An ordinance recently passed in Richmond, California, shows a new pathway to ensure that major economic development projects in low-income communities of color are designed for more equitable benefits by delivering local jobs, inclusive hiring, and contributions toward affordable housing and other community-identified projects. The local law is an important milestone in a movement advanced in cities around the country to secure community benefits agreements and other forms of binding commitments to equitable development. Rather than negotiate agreements with developers on a project-by-project basis, an enormous task where local communities are often overpowered by deep-pocketed developers, Richmond now has a baseline of benefits required for all projects, public reporting specifying the benefits of a project before it is approved by the city, and a public process for input and a city council vote on the community benefits commitments.

The context for the new law is a history, not unique to Richmond, of development projects that made grand promises of local jobs, small business contracts, public space and other benefits that never materialized. Worse yet is a common practice by city officials who use inside information and their ability to block or slow development projects in order to secure campaign donations, lucrative contracts for their own business, and other favors. For their part, too many developers have a business model that amounts to monetizing public investments and approvals. They use their connections to local officials to secure public subsidies like discounted land, tax breaks, grants and infrastructure improvements, which increase the value of their land. The increased land value is then used as collateral to access low cost capital, or the property is simply sold at a profit.

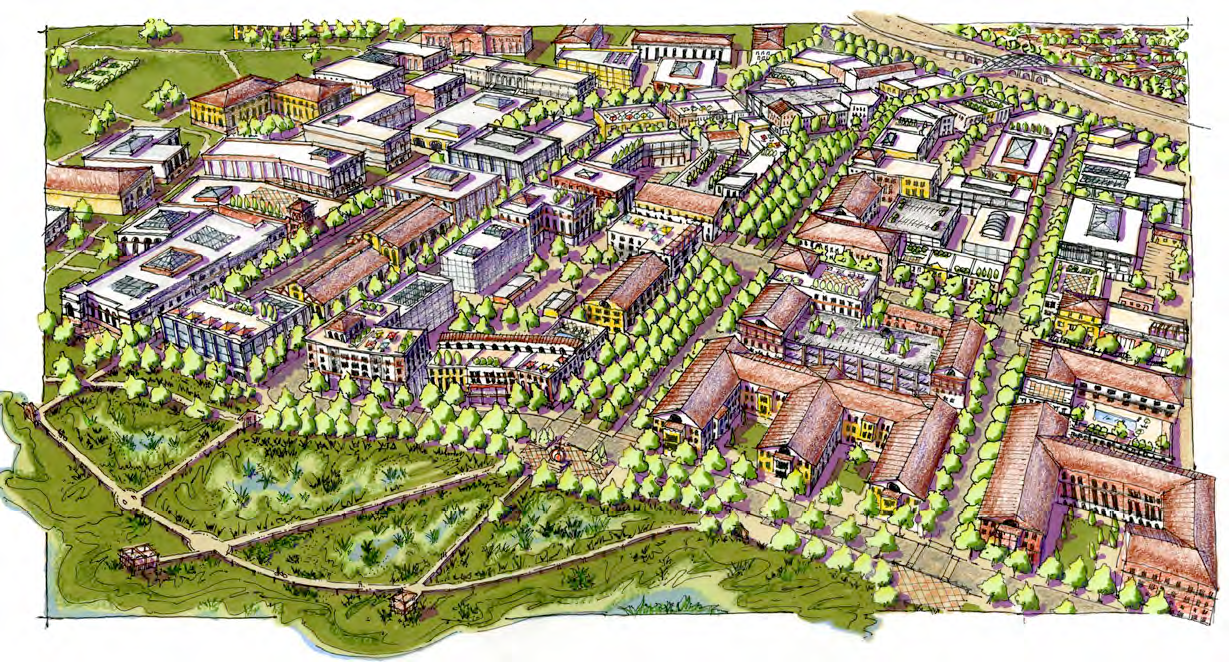

The response of many communities harmed by this extractive system of economic development has been to organize coalitions and demand commitments to specific actions by developers and local officials to meet needs for local employment, living wages, affordable housing, and other priorities. Such was the case in Richmond several years ago when the University of California at Berkeley proposed to build a new campus in the city. Although the public university’s project was on public land, the campus plan was to lease the land to a private developer, and use private investments to finance the project. A coalition of community groups and unions calling themselves “Raise up Richmond” organized and pressured the university to commit to a community benefits plan. Through a collaborative process lasting more than a year, the university and the coalition created a detailed community benefits plan. But just months later, the chancellor resigned and with no financing and no champion to advance it, and the campus project died. However, the coalition had worked with the city to institutionalize the community benefits requirements in a neighborhood Specific Plan (see Section 6.6), a city plan that sets development requirements for a neighborhood. The Othering and Belonging Institute (at the time known as the Haas Institute) provided technical, policy and legal assistance to the community coalition (e.g. see this Anchor Richmond report).

This year, the progressive majority on Richmond’s city council took the community benefits element of the Specific Plan and turned it into a city-wide policy. The council and city staff worked with Julian Gross and Estolano Advisors, community benefits experts who have worked across the country, to draft the policy. The progressive council members already had a record of holding developers accountable for projects with faulty environmental clean-up plans, public costs that outweigh new revenue, and questionable backroom deals.

Key elements of the new policy cover both the city’s process for approving projects, and the specific commitments that developers must make before approval. The law applies to all projects that involve a “public-private partnership,” which is defined as any project that will use public land, subsidies, or involve a development agreement. Development agreements are typical of large projects because they provide certainty to the developer that the city will fulfill specific roles with defined timelines. For all such projects, the developer is now required to provide a public document detailing community benefits commitments that the city will make public at least two weeks before a city hearing to approve the project. Basic commitments that must be included in the plan are to hire local residents (at least 25 percent of total work hours and new hires), abide by the city’s Fair Chance Hiring policy (access to employment for formerly incarcerated workers), pay living wages, contract with local small businesses, and contribute funds to the city’s community benefits fund (amount to be negotiated).

While the new policy raises the bar for equitable economic development, there are important limits and areas for remaining work that should be noted. Firstly, as an ordinance adopted by the city council, the law can be overturned, and projects can be granted an exemption any time with a vote of the council. Having leadership on the city council that supports equitable and accountable development will still be needed.

A limit of this policy and community benefits agreements in general is that the city and community do not have access to all the financial information about a project's costs and revenues, and thus are at a disadvantage when confronted with developers’ frequent claims that they cannot afford certain community benefits. Development enterprises that build community benefits and local leadership into their mission and governance structure transcend this challenge by giving community leadership and social equity inside access to financial information and decision making. Organizations like Restore Oakland, Richmond LAND, and East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative are examples of how this can work.

Another area for further work is to expand the practice and structures for reparative investment that can provide financing with rates and priorities aligned with equitable development projects. The recent closure of Community Foods Market, the only full service grocery store in West Oakland and a business applying social equity across its operations, shows that even the small number of such enterprises are not matched by an availability of financing that is patient and principled enough to sustain their growth.

Moving towards an economy where all belong means structuring local investment and development so that it reverses disinvestment without catalyzing displacement. Equitable development policies like Richmond’s are a step toward setting the rules so that the benefits of investment are widely enjoyed and meet the needs of communities who have historically been the most often left out or harmed by development.

Editor's note: The ideas expressed in this blog post are not necessarily those of the Othering & Belonging Institute or UC Berkeley, but belong to the author.