. Leonhardt and P. Philbrick, “Trump’s Corruption: The Definitive List: The Many Ways That the President, His Family, and His Aides Are Lining Their Own Pockets,” Opinions, New York Times, Oct. 28, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/28/opinion/trump-administration-corrupt…; J. E. Oliver and W. M. Rahn, “Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 Election,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667, no. 1 (2016): 189–206.

- 3T. O. McGarity and W. E. Wagner, Bending Science: How Special Interests Corrupt Public Health Research (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); D. Michaels, Doubt Is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); D. Michaels, and C. Monforton, “Manufacturing Uncertainty: Contested Science and the Protection of the Public’s Health and Environment,” American Journal of Public Health 95, no. S1 (2005): S39–S48; N. Oreskes and E. M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2011).

- 4Y. Ezrahi, The Descent of Icarus: Science and the Transformation of Contemporary Democracy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), p. 106.

- 5J. Knott and G. Miller, Reforming Bureaucracy: The Politics of Institutional Choice (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1987); A. Kelly, “The Political Development of Scientific Capacity in the United States,” Studies in American Political Development 28, no. 1 (2014):1–25.

- 6A. Kelly, “Political Development of Scientific Capacity,” 1–25.

- 7D. M. Oshinsky, Polio: An American Story (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- 8V. Bush, Science, the Endless Frontier: A Report to the President (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1945).

- 9D. Nelkin, “The Political Impact of Technical Expertise,” Social Studies of Science 5, no. 1(1975), 35–54; J. R. Primack and F. Von Hippel, Advice and Dissent: Scientists in the Political Arena (New York: Basic Books, 1974); D. Price, “Endless Frontier or Bureaucratic Morass?,” Daedalus 107, no. 2 (1978): 75–92, retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024546; A. M. Weinberg, “Science and Trans-science,” Minerva 10, no. 2 (1972): 209–22.

- 10Mark Solovey, 2012. “Senator Fred Harris’s National Social Science Foundation Proposal: Reconsidering Federal Science Policy, Natural Science–Social Science Relations, and American Liberalism during the 1960s,” Isis 103: 54–82.

- 11Ibid.

- 12House Committee on Government Operations (HCGO), False and Misleading Advertising (Filter-Tip Cigarettes): Hearing before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives, 85th Cong., 1st Sess. (1957); House Committee on Agriculture (HCA), Tobacco Research Laboratory: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Tobacco of the Committee on Agriculture, House of Representatives. 88th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1964).

- 13HCA, Tobacco Research Laboratory.

- 14Michaels, Doubt Is Their Product; Michaels and Monforton, “Manufacturing Uncertainty: Contested Science,” S39–S48; Oreskes and Conway, Merchants of Doubt.

- 15McGarity and Wagner, Bending Science., p. 24.

- 16Michel Callon, “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay.” The Sociological Review 32, no.1 supple (1984): 202-204.

- 17S. Jasanoff, The Fifth Branch: Science Advisers as Policymakers (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990); S. Jasanoff, “Skinning Scientific Cats,” New Statesman and Society 26 (February): 29-30; Ann C. Keller, Science in Environmental Policy: The Politics of Objective Advice (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009); R. Shep Melnick, Regulation and the Courts: The Case of the Clean Air Act (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1983).

- 18Ann C. Keller, “Credibility and Relevance in Environmental Policy: Measuring Strategies and Performance among Science Assessment Organizations,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20, no. 2 (2009): 357–386.

- 19S. Hilgartner, Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000); Jasanoff, Fifth Branch: Science Advisers.

- 20For example, recent efforts to push scientists and seasoned regulators from their posts in Washington DC to Midwestern and Western states have been criticized as an effort to force subject-matter experts to resign. Merrit Kennedy, “Scientists Desert USDA as Agency Relocates to Kansas City Area,” National Public Radio, July 17, 2019.

- 21For the sake of length, I am not covering the George W. Bush administration. Briefly, Bush did pursue antiregulatory goals at the EPA, including a failed effort to weaken the standard for arsenic in drinking water. (See K. Seelye, “EPA to Adopt Clinton Arsenic Standard,” New York Times, Nov. 1, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/11/01/us/epa-to-adopt-clinton-arsenic-stan…. html.) Other similar goals pursued included his failed Clear Skies proposal and his successful effort to prevent the EPA from enforcing New Source Review. (See B. Barcott, “Changing All the Rules,” New York Times, Apr. 4, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/04/magazine/changing-all-the-rules.html.) And although Bush was criticized as being antiscience, most of his efforts represented visible clashes that pitted his administration against the science community, with his administration ultimately backing down. For example, the controversy at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) surrounding access to the emergency contraceptive Plan B delayed over-the-counter approval of the drug by two years. An effort to water down an EPA report that contained information about climate change led to agency officials removing the section on climate change and then leaking the reason for the omission in the report to the press. The Bush administration tried to limit public statements by federal scientists on climate change, but did an about-face when James Hansen spoke to the New York Times about the censorship coming from the administration. (See A. Revikin, “Climate Expert Says NASA Tried to Silence Him,” New York Times, Jan. 29, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/29/science/earth/ climate--expert-says-nasa-tried-to-silence-him.html; A. Revikin, “NASA Chief Backs Agency Openness,” New York Times, Feb. 4, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/04/science/nasa-chief-backs-agency-open….)

- 22M. M. Golden, What Motivates Bureaucrats?: Politics and Administration during the Reagan Years (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); E. Lipton and D. Ivory, “Under Trump, EPA Has Slowed Actions against Polluters and Put Limits on Enforcement Officers,” New York Times, Dec. 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/10/us/politics/pollution-epa-regulation….

- 23M. Kraft and N. Vig, “Environmental Policy in the Reagan Presidency,” Political Science Quarterly 99, no. 3 (1984): 430.

- 24US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), FY 2018 EPA Budget in Brief, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Report No. EPA190-K-17-001, May 2017; US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), FY 2019 EPA Budget in Brief, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Report No. EPA-190- R-18-002, Feb. 2018.

- 25M. Koren, “Congress Ignores Trump’s Priorities for Science Funding,” Atlantic, Mar. 23, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/03/trump-science-budge….

- 26US Government Accountability Office (USGAO), High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas, Report No. GAO-19-157SP, Mar. 2019, 204, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/697245.pdf.

- 27Golden, What Motivates Bureaucrats?, pp. 118-119; Kraft and Vig, “Environmental Policy in the Reagan Presidency,” p. 432.

- 28Kraft and Vig, “Environmental Policy in the Reagan Presidency,” p. 432.

- 29Golden, What Motivates Bureaucrats?, p. 122.

- 30Data were obtained from the Brookings Institution’s interactive tracking website titled “Tracking Deregulation in the Trump Era.” See: https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/tracking-deregulation-in-the-tru…. For perspective, the Federal Register lists 253 significant rules passed by the EPA during the Obama administration.

- 31C. Raso, Examining the EPA’s Proposal to Exclude Co-Benefits of Mercury Regulation, Series on Regulatory Process and Perspective (Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/research/examining-the-epas-proposal-to-exclu….

- 32Eric Katz, “EPA to Close a Las Vegas Office, Reassign Employees,” Government Executive, July 30, 2019, https://www.govexec.com/workforce/2019/07/epa-close-las-vegas-office-re….

- 33US Government Accountability Office (USGAO). High-Risk Series: Substantial Efforts Needed to Achieve Greater Progress on High-Risk Areas, Report No. GAO-19-157SP, Mar. 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/697245.pdf.

- 34Robin Bravender, “Embattled Science Office: Six Years with No Confirmed Leader,” Energy and Environment News: Greenwire, Aug. 24, 2018, https://www.eenews.net/stories/1060095083; Coral Davenport, “In the Trump Administration, Science Is Unwelcome. So Is Advice,” New York Times, June 9, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/09/climate/trump-administration-science….

- 35Coral Davenport, “EPA to Eliminate Office That Advises Agency Chief on Science,” New York Times, Sept. 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/27/climate/epa-science-adviser.html.

- 36Timothy Cama, “EPA Blocks Scientists Who Get Grants From Its Advisory Boards,” Hill, Oct. 31, 2017, https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/358043-epa-blocks-scienti…; Lisa Friedman, “Pruitt Bars Some Scientists from Advising EPA,” New York Times, Oct. 31, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/31/climate/pruitt-epa-science-advisory-…; Jonathan Stempel, “US EPA Is Sued for Ousting Scientists from Advisory Committees,” Reuters, June 3, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-epa-lawsuit/us-epa-is-sued-for-ousti….

- 37US Government Accountability Office (USGAO), EPA Advisory Committees: Improvements Needed for the Member Appointment Process, Report No. GAO19-280, July 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/700171.pdf.

- 38Cama, “EPA Blocks Scientists”; Friedman, “Pruitt Bars Some Scientists”; Stempel, “US EPA Is Sued.”

- 39Josh Siegel, “EPA Announces Major Reorganization Plan for Science Research Office,” Washington Examiner, Mar. 7, 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/energy/epa-announces-major-re….

- 40US Government Accountability Office (USGAO). “EPA Advisory Committees: Improvements Needed for the Member Appointment Process,” Report No. GAO-19-280, July 2019,https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/700171.pdf., pp. 22-23

- 41Ibid., p. 33.

- 42Z. Budryk, “EPA Head Says Climate Change Threat 50–75 Years Out,” Hill, 2019, accessed June 25, 2019, https://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/434884-epa-head-says-clim….

- 43Bravender, “Embattled Science Office.”

- 44US Surgeon General, Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1979); National Research Council, Injury in America: A Continuing Public Health Problem (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1985).

- 45K. E. Gotsch, J. L. Annest, J. A. Mercy, and G.W. Ryan, “Surveillance for Fatal and Nonfatal Firearm-Related Injuries—United States, 1993–1998,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 50 (2001): 1-32.

- 46Ann C. Keller, S. Burrowes, R. Flagg, and G. Goldstein, “Credibility as Liability: Wing-Clipping at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention” (paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC, Aug. 28–31, 2014).

- 47Ibid.

- 48A. Rostron, “The Dickey Amendment on Federal Funding for Research on Gun Violence: A Legal Dissection,” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 7 (2018): 866, doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304450.

- 49E. Frankel, “Why the CDC Still Isn’t Researching Gun Violence, Despite the Ban Being Lifted Two Years Ago,” Washington Post, Jan. 14, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/storyline/wp/2015/01/14/why-the-cdc….

- 50B. H. Gray, M. K. Gusmano, and S. R. Collins, “AHCPR and the Changing Politics of Health Services Research: Lessons from the Falling and Rising Political Fortunes of the Nation’s Leading Health Services Research Agency,” Health Affairs 22, Suppl.1 (2003): W3–297-W3-298; Ann C. Keller, R. Flagg, J. Keller, and S. Ravi, “Impossible Politics? PCORI and the Search for Publicly Funded Comparative Effectiveness Research in the United States,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 44, no. 2 (2019): 225, doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-7277368.

- 51Keller et al., “Impossible Politics?” p, 225.

- 52K. Chalkidou, S. Tunis, R. Lopert, L. Rochaix, P. T. Sawicki, M. Nasser, and B. Xerri, “Comparative Effectiveness Research and Evidence-Based Health Policy: Experience from Four Countries,” Milbank Quarterly 87 (2009): 339–67, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00560.x.

- 53Bruce A. Bimber, The Politics of Expertise in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Office of Technology Assessment (Albany: SUNY Press, 1996).

- 54Corinna Sorenson, Michael K. Gusmano, and Adam Oliver, “The Politics of Comparative Effectiveness Research: Lessons from Recent History,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 39, no. 1 (2014): 139–70.

- 55Bimber, Politics of Expertise in Congress.

- 56McGarity and Wagner, Bending Science; Michaels, Doubt Is Their Product; Michaels and Monforton, “Manufacturing Uncertainty: Contested Science”; Oreskes and Conway, Merchants of Doubt.

- 57P. W. Kraft, M. Lodge, and C. S Taber, “Why People Don’t Trust the Evidence: Motivated Reasoning and Scientific Beliefs.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 658, no. 1 (2015): 121–33, doi.org/10.1177/0002716214554758; J. Kahne and B. Bowyer, “Educating for Democracy in a Partisan Age: Confronting the Challenges of Motivated Reasoning and Misinformation,” American Educational Research Journal 54, no. 1(2017): 3–34, doi.org/10.3102/0002831216679817; G. Pennycook and D. G. Rand, “Lazy, not Biased: Susceptibility to Partisan Fake News Is Better Explained by Lack of Reasoning Than by Motivated Reasoning,” Cognition 188 (2019): 39–50.

- 58While many science issues—like climate change and firearm ownership—are shaped by ideological and partisan identities, belief in the idea that childhood vaccination might be harmful cuts across the political divide. Pew Research Center, “Vast Majority of Americans Say Benefits of Childhood Vaccines Outweigh Risks,” Pew Research Center Science and Society, Feb. 2, 2017, https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2017/02/02/vast-majority-of-america….

- 59Josh Siegel, “EPA Announces Major Reorganization Plan for Science Research Office,” Washington Examiner, Mar. 7, 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer. com/policy/energy/epa-announces-major-reorganization-plan-for-science-research-office.

- 60Ann C. Keller, “Credibility and Relevance in Environmental Policy: Measuring Strategies and Performance among Science Assessment Organizations,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 20, no. 2 (2009): 368.

- 61S. Hilgartner, Science on Stage: Expert Advice as Public Drama (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000).