I. Introduction & Summary

In June of 2022, Los Angeles County launched a land banking pilot program, allocating $50 million to begin implementation. The goal of the land bank pilot is to prevent displacement near new development spurred by the Los Angeles River Master Plan. It is part of a new regional focus on avoiding the unintended consequences of new investments: Metro, the region’s transit agency, has also explored land banking as a strategy to prevent transit-oriented displacement as the region builds out new light rail lines.

Historically, land banks have been most active in areas with low land values, with the primary goal of stabilizing neighborhoods. But land banking has successfully preserved affordability in high-value areas–notably in Denver, Colorado. Los Angeles County could be the next proof of concept for an important tool to prevent displacement in hot markets.

This memo explores how land banking can play a role in anti-displacement strategies. It outlines what land banks do, describes the origins and implementation of the Los Angeles land bank pilot, and lays out questions and considerations for land banks in communities where they haven’t been used before.

II. The Problem

Development and displacement. New infrastructure investments bring benefits to neighborhoods, but there are racial disparities in which residents capture those benefits. New amenities like transit lines and green space attract new development and lead to increased demand in the immediate area, leading to higher costs for existing residents and businesses.

For instance, researchers have found that housing costs tend to increase in neighborhoods with new light rail lines, putting additional cost pressure on area residents and leading to displacement. This displacement is not automatic, but historically disinvested Black and brown neighborhoods with a large number of renters are particularly susceptible.

When capital projects are planned for a neighborhood, private developers have a major advantage: they can act proactively during the planning process and buy up properties at a low cost. Organizations working to prevent displacement often cannot do the same. Nonprofit developers, community land trusts, and local governments often lack the capacity and funding to take property off the market before it becomes too expensive or is purchased by private developers.

Los Angeles context. Los Angeles is planning for two major infrastructure projects that will lead to new development.

- Los Angeles County has adopted a Master Plan for the 51 miles of the LA River, which is anticipated to spur development in the areas around the river.

- Metro, the regional transit agency, is currently planning several major capital projects after the voters passed a transit revenue measure in 2016 (Measure M), including the planned West Santa Ana light rail line.

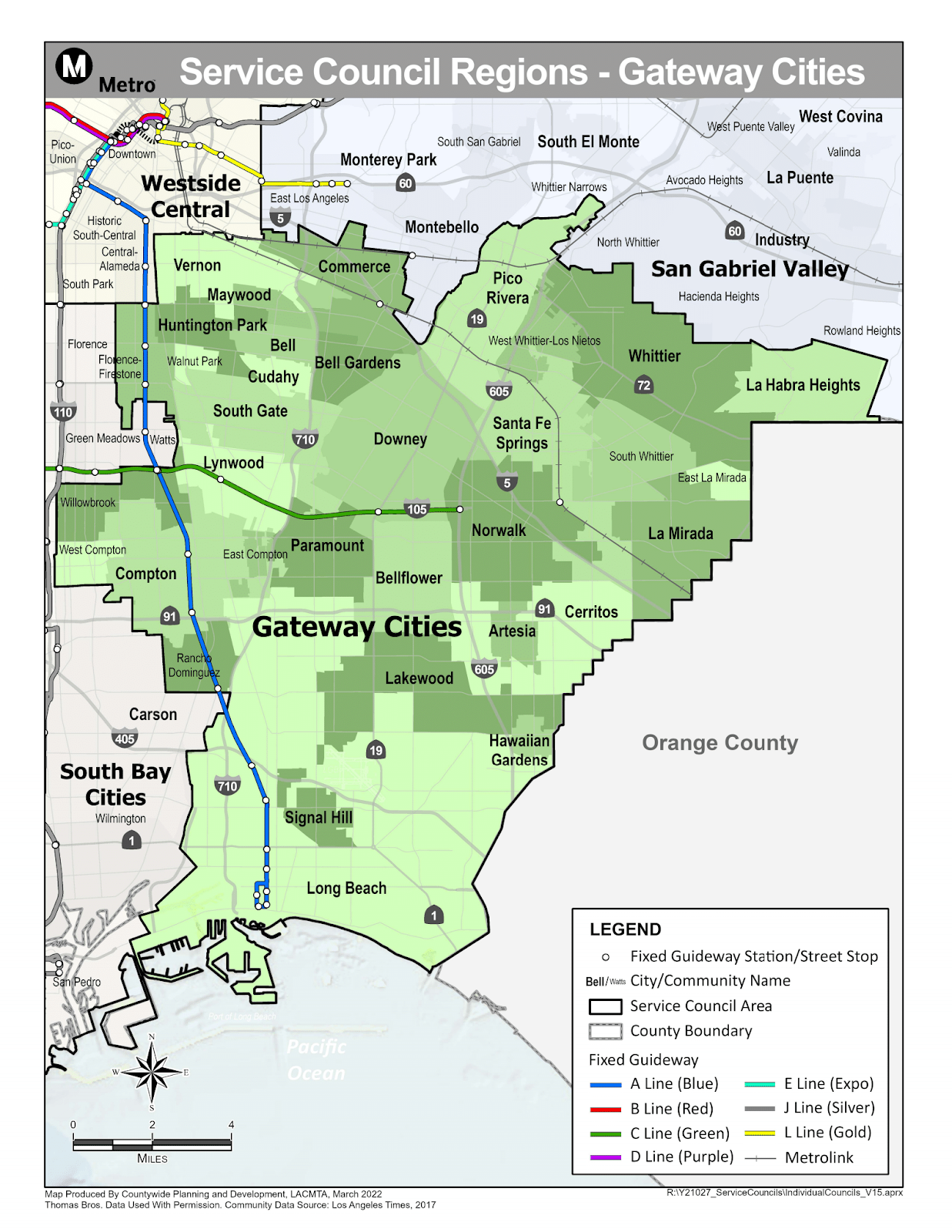

Both the LA River Plan and the West Santa Ana line will have major impacts in the Gateway Cities southeast of downtown, which include communities of immigrants and many low-income renters. Community groups have expressed fears that these projects could lead to displacement and gentrification.

III. Land Bank Basics

Land banks are public or nonprofit organizations that acquire and hold land in order to remove it from the speculative market and reserve it for future uses–often affordable housing.

Land banks have many different uses and objectives. Many communities founded land banks in the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis to acquire foreclosed and tax delinquent properties, with the purpose of preventing blight and stabilizing neighborhoods with low housing demand. The properties are used for a variety of purposes, often for open space or affordable housing.

However, land banks can also operate in “hot” markets. They acquire land early to preserve affordability, especially in areas that will see development and rising prices in the future. They can then hold the land tax-free until nonprofits and other partners have secured funding and are ready to construct or rehabilitate housing on the property.

Examples of this type of land bank include the Urban Land Conservancy in Denver, which has worked with a fund focused on transit-oriented development (see section IV for a case study), as well as Land Bank Twin Cities in Minnesota. Cities like Portland, OR, have also experimented with proactive land-banking while planning for new transit lines.

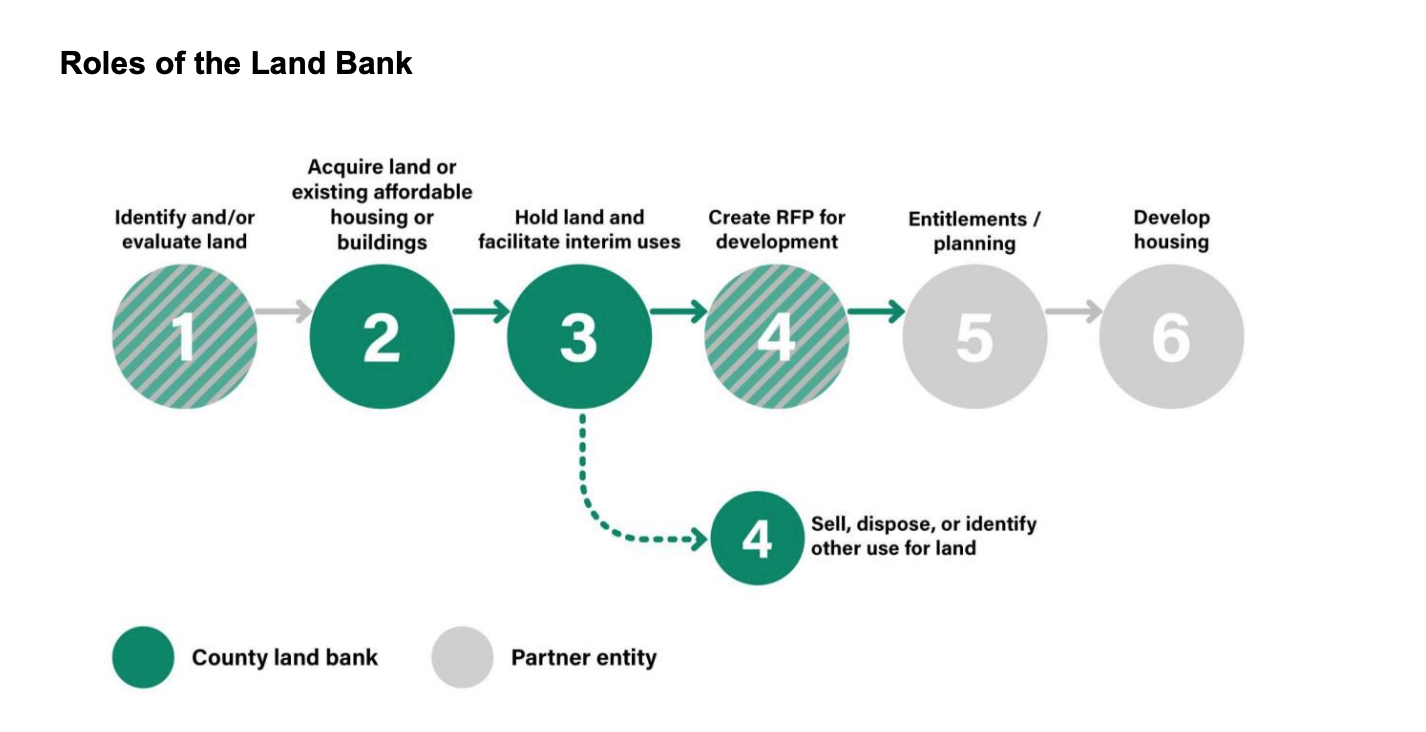

Land banks work closely with other actors in the housing ecosystem. Land banks typically perform a few main tasks:

- Acquiring land, including identifying parcels and performing due diligence

- Holding land tax-free and managing it until it can be used strategically

- Disposing of land, often by selling to community partners

Land banks sometimes take on development roles such as pursuing entitlements, doing land assembly or subdivision, and managing environmental remediation, but they generally don’t construct housing or manage long-term uses.

All of these functions require significant coordination with public and private partners.

- Public agencies–such as transit agencies, state agencies, or local governments–often transfer surplus land that they own to an area land bank.

- Community partners–such as Community Land Trusts (CLTs) or nonprofit developers–often purchase land from land banks. They can also “deposit” land by identifying it for the land bank to purchase and hold tax-free until the partner is ready to develop it. In particular, experts describe CLTs and land banks as complementary: land banks dispose of land, while CLTs acquire it and protect affordability.

Most land banks are based in a specific municipality or county. However, Alabama has a state-wide land bank, and there are some regional land banks that work across jurisdictions. They can be public entities or nonprofits. In some states, land banks are given special powers by state or local governments, including holding land tax-free, expediting the disposition of tax-delinquent properties, or dedicated funding sources.

A self-financing land bank is “largely a myth.” Land banks have some opportunities to recover their costs through land sales (“inventory cross-subsidies”). However, their ability to do this depends on the types of properties they acquire and their objectives. Most large land banks rely on other types of funding, including direct funding from local governments, foundation/private funding, tax recapture provisions, delinquent property tax assessments, and bond financing.

IV. Case Study: Denver's Transit-Oriented Land Bank

Denver has had a land bank since 2003, the nonprofit Urban Land Conservancy (ULC). ULC was founded to create and preserve affordable real estate in gentrifying areas of Denver at a time when the city was growing rapidly and displacement was a major concern.

Transit-oriented land banking. In the mid-2000s, Denver voters passed a new transit-funding measure that authorized major expansions of the city’s transit system. In response to concerns about transit-oriented displacement near new light rail lines, ULC partnered with Enterprise Community Partners and the City and County of Denver to create the Denver Transit-Oriented Development Fund in 2010.

Using this new funding source, ULC could purchase land near new transit facilities and bank it for up to five years. As one example, they acquired an underutilized industrial property along the planned Southwest light rail corridor and held it for about a year, giving a nonprofit developer partner time to secure financing. They then sold the property to the developer, who built the Evans Station Lofts development, a transit-oriented mixed use affordable housing project.

ULC was originally the sole borrower from the TOD Fund. In 2014, the fund expanded beyond ULC and is now managed by Enterprise. ULC continues to purchase transit-oriented properties, mainly through other funding sources.

ULC’s success is not just about land banking. ULC has a unique structure and is involved in many aspects of the acquisition/development process. Depending on the project, they act as a land bank, a community land trust, a developer, and a property management company (see their list of properties for an idea of the range of work they do). They also leverage several revolving loan funds, such as the Metro Denver Impact Facility (MDIF).

In describing ULC’s success, observers point to two main factors: strong partnerships and access to flexible capital.

- Partnerships: ULC often collaborates with affordable housing developers by purchasing and holding land identified for later development. They also partner with government–for instance, ULC recently worked with Denver Public Schools and the Denver Housing Authority to purchase a former college campus.

- Flexible capital: Through these partnerships, ULC has access to significant sources of private and public funding. ULC was part of a collective of foundations, community nonprofits, and businesses called Mile-High Connects, which advocated for equitable TOD during a time of major transit expansion. Their main sources of capital have been investment from local banks, the Colorado Division of Housing, and private philanthropy.

In addition, the Denver TOD Fund has seen success without working directly with a land bank. The Fund originally lent solely to ULC, but since 2014 it has worked directly with nonprofit developers. As of 2022, the Fund had invested $50 million to create 22 developments with 2,100 homes.

V. Land Banking in Los Angeles

Los Angeles County land banking pilot. For the last decade, Sissy Trinh, Executive Director of the Southeast Asian Community Alliance (SEACA), has fought for land banking in Los Angeles to address community concerns about infrastructure-driven displacement. Throughout 2021 and 2022, SEACA and other research partners worked with the LA County Chief Executive Office to explore a land bank pilot as part of the development of the LA River Master Plan. The River Plan will spur new development in several low-income communities and includes land banking as one strategy to achieve its goal of “address[ing] potential adverse impacts to housing affordability and people experiencing homelessness.” In March of 2022, the County Executive produced a report exploring design features and needs for a land bank. The County has also formed new partnerships with community land trusts, funding a $14 million CLT pilot in 2020 to acquire and rehab ‘naturally occurring’ affordable housing.

In June 2023, the County Board adopted both the LA River Master plan and the land banking pilot. The pilot will target land within two miles of the river, though the land bank could be expanded county-wide in the future.

Metro’s involvement. Metro is not officially part of the pilot, but they collaborated with the County on exploring a land bank.

In addition, Metro has done policy work around preventing displacement near new transit lines, especially as they plan for new investments funded by Measure M. Their Transit-Oriented Communities (TOC) policy guides how Metro plans and partners with local jurisdictions and communities, with the goal of “stabilizing and strengthening communities around transit.”

Metro plays a role as a landowner as well. They purchase land near future transit lines for staging and other uses. Once construction is over, Metro develops it via joint development agreements (JDAs) with nonprofits and other entities. As of 2021, the Joint Development policy specifically prioritizes affordable housing (100% income-restricted) and prioritizes housing in areas with greatest need. The 2021 policy update also made some changes to augment Metro’s ability to make “strategic acquisitions”–prioritizing parcels that can later be used for housing.

While Metro is not formally part of LA County’s land bank pilot, they participated in the County’s land bank report and have discussed coordinating more thoroughly with the County to identify properties near transit projects. In the future, they may be able to use strategic acquisitions to bank land themselves, or partner with the County land bank to assemble parcels close to transit for affordable housing.

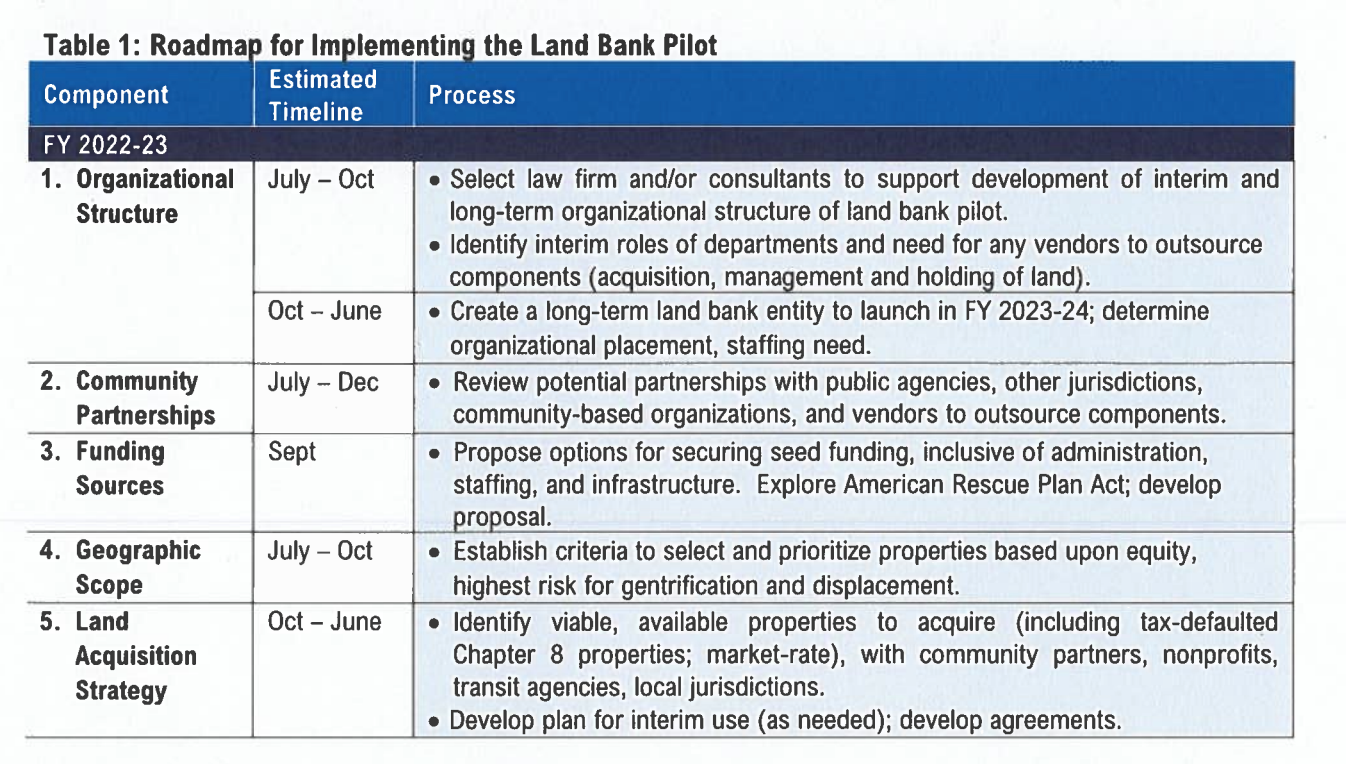

Implementation questions. The land bank pilot is currently in the implementation stage. The County allocated $50 million in federal American Rescue Plan and affordable housing dollars for start-up costs. Initially they planned to identify specific properties and develop purchase agreements by the end of the fiscal year in June 2023.

Since then, competing policy priorities and the threat of an American Rescue Plan clawback resulted in the county cutting into the funding for the land bank pilot. In Fall 2023, the Board of Supervisors approved the transfer of $25,000,000 of Land Bank Pilot program funding to support rent relief programs. The County executive office does not believe this will affect implementation of the land bank pilot, as they consider other funding sources to make the program whole again.

The County executive has not yet met its goal to develop a land acquisition strategy, and is now looking to contract out the effort. As of March 2024, County executive staff are working to execute a contract with a consultant to conduct outreach with affordable housing developers who will identify parcels of interest. The County will then assess these properties and determine if they are feasible options. If one of these parcels is selected, the developer who proposed it will have a first right of refusal to develop it if they can prove their development capacity.

As the County executive considers partnerships, funding options, parcel selection and acquisition strategies, there are a few major questions about what will make the land bank most effective, both in the pilot stage and for the long term.

Who will manage the land bank? What’s the structure and legal authority? Unlike the Urban Land Conservancy in Denver, the LA land bank will be a governmental entity rather than a nonprofit. So far, the County executive office solely implements the land bank pilot. However, alternative structures like a Joint Powers Authority could allow for more coordination with local government partners like Metro.

Who will the land bank partner with? The County’s plan describes community partnerships central to the land bank’s success. Local community-based organizations can “ground truth” potential properties for acquisition and ensure that community needs are represented in the disposition process. In particular, community land trusts will likely play an important role. The LA Community Land Trust Coalition has been working with the County since early in the pandemic, including on the $14 million CLT pilot project.

What is the best land acquisition strategy? The County initially set out to design a set of criteria for selecting which properties to acquire, and the County Executive’s report recommends developing a data-driven strategy for acquiring properties at greatest risk, drawing on vulnerability mapping work already completed by the County. However, now the County will rely on a consultant to conduct outreach with mission-driven developers to identify parcels. This process has been long, and extending timelines might defeat the purpose of employing a land bank in a hot market. Ideally, the pilot land bank would have acquired land as soon after the announcement of the LA River Plan as possible, getting ahead of speculative pressure and climbing land values. Although this approach does have some marginal benefit of ensuring the acquired parcels are actually of interest to community developers. Additionally, while the County has focused on vacant and underutilized properties for new construction, in the future they may expand their scope to include preserving naturally occurring affordable housing like many community land trusts do.

What are the funding sources? What is the level of need? The County estimates that the $50 million they initially allocated to the pilot will be enough to purchase land for 800 units of housing. As of now, that funding has been slashed in half, and it is unclear what source will replenish it. In the long term, the land bank may require some kind of ongoing funding–both to fund operational costs such as due diligence and property management and to fulfill its mission of providing affordable land to CLTs and affordable developers. The land bank will have a limited ability to recoup costs by disposing of land at a markup, since they will need to ensure land is affordable to CLTs and nonprofit developers.

Environmental remediation will be a major issue for the properties the land bank is likely to acquire. There may be tradeoffs between focusing on the highest-value properties and buying cheaper parcels, which often have significant remediation needs. Contaminated land increases the cost of putting the land to use, and raises a risk of exposure to future residents if clean-up is inadequate.

Opposition and critiques. Direct opposition to the land bank pilot has been limited, but the proposal has raised questions and concerns about resources and effectiveness.

Tax revenue and competition. Cities and local governments often count on increased tax revenue from rising property values after an infrastructure investment. In Los Angeles County, several of the Gateway Cities have been vocally opposed to the land banking pilot, arguing that it undermines their planning. The cities have also argued that the land bank will compete with more traditional affordable housing programs.

Will it do enough? Others have raised concerns that the land bank won’t do enough to prevent displacement and gentrification, advocating for additional strategies to support Gateway Cities communities, such as strong tenant protections and homeownership supports. One question about land banks in tight markets is whether they are capable of competing with other market players for desirable properties. Even in low-demand areas, the ability to compete for properties can be a challenge.

VI. Looking Ahead

Land banking as a solution. While implementation of the Los Angeles County land bank is still in its early stages, it could be the proving ground of a new tool to prevent displacement in hot markets. In these environments, land banks offer some major benefits:

- Land banks aid in affordable housing preservation. They can intervene in a hot market earlier than nonprofit developers and CLTs that need time to identify and secure funding sources to acquire land.

- Land banks make developing affordable housing in a hot market possible. They create new breathing room for community and non-profit developers, by holding land tax free until they can move forward with a project.

- Land banks facilitate new partnerships. They create opportunities for collaboration between transit authorities, local governments, and other public entities, and ease the process of utilizing public surplus land.

However, there are also implementation questions about what makes a land bank effective:

- They need sufficient funding and staff to operate while fulfilling their objectives. A flexible and patient capital source can allow a land bank to act quickly and be competitive in the market without having to worry about recouping costs from nonprofit and CLT buyers.

- They need strong partnerships with local governments, nonprofits, CLTs, and developers. These connections are crucial for identifying the most at-risk properties, creating community-relevant affordable housing, and fostering collaboration that maximize public resources.

- They need the capacity and legal authority to operate efficiently and effectively, whether they are a public entity or a nonprofit. They need to be able to conduct due diligence, hold land, and manage properties. Capacity challenges have implications for the land bank’s ability to act quickly, compete for properties and align with planning processes and equity goals.

Is the juice worth the squeeze? Land banks can play an important role in mitigating displacement and preserving affordability. With the right resources and partnerships, they are uniquely positioned to support affordable developers and CLTs that struggle to compete with the market in rapidly changing areas.

That said, land banking is not a simple solution. Its effectiveness depends on availability of resources, staff capacity, and it must fit into a larger strategy in order to truly address displacement. Land banking can take many forms, and the LA land bank pilot is just one. As the pilot takes shape, its successes and challenges will be an important lesson for how this adaptable model can work in new communities.