As a gay Filipino American, today has meaning far beyond what I can describe here. But it’s important for me to try. October also represents the month that President Obama inaugurated Filipino American History Month with a message celebrating the myriad ways Filipino Americans have contributed to American society. October’s significance for Filipino Americans is due to the first recorded presence of Filipinos in the continental United States when, on October 18, 1587, “Luzones Indios” came ashore from Spanish galleon ships and landed at what is now Morro Bay, California. According to a 2015 article published by The Migration Information Source, Filipinos comprise the fourth largest immigrant group in the United States, accounting for 4.5 percent of the 41.3 million total immigrant population in 2013.

Beyond well-known celebrity figures of Filipino descent such as Bruno Mars and Lea Salonga, you’ll find my parents. My mother and father are the everyday face of Filipino immigration. In 1978, both immigrated to the United States and settled in Sugar Land, Texas to work as nursing supervisors. Their cross-continental movement is, to me, a byproduct of the 1965 Immigration Act that historian Catherine Ceniza Choy cites as allowing foreign nurses to settle as permanent residents, as the demand in the United States for professional nursing services increased in the late 20th Century. From my father working day shifts in emergency rooms and intensive care units to my mother covering night shifts in a psychiatric hospital and mental health clinic, they achieved something for our family that I had previously thought was only obtainable in either sleep or fantasy: the American Dream.

Beyond well-known celebrity figures of Filipino descent such as Bruno Mars and Lea Salonga, you’ll find my parents.

Despite having to take out loans to cover the costs of attending a private, liberal arts university during the 2007-2009 financial crisis, my American Dream began to form when I left that

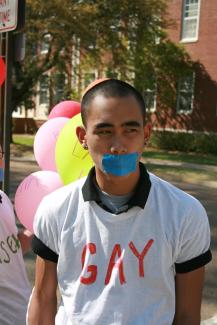

undergraduate institution to participate in the 2010 Soulforce Equality Ride, an event which laid the foundation for my current doctoral research on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) Filipino American Christians in the United States. As a traveling forum that started in 2006 to confront discrimination that LGBTQ students face at more than 100 college campuses across the United States—the majority of them being Christ-centered, conservative universities—the Equality Ride aims at reconciliation through dialogue, challenging school policies that are religious-in-intent but discriminatory-in-practice. While the main purpose of the Ride is to confront the rhetoric that sustains spiritual violence against LGBTQ students, the Equality Ride also advocated the simple message as quoted in the New Testament of the Bible in Matthew 22:39: Love your neighbor as yourself.Yet when I returned back to Texas in May 2010, my own American Dream turned into a temporary nightmare. I was still not out to my dad, when one of his colleagues mentioned an image of me (see right) published in a local newspaper engaging in a nonviolent protest at a college in Mississippi. “Isn’t this your son?” he asked. “You must be proud of him.”

I never had a Coming Out Day to my dad. The violence of not being able to control the contours of my story would only be aggravated when—despite my tears of disbelief and utter sadness falling at dinner at a public restaurant—my father tried to “pray the gay away.” This event, having occurred six years ago, is still all too real and physically palpable to me when I recall it.

But if not for these moments, I ask, when would have I mustered enough courage to come out to my dad myself? I struggle to answer this question. But looking back to my two-month journey on the Equality Ride, I can now imagine myself coming out to my dad through a courage inspired by brave LGBTQ students I met on the road. Brave students who, by the essence of their very existence as queer at conservative religious universities, engaged in the principle of nonviolent resistance to heteronormative understandings of gender and sexuality.

I never had a Coming Out Day to my dad. The violence of not being able to control the contours of my story would only be aggravated when—despite my tears of disbelief and utter sadness falling at dinner at a public restaurant—my father tried to “pray the gay away.”

In my heart, I believe in the principle of nonviolent resistance that laid the foundation for the Equality Ride bus tour; for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the U.S. struggle for civil rights; and for César Chávez and Dolores Huerta in the 1965-1970 Delano Grape Strike, leading to the formation of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW).

However, what remains silent or forgotten in popular memory of the latter movement is the crucial role played by Filipino American labor leaders like Larry Itliong. This cultural amnesia is further evidenced in the little we know regarding Filipino American labor organizing that took place at sugar plantations, canneries, and agricultural fields across the United States in the early twentieth century.

Fortunately, these stories are also beginning to “come out”, mostly through a body of academic and cultural work that writes and performs Filipino Americans into history. Reading about the valor and courage of early Filipino migrants from the likes of Fred Cordova, Dorothy Fujita-Rony, and Dawn Mabalon, I view the “roundabout” way my father learned about my gay identity as tied to the political, social, and emotional stakes that comes with speaking up and out against injustice, like early Filipino labor migrants in organizing around structural and institutional discrimination in the early twentieth century.

In the same vein of Filipino American individuals and stories that are coming out through the work of scholar activists and social justice practitioners alike, let us commemorate the bravery of little known individuals in LGBTQ history including two transgender women of color, Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, who helped put the Stonewall uprising—considered the single most important event leading to the modern gay liberation movement—on the map in June 1969.

Yes, we rightfully celebrated national marriage equality across the land last year, but in this seemingly safe atmosphere for LGBTQ Americans, let us remember Orlando. Let us also

remember 2016 is now the deadliest year on record for transgender people in the United States, with 22 transgender people murdered, nearly all of them transgender women of color. And what about transgender violence globally? Sadly, today marks the day two years ago a U.S. Marine murdered transgender Filipina Jennifer Laude in Olongapo City, Philippines. My country of heritage—and the same country that hosted the first politically motivated and received LGBTQ pride parade in Asia in 1994.It’s Filipino American History Month. It’s National Coming Out Day. It’s LGBTQ History Month. And it’s my birthday. A few of us are 28, a few a little bit older. On this day we have lot to celebrate, and we also have the responsibility to remember and commemorate. Let’s view today as an opportunity to lay the groundwork of what stories, individuals, and struggles we need to continue to come out for.

The thoughts expressed here are not necessarily that of the Division of Equity and Inclusion, the University, not official, not predictable, and not of one mind. In the spirit of the Free Speech Movement, the thoughts expressed here are those of the individual authors.

_________________________________________

Images from top