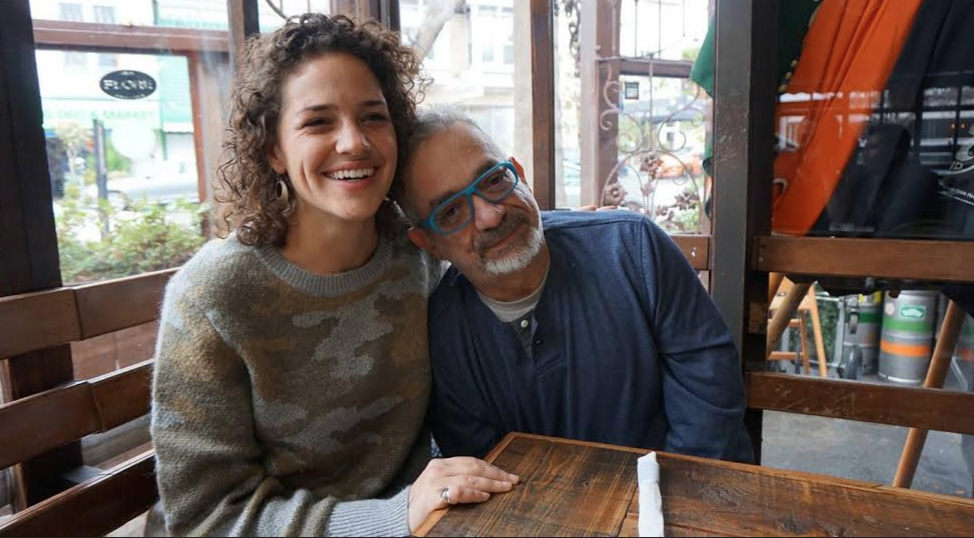

Haas Institute researcher Nadia Barhoum interviewed Lebanese-American painter and award winning writer Rabih Alameddine. Alameddine has authored four novels and a collection of short stories. Listen to the audio of their discussion here.

Haas Institute researcher Nadia Barhoum interviewed Lebanese-American painter and award winning writer Rabih Alameddine. Alameddine has authored four novels and a collection of short stories. Listen to the audio of their discussion here.

Transcript:

[Nadia Barhoum]: I know you started publishing later in your life, so I wanted to hear more about your path to becoming a writer and how.

I've told this story so many times, so it becomes a story more than a reality in some ways. Let's see. I've always wanted to be a writer. When I was four, my father asked me what I wanted to do with my life and I said I wanted to be a writer. Of course at the time, writing was Superman and Batman comics. But I did it for a long time, which I think is great... How I started writing was being frustrated with reading books that did not reflect my experience particularly being an Arab and a gay man during the AIDS crisis.

I want to understand more about how you grapple living between two worlds of the Arab and West and how you're able to navigate those differences.

I remember when I first came to the US [to UCLA] and I was 17. I was taken in by a group of Lebanese friends. We did everything together, that it got to a point I had no American friends. I was not involved in American culture to speak of, even though I lived here. When I applied for grad school, I came here and for a while I didn't have any Lebanese friends and it was primarily to see what it would be like to be an American.

But somewhere along the line, the two integrated—and I don't mean that I did not become an American, or I did not become Lebanese. The dichotomy left, because I became sort of my own person. I no longer cared to listen to this or to listen to that. I still think it's really important when there is a part that collates and at that time specifically, when I wrote in Lebanon, I belonged. In America, I fit but do not belong. But in Lebanon I belong, but I do not fit.

I still feel that way in some ways because I’m neither here nor there, but I'm both here and there. But for me that's how I integrated. I don't know how it's done for other people. But I don't particularly care what one culture says is okay and what culture says is not okay. I am my own culture.

There are so many stereotypes that we must fight against, as Arabs are the ultimate “Other” right now in this country. And because of that, I'm wondering how you're trying to challenge those stereotypes?

I don't think I consciously try to challenge stereotypes. My existence is a challenge to stereotypes. I don't consider myself a political writer. I don't sit down to write something politically or to challenge stereotypes. Being who I am, almost everything I do will be political, almost everything I do will be a challenge to those stereotypes. So, in having a conscious decision to do something like that becomes an interference in the story. For me, the story is paramount. But I don't think I've written a story that did not challenge stereotypes. It's almost a circular thing.

An Unnecessary Woman feels like it wasn't written by a man. I want to know how you were able to authentically represent and be the voice of a woman.

It was not written by a man. It was written by me. I mean the trouble is that we think of the separation—of, “this is a man and this is a woman.” That kind of dichotomy for me never really existed. I did not write a book about a woman. I wrote a book about Aaliya. So this book is Rabih writing about Aaliya. It's not a man writing about a woman. I do not represent all men. Aaliya does not represent all women. It’s just a single person writing about another single person. My whole object of writing in a character is making her real. I do not sit down and think, "Oh, how can I make this character real as a woman?" No. I sit down to think, “How can I make Aaliya real, come to life? So, that's how it's done. I don't know how a man would do such a thing. I know how I would do such a thing, and that's a big difference.

[Ramzi Salti]: Something I was asked to ask you by several people, especially from young men living in the Middle East—if Rabih Alameddine was able to live in America as an openly gay man, that gives them hope that they can do the same. How do you feel when you hear such statements?

It makes me uncomfortable. I can't even begin to imagine that I'm an example to somebody, but I also don't think it's about me being gay in America. I was gay in Lebanon. (Actually, I sometimes joke that I'm not gay, I'm grumpy.) But it's not that I am something here and something else there—I am what I am. That I’m an inspiration for somebody—that is beyond me. Really, I have issues. I never leave the house. I'm at home most of the time. I can't find a date. All that lovely stuff. So anybody who looks up to me is, I think, you really need to go out more. And this is not modesty. Like everybody, I have my issues and I of course think that mine are a lot more troublesome than most other people, and I envy most people.

[Nadia Barhoum]: When I read your books, it does give me a sense of belonging that…

Which is funny because I don't belong!

But because you don't belong, doesn't that create belonging for us?

Maybe. Again, I don't know how a reader would experience my books because I'm not reading them. So I really don't know. But again, I have issues with belonging and not fitting in and being the outsider all the time. Anybody who finds inspiration from that, I find strange. What is interesting is that I don't have that relationship with any writer. I have many writers that I admire, and I think very highly of them. But I don't get inspired in the same way by them.

You grew up in the Arab world and you live here now in the US, but you choose to write in English. I just want to know what your relationship to language is?

I choose to write in English because it is the only language that I can write in. I do speak Arabic and I do write it, but as you probably know, the Arabic education in Lebanon is horrific. We don't care to teach Arabic in Lebanon. I watch my nephew and niece [in Lebanon]—they're not allowed to speak Arabic in school, they're supposed to speak French, because that's the mark of sophistication. It’s a remnant from colonial times in our part of the world, and I don’t think that Lebanon, or any other place, actually wishes colonialism to come back. So no, I was taught Arabic, but I was taught mediocre Arabic.

Which of your books have been translated into Arabic?

The one that was just banned!

Please tell us a little bit about that.

My first book Koolaids was bought by a publishing house and was translated really badly and it never came out because the translator refused to put his name on the book. He was so terrified, and they wanted me to cut out any reference to Syria. So I refused and it never came out. And then Hakawati was bought, and I got an email from the publishing house that was in Dubai and (because apparently they bought it without reading it), it said, “The translator said that the book has sex. We can not do this. The writer will understand.” So finally I, the Divine was translated and I think that’s my least controversial book. Although you know, I had one publisher say that it was the most insidiously controversial book, and I agree with that. But it was just banned in Kuwait. Yay!

You were sort of gloating about that (on social media) but don't you think in a way it is tragic all these readers will…

Of course it's tragic! But also, I grew up in Lebanon and whenever something got banned, believe me, we could get it. The trouble is it won't be in bookstores so people won't even know about it. But I think whenever there is censorship, one must get censored, otherwise you’re just diddling around. One of the biggest issues in our part of the world is censorship. So to be censored means that I am doing something that is right, and that's a big deal.

I think achieving comedy in writing is one of the most difficult tasks possible. And yet, I found myself laughing throughout Koolaids despite all the tragedy and suffering, you still find yourself laughing out loud. Is that something you're trying to do or are you unintentionally funny?

No. One does not try to be funny, because if you try, you fail. No, I don't try to be funny. See there's something in Arabic that we don't have in English which is, what we say, khafeef al dam and that is a big deal for me because the opposite is thaqeel al dam, and that in writing is unbearable.

I know a lot of writers that are well respected that I cannot read because they're very serious, but at the same time they’re thaqeel al dam—they are unbearable. Like, please! My first response is always, “Get an enema, you know, just get over it.” So let's just say I write as if I've just had an enema. It's not about being funny, although it will come out sometimes as being funny, but it’s about being light. And I don't mean light as in airy fairy. In the bleakest time, in the worst times possible, the only thing that makes us human is the ability to make fun of it.

If you hadn’t read “____” book, you wouldn’t have become a writer.

V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas. What was important was that it was the first time I read a book about, for a lack of a better world, brown people. Like me. That we, from the third world, could be the main protagonists of a novel. So Naipaul, and why I will always love him, even though he is a big jerk, is that he is an amazing writer. What was truly outstanding for someone like me is he basically said that my story is important enough just like an American's or a white Englishman's or just like a Frenchman's. We could be the protagonists of a novel by Balzac. And Naguib Mahfouz did the same thing later... For me, the first time was when I was sixteen and it was Naipaul. We are important enough and that was a big deal for me.

Koolaids was like that for me. It was the first time I picked up a book and said “Wow, this is the book I have been waiting to read my whole life” and I think it's so important to have someone like you...your writing has been transformative in so many ways. In a time when our narratives have been so co-opted and marginalized, it's just so refreshing and important to have your work out there for us.

Thank you. My response for that is: Don't read my work, go out there and make your own narratives.