By Tom Sgouros

July 9, 2019

Across America there is a disturbing level of dissatisfaction with the banking system as we know it. Distrust of finance has a long history in the United States, but it is not beyond comprehension to imagine it related to lingering resentment from the financial crisis of a decade ago, where wrongful foreclosures, bank fraud, extortionate mortgage policies and other varieties of bank malfeasance were punished only with greater profits and bigger executive bonuses. Or perhaps it could be related to the long list of similar incidents that have occurred since the crisis. Wells Fargo, for example, was found to have created accounts for over 2 million customers without their knowledge so that marketing personnel could meet what were unreasonably ambitious sales goals.1 In addition to these, recent years have seen banks engage in commodity market manipulation (Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase),2 misuse customer cash (BankAmerica/Merrill Lynch),3 illegally inflate credit card fees (Citibank),4 rig electricity markets (JP Morgan Chase),5 rig foreign exchange markets (Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, RBS),6 rig money markets (Goldman Sachs),7 and even engage in wage theft (SunTrust Bank, JP Morgan Chase).8 , 9 Sadly, this is not nearly a complete list of actual malfeasance,10 and does not even begin to touch on the destructive ways in which the big banks do not support a sustainable economy, failing to support local lending11 making big bets on destruction of the earth’s climate,12 , 13 and plundering public budgets.14

As a result of this behavior, city councils and county boards of supervisors across the country have found themselves under pressure when activists have discovered that the bulk of their government’s money is kept in one of the very banks that appears so often in these headlines. Our cities, counties, and states are among the largest customers of the very banks that fail to serve our communities in so many ways. At the same time, the structure of the market for banking services appropriate for large customers is such that municipal customers find it very challenging to find other banks willing to take their business. Small banks may not have the geographic reach necessary, the range of services, or the staff to handle a government’s business.

They may not actually want the money, either, or not much of it. Because municipal deposits typically exceed the FDIC insurance limits by orders of magnitude, standard practice requires banks servicing government deposits to put up collateral against them. The big money-center banks generally have a great deal of collateral-grade securities on their books, so this can be little more than a bookkeeping transaction for them. Smaller banks, however, have to find collateral somewhere, and this increases the cost of the deposits for them. A bank with only $1 billion of assets in long-term loans (which is a fairly small bank these days) will have a difficult time doing anything constructive with a $100 million account that ebbs and flows with the seasons. Most managers of small banks thus conclude that these deposits are simply not worth the trouble.

This is a problem because as a result there is a lot of money that could be constructively invested in our communities that is instead going to construction projects in Dubai where it is not building pipelines in the Dakotas.15 As of 2012, the Census Bureau counted 89,004 governments, including 35,886 cities and towns, and 3,031 counties, along with 12,884 independent school districts, and another 37,203 special districts of one kind or another.16 Even a small town of 10,000 may have transaction accounts in the millions of dollars, so this is a lot of money. Not counting pension and other trust funds, this is over $1 trillion for county and municipal governments alone, and more than double that to include states. The inclusion of pension funds brings the total to over $5 trillion as of 2012.17 By way of comparison, this is approximately twice the size of the Social Security Trust Fund.

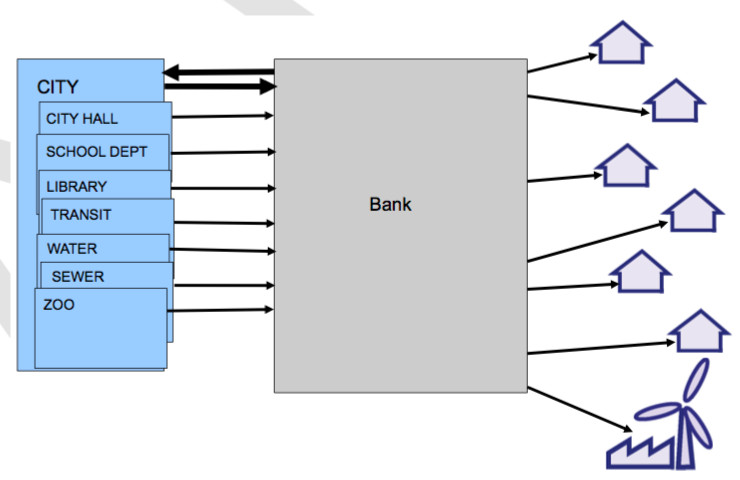

Without an MFA. A bank takes deposits in from one side and makes loans out the other side. A government typically has many different bank accounts with its primary bank, making moving money to another bank a challenging proposition

With a stock of funds so large, one does not need to redirect the whole thing to have a tremendous impact. The ability to move public funds toward productive public investments or even toward economically productive local investments would make a tremendous difference in the state of local economies across the country. Both activists and politicians know this, and yet the market is structured in a way that makes it quite challenging for many governments to find appropriate and willing sellers of banking services.

Compounding the dearth of sellers in the market, there are the difficulties of the buyers, as well. There is a great deal of friction involved in moving transaction accounts from one bank to another. Typically, a government creates new transaction accounts for whatever departments and agencies have discretion over their purchases. This might mean separate bank accounts for payroll and general expenses, but it also might mean more accounts for the water authority, the sewer fund, the parks department, the housing agency, the redevelopment authority, and so on. The accounting requirements for many grants are generally easier to comply with if money is segregated into a separate account. Trust funds will also often have an account, and then there are the odd ones, where the police department has a small discretionary account, or a bequest to the town library was sequestered in another bank account to keep it safe from the town council. In other words, even a small town can have dozens of bank accounts, making it quite onerous to choose a different bank.

Indeed, for many municipalities and counties, shopping for a bank usually involves issuing a request for proposals and several months of vetting because the cost of changing banks is so high. And after a new bank is chosen, there will be several more months of supplying all the different departments and agencies with checkbooks, passwords, account numbers, and night depository keys. One of the keys to a functioning marketplace is that buyers can choose the goods they want to purchase. When a buyer cannot choose among the options, it is hardly a fluid market. With this kind of friction on the buyers’ side of banking transactions, it is little surprise that the market for banking services heavily favors the sellers.

It is often suggested that the solution is for a government that does not like the banking options on the table to create its own by forming a public-owned bank to provide banking services to itself. There is a great deal to be said in favor of such a proposal. The state of North Dakota has happily operated such a bank for a century now, to its great advantage. The territory of American Samoa recently formed a small bank to fill holes in the banking market on the archipelago. Unfortunately, creating a bank requires a great deal of effort, and the US blueprints for a public bank are 100 years old and in need of updating. At least as importantly, a bank is about managing risk, while most governments are quite risk-averse. For many of these, creating a new bank from scratch is a bite they are not willing—or equipped—to take.

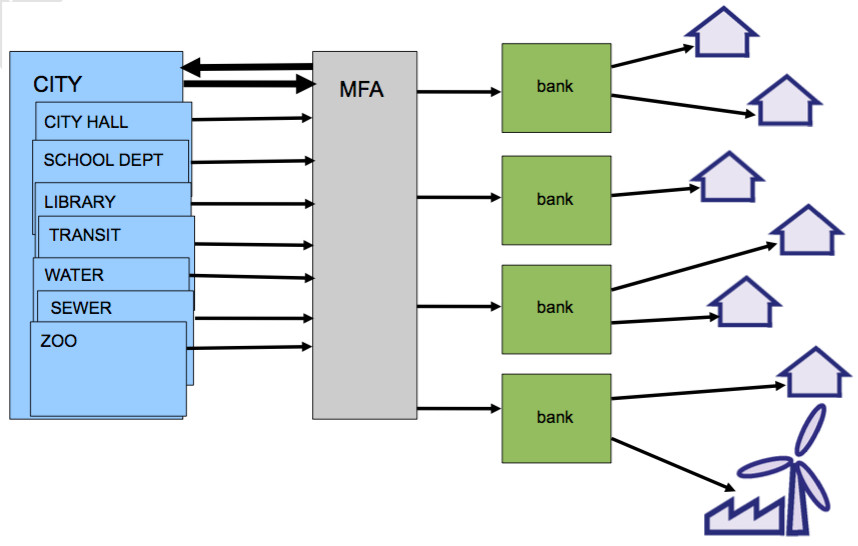

There is, however, a way forward that can restore some competition to the local banking services market, and offer governments a greater degree of control over where their money is invested. A special-purpose, non-profit middleman to broker deposits to small banks could assert control over deposits and move them around quite easily, without the sponsor government being aware that movement was happening. Such a Municipal Finance Agency (MFA) would act just like a bank as far as the government was concerned, accepting deposits and managing separate accounts in exactly the way a bank does.

With an MFA. To the government’s many agencies and departments, the MFA appears to be a bank. But it is actually just a broker, splitting up deposits among several partner banks who are responsible for investing it. The relationship with each partner is much simpler than before

The MFA would use the same account management procedures as any bank. In fact, because most banks outsource software development and maintenance to third party vendors, the MFA could use the same account management software as most banks, since those vendors are happy to sell to anyone.18 As a result, the MFA would slip seamlessly into the same role as the bank that came before it. The relationship between the MFA and the various agencies and departments of the government would be no less complicated than it was before. But since it would manage the accounts, instead of accepting deposits to make loans, the MFA would simply take the funds it has been given and deposit them in one of a collection of partner banks it has recruited to help provide services.

From the government’s perspective, there is hardly any change at all in the relationship, except for two important points. Firstly, the MFA is to be designed to make doing business easy for its government. Because it was designed with the government in mind, it can provide exactly the services needed to streamline business. The second point is more important: unlike any bank in the United States, the MFA will have a fiduciary duty to the government. The government need not wonder if the MFA has its best interests at heart since it was designed to serve the government.

From the MFA’s perspective, its relationship with each partner bank is much simpler than the earlier relationship the government had with its one big bank. It is far easier to contemplate recruiting a new partner—or jettisoning an existing one—than it was for the parent government to do so. This will make the market much more fluid, with the government able to see banks compete for its funds. This will make the banking services market much more responsive to the needs of the ultimate customer in terms of where the money is deployed.

Obviously, an MFA cannot, and should not, be in the business of directing individual loans, but it would be reasonable to expect it to encourage categories of lending among its partner banks with commitments of funds. A bank willing to make loans in a poor community might get a longer-term commitment of funds than one unwilling to do so. A bank that relies on predatory lending could be denied a seat at the table, and so on.

Strictly speaking, the accounting function of the MFA would offer few advantages over what is already available to any government with a robust fund accounting system. Sophisticated governments already can move money from one bank to another with relative ease.

However, one may make two observations. Firstly, though it may come as a surprise to some, not all governments are sophisticated. Secondly, an MFA can be designed to serve multiple governments, which may be a significant advantage to governments without the resources to invest in more sophisticated accounting systems.

A third consideration is political. Most readers of this document will be familiar with the blue ribbon commission of business leaders meeting to develop solutions to one or another important public policy issue. Such commissions are often temporary, but even when they are designed to be permanent, they seldom last longer than the tenure of the mayor or governor who established them. In general, without a business reason to persist, such arrangements do not.

The MFA, by contrast, is by definition a group of banks convened to do a government’s business. It offers a ready-made “round table” of local bankers interested in the fate of the local government, and would make a natural forum for developing credit programs, or making public investments that require credit. It could become a forum in which to market municipal bonds, to create loan insurance funds, or for lenders to seek syndication partners among themselves for large loans.

How would this actually work? At a high level, there are essentially three important components of the MFA. The array of banking services used by most governments is large, so there are potentially many other components, but these three are the basics.

- The software to run the accounting and cash management, to track the deposits and withdrawals, and issue statements that can be reconciled. This software will also accommodate the investment side, though most of that will simply be accounts at the partner banks

- A bank to be the payment processor, to accept checks and cash, and turn them into bank deposits. This bank may or may not be involved in the physical collection of cash and checks. Like the other partner banks, this bank would accept the onus of compliance with banking regulations

- A strategy for dealing with the funds that the local banks cannot absorb. Many states run a cash investment pool, essentially a large money-market fund, for their counties and municipalities. In those states, such a pool would be a solution. Governments in other states can find such services in the private sector

Obviously most governments will also require other services, such as a system of cash collection and night deposits, a lockbox service (to receive bill payments), credit card merchant accounts, credit cards for purchases, and much more. But the basic plan provides a skeletal framework onto which additional services may be hung. Most importantly, the MFA itself can absorb some of the logistical complications of these services, for example contracting with different banks to cover night deposits in different geographic regions and so on.

Depending on the size of the deposits and the fee structure adopted, the MFA could support a director and a small staff of tellers. These staff members would be able to support cash deposits and longer-term deposits, such as bond funds for construction projects and the like.

The exact mix of deposit maturities would vary widely according to the municipality’s circumstances. An MFA might choose to offer such services below the cost of service available from the large commercial banks in the area. Alternatively, an MFA might set its fee levels high enough to accumulate a small store of capital, perhaps to use as a loan guarantee fund, or to create a small revolving fund, or to buy down interest rates for certain borrowers. The possibilities are limited only by the policy priorities of the government, and the board of directors.

The MFA board of directors, presumably a different group of people than the partner banks, would also be an asset to an MFA. These people would, over time, become familiar with the details of the local capital markets. Successful organizations will always seek to expand and forge paths for new opportunities. The tools exist within the MFA concept to grow in directions not anticipated, if the board and sponsoring government are willing. It could become a platform for experiments in payment innovation or risk sharing or a wide range of other possible ways to benefit the local economy.

The governance structure can vary, too. A large enough municipality might choose to go it alone, but a smaller city or county might choose to create a structure other governments might join, such as a “joint power authority” in some states, or just as a non-profit or mutually-owned entity. As we have seen, a larger cash pool is not an unalloyed good, but a larger pool has certain advantages in the interest rates it can attract, so it makes sense to establish an MFA in which other municipalities can participate. A multi-government MFA might become a vehicle through which members can seek to consolidate other financial services, such as financial advising, legal costs, or even bond issuance.

An MFA might be created with one or another of a variety of different policy goals in mind, but the original idea at its core is to harness our communities’ collective assets on behalf of those communities. There is ample data to show that small local banks are far more likely to put their funds into locally productive investments than the big money-center banks. In 2016, banks with assets greater than $10 billion represented 81.9 percent of all bank lending,19 but only 51.1 percent of all small business lending.20

Banks under $1 billion in assets represented 7.6 percent of assets, but 27.8 percent of small business lending. In other words, a dollar on deposit at a small bank is far more likely to be loaned to a small business than a dollar at a big bank. Obviously there is no certainty that a small local bank will be managed by angels,21 but the odds are better that a dollar put on deposit at a small bank will be used for economically productive investments close to home. The structure of the MFA encourages closer oversight of the partner banks and a more responsive marketplace, allowing a government to move its funds with relative ease to the banks that seem best to support its policy goals.

An MFA also provides an arena in which to investigate innovations in finance for governments.22 The MFA will have a board, a director, some staff, and a collection of partner banks, all in a position to ponder and develop initiatives to improve bank service. The modern style is to deprive government of any assets beyond the bare minimum required to run it and then to complain when systems are outdated and clunky. As a result, the deployment of the newest payment innovations is slow in government. Engineering continuous improvement into its workings is itself an important goal.

Finally, one might look to the overall financial picture for motivation to consider an MFA. Faced with a landscape of financial institutions that appear not to have the greater social good at their heart, one possible response is to attempt to regulate them better. There is a small army of people working on that problem, lobbying Congress (and states) for better financial regulation. And, of course, there is a larger army of corporate lobbyists working against them as well. But another possible way forward is to work toward the creation of new financial institutions that have a fiduciary duty not only to their customers, but to the community at large.

Public banks continue to appear in the news as a promising way forward. The Bank of Samoa was already mentioned as an example of a way a government chose not to wait for the market to address its needs, as was North Dakota’s bank. There are other possibilities waiting for governments that are able and willing to develop them as well.

A multi-government MFA could be construed as a buyer’s co-op for banking services, making it perfectly comparable to insurance co-ops in many states around the country. IRMA, an Illinois co-op, was founded in the 1970s, and the Interlocal Trust, a similar arrangement in Rhode Island, in the 1980s. These have operated quietly—and successfully—for decades. Interestingly, some of these have moved beyond group purchases of insurance to actual underwriting. That is, having begun life as a mere purchasing co-op, they have evolved into public-owned insurance companies.

Another useful example is the Build America Mutual bond insurer. This is a mutually-owned insurance company that provides bond insurance for member municipalities, reducing the cost of borrowing for its members. It was an outgrowth of the National League of Cities just a few years ago, but has already reached $52 billion in insured assets for cities and counties in 46 states.23

These are examples of governments not waiting for the market to provide for them, but taking matters into their own hands to design services they need. In other words, institutions like the MFA may represent not only a better deal for this or that government, but the leading edge of a lasting wave of financial reform more fundamental than anything that might come from a better-regulated private market. Let’s see what our governments can do with actual strength in the financial marketplace. We have the financial power to do this. If we will.

- 1Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), "Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Fines Wells Fargo $100 Million for Widespread Illegal Practice of Secretly Opening Unauthorized Accounts," Press release, September 8, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-fines-wells-fargo-100-million-widespread-illegal-practice-secretly-opening-unauthorized-accounts

- 2Joseph A. Palermo, "Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase: Pulling an Enron With Commodities," Huffington Post, July 21, 2013, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/goldman-sachs-jp-morgan-c_b_3632901

- 3Securities and Exchange Commission, "Merrill Lynch to Pay $415 Million for Misusing Customer Cash and Putting Customer Securities at Risk," Press release, June 23, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.sec.gov/news/pressrelease/2016-128.html

- 4CFPB, "CFPB Orders Citibank to Pay $700 Million in Consumer Relief for Illegal Credit Card Practices," Press release, July 21, 2015, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-orders-citibank-to-pay-700-million-in-consumer-relief-for-illegal-credit-card-practices/

- 5Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), "FERC, JP Morgan Unit Agree to $410 Million in Penalties, Disgorgement to Ratepayers," Press release, July 30, 2013, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2013/07/30/jpmorgan-power-manipulation-ferc/2598861/

- 6US Department of Justice, "Five Major Banks Agree to Parent-Level Guilty Pleas," Press release, May 20, 2015, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/five-major-banks-agree-parent-level-guilty-pleas

- 7Commodity Futures Trading Commission, "CFTC Orders Goldman Sachs to Pay $120 Million Penalty for Attempted Manipulation of and False Reporting of U.S. Dollar ISDAFIX Benchmark Swap Rates," Press release, December 21, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/PressReleases/pr7505-16

- 8Patrick Thibodeau, "In turnabout, SunTrust removes contentious severance clause," Computerworld, October 23, 2015, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.computerworld.com/article/2996527/in-turnabout-suntrust-removes-contentious-severance-clause.html

- 9San Jose Spotlight, "Should San Jose waive wage theft policy for Chase bank?" March 17, 2019, accessed May 10, 2019. https://sanjosespotlight.com/should-san-jose-waive-wage-theft-policy-for-chase-bank/

- 10See, for a non-exhaustive list: Ryan Cooper, "A brief history of crime, corruption, and malfeasance at American banks," The Week, October 9, 2017, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.theweek.com/articles/729052/brief-history-crime-corruption-malfeasance-american-banks

- 11Cathy Burke, "Local Banks, Local Lending, Drying Up in Rural America", NewsMax.com, December 25, 2017 accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.newsmax.com/US/rural-banks-local-lending-small-business-war-on-business/2017/12/25/id/833647/

- 12Jo Miles, "Who's Banking on the Dakota Access Pipeline?", Food & Water Watch, September 6, 2016, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/news/who%27s-banking-dakota-access-pipeline

- 13The Rainforest Action Network also publishes an invaluable report called "Banking on Climate Change" that has a grade for dozens of the largest banks. Find it at https://www.ran.org/bankingonclimatechange2018/ (accessed May 10, 2019).

- 14Tom Sgouros, "Predatory Public Finance", Journal of Law in Society, 17(1), p.91, Fall 2015, accessed May 10, 2019. http://sgouros.com/finance/predatory_public_finance_sgourosfinal_.pdf

- 15Bill Chappell, "2 Cities To Pull More Than $3 Billion From Wells Fargo Over Dakota Access Pipeline", National Public Radio, February 8, 2017, accessed May 10, 2019 https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/02/08/514133514/two-cities-vote-to-pull-more-than-3-billion-from-wells-fargo-over-dakota-pipelin

- 16US Census, Census of Governments, 2012. Accessed May 10, 2019. https://www2.census.gov/govs/cog/2012/formatted_prelim_counts_23jul2012_2.html

- 17Jeffrey L. Barnett, Cindy L. Sheckells, Scott Peterson, and Elizabeth M. Tydings, "2012 Census of Governments: Finance—State and Local Government Summary Report," December 17, 2014, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www2.census.gov/govs/local/summary_report.pdf

- 18These are companies such as FIS Global, FIServ, Harland Clarke, and Jack Henry and Associates.

- 19Data from the FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile. https://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/qbp/

- 20U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, "Small Business Lending in the United States, 2016," September 2018, accessed May 10, 2019. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/Small-Business-Lending-in-US-2016-Report.pdf

- 21Some of the nation's most egregious financial scandals have begun with tiny banks, some getting astonishingly far out over their skis. See, for example, the tale of the Penn Square Bank. Mark Singer, "Funny Money," Dell Publishing Co., Inc. 1985, ISBN 0-440-52576-4

- 22As opposed to the innovations for banks, which are often deployed to the detriment of governments, see Sgouros 2015, op. cit.

- 23Build America Mutual, Quarterly Operating Supplement, December 31, 2018, accessed May 5, 2019. https://buildamerica.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1553629440_bam-operating-supplement-2018-12-31-final.pdf