Paper accepted December 2019

Download a PDF of this paper here.

Southern California is one of the fastest-growing population and economic centers on the planet, where the tech industry’s explosive growth has spun off enormous wealth across the region. But a sharp divide separates the lives of those in upscale coastal areas from the realities of the inland areas where fewer than half of the jobs pay a livable wage. During the last three decades the Inland Empire region of Southern California has been experiencing a period of rapid growth, becoming a center of major racial and economic change. Despite being at the epicenter of the last decade’s housing bubble and economic collapse, the region has been one of the fastest growing in the nation in terms of job growth and population changes.

The combined population of the counties of Riverside and San Bernardino has tripled since 1990, and the area is now home to 4.6 million people. With a population larger than 25 US states, and physical size covering more than one-sixth of California, the region is home to many diverse populations. As growth continues to press eastward, the region continues its long march to recovery from the 2008 housing crisis, which came to be known as a cautionary tale of overdevelopment and lending speculation.

This paper is about a rapidly changing and incredibly diverse region that was uniquely at the heart of a subprime mortgage-induced housing boom. During the boom, borrowers of color were targets for subprime lenders who systematically targeted their neighborhoods with aggressive marketing campaigns to take out loans they could not sustain. With the lure of affordable homes in relative proximity to a major metropolis, the region became one of the nation’s largest migration destinations for Black and Latinx households, further fueling demand for housing. These dynamics culminated in a highly racialized housing and economic disaster marking the onset of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s. While large parts of the country have largely rebounded from the Great Recession, there are many communities in the Inland Empire where the fallout from the financial crisis is still a daily fact of life. As these racial, economic, and social divides have grown more severe in the years since the housing bust and Great Recession,1 the hope is that this paper provides clarity on the intersections of these relationships, and what could be done differently in the event of future downturns.

The Demographic Transformation

Like most other major metropolitan areas, the Inland Empire region rose from humble

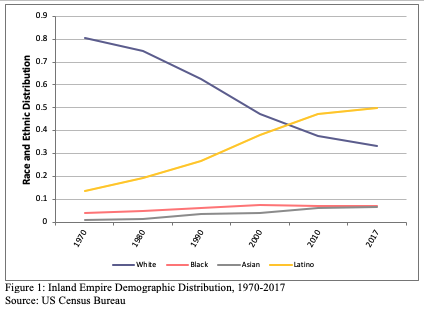

origins to achieve the scale and status of a major center of demographic, racial, and economic change. In 1970, the Inland Empire was 80 percent white (non-Hispanic). But with increasingly dwindling space in the neighboring coastal counties, the region has seen dramatic increases in its Black, Latinx, and Asian populations (Figure 1). The scale of this sweeping transformation has seldom been seen in an American metropolitan landscape. The inland area is now majority Latinx, while whites now comprise less than a third of the region’s population, compared to 62 percent in 1990. Between 1980 and 2010, the region added 250,000 Black residents, many of which were middle class, leaving traditionally Black neighborhoods in central Los Angeles to pursue homeownership in newer outlying suburbs. In fact, between 1970 and 2017, the suburban fringe saw its Black population increase almost seven-fold, from 48,000 to approximately 328,000. In more recent decades, Asians have become the fastest growing racial group in the Inland Empire, more than doubling between 2000 and 2017, from 140,000 to approximately 295,000 (US Census Bureau, 2018).

The desire to own a home in particular was a central factor behind the region’s profound racial transformation (Pfeiffer, 2012). For several decades, the region ranked among the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the country, with many moving there to find more space and housing that was more affordable than in coastal Southern California (Mordechay, 2018). In 1989, for example, the median home price in Los Angeles County was close to $100,000 more than in the Inland Empire. By the mid-2000s, the price differences in average single-family home had jumped by well over $300,000 ($715,000 compared to $387,000). The Inland Empire came to be imagined as a “new frontier” of rapid growth—a place where families could escape from the crime and congestion of the urban core and access a higher quality of life and better schools for their children. The rapid growth fueled a massive construction boom, creating a buoyant labor market for low-skill workers, drawing in many more residents, especially from Mexico and Central America (Mordechay, 2014). On the supply side, new home construction in the Inland Empire took off. On the demand side, income and job growth, as well as financial deregulation, enabled more families to buy homes. During the 1990s, rates of subprime mortgage lending, home equity borrowing, and home ownership increased among households of color, creating the largest housing boom in modern US history. At the peak of the building boom in 2005, an extraordinary 52 percent of all new homes constructed in California were built in the Inland Empire (Husing, 2005).

Subprime Lending

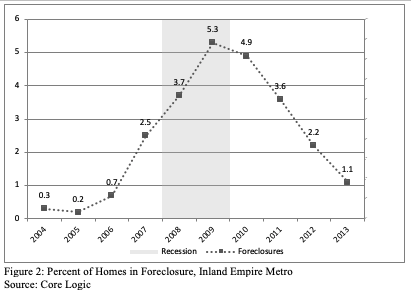

Between 2000 and 2003, subprime loans accounted for 7 percent of all mortgages in the US. By 2006, the peak of the housing market boom, their share jumped to over 20 percent, before collapsing to 1.5 percent in 2008 (Bocian, Smith, Green, & Leonard, 2010). These higher risk mortgage products were segmented geographically, where lenders were incentivized to exploit the interdependent inequalities of race, class, and place (Molina, 2016). Concentrated, segregated populations of under-served households of color with limited financial savvy or access to consumer protections were ideal targets for predatory brokers marketing subprime loans. An Inland Empire region that had experienced two decades of rapid growth of overwhelmingly Black and Latinx households, frequently concentrated in low-income zip codes, became ripe for exploitation. These conditions set the stage for an epic construction boom where housing values in the region increased by over 130 percent between 2000 and 2006 (see figure 2), almost double the rate of US housing price increases.

The enormous growth in the Inland Empire was driven by aggressively pushed subprime loans, by far disproportionately on Black and Latinx households. From the perspective of the borrower, the main feature distinguishing subprime from prime loans is that subprime loans actively price the loan based on the risk associated with the borrower. In theory, the interest rate on the loan depends mostly on the income-to-debt ratio and credit scores. While income was indeed positively associated with receipt of subprime loans for households of color, many studies since have documented that middle- and upper middle-class Black and Latinx families were targeted for subprime loans when they could have qualified for less risky prime loans (Mordechay, 2018; Faber, 2013). One study of the racial disparities in subprime lending throughout the 1990s and early 2000s found that they were largely a result of lending discrimination and that up to half of the subprime borrowers could have qualified for less costly prime mortgages (Barwick, 2010).

This racialized housing boom was followed by the foreclosure crisis whose negative consequences disproportionately affected Black and Latinx borrowers and homeowners (Rugh & Massey, 2013; Darden & Wyly, 2010). During the peak of the housing boom, in no other part of the country did subprime loans account for a bigger proportion of the overall mortgage market than Riverside County (Mayer & Pence, 2008). The Inland Empire had become ground zero.

The social and economic consequences for the families affected by the crisis were vast and long lasting. The collapse of the housing market that hit the Inland Empire region in the summer of 2007 was only the beginning of the devastation experienced by many of these families. The financial crisis that soon became global lead to a massive wave of foreclosures, decimating wealth accumulated by the region’s Black and Latinx families. This was followed by skyrocketing unemployment, rapid increases in poverty, residential displacement and housing instability, and children of displaced families struggling to cope with the economic shock, to name just a few of the consequences. While the rest of the country was going through a recession, the Inland Empire would soon be in the grips of a depression.

The Crisis

The Great Recession caused a dramatic reduction in the wealth of millions of American households, particularly wealth in the form of home equity. The net worth of the typical household plunged by 40 percent as a result of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. Relative to white wealth, Latinx and Black wealth was hit especially hard. Between 2005 and 2009, median household wealth declined by 66 percent among Latinx households and 53 percent for Black households compared to 16 percent among white households (Kochar, Fry, & Taylor, 2011).

These declines were especially acute in the Inland Empire which soon became known as the “foreclosure capital” of the nation (Pfeiffer, 2012). There, at the peak of the crisis, over 5 percent of all homes were in foreclosure (figure 2). In 2008, foreclosure rates in Riverside and San Bernardino counties were nearly 6 and 3.5 times larger than neighboring Los Angeles County, respectively (Hipp & Chamberlain, 2015). The financial losses associated with foreclosure are substantial. For homeowners, credit scores and access to credit are wrecked, which affects their ability to move on to a new home and lessens their ability to get loans for future purchases. Poor credit scores may also impede efforts to get jobs, as some employers access credit ratings for new hires.

While the long-term consequences of the housing crisis have not yet been thoroughly studied—as they are likely still unfolding—communities with high concentrations of foreclosures experience a host of negative consequences. These include increases in crime, declines in property values, and a reduction in tax revenues that fund local schools and basic municipal services (Molina, 2016). Because foreclosures often result in residential moves, children in foreclosed households frequently change schools in the middle the school year. One study of high school youth in San Bernardino found that during the recession, school mobility rates for Black children were especially high, even after controlling for socio-economic status, and that school changes were likely to result from foreclosures and to lead to new schools that were lower performing than their original schools (Mordechay, 2017). In many cases, it was Black children from middle-class households that were particularly vulnerable to school changes due to the group’s precarious position in the housing market leading up to the recession (Mordechay, 2018). School changes are associated with a range of negative outcomes, such as lower test scores in math and reading, grade retention, lower self-confidence, discipline issues in schools, dropping out, and even drug abuse later into adulthood (Gasper et al., 2012; Mordechay, 2018).

Housing instability does not only wreck credit histories and disrupt work and schooling. It can also plunge families into sudden poverty. In California public schools, the number of children qualifying for free and reduced lunches, a common proxy for poverty, increased from 50 percent before the recession to 59 percent by 2013. However, the rate more than doubled in one of the Inland Empire’s largest school districts in San Bernardino—increasing from 25 percent to 56 percent during the same time period (Mordechay, 2016). Across the Inland Empire, those increases have continued beyond what for many parts of the country was the recovery period, with the rate in San Bernardino Country hitting 70 percent by 2017 (California Department of Education, 2018). In neighboring Riverside County, the share of students on free or reduced-price lunch increased from 53 percent to 64 percent during the 2007-2017 period. Decades of research has shown that after controlling for a host of variables, the effects of poverty on academic achievement are significant and long lasting (Duncan et al. 2000, 2010). These effects at the school level mirrored local communities across a region that saw the largest increases in poverty rates during the Great Recession (Kneebone & Garr, 2010).

Aftershocks

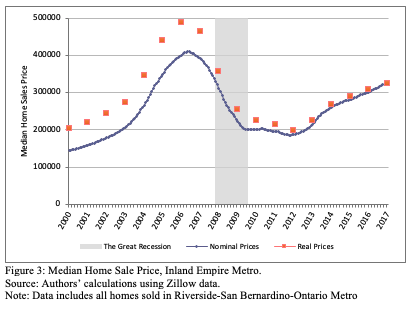

It has been over ten years since the deepest economic contraction of the post-World War II era. The country has rebounded in many ways, but many communities are still suffering from its legacy. In many parts of the southern California coast, housing prices have long surpassed the pre-recession peaks of 2006. In the Inland Empire, which saw over a 50 percent decline in home values by the bottom in 2012, housing has not recovered. While nominal housing prices are indeed approaching pre-recession levels, real prices (adjusted for inflation) are well below pre-recession peaks (see figure 3). As a result, many families that saw their largest asset of wealth collapse over a decade ago are still far from recovering the losses.

Many of the homes that families lost through foreclosure were purchased by a flood of investors, and then rented out to the same families that once owned them. In early to mid-2010, close to a third of homes sold in the Inland Empire were bought by investors, largely an outcome of their ability to purchase foreclosed properties with cash (Pfieffer & Molina, 2013). Because investors purchased much of the inventory, many of the families that saw their wealth wiped out during the financial crisis have not benefited from the housing boom of the past eight years, which is the third largest in the modern era (Shiller, 2019). They have not been able to benefit from perhaps the only upside to the real estate crash—historically low prices and interest rates.

Families of color tend to hold more of their wealth in their homes, which rendered the crisis's effects particularly devastating for households that foreclosed or experienced dramatic property value declines. While it has been well over a decade since the crash, one recent analysis by the Economic Policy Institute found that across the US, the long-standing racial disparities in homeownership have worsened in the post-recession recovery. Perhaps most surprising, the analysis found that the homeownership gap between whites and Blacks with a college degree widened even more than the overall average difference between the groups (Bivens, 2019). This finding challenges the conventional wisdom that a bachelor’s degree is a reliable stepping stone on the path to upward mobility. Indeed, one recent study finds that Black households in the US headed by a college graduate have less wealth than white households headed by someone without a high school degree (Hamilton et al., 2015).

Wealth of course provides families with capital to purchase or invest in potentially appreciating assets, which in turn, iteratively generates more wealth. Deep losses to a family’s wealth, especially losses to home-equity wealth, can drastically diminish the ability to assist children in many ways, including help pay for college or a down payment on a home, which would beget yet more wealth and opportunity across generations. The intergenerational impact of the Great Recession is not going to be fully understood for some time, but the racial effects are sure to be profound.

Implications for the future

Despite the official end of the recession in late 2009, many distressed communities and individuals continue to suffer from the plummeting wealth and home values, long-term unemployment, poverty, and stagnant incomes it induced. Not surprisingly, this is particularly true where the housing crisis hit hardest. One recent report analyzing communities that have missed the benefits of the most recent economic boom found that over 20 percent of the city of San Bernardino’s population was living in distressed zip codes. Such communities have high concentrations of poverty and housing vacancies, high shares of adults without a high-school diploma, high unemployment and underemployment, and are racially segregated. Indeed, the consequences of distressed communities extend far beyond the individual neighborhoods being left behind.

The Inland Empire enjoyed a massive demographic and economic boom for the better part of the prior two decades, until the housing market bust. The recession that followed erased more than a decade’s worth of the region’s job growth, and billions of dollars of wealth. In the lead-up to the financial crisis, economic opportunity remained deeply unequal across racial groups, but economic trends pointed to an America that was on a path toward narrowing the stubborn wealth gap. However, the deeply rooted inequalities of race, class, and geography fueled a credit boom predicated on financial institutions engaging in discriminatory and predatory lending that accelerated the housing market collapse.

Although the Inland Empire is no longer in economic peril after years of growth, many families remain worse off than before the Great Recession. The challenges revealed throughout this paper can only be addressed by first understanding how inequalities of race, class, and place set the stage for a subprime-induced real estate bubble that lives with us still today, exacerbating those very same inequalities. The racialization of the foreclosure crisis occurred because of a systematic failure to enforce basic civil rights laws, with discriminatory subprime lending becoming the latest in a long line of illegal practices by the real estate and lending industries that have targeted people of color in the United States. Large scale economic shocks will continue to be a feature of the global economic landscape. Without a strong infrastructure for advocacy and coalition-building, legal enforcement, consumer protections, and fair housing policies that can work to help stabilize the most at-risk families, these shocks will continue to bring ever-widening inequality, impacting not only current but future generations.

Kfir Mordechay is an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education and Psychology at Pepperdine University

- 1In the United States the Business Cycle Dating Committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is responsible for the dating of the US business cycle.