Authored by the California Community Partnerships Team at the Othering and Belonging Institute

For inquiries, contact Nicole Montojo at nmontojo@berkeley.edu

Introduction

How the nation responds to Covid-19 and its myriad repercussions will likely have effects that last for decades to come. The unprecedented pausing of our economy and government-imposed shelter-in-place orders require that millions of Americans forgo their incomes, generating a crisis for millions of people as bills, rent, and mortgage payments come due. While some resort to savings to cover their fixed costs, four out of ten Americans did not have enough savings to cover an unexpected $400 expense prior to this crisis. More than 18 million households — one in six — were already paying more than half of their incomes on housing pre-Covid-19. People of color disproportionately represent low income renters and homeowners, and the workers at risk of losing their incomes due to the pandemic. The Covid-19 crisis threatens to further devastate housing stability and exacerbate public health impacts, particularly for communities of color and low-income communities, by pushing more people into homelessness, unsustainable debt, and unsafe living conditions.

Given the dire conditions of a housing environment already in crisis and the evidence supporting the legality of such a measure, rent and mortgage cancellation is urgently needed to provide relief to millions of households and avoid catastrophic effects on health, safety and well-being. Rent and mortgage cancellation policies are being debated in various cities and states, and at the federal level Representative Ilhan Omar has sponsored HR 6515, the Rent and Mortgage Cancellation Act. Such policies are a logical complement to shelter-in-place policies, so that people can continue to protect public health by heeding the law without putting their housing at risk. A recent public opinion poll found that 74 percent of likely California voters, including 69 percent of Republicans, support a policy to “suspend and forgive rents.”1

At pivotal moments of crisis in US history, federal and state governments have intervened and committed billions of dollars to stabilize the housing market through the creation of new programs and policies. These interventions have disproportionately benefited white single-family homeowners and housing corporations, while support for low-income renters and homeowners of color has consistently been constricted.2 Supreme Court rulings and legal arguments point to the ability of local governments to suspend rents (see Legal Precedents section). At the statewide level, regulatory powers, including those reaching private property and land-use decisions, are expanded in times of emergency. Therefore, an amendment to the California governor’s emergency declaration executive order to enact rent and mortgage cancellation statewide is necessary, in addition to passing federal legislation to protect tenants and homeowners. These actions can keep people housed through the current crisis, and serve as a stepping stone toward systemic changes that create permanent stability, affordability, and equity in the long term.

This brief contains:

-

An analysis of the current housing and economic conditions related to the pandemic

-

Proposed principles for designing policy to cancel rents and mortgage payments

-

A review of legal arguments in support of rent and mortgage cancellation

The Necessity of Rent Cancellation

Before Covid-19, California was already in an unsustainable housing crisis. Census data shows that 55 percent of renting households in California were rent burdened, meaning they pay 30 percent or more of their income on rent.3 Low-income, Black, Latinx, Native American, and female renters are more likely to be rent-burdened across the state, according to the Bay Area Equity Atlas’ analysis. In 2018, Pew reported that nationwide two-thirds of rent burdened households have less than $400 cash at their disposal and half “had less than $10 in savings across various liquid accounts.”4 This level of financial insecurity coupled with rent burdened status demonstrates that before the Covid-19 outbreak, California was already in an unsustainable crisis environment when it came to housing. With this level of financial precarity, any short-term disruption to income would mean that many California households would not be able to continue making rent payments.

The Covid-19 outbreak caused a sustained disruption to income, and many people who do not have the means to withstand an extended period of time out of work are having to contend with indefinite unemployment due to the mandated shelter-in-place order. According to estimates by the Economic Roundtable, 62 percent of workers who make 200 percent or below of the federal poverty line are at high risk of unemployment due to stay-at-home measures, demonstrating that those who were already the most economically vulnerable among us are being strained even further by the alterations to the economy Covid-19 has forced.5

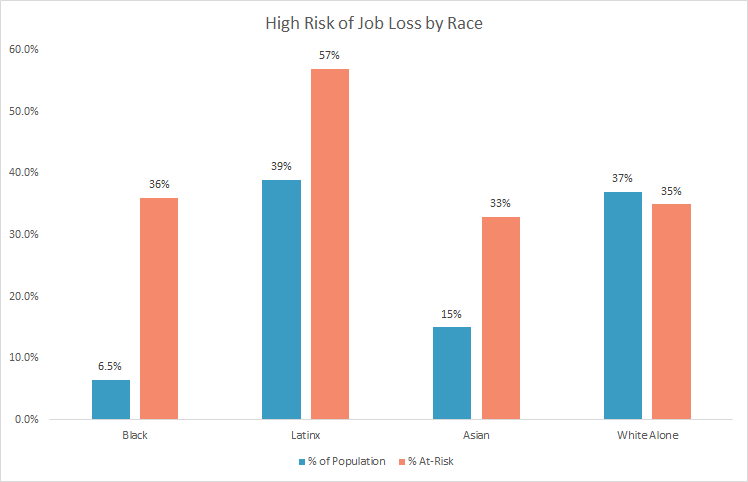

Analysis of those at risk of losing their jobs during this crisis also reflects racial inequities, with people of color at disproportionately higher risk (Figure 1).

Figure 1: High Risk of Job Loss by Race

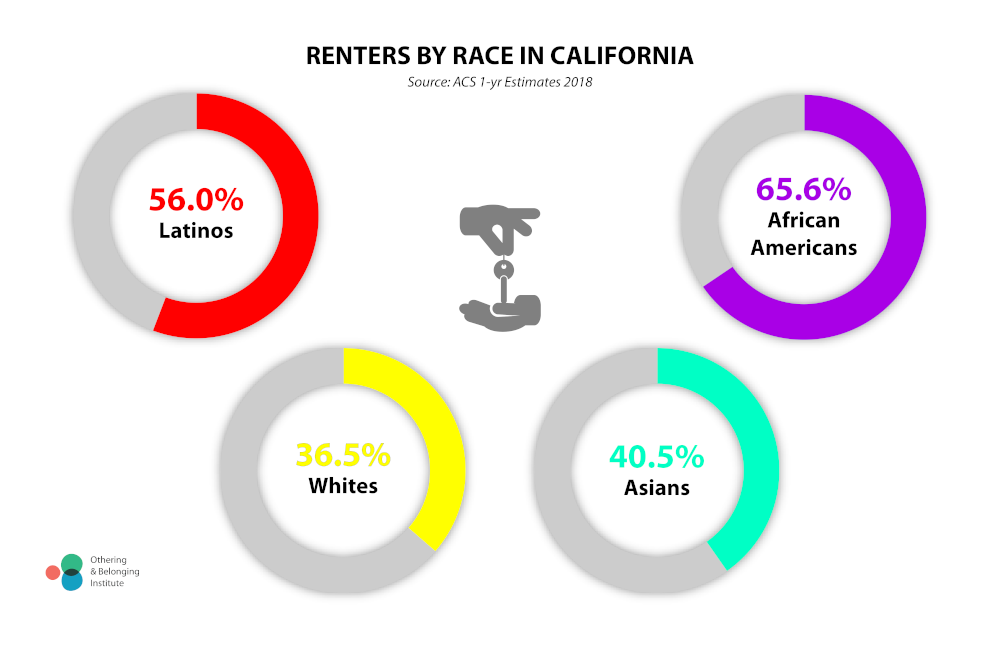

Source: At-Risk of Unemployment – Economic Roundtable; Population Percentages – US Census 2019 Population Estimates.The percentage of renters by race is also disproportionate, with the majority of Blacks and Latinxs renting (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The majority of Blacks and Latinxs are renters in CA

Infographic by Samir Gambhir of the Othering and Belonging Institute

These economic and racial inequities should not be exacerbated because policymakers fail to act and stabilize housing for those who can no longer afford rent.

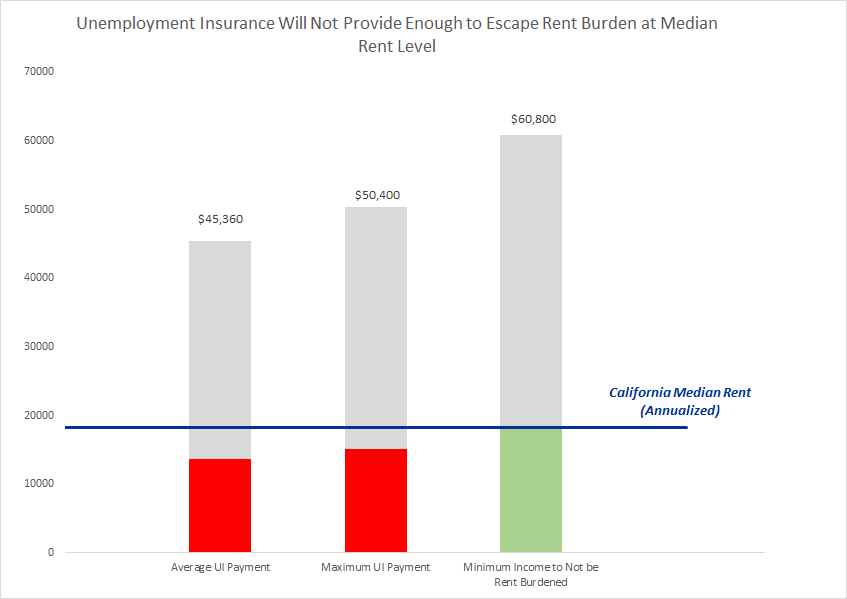

Unemployment Insurance Will Not Provide Enough Protection

As of April 18, there were 19 million people on unemployment insurance nationally, over 17 million more than the same time last year.6 The Center for Business and Policy Research further projects that this number will hit 3.9 million jobs lost by May.7 California is struggling to process the surge in unemployment claims and make payments, which means households are at risk of going for an extended amount of time without any source of income.8 Additionally, unemployment insurance (UI) is not enough to provide people with a rent unburdened level of income – even once the federal supplement is included (Figure 3). Lastly, millions of workers do not qualify for unemployment insurance due to their immigration status or informal employment.

Figure 3: Despite Unemployment Insurance, most CA households will still be rent-burdened given CA median rent is $1,5209

The vulnerabilities created by the current crisis combined with the fact that the tools that have been deployed thus far are not robust enough to prevent unnecessary housing insecurity make a compelling case for implementing rent cancellation as a policy measure. Moreover, the legal authority exists to enact such a provision.

Current Rent and Mortgage Cancellation Legislation and Organizing

Several national member-based grassroots nonprofits and progressive policy research groups, led by People’s Action and Center for Popular Democracy, have designed a federal bill sponsored by Congresswoman Ilhan Omar (D-Minnesota) to cancel rents and mortgages. The Rent and Mortgage Cancellation Act, HR 6515, builds on momentum from a petition signed by over 400,000 people led by ParentsTogether and would cancel rent and mortgage payments for everyone regardless of income or immigration status in the United States. The campaign hopes to pass this bill as part of the next stimulus package, which will require Congress to appropriate funds to cover funds established. For example, HR 6515 establishes a federal fund, managed by HUD, to relieve lost income for property owners and lenders, with zero accumulation or negative impact on credit ratings for tenants or homeowners. This would allow landlords to continue to cover their costs like property taxes and ensure lenders remain solvent. To access the relief, owners must not raise rent for five years and must follow just cause eviction and anti-discrimination protections. It would begin retroactively on April 1 and would last through one calendar month after the end of the declared national state of emergency. Additionally, should the economic fallout of the pandemic cause widespread foreclosures, the bill provides funding for nonprofits, local governments, housing cooperatives, and others to support their acquisition of housing, in an effort to keep units affordable and limit corporate landlord growth.

While many local and state housing rights groups have signed on to the national campaign and helped design Rep. Omar’s bill, they are also pushing for state and local action in states including New York, New Jersey, and California. In California, local and statewide grassroots organizations like Tenants Together, in coordination with the national Right to the City Alliance, directed a week of action to flood Governor Gavin Newsom’s office with calls and messages urging him to cancel rent, mortgage, and utility payments. Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) is also supporting municipalities to enact rent and mortgage cancellations.

Policy Design Principles

It is the government’s responsibility to protect public health and safety by ensuring we can all shelter-in-place and fully recover from this crisis. A state or federal rent and mortgage cancellation policy must be designed to ensure that everyone, but especially those who are most economically vulnerable, can stay safely housed throughout the crisis, recovery period, and beyond. This means prioritizing renters, people living paycheck to paycheck, workers who have lost their jobs or ability to work, and anyone experiencing illness (whether directly or in their household).

Just as the health impacts of the pandemic are racially disproportionate,10 the economic burden and financial impacts of the pandemic are not being shared equally either. Given these disparities, the government response must equitably target public resources while ensuring that no one is left behind. The following are principles that should guide efforts to design a policy response that achieves this.

Prioritize people’s access to stable housing first.

Any housing payment relief measures must adequately respond to the scale of immediate need among both renters and homeowners. Temporary eviction moratoriums and suspensions of rent and mortgage payments are a step in the right direction, but alone they simply delay the crisis instead of providing real relief. To ensure that people can actually get back on their feet after shelter-in-place and truly thrive beyond the recovery period, we need a full cancellation of rent and mortgage payments until each household is able to secure income again.

-

Cover primary residences, not secondary or investment properties: Priority should be placed on safeguarding access to stable housing now and through the recovery period. The Rent and Mortgage Cancellation Act (HR 6515) achieves this by extending rent and mortgage cancellation only to homes that people live in. The means a cancellation of all rental payments, and only for mortgages on owner-occupied, primary residences, but not vacation homes/rentals, investment properties, or other housing under corporate ownership.

-

Provide additional coverage to preserve affordable housing: To preserve existing affordable housing, mortgage cancellation could be extended beyond owner-occupied homes to also apply to housing with affordability deed-restrictions. PolicyLink recommends that after owner-occupied homes, mortgage cancellation is prioritized for nonprofit affordable housing, Project-Based Section 8, HUD housing, LIHTC, and small landlords, with the requirement that affordable housing providers that receive this benefit cancel rent and provide automatic lease renewal.11

Design targeted approaches to achieve universal housing stability

To ensure that the most vulnerable among us are able to stay in their homes, full cancellation of rent and mortgage payments on primary residences must be granted to anyone who does not have income sufficient to cover housing costs. This approach accounts for the particular needs of people unable to work because of illness, shelter-in-place orders, parents taking care of children whose schools are closed, unsafe labor conditions, lack of health insurance, or lost hours or being laid off as a result of the economic effects of the pandemic.

-

Accommodate accessibility needs: The process for obtaining relief should be as accessible and streamlined as possible, taking into account different accessibility needs, particularly for seniors, people with disabilities, and people with language access needs.

-

Minimize barriers: The policy should not create barriers that exclude people in need from relief. HR 6515 successfully avoids potential barriers and administrative burdens by not requiring documentation of immigration status or a formal lease to be eligible. To minimize barriers as much as possible, the bill authorizes universal rent and mortgage cancellation, which as previously noted, would begin retroactively on April 1 and would last through one calendar month after the end of the declared national state of emergency. Alternatively, a phased approach that includes a combination of targeted and universal strategies could balance the need to direct government resources to populations that are most economically vulnerable ― who are more likely to be renters ― with the goal of ensuring no one in need is left behind. This sort of approach could include, for example, two phases: an initial time-limited phase (such as the period defined in HR 6515) of universal rent cancellation along with mortgage cancellation for essential workers and households unable to pay, followed by a second phase during which households which are still unable to make rent or mortgage payments can receive extended rent or mortgage cancellation.

-

Include essential workers: Consistent with a targeted framework, essential workers should be included for relief under any rent or mortgage cancellation program. Jobs categorized under the essential work category, although they keep the economy and society functioning, are often low paying positions. This means that many essential workers have low incomes, have low levels of wealth, and were already in precarious housing situations prior to the pandemic. This group also largely consists of women and people of color. Even though this category of workers is still employed, their situatedness to the universal goal of housing stability for everyone means that the additional support from rent or mortgage cancellation targeted to this group makes the universal goal more achievable. Traditional universal policy designs usually increase existing disparities by providing assistance equally across groups who are in need as well as those who are well off. This targeted approach is a step toward closing the gap. Additionally, essential workers are undercompensated for the outsize work they do to keep the economy stable both in relatively stable periods as well as through this crisis. Providing this group access to a rent and mortgage cancellation policy through the duration of the measure’s existence helps move their compensation closer to their level of contribution and is justifiable on fairness grounds given their role in this current moment.

Ensure that racial wealth disparities are not exacerbated by policy design.

Because the US housing market is at its foundation a racialized system, policy interventions run the risk of deepening racial inequities. Universal solutions generally perpetuate existing inequalities because they do not take into account the particular needs and differentials of groups across the population. With regard to rent cancellation, a number of measures can work toward reducing the potential for exacerbating racial disparities. A rent cancellation policy can be structured such that as segments of the economy begin to reopen, those who continue to not have a source of income are still protected. HR 6515, drafted to provide retroactive relief to April 1, 2020, can prioritize retroactive payments to employees in the most at-risk sectors. Additionally, the bill’s provision establishing an acquisition fund that prioritizes nonprofits and public housing agencies in acquiring housing that comes up for sale during the economic downturn should contribute to housing stabilization for vulnerable communities. Proposals such as these are targeted policy options that can reduce the chance of exacerbating racial and economic inequality.

-

Provide equitable funding to stabilize small landlords, mortgage holders and affordable housing: A public fund can offset the burden of lost rental revenue to property owners. HR 6515 establishes a fund that would provide aid to cover income loss for owners and investors as long as they meet certain stabilization and non-discrimination requirements. Targeting funding to owners whose total property holdings can be considered a modest investment (eg under $3 million total in assessed value) could ensure that limited public resources prioritize owners whose assets comprise a personal investment and/or a modest income stream. While the HR 6515 Landlord Relief Fund does not restrict eligibility based on assessed value, it does establish a tiered priority system for payments from the fund based on assets, revenues, disclosure requirements, and profit status of lessors, giving priority to “nonprofit organizations or entities and lessors having the fewest available amount of assets” (Section 4e).

-

Establish an equitable revenue source: The burden of missed housing payments under current arrangements are falling entirely on tenants and homeowners, who in many cases are the least able to cover these costs. If the costs of rent cancellation are absorbed into existing tax structures or mitigated through budget cuts and austerity programs, this will exacerbate the already extremely unequal distribution of wealth in California and the United States. To provide funding that stabilizes small property holders and renters, a progressive wealth tax could be established that calls on high-wealth households and companies to pay their fair share in stabilizing housing for everyone. A wealth tax generates funding for this program by sourcing revenue from those who are most able to pay. The proposal from Godsil and Ronen suggests a “mansion tax” that applies to high value homes for the duration of the crisis.

Establish strong education and enforcement measures to ensure effective implementation

Creating universal access to rent and mortgage cancellation benefits requires that every tenant and homeowner knows their rights, and that every landlord understands their responsibility under the new policy. Implementation efforts must therefore include extensive public outreach and education efforts that ensure information on the policy reaches all communities.

-

Fund education and outreach: HR 6515 would require HUD to notify tenants and mortgagors of the cancellations enacted by the bill (Section 2c), but additional measures could be taken to ensure that the policy works as intended. For example, funding could be allocated for a small grants program for community-based nonprofits and legal aid organizations to run targeted outreach and assistance programs.

-

Include enforcement mechanisms: As demonstrated by widely reported illegal evictions occurring in states where eviction moratoriums have already been enacted, simply passing protection measures is not enough. HR 6515 establishes a right to legal action for anyone wrongfully denied rent or mortgage cancellation according to the policy, as well as penalties for landlords or lenders that take adverse action against someone who exercises their rights under the bill (Section 3).

-

Mitigate unintended consequences: If rent cancellation is established, tenants who exercise their rights could face retaliation, such as harassment or neglect of habitability issues, in an attempt to force them from their homes. To preemptively address this, PolicyLink recommends expanding access to quality and safe emergency housing for anyone forced from their home due to retaliation, which would also provide shelter for unhoused people, people released from detention, and anyone facing any sort of threat to safety, from habitability problems to domestic violence.12

Create systemic changes toward permanent stability and affordability

The current situation lays bare deep systemic inequities built into the existing housing market. While the pandemic has exacerbated these problems, many within our communities have long struggled to access safe, stable, and affordable housing in a profit-driven market. A rent and mortgage cancellation policy can be designed to do more than address the immediate emergency; it can be a significant step in transitioning to a more just and equitable housing system that benefits society as whole.

Proposals like HR 6515, which conditions landlords’ and lenders’ access to relief funds on their commitment to fair renting and lending practices, affirmatively furthers fair housing goals. The bill’s Affordable Housing Acquisition Fund creates an opening to reimagine and resource shared ownership and permanent affordability by allowing nonprofit developers, cooperatives, community land trusts, and government agencies the first opportunity to purchase rental properties from private owners that opt to sell. At local levels, this mirrors community or tenant opportunity to purchase acts or California’s Surplus Land Act, and further enables the use of such policies by providing federal funding to acquire properties under these policies.

The question of “who pays” for a rent and mortgage cancellation can also point towards a more equitable tax structure. The current tax system includes hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies and expenditures designed to support wealth building, particularly around homeownership, with the vast majority of this going to high-wealth households.13 By shifting tax structures, the costs of a cancellation policy could be shouldered more equitably across income and wealth groups. Finally, at multiple points in US history, crises have required the innovation of programs that Americans continue to rely on: Social Security, unemployment insurance, Medicare, and others. Rent and mortgage cancellation can provide the framework for an ongoing program to support people in times of crisis. From tornadoes in Tennessee to fires in California, we will continue to face unexpected crises. Through the establishment of an ongoing program, renters and homeowners can be supported on an individual basis during these times of crisis in order to accelerate recovery and protect public health.

Legal Context

Since the government’s rightful action to slow the spread of the virus caused current economic hardship, the government also has the responsibility to ensure that people have enough economic support to survive the mandated orders and maintain a stable foothold in their communities. Policymakers should abide by this principle and have the legal authority to do so.

The Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment first appears to be a roadblock to implementing a rent cancellation.14 However, Nadia Aziz and Michael Trujillo of the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley argue that the authority to cancel rent exists under a jurisdiction’s expanded police power – or general regulatory power – during an emergency.15 In a state of emergency, police powers provide for the use of real property, price controls including rent, and can regulate the landlord-tenant relationship even though it is considered private. Therefore police powers can allow for the restriction of property rights in the name of public health or when a threat to safety or welfare exists.16

In support of this argument they cite the 1976 California Supreme Court ruling in Birkenfeld v. City of Berkeley, arguing that “the broad authority of the police power likewise extends to local governmental authority to enact price controls, including on rent, provided the legislation is "reasonably related to the accomplishment of a legitimate governmental purpose."17 This position is also backed by University of the Pacific McGeorge School of Law professor John Spranking’s reasoning that the courts “have long recognized that emergencies allow for exemptions to constitutional protections afforded under the Fifth Amendment.”18 This position is additionally supported by the US Supreme Court case Levy Leasing Co. v. Siegel which found that “constitutional protections for property owners may be suspended where there is a crisis "so grave that it constituted a serious menace to the health, morality, comfort, and even to the peace of a large part of the people of the state."19 Furthermore, in the case Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, the Supreme Court held that when land use is regulated and not actually taken possession of, the regulation does not automatically constitute a taking but is balanced against the public purpose it serves.20 Given the extraordinary health and economic crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the temporary cancellation of rent to provide relief for those adversely affected by the quarantine order as a public health necessity would not constitute a taking requiring compensation as evaluated by the Penn Central balancing test.

Although police powers reside with the states and not with the federal government, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) fund Rep. Omar’s bill establishes means that compensation for altered use of property is provided. Even if the regulation of property is determined to be a taking, the compensation required to accompany a taking is accounted for in this legislation. Moreover, the precedents mentioned above outline state and even local authority to act in the absence of action from the federal government.

For California, Aziz and Trujillo also point out that the Costa-Hawkins Act of 1995 shouldn’t pose any barriers to enacting a rent cancellation because the act protects a landlord’s ability to increase rent after a vacancy. The suspension of rent does not take this protection away, it simply delays the protection to a later time.21 Furthermore, with eviction suspensions in place, Costa-Hawkins should not matter since landlords can only set rents at the market rate after a vacancy. "In the context of this international public health emergency," Aziz and Trujillo argue, "the delay in exercising the right to collect rent this regulation would impose is permissible under state law."22

Conclusion

Lack of action to cancel rents and mortgage payments raises the risk that the pandemic response results in exacerbated housing instability, homelessness, debt, and racial inequities. The shelter-in-place orders have been a crucial measure to flatten the curve of Covid-19 rates, but people’s shelter must be stabilized as well. Millions of people have lost income and don’t have savings, putting their housing at risk. In such an emergency situation, it is the proper role of government to take action to protect public health. A principled and effective rent and mortgage cancellation policy will prioritize people's access to stable housing first, utilize targeted approaches to achieve universal housing stability, and reverse racial inequities in wealth and housing. It must include strong implementation, public education, and enforcement mechanisms, and be designed to lead to a more permanently affordable, stable, and equitable housing system.

- 1Data for Progress (4/27/20) “California Housing Precarity in the Context of the Coronavirus Pandemic.” https://www.dataforprogress.org/memos/ca-housing-precarity-coronavirus

- 2While the Federal government has never enacted a rent or mortgage cancellation, there are numerous precedents for subsidization of housing costs that today appear as natural rights or basic financial technologies. While the Federal government has never enacted a rent or mortgage cancellation, there are numerous precedents for subsidization of housing costs that today appear as natural rights or basic financial technologies. For example, homeowners have long benefited from the ability to write off mortgage interest payments on their taxes, which in 2014, was calculated at a subsidy of $93.1 billion. In California, a state-level renter subsidy will get a renter between $60-$120 in subsidy. At the federal level, the HUD budget which is the primary support for low-income renters, has consistently decreased since its 1965 founding, and has seen renewed cuts in 2020. During the Great Depression, with more than half of US homes in foreclosure, the federal government created the Home Owners Loan Corporation with $3 billion put towards one million homes in foreclosure or at risk of foreclosure. This represented a direct public investment rather than a cancellation of payments. With the passage of COVID-19 economic packages, funds could be allocated similarly. In 1934, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) was created to insure loans, particularly lower down payment long-term self-amortizing loans. At the time, the building trades was the largest source of unemployment in the country. The goal was to stimulate new housing creation by bringing lenders to the table who were still scared due to the economic crisis. The FHA – which has insured over 34 million mortgages since 1934 and underwrote $120 billion dollars in new housing by 1962 – provides a precedent of the federal government intervening in the private housing market by investing significant resources to house people, stabilize the economy, and stimulate jobs. At the same time, its essential to acknowledge that less than 2% of that support went to Black people, Indigenous people or people of color.

- 3US Census, Table DP04, Selected Housing Characteristics for California. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=California%20Housing&g=0400000US…

- 4Erin Currier et al., American Families Face a Growing Rent Burden: High Housing Costs Threaten Financial Security and Put Homeownership out of Reach for Many (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2018), 5, accessed April 17, 2020, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/04/rent-burden_report_v2…

- 5 Daniel Flaming and Patrick Burns, In Harm’s Way: California Workers at High Risk of Unemployment in the COVID-19 Pandemic (Los Angeles, CA: The Economic Roundtable, 2020), accessed April 21, 2020, https://economicrt.org/publication/in-harms-way/ The Economic Roundtable used ACS, Department of Labor, and Federal Reserve data to identify job loss risk factors.

- 6United States Department of Labor, “News Release: Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims,” April 30, 2020, https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf

- 7George Avalos, “Bay Area coronavirus job losses will top 800,000: California Faces Nearly 4 Million in Job Losses by May, Study Says,” Mercury News, April 8, 2020, https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/04/08/bay-area-coronavirus-job-will-80…

- 8Supra Note 4.

- 9 Sources: American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates 2018 for California, Table DP04. Rent burden is calculated as annual rent expenses equaling 30% of annual income. Sarah Bohn, Marisol Cuellar Mejia, Julien LaFortune, “Unemployment Benefits in the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Public Policy Institute of California, April 9, 2020. The maximum weekly benefit in California, with the federal supplement of $600 included, is $1,050. The average UI amount that applicants receive in California is $945 a week once the federal amount is added. This translates to annualized rates of $50,400 and $45,360 respectively. Both fall below the threshold of $60,800 that a household would need to make to be able to pay California’s median rent without being rent burdened.

- 10Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Cases in the US,” April 29, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

- 11PolicyLink, “Cancel Rent, Reclaim Our Homes,” https://ourhomesourhealth.org/cancel-rent-reclaim-homes, accessed April 30, 2020

- 12Ibid.

- 13Ezra Levin, Jeremie Greer and Ida Rademacher, “From Upside Down to Right-Side Up: Redeploying $540 Billion in Federal Spending to Help all Families Save, Invest and Build Wealth,” CFED: https://prosperitynow.org/sites/default/files/resources/Upside_Down_to_…, accessed April 30, 2020

- 14Grace Hase, ”San Jose Rent Suspension Proposal Ruled out over Constitutional Concerns,” San Jose Inside, April 9, 2020, https://www.sanjoseinside.com/2020/04/09/san-jose-rent-suspension-propo…

- 15Ibid.

- 16Nadia Aziz and Michael Trujillo, “Rent Suspension – Letter of Support,” to San Jose Municipal Government, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/577c8338bebafbe36dfc1691/t/5e8cf…

- 17Ibid., citing Birkenfeld v. City of Berkeley 17 Cal. 3d 129, 158 (1976)

- 18Jacob Woocher, “An Eviction Moratorium Is Not Enough—Suspend Rent,” ShelterForce, March 23, 2020, https://shelterforce.org/2020/03/23/an-eviction-moratorium-is-not-enoug…

- 19Ibid.

- 20Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104, 124 (1978)

- 21Supra Note 12.

- 22Ibid.