November 13, 2014

Nov. 13, New York, NY: A new report released today addresses the great American racial conundrum: the vast majority of Americans believe racism is wrong, yet evidence showing that race often determines how people are treated is overwhelming.

In “The Science of Equality Volume 1: Addressing Implicit Bias, Racial Anxiety, and Stereotype Threat in Education and Health Care,” the Perception Institute, a national consortium of social scientists and legal scholars, begins a series of landmark reports to understand this challenge and to provide empirically tested solutions to address it.

FROM THE AUTHORS

In the late summer of 2014, an unarmed young black man, Michael Brown, was approached by police officers as he walked in the street in Ferguson, Missouri. Five minutes later, he was dead with six gunshots in his body – two to his head. Grief turned to rage in his neighborhood when the mainly white police department responded using military force, and the rage grew more volatile. The Department of Justice is now investigating.

This was not an isolated event this summer. Eric Garner in Staten Island and John Crawford in Ohio were both killed by police. Marlene Pinnock was repeatedly punched in the head by a police officer in Los Angeles. Neither these deaths and assault, nor the impassioned responses, occurred in a vacuum.

This report, released in the fall of 2014, details the social science that can help us understand the day-to-day dynamics of race and how to alter the circumstances that too often culminate in tragedy.

FOREWORD

Last year, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, honoring the historic struggles for racial equity and justice waged during the Civil Rights Movement. And yet in the last few years, we have seen far too many killings of unarmed black young people rise to the level of national public consciousness, some within the span of just a few months. With each death, we’ve committed a new name to memory: Jonathan Crawford III in Ohio; Eric Garner in New York; Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Renisha McBride in Michigan; Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis in Florida; and Jonathan Ferrell in North Carolina. And the list is growing. With each new name, we’ve learned their unique personal histories and debated different accounts of what might have happened in each instance. Mostly, we have mourned the eerily familiar similarity in each of their tragic deaths: how black people, particularly men and boys, are perceived is inherently linked to their survival. Perception can mean the difference between life and death.

Even more familiar is the polarized, defensive, and entrenched way in which our racial discourse responds to these losses. Families, friends, and advocates are outrageously put in the position of defending the basic humanity of the victims just to secure the most minimal inquiry into justice that would be so easily afforded to most other Americans. Many others legitimately struggle with racial ambivalence as they reconcile their own experience around race with the alarming patterns of systemic injustice being revealed with such frequency. And predictably, a small but vocal minority will leap to justify the killings and excuse a world in which black men and boys should be feared and assumed criminal until proven otherwise. Our challenge is to find inroads to a meaningful, productive conversation addressing the perceptual challenges black men and boys face – which now often ends before it really gets going.

As tragic as the last few years have been, we have also seen glimmers of hope in the way new thinking and new research, particularly in the mind sciences, have emerged to push our conversations, and indeed our imaginations, beyond the historical frameworks and rigid binaries that limit our understanding of race. The public adoption of seemingly academic ideas like implicit bias, embedded stereotypes that heavily influence our decision-making without our conscious knowledge, signifies a willingness to delve deeply into that which makes solving our race challenges seem so intractable. The Perception Institute, a consortium of leading social scientists engaged in the mind sciences, is proud to be a part of a wide community of scholars, advocates, and funders, bringing implicit bias and other ideas into the mainstream. Last year, we released a landmark report, Transforming Perception, in which we detailed how subconscious processes work to reinforce and undergird structural barriers to equality in the criminal justice, education, and health care sectors. Transforming Perception was an effort on our part to increase awareness and understanding of how the mind and race interact.

As important as implicit bias is to understanding race and our daily lives, however, at its best, it is a diagnosis of perception. What we desperately need to move forward is a prescription grounded as much in the complexity of the mind as in our historical analysis of structural barriers. Implicit bias and perception are often seen as individual problems when, in fact, they are structural barriers to equality

The harrowing concentration of lost lives of young black men and boys in the summer of 2014 illustrates the urgency of understanding that the recognition of the pervasiveness of implicit bias is not itself a silver bullet. The Research Advisors to the Perception Institute have been engaged in empirical work identifying effective interventions to reduce bias and as important, identifying related phenomena, racial anxiety and stereotype threat, that must also be addressed to create the equal society we all want to see.

Our response is a new report series: The Science of Equality. This series is designed to examine and explain the perceptual distortions that underpin implicit bias and the anxiety that ensues when race is expressly discussed. As we demonstrate in this report, stereotype threat, which causes our cognitive capacities to diminish when we worry that we might confirm a negative stereotype about our identity group, and racial anxiety, where our discomfort around inter-racial interaction causes the very negative experiences we’re worried about, are key to addressing a host of racialized harms. Future volumes will address their role in the contexts of the media, politics and policy, employment, and criminal justice.

This first volume of The Science of Equality, Addressing the Impact of Implicit Bias, Racial Anxiety, and Stereotype Threat in Education and Health Care, draws on over two hundred studies to describe the operation of implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat; to document how students of color are both over disciplined and given too little feedback on their work in the classroom; to examine how standardized tests lowball the aptitudes and abilities of black and Latino students; and to show how the fact that doctors are far from immune from the kinds of biases and anxieties that affect all of us leads to worse outcomes for African Americans and increased distrust between black patients and white doctors.

We live in a time when discrimination looks less like a segregated lunch counter and more like a teacher never calling on your son or a doctor failing to inspire trust in your daughter and improperly diagnosing her illness as a result. The Science of Equality, Volume 1 shows the role perception plays in our daily lives from the mundane to the tragic. It’s our sincere hope that translating these insights can make the complex science around race and the mind accessible and show how these scientifi c phenomena affect every sphere of our lives.

TWO STORIES

A sixth-grade boy, not too tall with short hair and brown skin, climbs onto the city bus on his way to middle school. He would like to get some reading done before school and sees an open seat near the front of the bus. It would be quieter here than the back where other kids from his neighborhood are talking and joking, but the white lady in the next seat over looks nervous when he moves toward the seat. Never mind. When the bus drops the kids off at school, the security guard makes him empty his pockets and looks in his backpack. Again? He keeps his eyes on the ground, ignoring the other kids streaming past. He is kind of looking forward to Humanities; they are getting back essays on Ancient Egypt, and he worked hard on his. The teacher hands back the essays. An A! But the teacher didn’t give any comments or suggestions. He looks at the kid next to him. He got an A, too. Did everyone? Did his work even matter? Science is next. The worst. The teacher never calls on him or any of the other black kids. Today is the end-of-semester test. He studied most of the weekend, but the test is really hard. Finally school is done. His mom is picking him up for his doctor appointment – his asthma has been getting worse. The doctor doesn’t ask too many questions, and the appointment is over quickly. No new medicine or anything. The nurse smiles at him and his mom. She looks a little like his aunt. He smiles back.

The doctor welcomes the boy and his mother into her office. This is a first visit, but she sees from the chart that the boy has been getting medication for asthma for several years. She is careful to first talk to the mother. In her recent “cultural competencies” seminar they were taught that with black families it is important to show respect to the parents by mainly addressing them. The visit is fairly short; it doesn’t seem like much has changed for the boy. As they leave, the doctor sees the boy smile at the nurse. She is a little surprised. He seemed distant, or at least shy, with her. As the boy and his mother leave the office, the nurse gives her a “look.” What did she do this time? The doctor moved to this practice and to the city from the suburbs fairly recently. She feels like she has tried to get along with this nurse. She compliments the nurse on her work, but it seems like she is always saying the wrong thing. Last week she accidently mixed this nurse up with another nurse who is also black. She felt so stupid, they don’t really look alike, but all of the other nurses are either white or Latina, and she was moving quickly. Lately, when she goes into the staff room and she sees the two black nurses sitting together, she goes and eats in her office. It is so awkward. And who can she talk to? She could call her friend from medical school who is black, but ....

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Most Americans agree that people of all races and ethnicities should be treated respectfully and fairly. Yet we are beset by news reports and personal experiences (like those illustrated above) that tell us that race and ethnicity continue to matter and affect how people are treated and how they interact with each other. The science of “implicit bias” – automatic associations of stereotypes or attitudes about particular groups – has emerged in the public discourse about race and ethnicity and provided a much needed explanation. People can have conscious values that are betrayed by their implicit biases, and implicit biases are often better at predicting discriminatory behavior than people’s conscious values and intentions.

But implicit bias alone doesn’t explain all of the ways in which racial and ethnic dynamics affect day-to-day life and perpetuate disparities. Racial anxiety and stereotype threat are also critical barriers to fair treatment. They help explain why white doctors may have shorter visits and less eye contact with black or Latino patients, why white teachers may give less critical feedback to black students, and why people of different races and ethnicities sometimes find dealing with each other so challenging that they avoid doing so when they can.

Interventions to deal with implicit bias – which often involve enhancing awareness of racial bias – must also address people’s concerns about navigating discussions about race and their anxieties about appearing racist. Otherwise, one racial dynamic may be lessened but another triggered.

This report describes cutting-edge research on implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat – and the interventions that help to reduce them and their effects. The reality of implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat confirm that race still “matters” – both among people of color whose experiences verify their presence and among many whites who genuinely consider themselves non-racist even if their behavior may sometimes suggest otherwise.

We also recognize that addressing the problem of race at the individual level is not sufficient. But it is necessary. Structural and institutional arrangements are critical, but individuals’ behaviors within institutions are also important. In order to challenge structural racialization and inequality in society’s institutions and culture, individuals must be equipped to modify patterns of behavior and persuaded to support policies that will do this work.

Below we describe the content of the report and briefly note the key concepts. The body of the report includes detailed discussions of the concepts and the studies that support them. We also include an extensive bibliography at the end of the report for those who are interested in further study

PART I

Part I describes of the science of implicit bias, how it is measured, and its behavioral consequences. Implicit bias refers to the process of associating stereotypes or attitudes toward categories of people without conscious awareness.

- Implicit: A thought or feeling about which we are unaware or mistaken.

- Bias: When we have a preference or an aversion toward a person or a category of person as opposed to being neutral, we have a bias.

- Stereotype: A specific trait or attribute that is associated with a category of person.

- Attitude: An evaluative feeling toward a category of people or objects – either positive or negative – indicating what we like or dislike.

Implicit Bias Affects Behavior

Implicit biases affect behavior and are far more predictive than self-reported racial attitudes. In this part we describe the studies that have demonstrated links between implicit bias against blacks and a number of critical real-life scenarios, including:

- The speed and likelihood of shooting an unarmed person based on race

- Employment callbacks relative to equally qualified white applicants

- The rate of referring otherwise similar black and white patients with acute coronary symptoms for thrombolysis

- Why black defendants with stereotypically black features receive longer sentences, and why stereotypically black defendants are more likely to be sentenced to death in cases involving white victims

PART II

Part II provides a description of racial anxiety, how it is experienced by both whites and people of color, and its behavioral consequences.

- Racial anxiety is discomfort about the experience and potential consequences of interracial interaction.

- People of color can be anxious that they will be the target of discrimination and hostile or distant treatment.

- Whites can be anxious that they will be assumed to be racist and, therefore, will be met with distrust or hostility.

People experiencing racial anxiety often engage in less eye contact, have shorter interactions, and generally seem – and feel – awkward. Not surprisingly, if two people are both anxious that an interaction will be negative, it often is. So racial anxiety can result in a negative feedback loop in which each party’s fears appear to be confirmed by the behavior of the other.

PART III

Part III describes the science underlying stereotype threat, which occurs when a person is concerned that she will confirm a negative stereotype about her group.

- Stereotype threat can affect anyone, depending on the prevailing stereotypes in a given context.

- Stereotype threat has been most discussed in the context of academic achievement among students of color, and among girls in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields.

- Whites can suffer stereotype threat when concerned that they may be perceived as racist.

When people are aware of a negative stereotype about their group in a domain in which they are identified, their attention is split between the activity at hand and concerns about being seen stereotypically.

- Research finds that concern about negative stereotypes can trigger physiological changes in the body and the brain, such as:

- An increased cardiovascular profile of threat and activation of brain regions used in emotion regulation

- Cognitive reactions (especially a vigilant self-monitoring of performance)

- Affective responses (especially the suppression of self-doubts)

- Stereotype threat diverts cognitive resources that could otherwise be used to maximize task performance.

PART IV

Part IV focuses on the role of racial dynamics in education and health care. Implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat have effects in virtually every important area of our lives. In the report, we illustrate the interrelated implications of the three phenomena in the domains of education and health care. Education and health care are of critical importance for obvious reasons – and a fair amount of research has highlighted the role race plays in unequal outcomes in both domains. The research to date includes the findings highlighted below.

Racial Dynamics in Education

- Discipline and suspension disparities were not based upon more severely problematic behavior by black or Latino youth; the greatest racial disparities were in responses to subjective behaviors such as “disrespect” or “loitering.”

- Conventional measures of academic performance underestimated the ability of members of stereotyped groups by 0.17 standard deviations or 62 points on the SAT. The size of this gap is significant and highly likely to be an underestimation.

- Teachers may give students of color too little critical feedback.

Racial Dynamics in Health Care

- Physicians were 40% less likely to refer African Americans for cardiac catheterization than whites; the lowest referral rates were for African American women.

- Doctors’ levels of bias largely mirrored those of the general population, with medical doctors strongly preferring whites over blacks. Doctors in some fields, such as pediatrics, showed less biased behavioral responses to racial difference.

- Physicians engaged with patients of color may be less likely to be empathic, to elicit sufficient information, and to encourage patients to participate in medical decision-making.

- African American patients have a greater level of distrust toward white counselors in clinical settings, which has serious consequences for mental health care, as well as physical health care.

PART V

Part V describes critical interventions that institutions ought to adopt and individuals ought to engage in to respond effectively to the racial dynamics that lead to the harms to targeted groups described above.

“Debiasing” and Preventing Effects of Implicit Bias

The research on reducing implicit bias or “debiasing” is fairly new, however, researchers have conducted recent studies finding some success. Most significantly, Patricia Devine and her colleagues have combined interventions devised by other research and successfully reduced implicit racial bias, as well as increased awareness of personal bias and concern about discrimination. These strategies are listed below.

- Stereotype replacement: Recognizing that a response is based on stereotypes, labeling the response as stereotypic, and reflecting on why the response occurred creates a process to consider how the biased response could be avoided in the future and replaces it with an unbiased response.

- Counter-stereotypic imaging: Imagining counter-stereotypic others in detail makes positive exemplars salient and accessible when challenging a stereotype’s validity.

- Individuation: Obtaining specific information about group members prevents stereotypic inferences.

- Perspective taking: Imagining oneself to be a member of a stereotyped group increases psychological closeness to the stereotyped group, which ameliorates automatic group-based evaluations.

- Increasing opportunities for contact: Increased contact between groups can reduce implicit bias through a wide variety of mechanisms, including altering their images of the group or by directly improving evaluations of the group.

These data “provide the first evidence that a controlled, randomized intervention can produce enduring reductions in implicit bias.” The findings have been replicated and further studies will be in print in 2015.

Preventing Implicit Bias from Affecting Behavior

To the extent that debiasing is an uphill challenge in light of the tenacity of negative stereotypes and attitudes about race, institutions can also establish practices to prevent these biases from seeping into decision-making. Jerry Kang and a group of researchers developed the following list of interventions that have been found to be constructive:

- Doubt objectivity: Presuming oneself to be objective actually tends to increase the role of implicit bias; teaching people about non-conscious thought processes will lead people to be skeptical of their own objectivity and better able to guard against biased evaluations.

- Increase motivation to be fair: Internal motivations to be fair, rather than fear of external judgments, tends to decrease biased actions.

- Improve conditions of decision-making: Implicit biases are a function of automaticity (what Daniel Kahneman refers to as “thinking fast”). “Thinking slow” by engaging in mindful, deliberate processing prevents our implicit biases from kicking in and determining our behaviors.

- Count: Implicitly biased behavior is best detected by using data to determine whether patterns of behavior are leading to racially disparate outcomes. Once one is aware that decisions or behavior are having disparate outcomes, it is then possible to consider whether the outcomes are linked to bias.

Interventions to Reduce Racial Anxiety

The mechanisms to reduce racial anxiety are related to the reduction of implicit bias – but are not identical. In our view, combining interventions that target both implicit bias and racial anxiety will be vastly more successful than either in isolation.

- Direct intergroup contact: Direct interaction between members of different racial and ethnic groups can alleviate intergroup anxiety, reduce bias, and promote more positive intergroup attitudes and expectations for future contact.

- Indirect forms of intergroup contact: When people observe positive interactions between members of their own group and another group (vicarious contact) or become aware that members of their group have friends in another group (extended contact), they report lower bias and anxiety, and more positive intergroup attitudes.

Stereotype Threat Interventions

Most of these interventions were developed in the context of the threat experienced by people of color and women linked to stereotypes of academic capacity and performance, but they may also be translatable to whites who fear confirming the stereotype that they are racist.

- Social belonging intervention: Providing students with survey results showing that upper-year students of all races felt out of place when they began but that the feeling abated over time has the effect of protecting students of color from assuming that they do not belong on campus due to their race and helping them develop resilience in the face of adversity.

- Wise criticism: Giving feedback that communicates both high expectations and a confidence that an individual can meet those expectations minimizes uncertainty about whether criticism is a result of racial bias or favor (attributional ambiguity). If the feedback is merely critical, it may be the product of bias; if feedback is merely positive, it may be the product of racial condescension.

- Behavioral scripts: Setting set forth clear norms of behavior and terms of discussion can reduce racial anxiety and prevent stereotype threat from being triggered.

- Growth mindset: Teaching people that abilities, including the ability to be racially sensitive, are learnable/incremental, rather than fixed has been useful in the stereotype threat context because it can prevent any particular performance from serving as “stereotype confirming evidence.”

- Value-affirmation: Encouraging students to recall their values and reasons for engaging in a task helps students maintain or increase their resilience in the face of threat.

- Remove triggers of stereotype threat on standardized tests: Removing questions about race or gender before a test, and moving them to after a test, has been shown to decrease threat and increase test scores for members of stereotyped groups.

Interventions in Context

The fundamental premise of this report is that institutions seeking to alter racially disparate outcomes must be aware of the array of psychological phenomena that may be contributing to those outcomes. We seek to contribute to that work by summarizing important research on implicit bias that employs strategies of debiasing and preventing bias from affecting behavior. We also seek to encourage institutions to look beyond implicit bias alone, and recognize that racial anxiety and stereotype threat are also often obstacles to racially equal outcomes. We recommend that institutions work with social scientists to evaluate and determine where in the institution’s operations race may be coming into play.

CONCLUSION

The conclusion describes the conditions required for transformative change. Social science described in this report helps people understand why interracial dynamics can be so complicated and challenging despite our best intentions. The interventions suggested by the research can be of value to institutions and individuals seeking to align their behavior with their ideals. Yet for lasting change to occur, the broader culture, and ultimately our opportunity structures also need to change for our society to meet its aspirations of fairness and equal opportunity regardless of race and ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

During the late summer of 2014, as this report was being finalized, Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, were both killed by police officers under circumstances in which race seemed to drive behavior. On August 7, 2014, the second-degree murder verdict was announced against Theodore Wafer, who killed the unarmed Renisha McBride when she sought help at his home after a car accident in 2013. During the trial, Wafer testified that he grabbed his 2-gauge shotgun because he feared for his life. He said he “just reacted” (Bosman, 2014) when he shot her in the face through the door, causing her immediate death. While we cannot know with certainty whether Wafer would have had the same reaction had McBride been white, it seems unlikely. Few are of the view that Eric Garner’s and Michael Brown’s fates would have been the same had they been white. These tragedies do not occur in isolation. They are accompanied by daily instances in which racial or ethnic difference come into play. And yet most Americans espouse values of racial fairness.

Recent advances in neuroscience, social psychology, and other “mind sciences” have provided insight into otherwise confounding contradictions between our stated values and behaviors and outcomes. Advocates and “race talkers” (media pundits who focus on race) have been particularly interested in social psychological research focusing on “implicit bias” – the automatic association of stereotypes or attitudes with particular social groups (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013; Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004; Kirwan Institute, 2013).

Understanding implicit bias can help explain why a black criminal defendant charged with the same crime as a white defendant may receive a more draconian sentence (Mustard, 2001), or why a resume from someone named Emily will receive more callbacks than an otherwise identical resume from someone named Lakeisha (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004; Rooth, 2010). Implicit bias can also help explain why the number of tragic deaths linked to race keeps growing.

The dangers posed by and prevalence of implicit biases – coupled with the growing body of research supporting the link between biases and behaviors (Devine, 1989; Kang & Lane, 2010) – have led institutions such as judges’ associations, police departments, law firms, corporations, school districts, and city governments to begin to engage in efforts to address the effects of implicit bias. This work confirms that people of color whose experiences of the world make abundantly clear that “race matters” are not simply oversensitive, while also explaining how whites who consider themselves non-racist may be sincere, even if their behavior sometimes suggests otherwise. Each of the authors has been working with such institutions to devise training programs and address the racial dynamics that are undermining fairness and equal treatment.

This is not meant to suggest that racialized outcomes are only a result of individual actions; cumulative racial advantages for whites as a group have been embedded into society’s structures and institutions (powell, 2012). As Grant-Thomas & powell (2014) argue: “a society marked by highly interdependent opportunity structures and large inter-institutional resource disparities will likely be very unequal with respect to the outcomes governed by those institutions and opportunity structures.” Today’s structural conditions are a result of racial advantages and disadvantages accumulated during times of overt white supremacy, and these dynamics have proved “very durable indeed” (Grant-Thomas & powell, 2014).

However, there are two key reasons why structural racism cannot be successfully challenged without an understanding of how race operates psychologically. First, public policy choices are often affected by implicit bias or other racialized phenomena that operate implicitly (powell & Godsil, 2014). As a result, the changes in policy necessary to address institutional structures are dependent upon successfully addressing implicit biases that can affect political choices. Second, institutional operations invariably involve human behavior and interaction; any policies to address racial inequities in schools, work places, police departments, court houses, government offices, and the like will only be successful if the people implementing the policy changes comply with them (Grant-Thomas & powell, 2014). Although implicit phenomena have the potential to impede successful institutional change, implicit racial bias is not the only psychological phenomenon that blocks society from achieving racial equality. We risk being myopic if we focus only on people’s cognitive processing. Our experiences, motivations, and emotions are also integral to how we navigate racial interactions (Tropp & Mallett, 2011).

Research suggests that some forms of anti-bias education may have detrimental effects if they increase bias awareness without also providing skills for managing anxiety.

Not surprisingly, then, implicit bias cannot explain all racial dynamics. Racial anxiety and stereotype threat also create obstacles for institutions and individuals seeking to adhere to antiracist practices (Tropp & Molina, 2012; Steele & Aronson, 1995; Goff et al., 2008).

Racial anxiety refers to discomfort about the experience and potential consequences of interracial interactions (Stephan & Stephan, 1985).1 People of color may experience racial anxiety that they will be the target of discrimination and hostile or distant treatment. White people tend to experience anxiety that they will be assumed to be racist and will be met with distrust or hostility (Devine & Vasquez, 1998). Whites experiencing racial anxiety can seem awkward and maintain less eye contact with people of color, and ultimately, these interactions tend to be shorter than those without anxiety (Shelton & Richeson, 2006). If two people are both anxious that an interaction will be negative, it often is. So racial anxiety can result in a negative feedback loop in which each party’s fears seem to be confirmed by the behavior of the other.

Stereotype threat refers to the pressure that people feel when they fear that their performance may confirm a negative stereotype about their group (Steele & Aronson, 1995). This pressure is experienced as a distraction that interferes with intellectual functioning. Although stereotype threat can affect anyone, it has been most discussed in the context of academic achievement among students of color, and among girls in STEM fields (Steele, 2010). Less commonly explored is the idea that whites can suffer stereotype threat when concerned that they may be perceived as racist (Goff et al., 2008). In the former context, the threat prevents students from performing as well as they ought, and so they themselves suffer the consequences of this phenomenon. Stereotype threat among whites, by contrast, often causes behavior that harms others – usually the very people they are worried about. Concern about being perceived as racist explains, for example, why some white teachers, professors, and supervisors give less critical feedback to black students and employees than to white ones (Harber et al., 2012) and why white peer advisors may fail to warn a black student but will warn a white or Asian student that a certain course load is unmanageable (Crosby & Monin, 2007).

In other words, cognitive depletion or interference caused by stereotype threat can affect how one’s own capacity, such as the ability to achieve academically, will be judged; this causes first-party harm to the individual, whose performance suffers. However, as is explored in more detail below, stereotype threat about how one’s character will be judged (e.g., being labeled a racist), can cause third-party harms when experienced by an individual in a position of power.

Social science research in this context is valuable because it contributes to our understanding of otherwise confounding racial dynamics in the face of egalitarian values. Crucially, social scientists have also begun to identify interventions that have shown success in preventing the behavioral effects of implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat. This report summarizes the cutting-edge research explaining these phenomena and identifies best practices for institutions, policy makers, and individuals working toward racial equality.

PART I: THE OPER ATION OF IMPLICIT BIAS

Most whites, believing themselves to be non-racist, reasonably conclude that race has diminished in significance – and high-profile examples such as the race of the President confirm this belief. Yet people of color – particularly black people – often have a significantly different perception of the degree to which race affects their lives and opportunities. In a 2013 Gallup poll, 68% of African Americans and 40% of Hispanics stated that the American justice system is biased against black people, compared to only 25% of non-Hispanic whites (Newport, 2014). The mind sciences provide an explanation for both sets of beliefs – white people’s belief that they and most other whites are not “racist” and the belief of African Americans and Latinos that America continues to be biased.

A. AUTOMATIC PROCESSING OF STIMULI INTO CATEGORIES

It is well-recognized that human beings process the enormous amount of stimuli we encounter by ordering the environment through the use of categories (“schemas”) and automatic associations between concepts that share related characteristics (Tajfel & Forgas, 1981). This automatic ordering is a critical human function that makes processing of information more efficient and guides our reactions and behaviors in relation to our environment. Classes of stimuli are not static; we construct new schema as our environment changes. In the 21st century, for example, the category of “cell phone” allows us to respond appropriately to a small metal object emitting some sort of noise – a category which did not exist throughout most of the 20th century.

Just as categories can determine how we respond to objects, the construction of categories for people is the foundation for everyday social interaction. For example, kindergarten teachers automatically categorize people in their classroom on the first day of school into student and family member. The association of characteristics with the categories of “child” and “adult” makes this task instantaneous. Children quickly learn to respond automatically with polite attention to the person categorized as their teacher and to be extra quiet when the person called “Principal” walks into the classroom. The categories “student,” “teacher,” and “principal” perform important social functions that allow the school to function smoothly.

We often also associate an attitude – an evaluative valence – with a category (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). For example, people may generally share the association of certain attributes with the category “teacher” – those who teach in schools – but hold quite different valences (warm feelings or cold feelings) toward teachers.

The automatic association of characteristics and valences with social categories performs an important social function, allowing us to respond appropriately to people fitting the definitional categories. However, social categories can be laden with definitional characteristics that are not neutral. For example, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the category “Irish” was associated with images of drunkenness and criminality – “stereotypes” (generalizations) which were far from neutral or definitional (Ignatiev, 2008). Although these stereotypes no longer have a hold on the culture, stereotypes about other racial and ethnic groups have proved more intractable. Stereotypes associating blacks, and to some degree Latinos, with violence, criminality, and poverty have been and continue to be constant in the media, even as these stereotypes are outwardly rejected (Bobo, 2001; Eberhardt et al., 2004; Dixon, 2009).

Stereotypes associating blacks, and to some degree Latinos, with violence, criminality, and poverty continue to be constant in the media, even as these stereotypes are outwardly rejected.

In other words, relatively few people in U.S. society today believe consciously – i.e., explicitly – that all people who are black and Latino are poor and prone to criminality. Many more people, however, hold automatic associations of those tendencies when they see someone who they identify as black or Latino. Regular exposure to such representations in the media can result in inaccurate and hostile associations toward people who fit into those social categories.

Although many social categories are subject to stereotypes and negative attitudes, in this report we focus on implicit associations with currently stigmatized racial and ethnic groups. In this context, implicit racial biases can be understood to include automatic stereotypes and attitudes that result from repeated exposures to cultural stereotypes of different racial groups that pervade society (Richardson & Goff, 2012).

B. MEASURES OF BIAS

Social scientists have developed an increasingly sophisticated array of mechanisms for identifying and measuring the presence of automatic stereotypes and attitudes we consciously deny, or which fall beyond our conscious awarness.

The Implicit Association Test (IAT), developed by Anthony Greenwald and housed at Harvard’s ProjectImplicit.org, is one well-known measure (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). The IAT measures whether there is a time difference between a person’s ability to associate a particular social category with concepts that reflect either stereotypes or attitudes. For example, the attitude-based race IAT measures the latency between a person’s association of black or white faces with “good” words (positive valence) and “bad” words (negative valence). While considered a reliable measure, the IAT is not akin to a DNA test – it is not a precise and entirely stable measure of bias in any single individual; rather it reveals patterns and tendencies among large groups of people (Kang et al., 2010) and therefore can explain statistically significant differences in decision-making and treatment linked to race and other salient factors (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013).

Scientists are also beginning to use physiological tools to measure implicit responses to race, including functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) (Phelps et al., 2000), patterns of cardiovascular responses (Blascovich et al., 2001); facial electromyography (EMG) (Vanman et al., 2004), and cortisol responses (Page-Gould et al., 2008). These physiological tools provide additional insight into our reactions to race and ethnicity. For example, neuroscientists are using fMRI analysis to detect both the presence of implicit racial bias and the brain activity that occurs when a person is trying to control bias (Gilbert et al., 2012; Ochsner & Gross, 2008). The study by Gilbert et al. (2012) shows, for example, that two distinct aspects of racial bias – implicit stereotyping and implicit evaluation or attitude – are mediated by different brain mechanisms.

Scientists are also beginning to use physiological tools to measure implicit responses to race.

C. IN-GROUP PREFERENCE VS. OUT-GROUP ANIMUS

Implicit bias is a result of the automatic, unconscious association of attributes with different groups, but at an explicit or implicit level, bias can also manifest as a result of comparatively positive preferences for one group over another. Social scientists refer to this phenomenon as “in-group” bias or preference (Brewer, 1999; Tropp & Molina, 2012). In-group bias is more likely to be explicit than is animus, but it can often be implicit as well. Whites who hold explicit in-group preference will rarely interpret their feelings as “racist” if they do not involve active animus against people of other races. Yet, when biases and preferences become translated into behavior, the result is the same: members of one racial group benefit relative to members of another.

Although we tend to think of racial discrimination primarily as treating a person or a group worse, treating a favored racial group better results in the same outcome (Reskin, 2000). For example, studies have shown that whites generally will not overtly rate blacks negatively – they will simply rate similarly situated whites more positively (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). Obviously, to the extent these biased evaluations and preferences have tangible implications in real-world contexts, they matter.

Contrary to popular belief, in-group bias is not static, and not all “groups” feel or show the same degree of in-group bias. It depends upon the dynamics of a particular culture. For example, whites in our society tend to show a greater degree of in-group bias than blacks or members of other races (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). In-group bias is also most prevalent when in-group members perceive a threat to resources that benefit the in-group, (Riek et al., 2006) or norms that legitimize the status quo (Tropp & Molina, 2012; Sidanius et al., 1996).

It is also important to note that not everyone who fits within any particular group holds biases or preferences favoring that group. We all have many identity groups to which we belong, and the salience of these identity groups differs across individuals and within varying contexts. For example, a white American may feel more “in-group” preference toward a black American than toward other white people when both are in France.

When people experience in-group bias, they tend to be more “comfortable with, have more trust in, hold more positive views of, and feel more obligated to members of their own group” (Reskin, 2000). In the context of in-group bias linked to race, researchers have found that people may try to avoid out-group members – an avoidance which often leads to distortions in perception and bias in evaluation of in-group and out-group members which results in discrimination (Reskin, 2000; see also Brewer & Brown, 1998).

Additionally, in-group bias leads people to feel more empathy toward members of their own group (Chiao et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009). This finding has been documented using fMRI studies measuring the level of activity in the amygdala (an area of the brain that mediates pain) and the perception of the pain experienced by others. In the 2009 Xu et al. study, researchers showed participants video clips of faces contorted to reflect the experience of pain. When participants viewed pictures of in-group members experiencing pain, the fMRI documented high activity levels in the relevant brain region, but the activity level dropped when in-group members viewed clips of out-group members experiencing pain (Xu et al., 2009).

A similar study used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to measure corticospinal activity level in participants who were shown short video clips of a needle entering into the hand of either a white or black target (Avenanti et al., 2010). As with the 2009 fMRI study, researchers here found that region-specific brain activity levels are higher when a white participant views the clip of a white target experiencing pain than when a white participant sees a clip of a black target experiencing pain.

Researchers have concluded that the increased empathy that many whites show for other whites is culturally learned rather than inborn.

The neural reaction is not inherent or universal. Because it differs depending up on the relative status of and relationships between different racial groups, researchers have concluded that this neurological response is culturally learned rather than inborn (Avenanti et al., 2010). The authors conclude that this research “uncover[s] neural mechanisms of an empathic bias toward racial in-group members” which serve as a basis for understanding social behaviors and that “lead some people to provide more help to racial in-group than out-group members” (Avenanti et al., 2010).

The combination of implicit negative associations with minority groups and in-group preferences among whites appears to result from of our country’s hardened racial categories and pervasive racialized associations. These interrelated phenomena have effects in important life domains, including criminal justice, employment, education, and health treatment. It cannot always be determined whether a particular disparate effect is a result of a negative view toward one racial group or an in-group preference toward the dominant group, but the combined results of the two are profound.

D. BEHAVIORS LINKED TO IMPLICIT BIAS

The effects of implicit bias are not limited to the unconscious mind. Researchers have amassed powerful evidence that implicit bias (both negative bias toward people of color and positive bias toward whites) does not simply remain in the unconscious, but translates into a wide range of behaviors that have significant effects. In other words, those with negative implicit racial attitudes or who automatically stereotype display behavior consistent with those attitudes (McConnell & Leibold, 2001).

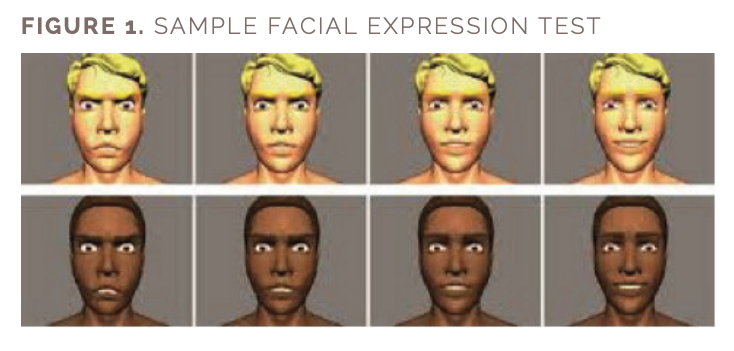

This behavior ranges from perceiving facial expressions differently to offering job callbacks at different rates to seeing guns more quickly in relation to some racial groups relative to others. Specifically, in studies of facial expressions, whites with stronger implicit racial bias perceive black faces as angrier than whites with weaker levels of bias; similarly, those with stronger implicit bias are apt to consider an expression happy or neutral if displayed by a white person, but neutral or angry if displayed by a black person (Hugenberg & Bodenhausen, 2003).

And in a multitude of experiments in which participants are directed to “shoot” video images of people with a gun as quickly and accurately as possible, those with higher implicit bias levels shoot black targets holding guns faster and more accurately than white targets holding guns (Payne et al., 2005; Payne, 2001; Correll et al., 2002; Correll et al., 2007). Implicit bias manifests itself in real-world decisions as well as laboratory experiments (Greenwald et al., 2009). Field studies demonstrate that black and Latino job applicants are significantly less likely to receive callbacks than are equally qualified white applicants (Pager et al., 2009). Particularly disturbing was the finding that black defendants who have stereotypically black features serve up to eight months longer and that such defendants are more likely to be sentenced to death in cases involving white victims (Eberhardt et al., 2006).

The adverse effects of implicit bias also carry beyond black-white relations. Indeed, implicit bias research has shown broad implications of such bias against a wide range of groups. For example, implicit negative associations toward Asian Americans has been linked to less positive assessments of the competence of Asian Americans as litigators (Kang et al., 2010), resistance to hiring Asian American candidates for national security jobs, and rejecting progressive immigration policies if proposed by Asian Americans (Yogeeswaran & Dasgupta, 2010).

Researchers have realized for decades that negative and positive attitudes are often reflected in our nonverbal behaviors (Word et al., 1974). Most of us know intuitively that nonverbal behaviors – including degree of interpersonal distance, eye contact, and other behaviors – determine whether we read someone as friendly and open or as hostile and closed (Dovidio et al., 2002), and when what people say appears to contradict how they say it, we are unlikely to believe the words we hear. For example, we may be inclined to question the veracity of someone who says, “I am so happy to see you,” when this is uttered with no eye contact and pursed lips. As such, research finds that implicit attitudes predict people’s nonverbal behaviors, while explicit attitudes predict the content of peoples’ words; moreover, when there are discrepancies between them, we may be more likely to attune to others in relation to their nonverbal behaviors, where implicit biases are more likely to be revealed (Dovidio et al., 2002). In research studies mimicking job interviews, Word et al. (1974) found that whites showed more positive nonverbal behaviors toward other whites than toward black candidates, such as sitting closer to them; at the same time, whites spent 25% less time with black candidates and had higher rates of speech errors with them than with white candidates (Word et al., 1974).

Implicit bias often receives attention when tragedies strike, but it is replicated in everyday micro-behaviors demonstrating that race affects social perception – such as the clutched purse when a black man enters the elevator, the assumption that a black lawyer works in the mail room or as a secretary, the query about whether a Latino or Asian American speaks English, or the question “Where are you really from?” asked of fellow citizens from different racial and ethnic groups. People can consciously reject negative stereotypes or attitudes in relation to different groups, but those negative stereotypes or attitudes can still be triggered automatically or “implicitly.”

Addressing implicit bias is clearly a crucial step. Yet researchers warn that those who make an effort to reduce bias and inhibit the automatic activation of negative attitudes and stereotypes must be mindful of the potential for “rebound effects” (Dovidio et al., 2008) that trigger racial anxiety or stereotype threat.

PART II: RACIAL ANXIETY

Racial anxiety can be acute, experienced as physiological threat (Blascovich et al., 2001; Page-Gould et al., 2008) and cognitive depletion (Richeson & Shelton, 2003; Richeson et al., 2003; Richeson & Shelton, 2007) in anticipation of and following an interracial interaction. When people experience the physical symptoms of anxiety during a cross-racial interaction, they often distance themselves, are less apt to share eye contact, and use a less friendly and engaging verbal tone – behaviors which can obviously undermine an interaction (Dovidio et al., 2002).

Racial anxiety matters on multiple levels, and its effects can spill over into virtually every important life domain. Members of both racial minority and majority groups may experience racial anxiety and its concomitant discomfort in cross-race interactions; moreover, members of racial minority groups may be subject to adverse effects of the racial anxiety among members of the dominant group with whom they interact. Given that white people continue to be overrepresented in positions of greater power, their anxiety can have significant consequences for members of other racial and ethnic groups. What this means is, for example, a black patient may suffer the effects of her own experience of interracial anxiety with a white doctor, but may also suffer the effects of the doctor’s anxiety. As a result, it is in everyone’s interest to identify and address the effects of racial anxiety.

A. INTERGROUP ANXIETY AS AN EVERYDAY OBSTACLE

Beginning in the 1980s with work by Walter and Cookie Stephan (Stephan & Stephan, 1984, 1985), social scientists have developed a robust literature addressing the fact that people often feel more anxious when interacting with “out-group” members than with “in-group” members. In a review of the literature, Tropp and Page-Gould (2014) explain that this observation has been replicated with a “host of convergent measures of anxiety, ranging from self-reported anxiety (Britt et al., 1996; Stephan & Stephan, 1985) to anxious behaviors (Dovidio et al., 2006; Dovidio et al., 2002) and physiological stress responses” (Amodio, 2009; Mendes et al., 2007; Page-Gould et al., 2008, Tropp & Page-Gould, 2014). Although the studies are not limited to race as the source of stigma (Blascovich et al., 2001), we are particularly interested in the application of this research to racial dynamics because race – and specifically relations between whites and African Americans – has represented such a salient divide in the United States.

Who Experiences Racial Anxiety

Racial anxiety, like implicit bias, is common, but not experienced by everyone. Some people may be more susceptible to experiencing racial anxiety, and it may have different underlying causes for the people who do experience it. For some, bias or prejudice is the source of the racial anxiety (Page-Gould et al., 2008; Stephan & Stephan, 1985). However, for others, it is the concern that the interracial interaction will not go well – rather than bias – that causes the racial anxiety (Tropp & Page-Gould, 2014; Trawalter et al., 2009). As we will discuss below in the interventions section, it is important to know the source of the anxiety to know how best to ameliorate it.

Other research emphasizes the role of both actual and perceived psychological threat as fundamental components of intergroup anxiety (Stephan & Stephan, 2000; Tropp & Page-Gould, 2014). This model when applied to race can be applicable both to whites as the dominant group and people of color as stigmatized groups. Among many whites, racial or ethnic prejudice predicts anxiety. These whites are more likely to perceive interactions with people of color as demanding (Dovidio et al., 2002; Trawalter et al., 2009), and they are worried about how they will be seen during the interactions (Amodio, 2009; Vorauer, 2006; Vorauer & Kumhyr, 2001; Vorauer et al., 2000). In a set of intriguing studies, prejudiced whites were actually likely to spend more cognitive resources trying to make the interaction go smoothly (Richeson & Shelton, 2003; Richeson et al., 2003; Richeson & Shelton, 2007). People with little prior contact with out-group members have also been found to react viscerally and more negatively to cross-group interactions (Blascovich et al., 2001; Mendes et al., 2002).

On average, people of color have more contact with whites and, as a result, may feel a greater sense of efficacy about interacting with whites (Doerr et al., 2011). Nonetheless, they may still experience anxiety when they expect to be rejected on the basis of race or ethnicity (Mendoza-Denton et al., 2006; Page-Gould et al., 2008; Pinel, 1999; Stephan & Stephan, 1989; Tropp, 2003).

In light of the importance of the prevailing social norm of egalitarianism, many whites truly fear being perceived as racist.

Some may find it surprising that whites may experience “racial anxiety” given the continued dominance of whites generally – but in light of the importance of the prevailing social norm of egalitarianism, many whites truly fear being perceived as racist. Racial anxiety is more likely when whites are externally motivated not to appear racist than whites who are internally motivated by egalitarianism (Plant et al., 2008). In other words, we can be focused on not being racist – or focused on whether other people see us as racist. The latter can translate into the phenomenon of stereotype threat described in the next part of the report.

B. ANXIETY FEEDBACK LOOPS IN INTERACTION

People who are experiencing racial anxiety exhibit some of the same behaviors as those who have implicit bias – even though, as discussed above, the source may be different. Researchers have found that people who feel anxious during interactions with people of other races or ethnicities are less likely to seek out or engage in subsequent interactions (Butz & Plant, 2011; Dovidio et al., 2006; Plant & Butz, 2006; Plant & Devine, 2003; Tropp, 2003). A negative experience with someone of another race or ethnicity can trigger a negative feedback loop where the experience of racial anxiety predicts fewer and lower-quality interactions with other racial and ethnic groups in the future (Paolini et al., 2006; Tropp & Page-Gould, 2014). This negative feedback loop creates a barrier to effective interracial contact because people with limited contact experience are more likely to have awkward or negative interactions (Blascovich et al., 2001) and so will be more motivated to avoid future contact.

Conversely, prior positive interracial contact can have a wide range of positive consequences, including improved interracial attitudes, more successful interracial interactions, and following from these, more positive inclinations toward future interracial interactions (Levin et al., 2003; Swart et al., 2011; Tropp, 2003). Importantly, prior positive experiences with people of other races or ethnicities can reduce the effects of later negative experience (Paolini et al., 2014). These positive interactions also translate into greater resilience when a later interracial experience is stressful (Page-Gould et al., 2010).

As a result of “pluralistic ignorance,” whites and people of color are apt to behave in ways that confirm the other’s fears.

The positive effects of interracial or ethnic contacts may not occur immediately, particularly among strangers after a single brief meeting (Page-Gould et al., 2008; Tropp & Page-Gould, 2014). Rather, these effects generally develop over time (Page-Gould et al., 2008). In other words, people become more comfortable and experience less racial anxiety if they have repeated interactions with members of other groups rather than meeting just once. Indeed, even people with high levels of implicit bias who showed physiological signs of stress during a first interracial interaction showed fewer signs of stress in a second meeting, and by the third meeting showed no more stress than they would have with a person of the same race (Page-Gould et al., 2008). Stress levels during interracial experiences are important because they make that particular interaction more successful – but also because the lower stress level of one interracial interaction has been shown to make later interracial experiences more positive (Page-Gould et al., 2010).

C. DISTINGUISHING EFFECTS OF RACIAL ANXIETY AND BIAS

When we experience racial anxiety, we may not recognize it – and we are even less likely to recognize that the person with whom we are interacting may be experiencing it as well. Thus, as a result of “pluralistic ignorance,” whites and people of color are apt to behave in ways that confirm the other’s fears – failing to initiate contact through open body language, eye contact, and other non-verbal signals of welcoming interaction (Shelton & Richeson, 2005). The absence of this kind of body language makes both people appear unfriendly or unwelcoming. In sum, racial anxiety begets more racial anxiety.

Pluralistic ignorance occurs when “people observe others behaving similarly to themselves but believe that the same behaviors reflect different feelings and beliefs” (Shelton & Richeson, 2005). Shelton and Richeson have concluded that both whites and blacks report interest in contact with one another, but both believe the other group will have little interest in interaction with them (Shelton & Richeson, 2005). The studies confirmed that both attributed their own lack of action to engage in interracial contact to be a fear of rejection, but presume that inaction by the member of the other racial group reflects lack of interest.

These tendencies are particularly acute in the context of race. Because of continued patterns of segregation, people are particularly likely to generalize from a single act committed by an individual member of a different race to the larger racial group to which that individual belongs. For instance, a white person who does not feel welcome to sit at a table with a black person may generalize this experience into a broad conclusion that black people as a group are not interested in interacting with whites. Similarly, a black person who observed the white person walking by the open seat at the table will conclude that whites as a group are not interested in interacting with black people.

Such interactional dynamics may seem trivial when compared to structural challenges, but they are crucially important in our day-to-day experiences, including interactions with teachers, employers, and health care providers.

PART III: STEREOTYPE THREAT

Stereotype threat can be triggered whenever a person is concerned that their actions or performance may confirm a negative stereotype about their group. The term is most often used in the context of stereotypes about abilities or capacities – verbal acuity, math or science proficiency, or athletic skills – but stereotypes can also involve assumptions about character traits about a particular group: the Irish as garrulous and prone to drink too much; Asian Americans as studious and anti-social; whites as racist. This section will discuss the implications of both types of stereotype threat and the behavioral effects when a person is subject to stereotype threat.

A. ABILITY-RELEVANT STEREOTYPE THREAT

Stereotype threat is most often examined as the fear of confirming a stereotype that one’s group is less able than other groups to perform a valued activity. Most stereotype threat studies in the United States have focused on the effects of stereotype threat in academic settings for at-risk groups – including women in the STEM fields and black and Latino students more generally (Spencer et al., 1999; Walton et al., 2013). Stereotype threat for black and Latino students has been identified as “the norm in academic environments” (Walton et al., 2013). A recent meta-analysis concluded that stereotype threat accounts for a substantial proportion of racial achievement gaps (Walton & Spencer, 2009).

In early studies of stereotype threat in the context of race, Steele and Aronson (1995) administered a test to black and white Stanford students, which was composed mainly of questions from the Graduate Record Examination (GRE). The students were instructed to complete the test under one of two different conditions. In the “threat” condition, students were told that their performance on the test would be diagnostic of their intellectual ability, an instruction that activated a negative stereotype of intellectual inferiority; in the “no threat” condition, the test was characterized as a mere problem-solving task that was not intended to evaluate their intellectual ability. Under the “threat” condition, black students performed substantially worse than white students, but under the “no threat” condition, black students’ performance improved significantly, virtually eliminating the racial gap between black and white students (Steele & Aronson, 1995).

Steele and Aronson concluded that when the test was represented as evaluative of ability, which is how most tests are represented and understood, black students became anxious that a poor performance could seem to confirm the negative stereotype of intellectual inferiority, and in turn, this anxiety disrupted their test performance. But when the test was presented in the “no threat” condition, the instructions made negative intellectual stereotypes less relevant, and black students’ performance improved dramatically.

This basic research finding has been replicated in hundreds of studies (Brown & Day, 2006). When people are aware of a negative stereotype about their group, their attention is split between the test at hand and worries about being seen stereotypically. Anxiety about confirming negative stereotypes can trigger physiological changes in the body and the brain (especially an increased cardiovascular profile of threat and activation of brain regions used in emotion regulation), cognitive reactions (especially a vigilant self-monitoring of performance), and affective responses (especially the suppression of self-doubts). These effects all divert cognitive resources that could otherwise be used to maximize task performance (Schmader & Johns, 2003).

B. CHARACTER-RELEVANT STEREOTYPE THREAT

Not all stereotypes involve the presumption that a group is less able to perform well on a certain task. In addition to being seen as competent, most of us also care about whether we are seen as adhering to prevailing morals or norms. Under prevailing moral norms, to be racist is to be immoral, and many white people are concerned that they may be presumed to be prejudiced or racist (Plant & Devine, 1998; Zurwink et al., 1996; Goff et al., 2008). An important question is whether the concern that one may be seen as racist leads to an internal desire to avoid racist behavior or to a motivation to avoid being perceived as racist.

Researchers sought to test the effect of this concern – and how it translates into behavior. Building on earlier research showing that in mock interviews whites tended to sit farther away from black than from white job interviewees (Word et al., 1974), Goff et al. (2008) engaged in a series of experiments to investigate whether whites’ fear of being stereotyped as racially prejudiced by a black conversation partner might lead them to physically distance themselves from their partner. The researchers hypothesized that the possibility of a racially tense conversation would trigger stereotype threat in white participants, which in turn would lead them to physically distance themselves from the black partners. The study confirmed that participants who were assigned to talk about racial profiling with two black men distanced themselves more from their partners than if they were talking to other whites or about less charged topics (Goff et al., 2008). The study also showed that white participants sat farther away from black partners than from white ones when they were expected to discuss their own views about racial profiling but did not do so when openly assigned an opinion (where they would not be perceived as discussing their own views). Importantly, the white participants’ levels of implicit bias did not predict whether they would sit farther away from the black conversation partners; rather, their levels of concern about being seen as racist predicted their actions (Goff et al., 2008).

The researchers also sought to determine whether the white participants were conscious of the stereotype threat when they had been informed that they would be discussing racial profiling with a black conversation partner. They found that 27% of the participants openly showed stereotype threat-relevant thoughts. Examples of stereotype threat-relevant thought listings included statements such as the following (Goff et al., 2008):

“I feel awkward knowing that I, a white person, will be talking to a black man about racial profiling”; “I hope it doesn’t affect my conversation on the subject that the other person is of a different race, though I don’t imagine it would”; “My first thought when I saw ‘racial profiling’ as a topic, and my partner was of a different ethnicity was that I might want to be cognizant of this and be somewhat careful in my remarks”; and “Oh shit, this guy is black!”

As discussed above, distancing behavior – like other nonverbal behavior – has an effect on those who experience it. In the work by Word et al. (1974), researchers found that people who are subject to distancing and other nonverbal behaviors tend to reciprocate with similar behavior. Indeed, these researchers found that the black candidates in the distancing condition responded in kind and, as a result, were rated as significantly less adequate for the job, as well as less calm and composed (Word et al., 1974).

PART IV: EXAMPLES OF EFFECTS OF IMPLICIT BIAS , RACIAL ANXIETY, AND STEREOTYPE THREAT

Implicit bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat have effects in virtually every important area of life. In this part, we focus on the interrelated implications of these phenomena in two areas of critical importance: education and health care. Clearly not all of the disparities in education and health outcomes are attributable to individual actions that may be impacted by implicit bias, racial anxiety, or stereotype threat; there are broader structural issues at play as well. But as the political struggle to address structural inequities continues, institutions can and should adopt practices that will address the social dynamics and behavior that contribute to racial inequities.

A. RACE AND EDUCATION

In the educational context, racial disparities in discipline and achievement receive considerable attention in the national dialogue. While the causes are undoubtedly complex, the specter of the white teacher who fails to recognize the academic potential of young people of color and views them as disruptive or inattentive has been empirically established (Dee, 2005). Despite the prevalence of this image, it is unlikely that white teachers enter teaching with the explicit goal of harming students of color. The phenomena addressed in this report – implicit racial bias, racial anxiety, and stereotype threat – help explain how well-meaning and consciously egalitarian teachers may inadvertently contribute to some of the disparities we observe.

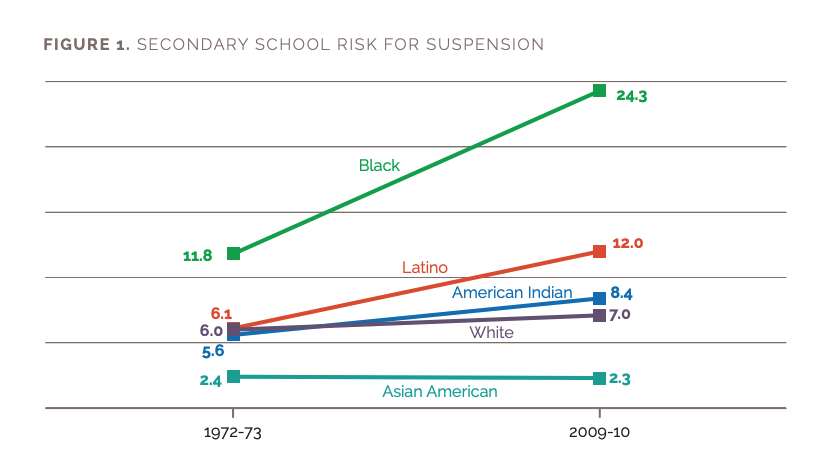

1. The Data: Race in Suspension and Discipline A recent report by the U.C.L.A. Civil Rights Project shows an extraordinary increase in student suspensions from the 1970s to the present, but also illustrates that the most dramatic increases were among black and Latino students (Losen & Martinez, 2013). Suspension rates for white students increased by only 1.1% (from 6 to 7.1%), while the rates for black and Latino students more than doubled. In the 1970s, hardly the halcyon days of race relations, black student suspension rates where 11.8 %, and Latino students’ rates were 6.1%. In 2009-2010, black students’ rates were 24.3%, and Latino students’ rates were 12%. The intersection between race and gender also demonstrates dramatic differences, with the percent of African American girls suspended 14% higher than that of white girls.

Some may argue that implicit bias is not at issue and that the numbers simply reflect differences in behavior. However, the data fail to support this conclusion. School districts and schools have wildly varying suspension rates. Chicago has the highest number of “hot spot” schools (84) in which 25% or more of the student body was suspended in a given year. Los Angeles has both the highest number of lowsuspending schools (81) in which fewer than 10% of any subgroup within a school are suspended in a given year, but also 54 “hot spot” schools.

The research undermines any assumption that suspension rates reflect different levels of suspension-worthy behavior by black and Latino youth. Skiba et al. (2011) found that discipline and suspension disparities were not based upon more severely problematic behavior by black or Latino youth such as bringing weapons to school or acting aggressively toward other students, but instead that the greatest racial disparities were in responses to subjective behaviors such as “disrespect or loitering.” They found that black and Latino students may be less likely to be given detention or other moderate consequences, but that black students have almost four times the odds, and Latino students twice the odds, “of being suspended or expelled for a minor infraction at the elementary school level” (Skiba et al., 2011). While this over-representation was somewhat less pronounced in the middle school years, Skiba et al. (2011) still found that black students “are significantly more likely than white students to be suspended or expelled for disruption, moderate infractions, and tardy/truancy, while Latino students were more likely to be suspended or expelled in Grade 6–9 schools for all infractions except use/possession.”

2. Implicit Bias and Education

Gregory et al. (2010) posit that implicit bias may play a role in disproportionate discipline, though they acknowledge that no one has yet studied teachers’ implicit biases directly. Vavrus & Cole (2002) conducted an ethnographic study of urban schools and found that officer referrals which ultimately led to suspensions were a result of students’ “violation of implicit interactional codes,” in which a student was seen as calling into question established classroom practices or the teacher’s authority. This research, while not conclusive, suggests that implicit racial biases may well be affecting disciplinary decisions.

Few teachers are likely to admit to others (or even to know themselves) that they hold students to different standards or have varying expectations based on race or ethnicity. To date, researchers have not yet published outcomes of studies of the direct link between teachers’ race- or ethnicity-based implicit bias and their assessments of student capacity or merit. As described below, studies have addressed the issue of whether teachers and others who work with students assess students differently based upon race and ethnicity.

Research outside of education confirms our fears that race may directly affect determinations of merit. For example, in a recent study by a consulting firm working with law firms, 60 partners were given an identical memorandum written by “Thomas Meyer,” identified as a summer associate from New York University Law School (a top 10 school), that contained 22 different errors, 7 of which were minor spelling/grammar errors, 6 of which were substantive technical writing errors, 5 of which were errors in fact, and 4 of which were errors in analysis (Nextions, 2014). Half of the partners were led to believe that Meyer was white (Caucasian) and the other half that Meyer was African American. The results quoted below from the study’s report are telling:

- An average of 2.9/7.0 spelling/grammar errors were found in “Caucasian” Thomas Meyer’s memo in comparison to 5.8/7.0 spelling/grammar errors found in “African American” Thomas Meyer’s memo.

- An average of 4.1/6.0 technical writing errors were found in “Caucasian” Thomas Meyer’s memo in comparison to 4.9/6.0 technical writing errors found in “African American” Thomas Meyer’s memo.

- An average of 3.2/5.0 errors in facts were found in “Caucasian” Thomas Meyer’s memo in comparison to 3.9/5.0 errors in facts were found in “African American” Thomas Meyer’s memo.

“Caucasian” Meyer

- “generally good writer but needs to work on…”

- “has potential”

- “good analytical skills”

“African American” Meyer

- “needs lots of work”

- “can’t believe he went to NYU”

- “average at best”

This appears to be a case of “confirmation bias,” in which reviewers saw what they expected to see based upon stereotypes and then drew conclusions that confirmed those stereotypes (Nextions, 2014). It is notable that the most significant disjuncture in errors between reviews of “Caucasian” Meyer and “African American” Meyer were simple spelling errors, yet these few more spelling errors called into question “African American” Meyer’s suitability as a law student at NYU.

The “Meyer” study seems to be a case of “confirmation bias,” in which reviewers saw what they expected to see based upon stereotypes and then drew conclusions that confirmed those stereotypes.

Broader data sets tell a somewhat more complicated story. In a meta-analysis of studies assessing whether teacher expectations differ according to race or ethnicity, Tenenbaum & Ruck (2007) found that teachers hold a small but statistically significant higher level of expectations for Asian American students than for white students, and a small but statistically significant higher level of expectations for white students as compared to black and Latino students. They noted, however, that teachers who were teaching simulated lessons were more likely to hold lower expectations of black students than teachers who viewed a videotape or listened to an audio tape – and, notably, teachers who read vignettes rated black students more highly than white students (Tenenbaum & Ruck, 2007).

These results were not uniform, however, and conclusions differed depending upon the location of the study. Studies in which the authors did not specify the region showed larger effect sizes than those focused on the South, Northeast and Southwest, with studies in the Midwest showing virtually no difference, and studies in the West showing slightly more positive expectations for black students than white students (Tenenbaum & Ruck, 2007).

The variability of the studies suggests that when seeking to apply research to specific institutions it will be important to avoid making assumptions about how bias applies in every context. However, the Tenenbaum and Ruck meta-analysis, as well as a host of individual studies, confirms that general negative stereotypes about the academic capacities of students of color may affect teacher expectations, which can in turn create a warped lens through which teachers judge student performance.