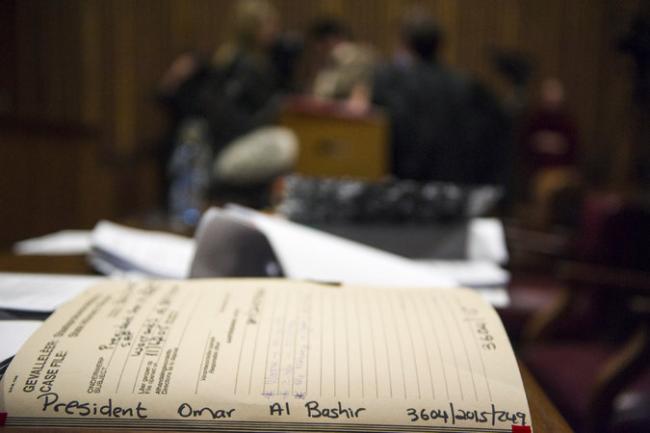

Aug. 18, 2015—On June 15th, the Sudanese president Omar Hassan Ahmad Al-Bashir flew out of South Africa, defying a local court order and international indictment against him by the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Human rights advocates around the world accused the South African government and the African Union leaders of being conspirators who sided with an internationally indicted individual. However, many African leaders and members of the African National Congress (the ruling party in South Africa) fired back by accusing the ICC of being racist by singling out Africa. They based their assertion on the fact that since its inception in 2002, the ICC has heard 22 cases and accused 32 individuals - all of them Africans.

Since the ICC issued its first arrest warrant in March 2009 against the Sudanese president for war crimes and crimes against humanity, the debate on retributive justice and the question of responsibility to protect has divided human rights and social justice activists. According to the ICC, Al-Bashir “is suspected of being criminally responsible, as an indirect (co-perpetrator), for intentionally directing attacks against an important part of the civilian population of Darfur, Sudan, murdering, exterminating, raping, torturing and forcibly transferring large numbers of civilians, and pillaging their property.”

Today, six years after the indictment, the situation in Darfur has only worsened, which begs the question: what is important to pursue: retributive justice or peace and reconciliation? Can we have one without the other? Can we have either without understanding the historical context of the conflict?

In terms of retributive justice (or justice before peace) as a framework to end Darfur atrocities, a number of people around the world have applauded the ICC’s decision (among them many African citizens). Others hesitate to join the euphoria, characterizing it as a defeat of its purpose to protect innocent civilians in Darfur. One reason for their hesitation is the concern that the idea of punishment superseded peace and reconciliation processes. In addition, the latter voiced their skepticism on the selective nature of the ICC’s cases, arguing that the ICC has all its open cases on the African continent.

Today, six years after the indictment, the situation in Darfur has only worsened, which begs the question: what is important to pursue: retributive justice or peace and reconciliation? Can we have one without the other? Can we have either without understanding the historical context of the conflict?

Those who supported the ICC indictment, by focusing on the pursuit of retributive justice and the “responsibility to protect,” should look at the current situation in Darfur and notice what the indictment has done thus far in terms of “saving” people’s lives. The ICC indictment lacks fundamental premises, which revolve around questions of credibility, accountability and the possible misuse of interventionist approaches in which harm appears much greater than the reduction of misery experienced by the Darfuri people. While the political reform in Sudan has stagnated, and the fact that the president of Sudan freely travels through international airspace to neighboring countries, as well as the fact that the Sudanese regime continues to receive unconditional support from major regional and international actors, for geopolitical and natural resources reasons, despite his criminal record, puts the credibility of the ICC in jeopardy.

Critics of the International Criminal Court’s indictment and its former chief prosecutor, Mr. Luis Moreno Ocampo, perceive the indictment as politically motivated, and have expressed resentment towards what has been dubbed as double standards for Global South countries. Others have suggested that the ICC should have addressed other conflicts (e.g. the Israeli occupation of Palestine since 1967 and crimes committed thereafter, and the United States invasion and occupation of Iraq, etc.) in terms of the international community’s “responsibility to protect.” Moreover, a number of prominent observers have questioned the credibility of the former chief prosecutor of the ICC, who pursued the charges against Al-Bashir, and his investigation methodology.

For example, in 2009, the African Union, the Arab League, the Organization of the Islamic Conference, and the Group of 77 — an influential United Nations bloc of Global South nations — have all condemned the timing of the indictment, and characterized it as “counterproductive” to the peace efforts in Darfur. Moreover, two members of the Security Council of the United Nations, China and Russia, have already expressed "serious concern" over the indictment. Furthermore, prominent African scholar Mahmood Mamdani has argued that ending conflicts in Africa does not mean the mechanical application of prosecution. He points out that major African conflicts reached settlement and political reform without prosecutions, such as those of South Africa, Mozambique, and South Sudan. He believes “if peace and justice are to be complementary rather than conflicting objectives, we must distinguish victors’ justice from survivors’ justice…in a situation where there is no winner and thus no possibility of victors’ justice, survivors’ justice may indeed be the only form of justice possible.”

In fact, many critics have questioned Ocampo’s estimates of death figures and characterized them by stating that the “arithmetic is simply fantastical.” For example, Julie Flint and Alex de Waal pointed out “There is much speculation, inside and outside of the ICC, at how Moreno Ocampo arrived at his figures for death rates in Darfur.” Additionally, in their World Affairs’ article, Flint and de Waal argued, “Moreno Ocampo had scraped through. The drama, however, revealed a recurrent weakness: the Prosecutor had cut corners. He had orchestrated a drumbeat of public expectation, setting trial dates before his case was ready. Moreno Ocampo was preoccupied with the wrong court – the court of public opinion.” Other international authorities familiar with international conflicts and human rights violations agreed. Antonio Cassese “assailed every aspect of Moreno Ocampo’s investigations, but especially his failure to undertake even ‘targeted and brief interviews’ in Darfur.” Furthermore, according to Flint and de Waal’s article, the former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour, criticized Ocampo for his poor performance in the conduction of a viable investigation on the ground; Arbour avowed that “Moreno Ocampo was proceeding [in his investigation] down the wrong track.”However, whether Al-Bashir has been arrested or not, the people and the region of Darfur are still yearning for peace, democratization, equal representation and political stability. Thus, the focus should be on navigating the possibilities to put an end to this tragedy by implementing political reform in Sudan, and to do that we must understand the history and the roots of the Darfur conflict. Most observers in European and U.S. capitals have established the year 2003 as a baseline for the Darfur conflict and supported the chief prosecutor of the ICC’s claims that the government of Sudan had “systematically” attacked refugee camps in order to “eliminate the African tribes;” yet, Ocampo did not provide convincing evidence to the court with regards to the three allegations of genocide charges against Al-Bashir, leading to the rejection of all three counts by the judges of the ICC. On the contrary, much of the present-day complexities of the Darfur conflict are rooted in the history of colonial Sudan. The conflict can be traced to the colonial British administration’s effort during the 1920s to create two confederations in the Darfur region, based on racializing the region’s inhabitants: the pastoralist Arabic speaking (Arab) groups vs. Zurga (dark-skinned) non-Arab, sedentary farmers.

However, whether Al-Bashir has been arrested or not, the people and the region of Darfur are still yearning for peace, democratization, equal representation and political stability.

The implication of such racialization of the Darfuri people, as well as the effects of climate change (desertification), land ownership, and the Chadian civil war of 1980s (which carried out as a proxy standoff of the Cold War between the US and USSR) and spilled over into Darfur. In totality, all these factors contributed to devastated circumstances visible in the erosion of public infrastructures and rule of law, and excluding the region from any national development plans.

Such outcomes create the ripe conditions for antagonistic relationships and constant clashes among the diverse ethnic and sub-ethnic groups of the region, ultimately leading to the eruption of the first civil war in Darfur between the years of 1987 and 1989. This war was fought along these ethnic lines due to limited resources and marginality long before the arrival of Al-Bashir to power. Al-Bashir and the political Islam party (called the National Islamic Front until 1999, and then the National Congress) overthrew the democratically elected government on a coup d’état in June 1989.

Historically, the socioeconomic and political realities in the Darfur region – and in Sudan as a whole – have been racialized by deliberate and systematic policies of colonial Britain, in particular policies related to land ownership and land reforms in post-independence. These racialized policies, which were carried out after independence by the Sudanese elite, have created great social stratification in Sudanese society. The Zurga and other ethnic minorities in Sudan have been highly marginalized and oppressed; their only option was to fight constantly against the status quo in order to gain equal access to political representation, socioeconomic rights, wealth sharing, and inclusion.

When colonial Britain left the country in 1956, the elite-Arabized ruling class (different from simply Arab) continued the colonial policies that intensified social stratification and marginality. In 1989, political Islam government managed to add another dividing dimension to the conflict: religion. The result was a destructive war against the South intended to assimilate the indigenous population of South Sudan into the elite-center class, a project referred to as the “civilizing project” of the Sudanese society. The irony is obvious in ways in which the elite choose to name their national project 'civilizing project' which, in essence, very similar to the colonial one's 'civilizing mission'.

While the inhabitants of the Darfur region were/are Muslims and speak Arabic, most of their leadership (Arab and Zurga) fought alongside the Arabized-elite government of the center, against the South. That war ended after 17 years with a defeat of the elite-center project. Nonetheless, the ruling elite did not give up on their long-dreamed project. In 1983, the dictatorial regime of Gaafar Nimeiry (1969-1985) abandoned the peace of the Addis Ababa Accords of 1972 — which had been signed with the Southern rebel movement of Anyanya I — and launched a bloodier civil war to assure its hegemony in the southern region. Devastatingly, the following 22 years of civil war cost the country over 2 million deaths, more than 4 million internally displaced persons, severe social regression, economic setbacks, and massive physical destruction. Nevertheless, the Arabized-elite’s project failed yet again.

The Darfur conflict was born out of this long history of struggle around national identity, power relations, governing systems, and international interventions in Sudanese affairs by world and regional powers. Hence, for many Western observers (including Ocampo) to suggest that there is an absence of colonial footprints in the genesis of, and understanding the antagonistic relationship between center and periphery (e.g. elite and marginalized population), is duplicitous. Additionally, to imply that many of the rebel groups and the Sudanese regime are ideological opposites ignore the political reality of Sudan. For example, Ibrahim Khalil — the leader of Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) who was killed in 2011 by the Sudanese Army — was one of the most active leaders of the political Islam movement (PIM) in the Sudanese regime up until 1999, when the PIM movement split as a result of a power struggle.

The Darfur conflict was born out of this long history of struggle around national identity, power relations, governing systems, and international interventions in Sudanese affairs by world and regional powers.

Indisputably, the regime of Al-Bashir and the political Islam movement in Sudan bear the ultimate responsibility for the brutality in Darfur and other parts of the country by drawing upon the racialized colonial policies of the last century. Yet JEM and other rebel groups’ leaders bear shared responsibility for the crimes committed against the Darfuri people as well. To spare them from the indictment is unjustifiable by “the responsibility to protect” standards.

Furthermore, the ICC chief prosecutor’s suggestion that the Darfur conflict is based solely on the racialized dimension of the region’s inhabitants (Arabs vs. Africans) is entirely a departure from the reality of the Sudanese demographic, environmental, and political landscape.

Undoubtedly, the question that re-emerges here is whether the indictment has protected and/or brought peace and security to the people of Darfur, to the region, and /or to the Republic of Sudan. Six years after the indictment, the answer is categorically, no. The former chief prosecutor of the ICC, Ocampo, may have even become an obstacle to peace negotiations, at the time of indictment, between the government of Sudan and the major rebel movement. Thus, contributed to status of no peace and no security in Darfur. When asked by Foreign Policy: “Could the pursuit of justice result in the exacerbation of atrocities or hardships in Darfur? Could it impede the recently begun peace negotiations between the government and the Darfur rebel group, the Justice and Equality Movement, in Doha?” Ocampo’s response was “No. For people in Darfur, nothing could be worse. We need negotiations, but if Bashir is indicted, he is not the person to negotiate with.” Immediately following the ICC indictment, JEM, who signed a preliminary accord with Khartoum in February 2009, issued a statement announcing that it rejects negotiating with the government of Al-Bashir.

Ocampo’s enthusiasm to indict Al-Bashir with genocide – in absence of concrete evidence – threatened to destabilize the entire region of East Africa. Ocampo insisted that seeking retributive justice had great importance for Darfuri and Sudanese people, more so than seeking peace. This being the case, the chief prosecutor of the ICC will be perceived as committing political and legal suicide. Politically, half of the countries that first ratified the Rome Statute establishing the ICC in 1998 were African countries; now those same countries are more skeptical about double standards and fairness within the ICC. Legally, the ICC prosecutor failed to build a persuasive case for trial to arrest a sitting head of state with genocidal acts. The arrest warrant of Al-Bashir, rather than protecting innocent civilians, will possibly increasingly risk security and intensify distress in Darfur.

Recent history has taught us that neither humanitarian nor militaristic intervention may “save” innocent civilians, exemplified by Bosnia, Kosovo, Rwanda, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Central African Republic. Consequently, the contemporary policy debate suggests that we ought to think to employ a different framework that deviates from the “responsibility to protect” and “boots on the ground” interventionist approaches in order to put an end to the atrocity in Darfur and elsewhere.

The ICC indictment is not a useful mechanism to be used to solve the Darfur conflict and avert heartless outcomes. It has been perceived as a double standard that applies only towards nations of the Global South and particularly African countries, only contributing to even greater political instability and eventually more violence. The most pressing need is for political pressure on the Sudanese regime to pursue the path of political solution and reconciliation by guaranteeing fundamental human rights, democratization, equitable and sustainable natural resource sharing between the center and the peripheries. These political actions might be what the people of Darfur and Sudan need most as they attempt to steer clear of continuing political atrocities and liberate themselves from a ruthless dictatorship.