dog_whistle_politics_cover.pngIan Haney-Lopez addresses the connection between dog whistle politics and the increasingly successful right-wing attacks on the government and unions, and offers a frame for the labor movement to mobilize and defeat dog whistling.

Executive Summary

Unions must mobilize to defeat racism because it destroys solidarity and brutalizes union members, because the demographics of working people are changing rapidly, and because morality demands action. But mobilizing all of labor to join the fight against racism will not be easy: race fractures the labor movement itself. AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka said of Ferguson, Missouri, “our brother killed our sister’s son,” and in doing so, he spoke to the tragic facts, and also to the internecine racial fault lines that shatter worker solidarity.

For unions to recover, they must both fight the injustices done to people of color and simultaneously emphasize the common interests that all workers share. César Chávez knew this when he built a farmworker coalition across race lines, uniting Filipinos and Mexicans in California’s fields. Martin Luther King Jr. embodied this in joining the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis and in organizing the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington. Seeking to build a bridge between labor and the civil rights movement, King said to the AFL-CIO in 1961, “Our needs are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community.”

A shared commitment to challenging racial and economic injustice depends on everyone recognizing that racism is more than prejudice by one individual against another. It has been, and remains, a way to structure society, the economy, and government. Consider slavery—the Southern way of life was built to rationalize this barbarism, the economy depended on it, and government was designed to protect it. Though not to the same extent today, racism nevertheless continues to play this structuring role.

This is most evident in our politics, especially when viewed from the perspective of the last half-century. Fifty years ago, the civil rights movement transformed the place of African Americans and other nonwhites in society, ending formal segregation laws as well as racist restrictions on immigration. In turn, however, these changes contributed to rising anxiety among some made nervous by racial change, and politicians quickly sought to harness and then to foment this seething sense of insecurity

The Republican Party in particular, though eventually many Democrats too, began to campaign by scaring voters. They did so by dog whistling: using coded terms like “inner city crime” and “silent majority” that on the surface did not mention race, but that just underneath coursed with racial power, telling a story of decent whites under threat from dangerous minorities. Today, nobody better symbolizes this toxic politics than Donald Trump.

Yet for all its ugliness, this was strategy, not bigotry. Keeping minorities in their place was never the main point. Instead, the goal was to win elections, and also to satisfy the demands of the billionaires funding political campaigns. This required stoking resentment not only against nonwhites but also against activist government, which was painted as coddling minorities with welfare while refusing to control them through lax criminal laws and weak border enforcement. In effect, powerful elites used the politics of fear and division to hijack government for their own benefit. Pandering to racial anxiety and enflaming hatred against government, they distracted voters from recognizing the threat posed by increasing concentrations of wealth and power.

Today, the richest 0.1% of Americans holds 22% of the country’s wealth—the same share held by the bottom 90% of the population.1 These are levels of wealth inequality not seen in a century. As we slowly emerge from the Great Recession, we find ourselves confronting levels of poverty and economic hardship we thought we had left long in the past, with pensions gone, home equity erased, jobs scarce and little promise for our children. Once again, robber barons rule a rigged system, with government and the marketplace in their pockets. In their greed, they are stifling shared economic prosperity, limiting the mobility of current and future generations, and endangering our democracy.

Purpose This framing paper explains and offers a response to the gravest threat facing the labor movement and indeed our democracy: the power of wealthy elites to use racial scapegoating to turn working people against each other and against good government, allowing them to seize ever more wealth and power while hollowing out the working class.

Audiences This paper simultaneously speaks to two audiences that typically perceive little common ground, or worse, see themselves at odds: those concerned foremost with racial injustice, and those focused first on class inequality. The message for both is the same: progress requires recognizing how race and class intersect.

Goals This framing paper provides:

- A deeper understanding of the violence inflicted on minority communities. From murderous policing to mass incarceration to slashed spending on schools and urban neighborhoods, racial politics more than racial prejudice explains the devastation of barrios and ghettoes. The truth is, politicians and their big money pals play a much bigger role in perpetuating racism than individuals do.

- A basis for worker solidarity. Dog whistle politics makes clear that white workers have a direct stake in combating racism, because stoking racial fear is the sorcery the right uses to win broad support for policies that wreck the working class. Defeating racism’s power to divide us becomes everyone’s agenda, not only a minority concern.

- A way past the race vs. class debate. Some activists insist the most important issue is racism, others that it’s all about class. They’re both correct, because race and class are inseparably intertwined. When politicians use racial dog whistles to defeat working-class solidarity, they demonstrate the fundamental connection between race and class.

- A broader goal for labor. The whole country has lost tremendous ground to divide-and-conquer politics, and now the only way forward is a new social movement demanding that government put people and not corporations first. Labor can best spearhead this new movement that will be years in the making.

The Risk—and Reward— of Talking About Racism

Dog whistle politicians constantly warn that liberal government and unions care more about appeasing minorities than about protecting hardworking whites. This drumbeat makes it risky for labor to mobilize around nonwhite concerns, because it can make conservative accusations ring true to many white workers.

But the solution cannot be to avoid race and to exclusively address class interests. To talk solely about economics leaves racial demagoguery unchallenged, allowing it to continue dividing workers. It also leaves workers of color alienated and angry that the labor movement is ignoring the gross injustices they confront.

The only way forward is to connect race to class, and class to race—by building an inclusive social movement that silences dog whistle politics and demands that government put people first.

Dog Whistle Politics and Worker Power

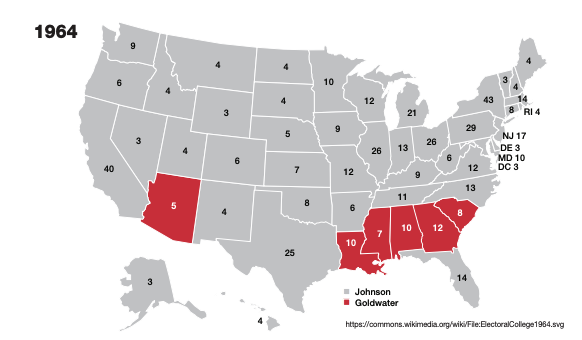

In 1964, on the day he signed the most momentous civil rights act in a century, President Lyndon Johnson confessed to an aide his fear that “we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come.”2 Johnson recognized that the civil rights movement’s success in improving black lives was simultaneously increasing white anxiety, and he expected a significant but temporary political backlash. He failed to anticipate that the GOP would purposefully construct a strategy around covert racial appeals that would last into the present and encompass the whole country.

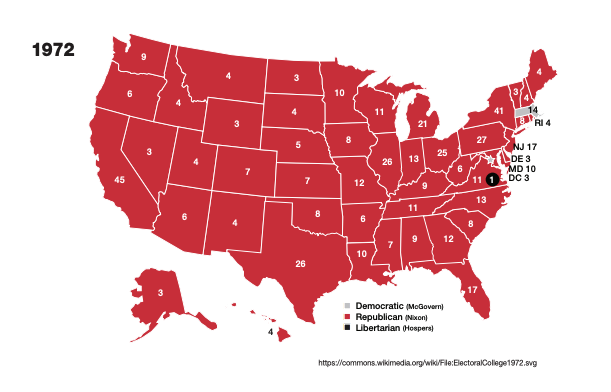

Through 1960, Republicans and Democrats were roughly equally committed to civil rights. In the rising racial insecurity, however, the GOP thought it saw a wedge it could drive with a sledgehammer. The New Deal coalition that kept returning Democrats to power was made up of working-class whites in the North and South, African Americans, and Northeastern liberals. The GOP realized it could use race to shatter that coalition. Coming out of a meeting of the Republican National Committee in 1963, the conservative journalist Barry Goldwater attempted this new attack in 1964, saying “We’re not going to get the Negro vote as a bloc in 1964 or 1968, so we ought to go hunting where the ducks are.” Outside of the Deep South, the tactic failed and LBJ won in a landslide. By the new decade, however, racial panic was more widespread, and Richard Nixon opted to build his 1972 campaign around racism. Using terms like “law and order,” “forced busing” and “the silent majority,” Nixon embraced dog whistle politics. As Nixon’s special counsel, John Ehrlichman, explained: the “subliminal appeal to the anti-black voter was always present in Nixon’s statements and speeches.” That year, Nixon won 70% of the white vote—including the vote of many workingclass, unionized whites. Just eight years after it seemed unassailable, the New Deal coalition had been broken. No Democratic candidate for president has won a majority of the white vote since.

Robert Novak reported: “A good many, perhaps a majority of the party’s leadership, envision substantial political gold to be mined in the racial crisis by becoming in fact, though not in name, the White Man’s Party.”

Demonizing Government

Notwithstanding the energy Nixon poured into scapegoating minorities, stimulating racial hatred was never his main goal. Instead, his agenda was simply to win elections. From other politicians, though, and with the backing of big money conservatives, a new goal soon emerged: use dog whistle tactics to break popular support for government efforts to ensure a strong working class.

Government is essential to a broad and shared prosperity. Laws help protect the rights of working people to speak for themselves; regulations guard against marketplace fraud and abuse; government pays for the public goods like education and infrastructure that provide routes of upward mobility and that boost the whole economy; and the state provides a safety net in times of individual hardship or structural economic dislocation. From the New Deal through the Johnson administration, this version of activist government aimed at helping people was broadly popular.

Yet some among the rich hated these government efforts. More than anything, they loathed the taxes they had to pay to support liberal programs. In addition, they bristled when government regulated their business practices to protect workers, consumers and the environment. For all their anti-government rhetoric, though, the financial titans didn’t desire to actually do away with government: they wanted to control it for themselves. For the super wealthy, government is both an enemy and an opportunity: an enemy to be defeated and an opportunity to be seized, by bringing government’s power and dollars under their sway.

More than Nixon, Ronald Reagan masterfully exploited dog whistle politics to trash good government. There’s a racial story Reagan liked to tell that illustrates his method. Looking out to his overwhelmingly white audiences, Reagan would explain how he sympathized with their frustration when they waited in line to buy hamburger, while “some young fellow” ahead of them used food stamps to buy a T-bone steak. When he first tried out that story, he didn’t say some young fellow buying steak; instead, he said it was a young “buck”— a Southern term for a strong black man. This language was dangerously explicit, and many criticized Reagan for racial pandering. Rather than abandon the story, though, he simply dropped the racial term, leaving the racial imagery clear to his audience: blacks were lazy and larcenous, ripping off society’s generosity without remorse; whites were hard workers who played by the rules, and as a reward were struggling to make ends meet.

Then as now, there was dire need in working-class communities for better jobs, schools, transportation, parks, health care and, in general, for more economic security, and Reagan tapped into this sense of workingclass panic. But instead of offering actual solutions, he offered a scapegoat—and then, he pursued policies that were mainly good for the very rich.

Again, racism was not the point. The point was to use racism to weaken government as an effective counterweight to the power of private wealth. In Reagan’s telling, government was the real enemy, showering people of color with welfare giveaways funded by tax dollars taken from white pockets. Reagan also picked up Nixon’s law and order theme, constantly criticizing government for weakly enforcing criminal law. The combined message was venomous: government coddled nonwhites with welfare and slap-on-the-wrist policing; meanwhile, government victimized whites by taxing their paychecks and refusing to protect them from marauding minorities.

Having peddled this poison, Reagan then hawked a supposed antidote, ultimately selling working families the policy preferences of the plutocrats. If government is the real culprit, Reagan said, then strike back: cut taxes; slash government spending; get government out of the ›marketplace. Over the course of two administrations, Reagan pursued these policies with the support of many Democrats, including many union members. But when he cut taxes, it was for the rich; when he slashed government spending, it was on social spending, while he increased corporate subsidies; and market deregulation meant corporate capture of the regulators, leading to market fraud and workplace abuses.

These are the years when wages stopped rising with productivity, when economic growth stopped driving better lives for average Americans, and when surging inequality began shoving the economy out of whack— and these trends have continued ever since.

Economists like Joseph Stiglitz, Robert Reich and Paul Krugman are all crystal clear on the main drivers of crippling economic inequality: weak unions, minimal government spending on education and infrastructure, tax cuts and trade policies set up for corporations, and regulations written by industry.3 Where they falter is explaining why so many voters—including union members—support these policies. Dog whistle politics helps answer that question. Popular support for the policies serving the rich has its roots in culture war politics, and mainly in race-baiting.

Bipartisan Whistling and New Enemies

If the basics of dog whistling were set in the Reagan years, three big changes have occurred since.

First, dog whistling became bipartisan. Bill Clinton campaigned and won on the following themes: ending welfare as a way of life; cracking down on crime; and curbing government spending. In other words, Clinton defeated GOP racial politics by imitating it. To be sure, Democrats have been less aggressive than Republicans in serving the interests of corporate elites.4 4 But even so, for the last three decades the fundamental pattern in American politics has been a dog whistle competition with both parties appealing to the racially anxious. The result has been an overall tracking to the right on key liberal markers. We would not have the pervasive cuts to the safety net, the dramatic rise of mass incarceration, the highest sustained levels of deportation the country has ever seen, or the shift to corporate-friendly market re-regulation had Democrats not frequently decided to adopt rather than oppose racial politics.

In the second big change, the racial boogeymen conjured by dog whistle politics expanded beyond African Americans. From Goldwater through Nixon and Reagan, blacks were the main targets.

After 9/11, new racial fears took hold nationally, one involving Muslims and another Latinos. Both were increasingly presented as dark-skinned foreign invaders, crossing our borders and threatening our way of life.

Fox News is full of dire warnings about radical Islamic terrorists penetrating the heartland. Simultaneously, almost no warning about the mortal dangers associated with “illegal aliens” sneaking across the southern border—they’re drug smugglers and rapists!—is too extreme for politicians to trumpet.

Third, as the 2012 election showed, dog whistle frames that once applied to nonwhites increasingly brand the working class generally. Mitt Romney’s infamous 47% video caught him explaining to his wealthy backers that he had given up on those in the bottom half of the country by income. These were people, Romney declared, who “are dependent on government”; “believe that they are victims”; think that they are “entitled” to health care, food and shelter and that “government should give it to them”; and refuse to “take personal responsibility and care for their lives.” Dog whistle politicians sold the country these narratives by applying them to blacks—but here was Romney, using them against working-class whites, too.

Romney lost, of course, and this may suggest to some that dog whistling, even as it has evolved, is losing power. But this ignores how Romney did among whites. Blowing his whistle, Romney carried three out of five white voters, not just in the South but all across country, including a majority of men but also of women, with Romney winning majorities in every age cohort, even among the youth.

At 59%, Romney’s percentage of the white vote has only been significantly exceeded twice in the last 50 years, by Nixon in ’72 and Reagan in ’84.

Yes, Romney lost the election, but if he had won just 3% more of the white vote, he would have won the popular vote nationally.5

And then in 2014, GOP candidates for Congress won that additional 3% of the white vote. Meanwhile, among whites without college degrees—the group once seen as the backbone of unions and Democratic power—64%, or nearly two out of three, voted Republican.6 Today the GOP draws well greater than 90% of its support from white voters, even as its elected officials are 98% white. From Reagan to Romney and now Trump, Republican politics depends on using race to scare fearful voters into supporting policies primarily geared toward helping wealthy elites.

Whites Aren’t the Problem

The constant talk of whites—of white voters, of white anxiety—might make it seem like all white persons are vulnerable to dog whistling, and by extension, that nonwhites are immune. Both notions are false. Susceptibility to dog whistling is not determined by ancestry: it does not afflict only persons of European descent, and minorities can be fooled by conservative racial appeals, too.

Dog whistling depends on “whiteness.” Rather than being a matter of biology, whiteness is a social orientation, a worldview. Those who believe in whiteness see lightskinned people as decent and deserving, and dark-skinned others as deviant and dangerous. To subscribe to whiteness is to believe that fair features make you a good person while darker color renders you less than fully human. This worldview may be openly held, as it is among Klan members and skinheads. Or it may be deeply internalized, a product of routine racism (more on the different forms of racism in the next part). Either way, it is not ancestry or features, but whether people tend to see the world around them in terms colored by racial stereotypes, that makes them prone to dog whistle manipulation.

Obviously, among those of European ancestry in the United States, many adhere to whiteness as a worldview. For example, the Fox News viewership is almost exclusively made up of whites (or more accurately, of those who uncritically accept the notion that they are white). These viewers tend—and are encouraged—to have a deep commitment to whiteness, to the belief that race reveals something important about human worth. That said, the overlap is only partial. Only about one in four whites is an avid Fox fan, and even if one includes every white person who votes Republican—and surely not all are driven to do so by racial anxiety—this is only three in five whites, meaning that at least 40% of whites cannot be readily manipulated through appeals to whiteness.

Meanwhile, whiteness is a problem among people of color, too. Even among minorities, large numbers adhere to the belief that color defines those who are makers vs. takers. One dynamic is racism between minority groups; another is racism within nonwhite groups. Not infrequently, the more privileged—in terms of color, education, social position and wealth—give credence to routine stories of racially coded worth and worthlessness. These people, too, can be convinced to vote their racial position against their economic interests.

Demography Will Not Save Us

Many seem to think that dog whistling is losing power simply because the number of whites in the country is falling. If whites are 62% of the population today, the Census Bureau tells us, they will become a minority nationally in less than three decades. Does this spell a natural end to racial manipulation in politics?

No. For starters, the social science is clear: as whites become aware that they are losing numerical supremacy, they generally become more racially anxious and shift rightward politically.7 This may be contributing to the Trump phenomenon. Richard Spencer, the head of a right-wing think tank, offers this explanation for Donald Trump’s popularity: Trump reflects “an unconscious vision that white people have—that their grandchildren might be a hated minority in their own country. I think that scares us. They probably aren’t able to articulate it. I think it’s there. I think that, to a great degree, explains the Trump phenomenon. I think he is the one person who can tap into it.”8

Far from convincing whites to get past race, constantly emphasizing changing demographics may perversely increase white racial resentment and thus create even more fertile grounds for dog whistle politics.

Also, the color line will likely shift. “White” in the United States expanded from those of English descent to include Germans and then the Irish, and then expanded further to include Italians, Poles and Jews. Today, the white category includes anyone of exclusively European descent. This is a story about a dynamic social category, not a fixed biological one, and we are likely in the midst of another rapid expansion in who counts as white. White identity is quickly becoming available to those of non-European descent, provided they are sufficiently light, with Anglicized names, excellent English, and high economic or professional status. Those who can now claim a white identity increasingly include light-skinned Latinos, East Asians and South Asians as well.

The current expansion of whiteness matters. To take just the case of Latinos, while the census predicts that whites will be a minority in less than 30 years, this is only true if the census excludes the large number of Hispanics who identify as white. If the census counts these white Hispanics, then the white population is expected to grow to 72%. Recall, the country is 62% white today. Instead of being in a period of contraction, we may be in the midst of a surge in the “white” population.

Notwithstanding rapid demographic change, we cannot sit back and wait for dog whistle politics to die a natural death. Dog whistle politics is a strategy. Power is the game, and those who stoop to demagoguery could not care less about recruiting some nonwhites or blurring the boundaries of white identity.

Dog Whistling Unions

Playing one race against the other long has been a foul tradition in the American workplace.9 Dog whistling carries this into the present, and expands it into the electoral realm, with right-wing politicians from Nixon to Trump winning support from union members through coded racial appeals. In addition, since the 1990s, unions themselves have become targets of dog whistle attacks. Business interests and their reactionary allies have tried to trash unions by tying them to people of color and government.

Public-sector unions have been especially vulnerable because they involve government workers, many of whom are minorities—a result of historically limited opportunities for blacks and browns in the private sector, as well as of government integration efforts.10 The right has seized on the confluence of state work by people of color to cast public unions as yet another example of the government subsidizing nonwhites. In this telling, (minority) public workers are lazy, incompetent and uncompetitive in the private marketplace, making public-sector union jobs just like food stamps—more government handouts to undeserving minorities.

Private-sector unions have not escaped taint, for the right repeatedly ties even these unions to government. Conservatives pillory private-sector unions as special interest groups that use the power of government to extract higher wages than they deserve. In this rendition, trade unions use laws requiring prevailing wages to shake down employers, making them “big government special interests” run by “big government union bosses in Washington,” to use Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s verbiage.

Conservatives are demonizing public- and privatesector unions the same way they once demonized poor black women on welfare. Unions and union members are the new welfare queens—painted as undeserving, scheming, irresponsible and larcenous.

And dog whistling is not just a problem in how the public sees unions. It also creates debilitating cleavages within the labor movement. For instance, private-sector unions have fallen for some of the rhetoric attacking their public-sector allies. When Wisconsin’s Walker went after public-sector workers using anti-government rhetoric, he simultaneously praised private-sector unions and workers and thus gained some of their support. But back in 2011, when a billionaire donor asked “Any chance we’ll ever get to be a completely red state and work on these unions,” Walker responded “Oh, yeah.” Then he explained: “The first step is we’re going to deal with collective bargaining for all public employee unions, because you use divide and conquer.” And so he did, eventually turning on the trade unions, too.11

Perhaps the greatest split in labor today involves public safety unions such as those representing the police, prison guards, firefighters and border agents. Partly, tensions between these and other unions arise because the former remain disproportionately white, a legacy of past discrimination. More importantly, the conflict stems from how they are positioned with respect to dog whistle politics.

Dog whistle politicians constantly drum out a message of danger from “criminals” and “illegal aliens,” and over the last few decades both political parties have competed to show who is tougher on these supposed threats. As a corollary, politicians frequently celebrate the police, prison guards and border patrol agents as heroes doing dangerous jobs that protect the heartland. But without taking away from the real dangers and stresses of public safety work, the dog whistle narrative about first responders is fundamentally racist: it’s a tale of saviors protecting white society from dangerous minorities. It’s one thing to talk honestly about the genuine risks faced by public safety workers; it’s another to constantly bolster racist stereotypes.

Beyond the rhetoric, in an era of otherwise falling wages and high unemployment, the massive build-up of police forces, prisons and border control facilities also has produced solid jobs. For unions representing workers in these areas, it can be difficult to look critically at the larger political context that is behind some of this. In the end, however, the truth of who benefits and who loses from dog whistle politics wins out. While with one breath they “support the police,” with the next conservative politicians endorse prison privatization and rail against government pension benefits previously common among all workers. Public safety workers should “think hard about where their better interest lies and who their true allies are,” warns Roger Toussaint, the former president of Transport Workers Union Local 100 in New York. He cautions, “Having worked to isolate them from the communities they serve as privileged and singing them praises as ‘the finest,’ ‘the bravest,’ ‘first responders,’ [the politicians] switched up on cops and firefighters, declaring their pensions to be ‘unsustainable’ and depicting them as undeserving recipients of welfare.”12

Sexual Orientation and Gender

Race isn’t the only dog whistle out there. Instead, race is part of a larger culture war that urges voters to resent other working people rather than focus on corporate power.

For decades, the right channeled fear and anxiety around sexual orientation into resentment of liberals and big government, for instance in campaigns against state-imposed “gay marriage.” The Supreme Court’s endorsement of marriage equality in 2015 reflects the power of social movements, and signals increasing social acceptance around sexual orientation. But it will not end anti-gay dog whistling. Instead, as in other areas, we should expect to see evolutions in the seemingly neutral terms used to mobilize gay panic. Two contenders already are emerging: the tried and true language of “states’ rights,” which pretends that the issue is the excessive power of the federal government rather than prejudice; and “religious liberty,” which insists that religious principle rather than anti-gay bias drives hostility toward sexual-orientation minorities.

Beyond sexual orientation, gender is another major culture war front. When Hillary Clinton backed health care reform in the 1990s, the right savaged her for promoting a nanny state—thereby casting good government as an overbearing woman that infantilizes men by presuming to take care of them. Similar gendered themes will proliferate in this election cycle, sometimes presenting Clinton as too feminine (weak, emotional, volatile), sometimes as not feminine enough (cold, uncaring, ambitious), and sometimes as feminine in the worst ways (domineering, manipulative, castrating).

Gender also will be a prominent subtext to the GOP campaigns against abortion and reproductive services. Couched in religious terms about the sanctity of human life, the abortion debate plays into narratives of Christians under attack and liberals as uncaring, immoral urban sophisticates. In addition, though, the raging debates about Planned Parenthood and abortion bans with no exceptions for the life or health of the woman call into question the place of women in society. Do virtually all women belong at home, serving as mothers and wives? Is it wrong for women to work outside the home, to pursue financial independence, or to be primary breadwinners? By politicizing women’s access to reproductive choices, the GOP stokes resentment against women who work— our sisters in the labor movement.

Gender also figures prominently in the workplace, making it easier for employers to devalue the work of women, especially women of color. Racism and sexism are not merely additive, each contributing its own independent quotient of burden. Instead, racism and sexism often combine to rationalize especially intense exploitation and dehumanization. From subminimum wage restaurant positions to domestic work and home care, from garment industry jobs to underpaid labor in fields and factories, many of today’s most vulnerable and exploited workers are women of color.13

Moreover, as terms like “crack babies” and “anchor babies” demonstrate, dog whistling frequently targets women of color as depraved or opportunistic mothers, and their children—even their infants—as criminals in training. The normal cultural reverence for mother and child often is reversed for nonwhite women—innocence replaced with guilt, celebration with condemnation, protection with persecution. In this context, unions must give special attention to the ways that gender and race structure unfair working conditions, and unions must strongly contest race- and gender-based dog whistling.

With union density at century-long lows, unions must look beyond their own borders and work on behalf of and eventually seek to organize broad swaths of unrepresented workers, many of whom will be people of color and women. Unions can do this successfully only by deeply engaging with how gender in addition to race has been used to erode worker solidarity.

The Racisms Underpinning Dog Whistle Politics

To really understand dog whistling requires a nuanced understanding of racism—or rather, racisms, for the racisms that support racial politics take many forms.

Many conservatives encourage understanding racism as just one thing, as hate. This sort of malicious racism describes Klansmen burning crosses, members of the Aryan Nation randomly attacking nonwhites with fists and bricks, or the hate-inspired murders in Charleston, South Carolina. Malicious racism is ugly, violent and socially destructive. Like just about everyone in society, those on the right condemn it.

But malicious racism, with its hooded robes, tattooed swastikas, and apartheid flags, is also easy to spot and relatively rare compared with other forms of racism, as we will see. Insisting that racism can only take this one form is political strategy, for this allows the right to claim that racism is largely past, and that whatever they are saying and doing, it cannot possibly be racist because they don’t regularly use racial swear words.

This is flat wrong. Racism takes multiple forms, and three in particular connect directly to dog whistle politics and debilitating economic inequality.

Coded Racism

Open racism long played a disfiguring role in American politics, but the civil rights era broke this pattern, making it impossible for politicians to win office by straight out promising to maintain white dominance. But that didn’t mean that race stopped being relevant to voters or that politicians stopped trying to exploit racial anxiety. Rather than ending, racism in American politics mutated and went underground.

Consider the following terms: welfare queen, thug, illegal alien, anchor baby, Muslim terrorist, inner city, the poor; hardworking Americans, decent folks, the silent majority, middle class, heartland. These are all “dog whistles,” words that are silent about race on one level, but that on another trigger strong racial associations in many who hear them. They are frequently used as coded racism: terms and ideas that do not expressly reference race and so seem race-neutral, but that incite powerful (often unconscious) racial reactions.

Coded racism works by invoking racial stereotypes— for instance, that whites are innocent, hardworking, endangered, and the “real” Americans; and that people of color are predatory, lazy, dangerous, and perpetual foreigners. The coded part comes in that politicians deploy these stereotypes without expressly mentioning race.

Politicians don’t say “black criminals,” “invading Latinos” or “decent whites”; instead, they warn constantly that “criminals” and those “invading” the country threaten “decent” people. The racial references may be missing on the surface, but many people nevertheless strongly absorb the underlying message of racial peril.

Routine Racism

Coded racism can sway broad swaths of the American public because racism is endemic in our society. The sad fact is, for most of us racism is routine. This may sound as if racism is no big deal, but the point is rather that racism is commonsense, forming part of our everyday understanding of the world, even for people who mean well, and even for people of color.

The burgeoning field of implicit bias helps us understand how our unconscious minds do much of our thinking for us, making snap judgments extremely quickly and outside our awareness. Regarding race, our unconscious minds automatically judge others, no matter how much we might try not to think in racial terms. The implicit association test available on Harvard’s website allows anyone to gain a sense of how unconscious racism shapes their judgments.14

We absorb stereotypes as a troubling part of our cultural inheritance, learned from family conversations, the media, classrooms and the workplace. Sometimes this ambient cultural racism takes the form of offensive “jokes”; sometimes it comes as supposedly “factual” claims about intelligence or the propensity to commit crimes; sometimes it appears in news images and film characters.

We also receive ideas about race from our environment, meaning our neighborhoods, schools, churches—and union halls. The labor movement bears the burden of our nation’s history, and history has consequences. Union membership, like home ownership, is part of the pathway to financial security, and patterns of economic exclusion, once established, are hard to change. We often talk of this in terms of structural racism, focusing on how past mistreatment set patterns that shape our present. These patterns seem to confirm that racial differences are real and explain group position as well as individual capacity.

Because of implicit bias as well as cultural and structural racism, for those reared in the United States, even the most well meaning cannot avoid seeing others through the lens of racism. Racism is the foundation for how we experience the workplace, politics and the larger world. It is this routine racism that allows dog whistling to succeed.

There are relatively few malicious racists today. Notwithstanding resurgent white nationalism, miniscule numbers believe in white supremacy and the inherent inferiority of the dark skinned. Instead, even as many whites are increasingly racially fearful, they’re also strongly opposed to obvious racism. This is where coded racism enters. Shaded terms may confound the critics, but more importantly, veiled language often hides the racism from those being racially manipulated. To his critics, Trump seems to have crossed into audible racism with his bald comments about Mexican rapists and banning all Muslims, but notice that he never uses racial epithets or talks about skin color. Such language would end his run, whereas Trump’s use of national origin and religion is just enough to allow his supporters to believe it’s not race that motivates their fears.

There aren’t enough malicious racists to elect anyone, so the key behind dog whistle politics is to reach decent folks who reject hate-filled racism, and yet remain trapped by routine racism.

Strategic Racism

Strategic racism is the most important racism undergirding dog whistle politics. All of those coded messages do not arise by accident. They are, instead, the work of GOP wordsmiths like Frank Luntz, think tanks such as the American Enterprise Institute, or media organizations like Fox News. Their goal is to carefully craft frames that spark racial anxiety, while hiding the racism from their opponents and, even more importantly, from their supporters.

This is strategic racism: the decision to manipulate the racial fears and hatreds of others for selfish ends. The “strategy” in strategic racism is to divide and conquer, and it has been at the core of American politics for the last half-century.

Strategic racism is critically important for two reasons. First, it gets us beyond the question whether dog whistlers are actual bigots. Does Trump really hate Mexicans and Muslims? Whether he does or doesn’t, it’s clear that he has made the calculated decision that attacking these groups is good politics—that purposefully fanning fear and anxiety can win him support. Ultimately, dog whistlers are pursuing a cold strategy when they raise the temperature in their followers. For demagogues, racism is a tool, a weapon, a strategy.

Second, the focus on strategic racism helps us see how racism hurts everyone, whites included. We typically think of racism in terms of intentional harm to people of color, and certainly that’s a huge element. But we lose sight of racism’s full power when we focus only on how it injures nonwhites, for dog whistling uses racism to structure the basic rules of government and the marketplace. As race scholar john powell writes, we need “a broader, richer understanding of race that is not only about individual, intentional, or unconscious discrimination against people of color.” Instead, we must develop an account of racism that stresses how “race, racial meanings, and racial practices are really about all people in the United States,” an account that specifically links “how racist attitudes, the creation of racial identities, and the institutionalization of racial systems are themselves tied to economic development and influenced by economic fears and needs.”15

Colorblindness

How can economic and political elites get away with stimulating racial panics when the country as a whole condemns open racism? Partly the right defends coded racism by insisting that racism must look like a Klan noose. When conservatives convince people that racism exclusively takes the form of malice, they prevent them from recognizing how dog whistling—rooted in code, routine and strategy—constitutes racial manipulation.

More deeply, though, the right protects dog whistle politics through “colorblindness.” Contemporary colorblindness claims that racism exists when race is expressly invoked, whether by a bigot or indeed by anyone. But clearly, in dog whistling the perpetrators talk in code, and it’s the critics who surface race. In practice, this translates into a standard dog whistle choreography of punch, parry, and kick.

- Punch racism into politics through repeated uses of racist stereotypes, though stripped of any direct reference to race. This is the heart of dog whistle politics. Here’s Trump’s version: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

- Parry claims of race-baiting by defending the original claims as supposedly race-neutral facts, and by interpreting the charge of dog whistling as an accusation of personal bias. Here, colorblindness helps shield against the charge of dog whistling by insisting that racism exists only if race is expressly mentioned. Trump again: “I can never apologize for the truth. I don’t mind apologizing for things. But I can’t apologize for the truth. I said tremendous crime is coming across. Everybody knows that’s true. And it’s happening all the time. So, why, when I mention, all of a sudden I’m a racist. I’m not a racist. I don’t have a racist bone in my body.”

- Kick back at critics, calling them the real racists for bringing up race. This draws on colorblindness again but now as a sword, for if racism involves mentioning race, then it’s the critic of dog whistling who is a racist for directly talking about race. When Washington Post journalist Jonathan Capehart criticized Trump’s “racist xenophobia,” the billionaire quickly shot back, “Jonathan—You are the racist, not I. Get rid of your ‘hate.’”

Defeating the punch, parry and kick of dog whistle politics is not hard, once you understand these stock moves. These feints only work when people accept the colorblind claim that racism requires that someone expressly mention race. The antidote is to expose and reject this claim.

First, far from requiring that race be directly mentioned to count as racism, racism today finds easy expression without direct references to race. The Confederate flag is a good example. Second, explicitly talking about race is not always racist. In fact, directly engaging with race is often the best way to fight racism. This makes sense, since sweeping problems under a rug and refusing to talk about them very rarely solves anything.

We all know that naming a problem is not the same thing as causing the problem in the first place. Jon Stewart put this in terms a fifth-grader would understand when reacting to a Fox News commentator who said, “You know who talks about race? Racists.” Stewart rejoined with ironic shock, “did you just ‘he who smelt it dealt it’ racism?”16 Among numerous other responses, one could also retort that dialing 911 doesn’t mean you committed the crime, and pulling the fire alarm doesn’t mean you set the fire.

Fighting Back

What follows in the remaining pages is a set of general suggestions about how to fight back, but two things are clear at the outset. First, if 50 years of dog whistling teach anything, it’s that ignoring it in the hope it will go away doesn’t work.17 Second, we know that progress in the labor movement must come by building from the inside out, addressing race-class connections internally as a basis for larger organizing. This will require sustained introspection and significant reforms. At the same time, unions cannot wait to complete such efforts before taking up externally focused organizing, educational and political work.

Asking the Race Questions

Unions should start by asking themselves probing questions about race (and gender) along the following lines:

- Integration—What is the racial composition of the local work force? Of the unions and of union leadership? What is being done to track these numbers and to foster integration?

- Separation—Are there local job sectors in which whites predominate, or that are largely occupied by people of color? In what sectors are unions more prevalent? What different issues do white and nonwhite workers tend to face, and what are the common concerns? What can unions do to make workers see the shared interests among whites and nonwhites as well as between union and nonunion working families?

- Discrimination—What is the history of discrimination within a job sector? Within unions? Do the effects of this discrimination continue? Does the discrimination itself continue? How is this affecting nonwhite lives? Does it create relatively privileged groups who might be susceptible to divide-and-conquer politics?

- Dog Whistling—Are coded racial appeals common in local politics? Are local unions targeted as havens for minorities or as big government special interests? Is there an effort to use race to win support from union members? How are union members voting, and what’s the connection to racial appeals?

- Attitudes—How do union members see each other across the color line? Is routine racism prevalent among union members? How many union members view whites as hardworking and responsible, and minorities as lazy and dangerous? How many believe that government and maybe unions themselves favor people of color over whites? Do nonwhite union members trust their white counterparts to do the right thing around racial issues?

Convincing Whites to Fight Racism

Turning now to general strategies, a key step is to convince whites to fight racism. This requires acknowledging that it’s often difficult to bring whites into the racial struggle. Partly, this is because few whites believe that race matters to them personally. Only 1 in 10 young whites report often feeling excluded at school or work because of race, or report being treated differently by an employer on the basis of race.18

More dangerously, many whites uncritically accept rightwing racial frames. For instance, most believe society should be colorblind. In a recent poll of young whites— those widely considered more comfortable with race than their elders—three out of four agree “society would be better if it were truly colorblind and never considered race or ethnicity.” Relatedly, most are skeptical that racism really harms people of color. More than three in five believe “racial minorities use racism as an excuse more than they should.” In addition, to the extent that whites feel threatened by race, it is as victims of what they see as anti-white racism, for example the “reverse discrimination” of affirmative action programs. Today, half of young whites believe “discrimination against white people has become as big a problem as discrimination against racial minority groups.”19

Given these views, to enlist whites it often may be counterproductive to exclusively emphasize racial prejudice against people of color. Having internalized the right-wing messages that it’s wrong to talk about race, that racism against minorities is largely past, and that society cares more about minorities than it does about them, the exclusive use of a racial prejudice frame runs the risk of playing into the right’s narrative.

It is imperative to broaden racial conversations to show whites how their lives are degraded by racial politics, not just morally, but economically. The noxious economic inequality that makes providing for a family so challenging is directly connected to political exploitations of racism. To enlist many whites in the battle against racism requires demonstrating to whites that by voting according to dog whistle appeals, they’re wrecking their own lives—their work conditions and wages, their pensions, their health care, the education and future of their children. Conversations about race must sometimes stress how whites lose when racism wins.

Convincing People of Color to Connect Race to Class

Those focused foremost on the very real harms suffered disproportionately by black, brown, red and yellow communities in the United States may bristle at the suggestion that conversations about racism should emphasize harms to whites. At the very moment when energy is gathering behind the slogan “Black Lives Matter,” this may seem an effort to steal attention by proclaiming “all lives matter.” Thus it’s critical to emphasize that racial justice is in no way being shoved to the back burner. On the contrary, a racial politics approach can advance racial justice more than can a racial prejudice frame.

The dog whistle lens helps bring into focus the political roots of some of today’s worst racial injustices. Reconsider police violence against minorities. When Richard Nixon threw himself into dog whistling, the number of people in state and federal prisons serving a year or more behind bars stood at around 200,000; today we have more than 2,300,000 persons in prison cells.20 Republicans started the drum beat about blacks as marauding criminals and whites as innocent victims; Democrats soon picked up the same themes, and then both parties were boosting aggressive policing, building prisons and filling them. Politicians, not the police, created a climate in which massive violence against nonwhites became the norm. This same story can be told in many areas, from disinvestment in urban areas and schools, to mass deportation campaigns.

Many of the largest calamities that have beaten down nonwhites over the last 50 years didn’t just happen; they were instead collateral fallout from dog whistle politics.

In addition, emphasizing how racism hurts whites is an important racial justice strategy in its own right. Pragmatically, whites hold most of the power in society, which means that fundamental racial change is much more likely when substantial numbers of whites support it.

On the negative side, the power held by whites means that if most of them mobilize to oppose racial reform, little real change will occur, and some things may get worse. This is the story of dog whistling. The very success of the civil rights movement created an opening for reactionary politicians to step in and harness white fears, not only curbing the civil rights movement, but also undoing significant achievements in progressive governance.

On the positive side, the political power of whites argues for affirmatively enlisting whites in racial justice campaigns. Derrick Bell, the first African American professor at Harvard Law School and one of the most astute voices on race in the post-civil rights era, labeled this basic truth “interest convergence.” As Bell recognized, in any campaign for racial justice, there are many whites who will join the fight because it’s morally right. But inevitably, “the number who would act on morality alone is insufficient to bring about the desired racial reform.”21 Instead, powerful blocs of whites must come to see the demands for racial justice as aligned with their own interests. Those concerned foremost with the fate of minorities should embrace desegregating the race conversation by showing whites how racism hurts them, too. Genuine progress on race will come most rapdily when large numbers of whites feel they have a direct stake in challenging racism.

Self-Interest

Despite the stress on practical interests above, it’s also clear that this emphasis can be carried too far. Indeed, focusing almost exclusively on economic issues is perhaps the key mistake progressives have made in confronting culture war politics.

As early as 1970, Democratic leaders saw that race and other wedge issues could be successfully used to divide their supporters. At that point, liberals made a fateful decision: pull back from race and other controversial social positions, and instead emphasize pocketbook concerns. The calculus seemed simple and straightforward: since people seemed motivated mostly by their bottom line, stress economic over social matters. Or, put another way, if the key was “self-interest,” liberals put all the emphasis on “interest” and largely neglected the “self.”

Conservatives did the opposite. While they offered phrases like “trickle-down economics” and “job creators” to pretend that voting Republican made financial sense for the working class, more than anything else, the right stressed threats to the self, to people’s sense of position in society. What it meant to be white in America—as well as what it meant to be a husband or a wife, a Christian, an American—all of these were under siege, the right insisted, from insurgent minorities, organized labor and their big government allies. Dog whistle politics is fundamentally a manipulation of anxiety about eroding social status.

To respond successfully to this strategy, in addition to laying bare the economic consequences of racial politics, labor also must strive to give people a new, positive sense of themselves.

Beyond emphasizing wages and work conditions, the labor movement should work to build pride in an inclusive identity resistant to divide-and-conquer tactics—an identity of people for each other, not fearful of each other.

Key components of this new identity should include staples like pride in the country and pride in hard work, whether in the trades, at home, in government service or in the private sector. But most importantly, an inclusive identity should be built around belonging, mutual respect, and mutual care: belonging, the grounded sense that we all are members of this society in equal standing; mutual respect, seeing the basic humanity and dignity of others, even when we’re different; and mutual care, the pride and security that comes from taking care of each other, offering help when we can and accepting help when we need it, confident we’ll be able to return the favor soon.

The overwhelming majority of Americans understand that we owe each other a basic duty of care.22 The power elites have skewed this, however, by stoking fear and anxiety, causing people to severely constrict their circles of concern. Thus it is not enough to talk only about pragmatic interests. To defeat decades of resentment-based politics requires fostering pride in a renewed conception of what it means to be American. Only in seeing ourselves in others—without regard to race or other social prejudices—do we gain the power to create a society where all can flourish. This has to be one of the core lessons that labor seeks to teach.

Building a Movement

The need to lift up a new sense of belonging implies the need for unions to participate in something bigger than labor actions. Unions should see themselves as key drivers of a new social movement with roots in the workplace that aims to give all Americans a reinvigorated and inclusive sense of shared purpose.

The energy for mass mobilization is there, evident in the last few years in the popular campaigns supporting everything from immigrant rights, Barack Obama’s initial election, marriage equality, and a living wage, as well as in the Occupy Movement, the outrage in Ferguson and Baltimore, and in Black Lives Matter. Indeed, even the passions animating the Tea Party show that people sense things are going off the rails and that it’s time to put things straight again.

How can we convert this energy into a broad movement for progressive social change? Social movements require, at root, three things: narratives, networks and resources.

Narratives refer to frames or stories that help people comprehend the world, explaining why current crises reflect injustices rather than accidents. If people perceive hardships as “accidents,” they typically respond as if there’s nothing to be done. But an “injustice” can be fixed, and indeed demands corrective action. Unions are in a strong position to craft these narratives, educating their members and the broader public about how the plutocrats have been manipulating us through the politics of resentment while they seize ever more power and wealth. We need a clear, simple message that we should care for each other, and that government and the market can and should serve everyone and not just the very richest.

Networks are important for disseminating ideas within and between groups, and for supporting people in the decision to stand up. Narratives of injustice are useless unless broadly shared, at which point they can help solidify a sense of unifying purpose among groups working on different fronts. The labor movement has the capacity to make these links, building connections to groups working on everything from housing, the environment, and campaign finance reform, to mass incarceration, immigration, and public health. Moreover, networks are important in getting people off the couch.

Isolated in their misery or fearful of others, individuals stay home.23 But connected to others, indeed, fighting for others, people take to the streets.

Resources include the financial wherewithal to fund the movement, of course, but at least as important, they encompass the myriad skills required to shape messages, disseminate ideas and organize people. Here again, unions are better positioned than most others to take the lead.

It is not just the need for a renewed sense of solidarity that makes a broad social movement necessary. In addition, contemporary electoral realities necessitate a grassroots response. Big money has largely captured both political parties, a trend that has exploded since the Citizens United decision. The Koch brothers alone have committed to spending nearly $900 million in the 2016 election cycle—on par with the spending of the two major parties in the last presidential election.24 With politics awash in this kind of money, the only possible response is popular mobilization. The only counterweight to the power of money is the power of people.

Good Government

The most important single goal unifying any new movement should be this: to demand that government serves people rather than money power.

Government sets the basic rules of our society, and today those rules keep the incomes of the majority of us down while concentrating more and more wealth in the grip of the very richest.

To have the power to take government back from these economic titans, a movement must first build power in workplaces and in communities. We cannot seek the blessings of the state before acting. Where, as now, politicians largely serve the interests of the power elites—or whites continue to control government with little regard for people of color, as in Ferguson—we must often mobilize against government.

Even as we do so, though, we must remember that “government” is not coterminous with venal politicians, however much damage they may do. At its base, government is composed of people who have dedicated their lives to public service, whether as teachers or safety workers, judges or office clerks, inspectors or social welfare case workers, and many of these folks are union members. We must avoid the dog whistle rhetoric that trashes government, including many of our brothers and sisters.

In protesting government, the point is not to reject it—this is what the right wants working people to do—but instead to reclaim it and demand that it fulfill its mission of pursuing the good of all.

The labor movement’s history illustrates this. Mass movements in the workplace originally faced government repression in the form of police clubs and militia guns. But these movements eventually generated political as well as economic power. Lasting gains in the workplace only finally occurred when the labor movement built sufficient political support to secure state and federal laws that protected workers in their right to organize and bargain. In contrast, after Taft-Hartley, Reagan, and the accelerating proliferation of “right to work” laws, government increasingly has made collective action among laborers more and more precarious, contributing directly to the withering of unions and the savaging of the working class. We must protest this shift, not with an eye toward doing away with government, but with the aim of wresting government out of the grip of big money and bringing it back onto the side of workers.

Short Term/Long Term

The right has been using dog whistle politics to stampede voters and demonize government for 50 years. This may seem like a long time, but in reality this is only the latest maneuver in the perpetual campaign by privileged classes to amass ever more lucre

In the face of constant efforts by the rich and powerful to grab more and more, the struggle of human societies is always to push prosperity downward and outward. This is, by necessity, an enduring fight.

Of course we must act in the present and accomplish today what we can. But it is a huge mistake to act exclusively with short-time horizons. In particular, election cycles should not set the limits of union strategizing. Just as Goldwater pioneered dog whistle politics and lost, only to see Nixon win big with the same approach eight years later, progressives must look further down the road than the next election. Movements are made through groundwork, which can only be laid between elections rather than in the midst of heated campaign seasons.

Plutocrats have largely hijacked the marketplace and government, winning support by convincing many to fear their neighbors while ignoring toxic social and economic inequality. We need to act immediately to combat this, understanding that it will require a long-term effort to build a renewed sense of belonging and mutual care in America.

- 1Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data,” NBER Working Paper, October 2014. 1

- 2Quoted in Ian Haney López, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class, 211 (2014). Other unattributed quotes and statistics in this paper are from this source.

- 3Paul Krugman, The Conscience of a Liberal (2007); Robert Reich, “Inequality for All” (documentary), http://inequalityforall.com; Joseph Stiglitz, The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them (2015).

- 4Larry Bartels, Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age (2008).

- 5 Chris Cillizza, “How many more white votes did Mitt Romney need to get elected in 2012? A lot.” The Washington Post, Aug. 4, 2014.

- 6Thomas Edsall, “The Demise of the White Democratic Voter,” The New York Times, Nov. 11, 2014.

- 7Maureen A. Craig and Jennifer A. Richeson, “On the precipice of a ‘majority-minority’ America: Perceived status threat from the racial demographic shift affects White Americans’ political ideology,” 25 Psychological Science 1189 (2014).

- 8Evan Osnos, “The Fearful and the Frustrated,” The New Yorker, Aug. 31, 2015.

- 9David R. Roediger and Elizabeth D. Esch, The Production of Difference: Race and the Management of Labor in U.S. History 5 (2012).

- 10Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor 182, 260 (2013).

- 11 Jason Stein and Patrick Marley, “In Film, Walker Talks of ‘Divide and Conquer’ Union Strategy,” Journal Sentinel, May 10, 2012; Dan Kaufman, “Scott Walker and the Fate of the Union,” The New York Times, June 14, 2015.

- 12Quoted in Sarah Jaffe, “Black Labor Organizers Urge AFL-CIO to Reexamine Its Ties to the Police,” Truthout, Aug. 13, 2015.

- 13Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, Tipped Over the Edge: Gender Inequity in the Restaurant Industry (2012).

- 14Project Implicit, https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html.

- 15john powell, “The Race and Class Nexus: An Intersectional Perspective,” 25 Law & Inequality 355, 358–59 (2007) (emphasis added).

- 16Daily Show with Jon Stewart, “Race/Off,” http://thedailyshow.cc.com/videos/ufqeuz/race-off.

- 17Social science teaches the same lesson. Tali Mendelberg, The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality (2001).

- 18David Binder Research, “MTV Bias Survey II Final Results,” April 2014.

- 19Ibid.

- 20Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2010).

- 21Derrick Bell, “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma,” 93 Harvard Law Review 518, 525 (1980).

- 22Benjamin Page and Lawrence Jacobs, Class War? What Americans Really Think About Economic Inequality (2009).

- 23 Robert Putnam, “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the 21st Century,” Scandinavian Political Studies, June 2007.

- 24Nicholas Confessore, “Koch Brothers’ Budget of $889 Million for 2016 Is on Par With Both Parties’ Spending,” The New York Times, Jan. 26, 2015.