The Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society and the Economic Policy Institute jointly filed an amicus brief (friend of the court) of 62 housing scholars in the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. the Inclusive Communities Project, a critical case before the Supreme Court that will determine the scope of the nation’s landmark Fair Housing Act.

The Inclusive Communities Project claims the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs (TDHCA) administers the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program in a manner that perpetuates and magnifies segregation in the Dallas metropolitan region.

The LIHTC is the nation’s largest program for creating affordable housing today—in 2014 alone, the program allocated over $900 million to 46 states. As an indirect subsidy, states have wide latitude to implement selection criteria for selecting and approving developments that receive the federal credit. The vast majority of projects approved under TDHCA’s selection criteria have been in segregated, racially isolated neighborhoods, while denying applications in white areas, thereby limiting the economic and educational opportunities of low-income housing residents. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Texas Housing and Community Affairs, but the state appealed to the Supreme Court.

The case presents the question to the nation’s highest court whether the “disparate impact” standard can be used to enforce the Fair Housing Act. Disparate impact recognizes that policies often have discriminatory results regardless of intent. The Civil Rights Act of 1968, which remains the U.S.’s most vital mechanism for promoting equal housing opportunity and disestablishing patterns of racial segregation, prohibits housing discrimination by charges all governmental units with the duty to “affirmatively further fair housing.”

"Although our nation has made considerable progress towards racial equality, residential segregation remains fundamentally intact five decades after passage of the Fair Housing Act, limiting opportunities for many families for a better life."

- Stephen Menendian

The Haas Institute/EPI amicus brief, filed in support of the Inclusive Communities Project, explains why disparate impact claims are necessary to redress the legacy of government sponsored segregation. Using a series of maps (including those displayed below), the brief describes the current patterns of segregation in the Dallas metropolitan region over five decades, illustrating how the LIHTC’s program has a discriminatory impact on non-white housing residents. The brief reminds the Court that historically governmental policies at the federal, state and local levels created the segregated conditions of our metropolitan region. The brief reiterates that seemingly race-neutral government decisions and private housing choices both perpetuate and exacerbate those patterns of segregation.

The disparate impact standard, the brief argues, remains essential to address the ongoing legacy of these discriminatory policies. The disparate impact standard has been affirmed in eleven federal court of appeals cases.

“Although our nation has made considerable progress towards racial equality, residential segregation remains fundamentally intact five decades after passage of the Fair Housing Act, limiting opportunities for many families for a better life,” notes Stephen Menendian, assistant director of the Haas Institute said. Menendian, one of the brief’s authors, said the scholars who signed the brief believe that disparate impact claims are necessary to ensure that governmental entities’ land use or housing decisions account for residential patterns brought into existence through historical public policies and private discrimination, instead of inadvertently continuing these patterns or making them worse. “Our maps show how segregation patterns tend to replicate themselves over time,” he added.

Sixty-one social scientists, housing historians, demographers, and other researchers familiar with segregation and its effects, signed in support of the brief, including Christopher Edley, Jr, faculty director of UC Berkeley’s Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy and Richard Rothstein, senior fellow at the Warren Institute and research associate at the Economic Policy Institute. Other distinguished scholars of the amicus group include Elizabeth Anderson, John Brittain, Nancy Denton, James Kushner, Ira Katznelson, Myron Orfield, Jr., and Gregory Squires.

Mr. Rothstein noted, “Housing developers, as well as state housing authorities, have long sought a case like this to appeal to the Supreme Court, hoping to end the use of disparate impact as a standard that could prevent them from building subsidized apartments for low-income minority families in already segregated neighborhoods. If the Court bans the disparate impact standard, it will annihilate one of the few tools available to pursue housing integration. This amicus brief shows why the disparate impact standard is necessary to implement the requirement of the Fair Housing Act that government programs affirmatively further integrated housing.”

The Haas/EPI brief was one of over a dozen briefs filed to the Court in this case, including briefs in support of the Inclusive Communities Project by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Fair Housing Alliance, the City of San Francisco, and many others. A full list of briefs and responses can be found at the SCOTUS blog on this case. Arguments are expected to begin in late January.

For more information about the brief, contact: Stephen Menendian at smenendian@berkeley.edu

For media inquires, contact Rachelle Galloway-Popotas at galloway.popotas@berkeley.edu or 510-642-3325.

Mapping Persistent Housing Segregation Dallas

This map, which was presented in the amicus brief, shows the distribution of LIHTC- subsidized developments in Dallas County as of 2010. Only six out of 162 LIHTC projects were sited in majority white neighborhoods. Seventy-two percent of projects approved in the Dallas Metropolitan area are sited in predominantly non-white census tracts. Map by Samir Gambhir.

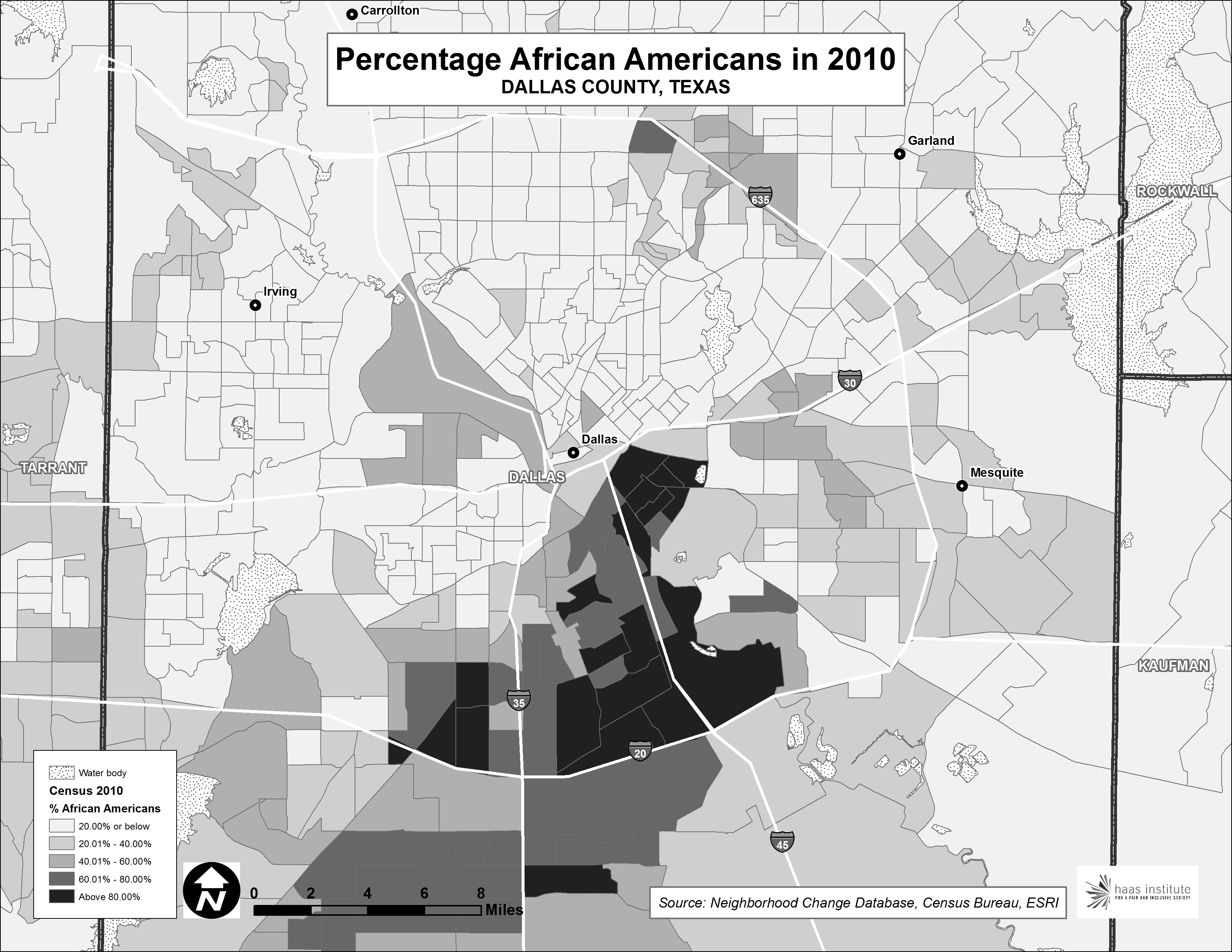

African American Segregation 1970-2010

This series of maps shows segregation patterns in the Dallas area from 1970 to 2010. The more darkly shared areas represents census tracts with larger percentages of African American families.

PERCENTAGE OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN 1970

Nationwide segregation, as measured by the dissimilarity index, peaked in 1970. This map of Dallas shows stark patterns of racial segregation and isolation for African American families in Dallas.

PERCENTAGE OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN 1980

In 1980, a few African American families expanded within south Dallas and moved into inner ring suburbs within the region. The vast majority still lived in the city.

PERCENTAGE OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN 1990

In 1990, more African American families moved into south Dallas neighborhoods, yet the majority of north Dallas census tracts remained predominantly white.

PERCENTAGE OF AFRICAN AMERICANS IN 2010

While the majority of African American families continue to live south of Dallas’ main highway, the percentage in many south Dallas areas has decreased. Many Black families have moved to inner ring suburbs adjacent to longtime segregated areas. The predominantly white neighborhoods of north Dallas have remained segregation.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at UC Berkeley is a research institute bringing together scholars, community stakeholders, policymakers, and communicators to identify and challenge the barriers to an inclusive, just, and sustainable society in order to create transformative change.

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank created in 1986 to include the needs of low- and middle-income workers in economic policy discussions. EPI believes every working person deserves a good job with fair pay, affordable health care, and retirement security. To achieve this goal, EPI conducts research and analysis on the economic status of working America. EPI proposes public policies that protect and improve the economic conditions of low- and middle-income workers and assesses policies with respect to how they affect those workers.