A new report describes the relationships between the health of Detroit’s residents, housing, and disparities in political power. What has and is happening on the ground in Detroit showcases what happens when decisions around healthcare policy are limited to interventions inside the clinic and exclude the promotion of physical health through interventions outside the walls of the clinic—so called social determinants of health.

The report reveals that water and sewer infrastructure and housing are key points of intervention to create better health for Detroiters. It suggests that this narrow approach to healthcare policy has become a hallmark of such policy tied to corporate sectors in the healthcare industry. Political debates trade on language that erodes popular support for social safety net programs—like Medicare and Medicaid—by relying on stereotypes and generating resentment for sharing public resources with stigmatized groups, including low income people of color.

Rearrangements of traditional economic and government practice can ameliorate these detrimental effects and create the basis for ongoing systemic change for equity and inclusion. And, in the case of Detroit, the potential for new arrangements of government, public, private, and policy can hold promise to exceed the problems of the past arrangements.

The report discusses how the declining wealth and health of ordinary Detroiters has most recently been felt by their suffering in relation to safe, affordable, and available water, and the housing crisis. Specifically, this report explores the paradox and potential of Medicaid Expansion (or the Healthy Michigan Plan) for Detroiters in the aftermath of the city’s bankruptcy. The paper examines efforts at leveraging health equity, via Medicaid Expansion, to the backdrop of toxic policies of water and housing insecurity, experienced by Detroit residents.

Losing access to consistently safe housing and water is an existential threat and presents challenges to individual and population health. Communities have organized, supported one another, created multiple versions of alternative plans for water infrastructure, and see beyond simple survival. Teachers, neighbors, families, churches, and local organizations have figured out what role they can play in providing emergency assistance. Most importantly, the city and its residents see, expect, and demand more for their neighbors and community. They want the city—including its water utility infrastructure—to create a sense of belonging and inclusion. They want the city to exceed its former standards—not just survival.

From housing to physical health, Detroit’s lack of clean water remains a critical problem that must be solved and is an example that can be instructive for other places. The United States, Michigan, and Detroit can do more to find policy to survive and persist. As critical infrastructure ages across the nation and as climate change adaptation raises the bar for what is demanded of it, it’s clear that Detroit is a signal of what is to come in many more places. It’s a problem in need of innovative solutions which would be of benefit too all.

In the case of the US federal government, the state of Michigan, and the city of Detroit, the paper uses clinical and non-clinical determinants of health to analyze the federal investment represented by Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Simultaneously, this investment is put alongside the health challenges presented by the nexus of housing and water shutoffs in Detroit.

Introduction

THIS REPORT EXPLORES THE paradox and potential of Medicaid Expansion (or the Healthy Michigan Plan) in the aftermath of Detroit’s bankruptcy. In particular, it examines efforts at leveraging health equity, such as Medicaid Expansion, within the backdrop of toxic policies of water and housing insecurity experienced by Detroit residents.

Michigan’s Medicaid Expansion, particularly in Detroit, can be viewed in at least three critical ways. First, Medicaid Expansion has been a way for the federal (and state) government to increase access to medical care to vulnerable communities in Detroit who have recently (and historically) experienced economic crisis (in housing, social services, water, education and work).

Second, Medicaid Expansion was a way for the Obama administration to infuse federal funds into states and distressed municipalities.

Third, Medicaid Expansion has been a way for the Michigan Legislature to access federal dollars by pursuing decades long economic policies and thinking about who is deserving in US society. This economic and social philosophy has meant the expansion of a hyper-deregulated safety-net program like Medicaid, the profound capture of government and public funds by corporate healthcare interests, and the insistence on personal responsibility from the poor and marginalized.

Most significantly, Medicaid continues as an austere, stigmatized, and segregated program that continues to separate the US population (into low-income, seniors, those who are pregnant, or those with employer-linked benefits) and deny universal healthcare to all in this country. Michigan legislators managed to change federal Medicaid rules by including legislation that has vulnerable populations demonstrate more “skin in the game” and “personal responsibility.” Thus, low-income people and communities of color in the city, who continue to experience racial and class injustice, economic instability and compromised social services, are expected to be prudent price-conscious consumers in order to bring down costs for government and industry.

Borrowing from and building upon the works of several scholars, I use the term structural violence to describe political, economic, social and psychological processes that severely compromises individual and community health and opportunity.2 The social and physiological traumas experienced by residents of Detroit due to the water and housing crisis is an example of structural violence. Medicaid expansion in Michigan has been one avenue through which governments have sought to interrupt glaring health inequities generated by structural violence.

In this report, structural violence refers to systematic ways in which multiple structures of injustice can come together to harm, restrict, contain, and disadvantage individuals and communities. Multiple systems of inequity co-exist, intersect, and simultaneously disadvantage individual/community material, psychological, and biological well-being (structured by race, gender, class, sexuality, age, and citizenship). This experience, both ongoing as well as historical, of structural violence promotes a continuous transfer and removal of wealth, health, resources, and opportunity for Detroit’s low-income communities, particularly communities of color.

As systemic and daily phenomena, structural violence is embedded within systems of injustice and the bodies and lives of vulnerable communities/individuals. Scholars have pointed out that in addition to being exposed to and succumbing to more systemic stressors marginalized people are at greater risk for infection, slower recovery and unfavorable outcomes such as death. Trauma associated with daily social and economic oppression are marked upon bodies, psyches and life chances.

Structural violence is also used in this report to connect what is deliberately compartmentalized as clinical and non-clinical aspects of life. And, to propose, like many others, that the health of individuals or communities suffer when systematic policies around work, housing, lending, redlining, reverse redlining, foreclosures, state and private violence, unemployment, social exclusion, neighborhood safety and investments, water and sanitation equity, and transportation deepen vulnerability to illness. Structural violence includes supremacist systems such as racism and sexism that intensifies economic inequities, but also economic policies of austerity imposed upon Detroiters by governments and corporations that compound racism and sexism.

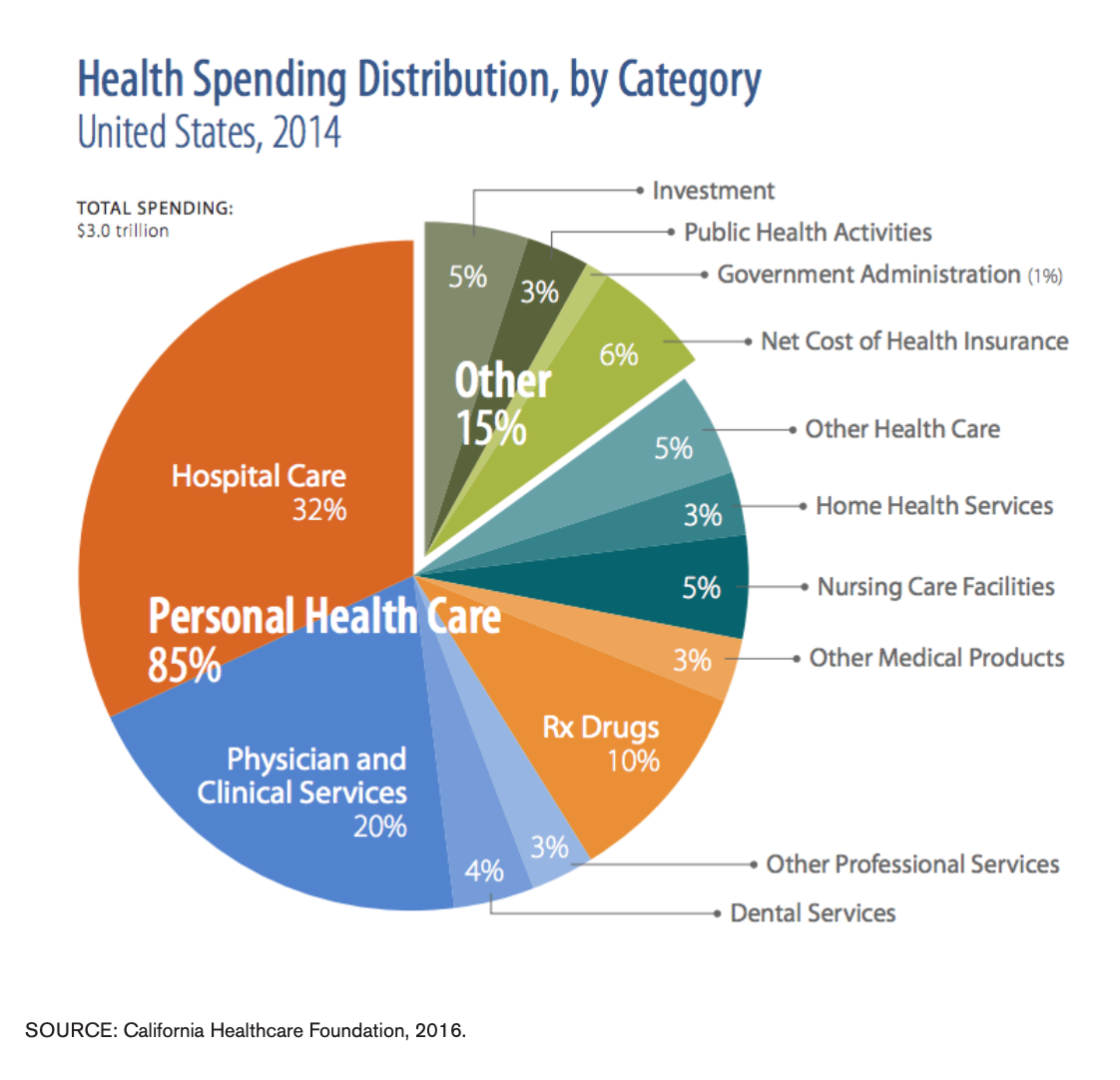

Public health practitioners and scholars have used the term “social determinants of health” and "toxic stress" to describe how social conditions or one’s environment influences exposure to disease, chronic illness and health outcomes. The term structural violence seeks to build upon the term “social determinants of health” to interrupt the dominance of clinical, behavioral and biological frameworks used in public policy. For instance, many studies have shown that US has the highest healthcare expenditures but unimpressive health outcomes amongst countries of the global north. On unpacking these reports scholars3 have shown that (1) while these healthcare expenses are indeed high, most of the funds go to hospitals, physicians, clinics, and other biomedical investments; (2) health in healthcare is almost always underscored by a clinical or biomedical worldview at the expense of the political, economic and social dimensions of health; and (3) by not investing in social services (housing, water, economic security, education, transportation, and avenues to challenge discrimination or segregation) to interrupt structural violence, health outcomes continue to be a troubling representation of toxic inequities and chronic suffering (see Figure 1).

Structural violence also attempts to underscore how power and its multiple policies/practices of social injustice can afflict individual and community well-being well before needing health care in a clinical setting. “Health begins where we live, learn, work and play,”4 and, health should not be continued to be compromised by the abuse of power and social injustices where we live, learn, work and play, or due to lack of access to clinical care.

Detroit: Restructuring a Shrinking City

The city of Detroit is an iconic example of how the predispositions of the US economic and public health systems and welfare capitalism can fail individuals, communities and cities. The city showcases how the whim of capital and governments generates economic instability, economic revitalization, persistent racialized and class injustice, physical and psychological distress on community health, and hardens and reorganizes old and new inequities.

Detroit residents are accustomed to some of the highest water and sewerage rates in the nation, and many live in “housing stock” considered to be of poorer quality, undervalued, and over-taxed. While not uniformly poor, Detroit’s downtown, midtown and Corktown suburbs have experienced significant economic revitalization and investment zones,5 thanks to the concentration of political and economic power in those neighborhoods. Other parts of the city have a 40% poverty rate, 2.3 times higher than the state of Michigan and over 2.5 times higher than the US poverty rate. Regionally, Detroit’s homeownership is at 50.7% (with the median home value at $45, 000) compared to 71.5% in Michigan and 64.4% in the US.6

Multiple accounts have described and identified Detroit’s loss of its tax revenue/base, people, communities, social services, opportunities and work that have been driven by factors including: disinvestments from its monolithic auto-industry; neoliberal government strategies; policies of racial injustice, including punitive policies of mass incarceration;7 white and middle-class flight to the suburbs; and, redlining. Simultaneously, individuals from low-income communities of color, have been locked within a city that does continue to tax residents at higher rates but not guarantee quality and uniform neighborhood development, services, and infrastructure (water, housing, work possibilities, safety from state and non-state violence, education, and transportation).

Detroiters who stayed in the city were rocked by the most recent incarnation of the economic downturn of the housing crisis and the “Great Recession” in the 21st century.8 In December 2013, Detroit officially filed for federal bankruptcy protection9 and after 17 months, in December 2014, the city formally exited from the largest municipal bankruptcy.

The declining wealth and health of ordinary Detroiters has most recently been felt by their suffering in relation to safe, affordable, and available water—material, that many residents have reminded, is of essence to bodies of individuals, communities and cities.

Water and Well-Being

The Charter of the City of Detroit, Declaration of Rights, provides that “the people have a right to expect city government to provide for its residents safe drinking water and a sanitary, environmentally sound city.” DWSD, therefore, has a mandate to advance universal access to water and sewer services.

“Water should be a human right. You know, you can’t live without water. You have to worry about where you’re going to shower when you go to work. How can you cook your food if you don’t have water to rinse it off, or to wash your pots and pans? You can’t wash your clothes...and there are people being shut off who have children.”

MASS WATER SERVICE SHUT OFFS are not something new for Detroit city residents behind on or unable to pay their water bills (see Fig. 2). In 2005 alone, 42,000 Detroit households experienced shut offs. That same year members of the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization drafted a “Water Affordability Plan” (WAP) and presented it to the city council. This was accepted by the city council but was not implemented. Instead the city council came up its own “Detroit’s Residential Water Assistance Program (DRWAP).”

The WAP proposal called for a payment plan that is income subsidized and determined by the ratio of household income to the utility bill. Proponents of this plan pointed out that many Detroiters pay more than 20% of their income on water bills and believe that the utility bill should not exceed more than 2% or 3% of household income and cover those at or below 175% FPL.12

DRWAP was aimed towards low-income residents, at or below 200% FPL, living in single-family households, whose water services was shut off or facing one. Critics of this policy pointed out that only 300 out of the 24,743 enrolled residents have not defaulted.

The WAP proposal resurfaced again in October 2014 by various coalitions, including the Detroit People’s Water Board and the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, in response to more water shut offs,13 skepticism over sustainable assistance, a statement released by a visit by representatives of the United Nations,14 and a new plan implemented by Mayor Duggan and the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department (DWSD).15

The Mayor’s plan is referred to as the “10-Point Plan” or the “10/30/50 Plan” and was implemented in August 2014.16 Concurrently during this period was the creation of a new regional water authority (The Great Lakes Water Authority).

Kevyn Orr, the Emergency Manager, the Detroit City Council along with Mayor Duggan, and the State of Michigan under Governor Snyder, all negotiated the final bankruptcy-restructuring plan for the DWSD, which was approved by US bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes. Under this arrangement, also known as the “Grand Bargain,"17 the DSWD maintained the ownership of the water and sewage infrastructure and leases the water and sewage system to the newly created Great Lakes Water Authority, formally approved in October 2014. The GLWA controls the operations and the management of the forty-year leasing arrangement of the water and sewage system. The forty-year lease of the water and sewage infrastructure is to bring in $50 million per year to Detroit) with approximately $4.5 million set aside to help low ncome residents in the city to pay utility bills)—is to go towards the upgrade and maintenance of the aging infrastructure.

This water and sewerage system provides services for eight counties, four million people and covers almost 1,100 square miles, with 75% of the customers living in the suburbs. The GLWA, which commenced operations on January 1 2016, is comprised of six appointees (two appointed by the Detroit Mayor; county executives from Oakland, Wayne and Macomb county; and one appointed by the Michigan governor) who then make key decisions about the budget, debt issuance, operations, pricing, rates, labor agreements and contracts, and decision-making regarding the water and sewage. The Governor’s appointee represents additional counties such as Genesee, Washtenaw and Monroe.

It is hard not to ignore the post-bankruptcy reality of this “special purpose government” of the Authority where the residents and city of Detroit is saddled with the disproportionate cost burden of an oversized aging infrastructure (with upgrades, maintenance, and water main leakages), weakened representation, and decision-making power. And, to also wonder to what extent the most vulnerable members of Detroit shoulder the burden of aging oversized water and sewage infrastructure costs for the other wealthier counties and residents of SE Michigan. Costs that some believe are underestimated in the annual $50 million figure. Many of Detroit’s water pipes were laid in the early to mid 1900s and has been part of a system that was designed for a population over $1 million.

To qualify for the 10 Point Plan residents with overdue bills and penalty fees, first have to pay upfront 10% of the overdue bill and the rest over a 24-month period. If one defaults, the water is shut off, one re-enrolls but now one has to pay 30% of the bill upfront and pay of the rest over 24-months. If you default for second time, the same process but one pays 50% of the remaining bill upfront.

In March 2016, another plan, the Water Residential Plan (WRAP) was launched and administered by the Great Lakes Water Authority (GLWA). WRAP co-exists with Duggan’s earlier 10/30/50 Plan is offered in counties including Wayne, Oakland and Macomb. WRAP provides qualified low-income households with credits and freezes 12-month arrears and delinquencies. Critics of this plan have pointed out that ¾ of Detroit customers are behind in payments and around 3000 are on a waitlist to receive credits.

Some Detroiters observed that, “Indebtedness isn’t treated equally in our society.”18 In other words, they argued that the DWSD was being tough on low-income people’s crimes of indebtedness and whole lot more lenient on water and sewerage debts owed by large private and government owned businesses such as the Joe Louis Arena, the Ford Field or the Palmer Golf Club. The large businesses owed anywhere from $55,000 to $200,000 and still had their services, whereas the water was shut off for a low-income single mother who owed more than $150.19 In October 2015, this practiced was confirmed by Gary Brown the new Director of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. Additionally, a report also reiterated this point by identifying that in 2015, 1 out 9 the city’s 200,000 residential accounts were disconnected, compared to 1 in 37 of the city’s 25,000 non-residential accounts.”20

Figure 2 highlights the see-saw of shutoffs and reconnections pre-, during-, and post- bankruptcy. Another resident commented on the current shut offs, pre-and post-bankruptcy, by pointing out that, “the bankruptcy was about the water, the water was not about the bankruptcy.” She felt that the fee hikes and shut offs are part of making it more appealing to private investors. And that water and sewage shut offs directed at poor Detroiters is simply a way to clean out existing neighborhoods for proper development of the land of a “shrinking” city.

Some have also observed that the DWSD passed on the increased costs of the water leakage (due to aging infrastructure costs, lack of reinvestments, and ineffective home plumbing) on to residents and made errors on bills. By raising their water rates by 8.7% the bills were unaffordable for communities and individuals living under the federal poverty levels and/or low-income people. And, billing errors by DWSD resulted in water shut offs. A resident that called into the water hotline for help mentioned that her water got shut off at the place she rents because the landlord did not pay the water bill (despite the fact that she had made arrangements to pay her landlord for water). Water and sewage rates have risen in the city by 8.7% in 2014. In 2015, the DWSD announced a rate increase of 3.4% for Detroiters, including a 16 percent increase for the sewerage portion of the bill.21

In Fall 2015, the city commissioned Blue Ribbon Panel Report, and the authors have identified these and many additional issues that speak to the “affordability dichotomy” where pricing increases due to aging and unmaintained infrastructure costs are borne on the backs of the remaining low-income and primarily African American residents.22 The authors point out that Detroit’s water and sewage plants were built in the 1940s to originally serve approximately four million residents. Additionally, the report highlighted that while Detroit represented 20% of the service area population a disproportionate amount of service debt (51%) is allocated to the city. The report also found that the service debt was even more acutely felt by a declining populace (now just below 700,000) through decade long water and sewage rate increases.

The city of Detroit, the state of Michigan and the US has experienced enormous regional variation and disparities in water and sewer services. So, for instance, in 2009, the average water and sewerage bill in Detroit was $62.75 and the same month it was $26.56 in its suburbs. In their study, Butts and Gasteyer found that higher rates are often associated with places with residents of “minority racial status,” “postindustrial divestment,” and depopulation. They argue that, in cities such as Detroit, the fixed costs of water infrastructure coupled with decreased demand for water/ sewage service due to fewer remaining people/ households contribute to rising water rates for an increasingly disenfranchised segregated population. This fixed cost burden, which is shifted onto a “shrinking” and vulnerable population, also has to contend with an aging infrastructure that has costs related to repairs and maintenance. In 2002, the DWSD estimated that it lost 35 billion gallons of water (about $25 million in cost) due to leakage associated with an aging water infrastructure.23

Wallace Turbeville has pointed out that a mixture of an acute city government revenue decline coupled with an escalation of financial expenses fast-tracked Detroit’s bankruptcy. The “financial expenses” refer to bond debt servicing payments and fees or expenses directly resulting from a buildup in risky bond debt with private banks that the city entered into since the early 2000s. Participation in these risky municipal bonds was directly linked to the downgrading of Detroit’s “credit worthiness” status.24 According to one report, the CFO of DWSD acknowledged the urgency of clearing Detroit’s “bad debt” through mass water shut offs to improve the city’s credit rating credit rating agencies.25 According to official estimates (determined under the Emergency Manager) the $5.8 billion debt owed by DWSD to the overall debt is a liability of the city of Detroit.26 Detroit residents comprise of about a quarter of the population served. This disproportionate amount many observers suggest, should not be the city’s liability.

Some local residents believe that the DWSD is a key public asset that is in the process of being “privatized” after it was restructured into a new regional government entity, The Great Lakes Water Authority—with unproven benefits to residents. And, that the organizational and political separation and transfer from city to authority and eventually private corporations was one of the key strategic goals of the Emergency Manager. Others residents believe that relieving a dysfunctional, inadequate and corrupt city government from functions such as water/sewerage or transportation services into quasi-public authorities is the way to restore needed services to all Detroiters. These quasi-public or private-public entities, some regional and others local, proponents argue would go beyond the inefficiencies of city government and the callousness of large auto corporations, actors who have both contributed to Detroit’s financial crisis.

Several local residents and writers have raised the issue of “water as a life giving and sustaining” substance and the highly undemocratic nature of the shut offs. Biology teaches us how the lack of water negatively impacts the human body. Water is a major component of our bodies and lack of water consumption can interfere with temperature regulation, metabolism, the flushing of waste/toxins, hydration and many important functions. So, preventable issues such as dehydration, stroke, seizures, and the protection of organs, bones, muscle, and blood depends on regular intake of clean water. Such preventable conditions such as lack of clean and accessible water can add to one’s disease burden and mortality, especially if a person already has a chronic condition or disability.27

Water is also needed for a nebulizer machine for patients, like 12-year-old Aldontez, who had acute asthma, so that he could breathe. Water is also needed for oxygen tanks for patients like Nicole, who is fighting “… scarcoidosis, an autoimmune disease that affects the lungs and other organs.” The scarcoidosis was intensified by the mold in her Section 8 subsidized rental and she was trapped in this rental because she couldn’t transfer the subsidy to a new place due to her $3000 overdue water bill.28

Water, especially clean water, is needed to drink, cook, flush and clean toilets, clean bodies, clean human waste, external and internal wounds, clothes, food and homes. If water is not accessible for any one of these purposes individuals have to expend time to find them at the cost of not doing other activities (school, work, or taking care of loved ones). Detroit resident Rhonda raises these issues when she points out that “water should be a human right.”

Lack of water limits individual and community access to hygiene and sanitation. And much has been studied and written about both nationally and globally about the costs of lack of sanitation and hygiene. Lack of wastewater disposal and treatment and ability to maintain personal hygiene can negatively impact children’s experiences at school and adult experiences at work (or gaining employment). Furthermore, not having access to hygiene can increase personal stigma and powerlessness -- which exacerbates economic and health inequalities. Some residents have remarked that homes with blue marks imprinted on the front of their sidewalks indicating that water has been shut off in that home, highlights shame for the homeowner and targets the home for potential foreclosure and crime. Individuals have to contend with how to clean their own human waste, hands and how not to spread to others. Girls and women have to deal with additional stigma of how to deal with menstrual blood. Residents with physical disabilities or elders have more barriers added to their everyday lives accessing water.

Local residents have also indicated that if kids slipped up and revealed that they didn’t have water in their homes they would be picked up by child protective services. One Detroit resident talked about increasing number of middle school students who were showing up at school without clean clothes or bodies—who are now taking showers at school but not saying anything about water being shut off in their homes.

Since 2005, Detroit has linked unpaid water and sewage bills to property taxes.29 (See Figures 3 and 4). When residents and homeowners are unable to pay their water bill and property taxes this then leads to foreclosures and “abandonment.” Sometimes overdue water bills are linked to absentee landlords and renters face the negative consequences. In other instances, reports have found that some of the foreclosed, abandoned and unoccupied homes continue to have running water (with water faucets left on) with bills owed to DWSD ranging from $5000 to $10, 000.30 One third of “DWSD water is unmetered from leaks and running water in abandoned buildings.”31 Researchers with a coalition of community members (We The People of Detroit Community Research Collective) have found that in 2014, 11,979 foreclosed properties had water bills added to property taxes.32

In February and March 2017, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (under the Great Lakes Water Authority) issued “boil water” advisories to two Detroit enclaves (Hamtramck and Highland Park) stating an “equipment malfunction” caused by water pressure. This “equipment malfunction” has the potential to result in bacterial contamination. A similar advisory regarding the use of tap water was made by the Detroit Medical Center (downtown Detroit) to its employees. As of March 3, 2017, this advisory has been lifted.33

Housing and Health

WHAT WAS INITIALLY EXPERIENCED as “redlining”34 and blockbusting in the housing and lending markets in 1940s and 1950s, by Black Detroit residents, the 1990s and 2000s offered subprime, predatory, or “ghetto loans” to residents remaining in these redlined areas (later broadened to include more women, seniors, and other racial/ ethnic communities). The later practice has been referred to as “reverse redlining.”

Later on in the 1990s and 2000s, larger private banks and investment companies with the assistance of government deregulation and lack of oversight—brought new forms of profitable discrimination and re-segregation in Detroit.35 Journalist and activist, Laura Gottesdiener has pointed out that companies like Wells Fargo would often hire and incentivize Black salespeople to go to Black churches (already established redlined zip codes) to aggressively recruit clients to sign up for predatory risky “ghetto loans.”36 From 2005-2015, Detroit experienced nearly 140,000 foreclosures, or 1 out of 3 homes, in the city.37

Forced geographical and racial segregation simultaneously increases community isolation, exclusion from quality social services, and surveillance/policing by the criminal justice system. Isolation, systemic indifference, surveillance and policing deepen individual and community poverty. In addition to the stripping away of social safety net and infrastructure, forcibly segregated communities are divested of wealth and opportunity building resources of quality reliable transportation, housing and educational security, meaningful work opportunities, and nutritious food. For instance, 93% of the housing stock in Detroit was built before 1978 and these homes can expose or poison the city’s children to lead based paints and dust. (The Affordable Care Act now covers lead testing for children in the Medicaid and Women Infants and Children (WIC) program as a preventative service.38

Detroit’s residential and commercial landscape (such as homes, buildings and lots) has often been described in terms such as vacancy, abandonment, and blight. All of these phenomena have been marked by systemic forces that have pushed people out of homes, communities, schools and work—such as foreclosures, subprime or predatory lending, reverse redlining, redlining, absentee landlords, the flight of capital and work, mass incarceration, the dismantling of social services, and racial and class injustice. This kind of turbulent and insecure relation to one’s home, place, neighborhood and place of safety and rest takes an extraordinary toll on one’s well-being.

In addition to redlining another practice of the “housing disassembly line”—where the housing industry contractors overproduced and supplied new houses in the suburbs—pulled more and more people away from city homes into the suburbs and new neighborhoods.39 These practices contributed to the increases in vacant structures, high neighborhood turnover rates, reductions in property value in the city, and reductions in the property and income tax base.40

Additionally, urban studies scholar, Margaret Dewar, has pointed out that “residential abandonment” since the 1970s has been most acutely felt in US cities that have high concentrations of racially and ethnically marginalized and low-income residents. In addition to “residential abandonment” cities like Detroit have experienced relinquishment of commercial buildings and land in its downtown neighborhoods. These concentrations of vacant structures and land coincide with what many urban researchers have noted about postWorld War II cities (particularly in the Midwest and Northeast): depopulation, loss of work, racial divisions, disinvestment and deindustrialization.

Nine of fifty US cities were depopulated in every decade between 1950 and 2000—and Detroit made this list. Detroit lost more than 50% of its population between 1950 and 2010. (In 1950, with a population of 2 million, Detroit was the 4th largest US city and by 2010 had lost 61% of its total population).41 Furthermore, while Detroit spans about 139 square miles, about 18% of its area was vacant with 90,000 vacant lots in 2001. More recent figures, provided by urban studies scholar, George Galaster, states that 30% of the city is comprised of either vacant land or buildings—where homes cannot be brought back to the “housing stock” due to its condition.

In both 2007 and 2008, Detroit topped the rates of national home foreclosures of US cities.42 In 2008 alone, Detroit experienced about 94,000 property-tax foreclosures.43 In the first quarter of 2009, one out of 275 housing units in Detroit faced foreclosures. By 2010 Detroit had a housing vacancy rate of 23%.44 Laura Gottesdiener has argued that the loss of 25% of Detroit’s population between 2000-2010 wasn’t entirely a volunteer migration. This particular phase of depopulation was driven by bank foreclosures that piggybacked on “subprime” loans and high-risk financial instruments. She points out that 100,000 homes were foreclosed upon in Detroit between 2000 and 2012 and that from 2004–2006, “73% of the new mortgages in the city were predatory loans, compared to 20% nationally.”45 With more and more foreclosures, residential property values declined (in many instances residents “owed more than 20 times what their property was worth”), which in turn catalyzed more foreclosures.

Another report point to the increased “return on investment” for Wayne County due to increasing numbers of auctions due to foreclosures in the city. A recent report has shown that since 2002, Wayne County has foreclosed upon over 160,000 properties. Foreclosures and auctions now have become a way for counties that were financially struggling earlier due to declining property tax revenues to now balance their budgets. According to the report, counties such as Wayne County borrow from banks/investors at low interest rates and charge administrative fees and high interest on back taxes owed.46 Some have raised concerns about inflated property taxes directed towards lower value assessed properties in Detroit. For example, Bernadette Atuahene has argued that over assessed property taxes in Detroit have resulted in illegal foreclosures in the city.47

Foreclosures also cost the local government “…$220 million in lost property revenues and as much as $2 billion in government-absorbed foreclosure costs.”44 The costs associated with foreclosures and new waves of depopulation have accelerated the decline in municipal revenues and ability to provide consistent public services (for instance: fire, police, and garbage collection) for residents living in effected areas. And, the remaining impoverished residents continue to have to deal with increased utility rates (for water and sewage) and due to a “shrinking city” trying to cope with deteriorating infrastructure. Homeowners also have had to deal with over-assessments on their property-taxes on their undervalued homes and have been subjected to foreclosures.

Researchers have noted that the recent housing bubble (1996-2006), the current reincarnation of predatory lending (in the late 1990s and early 2000s), ongoing deregulation policy implementation (particularly under Regan and Clinton)48 and the Great Recession affected Detroit earlier and harder than other regions.

For instance, in the 1960s Detroit neighborhoods began to face high rates of abandonment and foreclosures when many African American homeowners couldn’t meet their mortgage payments on their FHA (Federal Housing Administration) insured mortgages. Many of these homes required repairs that the owners could not afford and were appraised and underwritten under fraudulent conditions.49 Additionally, journalist John Gallagher has pointed out that the lower “quality of housing stock” wooden houses rapidly produced for lower income southern and Appalachian migrants hard a much harder time keeping up with humidity of the area and high rates of basement flooding due to a “high water table.”50 Decades of redlining policies coupled with lower quality houses have confined and contained low-income communities of color in the city.

In the 1990s, what has been described as one of Michigan’s “largest securities fraud case,” thousands of residential foreclosures and “blight” came about in the city due to the bankruptcy of RIMPCO Financial Corporation that generated high-risk mortgages to Detroiters.51

Homeowners who left the city for the suburbs often sell their property to local landlords who minimally improved or maintained the property for city renters. When renters also began to move on from the city or stopped renting local landlords began to abandon properties. In many recent cases, new renters often inherited the unpaid water bills of their absentee landlords. Detroiters, who inherited property from elderly relatives did the same when they couldn’t rent, sell or keep up with maintaining the property.52 In other instances speculators and landlords (including large banks and businesses) have practiced “blight violations” and have not paid property taxes.53

Maurice Cox, Detroit’s new Director of Planning and Development, has recently raised important questions about Detroit’s blight, vacant land and buildings. He points out that “…the question of blight is a really complex one. One person’s blight is another’s rehabilitated building. We have to very intentionally towards the preservations on not just single buildings … but of entire neighborhoods at the same time.” Cox has pointed out that a large part of the effort at restoring Detroit’s neighborhoods (such as increasing quality affordable housing; improving safety, security and lighting; having an eclectic mix of single and multi-family housing; and mix use spaces) for those outside of the downtown and midtown, in equitable and new ways, involves restoring neighborhood health to Detroiters who have had to weather through historical waves of turbulent times.

Housing & Health

The place of one’s dwelling embodies emotion, policy, and systems of privilege, equity or inequity. For instance: (1) the physical space of a home could provide a person an emotional, psychological and physical sense of safety, security, intimacy, shame, self-worth, and control both from outsiders and insiders; (2) the physical space of one’s home is marked by the quality and property value of the physical structure and foundation; the presence or absence of mold, infestation, sanitation, water, clean water, lead paint, etc.; or the need for home repairs; (3) one’s home is impacted by the quality and safety of your immediate neighborhood, the people and structures around you; the availability of walking areas, streets, street lights, amenities, public services, parks, grocery stores, schools, businesses in the area, garbage collection and sanitation services and degree of racial and class segregation; and (4) one’s home is the historical product of economic, political and social policies in the housing and health sectors—that produces intergenerational wealth and well-being.54

With higher numbers/rates of vacancy and abandonment residents are forced to face isolation, fear and anxiety for one’s safety, stigma and helplessness, and loss of neighborly interaction and ties. Studies have indicated that vacant and abandoned neighborhoods produce spaces where there is elevated risk of fires and property damage, increase in stigmatized unauthorized economies, fewer people taking walks, dumping, and buildup of trash and animals searching trash.55

Added to this scenario of isolation is increased taxation on utilities such as sewage and water services that has a declining infrastructure and severely ineffective city services (garbage collection, street lights, businesses, schools). The impact of this kind of abandonment can be severely troubling and stressful for the mental and physical health of individuals that have to stay on.56 In addition to losing property values and individual credit worthiness, local economies and governments face costs associated with maintaining or not maintaining the properties and neighborhood that have stopped being a reliable source of tax revenue.

The literature on foreclosures and health points to the vicious cycle of how (1) poor health can accelerate foreclosures; (2) foreclosures increase the risk of poor (mental and physical) health –particularly in low-income, vulnerable, communities of color that are juggling various financial obligations,57 and (3) economic downturns and financial crises are associated with austerity programs where social services and safety-net programs are cut. Robust literature exists linking negative health outcomes to foreclosures, particularly in high foreclosed upon areas. A spike in foreclosures has been associated with higher than usual ER use and unscheduled hospital visits.58 This spike builds upon histories of racial and class. Subsequently, the devastating stress of defaulting and loss of one’s home (often associated with feelings of shame, poor character and stigma— where home and home ownership can mean a lot more than the “American Dream”) has “potential to exacerbate existing social disparities in mental health.”59 60

Medicaid Expansion and Traditional Medicaid

Like many Republican dominated state legislatures, when Michigan Governor Snyder proposed Medicaid Expansion, in April 2013, the Michigan legislature did not initially appear to be supportive. The legislature softened their opposition to federal funds as long as Michigan’s Medicaid Expansion population would show “some skin in their game,"61 meet “free-market” conditions, and demonstrate savings and revenue for the Michigan state budget.

On April 1, 2014 Michiganders started enrolling for Medicaid Expansion, the Healthy Michigan Plan (see Figure 5), under the ACA. Michigan Governor Snyder signed the Healthy Michigan Plan into law on September 16, 2013.62 Michigan applied for a Section 1115 waiver to the federal government (Secretary of HHS) for a demonstration/pilot project that would “promote the objectives of the Medicaid and CHIP programs” under the ACA Medicaid expansion, instead of going for a straightforward ACA Medicaid expansion.

Healthy Michigan under the ACA provided an opportunity for the state to also cover newly eligible low-income able-bodied adults without children, who were not-pregnant, 19-64 years old, and between 0—138% FPL.63 Prior to the ACA traditional Medicaid program provided little or no coverage to this population. Michigan’s Medicaid Expansion program expanded through a Section 1115 demonstration program (or waiver) that replaced and updated an existing waiver program called the “Medicaid Nonpregnant Childless Adult Adults Waiver” or the “Adults Benefits Waiver (ABW).”64

Nearly 2/3rds of Detroiters have incomes below 138% of the FPL (or a one-person household earns $16,643 annually for Medicaid eligibility in 2017).65 Increased enrollment in Medicaid has been associated with economic downturns, decline in income, and loss of employment. The Medicaid Program (enacted under Title XIX of the Social Security Act) was created simultaneously with the Medicare Program in 1965. Medicaid is a jointly funded federal-state program and was designed to provide healthcare coverage primarily for certain categories of individuals with low-income and limited resources—initially for families with dependents and blind and disabled individuals receiving cash assistance. Since its passage many other categories of persons (at varying income levels) have qualified for it, such as children, parents, pregnant women, and “aged, blind and disabled” individuals.

The federal government establishes general guidelines and minimum standards and states establish their own criteria for benefits, eligibility and what is paid to providers.66 The federal government matches every dollar that the state invests in Michigan. Michigan implemented its Medicaid program in 1966, and currently the federal share of funds is at 65.60% and Michigan’s share is 34.4%.67 So for every dollar the State of Michigan puts in for its traditional Medicaid program, the federal government will match it with $1.91.68

The federal matching rate for Medicaid Expansion under the ACA is more generous than traditional Medicaid. For newly eligible Medicaid enrollees, the federal government would cover 100% of the share from 2014 to 2016. In 2017, the federal government would drop its share to 95%, 94% in 2018, 93% for 2019 and from 2020 and beyond it would cover 90% of the cost.69

Prior to the passage of the ACA, Michigan Medicaid primarily covered children, pregnant women, and some seniors, parents and individuals with disabilities. Of the 1.9 million eligible Michiganders, almost 1,050,000 were under 21 years and almost 413, 600 were seniors and people with disabilities. Some have pointed out that Michigan’s eligibility standards adopted some of the lowest income levels in the Midwest. For example, single parents were covered at 50% of the Federal Poverty Level ($5, 418 annually for an individual) and childfree adults were covered at 35% of the Federal Poverty Level (just under $3,800 per year for an individual).

Medicaid in Michigan has been (and continues to be) a critical safety-net program for (1) low-income seniors and certain individuals with disabilities—in the payments to nursing homes and other institutionalized care (Medicaid paid for 70% of nursing home care); (2) children’s healthcare—particularly in areas dealing with asthma and dental disease (3) maternity care—in 2010, Medicaid paid for more than half the births in Michigan.70 In many ways Medicaid in Michigan is the largest public payer of healthcare and for long term care.

Children in Michigan have also benefits from an upgraded Medicaid program—State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). CHIP builds upon the traditional Medicaid program and was created in 1997 as a federal-state partnership to cover children 19 years and under in families with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid and too low to afford private insurance. The federal matching rate for CHIP is higher than traditional Medicaid. The implementation of CHIP has reduced national rates of uninsurance for children from 25% (in 1997) to 13% (in 2012). In Michigan, children in families up to 200% of the Federal Poverty Level are covered through a combination of Michigan’s CHIP program (or MIChild) and Medicaid (Healthy Kids).71 While MIChild has been seen as providing very good healthcare coverage, Healthy Kids has come under some criticism in cities such as Detroit where access to kids dental care has not been limited.72 CHIP was reauthorized in 2009 under the Obama administration (as the legislation known as CHIPRA) and under the ACA till 2019.

Skin in the Game

Some of Healthy Michigan’s “cost-sharing” requirements include: (1) enrollees make income based premium contributions (2% income for those between 100-138%); pay some amount of co-pay and co-insurance; and make income based contributions to Health Savings Accounts required for 100-138%. Evidence of “personal responsibility” could reduce some of these cost-sharing requirements such as co-pays.

The official goals of the demonstration project include whether or not there has been: (1) reductions in the number of uninsured in Michigan; (2) the encouragement of “personal responsibility” among enrollees by the promotion of “healthy behaviors” to result in healthy outcomes;73 (3) improvements in access to healthcare; (4) reductions of “uncompensated care” and subsequently Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments to hospitals; (5) an impact on premium rates and rate filings; and (6) improvements in “effectiveness and performance” of the Medicaid program. In order to evaluate these goals certain government departments (Department of Community Health, Dept. of Insurance and Finance) as well as universities (UM Institute of Health Policy and Innovation) have been tasked to perform evaluations.

The emphasis on “personal responsibility” only by people who have been systematically disadvantaged by corporate and government policies is particularly troubling. While being accountable for one’s own actions or getting baseline clinical tests for your ongoing healthcare or even the possibility of “shared responsibility” can be helpful and fair—it is disconcerting that only low to moderate-income people and/or ordinary Americans are scapegoated to maintain a healthcare system that often avoids financial transparency and accountability.

Personal responsibility is variously referred to as “cost-sharing” or “skin-in-the-game” by some policy makers and follows what private insurance companies have long practiced before the ACA. This includes various patient fee deductions, such as: paying a percentage of income for premiums, co-pays, deductibles and co-insurance; and taking health risk surveys, demonstrating healthy behaviors (reducing one’s weight or smoking) and taking annual health exams to qualify for reductions in cost sharing. Another consequence patients face is disenrollment if one fails to pay premiums and bar them from enrolling the next six months. Significant research has shown that such extra fees and costs are barriers and deterrents for many low-income people to maintain health coverage.74 However, the short-term goal of cost-containment and profit is met for the insurance companies and the payer (or the state using public funds). Through waivers many state legislatures and governors have altered and weakened federal Medicaid rules to use public funds to purchase private-sector products (such as through the Marketplace) that may be less rich in benefits and shift more financial liability onto vulnerable individuals.

Policy makers and state/city officials view the infusion of these federal funds as a much “needed economic stimulus to the state” by directly and indirectly benefitting the Michigan economy.75 Directly by paying: hospitals, physicians, universities, clinics, insurance companies, and pharmaceutical industry (or what some call the “Eds, Meds & Feds” approach to economic revitalization of distressed cities).76 The argument is that as certain industries (such as auto and manufacturing) have left cities like Detroit other large employers have taken root and serve as anchors for the city. These new institutions are clinical and educational centers such as hospitals and universities who indirectly and directly receive federal dollars. Medicaid expansion and other provisions of the ACA are key ways in which federal dollars can be infused into municipal and state governments, hospital systems and institutions of higher education.

Studies also project that expansion will reduce state spending on “uncompensated care” programs and reduce “cost-shifting” practices by hospitals and the insurance industry on to individuals and employers (by raising premium rates).77

Even though the Healthy Michigan program was approved until December 31, 2018—Michigan had to apply for and got a second waiver approved by December 31, 2015. This second waiver would continue the Medicaid expansion program but would heighten more “free market” and “skin-inthe-game” conditions. The federal government had to approve Michigan’s plan to ask those enrollees, who have been on Medicaid for 48 months, between 100 -138%FPL to either purchase coverage from the health insurance exchange or “marketplace” or remain in Medicaid with increased cost-sharing (contribute up to 7% of income to premiums and increase HSA contributions to 3.5% of income).78 Reports suggest that about 15-18% of the expansion population (on a monthly basis) have incomes above 100% of the FPL.79 If this second waiver was not approved Medicaid coverage for the expansion population will be terminated on April 30, 2016 and 600,000 Michiganders would have been at risk of losing health coverage through Medicaid expansion.

As of March 7, 2017, the Healthy Michigan Plan has 651,508 enrollees. The majority of enrollees (over 500, 000) are at or below 100% of the federal poverty level (or an individual whose income is $12, 060 or less in 2017).

The Private Option (or the Marketplace)

A central goal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed on March 23, 2010, was to increase access to affordable and quality health coverage. This objective relied on two key routes (1) Medicaid Expansion and (2) the so called “private option” or the “Health Insurance Marketplace.”80 Michiganders began to enroll in the “Marketplace” on October 1, 2013 for coverage beginning on Jan 1, 2014. As of December 2016, 313,000 Michigan residents had private health insurance through the Marketplace.

It was estimated that over 71% of the uninsured in Michigan would be eligible for Medicaid or the “private option” subsidies. And, based on the income demographics of Michigan’s uninsured population, was projected that Medicaid would be the primary route. A study by the Urban Institute/ RWJF estimated that Detroit would experience a 66% reduction in the uninsured by 2016. By early 2015 the Detroit Depart of Health and Wellness Promotion reported that the rate of uninsurance in Detroit was down by 50% (100,000 Detroiters were since without health insurance coverage).

According to the Health Authority (formerly Detroit Wayne County Health Authority) prior to the passage of the ACA, adult Detroiters (ages 18 -64 years) were twice as likely to be uninsured compared to other Michiganders.81

Adults in Detroit reported a higher prevalence of chronic conditions including asthma, high blood pressure, disability, activity limitation and diabetes. Infant mortality rates were twice as higher than the state indicating the convergence of multiple inequalities and related stressors of poverty such as gender, income, and race. A study by the Health Authority study pointed out that individuals making less than $20,000 reported poorer health status and Latino/as reported the worst health status (about 41% of the Latino/a community).

In addition to supporting Medicaid expansion Snyder also supported a state-run Health Insurance Marketplace (or “Marketplace”). Michigan received federal funding for planning for a statebased marketplace but this provision of the ACA was an issue that could not pass the Michigan Senate. Instead, Michigan applied and was approved for a “State-Federal Partnership Marketplace” by the US HHS on March 5, 2013.

A report by Families USA pointed out that 1 in 4 Michiganders (2.4 million people between 18-64 years) had been diagnosed with (or treated for) pre-existing conditions that could lead to denial of coverage.82 Wayne County was reported have 1.55 million people with pre-existing conditions. Nearly 50% have a medically diagnosed pre-existing condition in Michigan in the 55 to 64 year group.

The ACA’s removal of “pre-existing” conditions was coupled with the requirement that health insurance was mandatory requirement for all eligible individuals. In many ways the removal of “pre-existing” conditions eroded practices of “health status redlining” pursued by the medical underwriting industry. And, since it was mandatory, the issue of affordability was intended to be addressed by subsidies for those who fell between 139 to 400% FPL. On June 2015, the US Supreme Court, ruled in favor of the ACA subsidies, that enrollees in states (like Michigan) who have a federally run “Marketplace” qualified for these subsidies or premium tax credits.83 Had the US Supreme Court ruled against the ACA subsidies in King versus Burwell, 228,000 Michiganders would have been at risk of losing their subsidies and premiums could have gone up by 294%.84

Conclusion

CLOSE TO A MILLION PEOPLE in Michigan depend upon the Affordable Care Act for health insurance with significant financing from the federal government. For instance, the Healthy Michigan Plan, costing $3.6 billion for FY 2016, was primarily financed by the federal government. According a recent study, ongoing federal funding for Michigan’s Medicaid Expansion could benefit the state by (1) reducing annual expenditures for prison health programs and mental health services by $235 million; (2) increase jobs in the healthcare, manufacturing and retail sectors and fuel increases in income and sales tax revenues linked to those jobs; and (3) redirect low-income consumer spending into food, transportation and housing (instead of healthcare expenses).

Other reports have found that hospitals have experienced declines in unpaid hospital bills from $1.1 billion (2013) to $913.5 million (2014)—and much of this has been attributed to the increase in health insurance coverage via Medicaid Expansion and the Marketplace, the provision of subsides/ tax credits, and removal of pre-existing conditions. Detroit and Wayne County residents have some of the highest enrollments in the Healthy Michigan (175,000 in Wayne County enrolled in Healthy Michigan Plan).85 The net effect on the state budget has been estimated to be $553.9 million in FY 2016.

If repealed or replaced close to a million people could lose health coverage. Michigan stands to lose $3.4 billion in federal funds and cuts in jobs in hospitals, clinics, construction and retail associated with the Healthy Michigan Plan. The state also stands to lose tax revenue from insurance companies and hospitals (estimated at $194 million in FY 2016).86 The defunding of Planned Parenthood will disproportionately impact low-income women of color in Detroit and severely effect women’s health services (including cancer, HIV, and STI screenings and prevention, reproductive health services, free birth control, and LGBT health services).87 65% of Planned Parenthood patients in Michigan are low-income.

While Medicaid Expansion (and the private option of the ACA) does provide increased coverage and access to much needed acute and preventative clinical care and relief to state and hospital budgets it is primarily conceptualized as an austerity-based biomedically oriented and financed response to community well-being. The plan exists without a robust relationship to social services that can address health impacted by the material conditions of vulnerable Detroiters.

With an expansive understanding of health and the places where well-being flourishes, and modification of financing models, road maps to health equity can gain more inroads. Here are some promising experiments:

First, while the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) compensation policies continues to disregard critical nonclinical resources/ services as contributing towards health or the care giving and labor of non-clinicians as not reimbursable within the clinical hierarchy, many states and organizations are revisiting the important relationship between housing and health. For example, states and various organizations have developed and implemented “supportive housing” projects for chronically homeless persons.

Studies have pointed out that chronically homeless88 people are more likely have high rates of uninsurance, have co-occurring complex mental and physical health conditions, visit ERs and have longer hospitals stays (if admitted). The ACA Medicaid expansion offers an opportunity for states and local governments to further this link. Examples include: New York Medicaid utilizing, $260 million state-Medicaid dollars to create new housing units, rental subsidies and other housing pilot projects for homeless Medicaid enrollees; Massachusetts launching housing pilot programs in 2014 for chronically homeless persons through “Pay for Success” contracts leveraging private and philanthropic funds for Medicaid enrollees; and more closer to home in Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti similar efforts have been initiated with the assistance of the Corporation for Supportive Housing and the Social Innovation Fund (a White House initiative).89

Secondly, the city of Detroit’s commissioned report, the Blue Ribbon Panel, recommended that the city look into water and sanitation assistance program equivalent to the federal low-income home energy assistance program (LIHEAP). This would be another concurrent policy that could begin to address the water and housing health crisis in the city.

And, last, the Trump administration’s “repeal, replace and rebranding” or Trumpcare guarantees more austerity and “personal responsibility” from marginalized communities. This includes a much harsher version of Medicaid Expansion emerging in the form of block grants, defunding of Planned Parenthood, uncertainty with the private option and social services. This poses a timely issue for multiple stakeholders and community members to collaborate in solidarity with all Detroit residents.

This paper concludes with next questions that could be further examined and explored.

- 2Paul E Farmer, Bruce Nizeye, Sara Stulac, and Salmaan Keshavjee: Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine, PLoS Med., Oct. 3(10), 2006.

- 3Elizabeth H. Bradley and Lauren A. Taylor: The American Health Care Paradox: Why Spending More is Getting Us Less, Public Affairs, New York, 2015.

- 4A New Way to Talk about the Social Determinants of Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Carger, E and Westen, D, Jan. 1, 2010.

- 5Anthropology For The City: Krysta Ryzewski and Andrew Newman, March 23, 2016; and Shea Howell: “Separate and Unequal,” We the people of Detroit, August 14, 2016.

- 6The City of Detroit Blue Ribbon Panel on Affordability, Final Report,” Prepared by Galardi Rothstein Group, Pg. 11, Feb. 3, 2016; Karen Bouffard, The Detroit News, Sept.17, 2015 and Mapping The Water Crisis: The Dismantling of African American Neighborhoods in Detroit, We the People of Detroit, Vol. 1, 2016.

- 7Heather Thompson: Unmaking the Motor City in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” Journal of Law and Society, December 2014.

- 8Thomas J. Sugrue: The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton University Press, 2014.

- 9In March 2013 Michigan Governor Rick Snyder appointed Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr to take control of city finances and operations. Orr subsequently authorized Detroit’s bankruptcy filing on July 18, 2013 and negotiated with major creditors to formally clear the city from bankruptcy in December 2014; Robert Reich: The Bankruptcy of Detroit and the Division of America,” robertreich.org, Sept. 5, 2014.

- 12Shea Howell: “Thinking for Ourselves: Council Resolves on Water,” Detroiters Resisting Emergency Management, May 16, 2015.

- 13Reports indicate that from Jan. 1, 2014 to Jan. 31, 2015—35,000 households and 96,000 individuals had lost water and sewage services for nonpayment. As of February 2015, approximately 147,000 residential customers were at risk for losing water and sewerage services for nonpayment. They were 60 days past due and owed an average of $664 on their bills (Food and Water Watch: “Detroit Needs a Water Affordability Plan,” May 2015). Under the Emergency Manager the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) had moved to shut off water to 150, 000 households. Private contractors, such as Homrich Wrecking subcontracted with the DWSD to turn off water—often at the rate of 3000 households/week (Dean, 17 July, 2014).

- 14In 2014, the Detroit People’s Water Board organized to get the United Nations, the National Nurse’s United and the Netroots Conference to shine a light on mass water shutoffs in Detroit. A statement released by the United Nations (20 October, 2014) reported that after they spoke with individuals with chronic illness and disabilities, low-income single mothers and older persons, that in 2014 at least 27, 000 households had water and sewerage services disconnected. Access to clean water as a basic human right, demanded by many Detroit residents and resolutions from the United Nations General Assembly, placed a symbolic political responsibility on Detroit’s City Council not to restrict access to affordable clean water to residents. UN resolutions are not legally enforceable and similar to the UN recognized issue of the right to sanitation. The Detroit People’s Water Board is a coalition of organizations (unions, community groups, religious groups) “representing issues pertaining to labor, the environment, social justice and conservation.”

- 15The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) played (and continues to play) a central role during and after the bankruptcy process. The DWSD serves more than 3 million people or roughly 40% of Michigan’s population (including the city and SE Michigan). In 2014, DSWD began mass water shut offs of 30,064 accounts. But despite the 15-day moratorium in July 2014 (due to media attention, community outrage and litigation), another round of water shut offs followed -- 15,461 in in 2015 and 30, 496 in 2016. This information is discussed in The Detroit News here http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2017/07/26/det…

- 16On Tuesday May 25, 2015, the Detroit Water & Sewerage Department (DWSD) shut off water for another 1,000 Detroit households with an additional 25,000 homes slated for future shut offs. The DWSD considered these accounts to be delinquent and went ahead with the shut offs despite a May 12 resolution passed by the Detroit City Council calling for a moratorium. City Council agreed to a moratorium until the DWSD could evaluate the existing plan and consider implementing the “Water Affordability Plan”

- 17The Grand Bargain was negotiated between the Emergency Manager, federal bankruptcy judge, the Michigan Legislature and Governor, private foundations, city officials, creditors, bond insurers, current employee and retiree unions and representatives (in regards to pensions, retirement and healthcare benefits and union contracts).

- 18Rick Cohen: “Water Crisis in Detroit: Who’s Being Shut Off and Who’s Not,” Nonprofit Quarterly, 30 June, 2014.

- 19Ibid.

- 20Joel Kurth: “Detroit Hits Residents with water shut offs as businesses slide,” The Detroit News, April 1, 2016.20 Tyler Van Dyke: “Detroit to resume Water Shutoffs this month,” May 9, 2015, www.wsws.org.

- 21The City of Detroit Blue Ribbon Panel on Affordability, Final Report,” Prepared by Galardi Rothstein Group, Pg. 28, Feb. 3, 2016; Karen Bouffard, The Detroit News, Sept.17, 2015.

- 22Rachel Butts and Stephen Gasteyer: “More Cost Per Drop: Water Rates, Structural Inequality, and Race in the United States—The Case of Michigan,” Environmental Practice, 13(4), Dec. 2011.

- 23Wallace C. Turbeville, “The Detroit Bankruptcy,” pg.5, Demos, November, 2013. Turbeville’s analysis states that the healthcare expenses accounted for annual increases of 3.25%, which falls below 4% increases in healthcare costs experienced nationwide. Furthermore, Turbeville adds that “healthcare costs may be relatively lower as a result of the ACA.” (25)

- 24Jerry White, “Detroit Officials Defend Water Shut Offs,” wsws.org, Sept. 25, 2014.

- 25Another report, DWSD Equity Analysis prepared by The Foster Group (May 1, 2015) estimates this figure to be $6.4 billion.

- 26Lack of clean water, hygiene and sanitation, can increase communicable diseases such as: diarrhea, trachoma, malaria, asthma, gastroenteritis, hookworm, salmonella, and infective hepatitis—often diseases associated with unsafe water.

- 27Laura Gottesdiener: “Detroit Is Ground Zero in the New Fight for Water Rights,” The Nation, July 15, 2015

- 28FAQs regarding the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department Tax Roll Program.

- 29Joel Kurth, “Detroit’s blight tied to unpaid water bills,” The Detroit News, Sept. 12, 2014.

- 30Detroiters Resisting Emergency Management (DREM) website.

- 31https://wethepeopleofdetroit.com/communityresearch/water/

- 32http://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/detroit/2017/03/02/boil-…

- 33In the 1940s and 1950s, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), and to some degree private “loan sharks” and private banks (aided by the property insurance industry underwriting), structured patterns of lending and housing discrimination whereby low-income/ applicants of color were either denied credit or steered into economically, racial and ethnically homogeneous neighborhoods and lower quality housing.

- 34Benjamin Howell, “Exploiting Race and Space: Concentrated Subprime Lending as Housing Discrimination,” California Law Review, Vol. 94, Issue 1, January 2006.

- 35“Lost Ground, 2011: Disparities in Mortgage Lending and Foreclosures,” Center For Responsible Lending, November, 2011; Laura Gottesdiener, A Dream Foreclosed: Black America and the Fight For A Place To Call Home, Zuccotti Park Press, 2013.

- 36See Joel Kurth and Christine MacDonald, “Volume of Abandoned Homes ‘Absolutely Terrifying,’” Detroit News, May 14, 2015.

- 37Heather A. Moody, et al: “The Relationship of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Differences and Racial Residential Segregation to Childhood Blood Lead Levels in Metropolitan Detroit,” Journal of Urban Health, 93:5, October 2016; Child Lead Poisoning Elimination Board, November 2016; https://www.michigan.gov/documents/snyder/CLPEB_Report--Final_542618_7….

- 38Galaster notes that every year since the 1950s the housing industry produced 10,000 new homes in an unplanned, unregulated manner in excess of actual number of households and demand. George Galaster: Driving Detroit, 2012.

- 39Galaster points out that property values in the city have gone down by 79% since the 1950s. And, that since 1972 the value of income taxes collected dropped by ¾.

- 40The City After Abandonment, ed., Margaret Dewar and June Manning Thomas, pg. 4, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. The authors define abandonment “of a property as occurring when the owner stops taking responsibility for it. ‘Neighborhood abandonment’ or ‘city abandonment’ refers to places where large levels of population and household loss have led to large amounts of property abandonment, manifested in a high percentage of vacant houses, buildings, lots and/or blocks, which jeopardize the quality of life for remaining residents and businesses.” Colin Gordon: “Blighting The Way: Urban Renewal, Economic Development, and the Elusive Definition of Blight, “Fordham Urban law Journal, Vol 31, Issue 2, 2003.

- 41Ibid, page 195.

- 42“Activists, neighbors hope to block Detroiter’s eviction,” Bill Laitner, Detroit Free Press, Aug. 14, 2015.

- 43Ibid, pg. 195

- 44Laura Gottesdiener, A Dream Foreclosed: Black America and the Fight For A Place To Call Home, 71, Zuccotti Park Press, 2013.

- 45See, "Sorry we foreclosed your home. But thanks for fixing our budget," Joel Kurth, Mike Wilkinson, Laura Herberg, Bridge Magazine, June 6, 2017.

- 46See "Detroit's Tax Foreclosures Indefensible," Bernadette Atuahene, Detroit Free Press, September 1, 2016.)

- 47Ibid, pg. 73. Other sources report that between 2009-2013, over 70,500 Detroit properties have been foreclosed, resulting in $744.8M in lost city property taxes (Detroit Blight Removal Task Force Plan).

- 48For instance the deregulation of the savings and loans industry under Ronald Regan and the banking industry under Bill Clinton.

- 49Dewar, 5.

- 50John Gallagher: Reimagining Detroit: Opportunities for Redefining an American City, pg. 24-25, Way

- 51Ibid, pg.5 and http://www.metrotimes.com/detroit/all-fall-down/Content?oid=2188200.

- 52Detroit has a residential vacancy rate of 27.8 percent and 22.8% poverty rate (2010) and has gone through 55,000 foreclosures since 2005. The city experienced another wave of foreclosures after the lifting of temporary moratoriums. (pg. 3, Dewar)

- 53http://www.crainsdetroit.com/article/20161016/NEWS/161019896/state-law-…

- 54“Where We Live Matters For Our Health: The Links between Housing and Health,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, September 2008.

- 55Jennifer Guerra: “Abandoned homes affect your health. But here’s what can help,” State of Opportunity, July 20, 2016; and the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study.

- 56“The Social Costs of Deindustrialization,” Center For Working Class Studies, Youngstown State University.

- 57Kimberly Libman: “Housing and Health: A Social Ecological Perspective on the US Foreclosure Crisis,” Housing, Theory and Society, 2012. Craig Pollack and Julia Lynch: “Health Status of People Undergoing Foreclosures in Philadelphia,” American Journal of Public Health, 99:10, October 2009.

- 58Janet Currie & Erdal Tekin: “Is there a Link between foreclosures and health?,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 17310, August 2011.

- 59Jason Houle: “Mental Health in the Foreclosure crisis,” Social Science and Medicine, 118, 2014.

- 60Amy Schultz, et al: “Discrimination, Symptoms of Depression and Self-Rated Health Among African-American Women in Detroit: Results From A Longitudinal Study,” American Journal of Public Health, 96:7, 2006; R. Morello-Frosch: “Understanding The Cumulative Impacts of Inequality in Environmental Health,” Health Affairs, 30:5, 2011; Sepideh Modrek, et al: “A Review of Health Consequences of Recessions International and US and a synthesis of the US Response during the Great Recession,” Public Health Reviews, 35:1, 2013.

- 61“Michigan’s Medicaid Expansion Experiences: A presentation to the Civic Federation and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago,” Christopher Harkins, Director, Office of Health and Human Services, Michigan State Budget Office, April 4, 2016.

- 62On December 30, 2013 Michigan obtained approval from the CMS for the “Healthy Michigan” Plan. The Public Health Act 107 of 2013 established the Health Michigan Plan. “Approved Demonstrations Offer Lessons for States Seeking to Expand Medicaid Through Waivers,” Jesse Cross-Call and Judith Solomon, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Aug.20, 2014.

- 63This includes childfree adults between 0-138%, childfree adults who were covered at 35% (with asset limits up to $3000) and working (64%) and non-working parents (37%).

- 64In the ABW program able-bodied childfree adults could be Medicaid eligible if they were at or below 35% FPL.

- 65“The ACA and America’s Cities,” the Urban Institute/RWJF, June 2014; “Why the ACA Matters for Women: Improving Healthcare for Women of Color,” National Partnership for Women and Families, Sept. 2014.

- 66It is overseen by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which is located within Health and Human Services (HHS).

- 67Ibid, “Reinventing Michigan’s Health Care System,” Submitted to CMS by Governor Rick Snyder, 24 January 2014.

- 68“Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier,” SY 2016, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015.

- 69The ACA initially required all states to expand Medicaid coverage to individuals with incomes at or below 138% FPL. The US Supreme Court, in June 2012, ruled that Medicaid expansion would be left up to the states and thus optional.

- 70Jan Hudson: “Understanding Medicaid: Complex, Compassionate, Cost Effective,” Michigan League for Human Services, October 2011.

- 71“Michigan CHIP Fact Sheet,” National Academy for State Health Policy, 2012.

- 72Sheila Hoag & Cara Orfield: “Congressionally Mandated Evaluation of the Children’s Health Insurance Program: Michigan Case Study,” Final Report, Mathematica Policy Research and The Urban Institute, Nov.1, 2012.

- 73Healthy behaviors include: taking the annual health risk survey from the Michigan Department of Community Health—to determine “risk factors” such as substance and alcohol abuse, tobacco use, immunizations and obesity.

- 74“Medicaid Expansion, the Private Option, and Personal Responsibility Requirements: The Use of Section 1115 Waivers to Implement Medicaid Expansion Under the ACA,” Jane Wishner, John Holahan, Divvy Upadhyay and Megan McGrath, The Urban Institute and RWJF, May 2015; and “The ACA and recent Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers,” Robin Rudowitz, Samantha Artiga and MaryBeth Musumeci, The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, February 2014.

- 75Reports prepared by various policy makers and researchers report that Medicaid expansion federal funds will benefit Michigan in the following ways: (1) yield savings of $389 million through FY 2015 for the State by replacing State general revenue funds with federal funds to address mental health programs, public health programs and healthcare services for prisoners; this includes projected savings of $190 million in FY 2015 by “by transitioning enrollees in a state-funded program that provided services for the seriously mentally ill into the new adult group” and reduction in state spending of $13.2 million in FY 2015 for hospital inpatient costs for prisoners and (2) produce revenue gains of up to $26 million through FY 2015 through fees and assessments on the state’s Health Insurance Claims Assessment. Other reports foresee other benefits since the federal matching rate for Medicaid expansion is much more generous than traditional Medicaid. “States Expanding Medicaid See Significant Budget Savings and Revenue Gains,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Issue Brief, April 2015.

- 76“Eds, Meds, and the Feds: How the Federal Government Can Foster the Role of Anchor Institutions in Community Revitalization,” Tracey Ross, Center For American Progress, 2014.

- 77According to the study projected benefits include: Michigan receiving $1.4 billion in 2016, approximately 18,000 new jobs, which in turn would increase economic activity by nearly $2.1 billion in 2016. A $351 million in savings for the state in “uncompensated care” costs from 2013 to 2022. “Michigan’s Economy will Benefit from Expanding Medicaid,” Families USA and Michigan Consumers for Health Care, 2013.