The Haas Institute's Disability Studies and Diversity & Health Disparities clusters hosted a March 6 film screening to revisit the 1997 sci-fi movie Gattaca and discuss its impact on the public imagination and how we think about the ethical and social questions around human reproductive and gene-editing technologies.

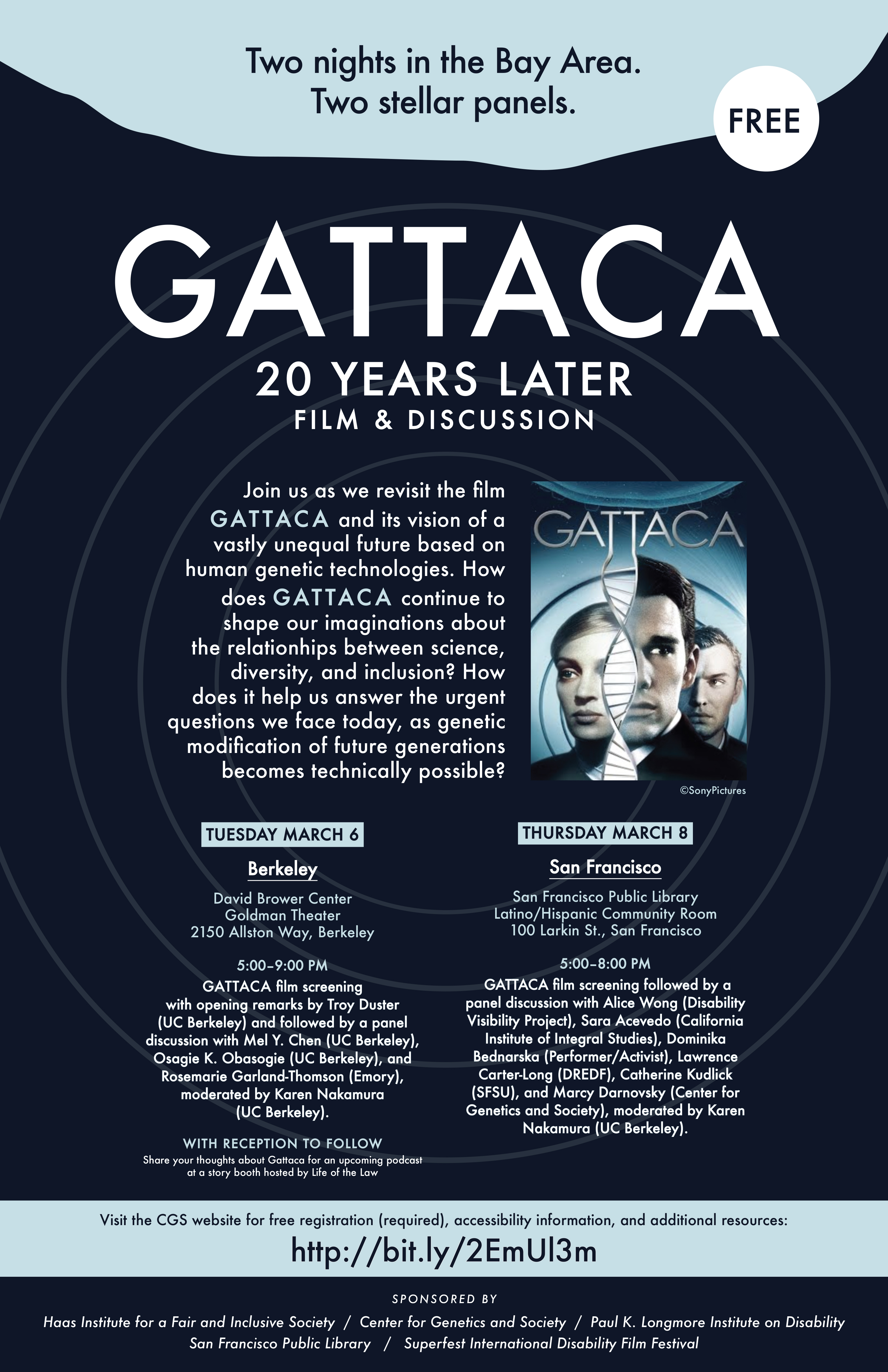

The event was organized by Bioethics Professor Osagie Obasogie and Professor Karen Nakamura of Cultural Anthropology, and took place at the Brower Center in Berkeley, and was followed by a panel discussion on the moral themes of the movie.

During the event, Nakamura raised questions about our perceptions of belonging in relation to people with disabilities. In the movie, the main character, Vincent, played by Ethan Hawke, was born of natural conception in a society dominated and organized by genetically engineered elites. Because Vincent was born without genetic manipulation, he is deemed an “invalid” and unable to participate in society. The character who required a wheelchair after an accident, Eugene, could no longer operate in the Gattacan society only designed for humans in so called perfect physical and mental condition. Thus Eugene’s life becomes a symbolic sacrifice of his "valid" DNA, in the form of daily donations of blood and urine to “validate” Vincent’s entry into a job that allowed him to pursue his dream of traveling to space. Both Vincent and Eugene are excluded and regulated to exist at the margins of society until they form an alliance against the oppressive forces of exclusion. Nakamura encouraged the panelists and audience to reflect on our society’s obsession with categorizing people and organizing society according to these categories.

Obasogie also challenged the audience to reflect on the complex history of eugenics--the process of trying to produce a population with certain genetic traits by controlled breeding--and the lethal perversion of this scientific ideology when it’s used to socialize people into believing that they must fit a specific profile.

Further, Obasogie lifted up the humanistic qualities displayed in Gattaca like love, parental decision making, perseverance over presumed obstacles, and alliance building. The event was not absent the humanist perspective that is too often left out of debates on the principles of scientific advancement. It was there to remind us of the importance and power of human connection.

Answering questions about what is natural versus what is unnatural requires all the expertise we can muster. The event was equipped with reading materials that gave a basic introduction to gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPER-Cas9, to help people without technical or biological backgrounds in genetics understand things more clearly.

Obasogie’s article “Revisiting Gattaca in the Era of Trump” raises important questions about social and political acceptance of technological developments used to “engineer better humans” within the social contexts of racial hatred, xenophobia and increasing inequalities across all aspects of society. Further, disability rights activists critique the persistence of dominant narratives promoting physical and mental perfection which inherently deny the value of difference represented in disability.

Further Obasogie’s recently published edited volume Beyond Bioethics: Toward a New Biopolitics seeks to take on “the social and political challenges posed by new human biotechnologies such as assisted reproduction, human genetic modification, and DNA forensics” with a keen awareness of the function of structural exclusion on the basis of race, gender, class, disability, privacy, and notions of democracy.

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, an English Professor at Emory University, disability justice and culture thought leader, and bioethicist who served as a panelist at the event, reminded the audience not to get caught by the doom and gloom or a false nostalgia for the “good old days.” She spoke about exciting new opportunities for people living with genetics diseases and other disabilities to get involved in informing stakeholders on best practices in meeting the specific needs of people most impacted. The Minority Coalition for Precision Medicine (MCPM) founded by sickle patient advocates Shakir Cannon and Michael Friend, is one such organization working to bridge the gap between medical science researchers and minority groups. In particular, Garland-Thomson’s work as a disability justice advocate calls for people with disabilities to develop disability cultural competence. Garland-Thomson’s blog advises persons with disabilities to cultivate authority and dignity by getting involved with supportive organizations and communities. Her point here is that as more people know their rights and access resources, informed persons experiencing systematic and social inequities can collectively advocate for the societal shifts required to achieve inclusion.

Still, we have to contend with the harsh realities in the function of structural racism and its systemic locking of specific groups out of opportunities. Biotech companies leading in regulatory approvals to research and to treat genetic diseases must be held accountable to create equity and inclusion in their work that can serve and advance all people. Garland-Thomson raised a very important question about who determines how information about the use of CRISPER-Cas9 in pro-creative / pre-genetic counseling is distributed. We are in a very critical time that requires deep reflection on questions on the notions of regulations. Currently, regulations are driven by super powerful tech companies who use market-based logic to make decisions about the fate of humanity.